Abstract

Background and purpose

Hypoxia, necrosis, and bone loss are hallmarks of many skeletal diseases. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBO) is often used as an adjunctive therapy in these cases. However the in vivo effect of HBO on osteoclast formation has not been fully established. We therefore carried out a longitudinal study to examine the effect of HBO on osteoclast formation and bone resorptive capacity in patients who were referred to the Plymouth Hyperbaric Medical Centre.

Methods

Osteoclast precursors were isolated from peripheral blood prior to and following 10 and 25 daily hyperbaric treatments (100% O2 at 2.4 atmospheres absolute ATA for 90 min) to determine osteoclast formation and resorptive capacity. The expression of key regulators of osteoclast differentiation RANK, Dc-STAMP, and NFATc1 was also assessed by quantitative real-time PCR.

Results

HBO reduced the ability of precursors to form osteoclasts and reduced bone resorption in a treatment-dependent manner. The initial suppressive effect of HBO was more pronounced on mononuclear osteoclast formation than on multinuclear osteoclast formation, and this was accompanied by reduction in the expression of key regulators of osteoclast formation, RANK and Dc-STAMP.

Interpretation

This study shows for the first time that in vivo, HBO suppresses the ability of monocytic precursors to form resorptive osteoclasts.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBO) is often used as an adjunct to repair damaged skeletal elements, and the consensus is that HBO may be valuable for the healing of refractory osteomyelitis and other necrotic skeletal disorders such as osteonecrosis of the jaw (Pasquier et al. 2004, Pitak-Arnnop et al. 2008, Goldman 2009), particularly in irradiated fields. HBO commonly consists of the patient breathing 100% oxygen at 2–2.4 atmospheres for 90–120 min, 5–6 days per week for 6–8 weeks, which elevates plasma oxygen, thus enabling a 10-fold increase in oxygen tension in areas of ischemic damage (Tibbles and Edelsberg 1996). This modifies cytokine production, angiogenesis, and the immune response to promote tissue regeneration (Gill and Bell 2004). Bone cells are also acutely sensitive to changes in oxygen tension with hypoxia stimulating osteoclast formation and suppressing osteoblast activity (Arnett et al. 2003, Utting et al. 2006). Previous studies have shown that HBO stimulates osteoblast activity (Muhonen et al. 2004, Wu et al. 2007); however, no study has examined the in vivo effect of HBO on the ability of human monocytes to form osteoclasts. This is surprising, considering the role of osteolysis in the pathogenesis of many inflammatory skeletal disorders. We therefore examined the ability of monocytic precursors to form bone resorptive osteoclasts ex vivo prior to and following HBO therapy. The effect of HBO on the intracellular mechanisms that regulate osteoclast formation was also examined.

Materials and methods

Media and reagents

Recombinant human RANKL and human M-CSF were purchased from Insight Biotechnology (Wembley, London, UK). Ampicillin, streptomycin, α-MEM culture medium, Histopaque-1077, and acetic acid were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Poole, Dorset, UK).

HBO treatment and venous blood collection

Blood samples were taken from consenting patients who were referred to the Plymouth Hyperbaric Medical Centre by their consultants for HBO. Samples were taken as detailed below, before and after HBO treatment to enable subjects to act as their own control. 6 male patients were recruited with an age range of 49–83 years; 3 were receiving HBO for chronic wound healing and the other 3 for radiation tissue damage. Patients were exposed to HBO daily inside a multiplace chamber, and they were provided with a sealed breathing hood from which they received 100% O2 at 2.4 ATA for 90 min, including 2 air breaks for 5 min each to minimize the risk of oxygen toxicity. The first blood sample was taken 1 h before the first HBO session (pre-HBO group) and subsequent samples taken before the patients had their eleventh treatment (10-treatment group) and twenty-sixth treatment (25-treatment group), about 21 h after HBO the previous day. Blood was collected into potassium-EDTA vacutainer tubes to prevent clotting and kept at room temperature until monocytes were isolated.

Isolation and culture of peripheral blood monocytes

Blood was diluted 1:1 in unsupplemented medium (α-MEM). Peripheral blood monocytes (PBMCs) were isolated by layering 15 mL α-MEM blood suspension on 25 mL histopaque-1077, and centrifuging at 400 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The buffy layer containing monocytes was removed and washed in 10 mL unsupplemented α-MEM, then centrifuged at 250 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was resuspended in culture medium containing 10% FCS and red cells were lysed using 10% acetic acid. PBMCs in the resulting suspension were counted using a hemocytometer. 1 × 104 PBMCs were then cultured in 96-well plates containing α-MEM supplemented with 50 ng/mL M-CSF (basal controls) or 50 ng/mL M-CSF and 30 ng/mL RANKL (all other groups). For the assessment of bone resorption, slices of devitalized cortical bovine bone were placed in the wells before the addition of cells. Culture was performed by incubating the plates at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cultures were fed every 2–3 days by replacing half the medium with fresh medium and cytokines. Experiments were stopped after 12 days to assess osteoclast differentiation by staining for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), and at 20 days for resorption (see below).

Assessment of osteoclast differentiation

Osteoclast formation was determined using the specific osteoclastic marker TRAP using a modification of Burstone’s methodology (Burstone 1958). After incubation, cells were fixed with 10% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min, washed with distilled water, and stained for TRAP using a leukocyte acid phosphatase kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma-Aldrich). The substrate used was napthol AS-BI phosphate and fast garnet GBS base was used as a chromogen. All incubations were performed in the presence of 0.05 mol/L sodium tartrate. The number of TRAP-positive and -negative cells was recorded at 5 predetermined sites in each well using a light microscope fitted with an eyepiece graticule (40× magnification). The number of TRAP-positive cells with 1 or 2 nuclei (mononuclear osteoclasts) or with 3 or more nuclei (multinuclear osteoclasts) was recorded for each site, and the mean number of multinuclear and mononuclear osteoclasts was calculated per cm2.

Assessment of bone resorption

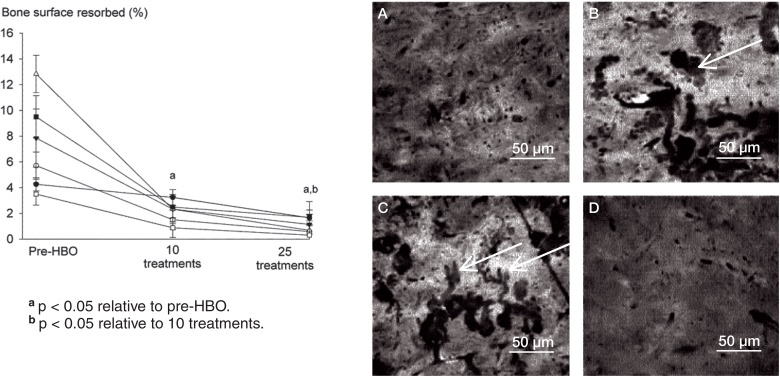

Slices of bovine cortical bone used as substrates for osteoclastic resorption were prepared as previously described (Fuller et al. 2002). After appropriate incubation, cells were removed from the surface of the bone slice by immersion in 10% sodium hypochlorite for 5 min, washed in distilled water for 5 min, and stained with 1% toluidine blue solution for 10 min. The slices were then air-dried and mounted on glass slides. The percentage of bone surface displaying resorption was assessed blind by a single researcher (HH), across the entire surface of each bone slice using reflected light microscopy at a magnification of 40×. Resorption pits appear clearly as darkly stained, clearly marginated areas using reflected light microscopy (Figure 2). An eyepiece graticule consisting of a 10 × 10 grid with 100 intersections was then used to quantify the percentage of the entire bone surface showing resorption, by counting the number of grid intersections overlying resorption pits.

Figure 2.

Daily exposure to HBO suppresses RANKL-induced bone resorption in a treatment number-dependent manner. Human PBMCs were incubated on bone slices in the presence of RANKL (30 ng/mL) and M-CSF (50 ng/mL) for 21 days. Following incubation, the percentage of bone surface displaying resorption pits was analyzed by reflected light microscopy. Control cultures (panel A), pre-HBO (B), 10 HBO treatments (C), and 25 HBO treatments (D). Values are mean ± SEM (n = 6).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) was used to detect gene expression of key regulators of osteoclast differentiation using the ΔΔCT methodology. PBMCs were plated in 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 106 cells per well and incubated for 11 days with a complete change of medium every 3–4 days. Total RNA was then isolated on the twelvth day of culture using a Sigma Genelute RNA isolation kit. RNA was quantified on a nanodrop spectrophotometer, and cDNA was produced using the ImPromII Reverse Transcription System (Promega). Real-time PCR was performed on a StepOne PCR system (Applied Biosystems) using the DNA-binding dye SYBR green for detection of PCR product. 2 µL of cDNA was added to a final reaction volume of 25 µL containing 0.05 U/µL Taq polymerase, SYBR green, and specific primers (0.2 µM each). The forward and reverse primer sets used for PCR were as follows:

β-actin, F: GCGCGGCTACAGCTTCA,

R: TGGCCGTCAGGCAGCTCGTA;

RANK, F: GGTGGTGTCTGTCAGGGCACG,

R: TCTCCCCCACCTCCAGGGGT;

Dc-STAMP, F: GTTGGCTGCCCTGCACCGAT,

R: TCCCTCATCCTGGGGCTGCC;

and NFATc1, F: GGTCTCGAACACTCGCTCTGCC,

R: GCAGTCGGAGACTCGTCCCTGC.

Cycling conditions were 95°C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 65°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds. Melting curve analysis was then performed.

Statistics

Equality of variance was determined using a Levene’s test prior to performing a 1-way ANOVA. Statistical differences between groups were then established using a Fisher’s least significant difference post hoc test for pairwise comparisons between means. The data correspond to independent observations from 6 separate subjects (n = 6). Any p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Statview statistical software (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA).

Ethics

All studies were approved by the Plymouth and Cornwall NHS Ethics Committee (REC number 09/H0203/57) and were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration. All subjects provided written informed consent.

Results

HBO suppresses osteoclast formation and bone resorption

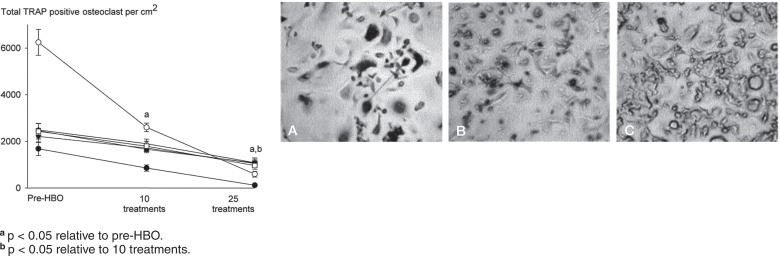

Daily HBO treatment reduced the ability of monocytes to differentiate into TRAP-positive osteoclasts in a treatment number-dependent manner (Figure 1). RANKL induced a 5-fold increase in the number of TRAP-positive osteoclasts relative to basal controls that were not treated with RANKL (data not shown). 10 HBO treatments suppressed the total number of TRAP-positive cells in all subjects (60% of pre-HBO), with 25 treatments having an even greater suppressive action (20% of pre-HBO) (Figure 1). Similar effects of HBO were noted on the resorptive activity of osteoclasts. As expected, osteoclasts produced characteristic resorption pits after 20 days, which was reduced in a treatment-dependent manner by HBO (Figure 2). 10 HBO treatments reduced bone resorption area to 20% of that seen in pre-HBO cultures, and resorption was further reduced after 25 treatments (being 10% of pre-HBO values) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Daily HBO therapy suppresses RANKL-induced osteoclast formation in a treatment number-dependent manner. Human PBMCs were incubated in the presence of RANKL (30 ng/mL) and M-CSF (50 ng/mL), stained for TRAP, and the total number of TRAP-positive osteoclasts quantified. Representative images of RANKL-treated TRAP-stained cultures from pre-HBO group (panel A), 10 HBO exposures (B), and 25 HBO exposures (C) (magnification ×40). Arrows show examples of multinucleated osteoclasts and arrowheads show examples of mononuclear osteoclasts. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6).

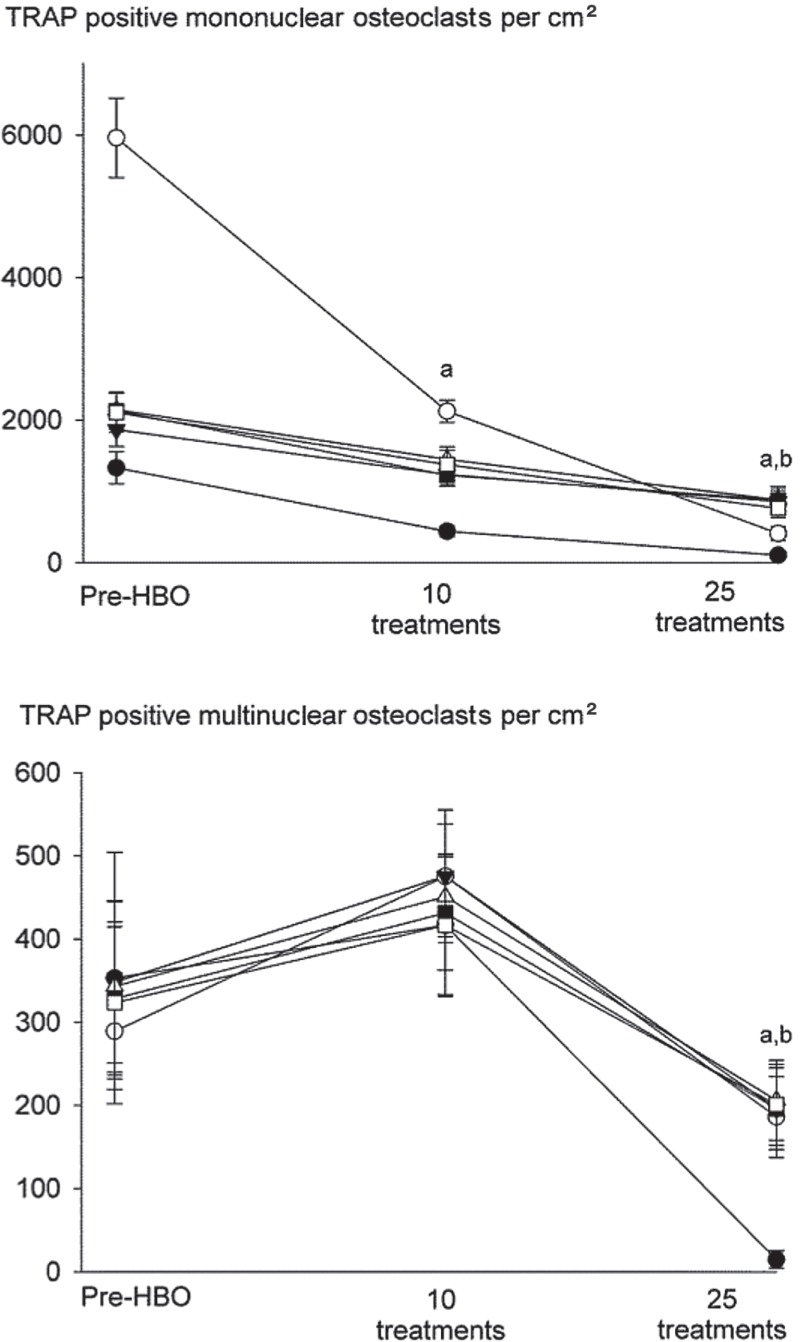

Differences were noted between the effects of HBO on monocular and multinuclear osteoclast formation, with mononuclear osteoclasts showing a more sensitive response than multinuclear cells (Figure 3). RANKL induced a 5-fold increase in the number of mononuclear osteoclasts compared to M-CSF treated basal controls (data not shown). 10 HBO sessions for 90 min a day reduced the number of RANKL-induced TRAP-positive osteoclasts that formed, causing a 50% decrease in numbers of mononuclear osteoclasts compared to pre-HBO. In contrast, no decrease in the numbers of multinuclear cells was noted at this time point. TRAP-positive mononuclear and multinuclear cell numbers were, however, suppressed after 25 HBO sessions, causing an 80% decrease compared to pre-HBO, and returning the numbers to control levels.

Figure 3.

Mononuclear osteoclasts are more sensitive to the inhibitory effect of HBO than multinuclear osteoclasts. Human PBMCs were obtained from patients undergoing HBO and treated with RANKL (30 ng/mL) and M-CSF (50 ng/mL) for 12 days before staining for TRAP. The numbers of mononuclear osteoclasts (with 1–2 nuclei) and multinuclear osteoclasts (with ≥ 3 nuclei) were quantified. Basal control cultures consisted of human PBMCs incubated in M-CSF (50 ng/mL) alone. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 6). a p < 0.05 relative to pre-HBO.

Effect of HBO augments the expression of genes regulating osteoclast formation

To identify possible molecular mechanisms for the action of HBO on the initial stages of monocyte differentiation and multinuclear osteoclast formation, the expression of RANK mRNA, Dc-STAMP mRNA, and NFATc1 mRNA was examined (Table). RANK mRNA expression was increased after 10 HBO treatments; there was a 3.5-fold increase compared to the pre-HBO group. Dc-STAMP expression was also elevated after 10 treatments; there was a 2.3-fold increase compared to the pre-HBO treatment group. However, there was a decrease in RANK and Dc-STAMP mRNA expression after 25 treatments—to 50% (RANK mRNA) and 11% (Dc-STAMP mRNA) of pre-HBO levels. In contrast, HBO had a less pronounced effect on NFATc1 expression. 10 treatments reduced NFATc1 mRNA expression by 30% compared to pre-HBO, but no effect was noted after 25 treatments (Table).

Short-term HBO promotes RANK and Dc-STAMP mRNA expression in osteoclasts derived from human peripheral blood monocytes, while long-term HBO suppresses it. Values are expressed as RQ relative to pre-HBO using the ΔΔCT methodology. For all groups, expression has been normalized to that of β-actin. Values are mean (SEM); n = 6

| RANK RQ (SEM) | Dc-STAMP RQ (SEM) | NFATc1 RQ (SEM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-HBO | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 10 treatments | 3.52 (1.06) a | 2.33 (0.80) a | 0.70 (0.50) |

| 25 treatments | 0.50 (0.39) a | 0.11 (0.05) a | 1.14 (0.30) |

p < 0.05 relative to pre-HBO.

Discussion

PBMCs of patients undergoing HBO become increasingly resistant to RANKL-induced osteoclast formation. As PBMCs are exposed to HBO in vivo prior to RANKL stimulation ex vivo, this suggests that HBO must influence lineage switching—reducing the pool of uncommitted monocytic precursors capable of responding to osteoclast-inductive stimuli. Monocytic precursors are pluripotent, with the potential to differentiate into macrophages, dendritic cells, and osteoclasts. The cell type that a monocyte forms is dependent on the coordinated expression of receptors and key regulatory cytokines. This plasticity enables a cellular response to pathogenic or environmental challenge that results in an optimal number of mature cell types.

Monocytes can be considered to be an increasingly polarized lineage with varying responses to stimulation, rather than a homogenous pool with unlimited differentiation potential. Distinct populations have been isolated from bone marrow and peripheral blood that differentially express surface markers such as CD11b, CD115, and CD117. These populations show separate responses to cytokine stimulation, and as a consequence, distinct abilities to form mature cell types (Jacquin et al. 2006, Jacome-Galarza et al. 2013). It is likely that these populations also differ in their response to other stimuli, such as oxygen levels and HBO. This is supported by the contrasting effect of early-stage HBO treatment on mononuclear and multinuclear osteoclast formation, suggesting that the response varies according to the stage of precursor development—with monocytes further along the osteoclastic lineage being more resistant to the anti-osteoclastic effect of HBO than less committed cells. Thus, the relative lack of effect of HBO on multinuclear osteoclast formation during initial exposure may be due to the presence of osteoclast-committed precursors that are able to fuse to form multinuclear osteoclasts. In contrast, more immature HBO-sensitive precursors become resistant to the effects of RANKL during initial exposure, which rapidly reduces the pool of cells that are able to form mononuclear osteoclasts. As multinuclear osteoclasts develop from mononuclear cells, this will in turn eventually decrease the number of multinuclear osteoclasts. This is supported by the lack of reduction in Dc-STAMP mRNA expression at 10 days; Dc-STAMP is expressed on mononuclear osteoclasts to facilitate fusion and multinuclear osteoclast development. The subsequent fall in Dc-STAMP mRNA expression correlates with a decrease in multinuclear cell number, providing further weight to this assertion. In future, this could be examined further by determining the response of precursors incubated for different periods in RANKL prior to the application of HBO. In addition, while suppressing osteoclast formation, HBO will also provide a larger number of monocytes able to form macrophages—and thus, in conjunction with its modulatory effect on macrophage cytokine production, could augment immune responses (van den Blink et al. 2002). The data also have implications for treatment regimens, as it is unclear whether the suppressive effect would be present if only 10 sessions were administered or whether the complete course is needed for the full anti-osteoclastic effect to be apparent. This is of some importance, as a shorter but equally effective treatment regime would greatly reduce financial costs and issues of patient compliance, although other factors such as the angiogenic potential of HBO must also be considered.

It is not possible to define what aspect of HBO, either elevated oxygen or pressure, induces resistance to RANKL. There is little data on the effect of pressure alone on monocyte function in vivo, although we have previously demonstrated direct effects of pressure on PBMCs in vitro (Al Hadi et al. 2013). The effect of oxygen on monocyte activity is well established, however, as partial pressures vary greatly between marrow, blood, and peripheral tissues—requiring that monocytes should be able to adapt in a timely and appropriate manner. Thus, it is not surprising that changes in oxygen partial pressure evoke rapid changes in monocyte protein expression and function (Reale et al. 2003). From the data, it is clear that one way that HBO induces resistance to RANKL-induced osteoclast formation is by modifying RANK expression. 25 HBO sessions caused a decrease in RANK expression, similar to that seen in vitro (Al Hadi et al. 2013). However the in vivo response to HBO is not as straightforward as that noted in vitro, as 10 exposures increased RANK expression. This suggests that in vivo, the response of monocytes may depend on their stage of differentiation, with newly formed or less mature precursors showing a decrease in RANK but more mature precursors responding with increased expression. This concept is again supported by changes in multinuclear osteoclast formation and Dc-STAMP expression. As Dc-STAMP is a marker of late-stage osteoclast formation and enables fusion of mononuclear cells, this suggests that in vivo, HBO in the short term may possibly accelerate the development of osteoclasts by facilitating the response to RANKL. Alternatively, HBO could suppress osteoclast formation by modifying osteoclast-inductive cytokine expression. HBO has been shown to suppress pro-osteoclastic inflammatory cytokine production while potentiating the expression of inhibitory anti-inflammatory cytokines. For instance, HBO attenuates TNF-α and IL-1 production in animal models of systemic inflammation (Benson et al. 2003), and increases expression of the anti-osteoclastic cytokine IL-10 by T cells (Kudchodkar et al. 2008). Promotion of an anti-osteoclastic cytokine environment has previously been shown to commit precursors to macrophage lineages rather than to osteoclasts, and could at least in part mediate the reduction in osteoclast numbers noted in the current study (Fox et al. 2000).

Our findings suggest that HBO suppresses osteoclast formation and bone resorption from circulating monocytes. This appears to be due to an action on early stages of precursor development and is associated with appropriate changes in the expression of osteoclast genes.

Acknowledgments

HH: study design, collection and interpretation of data, statistics, and drafting of the manuscript. GS: study design and revision of the manuscript. SF: study design, interpretation of data, statistics, and drafting and revision of the manuscript.

This study was funded by the Iraqi government and the Diving Diseases Research Centre.

References

- Al Hadi H, Smerdon GR, Fox SW. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy suppresses osteoclast formation and bone resorption . J Orthop Res. 2013;31(11):1839–44. doi: 10.1002/jor.22443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett TR, Gibbons DC, Utting JC, Orriss IR, Hoebertz A, Rosendaal M, et al. Hypoxia is a major stimulator of osteoclast formation and bone resorption . J Cell Physiol. 2003;196(1):2–8. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson RM, Minter LM, Osborne BA, Granowitz EV. Hyperbaric oxygen inhibits stimulus-induced proinflammatory cytokine synthesis by human blood-derived monocyte-macrophages . Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;134:57–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstone MS. Histochemical demonstration of acid phosphatases with naphthol AS-phosphates . J Natl Cancer I. 1958;21:523–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SW, Fuller K, Bayley KE, Lean JM, Chambers TJ. TGF-ß1 and IFN-g direct macrophage activation by TNF-a to osteoclastic or cytocidal phenotype . J Immunol. 2000;165(9):4957–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.4957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller K, Murphy C, Kirstein B, Fox SW, Chambers TJ. TNFa potently activates osteoclasts, through a direct action independent of and strongly synergistic with RANKL . Endocrinology. 2002;143(3):1108–18. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.3.8701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill AL, Bell C NA. Hyperbaric oxygen: its uses, mechanisms of action and outcomes . Q J Med. 2004;97(7):385–95. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hch074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman RJ. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for wound healing and limb salvage: A systematic review . PM&R. 2009;1(5):471–89. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacome-Galarza CE, Lee SK, Lorenzo JA, Aguila HL. Identification, characterization, and isolation of a common progenitor for osteoclasts, macrophages, and dendritic cells from murine bone marrow and periphery . J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(5):1203–13. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquin C, Gran DE, Lee SK, Lorenzo JA, Aguila HL. Identification of multiple osteoclast precursor populations in murine bone marrow . J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(1):67–77. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudchodkar B, Jones H, Simecka J, Dory L. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment attenuates the pro-inflammatory and immune responses in apolipoprotein E knockout mice . Clin Immunol. 2008;128(3):435–41. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhonen A, Haaparanta M, Grönroos T, Bergman J, Knuuti J, Hinkka S, et al. Osteoblastic activity and neoangiogenesis in distracted bone of irradiated rabbit mandible with or without hyperbaric oxygen treatment . Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33(2):173–8. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2003.0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquier D, Hoelscher T, Schmutz J, Dische S, Mathieu D, Baumann M, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of radio-induced lesions in normal tissues: a literature review . Radiother Oncol. 2004;72(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitak-Arnnop P, Sader R, Dhanuthai K, Masaratana P, Bertolus C, Chaine A, et al. Management of osteoradionecrosis of the jaws: An analysis of evidence . Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:1123–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reale M, Di Giulio C, Cacchio M, Barbacane RC, Grilli A, Felaco M, et al. Oxygen supply modulates MCP-1 release in monocytes from young and aged rats: decrease of MCP-1 transcription and translation is age-related . Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;248(1)(2):1–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1024154704469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibbles PM, Edelsberg JS. Hyperbaric-oxygen therapy . N Engl J Med. 1996;334(25):1642–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606203342506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utting JC, Robins SP, Brandao-Burch A, Orriss IR, Behar J, Arnett TR. Hypoxia inhibits the growth, differentiation and bone-forming capacity of rat osteoblasts . Exp Cell Res. 2006;312(10):1693–702. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Blink B, van der Kleij AJ, Versteeg HH, Peppelenbosch MP. Immunomodulatory effect of oxygen and pressure. Comparative biochemistry and physiology Part A. Mol Integr Phys. 2002;132:1, 193–7. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Malda J, Crawford R, Xiao Y. Effects of hyperbaric oxygen on proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts from human alveolar bone . Conn Tiss Res. 2007;48:206–13. doi: 10.1080/03008200701458749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]