Abstract

Environmental changes challenge plants and drive adaptation to new conditions, suggesting that natural biodiversity may be a source of adaptive alleles acting through phenotypic plasticity and/or micro-evolution. Crosses between accessions differing for a given trait have been the most common way to disentangle genetic and environmental components. Interestingly, such man-made crosses may combine alleles that never meet in nature. Another way to discover adaptive alleles, inspired by evolution, is to survey large ecotype collections and to use association genetics to identify loci of interest. Both of these two genetic approaches are based on the use of biodiversity and may eventually help us in identifying the genes that plants use to respond to challenges such as short-term stresses or those due to global climate change. In legumes, two wild species, Medicago truncatula and Lotus japonicus, plus the cultivated soybean (Glycine max) have been adopted as models for genomic studies. In this review, we will discuss the resources, limitations and future plans for a systematic use of biodiversity resources in model legumes to pinpoint genes of adaptive importance in legumes, and their application in breeding.

Keywords: Medicago truncatula, Lotus japonicus, Glycine max, GWAS, genetics, whole genome sequencing, gene expression

Introduction

The legume family (Leguminosae) is second only to cereals in economic and nutritional value. Grain legumes, such as common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), lentil (Lens culinaris), or chickpea (Cicer arietinum) provide on average 33% of human's dietary nitrogen and up to 60% in developing countries (O'Rourke et al., 2014). Altogether, grain legumes are grown on 115 million ha, with soybean for feed and food grown on 111 million ha, representing 276 million tons. The major fodder legume, alfalfa, is cultivated over 15 million ha for 340 million tons of forage1.

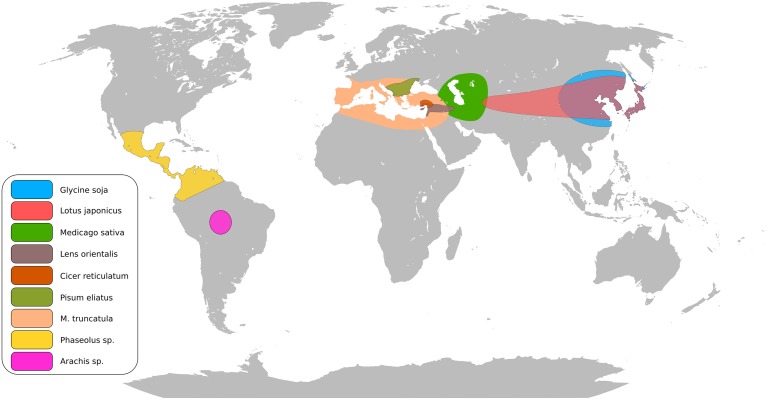

The legume family consists of approximately 20,000 species (Doyle and Lucknow, 2003). Legumes are often pioneer plants improving soil fertility and moderating harsh conditions, as demonstrated with Lotus corniculatus (Esperschütz et al., 2011). Figure 1 summarizes the centers of origin for several important cultivated and model legumes. Legumes establish symbiotic interactions with both rhizobia (the Rhizobium-legume symbiosis, RL) and arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi leading to formation of nitrogen-fixing nodules and phosphate acquiring mycorrhiza (Oldroyd, 2013). These traits play a vital role in ecosystems and sustainable crop production, and are central for efforts to decrease dependence on commercial fertilizers and substitute imported protein feeds with locally produced legume crops (Voisin et al., 2014). Aiming to uncover the genetic basis for these features, Medicago truncatula and Lotus japonicus, have come to supplement Arabidopsis, maize and rice as plant models. Through a mutant approach a core set of RL symbiosis genes has been identified in the two model legumes (Kouchi et al., 2010; Gough and Cullimore, 2011). Virtually all current knowledge about the perception of rhizobial signals, transduction and organogenesis originates from these studies. The RL and AM signaling pathways overlap and the genetic basis of this common symbiosis pathway comprises more than 10 genes (Parniske, 2008). Several mutants affected in RL symbiosis also show altered responses to root pathogens (Rey et al., 2013; Ben et al., 2013b) suggesting crosstalk between signaling pathways in symbiosis and diseases.

Figure 1.

Putative centers of origin of major legume crops and model legumes.

Translational biology (from models to crops) is still in its infancy. This could be due to lack of genetic variability, where the crop's orthologous gene is not polymorphic and thus not amenable to breeding. Strategies to introduce heterologous genes into crops may encounter technical difficulties, or societal issues such as consumers' acceptance. Genes identified in mutant-based approaches may also be unrelated to adaptation and responses to biotic and abiotic stresses encountered in agriculture or natural environments. Initial phenotypic screens may not have been set up to target “adaptive” traits such as seed yield, biomass, or fitness. Nonetheless, legume crops do benefit from models: the RCT1 gene from M. truncatula provides resistance to anthracnose in alfalfa (Yang et al., 2008). Wild species also contributed to the improvement of crops: a high-protein allele has been introgressed into soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] from its wild progenitor, Glycine soja Sieb. and Zucc (Sebolt et al., 2000; Vaughn et al., 2014).

Many legume crops have limited genetic diversity due to bottlenecks from domestication and selective breeding (Gross and Olsen, 2010; Roorkiwal et al., 2014). Proper characterization and evaluation of germplasm collections as sources of adaptive alleles, and their utilization in breeding are often limited or neglected (Smýkal et al., 2015). However, the anticipated climate change may require explicit efforts to breed for local adaptation. The use of wild relatives of cultivated legumes crops has received limited attention as well. As a consequence, selection of new cultivars and improving production technologies for food legume crops are not proceeding at the same pace as for cereal crops.

M. truncatula and L. japonicus as members of the Hologalegina clade (which contains cultivated legumes such as pea, chickpea), and G. max as a representative of the Phaseoloid clade (containing mungbean and soybean) can serve as models for cool season and tropical season legume crops, respectively (Doyle and Lucknow, 2003; Zhu et al., 2005). The high degree of synteny between these model plants and their legume crops relatives can been exploited to improve genetic maps and identify candidate genes for agronomic traits in less well-characterized crops, as has been described for leaf size in cowpea (Potorff et al., 2012), drought adaptation traits in faba bean (Kharzaei et al., 2014) or symbiotic genes in pea (Novak et al., 2012). In this Perspective, we will discuss the resources, limitations and future plans for a systematic use of biodiversity resources in model legumes to pinpoint genes of adaptive importance in legumes.

Exploring the natural diversity of Medicago truncatula

Medicago truncatula is closely related to alfalfa. Together with L. japonicus, M. truncatula has been essential for studies of RL and AM symbioses. In addition, agronomic and quality traits (Julier et al., 2007), including drought and salinity tolerance (Friesen et al., 2014), seed development and composition (Vandecasteele et al., 2011), and disease resistance (e.g., Ben et al., 2013) have been targeted. Consequently, this species has an excellent array of germplasm, molecular, and genomic resources.

Studies of Medicago populations focused on collections from the Mediterranean basin, its center of diversity. Work in France led to the establishment of extensive germplasm resources (Thoquet et al., 2002), including accessions covering M. truncatula's natural range plus strategically selected biparental crosses and derived recombinant inbred lines. Additional material is available from SARDI (Ellwood et al., 2006) and USDA-GRIN. Another valuable germplasm resource is the Tnt1 insertion population created at the Noble Foundation, which provides knockout mutants for reverse genetics and characterization of candidate genes (Pislariu et al., 2012). The genome sequence released in 2011 (Young et al., 2011) and refined in 2014 (Tang et al., 2014) established M. truncatula as an outstanding system for genome studies. Altogether the Mt4.0 assembly covers 360 Mb and gene annotation uncovers 31,661 high confidence predicted genes.

The underlying genome architecture was first described in Branca et al. (2011) using 26 accessions broadly spanning M. truncatula's range, at 30x sequence coverage. This uncovered four to six SNPs/kb and LD decays reaching half its initial value within 3–4 kb, similar to that of Arabidopsis (Kim et al., 2007).

More than 20,000 annotated genes from 56 accessions were used to identify targets of positive selection (Paape et al., 2013). Around 1% of sampled genes harbored a signature of positive selection, while 50–75% of non-synonymous polymorphisms were subject to purifying selection. Among putative targets of selection were genes involved in defense against pathogens and herbivores and in relationship with rhizobial symbionts.

Local adaptation and adaptive clines were examined in 202 accessions at 2 million SNPs, identifying loci responsible for adaptation to climatic gradients: annual mean temperature (AMT), precipitation in the wettest month (PWM), and isothermality (Yoder et al., 2014). The strongest associations tagged genome regions containing genes with predicted roles in tolerance to temperature, drought, herbivores or pathogens. The candidate loci were further tested and validated using climate-controlled tests. For AMT and PWM, a history of soft selective sweeps acting on loci underlying adaptation was indicated.

GWAS based on 6 million SNPs, identified by re-sequencing 226 M. truncatula accessions, revealed candidate genes underlying phenotypic variation in several plant functional traits (Stanton-Geddes et al., 2013). For flowering time and trichome density, peaks were associated with well-supported candidates (MtFD for flowering time; unshaven in the case of trichome density). For rhizobium symbiosis, previously characterized nodulation genes (SERK2, MtnodGRP3, MtMMPL1, NFP, CaML3, MtnodGRP3A) were confirmed, and novel loci were identified with annotation and/or expression profiles that supported a role in nodule formation.

Population genomics revealed candidate regions associated with local adaptation (Friesen et al., 2010, 2014) to saline environments, by searching for SNP that assorted by population i.e., two populations from saline environments vs. two from non-saline environments. The analyses pinpointed signaling pathways for abiotic stress tolerance involving ABA and MeJA, production of putative osmoprotectant, and candidates linked to biotic interactions. A strategy for salt stress avoidance through early flowering was suggested, specifically a non-synonymous SNP that changes a highly conserved amino acid in the Medicago ortholog of CONSTANS (Pierre et al., 2011).

M. truncatula is a host for leaf and soil-borne pathogens (Ameline-Torregrosa et al., 2007; Ramírez-Suero et al., 2010; Rispail and Rubiales, 2014). Quantitative resistance loci for root diseases have been described for the interaction with Ralstonia solanacearum (Ben et al., 2013a), the oomycete Aphanomyces euteiches (Ae) (Djébali et al., 2009; Pilet-Nayel et al., 2009), and Verticillium alfalfae (Ben et al., 2013b). Bonhomme et al. (2014) utilized GWAS to map loci associated with Ae resistance. This identified several candidate genes and pinpointed two major loci on chromosome 3, that co-located with previously described QTLs (Djébali et al., 2009; Pilet-Nayel et al., 2009). Intriguingly, the resistance allele of the candidate gene seemed to be the ancestral form, although the pathogen and the resistant host plant do not occur naturally in the same geographical regions. Another study of Ae resistance with 136 lines from 14 Tunisian populations, not naturally exposed to the oomycete, suggested that resistance can occur as a by-product of adaptation to water stress (Djébali et al., 2013).

Clearly, the evaluation of naturally occurring variations in M. truncatula, making use of its well-characterized biodiversity and feature-rich genomic tools, is becoming a powerful strategy of investigation. Identification of candidate genes for major traits is likely to expand rapidly.

Lotus resources for functional analysis of natural diversity

Several Lotus species are cultivated as forage legumes, especially in grassland areas characterized by harsh environments, including windy and salty coastal climates (Escaray et al., 2012). The genetic background for such plasticity and adaptation to adverse conditions in poor soils, flooding, drought, salt and other abiotic stresses is important for plant production in a world facing climate changes. Model plants are essential for unequivocal identification of genetic regulators, and one of the diploid and self-fertile Lotus species, L. japonicus, was proposed in 1992 as a model system for classical and molecular genetics (Handberg and Stougaard, 1992). Since then, genetic and physical maps, F2 and recombinant inbred line populations, transformation protocols and a reference genome sequence have been established (Hayashi et al., 2001; Kawaguchi et al., 2001, 2005; Lohar et al., 2001; Sandal et al., 2002, 2012; Sato et al., 2008). These resources have facilitated molecular cloning of central genetic components required for endosymbiosis with rhizobia and arbuscular mycorrhiza (Schauser et al., 1999; Stracke et al., 2002; Radutoiu et al., 2003; Imaizumi-Anraku et al., 2005; Yano et al., 2008), positioning L. japonicus as a major model system for legume research. In a broader context, the L. japonicus resources were also exploited for comparative genomic approaches in a number of crop legumes, including pea, bean, and lupin, and for gene cloning in pea (Choi et al., 2004; Stracke et al., 2004; Fredslund et al., 2005; Hougaard et al., 2008; Li et al., 2010; McConnell et al., 2010; Nelson et al., 2010; Humphry et al., 2011; Krusell et al., 2011; Cruz-Izquierdo et al., 2012; Shirasawa et al., 2014).

Genetic analysis of natural variation within L. japonicus has now also been initiated. First, biparental populations have been used for QTL mapping of agronomic traits, host specificity, and nitrogen fixation efficiency using the three central experimental genotypes MG-20, Gifu and L. burtii (Gondo et al., 2007; Sandal et al., 2012; Tominaga et al., 2012), and diversity information has been exploited for evaluation the impact of Nod factor perception on rhizobium host range (Radutoiu et al., 2007; Bek et al., 2010). Second, a collection of ~200 L. japonicus accessions is managed and distributed by the Japanese National Bioresource Program (Hashiguchi et al., 2012). Phenotypic characterization has been carried out for some of these accessions (Kai et al., 2010) and so far 130 of them have been re-sequenced to facilitate GWAS analysis (Sato and Andersen, unpublished). There is a strong interest in the community for taking advantage of these new resources, and the accessions have been phenotyped for flowering time, trichome phenotype, nodulation capacity, salt tolerance, nematode resistance and root growth traits (Poch et al., 2007; Kubo et al., 2009; Gossmann et al., 2012; Wakabayashi et al., 2014; and unpublished results).

To take full advantage of GWAS-based genetic analysis and bring it to fruition in terms of functional characterization of genes, additional resources are needed. Expression data, high quality annotation and homology information is available for L. japonicus, facilitating quick selection of the most promising candidate genes for further investigation (Gonzales et al., 2005; Høgslund et al., 2009; Li et al., 2012; Verdier et al., 2013). Likewise, easy access to insertion mutants is critical to validate candidate gene involvement in a phenotype. Here, L. japonicus offers access to a unique resource in the non-transgenic LORE1 collection, which currently holds 40,000 annotated lines, with an additional 60,000 lines already characterized and soon to be released, bringing the total of annotated insertions to more than 500,000 (Urbanski et al., 2012; Andersen, unpublished). Together with the TILLING population this offers a comprehensive platform for mutant analysis (Perry et al., 2003).

The sum of these resources makes L. japonicus attractive as a model species, and the availability of non-transgenic insertion mutants offers the unique possibility of phenotyping L. japonicus and other legume diversity panels under similar conditions to estimate the degree of conservation of the genetic networks governing phenotypic responses across legumes and facilitating functional follow-up by characterization of candidate LORE1 mutant phenotypes under field conditions.

Soybean benefits from comparison with its wild progenitors

Soybean is the most important legume crop and one of the largest global sources of vegetable oil and protein for people and livestock (Graham and Vance, 2003). Not surprisingly, the genome resource for soybean first published in 2010 is among the best for plants (Schmutz et al., 2010). For the initial assembly, more than 950 Mbp of the overall 1115 Mbp genome were completed through 8X Sanger shotgun sequencing and 98% could be anchored to specific chromosomal positions with few gaps. With this outstanding resource as a starting point, genome re-sequencing, genome-wide scans for selection, and GWAS have been fruitful in Glycine sp.

As a community-wide resource for genotyping a “SoySNP50K iSelect BeadChip” (Song et al., 2013) was designed from six cultivated and two wild soybean, aligned to the soybean genome reference. A total of 47,337 SNP calls were identified when tested against 96 landraces, 96 elite cultivars, and 96 wild accessions. This chip is used in many recent soybean GWAS publications.

Protein and oil content in the soybean seed are of special interest. In a GWAS analysis of 298 genotypes, Hwang et al. (2014) uncovered 40 associated SNPs in 17 different regions. One region was a long-sought protein/oil QTL on linkage group I (chromosome 20). This gene has been the target of QTL mapping research for many years, but earlier (biparental) studies struggled to localize the target gene to a region smaller than 8 Mbp (Bolon et al., 2011). In a second protein/oil GWAS study, Vaughn et al. (2014) discovered a more diagnostic and presumably more tightly linked locus as well as additional novel seed composition loci.

Further GWAS studies focused on abiotic and biotic stress. Concerning water deficit tolerance, Dhanapal et al. (2015) characterized carbon isotope ratios for 373 genotypes across four environments and 2 years, and described SNP tagging of 21 loci. Tolerance to low phosphorous is another important trait and GWAS enabled Zhang et al. (2014) to identify six regions associated with P efficiency. Closer examination of a region on chromosome 8 across 192 soybean accessions revealed a candidate, GmACP1 (an acid phosphatase). Favorable alleles and haplotypes of GmACP1 are associated with higher enzyme activity. Finally, resistance to the fungal pathogen Fusarium virguliforme, the cause of sudden death syndrome (SDS), was analyzed through GWAS in two association panels of elite cultivars by Wen et al. (2014). A total of 20 loci underlying SDS resistance were discovered, seven in regions previously described and 13 novel ones. One of these loci overlapped a previously cloned SDS resistance gene, Rfs2.

The availability of genome resources has enabled whole genome re-sequencing, focusing on soybean domestication from wild soybean (G. soja). For example, G. soja has been found to differ from the reference genome by only 0.31% (Kim et al., 2010). Re-sequencing 17 wild and 14 cultivated soybean genomes revealed unusually high levels of linkage disequilibrium (LD) with LD blocks greater than 1 Mb in cultivated soybean (Lam et al., 2010). Based on Fst scans across the genome, putative domestication regions (areas of high Fst) could be identified. Detailed mapping pinpointed smaller regions associated with known domestication traits such as twinning and stem elongation. By re-sequencing 55 accessions, Li et al. (2013) show that selection during early domestication led to more pronounced reduction in genetic diversity than the move from landraces to elite cultivars. Clusters of selection hotspots were observed involving 4.38% of total annotated genes. Finally, Li et al. (2014) initiated the first step toward a soybean pan-genome, generating de novo genome sequences independent of the soybean (G. max Williams-82) reference. This is important for characterizing structural variation, including copy number variation and for identifying core vs. dispensable portions of the soybean genome.

Making the most of legumes – collaborations across species

To date, research efforts have focused on developing the resources, reference genome sequences and catalogs of natural diversity and germplasm, required to carry out association studies within a species. With the successful establishment of these prerequisites, the time has come to consider the possibilities offered by the resources, along with those emerging in multiple legume species. While GWAS is a powerful tool for genetic analysis and causal allele identification, it also comes with inherent challenges. Inaccuracies in geno- and phenotyping combined with population sampling and structure can all lead to false positive signals. However, these confounding factors are species-specific, as the legume resources have largely been developed independently for each species. As such, genotype-phenotype associations detected recurrently in at least two legume species would therefore be strongly mutually supportive.

Leveraging these potential gains in GWAS candidate gene confidence will require a new paradigm for GWAS phenotyping, where multi-site, multi-year phenotyping strategies are combined with multi-species trials. Approaches where multiple legume species are grown side-by-side for phenotyping at multiple geographical locations will not be relevant for all traits, but obvious traits suitable for analysis are abiotic and broad host-range biotic stresses where similar adaptive strategies could be in play across species. Such phenotyping strategies have the potential to break new ground in the understanding of environmental adaptation, but organization of international consortia that could successfully implement these approaches would require a high level of (re-)organization, for researchers, breeders, and funding bodies.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to all authors whose relevant work was not cited due to space constraints.

Footnotes

References

- Ameline-Torregrosa C., Cazaux M., Danesh D., Chardon F., Cannon S. B., Esquerré-Tugayé M.-T., et al. (2007). Genetic dissection of resistance to anthracnose and powdery mildew in Medicago truncatula. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 21, 61–69 10.1094/MPMI-21-1-0061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bek A. S., Sauer J., Thygesen M. B., Duus J. Ø., Petersen B. O., Thirup S., et al. (2010). Improved characterization of nod factors and genetically based variation in LysM receptor domains identify amino acids expendable for nod factor recognition in Lotus spp. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23, 58–66 10.1094/MPMI-23-1-0058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben C., Debellé F., Berges H., Bellec A., Jardinaud M.-F., Anson P., et al. (2013a). MtQRRS1, an R-locus required for Medicago truncatula quantitative resistance to Ralstonia solanacearum. New Phytol. 199, 758–772. 10.1111/nph.12299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben C., Toueni M., Montanari S., Tardin M.-C., Fervel M., Negahi A., et al. (2013b). Natural diversity in the model legume Medicago truncatula allows identifying distinct genetic mechanisms conferring partial resistance to Verticillium wilt. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 317–332 10.1093/jxb/ers337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolon Y.-T., Haun W. J., Xu W. W., Grant D., Stacey M. G., Nelson R. T., et al. (2011). Phenotypic and genomic analyses of a fast neutron mutant population resource in soybean. Plant Physiol. 156, 240–253. 10.1104/pp.110.170811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonhomme M., André O., Badis Y., Ronfort J., Burgarella C., Chantret N., et al. (2014). High-density genome-wide association mapping implicates an F-box encoding gene in Medicago truncatula resistance to Aphanomyces euteiches. New Phytol. 201, 1328–1342. 10.1111/nph.12611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branca A., Paape T. D., Zhou P., Briskine R., Farmer A. D., Mudge J., et al. (2011). Whole-genome nucleotide diversity, recombination, and linkage disequilibrium in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, E864–E870 10.1073/pnas.1104032108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H.-K., Mun J.-H., Kim D.-J., Zhu H., Baek J.-M., Mudge J., et al. (2004). Estimating genome conservation between crop and model legume species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 15289–15294. 10.1073/pnas.0402251101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Izquierdo S., Avila C. M., Satovic Z., Palomino C., Gutierrez N., Ellwood S. R., et al. (2012). Comparative genomics to bridge Vicia faba with model and closely-related legume species: stability of QTLs for flowering and yield-related traits. Theor. Appl. Genet. 125, 1767–1782. 10.1007/s00122-012-1952-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanapal A. P., Ray J. D., Singh S. K., Hoyos-Villegas V., Smith J. R., Purcell L. C., et al. (2015). Genome-wide association study (GWAS) of carbon isotope ratio (δ (13)C) in diverse soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] genotypes. Theor. Appl. Genet. 128, 73–91. 10.1007/s00122-014-2413-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djébali N., Aribi S., Taamalli W., Arraouadi S., Aouani M. E., Badri M. (2013). Natural variation of Medicago truncatula resistance to Aphanomyces euteiches. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 135, 831–843. 10.1007/s10658-012-0127-x24283472 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Djébali N., Jauneau A., Ameline-Torregrosa C., Chardon F., Jaulneau V., Mathé C., et al. (2009). Partial resistance of Medicago truncatula to Aphanomyces euteiches is associated with protection of the root stele and is controlled by a major QTL rich in proteasome-related genes. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 22, 1043–1055. 10.1094/MPMI-22-9-1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle J. J., Lucknow M. A. (2003). The rest of the iceberg. Legume diversity and evolution in a phylogenetic context. Plant Physiol. 131, 900–910 10.1104/pp.102.018150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellwood S. R., D'Souza N. K., Kamphuis L. G., Burgess T. I., Nair R. M., Oliver R. P. (2006). SSR analysis of the Medicago truncatula SARDI core collection reveals substantial diversity and unusual genotype dispersal throughout the Mediterranean basin. Theor. Appl. Genet. 112, 977–983. 10.1007/s00122-005-0202-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escaray F. J., Menendez A. B., Gárriz A., Pieckenstain F. L., Estrella M. J., Castagno L. N., et al. (2012). Ecological and agronomic importance of the plant genus Lotus. Its application in grassland sustainability and the amelioration of constrained and contaminated soils. Plant Sci. Int. J. Exp. Plant Biol. 182, 121–133. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esperschütz J., Welzl G., Schreiner K., Buegger F., Munch J. C., Schloter M. (2011). Incorporation of carbon from decomposing litter of two pioneer plant species into microbial communities of the detritusphere: C fluxes from litter into microorganisms in initial ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 320, 48–55. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02286.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredslund J., Schauser L., Madsen L. H., Sandal N., Stougaard J. (2005). PriFi: using a multiple alignment of related sequences to find primers for amplification of homologs. Nucl. Acids Res. 33 (suppl 2), W516-W520. 10.1093/nar/gki425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesen M. L., Cordeiro M. A., Penmetsa R. V., Badri M., Huguet T., Aouani M. E., et al. (2010). Population genomic analysis of Tunisian Medicago truncatula reveals candidates for local adaptation. Plant J. 63, 623–635. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04267.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesen M. L., von Wettberg E. J., Badri M., Moriuchi K. S., Barhoumi F., Chang P. L., et al. (2014). The ecological genomic basis of salinity adaptation in Tunisian Medicago truncatula. BMC Genomics 15:1160. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gondo T., Sato S., Okumura K., Tabata S., Akashi R., Isobe S. (2007). Quantitative trait locus analysis of multiple agronomic traits in the model legume Lotus japonicus. Genome 50, 627–637. 10.1139/g07-040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales M. D., Archuleta E., Farmer A., Gajendran K., Grant D., Shoemaker R., et al. (2005). The Legume Information System (LIS): an integrated information resource for comparative legume biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, D660–D665. 10.1093/nar/gki128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossmann J. A., Markmann K., Brachmann A., Rose L. E., Parniske M. (2012). Polymorphic infection and organogenesis patterns induced by a Rhizobium leguminosarum isolate from Lotus root nodules are determined by the host genotype. New Phytol. 196, 561–573. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04281.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough C., Cullimore J. (2011). Lipo-chitooligosaccharide signaling in endosymbiotic plant-microbe interactions. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 24, 867–878. 10.1094/MPMI-01-11-0019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham P. H., Vance C. P. (2003). Legumes: importance and constraints to greater use. Plant Physiol. 131, 872–877. 10.1104/pp.017004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross B. L., Olsen K. M. (2010). Genetic perspectives on crop domestication. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 529–537. 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handberg K., Stougaard J. (1992). Lotus japonicus, an autogamous, diploid legume species for classical and molecular genetics. Plant J. 2, 487–496 10.1111/j.1365-313X.1992.00487.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hashiguchi M., Abe J., Aoki T., Anai T., Suzuki A., Akashi R. (2012). The National BioResource Project (NBRP) Lotus and Glycine in Japan. Breed. Sci. 61, 453–461. 10.1270/jsbbs.61.453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M., Miyahara A., Sato S., Kato T., Yoshikawa M., Taketa M., et al. (2001). Construction of a genetic linkage map of the model legume Lotus japonicus using an intraspecific F2 population. DNA Res. 8, 301–310. 10.1093/dnares/8.6.301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Høgslund N., Radutoiu S., Krusell L., Voroshilova V., Hannah M. A., Goffard N., et al. (2009). Dissection of symbiosis and organ development by integrated transcriptome analysis of Lotus japonicus mutant and wild-type plants. PloS ONE 4:e6556 10.1371/journal.pone.0006556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hougaard B. K., Madsen L. H., Sandal N., de Carvalho Moretzsohn M., Fredslund J., Schauser L., et al. (2008). Legume anchor markers link syntenic regions between Phaseolus vulgaris, Lotus japonicus, Medicago truncatula and Arachis. Genetics 179, 2299–2312 10.1534/genetics.108.090084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphry M., Reinstädler A., Ivanov S., Bisseling T., Panstruga R. (2011). Durable broad-spectrum powdery mildew resistance in pea er1 plants is conferred by natural loss-of-function mutations in PsMLO1. Mol. Plant Pathol. 12, 866–878. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00718.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang E.-Y., Song Q., Jia G., Specht J. E., Hyten D. L., Costa J., et al. (2014). A genome-wide association study of seed protein and oil content in soybean. BMC Genomics 15:1. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaizumi-Anraku R., Takeda H., Charpentier M., Perry J., Miwa H., Umehara J., et al. (2005). Plastid proteins crucial for symbiotic fungal and bacterial entry into plant roots. Nature 433, 527–531. 10.1038/nature03237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julier B., Huguet T., Chardon F., Ayadi R., Pierre J.-B., Prosperi J.-M., et al. (2007). Identification of quantitative trait loci influencing aerial morphogenesis in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Theor. Appl. Genet. 114, 1391–1406. 10.1007/s00122-007-0525-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai S., Tanaka H., Hashiguchi M., Iwata H., Akashi R. (2010). Analysis of genetic diversity and morphological traits of Japanese Lotus japonicus for establishment of a core collection. Breed. Sci. 60, 436–446 10.1270/jsbbs.60.436 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi M., Motomura T., Imaizumi-Anraku H., Akao S., Kawasaki S. (2001). Providing the basis for genomics in Lotus japonicus: the accessions Miyakojima and Gifu are appropriate crossing partners for genetic analyses. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266, 157–166. 10.1007/s004380100540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi M., Pedrosa-Harand A., Yano K., Hayashi M., Murooka Y., Saito K., et al. (2005). Lotus burttii takes a position of the third corner in the lotus molecular genetics triangle. DNA Res. 12, 69–77. 10.1093/dnares/12.1.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharzaei H., O'Sullivan D. M., Sillanpää M. J., Stoddard F. L. (2014). Use of synteny to identify candidate genes underlying QTL controlling stomatal traits in faba bean (Vicia faba L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 127, 2371–2385. 10.1007/s00122-014-2383-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. Y., Lee S., Van K., Kim T.-H., Jeong S.-C., Choi I.-Y., et al. (2010). Whole-genome sequencing and intensive analysis of the undomesticated soybean (Glycine soja Sieb. and Zucc.) genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 22032–22037. 10.1073/pnas.1009526107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Plagnol V., Hu T. T., Toomajian C., Clark R. M., Ossowski S., et al. (2007). Recombination and linkage disequilibrium in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Genet. 39, 1151–1155. 10.1038/ng2115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouchi H., Imaizumi-Anraku H., Hayashi M., Hakoyama T., Nakagawa T., Umehara Y., et al. (2010). How many peas in a pod? legume genes responsible for mutualistic symbioses underground. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 1381–1397 10.1093/pcp/pcq107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krusell L., Sato N., Fukuhara I., Koch B. E. V., Grossmann C., Okamoto S., et al. (2011). The Clavata2 genes of pea and Lotus japonicus affect autoregulation of nodulation. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 65, 861–871. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04474.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo M., Ueda H., Park P., Kawaguchi M., Sugimoto Y. (2009). Reactions of Lotus japonicus ecotypes and mutants to root parasitic plants. J. Plant Physiol. 166, 353–362. 10.1016/j.jplph.2008.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam H.-M., Xu X., Liu X., Chen W., Yang G., Wong F.-L., et al. (2010). Resequencing of 31 wild and cultivated soybean genomes identifies patterns of genetic diversity and selection. Nat. Genet. 42, 1053–1059. 10.1038/ng.715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Dai X., Liu T., Zhao P. X. (2012). LegumeIP: an integrative database for comparative genomics and transcriptomics of model legumes. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1221–D1229. 10.1093/nar/gkr939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Zhuang L.-L., Ambrose M., Rameau C., Hu X.-H., Yang J., et al. (2010). Genetic analysis of ele mutants and comparative mapping of ele1 locus in the control of organ internal asymmetry in garden pea. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 52, 528–535. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00949.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhao S., Ma J., Li D., Yan L., Li J., et al. (2013). Molecular footprints of domestication and improvement in soybean revealed by whole genome re-sequencing. BMC Genomics 14:579. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhou G., Ma J., Jiang W., Jin L., Zhang Z., et al. (2014). De novo assembly of soybean wild relatives for pan-genome analysis of diversity and agronomic traits. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 1045–1052. 10.1038/nbt.2979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohar D. P., Schuller K., Buzas D. M., Gresshoff P. M., Stiller J. (2001). Transformation of Lotus japonicus using the herbicide resistance bar gene as a selectable marker. J. Exp. Bot. 52, 1697–1702. 10.1093/jexbot/52.361.1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell M., Mamidi S., Lee R., Chikara S., Rossi M., Papa R., et al. (2010). Syntenic relationships among legumes revealed using a gene-based genetic linkage map of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Appl. Genet. Theor. 121, 1103–1116. 10.1007/s00122-010-1375-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M. N., Moolhuijzen P. M., Boersma J. G., Chudy M., Lesniewska K., Bellgard M., et al. (2010). Aligning a new reference genetic map of Lupinus angustifolius with the genome sequence of the model legume, Lotus japonicus. DNA Res. 17, 73–83. 10.1093/dnares/dsq001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak K., Biedermannova E., Vondrys J. (2012). Functional markers delimiting a Medicago ortholoue of pea symbiotic gene NOD3. Euphytica 186, 761–777. 10.1007/s10681-011-0586-821802605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke J. A., Bolon Y.-T., Bucciarelli B., Vance C. P. (2014). Legume genomics: understanding biology through DNA and RNA sequencing. Ann. Bot. 113, 1107–1120. 10.1093/aob/mcu072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd G. E. D. (2013). Speak, friend, and enter: signalling systems that promote beneficial symbiotic associations in plants. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 252–263. 10.1038/nrmicro2990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paape T., Bataillon T., Zhou P. J Y, Kono T., Briskine R., Young N. D., et al. (2013). Selection, genome-wide fitness effects and evolutionary rates in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Mol. Ecol. 22, 3525–3538. 10.1111/mec.12329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parniske M. (2008). Arbuscular mycorrhiza: the mother of plant root endosymbioses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 763–775. 10.1038/nrmicro1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. A., Wang T. L., Welham T. J., Gardner S., Pike J. M., Yoshida S., et al. (2003). A TILLING reverse genetics tool and a web-accessible collection of mutants of the legume Lotus japonicus. Plant Physiol. 131, 866–871. 10.1104/pp.102.017384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierre J.-P., Bogard M., Herrmann D., Huyghe C., Julier B. (2011). A CONSTANS-like gene candidate that could explain mosy of the genetic variation for flowering date in Medicago truncatula. Mol. Breeding 28, 25–35 10.1007/s11032-010-9457-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pilet-Nayel M.-L., Prospéri J.-M., Hamon C., Lesné A., Lecointe R., Le Goff I., et al. (2009). AER1, a major gene conferring resistance to Aphanomyces euteiches in Medicago truncatula. Phytopathology 99, 203–208. 10.1094/PHYTO-99-2-0203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pislariu C. I., Murray J. D., Wen J., Cosson V., Muni R. R. D., Wang M., et al. (2012). A Medicago truncatula tobacco retrotransposon insertion mutant collection with defects in nodule development and symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Plant Physiol. 159, 1686–1699 10.1104/pp.112.197061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poch H. L. C., López R. H. M., Clark S. J. (2007). Ecotypes of the model legume Lotus japonicus vary in their interaction phenotypes with the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Ann. Bot. 99, 1223–1229. 10.1093/aob/mcm058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potorff M., Ehlers J. D., Fatoku C., Roberts P. A., Close T. J. (2012). Leaf morphology incowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.): QTL ananlysis, physical mapping and identifying a candidate gene using synteny with model legume species. BMC Genomics 13:234 10.1186/1471-2164-13-234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radutoiu S., Madsen L. H., Madsen E. B., Felle H. H., Umehara Y., Grønlund M., et al. (2003). Plant recognition of symbiotic bacteria requires two LysM receptor-like kinases. Nature 425, 585–592. 10.1038/nature02039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radutoiu S., Madsen L. H., Madsen E. B., Jurkiewicz A., Fukai E., Quistgaard E. M. H., et al. (2007). LysM domains mediate lipochitin-oligosaccharide recognition and Nfr genes extend the symbiotic host range. EMBO J. 26, 3923–3935. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Suero M., Khanshour A., Martinez Y., Rickauer M. (2010). A study on the susceptibility of the model legume plant Medicago truncatula to the soil-borne pathogen Fusarium oxysporum. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 126, 517–530 10.1007/s10658-009-9560-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rey T., Nars A., Bonhomme M., Bottin A., Huguet S., Balzergue S., et al. (2013). NFP, a LysM protein controlling Nod factor perception, also intervenes in Medicago truncatula resistance to pathogens. New Phytol. 198, 875–886. 10.1111/nph.12198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rispail N., Rubiales D. (2014). Identification of sources of quantitative resistance to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. medicaginis in Medicago truncatula. Plant Dis. 98, 667–673 10.1094/PDIS-03-13-0217-RE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roorkiwal M., von Wettberg E. J., Upadhyaya H. D., Warschefsky E., Rathore A., Varshney R. K. (2014). Exploring germplasm diversity to understand the domestication process in Cicer spp. using SNP and DArT markers. PLoS ONE 9:e102016. 10.1371/journal.pone.0102016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandal N., Jin H., Rodriguez-Navarro D. N., Temprano F., Cvitanich C., Brachmann A., et al. (2012). A set of Lotus japonicus Gifu x Lotus burttii recombinant inbred lines facilitates map-based cloning and QTL mapping. DNA Res. 19, 317–323. 10.1093/dnares/dss014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandal N., Krusell L., Radutoiu S., Olbryt M., Pedrosa A., Stracke S., et al. (2002). A genetic linkage map of the model legume Lotus japonicus and strategies for fast mapping of new loci. Genetics 161, 1673–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S., Nakamura Y., Kaneko T., Asamizu E., Kato T., Nakao M., et al. (2008). Genome structure of the legume, Lotus japonicus. DNA Res. 15, 227–239. 10.1093/dnares/dsn008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauser L., Roussis A., Stiller J., Stougaard J. (1999). A plant regulator controlling development of symbiotic root nodules. Nature 402, 191–195. 10.1038/46058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmutz J., Cannon S. B., Schlueter J., Ma J., Mitros T., Nelson W., et al. (2010). Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature 463, 178–183. 10.1038/nature08670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebolt A. M., Shoemaker R. C., Diers B. W. (2000). Analysis of a quantitative trait locus allele from wild soybean that increases seed protein concentration in soybean. Crop. Sci. 40, 1438 10.2135/cropsci2000.4051438x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasawa K., Isobe S., Tabata S., Hirakawa H. (2014). Kazusa marker DataBase: a database for genomics, genetics, and molecular breeding in plants. Breed. Sci. 64, 264–271. 10.1270/jsbbs.64.264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smýkal P., Coyne C. J., Ambrose M. J., Maxted N., Schaefer H., Blair M. W., et al. (2015). Legume crops phylogeny and genetic diversity for science and breeding. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 34, 43–104 10.1080/07352689.2014.897904 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song Q., Hyten D. L., Jia G., Quigley C. V., Fickus E. W., Nelson R. L., et al. (2013). Development and evaluation of SoySNP50K, a high-density genotyping array for soybean. PloS ONE 8:e54985. 10.1371/journal.pone.0054985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton-Geddes J., Paape T., Epstein B., Briskine R., Yoder J., Mudge J., et al. (2013). Candidate Genes and genetic architecture of symbiotic and agronomic traits revealed by whole-genome, sequence-based association genetics in Medicago truncatula. PLoS ONE 8:e65688. 10.1371/journal.pone.0065688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracke S., Kistner C., Yoshida S., Mulder L., Sato S., Kaneko T., et al. (2002). A plant receptor-like kinase required for both bacterial and fungal symbiosis. Nature 417, 959–962. 10.1038/nature00841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracke S., Sato S., Sandal N., Koyama M., Kaneko T., Tabata S., et al. (2004). Exploitation of colinear relationships between the genomes of Lotus japonicus, Pisum sativum and Arabidopsis thaliana, for positional cloning of a legume symbiosis gene. Theor. Appl. Genet. 108, 442–449. 10.1007/s00122-003-1438-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H., Krishnakumar V., Bidwell S., Rosen B., Chan A., Zhou S., et al. (2014). An improved genome release (version Mt4.0) for the model legume Medicago truncatula. BMC Genomics 15:312. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoquet P., Ghérardi M., Journet E.-P., Kereszt A., Ané J.-M., Prosperi J.-M., et al. (2002). The molecular genetic linkage map of the model legume Medicago truncatula: an essential tool for comparative legume genomics and the isolation of agronomically important genes. BMC Plant Biol. 2:1. 10.1186/1471-2229-2-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga A., Gondo T., Akashi R., Zheng S.-H., Arima S., Suzuki A. (2012). Quantitative trait locus analysis of symbiotic nitrogen fixation activity in the model legume Lotus japonicus. J. Plant Res. 125, 395–406. 10.1007/s10265-011-0459-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanski D. F., Małolepszy A., Stougaard J., Andersen S. U. (2012). Genome-wide LORE1 retrotransposon mutagenesis and high-throughput insertion detection in Lotus japonicus. Plant J. 69, 731-741. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04827.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandecasteele C., Teulat-Merah B., Morère-Le Paven M.-C., Leprince O., Ly Vu B., Viau L., et al. (2011). Quantitative trait loci analysis reveals a correlation between the ratio of sucrose/raffinose family oligosaccharides and seed vigour in Medicago truncatula. Plant Cell Environ. 34, 1473–1487. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02346.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn J. N., Nelson R. L., Song Q., Cregan P. B., Li Z. (2014). The genetic architecture of seed composition in soybean is refined by genome-wide association scans across multiple populations. G3 Bethesda 4, 2283–2294. 10.1534/g3.114.013433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdier J., Torres-Jerez I., Wang M., Andriankaja A., Allen S. N., He J., et al. (2013). Establishment of the Lotus japonicus Gene Expression Atlas (LjGEA) and its use to explore legume seed maturation. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 74, 351–362. 10.1111/tpj.12119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisin A.-S., Guéguen J., Huyghe C., Jeuffroy M.-H., Magrini M.-B., Meynard J.-M., et al. (2014). Legumes for feed, food, biomaterials and bioenergy in Europe: a review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 34, 361–380 10.1007/s13593-013-0189-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi T., Oh H., Kawaguchi M., Harada K., Sato S., Ikeda H., et al. (2014). Polymorphisms of E1 and GIGANTEA in wild populations of Lotus japonicus. J. Plant Res. 127, 651–660. 10.1007/s10265-014-0649-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z., Tan R., Yuan J., Bales C., Du W., Zhang S., et al. (2014). Genome-wide association mapping of quantitative resistance to sudden death syndrome in soybean. BMC Genomics 15:809. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S., Gao M., Xu C., Gao J., Deshpande S., Lin S., et al. (2008). Alfalfa benefits from Medicago truncatula: the RCT1 gene from M. truncatula confers broad-spectrum resistance to anthracnose in alfalfa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 12164–12169. 10.1073/pnas.0802518105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano K., Yoshida S., Mueller J., Singh S., Banba M., Vickers K., et al. (2008). CYCLOPS, a mediator of symbiotic intracellular accommodation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 20540–20545. 10.1073/pnas.0806858105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder J. B., Stanton-Geddes J., Zhou P., Briskine R., Young N. D., Tiffin P. (2014). Genomic signature of adaptation to climate in Medicago truncatula. Genetics 196, 1263–1275. 10.1534/genetics.113.159319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young N. D., Debelle F., Oldroyd G. E. D., Geurts R., Cannon S. B., Udvardi M. K., et al. (2011). The medicago genome provides insight into the evolution of rhizobial symbioses. Nature 480, 520–524. 10.1038/nature10625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Song H., Cheng H., Hao D., Wang H., Kan G., et al. (2014). The acid phosphatase-encoding gene GmACP1 contributes to soybean tolerance to low-phosphorus stress. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004061. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H., Choi H. K., Cook D. R., Shoemaker R. C. (2005). Bridging model and crop legumes through comparative genomics. Plant Physiol. 137, 1189–1196. 10.1104/pp.104.058891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]