Abstract

Background and purpose

Postoperative urinary retention (POUR) is a clinical challenge, but there is no scientific evidence for treatment principles. We describe the incidence of and predictive factors for POUR in fast-track total hip (THA) and knee arthroplasty (TKA).

Patients and methods

This was a prospective observational study involving 1,062 elective fast-track THAs or TKAs, which were performed in 4 orthopedics departments between April and November 2013. Primary outcome was the incidence of POUR, defined by postoperative catheterization. Age, sex, anesthetic technique, type of arthroplasty, and preoperative international prostate symptom score (IPSS) were compared between catheterized and non-catheterized patients.

Results

The incidence of POUR was 40% (range between departments: 30–55%). Median bladder volume evacuated by catheterization was 0.6 (0.1–1.9) L. Spinal anesthesia increased the risk of POUR (OR = 1.5, 95% CI: 1.02–2.3; p = 0.04) whereas age, sex, and type of arthroplasty did not. Median IPSS was 6 in non-catheterized males and 8 in catheterized males (p = 0.02), but it was 6 in the females in both groups (p = 0.4).

Interpretation

The incidence of POUR in fast-track THA and TKA was 40%, with spinal anesthesia and increased IPSS in males as predictive factors. The large variation in perioperative bladder management and in bladder volumes evacuated by catheterization calls for randomized studies to define evidence-based principles for treatment of POUR in the future.

Postoperative urinary retention (POUR) can be defined as the inability to voluntarily empty the bladder after anesthesia and surgery (Kaplan et al. 2008). It is normally treated by catheterization of the bladder. However, the actual volume of urine in a bladder that would definitely require catheterization is unknown, which has resulted in different criteria for catheterization (Baldini et al. 2009). The reported incidence of POUR in elective total hip arthroplasty (THA) and elective total knee arthroplasty (TKA) ranges from 0% to 75% (Balderi and Carli 2010). POUR is a challenge in all surgical fields, not least in elective THA and TKA, and it may increase postoperative morbidity and prolong hospitalization (Choi and Awad 2013). Collaboration between urology specialists and other surgeons is therefore required to create evidence-based guidelines for POUR and its treatment. Several factors have been proposed to increase the risk of POUR (Baldini et al. 2009), and in this context, the international prostate symptom score (IPSS)—which is based on the symptom index for benign prostate hyperplasia developed by American Urological Association (Barry et al. 1992)—has been suggested for use in predicting the risk of POUR. However, published studies have shown substantial variation regarding their definition of POUR, their study design, and the level of detail, thus making them difficult to interpret and compare (Bjerregaard et al. 2014).

There are no large-scale, detailed data on the incidence of POUR in THA and TKA performed in standardized fast-track settings. Opioid-sparing postoperative analgesia and early mobilization may facilitate early restoration of bladder function (Bjerregaard et al. 2014), so the objective of this study was to determine the incidence of POUR—defined as the number of patients receiving intermittent urinary bladder catheterization—in 4 high-volume departments that perform fast-track THA and TKA. We also determined the influence of previously proposed risk factors for POUR and evaluated current practice for diagnosing and treating POUR in fast-track THA and TKA.

Patients and study design

We included data from 1,062 procedures of elective primary THA or TKA that were performed between April 3, 2013 and the November 26, 2013 in 4 Danish orthopedics departments that are part of the Lundbeck Foundation Center for Fast-Track THA and TKA (www.fthk.dk).

Inclusion criteria were age ≥ 18 years and informed oral consent. Exclusion criteria were refusal to participate, preoperative use of urinary bladder catheterization, hemodialysis, pregnancy, incapability of the patient to cooperate, placement of an indwelling catheter before surgery (n = 6), or inability to speak or understand Danish. 1,401 procedures of elective primary THA or TKA were performed during the study period and 1,062 of these were included in the study; logistic reasons (absence of research personnel, re-scheduling of operation dates etc.) prevented inclusion of approximately 10% of the patients. 50 patients were excluded postoperatively due to incomplete registration of data and the remaining patients were excluded on the basis of one or more of the exclusion criteria.

The design was a hypothesis-generating, prospective, non-interventional study with a pragmatically chosen sample size of 1,000 patients, as there had been no conclusive previous data on our primary outcome from a comparable population.

Perioperative care and urinary bladder management

Low-dose spinal anesthesia (with or without propofol sedation) was used as standard, but general anesthesia (GA) was offered if requested by the patient. Similar general regimens were used in all departments regarding anesthesia and surgical technique (Husted et al. 2010), and intraoperative fluid administration was restrictive, but was not recorded. Postoperative analgesia was accomplished by a multimodal approach of opioid-sparing oral treatment and perioperative local infiltration analgesia (Husted et al. 2010).

After surgery, the patients were observed in the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) until they fulfilled discharge criteria defined by the Danish Association for Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine (www.dasaim.dk). In the ward, mobilization was initiated within 2–6 hours postoperatively, and always on the day of surgery.

Urinary bladder volume was assessed in the postoperative period by trained nurses using ultrasound bladder scanners (BladderScan® BVI 3000, 6100, and 9400; Verathon Medical Europe BV, Ijsselstein, the Netherlands). Intermittent bladder catheterization was carried out in accordance with the local guidelines of the department. These were inability to empty the bladder voluntarily with a bladder volume of ≥ 400 mL (departments B–D, Table 1) or with a bladder volume of ≥ 600 mL (department A, Table 1). In cases of symptomatic urinary retention (inability to empty the bladder and abdominal discomfort, pain etc.), patients were catheterized in all departments.

Table 1.

Numbers of elective fast-track THAs and TKAs where urinary bladder catheterization was performed postoperatively, and their distribution between departments

| Department A (n = 230) | Department B (n = 226) | Department C (n = 310) | Department D (n = 296) | Total (n = 1,062) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intermittent catheterization | 81 (35.2%) | 127 (55.2%) | 132 (42.6%) | 89 (30.0%) | 429 (40.4%) |

| Repeated intermittent catheterization | 4 (1.7%) | 16 (7.1%) | 14 (4.5%) | 9 (3.0%) | 43 (4.1%) |

| Indwelling catheter because of POUR | 0 | 2 (0.9%) | 0 | 3 (1.0%) | 5 (0.5%) |

| Indwelling catheter not because of POUR | 4 (1.7%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.3%) | 2 (0.7%) | 8 (0.8%) |

POUR: postoperative urinary retention.

Data collection

Before surgery, all patients completed the 7 symptom-related questions of the IPSS, giving scores from 0 to 35 (Kaplan 2006). Age, sex, type of arthroplasty, anesthetic technique, and time of the last preoperative spontaneous micturition and the first postoperative one were registered for all patients. When there was postoperative bladder catheterization, we registered the volume of urine evacuated by the first intermittent catheterization, whether the intermittent catheterization was repeated, and whether a subsequent indwelling catheter was placed. Information on the department’s existing guidelines for postoperative bladder management was collected after the study, as we did not wish to affect current practice during the study period.

Outcome measures

Our primary outcome was the incidence of POUR, defined as the proportion of patients who received active intervention with intermittent urinary bladder catheterization in the postoperative period.

Secondary outcomes included the length of time from the last preoperative to the first postoperative spontaneous micturition, urinary volumes evacuated by intermittent bladder catheterization, distribution of risk factors for POUR (age, sex, anesthetic technique, and type of surgery) between catheterized patients and non-catheterized patients, and the association between preoperative IPSS and incidence of postoperative catheterization.

Statistics

Categorical data are given as number of patients and group percentage. Between-group comparisons were done using Fisher’s exact test. Odds ratio with 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated for statistically significant, dichotomous risk factors.

Continuous data are given as mean with range if they were approximately normally distributed (as assessed by histograms and probability plots), and as median and interquartile range (IQR) if they were not normally distributed. Groups were compared using the unpaired t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test where appropriate. IPSS scores were analyzed for the full scale, and also divided into 3 groups according to the severity of lower urinary track symptoms (LUTS): mild, 0–7; moderate, 8–19; and severe, 20–35 (Kaplan 2006). The 8 patients who received an indwelling catheter postoperatively for reasons other than urinary retention (Table 1) were not included in the analysis of risk factors.

IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 was used for data analysis, and any p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Ethics

According to Danish law, this was considered a quality-assurance project due to its non-interventional design. Thus, approval and need for written informed consent were waived by the local research ethics committee (registration no. H-1-2013-011). Collection and storage of data were approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (no. 2007-58-0015).

Results

The overall incidence of POUR was 40%, but it ranged from 30% to 55% between departments. Only 4% of the patients needed re-catheterization, and only 0.5% had an indwelling catheter due to POUR (Table 1).

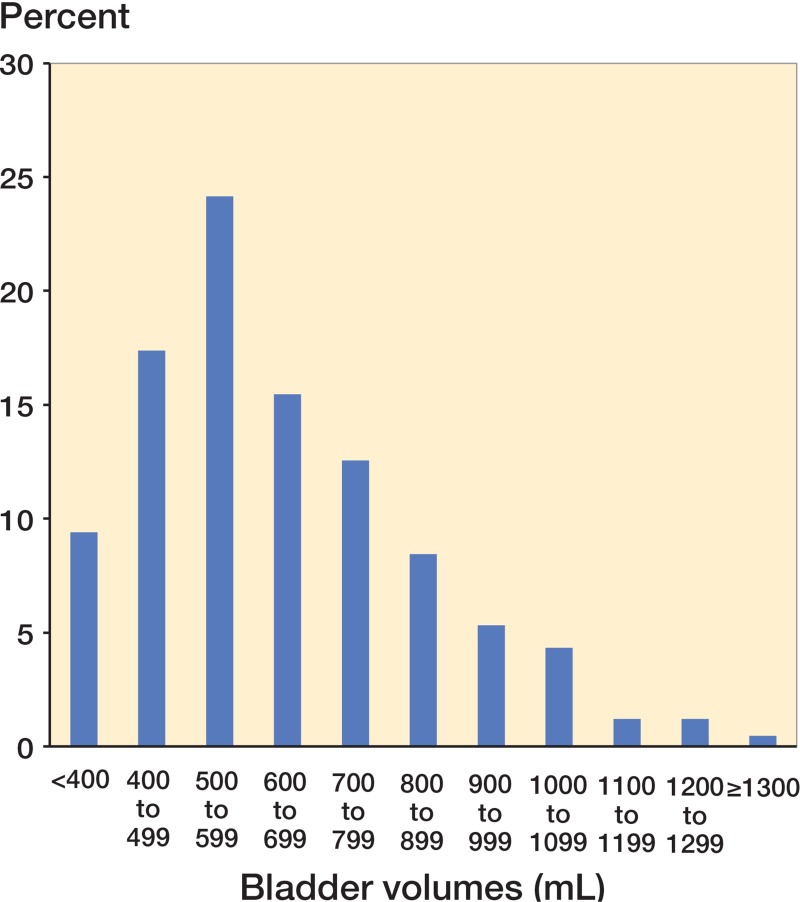

Median time between the last preoperative spontaneous micturition and the first postoperative one was 8 h and 10 min (IQR: 6:50–8:50) in the non-catheterized group and 10 h (IQR: 5:15–12:09) in the catheterized group. Bladder volumes evacuated by catheterization varied from 75 mL to 1,900 mL with a median volume of 550 mL (IQR: 450–703), and there were similar distributions between departments. 27% of the catheterized patients had bladder volumes of less than 500 mL, whereas 21% had bladder volumes of more than 800 mL (Figure). Mean age in the non-catheterized group was 67 years (range: 19–92) as compared to 68 years (range: 24–91) in the catheterized group (p = 0.9). Neither sex nor type of arthroplasty was related to postoperative catheterization (p = 0.2 and 0.5, respectively). The proportion of catheterized patients was statistically significantly higher in the spinal anesthesia group than in the GA group (41% vs. 31%; p = 0.04; OR = 1.5, CI: 1.02–2.3). Overall data on the role of risk factors are given in Table 2.

Urine volumes evacuated at the first intermittent catheterization postoperatively (n = 414).

Table 2.

Distribution of sex, type of arthroplasty, and anesthetic technique in catheterized and non-catheterized patients

| Catheterized (n = 424) | Non-catheterized (n = 630) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.2 | ||

| Male | 159 (37.5%) | 262 (41.6%) | |

| Female | 265 (62.5%) | 368 (58.4%) | |

| Type of arthroplasty | 0.5 | ||

| THA | 228 (53.8%) | 352 (55.9%) | |

| TKA | 196 (46.2%) | 278 (44.1%) | |

| Anesthetic technique | 0.04 | ||

| Spinal | 387 (91.3%) | 549 (87.1%) | |

| General | 37 (8.7%) | 81 (12.9%) |

THA: total hip arthroplasty; TKA: total knee arthroplasty.

In the total study population, median IPSS was 6 (IQR: 3–11) in the non-catheterized group and 7 (IQR: 3–12) in the catheterized group (p = 0.03). In males, median IPSS in the non-catheterized group was 6 (IQR: 2–11), as opposed to 8 (IQR: 4–13) in the catheterized group (p = 0.02). In females, median IPSS was 6 (IQR: 3–11) in both groups (p = 0.4). We found no statistically significant association between the 3 groups of IPSS severity and the risk of POUR—in the study population as a whole (p = 0.1) and when we analyzed males and females separately (p = 0.08 and 0.4, respectively) (Table 3). Comparison of patients with evacuated bladder volumes of less than 500 mL and those with bladder volumes of at least 500 mL showed no differences in IPSS scores or severity of IPSS (p > 0.05 for all patients, for males, and for females) (Table 3).

Table 3.

IPSS grouped according to severity, and compared between non-catheterized and catheterized patients, and also between patients catheterized for bladder volumes < 500 mL or ≥ 500 mL

| IPSS 0–7 | IPSS 8–19 | IPSS 20–35 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients, n | 603 | 367 | 70 | 0.1 |

| Catheterized | 226 (62.5%) | 166 (45.2%) | 26 (37.1%) | |

| Non-catheterized | 377 (37.5%) | 201 (54.8%) | 44 (62.9%) | |

| Catheterized patients, n | 220 | 162 | 25 | 0.5 |

| BV < 500 mL | 60 (27.3%) | 40 (24.7%) | 8 (30.8%) | |

| BV ≥ 500 mL | 160 (72.7%) | 122 (75.3%) | 18 (69.2%) |

IPSS: international prostate symptom score.

Missing data: IPPS was missing for 6 catheterized patients and 8 non-catheterized patients. Evacuated bladder volume was missing for 10 catheterized patients.

Discussion

With an overall incidence of postoperative urinary catheterization of approximately 40%, this is the first large-scale, prospective detailed study to report a qualified estimate of the incidence of POUR in fast-track THA and TKA. As previously stated, the incidence of POUR in THA and TKA has been imprecisely reported to be between 0% and 75% due to the highly variable criteria used to define POUR (Balderi and Carli 2010). 2 recent studies reported incidences of POUR of 25% and 30%, but the retrospective study defined POUR from bladder volumes of 500 mL or more (Balderi et al. 2011) whereas the prospective study defined POUR as abdominal discomfort, inability to micturate, and clinical evidence of an extended bladder (Kotwal et al. 2008). Neither of these 2 studies was performed in a fast-track setting and neither provided data on the bladder volumes evacuated by catheterization.

We found considerable differences between our 4 departments regarding the proportion of patients receiving catheterization, and there were considerable differences between departments regarding time of bladder scan and bladder volumes used as catheterization threshold, reflecting that no local or international consensus exists on evidence-based guidelines for defining and treating POUR.

Smaller prospective studies have indicated that male sex and high age are associated with an increased risk of POUR in patients undergoing lower limb arthroplasty (Sarasin et al. 2006, Kotwal et al. 2008), but this has not been confirmed in more recent retrospective studies with larger sample sizes (Balderi et al. 2011, Griesdale et al. 2011). We did not find increasing age or male sex to be clinically relevant risk factors for postoperative catheterization after fast-track THA or TKA. Previous studies have been inconclusive as to whether TKA is a risk factor for POUR compared to THA (Griesdale et al. 2011, Balderi et al. 2011), and in the present study we found that there was no difference in risk between patients undergoing THA and TKA.

We found that spinal anesthesia is a risk factor for POUR in fast-track THA and TKA, increasing the risk of postoperative catheterization by approximately 50% compared to GA. This is consistent with previous findings, and is in accordance with current knowledge on the physiology of the micturition reflex (Baldini et al. 2009, Choi and Awad 2013). Data on the use of low-dose, short-acting local anesthetics without opioid adjuvants are inconclusive (Choi and Awad 2013, Bjerregaard et al. 2014), and a recent smaller (but randomized) study has shown no difference in POUR rates in patients who receive spinal anesthesia and in those who receive GA (Harsten et al. 2013).

POUR is considered to be an acute, unobstructive urinary retention precipitated by surgery and/or anesthesia (Kaplan et al. 2008), and spontaneous remission should be expected when the precipitating stimuli are gone. Fast-track THA and TKA includes opioid-sparing analgesia and early mobilization, which might both facilitate restoration of bladder function (Kehlet 2013). In the present study, the median time from the last preoperative spontaneous micturition to the first postoperative one was approximately 8 hours in non-catheterized patients and approximately 10 hours in catheterized patients, and only 4.1% of the patients were catheterized more than once (Table 1). These findings indicate that POUR is a transient condition of relatively short duration in fast-track THA and TKA. Consistent with our findings, Balderi et al. (2011) reported a mean time from surgery to first spontaneous micturition of 6 hours and 25 minutes in the 213 patients (75%) who were not catheterized. Of the 73 patients (25%) who developed POUR, 18 had 1 single intermittent catheterization, 6 had 2 intermittent catheterizations, and the remaining 49 patients were treated with an indwelling catheter for 48 hours. No data were provided on time of the first spontaneous micturition in the POUR group (Balderi et al. 2011).

In our study, half of the catheterized patients had evacuated bladder volumes of between 500 mL and 800 mL, 21% had evacuated bladder volumes of more than 800 mL, and 7% had evacuated bladder volumes of more than 1,000 mL (Figure). As our study reflects clinical practice, some patients were catheterized based on clinical symptoms of urinary retention, and therefore independently of bladder volume—which is reflected by the fact that a smaller proportion (< 10%) had evacuated bladder volumes of less than 400 mL (Figure). We believe that urinary bladder volume is a central component in defining POUR, and non-evidence-based recommendations on bladder volumes for defining (and treating) POUR vary from 500 mL (Balderi and Carli 2010) to 600 mL (Balderi et al. 2011), mostly based on the assumption that over-distension of the bladder may cause detrusor damage and subsequently urological deficits (Baldini et al. 2009). However, the degree and duration of bladder distension that would cause chronic voiding difficulties in humans are unknown (Madersbacher et al. 2012). A recent review on perioperative micturition and POUR suggests that long-term sequelae are unlikely with over-distension of the bladder lasting less than 4 hours (Choi and Awad 2013), but this was based solely on the findings of Pavlin et al. (1999), without any more up-to-date data. Currently, no conclusive clinical data exist on the optimal interventional threshold for catheterization (Bjerregaard et al. 2014), so we hypothesize that a less aggressive strategy for postoperative bladder management—including acceptance of higher bladder volumes before catheterization—might avoid catheterization in many patients. However, clinical trials are needed to determine the long-term consequences and safety aspects of increasing the catheterization threshold.

The IPSS has been validated to quantify LUTS in men (Barry et al. 1992) and, although never validated in women, it has been proposed to be correlated with the bothersomeness of obstructive bladder symptoms in women (Groutz et al. 2000). We found statistically significant differences in preoperative IPSS scores between non-catheterized and catheterized male patients, but no differences in female patients. As mentioned above, the IPSS has not been validated in females, which may explain why it did not prove useful in predicting POUR. Our results are consistent with previously reported results from prospective observational studies on male patients undergoing THA and TKA (Elkhodair et al. 2005, Kieffer and Kane 2012), but they contradict the results of the study by Sarasin et al. (2006) who found that IPSS was not useful in predicting POUR regardless of sex and age (Sarasin et al. 2006). Although significant (p < 0.05), we found an absolute difference in median IPSS in males of only 2 points, and when grouping the IPSS values according to severity, we found no association between severity of symptoms and the risk of catheterization in either males or females, thereby calling into question the clinical applicability of IPSS for assessing the risk of POUR in fast-track THA and TKA. In addition, we compared IPSS scores in those who were catheterized for volumes < 500 mL and those who were catheterized for volumes ≥ 500 mL, but, irrespective of sex, we found no differences between these groups.

Our study had some limitations, as no detailed data were collected on preoperative morbidity and previous urogenital or gynecological surgery, which may affect perioperative micturition (Baldini et al. 2009). Also, due to the observational design, we did not provide uniform intraoperative procedures such as the technique for spinal anesthesia or fluid therapy, and no data were collected on intraoperative fluid administration. Since a positive intraoperative fluid balance may result in larger bladder volumes earlier in the postoperative period (where the “micturition reflex” may still not have been restored), it could result in a higher incidence of POUR. Future studies should include registration of intraoperative fluid therapy and fluid balance. Finally, there was great variability between the departments regarding the volumes of urine evacuated by catheterization (Figure), and a considerable proportion of patients were catheterized for a smaller volume than that recommended by the local guidelines. This means that some patients may have been catheterized unnecessarily, which is why we may have overestimated the real incidence of POUR.

In conclusion, the incidence of POUR in fast-track THA and TKA was 40% when defined by postoperative catheterization, but the lack of an evidence-based definition of POUR was reflected by considerable variation between the participating departments. Spinal anesthesia increased the risk of POUR, while age, sex, and type of arthroplasty did not. Although the IPSS was related to POUR, it had limited (if any) meaningful clinical applicability. Finally, POUR in fast-track THA and TKA was a transient and short-lasting condition with a risk of indwelling catheterization of only 0.5%. These results should serve as a basis for designing detailed, large, randomized controlled trials to provide high-quality data on the optimal bladder volume for postoperative catheterization in fast-track THA and TKA and other procedures. Such studies should be performed based on good collaboration between urologists, other surgeons, and anesthesiologists.

Acknowledgments

LB: statistical analysis, interpretation of data, and writing and revision of the manuscript. SB, SR, CT and UH: acquisition of data. AP: designing and planning of the study. PB and HK: designing the study, interpretation of data, and writing and revision of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript.

This study was financially supported by the Lundbeck Foundation (grant no. R25-A2702). The Lundbeck Foundation had no influence at any stage on the study process or on the content of the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Balderi T, Carli F. Urinary retention after total hip and knee arthroplasty . Minerva Anestesiol. 2010;76(2):120–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balderi T, Mistraletti G, D’Angelo E, Carli F. Incidence of postoperative urinary retention (POUR) after joint arthroplasty and management using ultrasound-guided bladder catheterization . Minerva Anestesiol. 2011;77(11):1050–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldini G, Bagry H, Aprikian A, Carli F. Postoperative urinary retention: anesthetic and perioperative considerations . Anesthesiology. 2009;110(5):1139–57. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819f7aea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, Jr., O’Leary MP, Bruskewitz RC, Holtgrewe HL, Mebust WK, Cockett AT. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association . J Urol. 1992;148(5):1549–57. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerregaard LS, Bagi P, Kehlet H. Editorial: Postoperative urinary retention (POUR) in fast-track total hip and knee arthroplasty . Acta Orthop. 2014;85(1):8–10. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2014.881683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Awad I. Maintaining micturition in the perioperative period: strategies to avoid urinary retention . Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2013;26(3):361–7. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32835fc8ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkhodair S, Parmar HV, Vanwaeyenbergh J. The role of the IPSS (International Prostate Symptoms Score) in predicting acute retention of urine in patients undergoing major joint arthroplasty . Surgeon. 2005;3(2):63–5. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(05)80063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesdale DE, Neufeld J, Dhillon D, Joo J, Sandhu S, Swinton F, Choi PT. Risk factors for urinary retention after hip or knee replacement: a cohort study . Can J Anaesth. 2011;58(12):1097–104. doi: 10.1007/s12630-011-9595-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groutz A, Blaivas JG, Fait G, Sassone AM, Chaikin DC, Gordon D. The significance of the American Urological Association symptom index score in the evaluation of women with bladder outlet obstruction . J Urol. 2000;163(1):207–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harsten A, Kehlet H, Toksvig-Larsen S. Recovery after total intravenous general anaesthesia or spinal anaesthesia for total knee arthroplasty: a randomized trial . Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(3):391–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Solgaard S, Hansen TB, Soballe K, Kehlet H. Care principles at four fast-track arthroplasty departments in Denmark . Dan Med Bull. 2010;57(7):A4166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan SA. Update on the american urological association guidelines for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Rev Urol. 2006;8(Suppl 4):S10–S17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan SA, Wein AJ, Staskin DR, Roehrborn CG, Steers WD. Urinary retention and post-void residual urine in men: separating truth from tradition . J Urol. 2008;180(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehlet H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty . Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1600–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer WK, Kane TP. Predicting postoperative urinary retention after lower limb arthroplasty . Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2012;94(5):356–8. doi: 10.1308/003588412X13171221591691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotwal R, Hodgson P, Carpenter C. Urinary retention following lower limb arthroplasty: analysis of predictive factors and review of literature . Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74(3):332–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madersbacher H, Cardozo L, Chapple C, Abrams P, Toozs-Hobson P, Young JS, Wyndaele JJ, De WS, Campeau L, Gajewski JB. What are the causes and consequences of bladder overdistension? ICI-RS 2011 . Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31(3):317–21. doi: 10.1002/nau.22224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlin DJ, Pavlin EG, Gunn HC, Taraday JK, Koerschgen ME. Voiding in patients managed with or without ultrasound monitoring of bladder volume after outpatient surgery . Anesth Analg. 1999;89(1):90–7. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199907000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarasin SM, Walton MJ, Singh HP, Clark DI. Can a urinary tract symptom score predict the development of postoperative urinary retention in patients undergoing lower limb arthroplasty under spinal anaesthesia? A prospective study . Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88(4):394–8. doi: 10.1308/003588406X106531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]