Abstract

Background and purpose

Pain sensitization may be one of the reasons for persistent pain after technically successful joint replacement. We analyzed how pain sensitization, as measured by quantitative sensory testing, relates preoperatively to joint function in patients with osteoarthritis (OA) scheduled for joint replacement.

Patients and methods

We included 50 patients with knee OA and 49 with hip OA who were scheduled for joint replacement, and 15 control participants. Hip/knee scores, thermal and pressure detection, and pain thresholds were examined.

Results

Median pressure pain thresholds were lower in patients than in control subjects: 4.0 (range: 0–10) vs. 7.8 (4–10) (p = 0.003) for the affected knee; 4.5 (2–10) vs. 6.8 (4–10) (p = 0.03) for the affected hip. Lower pressure pain threshold values were found at the affected joint in 26 of the 50 patients with knee OA and in 17 of the 49 patients with hip OA. The American Knee Society score 1 and 2, the Oxford knee score, and functional questionnaire of Hannover for osteoarthritis score correlated with the pressure pain thresholds in patients with knee OA. Also, Harris hip score and the functional questionnaire of Hannover for osteoarthritis score correlated with the cold detection threshold in patients with hip OA.

Interpretation

Quantitative sensory testing appeared to identify patients with sensory changes indicative of mechanisms of central sensitization. These patients may require additional pain treatment in order to profit fully from surgery. There were correlations between the clinical scores and the level of sensitization.

The proportion of osteoarthritis (OA) patients suffering from long-term pain after arthroplasty ranges from about 10% to 34% after total knee replacement (TKR) and from 7% to 23% after total hip replacement (THR) (Murray and Frost 1998, Vavrik et al. 2009, Beswick et al. 2012). Preoperative pain sensitization may be one of the reasons for persistent pain after technically successful TKR in up to 30% of patients (Murray and Frost 1998, Brander et al. 2003, Wylde et al. 2011). Earlier, pain in OA patients was only evaluated by using subjective questionnaires (Boeckstyns and Backer 1989, Gruener and Dyck 1994) and not by measurement of the somatosensory nervous system. A newer method of assessing sensory function—quantitative sensory testing (QST) (Gruener and Dyck 1994)—has since been implemented, providing a reliable, scientifically based method of measuring temperature and pressure and of pain thresholds. By using this standardized, computer-controlled method, small fiber function (Zaslansky and Yarnitsky 1998, Geber et al. 2009) and the corresponding central pathways can be measured. Thus, QST can detect sensory changes due to chronic pain (Rolke et al. 2006).

Patients with OA-related knee pain have shown a range of somatosensory abnormalities, with pressure hyperalgesia (Arendt-Nielsen et al. 2010, Wylde et al. 2012) and tactile hypoesthesia as the most prevalent (Wylde et al. 2012).

The pressure pain threshold (PPT) in the most painful area (Kosek and Ordeberg 2000) was found to be lower in hip OA patients who required surgery than in healthy control subjects; indeed, the PPT returned to normal after successful surgery (Kosek and Ordeberg 2000).

In patients who have been sensitized preoperatively, pain relief may fail postoperatively. Results from previous studies have shown that changes in nociception and central perception are maintained by chronic joint pain. Clinicians need to be able to select patients who are at risk according to easily assessable criteria. It would be easiest to use clinical scores to screen for pain sensitization without supplementary tests being required. To date, however, there have been no studies investigating whether there is any correlation between clinical functional scores and QST parameters preoperatively.

The purpose of this controlled cohort study was therefore to determine whether pain sensitization of knee and hip OA patients is related to joint function and clinical state preoperatively. Our data could be useful in identifying those patients who have been sensitized to pain. Such patients should be given more attention and perhaps a more intense multimodal pain therapy postoperatively in order to achieve a satisfactory clinical outcome.

Material and methods

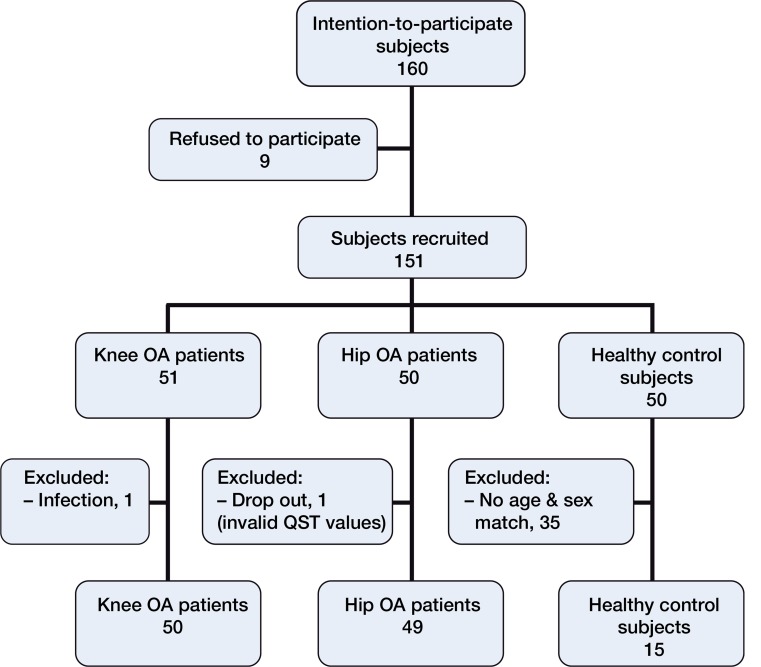

The patient groups are presented in Table 1. Initially, 50 healthy subjects were recruited at the same time as the patients. After age and sex matching, 15 subjects were included as a control group (median age 63 (54–70) years; 8 women) (Figure).

Table 1.

Clinical data on patients with knee and hip osteoarthritis (OA). Values are median (range)

| Variable | Knee OA n = 50 | Hip OA n = 49 |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (F/M) | 27/23 | 29/20 |

| Age, years | 66 (44–77) | 64 (40–77) |

| Visual analog scale | 2 (0–10) | 2 (0–10) |

| Duration of pain, years | 7 (0–30) a | 3 (0–20) a |

| FFbH-OA, points | 56 (6–86) | 56 (17–97) |

| AKSS 1, points | 41 (0–75) | - |

| AKSS 2, points | 50 (5–100) | - |

| Oxford knee score, points | 35 (19–53) | - |

| Harris hip score, points | 56 (15–82) |

p = 0.02.

FFbH-OA: functional questionnaire of Hannover for OA;

AKSS 1, 2: American Knee Society score 1, 2.

Flow diagram of recruitment of osteoarthritis (OA) patients and control subjects for quantitative sensory testing (QST).

In all patients, an orthopedic surgeon had prescribed total knee/hip replacement surgery because of painful OA. Patients with 1-compartment knee OA (for example, recipients of partial or retropatellar prostheses) were excluded. Other exclusion criteria for both groups were neurological and psychiatric diseases, infection of the joints being tested, bursitis trochanterica, chronic low back pain with referred pain into the joint under test, and severe other diseases. OA in other joints and replaced joints on the contralateral side or other joints in the lower extremities were not counted as exclusion criteria as long as these joints were not painful at the time of measurement.

Current medication, VAS for pain at the time of testing, and the total duration of pain were assessed. The patients were not advised to discontinue taking analgesics on the day of testing.

The following questionnaires were used: VAS, American Knee Society score 1 (knee rating, AKSS 1) and 2 (functional rating, AKSS 2), Oxford knee score (original version with the overall score from 12 to 60, with 12 being the best outcome), Harris hip score, and functional questionnaire of Hannover for osteoarthritis (FFbH-OA) (Hewitt et al. 2011).

Quantitative sensory testing

A battery of 4 thermal QST parameters was used: cold detection threshold (CDT), warm detection threshold (WDT), cold pain threshold (CPT), and heat pain threshold (HPT).

The palm of the non-dominant hand over the area of the thenar eminence was additionally chosen as a control region to detect hyper-/hypoalgesia independent of any pre-existing knee/hip pain (Mao 2002). One investigator performed all tests, in order to exclude different testers as a confounding factor. The temperature in the QST room was between 20°C and 23°C during testing (Hirosawa et al. 1984, Meh and Denislic 1994). Before the test, the patients were given 5 uninterrupted minutes in the quiet QST room to relax and enhance their concentration. The different testing devices and the test procedure were then explained in detail using a standardized information text.

QST was performed using the Thermal Sensory Analyzer TSA II (Medoc Inc., Ramat Ishai, Israel). A contact thermode (3 × 3 cm) was gently attached and secured with a band—first to the non-dominant hand and later to the lower skin surface of the distal patellar pole in knee OA patients or to the greater trochanter in hip OA patients. This was performed bilaterally, starting with the side that would not be operated on. The control subjects were tested at the palm of the non-dominant hand first, then at the left greater trochanter, and at the left distal patellar pole last.

From the baseline temperature of the thermode, 32°C, the temperature either increased or decreased continuously at a rate of 1°C per second. As a safety precaution, cut-off temperatures were set at a maximum of 50°C and minimum of 0°C. All temperature tests were then performed 3 times. The mean of the 3 measurements was used as an outcome parameter.

The testing started by determining CDT and WDT. Subjects were instructed to stop the stimulation when they first perceived a change in temperature. The temperature of the thermode was recorded when the stop button was pushed.

The testing continued by determining CPT and HPT, in that order. As the thermode temperature dropped/increased, the patients pressed the stop button as soon as they sensed discomfort.

The testing was completed by determining the pressure pain threshold (PPT) with a pressure algometer (FDN 100; Wagner Instruments, Greenwich, CT) calibrated to deliver between 100 and 1,000 kPa, corresponding to 0.1 kg applied weight, increasing at a rate of 0.5 kg/cm2s with a contact surface of 1 cm2. The patient was instructed to stop the algometer as soon as discomfort was sensed. 4 pressure measurements were taken at the same locations as the thermal thresholds; however, the first measurement was only performed to introduce the patient to the technique. The average of the last 3 measurements was used to calculate the pressure sensitivity. All PPT data are presented with the unit 100 kPa.

Statistics

If not otherwise stated, data are presented as median with range in parentheses. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 21.0. Measures of central tendency and dispersion were calculated for all variables, and goodness of fit to normal distribution was assessed by using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The Wilcoxon paired-rank test was used for comparisons between the 2 knees/hips within the patient groups, and the Kruskal-Wallis test and Mann-Whitney U-test (MWU test) were used for group comparisons. The Spearman correlation coefficient between the QST values and the clinical scores was calculated.

After logarithmic transformation of PPT, we performed z transformation as previously described (Wylde et al. 2012) in order to analyze the proportion of altered values. Furthermore, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were determined. Any z-scores outside the 95% CI of the data from healthy subjects were classified as altered.

The significance level was set at 5%. Due to the observational nature of the study, we did not perform adjustments for multiplicity issues within endpoints or for multiplicity caused by multiple endpoints.

Ethics

The investigation was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Heidelberg (study number 299/2006). The institutional review board approved the research protocol.

Results

Knee OA patients had been suffering from pain for a longer period than hip OA patients (Table 1). At the time of testing, 36 knee OA patients and 30 hip OA patients were taking pain medication. However, neither the pain medication nor the time since onset of the OA pain had any influence on the QST results. PPT values were lower in the affected knee and hip than in the joints of healthy subjects (Table 2). Altered PPT values were found at the affected joint in 26 of the 50 knee OA patients and in 17 of the 49 hip patients.

Table 2.

Quantitative sensory testing parameters on the affected and the healthy side in knee and hip osteoarthritis (OA) patients and controls (n = 15). Values are median (range)

| Variable a | OA patients | p-value b | Healthy controls | p-value c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knee OA (n = 50) | |||||

| PPT ak | 4.0 (0–10) | < 0.001 | 7.8 (4–10) | 0.003 | |

| PPT hk | 6.3 (2–10) | 0.2 | |||

| CDT ak | 28 (23–31) | 0.02 | 27 (13–30) | 0.08 | |

| CDT hk | 27 (20–31) | 0.8 | |||

| WDT align="left">ak | 38 (33–47) | 0.005 | 37 (34–48) | 0.4 | |

| WDT hk | 40 (34–49) | 0.03 | |||

| CPT ak | 2.6 (0–25) | 0.007 | 1.8 (0–10) | 0.2 | |

| CPT hk | 0 (0–22) | 0.5 | |||

| HPT ak | 47 (38–50) | 0.04 | 47 (42–50) | 0.7 | |

| HPT hk | 49 (41–50) | 0.1 | |||

| Hip OA (n = 49) | |||||

| PPT ah | 4.5 (2–10) | 0.06 | 6.8 (4–10) | 0.03 | |

| PPT hh | 4.7 (0–10) | 0.1 | |||

| CDT ah | 28 (19–31) | 0.7 | 28 (26–31) | 0.9 | |

| CDT hh | 29 (9–31) | 0.8 | |||

| WDT ah | 36 (34–47) | 0.8 | 37 (35–44) | 0.3 | |

| WDT hh | 36 (33–49) | 0.4 | |||

| CPT ah | 0 (0–30) | 0.7 | 0.2 (0–12) | 0.5 | |

| CPT hh | 0 (0–30) | 0.5 | |||

| HPT ah | 47 (37–50) | 0.006 | 47 (42–50) | 0.8 | |

| HPT hh | 48 (40–50) | 0.3 |

PPT: pressure pain threshold; CDT: cold detection threshold;

WDT: warm detection threshold; CPT: cold pain threshold;

HPT: heat pain threshold.

ak: affected knee, hk: healthy knee, ah: affected hip, hh: healthy hip

Affected side vs. healthy side.

Controls vs. patients.

Knee OA

PPT correlated with all clinical scores in the affected knee and the contralateral knee, and in the hand. In the affected knee, all QST thresholds were different from those in the contralateral knee (Table 2), with earlier detection and pain sensation (lower values for warmth/heat and higher for cold).

Hip OA

The clinical scores correlated with CDT in the affected hip, in the contralateral hip, and in the hand. HPT was lower in the affected hip than in the contralateral one (Table 2).

Discussion

Clinical scores

The most important finding of the present study was that PPTs were significantly lower in the affected joints of both knee OA patients and hip OA patients than in healthy control subjects. PPTs correlated with the knee scores and the FFbH-OA at all locations tested in knee OA patients, while the Harris hip score and FFbH-OA correlated with CDT in hip OA patients. QST parameters provided additional information as to whether a particular patient was already affected by a clinically relevant degree of sensitization. Furthermore, this method identified which sensory and nociceptive pathways were altered.

Our results suggest that poor clinical scores are highly likely to indicate pain sensitization. These patients would thus require a different kind of pain treatment in addition to conventional treatments such as medication and surgery. In addition, if an examiner’s clinical impression diverges from score values, QST tests could also help to monitor the patient’s condition and pain history. Joint function in OA patients is related to QST parameters.

PPT measured at the patellar tendon has been found to be a predictor in the VAS and in the pain section of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index in knee OA patients (Imamura et al. 2008). In the present study, the VAS score for pain was higher in those patients than in our knee OA patient group. Therefore, a higher degree of central sensitization could have developed.

OA patients compared to healthy subjects

We found lower PPT at the affected joint in knee and hip OA patients than in healthy subjects. These results confirm previous findings in knee OA patients (Wylde et al. 2011, 2012) and in hip OA patients (Kosek and Ordeberg 2000). However, neither hyperalgesia nor allodynia was found in patients with hand OA (Westermann et al. 2011). The impact of OA might therefore depend on the affected joint.

Previous studies have also found that the threshold for perceiving punctate stimuli is lower and brainstem activity is greater in hip OA patients than in controls, indicating central sensitization (Gwilym et al. 2009). Reduced PPT was previously interpreted as central sensitization (Imamura et al. 2008).

PPT values have varied least when testing for reliability in OA patients (Wylde et al. 2011). This could explain why we did not find more differences in the other QST parameters between OA patients and healthy controls. The relatively low pain level (measured by VAS) might also be another reason for relatively few QST differences being seen between healthy individuals and OA patients. Negative correlations between VAS and PPT (i.e. the higher the pain level, the lower the PPT) have been described (Arendt-Nielsen et al. 2010). Compared with previous studies in OA patients, pain level as measured by VAS was only moderate in our patients.

A small number of patients might also be suffering from neuropathy of small fibers that has not yet been diagnosed. Previously, localized pressure pain sensitization was found in one third of knee OA patients (Wylde et al. 2012). In our knee OA patient group, more than half of the patients showed altered PPT values after z-transformation. In our hip OA group, the proportion was smaller: only one third of the patients.

Pain treatment could be adapted and differentiated by knowing that different kinds of pain thresholds correlate with clinical scores in knee and hip OA patients. An elaborate regimen of acute pain therapy in the immediate postoperative phase may limit the development of chronic pain with a neuropathic component (Cousins et al. 2000). Classic pharmaceutical therapy involving NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, NMDA antagonists, cryotherapy, and regional anesthesia with additives is commonly used, with good evidence that such treatment reduces the need for opioids postoperatively. In TKR, femoral nerve block represents an additional treatment option (Parvizi et al. 2011). However, with regard to the importance of psychological and environmental factors in the chronification process (Cousins et al. 2000), additional treatment might be needed.

We did not assess psychological factors such as comorbidity with depression, which could possibly bias the results. However, in our department, TKR/THR is only prescribed by orthopedic specialists after other major sources of chronic pain have been excluded and clear functional restrictions found. When there is doubt, a psychological assessment is carried out in the pain management division before prescribing surgery. If “catastrophizing” behavior and comorbidities are found in that assessment, we recommend a multidisciplinary pain therapy in our pain management division. This multidisciplinary pain management is based on a bio-psychosocial treatment concept which involves physiotherapy, individual psychological and medical sessions, group sessions with relaxation techniques, behavioral training, general endurance and strength training, and other components. It is also offered to patients suffering from chronic, unexplained pain after TKR/THR—with good short- to medium-term results (Merle et al. 2014).

In summary, quantitative sensory testing appears to reveal and differentiate altered sensory and nociceptive pathways in knee and hip OA patients who show lower PPT than healthy control subjects. In the present study, more knee OA patients than hip OA patients showed signs of sensitization. Commonly used clinical scores showed a high correlation with QST parameters in both groups of OA patients. These results might help to optimize pain treatment for those OA patients with the worst score results. However, these patients would require additional pain treatment. Further studies should be conducted to validate this hypothesis.

Acknowledgments

All authors contributed substantially to the conception and design of the study, and reviewed the manuscript critically. BK and HW also contributed to acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data. BK, HW, and MS drafted the article. All the authors contributed to the final version of the paper.

We thank Annemarie Büttner for her contribution to data acquisition, Simone Gantz (Department of Orthopedics, Trauma Surgery and Spinal Cord Injury) and Tom Bruckner (Department of Medical Biometry, Heidelberg University Hospital) for statistical support, and Sherryl Sundell and Kayla Michael for English language revision.

Funding was received in part-support for the study presented in this article. The sources of funding were the Ministry of Science, Baden-Württemberg, Germany, and the German Arthritis Foundation (a non-profit organization).

No competing interests declared.

References

- Arendt-Nielsen L, Nie H, Laursen MB, Laursen BS, Madeleine P, Simonsen OH, et al. Sensitization in patients with painful knee osteoarthritis . Pain. 2010;149(3):573–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, Blom A, Dieppe P. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients . BMJ Open. 2012;2(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000435. e000435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckstyns ME, Backer M. Reliability and validity of the evaluation of pain in patients with total knee replacement . Pain. 1989;38(1):29–33. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brander VA, Stulberg SD, Adams AD, Harden RN, Bruehl S, Stanos SP, et al. Predicting total knee replacement pain: a prospective, observational study . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;416:27–36. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000092983.12414.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins MJ, Power I, Smith G. 1996 lecture: pain--a persistent problem . Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2000;25(1):6–21. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(00)80005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geber C, Scherens A, Pfau D, Nestler N, Zenz M, Tolle T, et al. Zertifizierungsrichtlinien für QST-Labore . Schmerz. 2009;23(1):65–9. doi: 10.1007/s00482-008-0771-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruener G, Dyck PJ. Quantitative sensory testing: methodology, applications, and future directions . J Clin Neurophysiol. 1994;11(6):568–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwilym SE, Keltner JR, Warnaby CE, Carr AJ, Chizh B, Chessell I, et al. Psychophysical and functional imaging evidence supporting the presence of central sensitization in a cohort of osteoarthritis patients . Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(9):1226–34. doi: 10.1002/art.24837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt DJ, Ho TW, Galer B, Backonja M, Markovitz P, Gammaitoni A, et al. Impact of responder definition on the enriched enrollment randomized withdrawal trial design for establishing proof of concept in neuropathic pain . Pain. 2011;152(3):514–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirosawa I, Dodo H, Hosokawa M, Watanabe S, Nishiyama K, Fukuchi Y. Physiological variations of warm and cool sense with shift of environmental temperature . Int J Neurosci. 1984;24(3)(4):281–8. doi: 10.3109/00207458409089817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura M, Imamura ST, Kaziyama HH, Targino RA, Hsing WT, de Souza LP, et al. Impact of nervous system hyperalgesia on pain, disability, and quality of life in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a controlled analysis . Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(10):1424–31. doi: 10.1002/art.24120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosek E, Ordeberg G. Abnormalities of somatosensory perception in patients with painful osteoarthritis normalize following successful treatment . Eur J Pain. 2000;4(3):229–38. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2000.0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J. Opioid-induced abnormal pain sensitivity: implications in clinical opioid therapy . Pain. 2002;100(3):213–7. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00422-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meh D, Denislic M. Quantitative assessment of thermal and pain sensitivity . J Neurol Sci. 1994;127(2):164–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)90069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merle C, Brendle S, Wang H, Streit MR, Gotterbarm T, Schiltenwolf M. Multidisciplinary treatment in patients with persistent pain following total hip and knee arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(1):28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray DW, Frost SJ. Pain in the assessment of total knee replacement . J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(3):426–31. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.80b3.7820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvizi J, Miller AG, Gandhi K. Multimodal pain management after total joint arthroplasty . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(11):1075–84. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolke R, Baron R, Maier C, Tolle TR, Treede RD, Beyer A, et al. Quantitative sensory testing in the German Research Network on Neuropathic Pain (DFNS): standardized protocol and reference values . Pain. 2006;123(3):231–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vavrik P, Landor I, Tomaides J, Popelka S. Medin modular implant for total knee arthroplasty--mid-term results . Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2009;76(1):30–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann A, Ronnau AK, Krumova E, Regeniter S, Schwenkreis P, Rolke R, et al. Pain-associated mild sensory deficits without hyperalgesia in chronic non-neuropathic pain . Clin J Pain. 2011;27(9):782–9. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31821d8fce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylde V, Hewlett S, Learmonth ID, Dieppe P. Persistent pain after joint replacement: prevalence, sensory qualities, and postoperative determinants . Pain. 2011;152(3):566–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylde V, Palmer S, Learmonth ID, Dieppe P. Test-retest reliability of Quantitative Sensory Testing in knee osteoarthritis and healthy participants . Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(6):655–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylde V, Palmer S, Learmonth ID, Dieppe P. Somatosensory abnormalities in knee OA. Rheumatology (Oxford) . 2012;51(3):535–43. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaslansky R, Yarnitsky D. Clinical applications of quantitative sensory testing (QST) . J Neurol Sci. 1998;153(2):215–38. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(97)00293-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]