Summary

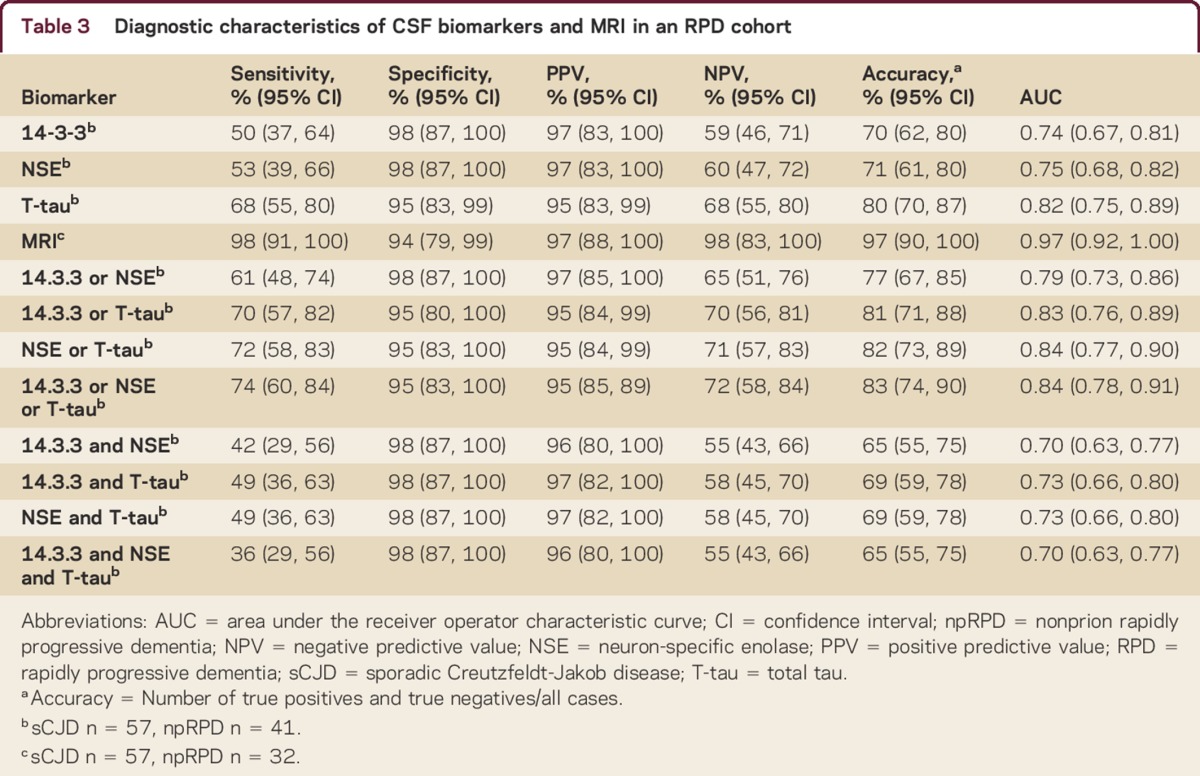

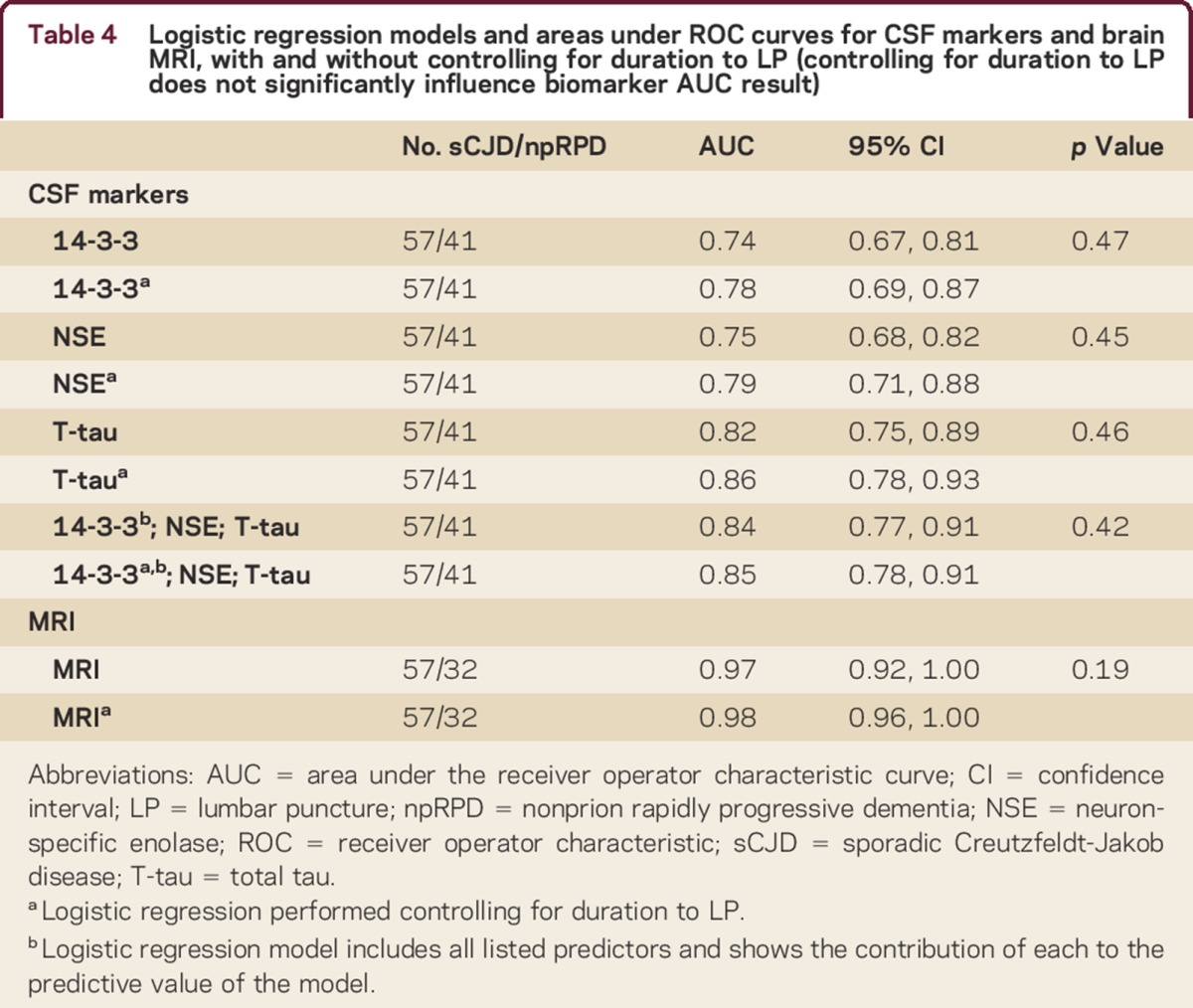

We assessed the diagnostic utility of 3 CSF biomarkers—14-3-3 protein, total tau (T-tau), and neuron-specific enolase (NSE)—from the same lumbar puncture to distinguish between participants with neuropathologically confirmed sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD, n = 57) and controls with nonprion rapidly progressive dementia (npRPD, n = 41). Measures of diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value, as well as logistic regression and area under the receiver operator curve (AUC), were used to assess the ability of these CSF biomarkers, alone or concomitantly, to predict diagnosis. In a subcohort with available MRI (sCJD n = 57, npRPD = 32), we compared visual assessment of diffusion-weighted imaging MRI sequences to these CSF biomarkers. MRI was the best predictor, with an AUC of 0.97 (confidence interval [CI] 0.92–1.00) and a diagnostic accuracy of 97% (CI 90%–100%). Of the CSF biomarkers, T-tau had a higher diagnostic accuracy (79.6%) than 14-3-3 (70.4%, CI for difference 8.7%, 9.7%; p = 0.048) or NSE (71.4%, CI for difference 7.6%, 8.7%; p = 0.03).

CSF levels of 14-3-3 protein were first reported to be useful diagnostic markers for sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD) in 1996.1 Since then, numerous publications have addressed its utility in the differential diagnosis of sCJD, with variable findings. In the literature, the sensitivity of 14-3-3 has most commonly been reported between 85% and 95%,2–8 although it has been reported to range from 53% to 97%.1,9,10 Its specificity has been reported to range from 40% to 100%.2,4,7,8,11–13 Other CSF protein markers, such as neuron-specific enolase (NSE) and total tau (T-tau), have been used to diagnose CJD; whether these markers are better than 14-3-3 has been a matter of debate. 14-3-3, for example, has been found to have higher accuracy than T-tau in some,2 but not all, studies.5,13,14 The ratio relationship between T-tau and phosphorylated tau (T-tau/P-tau) has also increasingly been shown to be a useful indicator of disease diagnosis in sCJD, with sensitivities ranging from 75% to 94%3,9,15,16 and specificities ranging from 94% to 97%.3,9,15,16

Because of the generally poor sensitivity and specificity of CSF 14-3-3 for sCJD in our rapidly progressive dementia (RPD) cohort,10,17,18 and because different CSF markers often yield discordant results in the same patient, we compared the diagnostic utility of CSF 14-3-3, NSE, and T-tau in participants who had all 3 biomarkers tested at the same time. We also compared them with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) MRI, which has been shown to be highly sensitive19,20 and specifice1,e2 for sCJD diagnosis, even early in the course.e2 For those patients who also had P-tau assessed, we performed a secondary analysis focusing on the diagnostic utility of T-tau/P-tau.

METHODS

Standard protocol approvals, registration, and patient consents

This study, and the use of human participants, was approved by our institution's Internal Review Board.

Participants

The participants included in this analysis were referred to the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Memory and Aging Center from March 1, 2005, to April 9, 2012. We queried our database for participants who had 14-3-3, NSE, and T-tau assessed from the same lumbar puncture (LP). In participants with multiple LPs, only the first available sample assessing these 3 CSF biomarkers was used. We restricted sCJD to pathology-proven cases, yielding 57 participants. Fifty-five of 57 participants with sCJD had prion protein gene (PRNP) analysis, including codon 129 polymorphism (National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center [NPDPSC], Cleveland, OH); all had no mutation. The 2 remaining participants had no known family history of prion disease or neuropsychiatric illness.

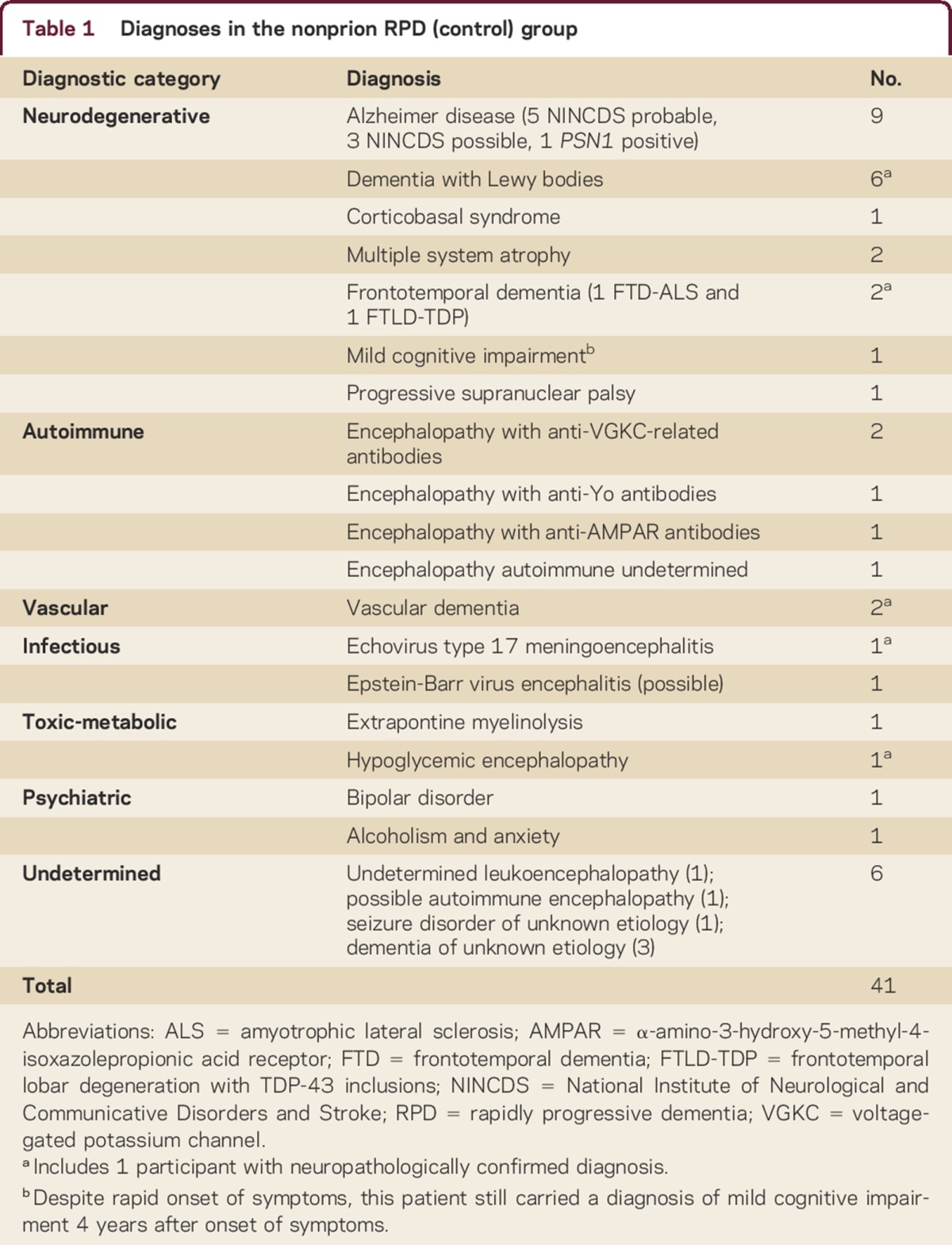

The nonprion RPD (npRPD) cohort was obtained from participants in whom CJD was considered at some point in their disease course; most had a rapidly progressive decline. npRPD participants were included if they had (1) a clearly defined serologic or pathologic diagnosis, (2) a significant clinical improvement, or (3) a total disease duration longer than 3 yearse3,e4 (supplemental data at Neurology.org/cp), yielding 41 participants. Their clinical diagnoses (5 neuropathologically proven) are detailed in table 1. Thirty (73%) of 41 controls had PRNP sequencing (NPDPSC, Cleveland) and were negative for mutations; the remaining 11 had no reported family history of prion disease or similar disorder.

Table 1.

Diagnoses in the nonprion RPD (control) group

CSF analysis

CSF 14-3-3 protein testing by Western blot was performed at the NPDPSC, and reported as positive, negative, or ambiguous. For analysis, negative and ambiguous results were grouped as negative, a methodology employed by other studies2,4 and supported by our own analysis on our larger 14-3-3 CSF dataset (supplemental data). NSE testing was performed by Mayo Medical Laboratories (Rochester, MN) in 46 sCJD (81%) and 37 (90%) npRPD cases, Quest Diagnostics (San Juan Capistrano, CA) in 10 sCJD (18%) and 4 npRPD (10%) cases, and ARUP Laboratories (Salt Lake City, UT) (1 sCJD case). T-tau testing was performed at the NPDPSC in 17 sCJD (30%) and 12 npRPD (29%) cases and Athena Diagnostics (Worcester, MA) in 40 sCJD (70%) and 29 npRPD (71%) cases (supplemental data). P-tau testing was performed in 26 npRPD (63%) and 38 (67%) sCJD cases, all by Athena Diagnostics (supplemental data).

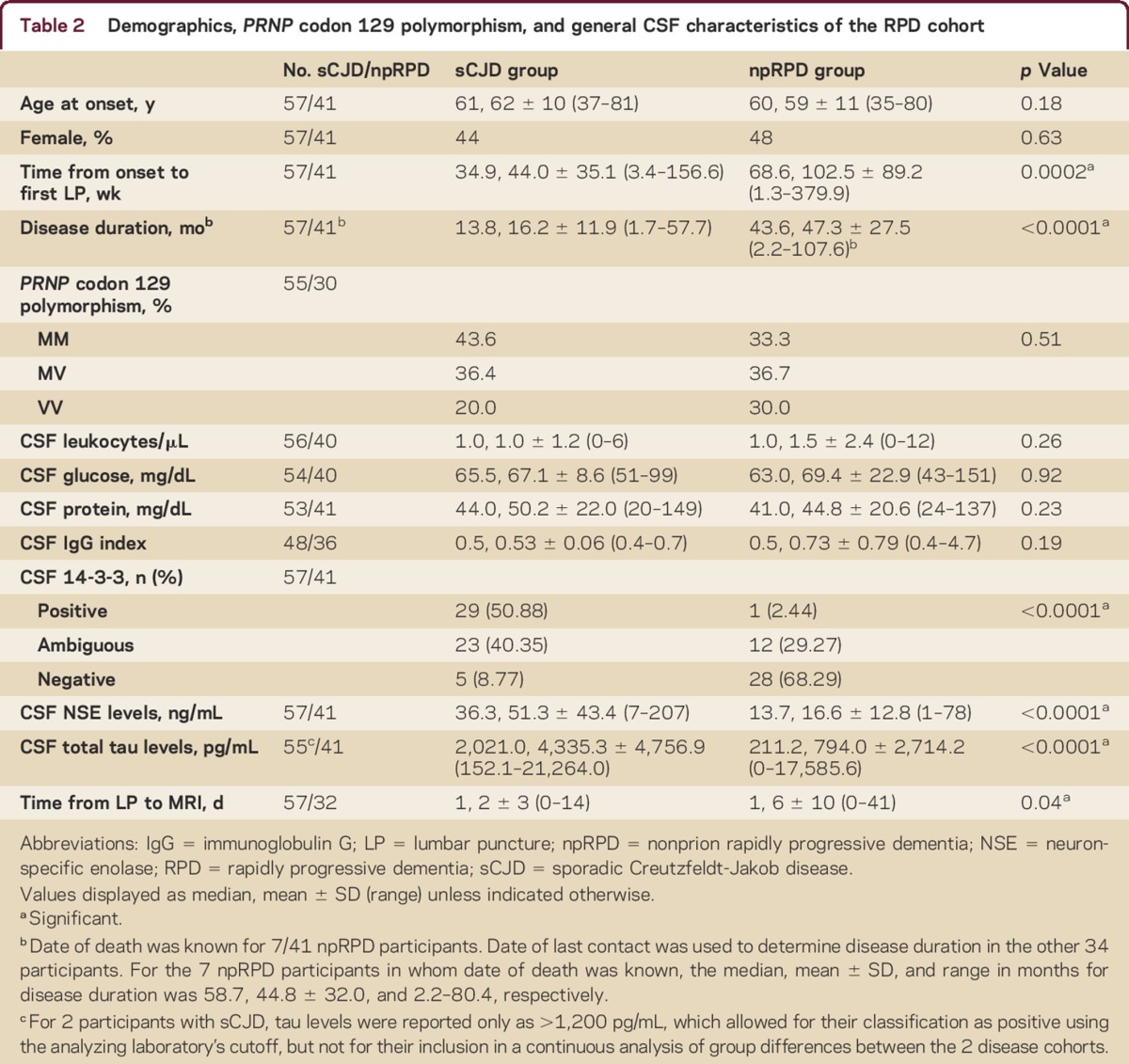

Neuroimaging

MRI scans were obtained on 1.5T or 3T scanners. MRIs classified as definitely or probably CJD based on our previously described criteriae1 were considered positive (supplemental data). MRIs were read by neurologists or neuroradiologists in the CJD/RPD research group at UCSF blinded to clinical data, except patient's age and sex. Duration of time from LP to MRI is shown in table 2. Only MRIs performed within ±45 days of the LP and deemed of adequate quality were used. In 95% of the sCJD and 78% of the npRPD cases, MRI was performed within 1 week of the LP (table 2).

Table 2.

Demographics, PRNP codon 129 polymorphism, and general CSF characteristics of the RPD cohort

As NSE and T-tau were assayed in different laboratories, and MRIs performed on different scanners, we used standard meta-analysis techniquese5 to assess heterogeneity across sites. We did not find that the variability of results was greater than might be expected by chance (supplemental data).

Neuropathology

Neuropathologic assessment was done through the NPDPSC or UCSF in 55 sCJD cases. Two sCJD autopsies were performed at other medical centers (supplemental data).

Statistical analysis

We compared demographic and clinical data using χ2, t tests, or Mann-Whitney tests, depending on data type and normality. The diagnostic utility of each isolated biomarker, as well as multiple biomarkers in combination, was quantified using estimates of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value, accuracy, and area under receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (AUC) accompanied by 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Their predictive ability was compared based on DeLong's test for 2 ROC curves accompanied by permutation.e6 CIs are inferred based on 1,000 bootstrap samples.e7

Because length of time from symptom onset to LP has been shown to have an effect on some CSF biomarkers,4,10,13 we controlled for duration from symptom onset to time of LP (duration to LP) in ancillary analyses. In most cases, date of symptom onset was based on extensive interviews with the patient, his or her family, or his or her friends,e8 as well as outside medical records. In these analyses, the diagnostic utility of logistic regression (LR) models in which all 3 of the CSF biomarkers were included was examined based on a score derived from coefficients representing weights of CSF biomarkers in predicting diagnosis. Statistical analyses were performed in SAS (v 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) or the R package for statistical computing (R Development Core Team).

RESULTS

The 2 cohorts did not differ significantly in sex, age at disease onset, or general CSF findings (table 2). sCJD participants had shorter duration to LP and disease duration, and a longer interval between LP and MRI (table 2). The distribution of sCJD molecular subtypes is shown in table e-3.

MRI analyses

Concomitant MRI within ±45 days of the LP was available in all 57 sCJD cases and in 78% (32/41) of npRPD participants. LR analyzing MRI individually showed it to be the most robust predictor, with an AUC of 0.97 (CI 0.92–1.00) and diagnostic accuracy of 97% (CI 90%–100%), significantly higher than any of the CSF determinants considered, or any permutation thereof (table 3). We did not find that duration to LP significantly influenced the predictive ability of this measure (table 4). Fifteen participants with sCJD (26%; p < 0.001) had a negative 14-3-3, NSE, and T-tau result. In 14/15 of these cases, MRI predicted the correct diagnosis.

Table 3.

Diagnostic characteristics of CSF biomarkers and MRI in an RPD cohort

Table 4.

Logistic regression models and areas under ROC curves for CSF markers and brain MRI, with and without controlling for duration to LP (controlling for duration to LP does not significantly influence biomarker AUC result)

CSF biomarker analyses

The diagnostic accuracy for T-tau in our cohort was 79.6%, higher than the accuracy for 14-3-3 (70.4%, CI for difference between T-tau and 14-3-3 7.6%–8.7%; p = 0.04) or NSE (71.4%, CI for difference between T-tau and NSE 7.6%–8.7%; p = 0.045).

There was discordance among 14-3-3, NSE, and T-tau (one test did not agree with the other two) in 18 (32%) participants with sCJD. When discordant, T-tau was positive (correct) in 15, NSE in 6, and 14-3-3 in 5 observations (supplemental data). Only 1 participant with npRPD, with AMPAR limbic encephalopathy, had discordant results (positive T-tau, negative 14-3-3 and NSE). We performed multiple analyses to determine the optimal combination of the CSF biomarkers in our primary analysis for prediction of sCJD diagnosis (table 3). Although some inclusive combinations, such as a positive NSE or a positive T-tau result being considered as diagnostic for sCJD, yielded slightly higher diagnostic accuracies and AUCs, these were not significantly higher than T-tau alone. Duration to LP did not significantly influence the utility of any of the 3 CSF biomarkers, either individually or concomitantly (table 4). In the subcohort of patients for whom we had available P-tau data, we found that the diagnostic accuracy for T-tau/P-tau was 75% (CI 64%–86%), the sensitivity was 63% (CI 46%–78%), the specificity was 92% (CI 75%–99%), and the AUC was 0.78 (CI 0.68–0.87).

DISCUSSION

This study was designed to directly compare 14-3-3, NSE, and T-tau with each other and with MRI in the diagnosis of sCJD using a control cohort of participants with npRPD initially referred with suspected prion disease. MRI had far better diagnostic utility than any individual CSF biomarker or combination thereof.

One reason 14-3-3, NSE, and T-tau are not as helpful as MRI is that they are nonspecific markers of rapid neuronal injury.7,e9,e10 Other studies have combined different CSF markers for increased accuracy in the diagnosis of sCJD.2,4,5 Although this is a reasonable approach, one of the issues often faced in clinical practice is that those tests might yield conflicting results, so determining which CSF biomarker is the most likely to predict a correct diagnosis is important. In this cohort, 18/57 sCJD (but only 1 npRPD) participants had discordant 14-3-3, NSE, and T-tau results; when there was discordance, T-tau was correct much more commonly than 14-3-3 or NSE. In our statistical analysis, T-tau had greater diagnostic accuracy than 14-3-3 or NSE, and performed statistically as well as any permutation of CSF biomarkers in either inclusive or exclusive scenarios of diagnostic determination. Our findings might be particularly useful when trying to interpret conflicting results, and indicate that prioritizing the T-tau result is advisable. This is not to suggest, however, that NSE, 14-3-3, or other CSF biomarkers should not be tested when sCJD is a possible diagnosis. In the proper statistical framework, they have been shown to be very helpful in refining the differential when prion disease is suspected.e11 Elevated 14-3-3 does not, however, equate with CJD. Although it is interesting to note that T-tau/P-tau had a lower AUC and diagnostic accuracy than T-tau alone, since we did not perform a formal validation comparing this measure to the others tested, we cannot comment on its diagnostic utility in this cohort.

The sensitivities of the CSF biomarkers were lower and the specificities similar or higher in our cohort than has been reported by others.2,4,5,13,14,e12 The reason for this is not entirely clear, but could be due to disparities in sample size or referral biases across centers. As a major referral center for prion disease, our cohort had a high proportion of sCJD cases. Based on our larger RPD cohort consisting of patients who did not have all 3 CSF biomarkers tested from the same LP, we suspect that by including more npRPD cases, the PPV would significantly decrease for CSF biomarkers and not change significantly for MRI. Conversely, many national CJD surveillance centers screen dementia populations using these CSF biomarkers, and referrals are based on positive results. This might result in higher sensitivity and lower specificity.13,e13–e15

The sensitivity of these biomarkers has been reported to be influenced by factors such as age at onset,2,4,9 duration of disease,4,9 timing of LP,2,e16 or molecular subtype (based on PRNP codon 129 polymorphism and prion protein isoform).e17 There is some evidence that serial LPs are more likely to yield positive CSF biomarkers in CJD,4 and that participants with longer disease courses and duration to LP are more likely to have negative biomarkers.9,10,13 The median disease duration in our sCJD cohort was 13.8 months, which is longer than typically reported in the literature.e18 This might in part be explained by the fact that we query patients, their family, and their caregivers extensively regarding first symptoms and often find that the earliest indicators of disease can occur months before the first symptoms reported in the medical records, or initially by the family. We accounted for duration of disease to LP in ancillary analyses, however, and did not find that it significantly influenced the predictive value of any of the LR models for MRI, or CSF biomarkers individually or concomitantly. Our lower CSF biomarker sensitivity also might be explained by our under-representation of classic (MM1/MV1) sCJD cases.4 Our finding that the general CSF profiles between the sCJD and npRPD cohorts were similar is not inconsistent with the literature.e19

Although we found brain MRI to be the best test for the diagnosis of sCJD, it is not perfect and is dependent on a reader familiar with typical CJD findings,e20,e21 and others have reported different results. One recent study found T-tau to have identical diagnostic accuracy to MRI (93%), in part because there was higher T-tau sensitivity (80%) and no false-positive T-tau results.e12 This difference might be due to the small sample size, not all of whom had MRI or T-tau testing.

We had 1 false-negative and 2 false-positive MRIs in our cohort. The false-negative scan was in a patient with the MM2 molecular subtype who also had no positive CSF biomarkers in the sample tested. The 2 false-positive MRIs were in npRPD participants with seizures (one of these epileptic participants, who also had hypoglycemia, had the highest level of T-tau observed in the entire cohort as well as a positive 14-3-3 and a very elevated NSE result). Recent seizures, particularly if prolonged, are a well-described cause of DWI cortical ribboning and can even cause basal ganglia hyperintensity.e22 Therefore, one should be cautious diagnosing sCJD based on a positive DWI MRI in this setting. Once the seizures are controlled, however, these DWI abnormalities should remit within days or weeks.e22,e23

There were some limitations to our study. First, the sample size is relatively small. Replicating our results in a large and independent cohort is necessary. Our distribution of certain sCJD molecular subtypes differed from those reported by other groups, with fewer MM1/MV1 cases.13 Additionally, the CSF biomarker results were obtained from different laboratories, and the MRIs on different scanners, which could potentially influence our results. This, however, reflects general clinical experience in the United States, where diagnostic information is culled from numerous sources. Additionally, we did not find that the variability of results, either between laboratories or between scanners, was greater than that which might be expected by chance. Ideally, however, the same laboratories and reagent kits would have been used for analysis of the various CSF biomarkers, and the same scanner for the acquisition of the MRI data.

One advantage of this study is our inclusion of npRPD participants in whom CJD was considered in the differential diagnosis, even if they were not pathology-proven. Restricting the control cohort to pathology-proven cases would miss many of the participants referred to our center whom were initially suspected of having prion disease, but ultimately were found to have other etiologies and either survived a long time or improved with or without treatment, and better replicates general clinical experience. Despite the stringent inclusion criteria applied to the npRPD cohort, our diagnostic certainty for these participants is not as high as that for the sCJD group.

These data suggest that brain MRI acquisition, including fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, DWI, and apparent diffusion coefficient sequences, should be a mainstay of the assessment of patients with suspected sCJD, particularly in atypical cases or when CSF testing shows conflicting or negative results. In this cohort, T-tau was a better diagnostic measure of sCJD than 14-3-3 or NSE, but much less accurate than MRI. It is important to stress that MRI should always be interpreted within the clinical context, however, and expertise in interpreting CJD MRIs is required. False-positives and false-negatives, although rare, do occur,17,e22 and MRIs in sCJD are often misread by radiologists.e20,e21

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the referring physicians; the US National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center (NPDPSC) for assistance with PRNP genetic analyses, prion typing, and some pathologic analyses; the CJD Foundation; and their patients and their families.

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org/cp

STUDY FUNDING

Supported by NIH, National Institute on Aging K23AG021989, R01-AG031189, P50-AG05142, P50-AG021601, NINDS contract N01-NS-0-2328, NCRR UCSF-CTSI grant number UL1 RR024131, State of California, Alzheimer's Disease Research Center of California (ARCC) grant 01-154-20, and the Michal J. Homer Family Fund.

DISCLOSURES

S.A. Forner and L.T. Takada report no disclosures. B.M. Bettcher receives research support from the NIH/NIA 1 K23 AG042492 and an Alzheimer's Association New Investigator Grant. I.V. Lobach receives grant support from the NIH/NIA. M.C. Tartaglia serves on a DSMB of UCSF Investigator-initiated trial in AD and receives research support from CIHR 325708 and 133355 Alzheimer's Society of Canada. C. Torres-Chae, A. Haman, J. Thai, and P. Vitali report no disclosures. J. Neuhaus serves as Statistical Editor for JAMA Internal Medicine and as an Associate Editor for Statistics in Medicine; receives publishing royalties for Generalized, Linear and Mixed Models (John Wiley, 2008); and receives grant support from the NIH/NIA and many grants to UCSF from NIH. A. Bostrom reports no disclosures. B.L. Miller receives grant support from the NIH/NIA; serves as a consultant for TauRx, Allon Therapeutics, and Siemens Medical Solutions; has received a research grant from Novartis; serves as Scientific Advisor for Tau Consortium, Medical Advisor for the John Douglas French Foundation, Director of The Larry Hillblom Foundation, and on the scientific advisory boards for Nat'l Institute for Health Research in Dementia, FasterCures, A Center of the Milken Institute, and Tangled Bank Studios; serves as Editor of Neurocase and on the editorial advisory boards of Cambridge University Press and Guilford Publications, Inc.; and receives publishing royalties for Behavioral Neurology of Dementia (Cambridge, 2009), Handbook of Neurology (Elsevier, 2009), and The Human Frontal Lobes (Guilford, 2008). H.J. Rosen receives grant support from the NIH/NIA and from the Bluefield Foundation. M.D. Geschwind serves on the editorial board of Dementia & Neuropsychologia; receives grant support from the NIH/NIA, the Michael J. Homer Family Fund, the Tau Consortium, and CurePSP; and serves/has served as a consultant for Best Doctors, Guidepoint Global, and Quest Diagnostics (Contract, pending), Lundbeck Inc., MedaCorp, Gerson-Lehman Group, The Council of Advisors, and Neurophage. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hsich G, Kenney K, Gibbs CJ, Lee KH, Harrington MG. The 14-3-3 brain protein in cerebrospinal fluid as a marker for transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. N Engl J Med 1996;335:924–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chohan G, Pennington C, Mackenzie JM, et al. The role of cerebrospinal fluid 14-3-3 and other proteins in the diagnosis of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in the UK: a 10-year review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81:1243–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahl JM, Heegaard NH, Falkenhorst G, et al. The diagnostic efficiency of biomarkers in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease compared to Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2009;30:1834–1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanchez-Juan P, Green A, Ladogana A, et al. CSF tests in the differential diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurology 2006;67:637–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coulthart MB, Jansen GH, Olsen E, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of cerebrospinal fluid protein markers for sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in Canada: a 6-year prospective study. BMC Neurol 2011;11:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins SJ, Sanchez-Juan P, Masters CL, et al. Determinants of diagnostic investigation sensitivities across the clinical spectrum of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain 2006;129:2278–2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stoeck K, Sanchez-Juan P, Gawinecka J, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker supported diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and rapid dementias: a longitudinal multicentre study over 10 years. Brain 2012;135:3051–3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muayqil T, Gronseth G, Camicioli R. Evidence-based guideline: diagnostic accuracy of CSF 14-3-3 protein in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: report of the guideline development subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2012;79:1499–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baldeiras IE, Ribeiro MH, Pacheco P, et al. Diagnostic value of CSF protein profile in a Portuguese population of sCJD patients. J Neurol 2009;256:1540–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geschwind MD, Martindale J, Miller D, et al. Challenging the clinical utility of the 14-3-3 protein for the diagnosis of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Arch Neurol 2003;60:813–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pennington C, Chohan G, Mackenzie J, et al. The role of cerebrospinal fluid proteins as early diagnostic markers for sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurosci Lett 2009;455:56–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaudry P, Cohen P, Brandel JP, et al. 14-3-3 protein, neuron-specific enolase, and S-100 protein in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1999;10:40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamlin C, Puoti G, Berri S, et al. A comparison of tau and 14-3-3 protein in the diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurology 2012;79:547–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meiner Z, Kahana E, Baitcher F, et al. Tau and 14-3-3 of genetic and sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease patients in Israel. J Neurol 2011;258:255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skillback T, Rosen C, Asztely F, Mattsson N, Blennow K, Zetterberg H. Diagnostic performance of cerebrospinal fluid total tau and phosphorylated tau in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: results from the Swedish Mortality Registry. JAMA Neurol 2014;71:476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skinningsrud A, Stenset V, Gundersen AS, Fladby T. Cerebrospinal fluid markers in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res 2008;5:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geschwind MD, Tan KM, Lennon VA, et al. Voltage-gated potassium channel autoimmunity mimicking Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Arch Neurol 2008;65:1341–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong K, Forner S, Haman A, et al. CSF biomarkers findings in a large rapidly progressive dementia cohort. Neurology 2011;76:A551. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zerr I, Kallenberg K, Summers DM, et al. Updated clinical diagnostic criteria for sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain 2009;132:2659–2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meissner B, Kallenberg K, Sanchez-Juan P, et al. MRI lesion profiles in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurology 2009;72:1994–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.