Abstract

Adoptive cell therapy (ACT) for cancers using autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) can induce immune responses and antitumor activity in metastatic melanoma patients. Here, we aimed to assess the safety and antitumor activity of ACT using expanded TILs following concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). Twenty-three newly diagnosed, locoregionally advanced NPC patients were enrolled, of whom 20 received a single-dose of TIL infusion following CCRT. All treated patients were assessed for toxicity, survival and clinical and immunologic responses. Correlations between immunological responses and treatment effectiveness were further studied. Only mild adverse events (AEs), including Grade 3 neutropenia (1/23, 5%) consistent with immune-related causes, were observed. Nineteen of 20 patients exhibited an objective antitumor response, and 18 patients displayed disease-free survival longer than 12 mo after ACT. A measurable plasma Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) load was detected in 14 patients at diagnosis, but a measurable EBV load was not found in patients after one week of ACT, and the plasma EBV load remained undetectable in 17 patients at 6 mo after ACT. Expansion and persistence of T cells specific for EBV antigens in peripheral blood following TIL therapy were observed in 13 patients. The apparent positive correlation between tumor regression and the expansion of T cells specific for EBV was further investigated in four patients. This study shows that NPC patients can tolerate ACT with TILs following CCRT and that this treatment results in sustained antitumor activity and anti-EBV immune responses. A larger phase II trial is in progress.

Keywords: adoptive cell therapy, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

Abbreviations: ACT, adoptive cell therapy; CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy; CR, complete response; DFS, disease-free survival, EBNA1; Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen 1; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; EBV-CTLs, EBV-specific cytotoxic T cells; ELISPOT, enzyme-linked immunospot; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; GMP, good manufacturing practices; LMP1, latent membrane protein-1; LMP2, latent membrane protein-2; NPC, nasopharyngeal carcinoma; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; PR, partial response; PD, progressive disease; REP, rapid expansion protocol; SFCs, spot-forming cells; TILs, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

Introduction

NPC arises in the epithelial cells of the nasopharynx at a high frequency in Southest Asia and Southern China, whereas it shows a low frequency worldwide.1,2 Compared to the favorable prognosis of NPC patients at the early disease stage,3 the incidence of treatment failure is still high in locoregionally advanced NPC.4 Although CCRT can improve the treatment outcomes of these patients, approximately 25% of locoregionally advanced NPCs display failure after receiving CCRT treatment.5-7 Furthermore, Ma et al. reported that adjuvant chemotherapy in addition to CCRT did not significantly improve patient survival compared to CCRT alone in locoregionally advanced NPC patients and that patient compliance was unsatisfactory due to serious toxicity.8 Hence, there is an urgent need for novel strategies to improve disease-free survival and reduce treatment-related toxicity in patients.

In South China, 95% of NPCs are undifferentiated carcinomas (WHO type III) associated with EBV infection.9 The consistent presence of EBV in NPC cells provides the possibility of an immunotherapeutic approach that exploits the potential of T cells to recognize tumor cells through the expression of viral antigens.10-12 The phase I and phase II studies conducted to date involving the adoptive transfer of autologous EBV-specific cytotoxic T cells (EBV-CTLs) have proved safe and potentially effective against EBV-associated malignancies, including NPC.13-19 However, differences in the EBV antigens presented between tumor cells and EBV-transformed B cells (from cell line B95.8) as well as the laboratory work required to generate EBV-CTLs have limited the clinical benefits and applications of EBV-CTL immunotherapy for NPC patients.20-22

Accumulating evidence shows that TILs selected for tumor recognition and greatly expanded in vitro are especially effective for treating cancer patients, but the success of current approaches is primarily limited to patients with melanoma, and we are still far from offering such treatment to the majority of patients.23-27 To our knowledge, this is the first phase I clinical trial study involving combination treatment with CCRT and adaptive cell transfer (ACT) using ex vivo rapidly expanded autologous TILs as a novel strategy in locoregionally advanced NPC patients. The data presented here show that infusion of autologous TILs was well tolerated, induced an EBV antigen-specific immune response and reduced the plasma EBV load in vivo. In addition, the clinical objective response, defined as a complete response (CR), was observed in 19 of 20 enrolled patients (95%) who received ACT following CCRT treatment, and a correlation between tumor regression and an EBV-specific immune response was observed in some patients.

Results

Patient characteristics

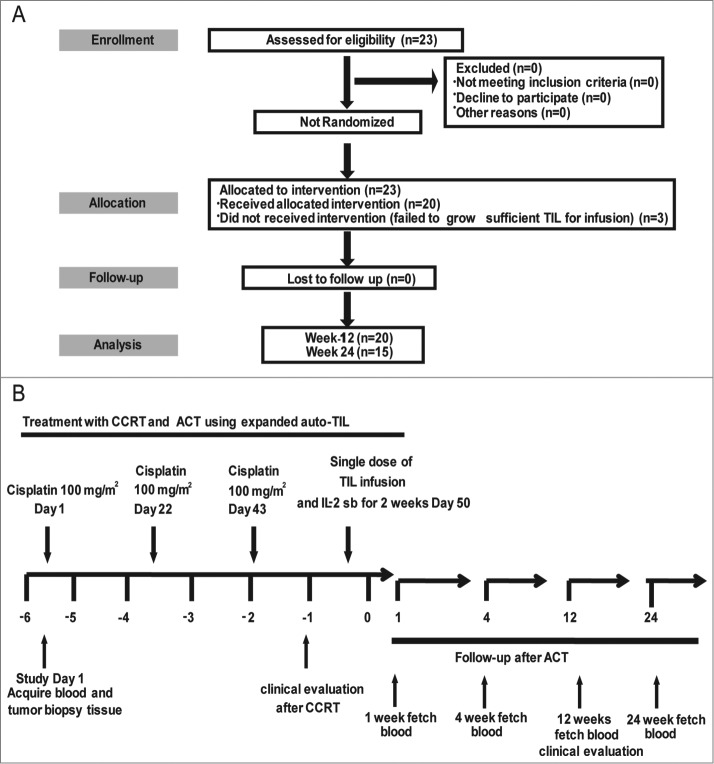

Twenty-three patients were enrolled in this study, and all patients presented undifferentiated NPC (WHO III) at an advanced stage (stage III–IV) without distant organ metastasis at diagnosis. Among these 23 patients, 18 were male and 5 were female, and the median age was 45.5 y (range, 29–62 y). Three patients who failed to produce sufficient TILs did not undergo further TIL infusion, and therefore, 20 patients received TIL infusion following CCRT. The detailed clinical characteristics and treatments administered to the patients are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1. In addition, detailed information about the expression of EBV antigens (LMP1, LMP2, and EBNA1) in NPC cells, the number of leukocytes, the plasma EBV load, the titer of EBV antibodies and the IFNγ levels found in the patients at the time of diagnosis are shown in Table S1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics, cell numbers and clinical responses (n = 23)

| Response to therapy | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient No. | Age/Gender | TNM/stage | Site of active disease at enrollment | Treatment prior to infusion (CCRT) | Infused cells (X109) | Objective response | PFS (Month) | Tumor residual or relapse or metastasis |

| 1 | 46/M | T3N1M0/III | 1, 2, 4 | CT×3,RT | Failed | CR | 26 | No |

| 2 | 46/M | T2N2M0/III | 1, 5 | CT×2,RT | Failed | CR | 25 | No |

| 3 | 45/M | T3N2M0/III | 1, 2, 5 | CT×3,RT | 1.6 | PR, 3 months later CR | 25 | No |

| 4 | 48/F | T3N1M0/III | 1, 2, 4 | CT×3,RT | 1.8 | PR, 3 months later CR | 23 | No |

| 5 | 53/M | T3N1M0/III | 1, 2, 4 | CT×3,RT | 6.3 | CR | 22 | No |

| 6 | 37/M | T3N2M0/III | 1, 2, 5 | CT×3,RT | 5.2 | CR | 21 | No |

| 7 | 59/M | T3N2M0/III | 1, 2, 5 | CT×3,RT | 1.8 | CR | 20 | No |

| 8 | 45/M | T3N2M0/III | 1, 2, 5 | CT×3,RT | 2.1 | PR, 3 months later CR | 20 | No |

| 9 | 56/F | T3N0M0/III | 1, 2 | CT×3,RT | 2.4 | CR, 6 months later relapse | 11 | Relapse in nasopharynx, received endoscopic nasopharyngectomy |

| 10 | 28/F | T3N1M0/III | 1, 2, 4 | CT×3,RT | 3.1 | PR, 7 months later PD | 12 | Residual in neck, received selective neck dissection |

| 11 | 62/M | T3N3M0/IV | 1, 2, 5, 6 | CT×3,RT | 2.3 | PR, 3 months later CR | 18 | No |

| 12 | 37/M | T4N3M0/IV | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 | CT×3,RT | 4.6 | PR, 3 months later CR | 17 | No |

| 13 | 54/F | T3N1M0/III | 1, 2, 4 | CT×3,RT | 2.6 | PR, 3 months later CR | 18 | No |

| 14 | 54/M | T4N2M0/IV | 1, 2, 3, 5 | CT×2,RT | 1.3 | CR | 17 | No |

| 15 | 40/M | T3N2M0/III | 1, 2, 5 | CT×3,RT | 4.5 | CR | 15 | No |

| 16 | 40/F | T2N2M0/III | 1, 5 | CT×3,RT | Failed | CR | 14 | No |

| 17 | 55/M | T3N2M0/III | 1, 2, 5 | CT×3,RT | 1.8 | CR | 14 | No |

| 18 | 30/F | T2N3M0/IV | 1, 5, 6 | CT×3,RT | 2.4 | CR | 14 | No |

| 19 | 29/M | T2N2M0/III | 1, 5 | CT×3,RT | 1.9 | CR | 12 | No |

| 20 | 54/F | T4N1M0/IV | 1, 2, 3, 4 | CT×3,RT | 2.5 | CR | 12 | No |

| 21 | 41/M | T4N1M0/IV | 1, 2, 3, 4 | CT×3,RT | 2.3 | CR | 12 | No |

| 22 | 48/M | T3N1M0/III | 1, 2, 4 | CT×2,RT | 3.1 | CR | 12 | No |

| 23 | 38/M | T4N1M0/IV | 1, 2, 3, 4 | CT×2,RT | 4.1 | CR | 12 | No |

Note: 1 = nasopharynx; 2 = skull bone; 3 = cavernous sinus; 4 = unilateral upper cervical lymph node; 5 = double upper cervical lymph node; 6 = lower cervical lymph node; CCRT = concurrent chemoradiotherapy; CT = chemotherapy; RT = radiotherapy; CR = complete response; PR = partial response; PD = progressive disease

Figure 1.

Clinical trial scheme and protocol. (A) Consort diagram. (B) Study timelines depicting CCRT (radiotherapy (70 Gy) + chemotherapy (cisplatin 100 mg/m2 × 3, at day 1, 22, and 43)) treatment, TIL infusion (one week after CCRT) and PBMC sampling for immune monitoring. PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; CCRT, concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

TIL expansion and adoptive cell therapy

Approximately 23 cultures were initiated from each patient, and 20 of these gave rise to a culture showing sufficient growth for further expansion. REP was begun at an average cell count of 16 × 106 (range 11–20 × 106) cells after 15 d of culture. On average, 2.6 × 109 (range 1.3 – 6.3 × 109) TILs were infused into each patient (Table 1) one week after CCRT. The phenotypes of the infused TILs were analyzed via FACS array (Table S2). The results were similar to those presented in our previous report on a pre-clinical stage study.28

Safety and clinical evaluation

The most common toxicities arising from CCRT and ACT recorded during the study are listed in Table 2. During CCRT treatment, the majority of AEs were of grade 1 or 2. However, 7 patients (30.4%) presented grade 3 or grade 4 radiation mucositis, and 4 patients (17.4%) displayed grade 3 or grade 4 radiation dermatitis. One patient (4.3%) exhibited grade 3 vomiting. In the case of hematologic toxicity, 3 patients (13%), 1 patient (4.3%) and 6 patients (26%) presented grade 3 leukopenia, neutropenia, and lymphocytopenia, respectively. During ACT treatment, no infections, fever or allergic reactions were observed following TIL infusion. Only 3 patients (15%) showed grade 1 or grade 2 mucositis, 1 patient (5%) exhibited grade 2 vomiting, and 1 patient (5%) presented grade 3 leucopenia and neutropenia.

Table 2.

Toxicities in patients in response to chemoradiotherapy and adoptive cell therapy (n = 23)

| Chemoradiotherapy* | Adoptive cell therapy | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 0 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 0 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |

| Fatigue | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Leukopenia | 9 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 17 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 15 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Lymphocytopenia | 8 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anemia | 13 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Thrombopenia | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 4 | 13 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 4 | 13 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Infections | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Alopecia | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dermatitis | 3 | 9 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mucositis | 0 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 3 | 17 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Allergic reaction | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Low sodium levels | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

*: chemoradiotherapy = radiotherapy (70 Gy) + chemotherapy (cisplatin 100 mg/m2× 3)

Of the 23 enrolled patients, 16 (69.5%) achieved a CR at the completion of CCRT; 19 (83%) achieved a CR 3 mo after the completion of ACT; and 18 exhibited disease-free survival (DFS) for longer than 12 mo. Only one patient (P9) presented a residual neck lymph node 3 mo after ACT and subsequently underwent selective neck dissection. One patient (P10) showed recurrence in the nasopharynx 6 mo after ACT and successfully underwent endoscopic nasopharyngectomy. The detailed clinical responses of the patients are shown in Table 1.

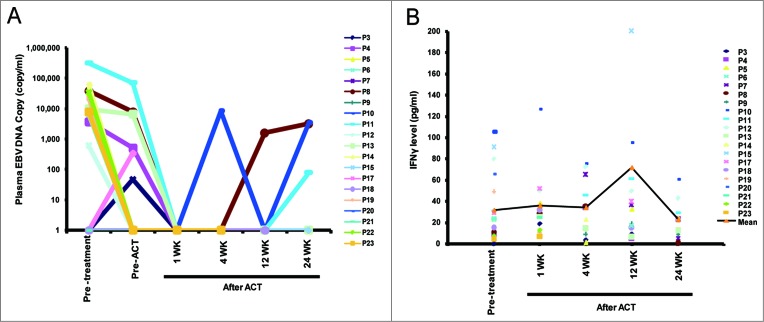

Analysis of plasma EBV viral loads and IFNγ secretion

Plasma EBV DNA is a marker of disease progression in NPC patients.29,30 In this study, 14 of the 23 (65.2%) enrolled patients receiving ACT treatment exhibited a high EBV DNA load (mean = 3.4 × 104 copies) at the time of diagnosis (Table S1). Six of the 23 patients still displayed a detectable EBV DNA load following the completion of CCRT treatment (mean = 1.6 × 104 copies), and the EBV DNA load was increased in 2 (P3 and P17) of the 6 EBV DNA-positive patients at the completion of CCRT treatment compared with at diagnosis. However, the EBV DNA load was undetectable in all patients, including the 6 EBV DNA load-positive cases, after one week of TIL infusion. Furthermore, the EBV DNA load was detectable in one patient (P10, 8.7 × 103 copy) and in three patients (P8, P10, and P23; mean = 3.0 × 103 copies) at 1 and 6 mo after TIL infusion, respectively (Fig. 2A and Table S3). Furthermore, the plasma IFNγ level was slightly increased at 1 week, 4 weeks, and 12 weeks, and it decreased at 24 weeks after TIL infusion compared to diagnosis (p > 0.05, Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Changes in the plasma EBV load and IFNγ level in enrolled patients. (A) The plasma EBV DNA copy number in patients (n = 20) was detected via real-time PCR at different time points before and after TIL infusion. (B) The plasma IFNγ level was determined via ELISA (n = 20). ATC, adoptive cell therapy; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus.

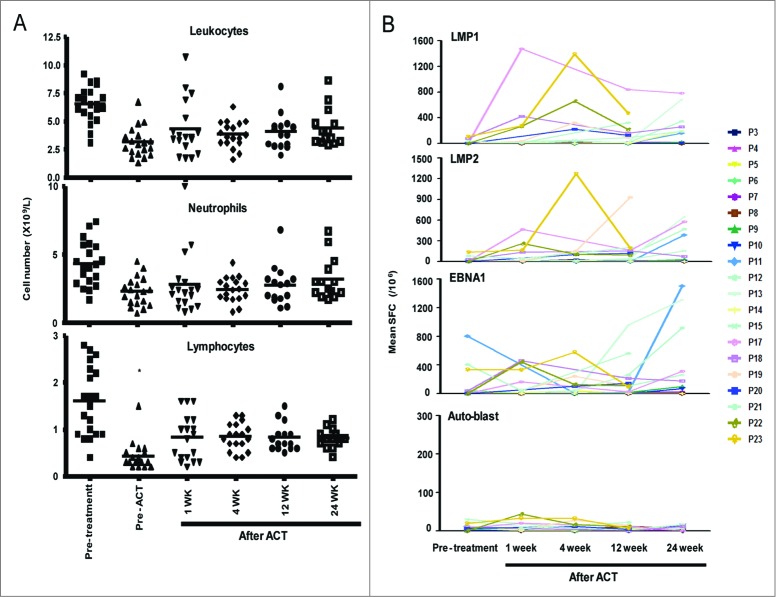

Expansion and persistence of EBV antigen-specific T cells

One of the key problems that may limit tumor regression and long-term durable clinical responses under ACT is the persistence of TILs following infusion.31 In the present study, the applied CCRT treatment greatly decreased the number of total leukocytes that were present, including neutrophils and lymphocytes, prior to ACT in all patients. The number of lymphocytes significantly increased after one week of TIL infusion, and this value reached the normal range within 6 mo after TIL infusion. In contrast, the numbers of leukocytes and neutrophils were only slightly increased (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Increases in lymphocytes and T cells specific for EBV antigens following TIL infusion. (A) The number of leukocytes, neutrophils and lymphocytes at different times before and after TIL infusion (n = 20). (B) The mean number of SFCs in T cells specific for the EBV antigens LMP1, LMP2, and EBNA1 in 106 PBMCs from patients at 1 week or 1, 3 or 6 months after TIL infusion compared to at the time of diagnosis (n = 20). Student's t test was used. * indicates p < 0.05. Auto-blast, autologous PHA-stimulated blast cells; EBNA1, Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen 1; LMP1, latent membrane protein-1; LMP2, latent membrane protein-2; SFC, spot-forming cells.

The expansion of the T-cell population specific for EBV antigens was assessed in vivo via IFNγ ELISPOT assays using a peptide pool of LMP1, LMP2 or EBNA1 as a stimulator of PBMCs at multiple time points before and after ACT. The baseline frequency of EBV antigen-specific T cells was very low at the time of diagnosis, as measured by ELISPOT assays. Following TIL infusion, the expansion of EBV antigen (LMP1, LMP2, or EBNA1)-specific T cells in PBMCs was observed in 13 of the 20 patients (65%; > fold10-, Fig. 3B and Fig. S1), and the increase in T cells specific for EBV antigens persisted for 6 mo after TIL infusion. However, no expansion of T cells against EBV-negative auto-blast cells in PBMCs was observed.

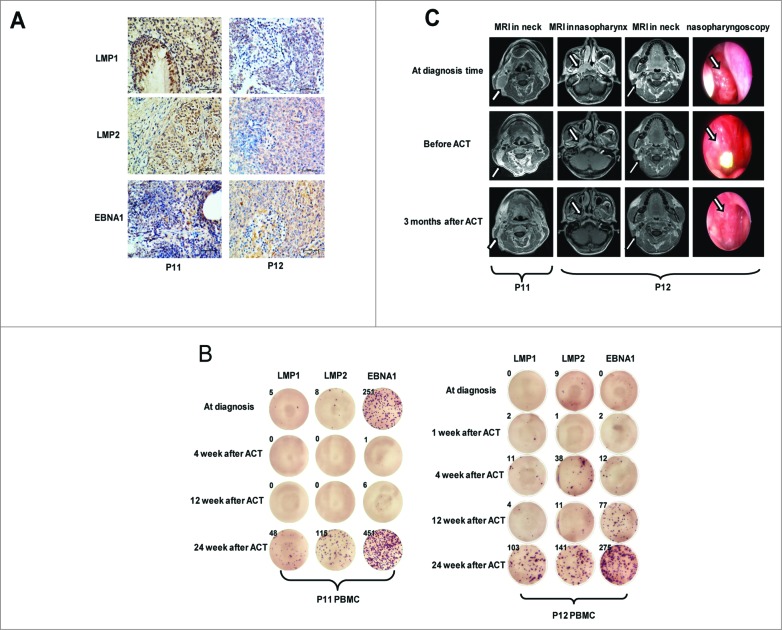

Correlation between anti-EBV immunity and clinical evolution

To address the correlations between the observed clinical responses and the expansion of the T cell population specific for EBV antigens in vivo, we assessed the status of EBV antigen-specific T cells before and after TIL infusion in the treated patients with a distinctive clinical response. Patients P11 (T3N3M0/stage IV) and P12 (T4N3M0/stage IV) had larger tumors and lymph nodes and exhibited high expression of LMP1, LMP2, and EBNA1 in NPC tissues (Fig. 4A) and a high plasma EBV load (3.18 × 105 and 6.08 × 102 copies) at the time of diagnosis (Table S1). These patients also showed great expansion of LMP1 antigen-specific T cells (>200 fold, Fig. S1), high persistence of LMP2 and EBNA1 antigen-specific T cells (P11) and stronger expansion of T cells specific for LMP1 and EBNA1 antigens (>200 fold) in vivo (P12) up to 6 mo after TIL infusion (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, these patients (P11 and P12) displayed a partial response (PR) after CCRT but achieved a CR 3 months after ACT, with a reduction in lymphoid nodes in the neck (P11) as well as a decreased tumor load in the nasopharynx and a reduction of lymphoid nodes in the neck (P12), as detected by MRI (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, all of the remaining 11 patients who had apparent expansion of EBV antigen-specific T cells after TIL infusion (65%; >10 fold, Fig. 3B and Fig. S1) achieved a CR 3 mo after ACT treatment and maintained DFS for longer than 12 mo. In contrast, the other two patients (P9 and P10), who showed tumor relapse or progressive disease (PD), exhibited poor anti-EBV immune responses following TIL infusion (Table 1 and Fig. S2). P9 (T3N0M0/stage III) presented a CR after ACT but had a relapse in the nasopharynx and accepted endoscopic nasopharyngectomy 6 mo after ACT. P10 (T3N1M0/III) exhibited tumor residue in the neck, only showed a PR following ACT and presented a PD and accepted selective neck dissection 7 mo after ACT; furthermore, the plasma EBV load in P10 became positive within 1–6 mo after ACT. No statistical correlation between anti-EBV immunity and clinical evaluation was found in this phase I study due to the small set data; however, a positive correlation between clinical benefits and anti-EBV immune responses was observed in some patients.

Figure 4.

Correlations between tumor markers, characteristics of TIL production, expansion of EBV antigen-specific T cells and NPC tumor regression following ACT. (A) The expression of EBV antigens, including LMP1, LMP2, and EBNA1, in tumor cells of NPC tissues (P11 and P12) was measured via immunohistochemical staining. (B) The number of IFNγ spot-forming cells (SFCs) per 3 × 105 PBMCs from P11 and P12 at multiple times after stimulation by LMP1, LMP2, and EBNA1 pooled peptides in vitro was captured using the CTL image system and counted using ImmunoSpot 5.1.34. (C) MRI and nasopharyngoscopy images of NPC tumor lesions in the nasopharynx and neck at the time of diagnosis, pre-ACT and 3 weeks after ACT in P11 and P12. ATC, adoptive cell therapy; CTL, cytotoxic T cell; EBNA1, Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen 1; LMP1, latent membrane protein-1; LMP2, latent membrane protein-2; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the safety, clinical activity and immunologic correlates of the responses of locoregionally advanced NPC patients who underwent CCRT and ACT using autologous ex vivo-expanded TILs. First, we successfully acquired sufficient TILs for ACT from 20/23 enrolled, locoregionally advanced NPC patients (87%) at their initial diagnosis (Table 1). Immunotherapy using autologous TILs has emerged as a powerful treatment option for patients with metastatic melanoma.32,33 However, due to the technical barrier of obtaining too few therapeutic TILs from NPC tumor tissues for clinical use, in recent years, adoptive autologous T-cell immunotherapy in NPC patients has been limited to using EBV antigen-responsive T cells from the PBMCs of patients, including EBV-CTLs, AdE1-LMPpoly-generated T cells and T cells transduced with the EBV antigen-specific TCR gene.14,20,22,34-36 This study represents the first clinical trial to perform ACT using autologous expanded TILs in NPC patients. A distinct advantage of TIL therapy is the broad nature of the T-cell recognition of both defined and undefined tumor antigens against all possible major histocompatibility complexes, in contrast to the single specificity and limited major histocompatibility complex coverage of the newer T cell receptor and chimeric antigen receptor transduction technologies.31,37 Therefore, in this study, the TILs obtained following ex vivo REP expansion contained a high frequency of tumor associated-viral antigen-specific T cells, including EBV LMP1-, LMP2-, and EBNA1-specific T cells with immunological activity. The advantage of performing ACT using TILs in NPC patients was that the TILs included a high frequency of EBV antigen-specific T cells, which can home to tumor tissues of patients and can vary with the tumor associated-viral antigens in each patient.

In our study, the short-term CR was 69.5% in the 23 enrolled patients at the completion of CCRT and 83% (19/23, DFS >9 ) at 3 mo after ACT when using auto-TILs (Table 1). Additionally, the plasma EBV load in the enrolled patients was dramatically decreased after one week of ACT and remained below the measurable level in most patients after 6 mo of ACT (17/20, Fig. 2). These results strongly suggest that this new strategy results in sustained clinical responses in locoregionally advanced NPC patients. In addition, the good tolerance of ACT using TILs accompanied by IL-2 injection following CCRT in NPC patients was indicated by the absence of treatment-related deaths, infections, fever and allergic reactions (Table 2), in line with previous reports for TIL infusion accompanying IL-2 injection treatment in metastatic melanoma.23,38,39,40,41

Metastatic melanoma patients who are initially treated with TILs and IL-2 without lymphodepletion display a response rate of 39%. A subsequent series of seminal phase II clinical trials in melanoma patients utilized a preparative lymphodepleting chemotherapy regimen prior to infusion with TILs and IL-2, resulting in an unprecedented 50% response rate.42 However, in NPC immunotherapy, higher doses of EBV-specific CTLs following lymphodepleting chemotherapy consisting of fludarabine and cyclophosphamide do not provide additional benefits or show competing effects compared to EBV-specific CTL administration.43 Hence, we performed ACT using TILs, followed by CCRT treatment in locoregionally advanced NPC patients, and no lymphoablative chemotherapy was included in this approach. Our results show that the CCRT treatment conducted prior to TIL-transferred ACT decreased the tumor burden and immune cell numbers, including those of leukocytes, neutrophils and lymphocytes (Fig. 3), and expansion of T cells specific for EBV antigens was observed in 13 of 20 patients after TIL infusion (65%; > fold10-, Fig. 3 and Fig. S1). These results indicate that ACT treatment induced anti-EBV immune responses in patients and that this CCRT treatment applied prior to TIL transfer also decreased the number of lymphocytes, thus enhancing antigen-specific T-cell expansion in vivo.

The correlation between the immune response and clinical benefits has been reported in TIL therapy for melanoma.44,45 Here, we also found a positive correlation between the expansion of T cells specific for EBV antigens and tumor regression in some patients with or without apparent clinical responses (P11, P12, P9, and P10) (Fig. 4 and Fig. S2). However, we failed to find a statistical correlation between the clinical benefit and the frequency or expansion of EBV antigen-specific T cells that were measured in the peripheral blood of the treated patients at this small-scale, phase I study. Therefore, it is important to perform a large-scale, randomized phase II study to define the correlation between the clinical benefit and efficacy of TIL immunotherapy. In addition, it is important to mention the key role of EBNA1 antigens, which were expressed on the NPC cells of most patients (Table S1), in TIL therapy for NPC patients. EBNA1 proteins only present antigens for the Ala–Gly repeat sequence to CD4+ lymphocytes.46 The TILs from NPC patients had a high frequency of CD4+ T cells and always developed a high frequency of CD4+IFNγ-releasing cells in response to EBNA1 stimulation, which could induce the expansion of EBNA1-specific T cells in vivo (data not shown) and could contribute to tumor regression, as shown in clinical evaluations. Based on our results, the clinical benefits to patients are not completely dependent on the numbers of TILs and CD8+ T cells, as reported for TIL immunotherapy in melanoma.44

In summary, we showed for the first time that the new strategy for infusion of ex vivo-expanded TILs following CCRT was well tolerated and caused an apparent clinical response and tumor regression in locoregionally advanced NPC patients. The induction of anti-EBV immune responses was investigated during tumor regression in some patients. However, in this phase I study we did not clearly define the outcome and efficacy of TIL immunotherapy. A randomized, phase II study based on these findings will be performed in the near future. These results support further clinical studies of the use of ex vivo-expanded TILs for the treatment of NPC patients.

Patients and Methods

Patients

The patients were evaluated using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 2010 staging system47 and were eligible for this study if they fulfilled all of the following criteria: biopsy-proven World Health Organization (WHO) types II–III NPC; stage III–IVb; age 18–70 y; adequate hematologic, renal and hepatic function; and satisfactory performance status (a score of 0 or 1 using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group System). The exclusion criteria included previous treatment for NPC, the presence of a distant metastasis, prior malignancy, an abnormal blood cell count, other active systemic infections, other active major medical or cardiovascular diseases, immunodeficiencies or positivity for HIV antibodies. All patients signed an informed consent form approved by the Review Board and Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center.

Clinical trial design and evaluation

The phase I trial (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT 01462903) design is shown in Fig. 1. The trial was conducted in accordance with local regulations, with the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, and with the principles of the current version of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients received intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) according to standard departmental protocols. The planning target volumes (PTVs) were expansions of the respective clinical target volume (CTV) with a margin of 3 mm, except when close to critical structures, where smaller margins were acceptable. The PTV of the GTVnx was treated with 70 Gy in 30–32 fractions. The PTVs for CTV-1 and CTV-2 received 60 Gy and 54 Gy in 30–32 fractions, respectively, and 60–66 Gy was applied for the PTV of the nodal gross tumor volume (GTVnd). Cisplatin was administered at 100 mg/m2 on days 1, 22, and 43 of radiotherapy. One week after the completion of CCRT, patients received a single-dose intravenous infusion of TILs (average infused TIL number = 2.6 × 109 ± 2.2) and began a 14-d regimen of low-dose IL-2 subcutaneous injection. The National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 3.0 scale was used to assess toxicity. The tumor response was evaluated through physical examination, nasopharyngoscopy and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck at the completion of CCRT and 3 mo after the completion of RT. The patients were then classified into complete, partial or nonresponders according to the WHO response criteria and/or Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST).

Generation and expansion of TILs ex vivo

Bulk TILs were obtained from biopsied NPC tumors and expanded using a rapid expansion protocol (REP)48 under conditions in accordance with current good manufacturing practices (GMP) in the Biotherapy Center at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. TILs were isolated from NPC biopsy specimens by mincing the tissue into small pieces and digesting them with collagenase type IV (0.1 μg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h, followed by culture in X-VIVO-15 medium (Lonza) containing 5% human AB serum and recombinant human IL-2 (150 IU/mL) in 24-well plates. Once a sufficient number of T cells (>10 × 106) was generated, they were cryopreserved for further expansion. A REP for “young TILs” that was previously used in melanoma patients was followed. Cryopreserved, pre-REP TILs from patients who were to be treated were thawed and further expanded to treatment levels using an anti-CD3 antibody (OKT-3, 30 ng/mL, R&D Systems), rhIL-2 (BD PharMingen) and irradiated feeder cells, as previously described. The immunophenotypes and functions of the bulk TILs were determined via fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and cytotoxic analysis of EBV-positive targets and NPC cells, as reported previously.48

Immunologic monitoring assays

Flow cytometry. All monoclonal antibodies were obtained from BD Biosciences, PharMingen or eBioscience and included anti-CD3, -CD4, -CD8, -CD16, -CD25, -CD27, -CD154, -CD45RA, -CD45RO, -CD62L, -CD137, -CCR7, -HLA-DR, -Foxp3 and -IFNγ. The cells were stained as previously described. In all cases, the negative controls were isotype antibodies. All stained cells were measured using an FC500 flow cytometer, and the obtained data were analyzed with CXP software (Beckman Coulter).

qPCR and ELISA determination of the serum EBV DNA load and IFNγ levels. The EBV DNA copy numbers in patient serum before and at multiple times after TIL infusion were determined via real-time quantitative PCR using the QIAamp Blood Kit (Qiagen) and the probe W-67T, which was derived from the BamHI-W region of the EBV genome. Serum IFNγ levels were measured in patients before and at multiple times after TIL infusion using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and the Human IFNγELISA Ready-SET-Go kit (eBioscience). Briefly, a 96-well plate was coated with 100 μL of coating diluent at 4°C and incubated overnight. Then, 100 μL of a standard or sample was added to the appropriate wells, and the plate was incubated for 2 h at room temperature (RT). The wells were then washed five times with wash buffer, and an anti-IFNγ conjugate was added to all wells, followed by further incubation at RT. The plate was washed another 5–7 times, and 100 μL of Avidin-HRP was added. The plate was then incubated for 30 min at RT, and 100 μL of substrate solution was added to each well after washing again with washing buffer. The plate was subsequently incubated for 15 min at RT in the dark, after which 50 μL of stop solution was added to each well, and the absorption at 450 nm was detected using a 96-well plate reader (Bio-rad).

IFNγ Enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assays. The frequency of EBV LMP1-, LMP2- and EBNA1-specific T cells in the peripheral blood of patients before and at multiple times after TIL infusion and in the infused TIL products was measured using an interferon-γ (IFNγ) ELISPOT assay. The IFNγ ELISPOT assay was performed using a human IFNγ pre-coated ELISpotPRO Kit (DKW22–1000, Da Ke Wei Company), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, pre-coated 96-well plates were washed with sterile PBS and blocked for 10 min with Lympho-SpotTM medium. The blocking medium was then removed, and PBMCs (2 × 105 cells per well) were incubated for 20 h at 37°C with 5 μg/mL of the LMP1, LMP2 and EBNA1 proteins (Miltenyi Biotec Company) or autologous PHA-stimulated blast cells as a control. The plates were washed to remove cells and then incubated with the one-step detection reagent for 1 h at 37°C. ELISPOTs were developed using AEC-plus and counted automatically using ImmunoSpot 5.0.3 analysis software. The ELISPOT results are expressed as the number of spot-forming cells (SFCs) per 106 PBMCs. This assay was conducted in two replicate wells for each sample.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was carried out using primary monoclonal mouse anti-human CD4+ (1/200, DAKO), anti-human CD8+ (1/200, DAKO), anti-EBV LMP1 (1/100 dilution, DAKO), anti-EBV LMP2 (1/100 dilution, gift from Prof. Mu-sheng Zeng) and anti-EBV EBNA1 (1/300 dilution, DAKO) antibodies, as per the manufacturer's instructions. Mouse-anti-human IgG1 (1/200 dilution, DAKO) was used as a negative control. Immunostaining was conducted according to routine automated methods.

Statistical analysis

Standard two-tailed Student's t tests were performed to assess the associations between categorical variables and the immune response. The Mann–Whitney U test was applied to compare continuous variables with the immune response or T cell types. All analyses were carried out using SPSS 13.0 or GraphPad Prism 5 software, with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rong-Fu Wang (Methodist Hospital, Houston, Texas, USA) and Xiao-Feng Qin (Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China) for their help in setting up the TIL technique and for their review of this manuscript.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81372442 and 81172164), the Key Sci-Tech Program of the Guangzhou City Science Foundation (Grant No. 2011Y100036), the 863 Project (Grant No. 2013CB910304), the National Key Basic Research Program of China (Grant No. 2012CB910304), the Sun Yat-sen University Clinical Research 5010 Program and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's website.

References

- 1. Li J, Zeng XH, Mo HY, Rolen U, Gao YF, Zhang XS, Chen QY, Zhang L, Zeng MS, Li MZ, et al. Functional inactivation of EBV-specific T-lymphocytes in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: implications for tumor immunotherapy. PLoS One 2007; 2:e1122; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0001122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cao SM, Simons MJ, Qian CN. The prevalence and prevention of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in China. Chinese J Cancer 2011; 30:114-9; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.5732/cjc.010.10377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dechaphunkul T, Pruegsanusak K, Sangthawan D, Sunpaweravong P. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy with carboplatin followed by carboplatin and 5-fluorouracil in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck Oncol 2011; 3:30; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1758-3284-3-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen MY, Jiang R, Guo L, Zou X, Liu Q, Sun R, Qiu F, Xia ZJ, Huang HQ, Zhang L, et al. Locoregional radiotherapy in patients with distant metastases of nasopharyngeal carcinoma at diagnosis. Chinese J Cancer 2013; 32:604-13; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.5732/cjc.013.10148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huncharek M, Kupelnick B. Combined chemoradiation versus radiation therapy alone in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: results of a meta-analysis of 1,528 patients from six randomized trials. Am J Clin Oncology 2002; 25:219-23; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00000421-200206000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Langendijk JA, Leemans CR, Buter J, Berkhof J, Slotman BJ. The additional value of chemotherapy to radiotherapy in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a meta-analysis of the published literature. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22:4604-12; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baujat B, Audry H, Bourhis J, Chan AT, Onat H, Chua DT, Kwong DL, Al-Sarraf M, Chi KH, Hareyama M, et al. Chemotherapy in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an individual patient data meta-analysis of eight randomized trials and 1753 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006; 64:47-56; PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen L, Hu CS, Chen XZ, Hu GQ, Cheng ZB, Sun Y, Li WX, Chen YY, Xie FY, Liang SB, et al. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy plus adjuvant chemotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a phase 3 multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13:163-71; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70320-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dawson CW, Rickinson AB, Young LS. Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein inhibits human epithelial cell differentiation. Nature 1990; 344:777-80; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/344777a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gourzones C, Barjon C, Busson P. Host-tumor interactions in nasopharyngeal carcinomas. Semin Cancer Biol 2012; 22:127-36; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee SP. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma and the EBV-specific T cell response: prospects for immunotherapy. Seminars Cancer Biol 2002; 12:463-71; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1044-579X(02)00089-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mazeron MC. Value of anti-Epstein–Barr antibody detection in the diagnosis and management of undifferentiated carcinoma of the nasopharynx. Bull Cancer Radiother 1996; 83:3-7; PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gottschalk S, Heslop HE, Rooney CM. Adoptive immunotherapy for EBV-associated malignancies. Leuk Lymphoma 2005; 46:1-10; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/10428190400002202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Straathof KC, Bollard CM, Popat U, Huls MH, Lopez T, Morriss MC, Gresik MV, Gee AP, Russell HV, Brenner MK, et al. Treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma with Epstein–Barr virus–specific T lymphocytes. Blood 2005; 105:1898-904; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Comito MA, Sun Q, Lucas KG. Immunotherapy for Epstein–Barr virus-associated tumors. Leuk Lymphoma 2004; 45:1981-7; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/10428190410001700831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Comoli P, De Palma R, Siena S, Nocera A, Basso S, Del Galdo F, Schiavo R, Carminati O, Tagliamacco A, Abbate GF, et al. Adoptive transfer of allogeneic Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-specific cytotoxic T cells with in vitro antitumor activity boosts LMP2-specific immune response in a patient with EBV-related nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2004; 15:113-7; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/annonc/mdh027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bollard CM, Aguilar L, Straathof KC, Gahn B, Huls MH, Rousseau A, Sixbey J, Gresik MV, Carrum G, Hudson M, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte therapy for Epstein–Barr virus+ Hodgkin's disease. J Exp Med 2004; 200:1623-33; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20040890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lucas KG, Salzman D, Garcia A, Sun Q. Adoptive immunotherapy with allogeneic Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes for recurrent, EBV-positive Hodgkin disease. Cancer 2004; 100:1892-901; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/cncr.20188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sun Q, Burton R, Reddy V, Lucas KG. Safety of allogeneic Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes for patients with refractory EBV-related lymphoma. British journal of haematology 2002; 118:799-808; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03683.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith C, Tsang J, Beagley L, Chua D, Lee V, Li V, Moss DJ, Coman W, Chan KH, Nicholls J, et al. Effective treatment of metastatic forms of Epstein–Barr virus-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma with a novel adenovirus-based adoptive immunotherapy. Cancer Res 2012; 72:1116-25; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lutzky VP, Davis JE, Crooks P, Corban M, Smith MC, Elliott M, Morrison L, Cross S, Tscharke D, Panizza B, et al. Optimization of LMP-specific CTL expansion for potential adoptive immunotherapy in NPC patients. Immunol Cell Biol 2009; 87:481-8; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/icb.2009.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Louis CU, Straathof K, Bollard CM, Gerken C, Huls MH, Gresik MV, Wu MF, Weiss HL, Gee AP, Brenner MK, et al. Enhancing the in vivo expansion of adoptively transferred EBV-specific CTL with lymphodepleting CD45 monoclonal antibodies in NPC patients. Blood 2009; 113:2442-50; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2008-05-157222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Besser MJ, Shapira-Frommer R, Treves AJ, Zippel D, Itzhaki O, Hershkovitz L, Levy D, Kubi A, Hovav E, Chermoshniuk N, et al. Clinical responses in a phase II study using adoptive transfer of short-term cultured tumor infiltration lymphocytes in metastatic melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res 2010; 16:2646-55; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Benlalam H, Vignard V, Khammari A, Bonnin A, Godet Y, Pandolfino MC, Jotereau F, Dreno B, Labarriere N. Infusion of Melan-A/Mart-1 specific tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes enhanced relapse-free survival of melanoma patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2007; 56:515-26; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00262-006-0204-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kradin RL, Kurnick JT, Lazarus DS, Preffer FI, Dubinett SM, Pinto CE, Gifford J, Davidson E, Grove B, Callahan RJ, et al. Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and interleukin-2 in treatment of advanced cancer. Lancet 1989; 1:577-80; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)91609-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Kammula US, Hughes MS, Phan GQ, Citrin DE, Restifo NP, Robbins PF, Wunderlich JR, et al. Durable complete responses in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic melanoma using T-cell transfer immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2011; 17:4550-7; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Muranski P, Boni A, Wrzesinski C, Citrin DE, Rosenberg SA, Childs R, Restifo NP. Increased intensity lymphodepletion and adoptive immunotherapy–how far can we go? Nat Clin Pract Oncol 2006; 3:668-81; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncponc0666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. He J, Tang XF, Chen QY, Mai HQ, Huang ZF, Li J, Zeng YX. Ex vivo expansion of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients for adoptive immunotherapy. Chinese J Cancer 2012; 31:287-94; PMID:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kalpoe JS, Dekker PB, van Krieken JH, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Kroes AC. Role of Epstein–Barr virus DNA measurement in plasma in the clinical management of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in a low risk area. J Clin Pathol 2006; 59:537-41; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/jcp.2005.030544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chan AT, Lo YM, Zee B, Chan LY, Ma BB, Leung SF, Mo F, Lai M, Ho S, Huang DP, et al. Plasma Epstein–Barr virus DNA and residual disease after radiotherapy for undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002; 94:1614-9; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jnci/94.21.1614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Weber J, Atkins M, Hwu P, Radvanyi L, Sznol M, Yee C, Immunotherapy Task Force of the NCIIDSC. White paper on adoptive cell therapy for cancer with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes: a report of the CTEP subcommittee on adoptive cell therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2011; 17:1664-73; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yee C. Adoptive T-cell therapy for cancer: boutique therapy or treatment modality? Clin Cancer Res 2013; 19:4550-2; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wu R, Forget MA, Chacon J, Bernatchez C, Haymaker C, Chen JQ, Hwu P, Radvanyi LG. Adoptive T-cell therapy using autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for metastatic melanoma: current status and future outlook. Cancer J 2012; 18:160-75; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31824d4465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Louis CU, Straathof K, Bollard CM, Ennamuri S, Gerken C, Lopez TT, Huls MH, Sheehan A, Wu MF, Liu H, et al. Adoptive transfer of EBV-specific T cells results in sustained clinical responses in patients with locoregional nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Immunother 2010; 33:983-90; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181f3cbf4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Comoli P, Pedrazzoli P, Maccario R, Basso S, Carminati O, Labirio M, Schiavo R, Secondino S, Frasson C, Perotti C, et al. Cell therapy of stage IV nasopharyngeal carcinoma with autologous Epstein–Barr virus-targeted cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Clinl Oncol 2005; 23:8942-9; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.6195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lin CL, Lo WF, Lee TH, Ren Y, Hwang SL, Cheng YF, Chen CL, Chang YS, Lee SP, Rickinson AB, et al. Immunization with Epstein–Barr Virus (EBV) peptide-pulsed dendritic cells induces functional CD8+ T-cell immunity and may lead to tumor regression in patients with EBV-positive nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Res 2002; 62:6952-8; PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shi H, Liu L, Wang Z. Improving the efficacy and safety of engineered T cell therapy for cancer. Cancer letters 2013; 328:191-7; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Radvanyi LG, Bernatchez C, Zhang M, Fox PS, Miller P, Chacon J, Wu R, Lizee G, Mahoney S, Alvarado G, et al. Specific lymphocyte subsets predict response to adoptive cell therapy using expanded autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in metastatic melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18:6758-70; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dudley ME. Adoptive cell therapy for patients with melanoma. J Cancer 2011; 2:360-2; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.7150/jca.2.360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dudley ME, Yang JC, Sherry R, Hughes MS, Royal R, Kammula U, Robbins PF, Huang J, Citrin DE, Leitman SF, et al. Adoptive cell therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: evaluation of intensive myeloablative chemoradiation preparative regimens. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:5233-9; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chapuis AG, Thompson JA, Margolin KA, Rodmyre R, Lai IP, Dowdy K, Farrar EA, Bhatia S, Sabath DE, Cao J, et al. Transferred melanoma-specific CD8+ T cells persist, mediate tumor regression, and acquire central memory phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:4592-7; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1113748109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rosenberg SA, Dudley ME. Adoptive cell therapy for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. Curr Opin Immunol 2009; 21:233-40; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.coi.2009.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Secondino S, Zecca M, Licitra L, Gurrado A, Schiavetto I, Bossi P, Locati L, Schiavo R, Basso S, Baldanti F, et al. T-cell therapy for EBV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma: preparative lymphodepleting chemotherapy does not improve clinical results. Ann Oncol 2012; 23:435-41; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/annonc/mdr134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dudley ME, Gross CA, Langhan MM, Garcia MR, Sherry RM, Yang JC, Phan GQ, Kammula US, Hughes MS, Citrin DE, et al. CD8+ enriched "young" tumor infiltrating lymphocytes can mediate regression of metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2010; 16:6122-31; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhou J, Shen X, Huang J, Hodes RJ, Rosenberg SA, Robbins PF. Telomere length of transferred lymphocytes correlates with in vivo persistence and tumor regression in melanoma patients receiving cell transfer therapy. J Immunol 2005; 175:7046-52; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.7046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Paludan C, Schmid D, Landthaler M, Vockerodt M, Kube D, Tuschl T, Munz C. Endogenous MHC class II processing of a viral nuclear antigen after autophagy. Sci 2005; 307:593-6; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1104904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cejas PJ, Walsh MC, Pearce EL, Han D, Harms GM, Artis D, Turka LA, Choi Y. TRAF6 inhibits Th17 differentiation and TGF-beta-mediated suppression of IL-2. Blood 2010; 115:4750-7; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2009-09-242768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jin J, Sabatino M, Somerville R, Wilson JR, Dudley ME, Stroncek DF, Rosenberg SA. Simplified method of the growth of human tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in gas-permeable flasks to numbers needed for patient treatment. J Immunother 2012; 35:283-92; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31824e801f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.