Abstract

We report the case of a 25-year-old Iraqi woman who had multiple hospitalizations at an outside hospital for abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea without any evidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. Laboratory investigations finally showed a positive antinuclear antibody (1280), positive anti-dsDNA, anti-β2 glycoprotein I, low complement, positive Coombs tests, and leukopenia. A kidney biopsy showed ISN class II lupus nephritis. An ileal biopsy and angiogram were unremarkable. A computed tomography showed marked and dramatic bowel edema involving the small and large bowel (“target sign”), dilatation of intestinal segments, engorgement of mesenteric vessels (“comb sign”), and increased attenuation of mesenteric fat. These cardinal signs on computed tomography scan led to the correct diagnosis of lupus enteritis. Treatment was commenced with high-dose corticosteroids followed by mycophenolate mofetil, hydroxychloroquine, and then oral cyclophosphamide, but failed. The patient was eventually treated with the Euro-Lupus intravenous cyclophosphamide regimen, which resulted in significant clinical and radiological resolution.

Keywords: lupus enteritis, SLE

The differential for abdominal pain and diarrhea in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is vast and can include VIPoma, serositis, pancreatitis,1 intestinal vasculitis,2 protein-losing enteropathy,3 gluten enteropathy (celiac sprue),4–6 intestinal pseudo-obstruction,7 and infection.8 The pathology of lupus enteritis is thought to be immune-complex deposition and complement activation, with subsequent submucosal edema. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) is the most useful diagnostic tool and is key in leading to the correct diagnosis of lupus enteritis. We present a case of a woman with no history of SLE, but with a prolonged course of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and vomiting. Even after the eventual diagnosis of SLE with lupus enteritis, she failed multiple treatments. The case presentation highlights lupus enteritis as the first presentation of SLE, the importance of CT scanning in making the diagnosis, and the first use of the Euro-Lupus cyclophosphamide protocol for lupus enteritis.

CASE REPORT

A 25-year-old Iraqi woman was in her usual state of health until September 2009 when she developed early morning vomiting and stomach pain. She was afebrile. A CT of her abdomen and pelvis done during an emergency room visit to an outside hospital showed extensive small bowel thickening from the antrum of the stomach through to the distal ileum. The most significant thickening was in the jejunum. She was readmitted multiple times to the same outside hospital with recurrence of similar symptoms, including diarrhea more than 20 times a day and a 20-lb weight loss. An upper endoscopy showed gastritis with a normal biopsy of the antrum. A colonoscopy was negative. A subsequent colonoscopy revealed intestinal edema. Biopsy of the terminal ileum was normal as well. A subsequent upper endoscopy found edema of the stomach and duodenum. With anti-biotics, proton pump inhibitors, antiemetics, and bowel rest, the diarrhea lessened to 3 to 4 times a day.

During her fourth admission in November 2009, there was a faint red rash on her face and mild alopecia. A CT scan showed new areas of thickened bowel and diffuse ascites. She was treated with metronidazole for presumed infectious colitis. An exploratory laparotomy revealed ascites and thickening of the distal jejunum and ileum. Laboratory tests included mild proteinuria (312 mg per 24 hours), a positive antinuclear antibody (1:1280), positive anti-dsDNA, anti-β2 glycoprotein I, low complement, and positive Coombs test. A kidney biopsy showed ISN class II lupus nephritis. Complete blood count revealed leukopenia (3.3%) and anemia (hematocrit 27.7%).

She was diagnosed with SLE. Prednisone 40 mg daily was started. A mesenteric arteriogram did not show vasculitis. From December of 2009 through January 2010, she developed worsening diarrhea and abdominal pain and was readmitted to the outside hospital. A CT scan again showed small bowel inflammation and edema. Mycophenolate mofetil, hydroxychloroquine, and intravenous “pulse” methylprednisolone (1000 mg for 3 days) were prescribed. She had 2 flares after 3 months on 2 g of mycophenolate mofetil and 60 mg of prednisone. Every attempt to wean prednisone resulted in worsening diarrhea. The mycophenolate mofetil was titrated up to 2.5 mg/kg per day, but there was still no improvement. She was switched to oral cyclophosphamide. In September 2010, she was referred to our institution. We recommended monthly intravenous cyclophosphamide therapy. Her primary rheumatologist chose the Euro-Lupus intravenous cyclophosphamide protocol. The diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting lessened. She remained on azathioprine, with continued resolution of her abdominal pain and diarrhea. She did well until May 2011, when she discontinued her medications. Her symptoms returned and gradually worsened. By September 2012, she was admitted to an outside hospital with abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea. A CT scan of her abdomen and pelvis showed bowel wall edema. She was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone. She was discharged from the hospital on prednisone 20 mg. She did not follow up with her primary rheumatologist. Immunosuppressive therapy was not restarted at that time. She returned to our institution in October 2012, for a follow-up consultation. She was not having episodes of vomiting or diarrhea. She did have abdominal pain. We recommended that she restart azathioprine at 200 mg daily.

The final diagnosis of lupus enteritis was not made in our case without consideration of the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain and diarrhea in SLE including VIPoma, serositis, pancreatitis, intestinal vasculitis, protein-losing enteropathy, gluten enteropathy (celiac sprue), intestinal pseudo-obstruction, infection, salmonella, gonococcus, tuberculosis, and Clostridium difficile.9

In our patient, imaging was key in leading to the correct diagnosis of lupus enteritis. Arteriography may reveal arterial narrowing and distended loops of bowel in lupus enteritis,10 although it was not revealing in our patient. In a study of abdominal pain in SLE in which CT scans were performed, 79% had bowel pathology. Of the 31 cases, 29 had bowel wall thickening consistent with lupus enteritis. Of the 29 with bowel wall thickening, 26 had circumferential thickening (target sign). In 83%, the jejunum and ileum were affected.10

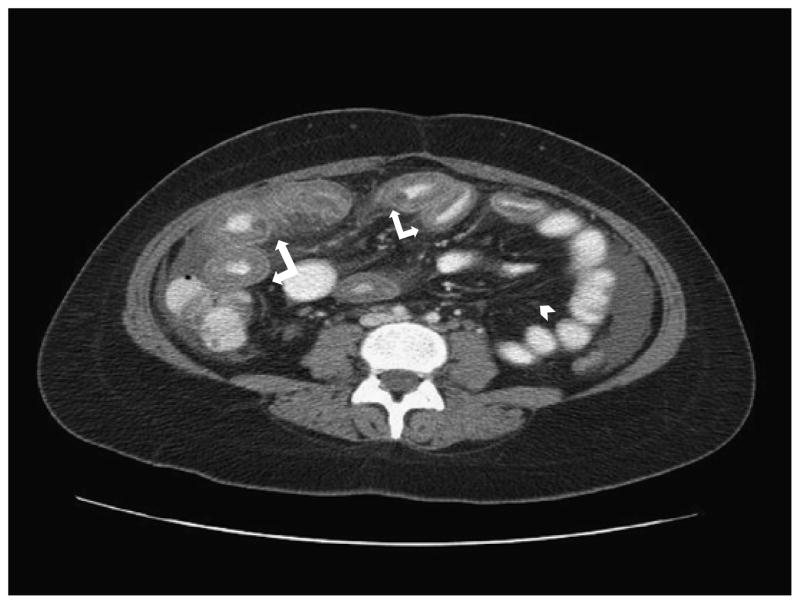

Lupus enteritis leads to 3 cardinal imaging signs on abdominal CT: (1) bowel wall thickening of greater than 3 mm (target sign) (Fig. 1) and dilatation of intestinal segments, (2) engorgement of mesenteric vessels (“comb sign”) (Fig. 2), and (3) increased attenuation of mesenteric fat11 (Fig. 1). Our patient’s CT findings were classic for the diagnosis of lupus enteritis and were instrumental in making the correct diagnosis. The CT of the abdomen showed marked bowel wall thickening, which was compatible with the target-sign appearance reported by Byun et al.10

FIGURE 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT scan of our patient showing severe diffuse multifocal bowel wall thickening, demonstrating the target sign (white arrows) and increased attenuation “haziness” of mesenteric fat (white arrow head).

FIGURE 2.

Contrast-enhanced CT scan with the comb sign (prominent engorgement of the mesenteric vessels with palisade or comblike arrangement) (white arrow).

This case was important because of the unusual presentation and treatment required to control the disease. The correct diagnosis, lupus enteritis, was not initially suspected because of the initial absence of signs of SLE and the rarity of lupus enteritis. Lupus enteritis was first described by Hoffman and Katz12 in 1980. It remains one of the rarest manifestations of SLE. It presents as abdominal pain (70%–100%), diarrhea (30%–60%), and vomiting (60%–80%).13 Lupus enteritis most often affects the jejunum and ileum. The rectum is rarely involved, because of collateral circulation. Histologically, both small vessel arteritis and venulitis have been described in lupus enteritis,14 although proof of vasculitis was not found in our case. In a reported case, biopsy of the resected jejunum revealed vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis involving small vessels in the submucosa. There was electron microscopic confirmation of immune deposits in the vessel walls of small capillaries. Immunofluorescence showed immunoglobulin in vessel walls.2 One proposed mechanism for lupus enteritis is complement activation.15 Exuberant systemic complement activation could promote diffuse microvascular injury and increased vascular permeability. Similar pathologic events could be present in the mesenteric circulation and produce features of lupus enteritis with intestinal capillary leakage, resulting in edema.15

Initial treatment for lupus enteritis is high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone and complete bowel rest.16 Additional immunosuppression with azathioprine or cyclophosphamide has been effective in some case reports.17 Even in patients who show a good initial response to treatment, relapse is common. A predictor of risk of recurrence for lupus enteritis is bowel wall thickness greater than 9 mm. Such patients may require longer courses of corticosteroids and/or addition of immunosuppressive drugs.18 Severe relapsing lupus enteritis has been treated successfully in 1 patient with a combination of cyclophosphamide and rituximab.19

Our patient failed mycophenolate and was then treated with oral cyclophosphamide. After her consultation at our institution, we recommended monthly intravenous cyclophosphamide using the National Institutes of Health regimen. Her primary rheumatologists chose the Euro-Lupus cyclophosphamide protocol instead.20 The Euro-Lupus trial found that a regimen of low-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide (cumulative dose 3 g), followed by azathioprine, was equivalent to the high-dose National Institutes of Health regimen for proliferative glomerulonephritis.20 Our patient is the first to receive the Euro-Lupus regimen for lupus enteritis. She received cyclophosphamide infusions every 2 weeks for 3 months. The diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting lessened. Treatment was then switched to azathioprine, with continued resolution of her symptoms, until she discontinued her medications

In summary, we present a case of a woman with no history of SLE, but with prolonged abdominal pain, diarrhea, and vomiting. Her CT scan was key in making the correct diagnosis of lupus enteritis. This is the first reported case of the use of the Euro-Lupus cyclophosphamide regimen for lupus enteritis.

Acknowledgments

L.W.S. is supported by a National Institutes of Health grant (T32 AR048522).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Makol A, Petri M. Pancreatitis in systemic lupus erythematosus: frequency and associated factors-a review of the Hopkins lupus cohort. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:341–345. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drenkard C, Villa AR, Reyes E, et al. Vasculitis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 1997;6:235–242. doi: 10.1177/096120339700600304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng WJ, Tian XP, Li L, et al. Protein-losing enteropathy in systemic lupus erythematosus: analysis of the clinical features of fifteen patients. J Clin Rheumatol. 2007;13:313–316. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31815bf9c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hrycek A, Siekiera U. Coeliac disease in systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report. Rheumatol Int. 2008;28:491–493. doi: 10.1007/s00296-007-0459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Courtney PA, Patterson RN, Lee RJ, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus and coeliac disease. Lupus. 2004;13:214. doi: 10.1191/0961203304lu512xx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rensch MJ, Szyjkowski R, Shaffer RT, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease autoantibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1113–1115. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mok MY, Wong RW, Lau CS. Intestinal pseudo-obstruction in systemic lupus erythematosus: an uncommon but important clinical manifestation. Lupus. 2000;9:11–18. doi: 10.1177/096120330000900104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shahram F, Akbarian M, Davatchi F. Salmonella infection in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 1993;2:55–59. doi: 10.1177/096120339300200110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diep JT, Kerr LD, Sarebahi S, et al. Opportunistic infections mimicking gastrointestinal vasculitis in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Rheumatol. 2007;13:213–216. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e318124fdf1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byun JY, Ha HK, Yu SY, et al. features of systemic lupus erythematosus in patients with acute abdominal pain: emphasis on ischemic bowel disease. Radiology. 1999;211:203–209. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.1.r99mr17203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee CK, Ahn MS, Lee EY, et al. Acute abdominal pain in systemic lupus erythematosus: focus on lupus enteritis (gastrointestinal vasculitis) Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:547–550. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.6.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman BI, Katz WA. The gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: a review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1980;9:237–247. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(80)90016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zizic TM, Shulman LE, Stevens MB. Colonic perforations in systemic lupus erythematosus. Medicine (Baltimore) 1975;54:411–426. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197509000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gladman DD, Ross T, Richardson B, et al. Bowel involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: Crohn’s disease or lupus vasculitis? Arthritis Rheum. 1985;28:466–470. doi: 10.1002/art.1780280419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belmont HM, Abramson SB, Lie JT. Pathology and pathogenesis of vascular injury in systemic lupus erythematosus. interactions of inflammatory cells and activated endothelium. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:9–22. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sultan SM, Ioannou Y, Isenberg DA. A review of gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38:917–932. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.10.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waite L, Morrison E. Severe gastrointestinal involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus treated with rituximab and cyclophosphamide (B-cell depletion therapy) Lupus. 2007;16:841–842. doi: 10.1177/0961203307081118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim YG, Ha HK, Nah SS, et al. Acute abdominal pain in systemic lupus erythematosus: factors contributing to recurrence of lupus enteritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1537–1538. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.053264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oh JS, Kim YG, Lee SG, et al. Successful treatment of recurrent lupus enteritis with rituximab. Lupus. 2010;19:220–222. doi: 10.1177/0961203309345787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houssiau FA, Vasconcelos C, D’Cruz D, et al. Immunosuppressive therapy in lupus nephritis: the Euro-Lupus Nephritis Trial, a randomized trial of low-dose versus high-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2121–2131. doi: 10.1002/art.10461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]