Abstract

An overlap in the distribution of the 2 diseases (leishmaniasis and malaria) was reported in endemic areas, and it can cause significant delay in the diagnosis of leishmaniasis. Here, an 8-year-old Yemeni boy who was initially diagnosed as malaria and schistosomiasis, and later on as leishmaniasis is reported. He presented with prolonged fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and diarrhea. His blood film was positive for Plasmodium falciparum malaria, and his stool was positive for Schistosoma mansoni. Although a full therapeutic course of antimalarial and schistosoma was administered, his fever, weight loss, and increased hepatosplenomegaly continued. Bone marrow aspiration was carried out revealing Leishman-Donovan bodies (amastigote form). He was successfully treated with a full course of sodium stibogluconate. This case stresses the importance of alertness among the treating physicians to this disease occurring in a patient from an endemic area, presenting with prolonged fever, and hepatosplenomegaly.

Leishmaniasis is an infection caused by various leishmania species. It represents important public health problem in the Eastern Mediterranean Region of the World Health Organization (WHO), and is considered a neglected disease. Attention should be focused in controlling this disease. It tends to occur in some of these countries in sporadic outbreaks at approximately a 10-year interval.1 Visceral leishmaniasis, also known as kala-azar is a chronic infectious vector-borne disease caused by protozoa Leishmania donovani and Leishmania infantum, affecting the pediatric age after inoculation of the organism into the skin by a sandfly. It is considered as the second most alarming parasitic disease next to malaria.2 The incubation period ranges from 10 days to 24 months, with only a small percentage of infected persons manifesting the disease. In the initial period, the symptoms are fever, pallor, and hepatosplenomegaly, which are infrequently associated with coughing and diarrhea, and in some cases, could be oligosymptomatic. In the second period, the features are irregular fever, weight loss, and more enlarged spleen and liver, as well as deterioration in the individual’s general condition. In the final period of the disease, the features are severe malnutrition, pancytopenia (anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia), jaundice, and ascites. Mortality is often due to hemorrhagic or infectious complications.3 Our objective in presenting this particular case is to highlight the importance of taking into consideration visceral leishmaniasis in patients with prolonged fever and hepatosplenomegaly from endemic areas.

Case Report

An 8-year-old Yemeni boy was referred to Al-Sabeen Hospital (ASH), Sana’a, Yemen in December 2012 with prolonged febrile illness and hepatosplenomegaly for further management. He was from the rural area in Sana’a city, the eldest among 3 siblings; his siblings and parents were healthy. His complaints began 4 weeks prior to his referral. He developed vague intermittent abdominal pain, diarrhea on and off, and mild- to moderate-grade fever with chills and rigor. With time, his condition worsened. His fever continued, moderate to high-grade fever associated with rigor and chills, and his abdominal pain was persistent and severe accompanied with bloody diarrhea, and weight loss. Therefore, his family decided to seek medical advice. He was brought to a private clinic in Sana’a city. Laboratory investigations, including blood film for malaria parasite, urine analysis and culture, stool examination, and typhoid serology were carried out. Results of his test showed that his blood film was positive for Plasmodium falciparum, and Schistosomal ova (S. ova) were found in the stool. Oral chloroquine (400 mg) was given initially as a loading dose, followed by another 200 mg 6 hours later, and subsequently 200 mg daily for 2 more days. Also, a single dose of Praziquantel 50 mg per kilogram of body weight per day (mg/kg/BW/D) was given. He was treated adequately by antimalarial and schistosoma therapy, and both his blood film for malaria parasite and stool for schistosomal ova were negative. Even after all these medications, his condition did not improve, there was constant fever, malaise, poor appetite, abdominal discomfort, and he did not look well. He was brought to another private clinic where he was examined, and there, the attending physician gave him another antimalarial medication as he thought that he had resistance to the previous antimalarial drugs. Later, he was brought to another private clinic; he was given broad spectrum antibiotic, in addition to another antimalarial drug. This problem continued for 4 weeks without improvement and a final diagnosis. He was then transferred to ASH for further management where bone marrow aspiration was carried out, and he was diagnosed as visceral leishmaniasis.

On examination in ASH, he looked ill, lethargic, and had no jaundice. His weight was 20 kg, body temperature was 38.5°C, and pulse, respiratory rate, and blood pressure were within the normal range (NR). He had splenomegaly (spleen size, 10 cm), which was firm but not tender, and had enlarged liver (approximately 7 cm below the right subcostal margin, and the liver span was 14 cm) (Figure 1). Other systems were normal.

Figure 1.

Photograph of an 8-year-old patients’ abdomen revealing marked hepatosplenomegaly (arrows).

Laboratory investigations revealed hemoglobin was 8.0 g/dL, white blood cell count was 1,500 cells/mm3 (NR - 4000 cells/mm3) with a differential count of 57% polymorphs (NR - 40-70%), 41% lymphocytes (NR - 20-45%), and 2% monocytes (NR - 2-10%). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (Westergren) was 76 mm in the first hour, platelet count was 70×103/µL), and reticulocyte count was 0.5%. Peripheral smear showed normocytic normochromic anemia with leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia. Total bilirubin was 1.7 mg/dL, direct bilirubin was 0.5 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was 110 U/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was 91 U/L, total protein was 5.2 g/dL, serum albumin was 2.5 g/dL, and serum globulin was 2.7 g/dL. Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and anti-hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) tests were negative using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Urinalysis, blood urea, and creatinine were normal. Blood and urine cultures, and Widal test were negative. The chest x-ray was normal. Ultrasound of the abdomen showed splenomegaly and hepatomegaly. Bone marrow aspiration revealed Leishman-Donovan bodies (amastigote form) (Figure 2). He was diagnosed as visceral leishmaniasis.

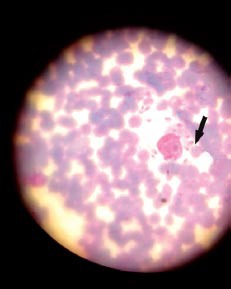

Figure 2.

An 8-year-old boy bone marrow patient’s aspirate showing amastigotes of Leishmania (Leishman-Donovan bodies) (arrow).

Sodium stibogluconate was started 20 mg/kg/BW/D and continued for 21 days. After a few days of sodium stibogluconate therapy, there was observed clinical improvement, his mood and condition improved, and the fever and abdominal discomfort subsided. Laboratory findings during the course of the treatment showed spontaneous recovery of all the results; hemoglobin, total white blood cell count, platelet count, and so forth. The bone marrow examination was not repeated. He was followed up regularly at the clinic, and after 4 months at discharge, he was examined, and there was complete remission of the symptoms and weight gain with remarkable regression of the spleen and liver.

Discussion

Visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) is a serious disease, which is lethal if left untreated. It occurs in irregular, periodic epidemics. Visceral leishmaniasis affects older children and young adults in Asia and Africa. Yemen is an endemic area for Leishmaniasis, malaria, and schistosomiasis.4-6 We present a case of a young boy who had long-standing fever and hepatosplenomegaly that was first diagnosed as malaria and schistosomiasis. Four weeks later, he was eventually diagnosed as leishmaniasis. The delayed diagnosis of leishmaniasis occurred as a result of the association of the 3 diseases at the same time, and the positive malaria test directed the treating physicians of this disease to antimalarial drug resistance.

Visceral leishmaniasis should be strongly suspected in patients with prolong fever, weakness cachexia, marked hepatosplenomegaly, and pancytopenia that have potential exposure in an endemic area. An overlap in the distribution of the 2 diseases (Leishmaniasis and malaria) were reported,7 but the 3 diseases together was not previously reported.

The diagnosis of leishmaniasis depends on, either the microscopical demonstration of Leishmania amastigotes in the applicable tissue aspirates or the biopsies, such as bone marrow, spleen, lymph nodes, or liver. The diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis in our case was carried out on the basis of bone marrow aspiration, which provided clear evidence of Leishman-Donovan bodies. Bone marrow aspiration is considered as a more acceptable method of diagnosis, less dangerous with no major problems, although it has a sensitivity of less than splenic aspirate.8 Bone marrow biopsy results can also be useful for assessing the prognosis of leishmania patients in terms of improvement of affected marrow cells. The result of treatment appears to be excellent in cases of hypercellular marrow.8 Treatment consists of antileishmanial therapy; the main limitation rgarding the choice of antileishmanial drug is cost and availability. For the case under discussion, sodium stibogluconate was used as it is more readily available and cheap. Our patient completed a total course of 21 days (20 mg/kg of sodium stibogluconate per day). Pentavalent antimony like sodium stibogluconate and meglumine antimoniate remains the first-line treatment in all regions of the developing world following decades of clinical experience. It has confirmed efficacy, with a greater than 90% of long-term cure rate, and affordable cost.

Repeated course of therapy may be necessary in patients with severe visceral leishmaniasis. Supportive therapy to manage nutritional status, associated anemia, hemorrhagic complications, and secondary infections is also important to optimize treatment outcomes. The development of resistance to first-line therapy requires the use of even more costly, and more toxic second-line drugs like amphotericin B.9,10

In conclusion, our case was successfully treated for malaria, schistosomiasis, and later on for leishmaniasis despite the delay in the diagnosis. The association of visceral leishmaniasis, malaria, and schistosomiasis can be the cause of delayed diagnosis. Visceral leishmaniasis must be taken into consideration in the differential diagnosis of prolonged febrile illness and hepatosplenomegaly. This case alerts general practitioners, pediatricians, and health authorities to the possibilities of the presence of visceral leishmaniasis together with other endemic diseases.

Acknowledgment

The author gratefully acknowledges and sincerely thank Mr. Ameen Bin Mohanna and Mr. Mohammed Bin Mohanna for their contribution in the preparation of this case report.Also all the laboratory technicians and all team working in the Al-Sabeen Hospital (ASH), Sana’a, Yemen section who participated in the study.

References

- 1.Sundar S, Rai M. Laboratory diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9:951–958. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.5.951-958.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jha PK, Vankalakunti M, Siddini V, Babu K, Ballal SH. Postrenal transplant laryngeal and visceral leishmaniasis - A case report and review of the literature. Indian J Nephrol. 2012;22:301–303. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.101259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silva GA, Boechat Tde O, Ferry FR, Pinto JF, Azevedo MC, Carvalho Rde S, et al. First case of autochthonous human visceral leishmaniasis in the urban center of Rio de Janeiro: case report. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 2014;56:81–84. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652014000100013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sady H, Al-Mekhlafi HM, Mahdy MA, Lim YA, Mahmud R, Surin J. Prevalence and associated factors of schistosomiasis among children in Yemen: implications for an effective control programme. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hotez PJ, Savioli L, Fenwick A. Neglected tropical diseases of the Middle East and North Africa: review of their prevalence, distribution, and opportunities for control. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bamaga OA, Mahdy MA, Mahmud R, Lim YA. Malaria in Hadhramout, a southeast province of Yemen: prevalence, risk factors, knowledge, attitude and practices (KAPs) Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:351. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ab Rahman AK, Abdullah FH. Visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) and malaria coinfection in an immigrant in the state of Terengganu, Malaysia: A case report. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2011;44:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wise-Draper T, Besa EC, Sacher RA, Vergidis D. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy. [Updated 2013 Feb 21. cited 2015 Jan 5] New York (NY): MEDSCAPE; 2013. Available from: http: //emedicine.medscape.com/article/207575-overview . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mishra J, Dey A, Singh N, Somvanshi R, Singh S. Evaluation of toxicity and therapeutic efficacy of a new liposomal formulation of amphotericin B in a mouse model. Indian J Med Res. 2013;137:767–776. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haldar AK, Sen P, Roy S. Use of Antimony in the Treatment of Leishmaniasis: Current Status and Future Directions. Mol Biol Int. 2011;2011:e571242. doi: 10.4061/2011/571242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]