Abstract

Lipomas are the most frequent soft tissue tumors. Osteolipomas are a rare variant that can be difficult to diagnose. We report the case of a 66-year-old man consulting with a tumor of 2 years development in the right paravertebral cervical region. Neurologically, the patient had no sign of myelopathy or neurological focality. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a mass with a lipid component and calcifications inside within the right paravertebral musculature with a possible origin in the right C3 posterior root. A computed tomography scan and guided biopsy were performed, revealing hematic material and small bone spicules with no apparent neoplastic element. The tumor was totally removed, including the right C3 posterior branch, and was confirmed to be an osteolipoma on biopsy. The patient remains asymptomatic at 6-month follow-up. The osteolipoma is a benign tumor of soft tissue, characterized by lipoma areas with mature bone tissue differentiation, and even with hematopoietic marrow.

Keywords: Atypical lipoma, Cervical paravertebral, Soft tissue tumor, Ossifying lipoma

Introduction

Lipomas are the most frequent soft tissue tumors [1]. They can appear in any location, but are usually found in subcutaneous regions, often in the soft adipose tissue of the neck, back, and extremities [2]. They occur most commonly in adults. On gross examination, they are tan-to-yellow lobulated masses with thin strands of intervening fibrous septae.

Lipomas can include a variety of other mesenchymal elements, leading to neoplasms, such as fibrolipomas, angiolipomas, chondrolipomas, and ossifying lipomas (osteolipomas) [3]. Lipomas that are ossified are most often within or adherent to adjacent bone, known as interosseous or perosteal lipomas, respectively [4].

When a lipoma independent of a bone undergoes ossification, it is referred to as an ossifying lipoma or an osteolipoma. This is a rare variant that can be difficult to diagnose using imaging methods and they can be challenging to differentiate from benign lipomas [5].

Case Report

We report the case of a 66-year-old man with a history of diabetes and hepatic steatosis, who was referred to the Department of Orthopedics for the evaluation and treatment of a tumor in the right paravertebral cervical region.

He had first noted the tumor more than 2 years earlier, and it had grown slowly since then without symptoms until a few months ago, when he experienced pain and dizziness. He had no family history and had not suffered any severe trauma or irradiation of the region.

On physical examination, we found a hard tumoration, adhered to deep planes, well demarcated, large in size, and without other signs. The patient had full neck range of motion. Neurologically, the patient showed no sign of myelopathy or neurological focality, only occasional dizziness with cervical flexion.

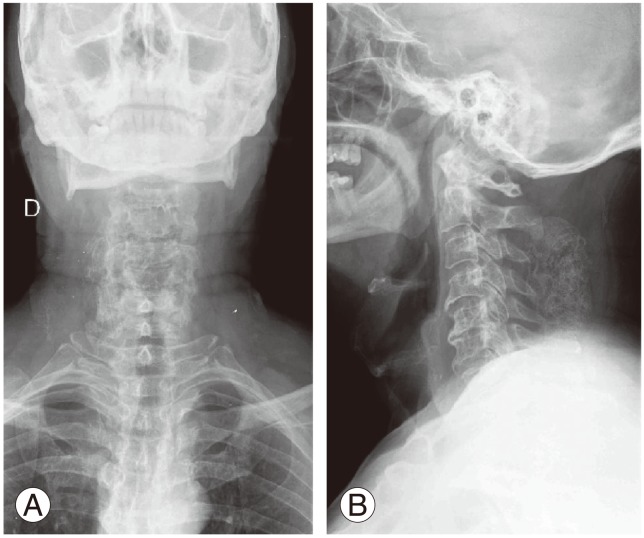

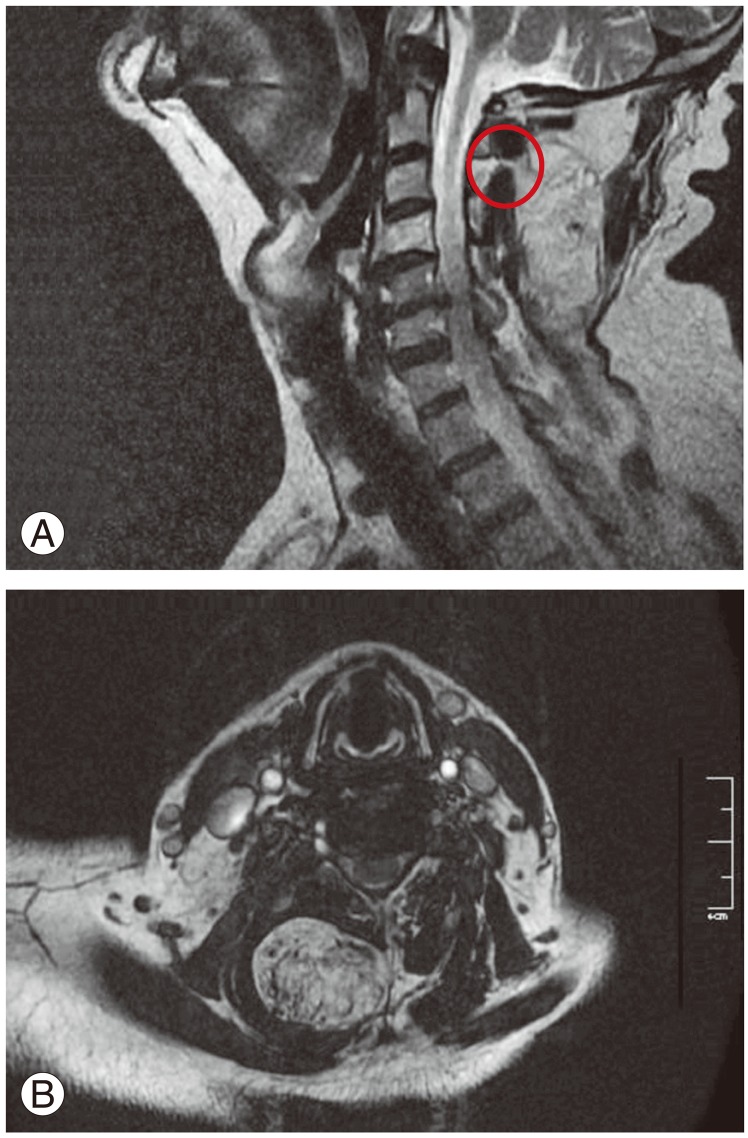

Diagnostic imaging, including plain radiograph and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), was obtained before referral. Plain radiographs demonstrated an about 8×3×4 cm calcified, right-sided, paravertebral mass posterior to C2-C6 (Fig. 1). The MRI showed a 10×3 cm mass with a lipid component and calcifications inside within the right paravertebral musculature that could have originated in the right C3 posterior root (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. (A, B) Plain radiographs indicating the calcified paravertebral mass.

Fig. 2. (A, B) Magnetic resonance imaging showing the lipid component and calcifications of the tumor within the right paravertebral musculature and showing the relationship with the right C3 posterior root (circle).

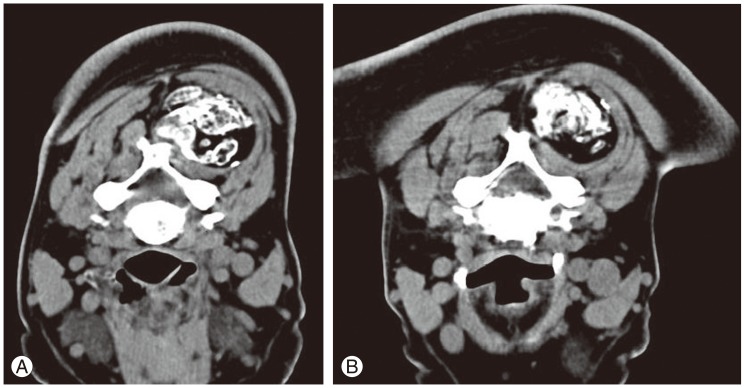

A computed tomography (CT) scan was ordered for further characterization. The CT showed a well-delineated, encapsulated 73×28×38 mm mass with fat tissue and an important calcifying tissue independent of the vertebrae (Fig. 3). In the CT scan, the calcifications did not appear chondroid or osteoid. To make a diagnosis, we performed CT-guided biopsy that revealed hematic material and small bone spicules with no apparent neoplastic element.

Fig. 3. (A, B) Computed tomography showing the mass with fat tissue and calcifying tissue independent of the vertebrae.

Without knowing clearly the origin of the tumor (lipomatous, neurogenic, or osteocondroid), we decided on surgery, after performing an excisional biopsy due to the seemingly benign characteristics on punch biopsy and absence of any associated toxic syndrome.

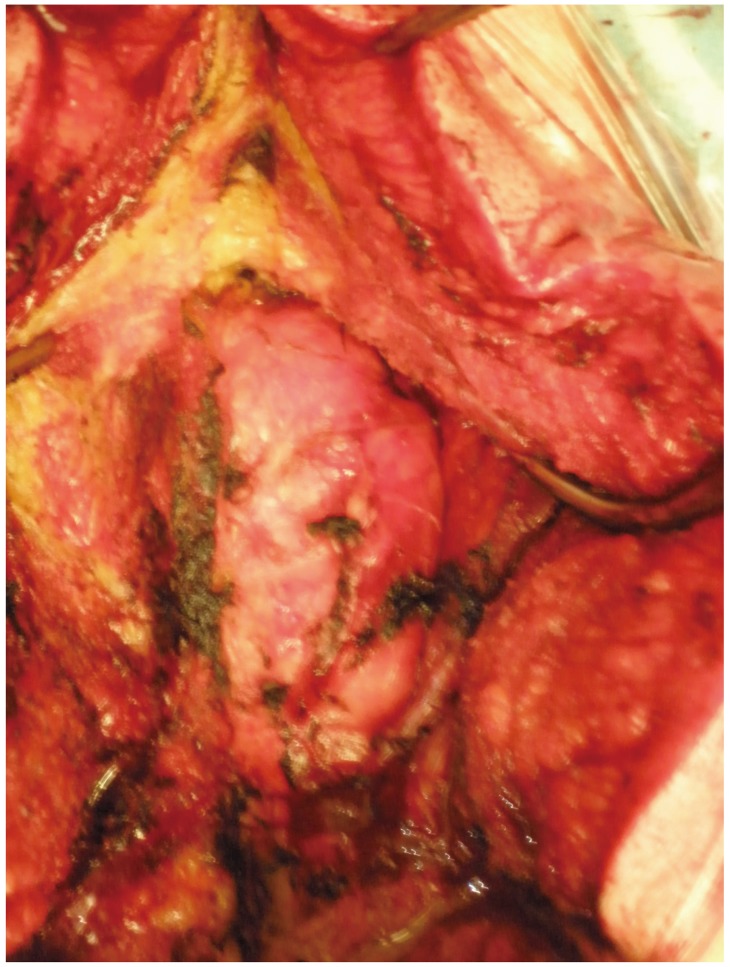

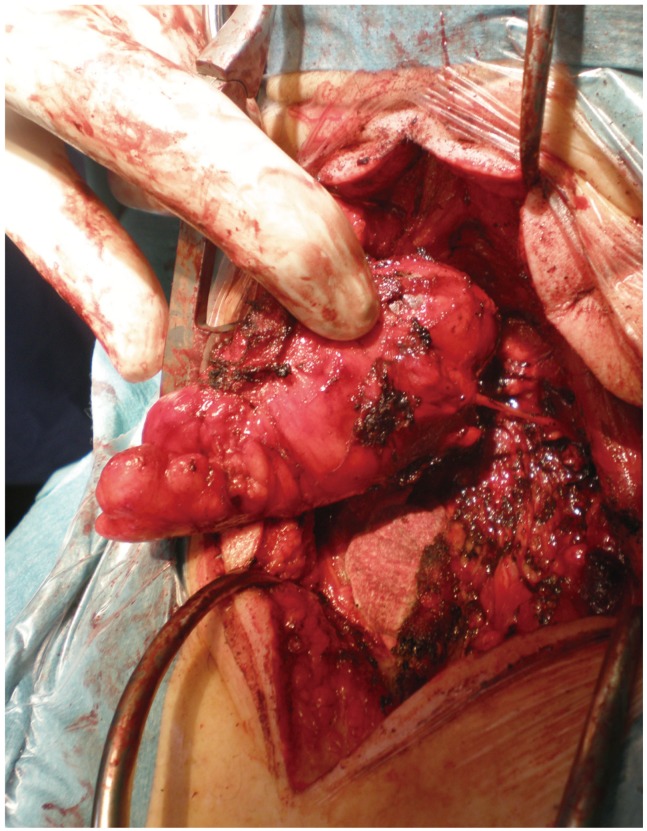

Intraoperatively, a mass of 5×10 cm, beginning at the height of C2 and T1 coming up on the right side was observed (Fig. 4). It showed calcifications and seemed to be associated with the right C3 posterior nerve (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. Intraoperative picture showing the position of the paravertebral mass.

Fig. 5. Intraoperative picture showing the relationship between the C3 posterior root and the paravertebral mass.

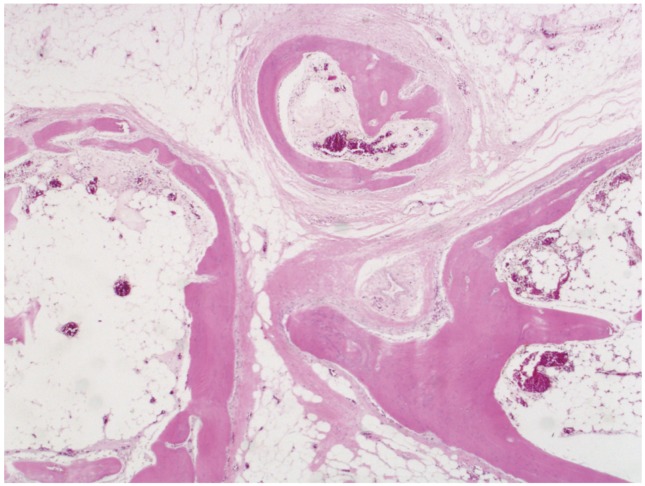

The final outcome of the pathology revealed mature adipose tissue proliferation with presence of trabecular bone and hematopoietic bone marrow (Fig. 6). Lamelar bone tissue contained areas of osteoid and plexiform bone tissue, including the presence of a small amount of hyaline cartilage. Thus, this benign lipoma was diagnosed as an osteolipoma. The tumoration included the right C3 posterior branch of the nerve, confirmed by the pathologist, to be normal peripheral nerve tissue. The patient's postoperative course has been uneventful, with no sign of recurrence at 6 months postoperatively.

Fig. 6. Picture showing mature adipose tissue proliferation with presence of trabecular bone and hematopoietic bone marrow (H&E, ×100).

Discussion

Lipomas are benign tumors, composed of mature adipose cells. The lipomatous component is always predominant in these lesions [2]. Ossification of these tumors is extremely rare, and osseous changes independent of bone attachment is the most unique of the variants [6]. When a lipoma undergoes osseous changes (including mature bone tissue differentiation, even with hematopoietic marrow) without bony attachment and fatty tissue predominates, it is referred to as an osteolipoma or ossifying lipoma [1].

An osteolipoma presents as an asymptomatic, slow-growing, round or discoid mass with a soft or doughy consistency. Most cases go undetected for years because of the asymptomatic and indolent nature of this tumor [4]. Lipomas with osseous changes have the same prognosis as plain lipomas. Surgical excision is the recommended treatment [7]. The differential diagnosis includes benign tumors that may contain bone, including teratomas or dermoids. Tumor calcinosis and calcification in a bursa must also be considered [7]. Other conditions, such as ossifying fibromas, myositis ossificans, and osteosarcomas, have to be taken into consideration [5].

The histiogenesis of ossifying lipomas is still unclear. Some investigators have suggested that blood-borne monocytes or osteogenic factors convert fibroblasts into osteoblasts in a metaplastic response. Others have argued that systemic and local factors, such as microtrauma and mechanical stress, cause the changes. It has also been suggest by some authors that lipomas ossifying independent of bone are more likely to be mesenchymomas, in which pluripotent cells differentiate into both adipose and bone separately [4,8]

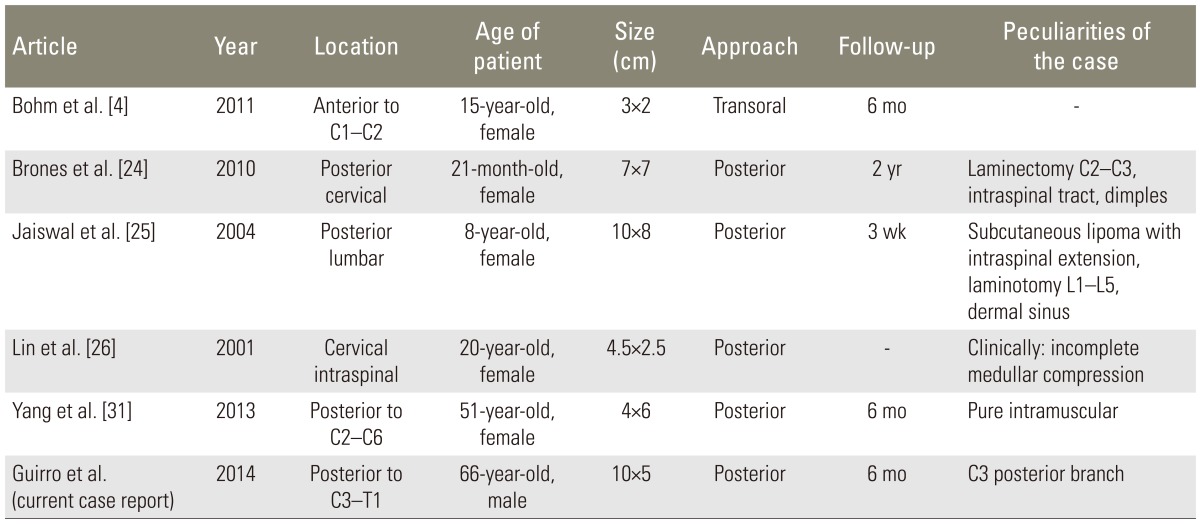

Lipoma with ossification was described for the first time in 1959 [9]. In a series of 635 lipomas seen over a 5-year period, only six cases with ossification were found [1]. Several sites have been reported: in the soft tissues of the trunk and the extremities [2,10,11,12], the joint space of the knee [13], the neck region [3] (including the retropharyngeal region [14], the parapharyngeal space [4,5,15,16], and the oropharynx [17]) the oral cavity (the most common site) [6,18,19,20,21,22], the skull base [23] and both the intraspinal [24,25,26] and intracranial cavities [27,28,29,30]. There only five cases described in the literature related directly to spine (Table 1); three of them were intraspinal osteolipomas [24,25,26], another was located in the anterior aspect of C1-C2, considered the neck region [4], and the most similar to our case report, was located intramuscularly at the paravertebral cervical spine [31]. Our case report is the first male with spine-related osteolipoma, found in the posterior aspect of the cervical spine, independent from the cervical vertebra, incorporating the C3 posterior branch.

Table 1. Published case report of osteolipomas directly related to spine.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Allen PW. Tumors and proliferations of adipose tissue: a clinicopathologic approach. New York: Masson Pub., USA; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Obermann EC, Bele S, Brawanski A, Knuechel R, Hofstaedter F. Ossifying lipoma. Virchows Arch. 1999;434:181–183. doi: 10.1007/s004280050324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kameyama K, Akasaka Y, Miyazaki H, Hata J. Ossifying lipoma independent of bone tissue. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2000;62:170–172. doi: 10.1159/000027741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohm KC, Birman MV, Silva SR, et al. Ossifying lipoma of c1-c2 in an adolescent. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31:e53–e56. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e31821f913c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bulkeley W, Mills OL, Gonzalvo A, Wong K. Osteolipoma of the parapharyngeal space mimicking liposarcoma: a case report. Head Neck. 2012;34:301–303. doi: 10.1002/hed.21534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adebiyi KE, Ugboko VI, Maaji SM, Ndubuizu G. Osteolipoma of the palate: report of a case and review of the literature. Niger J Clin Pract. 2011;14:242–244. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.84029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demiralp B, Alderete JF, Kose O, Ozcan A, Cicek I, Basbozkurt M. Osteolipoma independent of bone tissue: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:8711. doi: 10.4076/1757-1626-2-8711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Val-Bernal JF, Val D, Garijo MF, Vega A, Gonzalez-Vela MC. Subcutaneous ossifying lipoma: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:788–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plaut GS, Salm R, Truscott DE. Three cases of ossifying lipoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1959;78:292–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy NB. Ossifying lipoma. Br J Radiol. 1974;47:97–98. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-47-554-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandit HG, Bhosale PB, Khubchandani S. Ossifying lipoma of the thigh (a case report) J Postgrad Med. 1989;35:54–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teoh LC, Chan LK, Lai SH. Ossifying lipoma of the hand: a case report. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2001;30:536–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pudlowski RM, Gilula LA, Kyriakos M. Intraarticular lipoma with osseous metaplasia: radiographic-pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;132:471–473. doi: 10.2214/ajr.132.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blanshard JD, Veitch D. Ossifying lipoma. J Laryngol Otol. 1989;103:429–431. doi: 10.1017/s002221510010917x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minutoli F, Mazziotti S, Gaeta M, Vinci S, Mastroeni M, Blandino A. Ossifying lipoma of the parapharyngeal space: CT and MRI findings. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:1818–1821. doi: 10.1007/s003300000781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohno Y, Muraoka M, Ohashi Y, Nakai Y, Wakasa K. Osteolipoma in the parapharyngeal space. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1998;255:315–317. doi: 10.1007/s004050050067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider J, Swoboda R. Oropharyngeal lipoma with osseous metaplasia. Zentralbl Allg Pathol. 1987;133:249–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allard RH, Blok P, van der Kwast WA, van der Waal I. Oral lipomas with osseous and chondrous metaplasia; report of two cases. J Oral Pathol. 1982;11:18–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1982.tb00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dutescu N, Georgescu L, Hary M. Lipoma of submandibular space with osseous metaplasia. Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1973;35:611–615. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(73)90025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Godby AF, Drez PB, Field JL. Sublingual lipoma with ectopic bone formation. Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1961;14:625–629. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(61)90043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes CL. Intraoral lipoma with osseous metaplasia. Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966;21:576–578. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(66)90032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piattelli A, Fioroni M, Iezzi G, Rubini C. Osteolipoma of the tongue. Oral Oncol. 2001;37:468–470. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hazarika P, Pujary K, Kundaje HG, Rao PL. Osteolipoma of the skull base. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115:136–139. doi: 10.1258/0022215011907532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brones A, Mengshol S, Wilkinson CC. Ossifying lipoma of the cervical spine. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2010;5:283–284. doi: 10.3171/2009.10.PEDS0997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaiswal AK, Garg A, Mahapatra AK. Spinal ossifying lipoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12:714–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin YC, Huang CC, Chen HJ. Intraspinal osteolipoma. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:126–128. doi: 10.3171/spi.2001.94.1.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friede RL. Osteolipomas of the tuber cinereum. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1977;101:369–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinson G, Gennarelli TA, Wells GB. Suprasellar osteolipoma: case report. Surg Neurol. 1998;50:457–460. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(97)00152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wickremesekera AC, Christie M, Marks PV. Ossified lipoma of the interpeduncular fossa: a case report and review of the literature. Br J Neurosurg. 1993;7:323–326. doi: 10.3109/02688699309023819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wittig H, Kasper U, Warich-Kirches M, Dietzmann K, Roessner A. Hypothalamic osteolipoma: a case report. Gen Diagn Pathol. 1997;142:361–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang JS, Kang SH, Cho YJ, Choi HJ. Pure intramuscular osteolipoma. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2013;54:518–520. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2013.54.6.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]