Abstract

The past decade has seen human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing emerge as a remarkably popular test for the diagnostic work-up of coeliac disease with high patient acceptance. Although limited in its positive predictive value for coeliac disease, the strong disease association with specific HLA genes imparts exceptional negative predictive value to HLA typing, enabling a negative result to exclude coeliac disease confidently. In response to mounting evidence that the clinical use and interpretation of HLA typing often deviates from best practice, this article outlines an evidence-based approach to guide clinically appropriate use of HLA typing, and establishes a reporting template for pathology providers to improve communication of results.

Keywords: coeliac disease, diagnostics, HLA typing

Background

Coeliac disease (CD) has risen to prominence in clinical medicine. After many years as a virtual orphan disease, unclear whether it should be embraced as an autoimmune disease or food intolerance, Anderson and Mackay recently described it as a ‘singularly compelling model’ of autoimmunity with a particularly strong association to specific human leukocyte antigens (HLA).1 Today, the diagnostic utility of HLA-DQ genotyping in CD serves as an important example of the fundamental discovery by Zinkernagel and Doherty that T cells recognise antigen in combination with major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins.2 Here we discuss the scientific basis and clinical utility of HLA-DQ genetics in CD.

CD provides an excellent example of the potential benefits of incorporating genetic testing in patient management. Total requests for HLA DR/DQ/DP typing have increased more than 10-fold from 2003 (2826 services) to 2014 (32 039 services) in Australia (Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) item #71151). Assuming tissue typing for other indications (typically transplantation) have remained relatively stable, this rise is largely attributable to testing for CD. Despite its frequent use, appropriate utilisation of HLA typing for CD in Australia and New Zealand has not been formally studied. Anecdotal feedback from patients, general practitioners, physicians, dietitians and members of national patient advocacy and support groups (Coeliac Australia and Coeliac New Zealand) have raised several apparently common problems with the utilisation of HLA testing in clinical practice. These include: (i) HLA testing for inappropriate clinical situations; (ii) overly complicated or ambiguous reporting of HLA results; and (iii) inappropriate medical decisions based on HLA typing results. For instance, reports of patients commenced on gluten-free diets on the basis of positive genetic susceptibility to CD alone.

To address these shortcomings, we undertook a review of the literature and consensus statements3–9 to develop a practical guideline with an emphasis on relevance for Australian and New Zealand clinical practice (summarised in Table 1). We hope this will direct more appropriate use of this important resource and provide consistency in reporting of HLA results to optimise patient care.

Table 1.

Summary of recommendations

|

The critical importance of HLA genes for the development of CD

CD is a chronic, gluten-dependent, autoimmune enteropathy.10 The clinical presentation can include persistent or unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhoea, abdominal pain or distension, fatigue, weight loss, failure to thrive and iron-deficiency anaemia.6 Estimates of CD prevalence in Australia indicate that 1 in 60 females and 1 in 80 males are affected11 and in New Zealand 1 in 82 adults.12

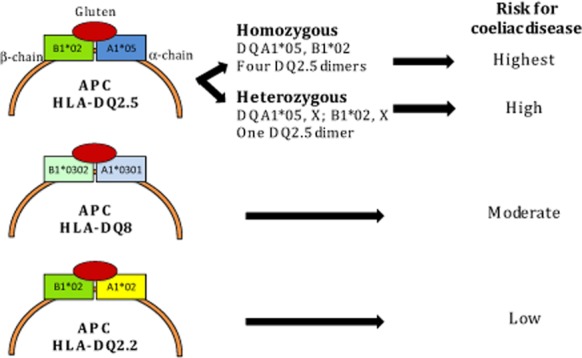

CD development is dependent on the presence of key genes that orchestrate the immunological response to dietary gluten.13 The major susceptibility genes for CD are specific HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DQB1 alleles located within the HLA region of chromosome 6p. These alleles encode α- and β-chains that form the DQ αβ-heterodimer protein (Fig. 1). One set of alleles is inherited from each parent and the sets of alleles are both expressed (co-dominant expression), meaning there are potentially two different DQA1 and two different DQB1 alleles available to form αβ-heterodimers. The DQ heterodimer resides on the surface of specialised antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and facilitates interactions between gluten peptides and T cells.2,13 The structural basis for this interaction has been elucidated by Australian, European and US researchers.14–17 Understanding this interaction and the repertoire of gluten peptides recognised by CD4+ T cells in vivo provides the basis for development of personalised medicine for patients with CD.18–21

Figure 1.

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotype and risk for coeliac disease (CD). HLA-DQ2.5, encoded by the DQA1*05 (α-chain) and DQB1*02 (β-chain) alleles, is associated with the highest risk for CD, especially when two copies of DQB1*02 allele are inherited (DQ2.5 homozygous). HLA-DQ8, encoded by DQA1*03 and DQB1*03:02, imparts moderate risk. The low risk HLA-DQ2 variant, HLA-DQ2.2, is encoded by the DQA1*02 and DQB1*02 alleles. HLA DQA1*05 without DQB1*02 (frequently observed as HLA-DQ7) appears to confer extremely low risk, but there is a paucity of data (not shown). APC, antigen presenting cell; X, any allele other than DQA1*05, DQB1*02 or DQB1*03:02.

Most CD patients (∼90%) possess the genotype HLA-DQ2.5 (previously simplified to HLA-DQ2), encoded by HLA-DQA1*05 and HLA-DQB1*02 alleles, which can be inherited in linkage on the same (cis) or a different (trans) chromosome (Fig. 1).22 Of the CD patients who do not have HLA-DQ2.5, approximately half possess HLA-DQ8, encoded by DQB1*03:02 and DQA1*03 alleles.22 The other combinations associated with CD are one ‘half’ of the HLA-DQ2.5 genotype, most commonly DQB1*02 (without DQA1*05), typically observed in linkage disequilibrium with DQA1*02 and termed HLA-DQ2.2. The remaining ‘half’ of HLA-DQ2.5, DQA1*05 (without DQB1*02) has been infrequently associated with CD, and the risk conferred for CD, if present at all, appears to be very low.22,23 This genotype is typically observed as HLA-DQ7 (DQA1*05 and DQB1*03:01) but as HLA-DQ7 can be represented by other DQA1 and DQB1 allele combinations, the term HLA-DQ7 is best avoided and HLA-DQA1*05 used instead.

Prevalence of the HLA susceptibility alleles in CD and the general population

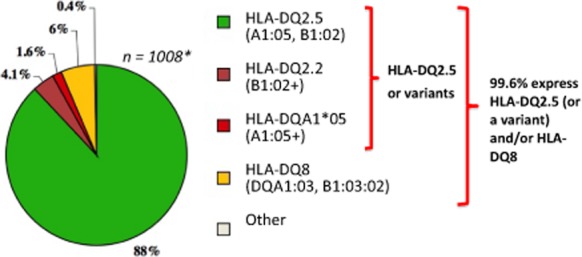

A major European consortium study established that 88% of people with CD expressed HLA-DQ2.5 (with or without HLA-DQ8), 6% HLA-DQ8 (without HLA-DQ2.5) and 5.6% one half of the HLA-DQ2.5 susceptibility heterodimer (4% DQB1*02 + and 1.6% DQA1*05+) (Fig. 2).22 Thus, one or a combination of HLA-DQ2.5, HLA-DQ8 or one half of the HLA-DQ2 susceptibility heterodimer is seen in the almost all (99.6%) patients with CD diagnosed according to expert guidelines.22,24 Similarly, in an Australian cohort of 356 patients with a medical diagnosis of CD, at least 99.7% possessed HLA-DQ2.5 (n = 325; 91.3%), HLA-DQ8 (n = 19; 5.3%) or HLA-DQ2.2 (n = 7; 2.0%).11 Clinical review of the five patients (1.4%) who lacked HLA-DQ2.5, HLA-DQ8 and HLA-DQ2.2 led to the diagnosis of CD being excluded in four: Crohn disease was diagnosed in two patients (one who was DQA1*05+) and one was diagnosed with common variable immunodeficiency; the remaining patient (who was DQA1*05+) declined re-evaluation.

Figure 2.

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotypes associated with coeliac disease (CD). 99.6% of 1008 patients with coeliac disease from Finland, France, Italy, Norway, Sweden and the UK expressed HLA-DQ2.5, a variant of HLA-DQ2.5 and/or HLA-DQ8. Similar proportions have been confirmed in Australia.11 This exceptionally strong HLA association imparts high negative predictive value for CD when these genotypes are absent. Notably, the high prevalence of these susceptibility genes in the general population (∼30–50%) renders HLA typing unhelpful as a stand-alone diagnostic for CD due to poor positive predictive value for CD. Green: HLA-DQ2.5 (A1:05, B1:02); Brown: HLA-DQ2.2 (B1:02+); Red: HLA-DQA1*05 (A1:05+); Yellow: HLA-DQ8 (DQA1:03, B1:03:02). HLA-DQ2.5 and variants are represented by green, brown and red. *Karell et al.22

The HLA susceptibility genes are not unique to CD and are also found in up to 65% of first-degree relatives (FDR) of patients with CD and over 90% of Australian type 1 diabetics, putting these groups at increased risk of developing CD.3,25 Approximately 30–40% of individuals in the Western population express at least one of these CD HLA susceptibility genes; however, the frequency is population dependent. It has been reported as high as 56% in Victoria.11 In this Australian study, approximately 25% of the community sample expressed HLA-DQ2.5 and 31% expressed HLA-DQ8 or HLA-DQ2.2 (patients with HLA-DQA1*05 are not represented). If genetic susceptibility conferred by DQA1*05 truly exists, this would increase the population susceptibility for CD by 10–35%.26 Notably, the high community prevalence of the CD HLA susceptibility alleles means HLA testing has limited positive predictive value (PPV) for CD. In one study, the PPV of HLA-DQ2.5 was 3.4% at the general population level (CD prevalence at 1%) and 28% in a ‘high-risk’ population (CD prevalence at 10%).27

The role of HLA and non-HLA genes and the environment

A variety of genes and environmental influences is critical in CD development.13 While HLA genes are essential for CD development and contribute approximately 35% of the heritable risk, genome-wide association studies implicate at least 41 other loci, most with immune modifying roles, that each contribute modestly to overall risk.28–34 The role of these non-HLA genes in CD development is poorly understood, and they are not assessed with current tests. Novel approaches that combine HLA with non-HLA genetic data have been described by Australian35 and European36,37 groups and may improve risk stratification of CD, but their clinical utility is yet to be determined.

The significance of the HLA-DQ2.5 gene dose

A strong HLA-DQ2.5 ‘gene dose’ effect exists.38,39 An individual who is HLA-DQ2.5 homozygous will only form DQ2.5 α and β dimers on the APC surface whereas in a HLA-DQ2.5 heterozygous individual these may represent as little as 25% of the total dimers formed. As a result, gluten presented by HLA-DQ2.5 homozygous APCs can induce at least a fourfold higher T-cell response compared with gluten presented by HLA-DQ2.5 heterozygous APCs.39

The gene dose effect has implications on CD development and disease phenotype. HLA-DQ2.5 homozygosity confers the greatest risk for CD development; in the USA and Europe, the risk is approximately 2.5 and 5 times that conferred by HLA-DQ2.5 heterozygosity and lower risk HLA groups respectively.40 In an Italian study following 832 newborns with a family history of CD, at 10 years of age, the risk of CD autoimmunity (positive CD serology panel) was far higher among children who were HLA-DQ2.5 homozygous (or who had two copies of DQB1*02) than among those who were HLA-DQ2.5 heterozygous or HLA-DQ8 (38% vs 19%, P = 0.001), as was the risk of overt CD (26% vs 16%, P = 0.05).41 In this cohort, 80% of those in whom CD developed did so during the first 3 years of life.

HLA-DQ2.5 homozygosity may correlate with a more severe CD phenotype with earlier disease onset, greater villous atrophy, diarrhoea and lower haemoglobin at presentation, and a slower rate of villous healing on a gluten-free diet,42 plus a higher rate of complicated (refractory) CD.43 The importance of HLA-DQ2.5 homozygosity on clinical phenotype has been recognised in a prognostic modelling tool for CD.44

The role for HLA typing in the diagnostic work-up of CD

Traditional guidelines for the diagnosis of CD rely on demonstrating the characteristic small intestinal damage (villous atrophy), and improvement of symptoms, laboratory abnormalities and villous atrophy with exclusion of dietary gluten.24 Best practice guidelines recommend CD-specific antibody testing (serology) as the initial screening investigation for CD in symptomatic people at average risk.3–7,9 Demonstrating villous atrophy while gluten is included in the diet is then used to provide definitive confirmation of the diagnosis, and remains the ‘gold standard’.

CD serology measuring antibodies to transglutaminase IgA and deamidated gliadin peptide IgG has high sensitivity for CD, and imparts a high PPV for disease (>90%) at a general population prevalence of 1%.46,47 This contrasts with the low PPV of HLA typing and makes CD serology much better suited as a first-line screening test for CD in unselected patients. However, in patients at risk of CD, HLA typing may be useful to select those who are genetically susceptible to CD for further investigation. Updated European paediatric CD guidelines now recommend HLA typing be performed, when available, as the first-line investigation in asymptomatic at-risk children.5 If a CD HLA susceptibility genotype is present, CD serology is then recommended.

Importantly, the main clinical utility of HLA typing derives from its ability to exclude a CD diagnosis when the HLA susceptibility genes are not present. The consistently strong HLA association observed across multiple populations (Europe, North America, Australia) means that the absence of HLA-DQ2.5, HLA-DQ8, HLA-DQ2.2 and HLA-DQA1*05 allows CD to be excluded with confidence for the majority of people (>99%). Unlike CD serology and intestinal histology, genotyping is a ‘once only’ test that is not reliant on gluten consumption for accuracy and may be performed on blood or a less invasive buccal swab.

Recommendations for appropriate clinical use of HLA typing

CD HLA typing should be undertaken when indicated by a medical professional with genetic counselling provided. The clinical scenario, such as family history, the presence of other risk factors for CD and results from medical investigations, will assist in the interpretation of HLA typing results. HLA typing may be useful and appropriate in the following scenarios (Table1):

When CD serology and/or small bowel examination is inconclusive or equivocal, and the diagnosis of CD remains uncertain. HLA typing can triage patients with low positive CD serology (where the PPV for CD is relatively poor48,49), or isolated serological abnormalities.50 HLA typing can reduce unnecessary endoscopies by identifying those who have false-positive screening CD serology.11 Examples of when small bowel histology might be inconclusive include the finding of lymphocytic duodenitis (Marsh grade 1), inadequate biopsy sampling and inadequate gluten consumption or use of immunosuppressant medication at the time of assessment.

When there has been failure to improve on a gluten-free diet (‘non-responsive CD’). HLA typing may assist in excluding an incorrect diagnosis of CD that may explain failure of a clinical response to dietary gluten removal.

When a gluten-free diet has been commenced prior to serologic/histologic assessment, and the patient is unwilling or unable to undertake a prolonged oral gluten challenge required for definitive diagnosis. HLA typing can exclude CD in those who are HLA negative without the need for an oral gluten challenge.

At-risk groups who are asymptomatic but at higher risk of CD. HLA typing will identify those not at risk of CD and minimise future testing, and select those who may benefit from further CD-specific testing with serology and/or small bowel histology.5 ‘At risk’ includes the presence of another immune-mediated disease (such as type 1 diabetes, autoimmune thyroid or autoimmune liver disease) or a chromosomal disease such as Down, Turner, or William syndrome.5,6 Positive HLA susceptibility may also indicate the need for further investigation of CD in people who possess higher-risk clinical features or symptoms (higher pre-test probability of CD) irrespective of CD serology results.

Family members of individuals with confirmed CD. HLA typing can exclude those not at risk of CD from further investigations and follow-up.51,52 CD affects approximately 10% of FDR with risk greatest for siblings (monozygous twins > HLA-matched siblings > siblings > parents or children).53,54 A lower risk applies to second-degree relatives.55 HLA typing may help select FDR, especially symptomatic ones, who might benefit from gastroscopy irrespective of serology, as variable degrees of enteropathy have been reported in up to half of HLA-positive FDR who sometimes have negative CD serology.56,57 In HLA-positive FDR, periodic screening with CD serology should be considered.52 The optimal interval for screening has not been established and may depend on the specific HLA genotype and age of the individual. Some experts propose closer surveillance (e.g. every 2–3 years) of a FDR if they are under 18 years of age58,59 when undiagnosed CD could have a greater impact on growth. Likewise, more intensive CD screening (e.g. yearly) of infants at highest risk of CD (HLA-DQ2.5 homozygous) has been proposed.60

Recommendations for coeliac HLA testing methodology

Historically, HLA typing performed by serology identified the serological epitopes DQ2 and DQ8. Current technology utilising polymerase chain reaction amplification of DNA and detection of sequence polymorphism in the coding regions of the DQA1 and DQB1 genes now provides very accurate HLA genotyping. Due to the large number of new HLA alleles being reported, determining the complete HLA allele sequence is recommended to avoid ambiguous results. While a large majority of HLA alleles may not need to be considered,61 a genotyping result that has resolved all common and well-documented HLA alleles is preferred. HLA typing methods that infer HLA genotypes using non-coding sequence polymorphisms, for example single nucleotide polymorphism tagging methods, may be useful in a research setting but are not able to define HLA types at a level satisfactory for individual patient care and are therefore not currently recommended.62

Recommendations for coeliac HLA typing reporting

The results of HLA typing need to be reported in a clear and concise manner but contain adequate information to optimise clinical management. It is recommended the report contain the following information (summarised in Table2):

Table 2.

Suggested templates for reporting of coeliac HLA typing results

| (i) HLA-DQ2.5 homozygous positive result | |

|---|---|

| HLA genotyping result | |

| HLA-DQA1 | 05, 05 |

| HLA-DQB1 | 02, 02 |

| |

| (ii) HLA-DQ2.5 heterozygous positive result | |

|---|---|

| HLA genotyping result | |

| HLA-DQA1 | X, 05 |

| HLA-DQB1 | X, 02 |

| nb. In the final report, X denotes the specific allele, and for this genotype cannot be DQA1*05 or DQB1*03:02 | |

| |

| (iii) HLA-DQ2.5 and DQ8 positive result | |

|---|---|

| HLA genotyping result | |

| HLA-DQA1 | X, 05 |

| HLA-DQB1 | 02, 03:02 |

| nb. In the final report, X denotes the specific allele, and for this genotype cannot be DQA1*05. | |

| |

| (iv) HLA-DQ2.2 positive result | |

|---|---|

| HLA genotyping result | |

| HLA-DQA1 | X, 02 |

| HLA-DQB1 | X, 02 |

| nb. In the final report, X denotes the specific allele, and for this genotype cannot be DQA1*05 or DQB1*02 or DQB1*03:02 | |

| |

| (v) HLA-DQ8 positive result | |

|---|---|

| HLA genotyping result | |

| HLA-DQA1 | X, X |

| HLA-DQB1 | Y, 03:02 |

| nb. In the final report, X denotes the specific allele, and for this genotype cannot be DQA1*05; Y represents the specific allele. | |

| |

| (vi) HLA-DQA1*05 positive result | |

|---|---|

| HLA genotyping result | |

| HLA-DQA1 | X, 05 |

| HLA-DQB1 | X, X |

| nb. In the final report, X denotes the specific allele, and for this genotype cannot be DQB1*02 or DQB1*03:02. | |

| |

| (vii) HLA-DQ2 and DQ8 negative result | |

|---|---|

| HLA genotyping result | |

| HLA-DQA1 | X, X |

| HLA-DQB1 | X, X |

| nb. In the final report, X denotes the specific allele, and for this genotype cannot be DQA1*05 or DQB1*02 or DQB1*03:02. | |

| |

HLA, human leukocyte antigen.

The presence or absence of all currently recognised at-risk alleles (DQB1*02, HLA-DQA1*05 and DQB1*03:02) and interpretation of the HLA genotype as HLA-DQ2.5, HLA-DQ2.2, HLA-DQ8 or HLA-DQA1*05. A complete DQA1 and DQB1 genotype is preferred to define HLA-DQ2.5 zygosity status.

A simple binary summary statement, clearly highlighted, on whether genetic susceptibility is detected, for example ‘The observed genotype is associated with genetic susceptibility for CD’ (HLA-DQ2.5, -DQ2.5/8, -DQ8, -DQ2.2 or -DQA1*05) or not detected, for example ‘The observed genotype is not associated with genetic susceptibility for CD’ (HLA-DQ2 and DQ8 negative).

A comment to highlight that a negative result can assist in the exclusion of CD. For instance, ‘The absence of HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 may serve to exclude a diagnosis of CD (likelihood of CD <1%)’.

A comment to highlight that HLA typing is not diagnostic in isolation. For instance, ‘The presence of an at-risk genotype does not confer a diagnosis of CD and has limited PPV for CD. Supportive evidence from coeliac serology and small intestinal histology is necessary for the diagnosis of CD’.

A comment on relative risk (RR) for CD based on HLA type. Until Australasian data are published, RR estimates should be provided in qualitative terms. For instance, ‘HLA-DQ2.5 homozygosity is associated with the highest genetic risk for CD’.

While the provision of RR information for CD based on HLA genotype is the subject of debate, it is clear that expressing the result as a simple binary ‘risk present’ or ‘risk absent’ fails to communicate the large differences in risk for CD conferred by each genotype, for example, HLA-DQ2.5 (high) compared with DQA1*05 (very low).63 Risk for CD generally follows the gradient HLA-DQ2 homozygous (highest) > HLA-DQ2 heterozygous or HLA-DQ2/DQ8 > HLA-DQ8 > HLA-DQ2.2 > HLA-DQA1*05 (lowest).64–66 An Italian case–control study64 estimated the absolute risk for CD at 1:10 (HLA-DQ2 homozygous), 1:35 (HLA-DQ2 heterozygous), 1:89 (HLA-DQ8), 1:210 (HLA-DQ2.2) and 1:1842 (HLA-DQA1*05). HLA-DQ2 homozygosity encompasses both DQ2.5/DQ2.5 and DQ2.5/DQ2.2, with the RR for CD in one large dataset37 highest in the former (8.4 vs 6.6). Notably, risk values will be population specific and dependent on diagnosed and undiagnosed CD prevalence and HLA frequency. Australasian data have not been published.

Arguments against providing risk estimates is that clinical management may not be changed and risk can be misinterpreted by the busy clinician as meaning disease likelihood. However, especially in light of emerging prospective data,40,41,67,68 modification of clinical management based on HLA type is becoming more likely, for example more intensive CD screening of children who are at highest genetic risk (HLA-DQ2 homozygous) for CD.60 Therefore, on balance, provision of RR information is likely to enhance clinical risk stratification of CD, but must be communicated appropriately. To avoid misinterpretation of RR, it is important to communicate that the presence of an at-risk genotype does not confer a diagnosis and has low PPV for CD, irrespective of the HLA genotype identified.

Conclusion

HLA typing for the work-up of CD is increasing, underscoring the importance of clinical guidelines to ensure its appropriate use and interpretation. Patients have enthusiastically embraced this technology, and the rise of HLA testing may be in part driven by community demand. The current popularity of wheat-free or gluten-free diets69 has meant that many people seeking a diagnosis of CD but unwilling to resume gluten consumption to enable traditional testing are being HLA typed instead. The increase may be further supported by new guidelines recommending HLA typing as a first-line test in asymptomatic individuals at risk of CD in order to select those for subsequent CD serology.5

Properly employed, HLA testing in the work-up of CD is a powerful and cost-effective tool (MBS fee $118.85) that can improve patient management by avoiding additional potentially invasive and costly investigation (gastroscopy ∼$750–1000).11 It can have a profound impact on patient management by reversing incorrect diagnoses of CD. We hope that standardised reporting of HLA results will improve clarity and patient management.

Further local information on the risk for CD imparted by each HLA type, particularly the rarer genotypes such as HLA-DQA1*05, is required. With provisional Australian data to support the cost-effective use of HLA typing when screening average-risk individuals,11 further prospective Australian and New Zealand data are required to support the clinical utility and cost-effectiveness of HLA typing and develop best practice Australasian guidelines.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank The Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia Quality Assurance Program (RCPAQAP) panel for their helpful feedback regarding HLA reporting guidelines and Dr Robert Anderson of the Medical Advisory Committee, Coeliac Australia and ImmusanT Inc., USA for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful suggestions.

Glossary

- APC

antigen presenting cell

- CD

coeliac disease

- FDR

first-degree relatives

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- PPV

positive predictive value

- RR

relative risk

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

References

- 1.Anderson WH, Mackay IR. Gut reactions – from celiac affection to autoimmune model. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:6–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1405192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zinkernagel RM, Doherty PC. MHC-restricted cytotoxic T cells: studies on the biological role of polymorphic major transplantation antigens determining T-cell restriction-specificity, function, and responsiveness. Adv Immunol. 1979;27:51–177. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60262-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rostom A, Murray JA, Kagnoff MF. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1981–2002. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill ID, Dirks MH, Liptak GS, Colletti RB, Fasano A, Guandalini S, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease in children: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;40:1–19. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabo IR, Mearin ML, Phillips A, Shamir R, et al. European society for pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:136–160. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31821a23d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones HJ, Warner JT. NICE clinical guideline 86. Coeliac disease: recognition and assessment of coeliac disease. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:312–313. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.173849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jenkins HR, Murch SH, Beattie RM. Coeliac disease working group of british society of paediatric gastroenterology H, nutrition. Diagnosing coeliac disease. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:393–394. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-301198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, Calderwood AH, Murray JA. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:656–676. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.79. , quiz 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ludvigsson JF, Bai JC, Biagi F, Card TR, Ciacci C, Ciclitira PJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease: guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut. 2014;63:1210–1228. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ludvigsson JF, Leffler DA, Bai JC, Biagi F, Fasano A, Green PHR, et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut. 2013;62:43–52. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson RP, Henry MJ, Taylor R, Duncan EL, Danoy P, Costa MJ, et al. A novel serogenetic approach determines the community prevalence of celiac disease and informs improved diagnostic pathways. BMC Med. 2013;11:188. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook HB, Burt MJ, Collett JA, Whitehead MR, Frampton CM, Chapman BA. Adult coeliac disease: prevalence and clinical significance. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:1032–1036. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abadie V, Sollid LM, Barreiro LB, Jabri B. Integration of genetic and immunological insights into a model of celiac disease pathogenesis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:493–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-040210-092915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petersen J, Montserrat V, Mujico JR, Loh KL, Beringer DX, van Lummel M, et al. T-cell receptor recognition of HLA-DQ2-gliadin complexes associated with celiac disease. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:480–488. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broughton SE, Petersen J, Theodossis A, Scally SW, Loh KL, Thompson A, et al. Biased T cell receptor usage directed against human leukocyte antigen DQ8-restricted gliadin peptides is associated with celiac disease. Immunity. 2012;37:611–621. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henderson KN, Tye-Din JA, Reid HH, Chen Z, Borg NA, Beissbarth T, et al. A structural and immunological basis for the role of human leukocyte antigen DQ8 in celiac disease. Immunity. 2007;27:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim CY, Quarsten H, Bergseng E, Khosla C, Sollid LM. Structural basis for HLA-DQ2-mediated presentation of gluten epitopes in celiac disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4175–4179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306885101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ontiveros N, Tye-Din JA, Hardy MY, Anderson RP. Ex vivo whole blood secretion of interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) and IFN-gamma-inducible protein-10 (IP-10) measured by ELISA are as sensitive as IFN-gamma ELISpot for the detection of gluten-reactive T cells in HLA-DQ2.5 + associated celiac disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175:305–315. doi: 10.1111/cei.12232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson RP, Jabri B. Vaccine against autoimmune disease: antigen-specific immunotherapy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25:410–417. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tye-Din JA, Stewart JA, Dromey JA, Beissbarth T, van Heel DA, Tatham A, et al. Comprehensive, quantitative mapping of T cell epitopes in gluten in celiac disease. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:41ra51. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson RP, Degano P, Godkin AJ, Jewell DP, Hill AV. In vivo antigen challenge in celiac disease identifies a single transglutaminase-modified peptide as the dominant A-gliadin T-cell epitope. Nat Med. 2000;6:337–342. doi: 10.1038/73200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karell K, Louka AS, Moodie SJ, Ascher H, Clot F, Greco L, et al. HLA types in celiac disease patients not carrying the DQA1*05-DQB1*02 (DQ2) heterodimer: results from the European Genetics Cluster on Celiac Disease. Hum Immunol. 2003;64:469–477. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(03)00027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sacchetti L, Calcagno G, Ferrajolo A, Sarrantonio C, Troncone R, Micillo M, et al. Discrimination between celiac and other gastrointestinal disorders in childhood by rapid human lymphocyte antigen typing. Clin Chem. 1998;44:1755–1757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walker-Smith J, Guandalini S, Schmitz J, Shmerling D, Visakorpi J. Revised criteria for diagnosis of coeliac disease. Report of working group of European society of paediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65:909–911. doi: 10.1136/adc.65.8.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doolan A, Donaghue K, Fairchild J, Wong M, Williams AJ. Use of HLA typing in diagnosing celiac disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:806–809. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.4.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koskinen L, Romanos J, Kaukinen K, Mustalahti K, Korponay-Szabo I, Barisani D, et al. Cost-effective HLA typing with tagging SNPs predicts celiac disease risk haplotypes in the Finnish, Hungarian, and Italian populations. Immunogenetics. 2009;61:247–256. doi: 10.1007/s00251-009-0361-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sollid LM, Lie BA. Celiac disease genetics: current concepts and practical applications. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:843–851. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dubois PC, Trynka G, Franke L, Hunt KA, Romanos J, Curtotti A, et al. Multiple common variants for celiac disease influencing immune gene expression. Nat Genet. 2010;42:295–302. doi: 10.1038/ng.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunt KA, Zhernakova A, Turner G, Heap GA, Franke L, Bruinenberg M, et al. Newly identified genetic risk variants for celiac disease related to the immune response. Nat Genet. 2008;40:395–402. doi: 10.1038/ng.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahn R, Ding YC, Murray J, Fasano A, Green PH, Neuhausen SL, et al. Association analysis of the extended MHC region in celiac disease implicates multiple independent susceptibility loci. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhernakova A, Stahl EA, Trynka G, Raychaudhuri S, Festen EA, Franke L, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in celiac disease and rheumatoid arthritis identifies fourteen non-HLA shared loci. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trynka G, Hunt KA, Bockett NA, Romanos J, Mistry V, Szperl A, et al. Dense genotyping identifies and localizes multiple common and rare variant association signals in celiac disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1193–1201. doi: 10.1038/ng.998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Festen EA, Goyette P, Green T, Boucher G, Beauchamp C, Trynka G, et al. A meta-analysis of genome-wide association scans identifies IL18RAP, PTPN2, TAGAP, and PUS10 as shared risk loci for Crohn's disease and celiac disease. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garner C, Ahn R, Ding YC, Steele L, Stoven S, Green PH, et al. Genome-wide association study of celiac disease in North America confirms FRMD4B as new celiac locus. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e101428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abraham G, Tye-Din JA, Bhalala OG, Kowalczyk A, Zobel J, Inouye M. Accurate and robust genomic prediction of celiac disease using statistical learning. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romanos J, Rosen A, Kumar V, Trynka G, Franke L, Szperl A, et al. Improving coeliac disease risk prediction by testing non-HLA variants additional to HLA variants. Gut. 2014;63:415–422. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romanos J, van Diemen CC, Nolte IM, Trynka G, Zhernakova A, Fu J, et al. Analysis of HLA and non-HLA alleles can identify individuals at high risk for celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:834–840. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.040. , 40.e1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koning F. Celiac disease: caught between a rock and a hard place. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1294–1301. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vader W, Stepniak D, Kooy Y, Mearin L, Thompson A, van Rood JJ, et al. The HLA-DQ2 gene dose effect in celiac disease is directly related to the magnitude and breadth of gluten-specific T cell responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12390–12395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135229100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu E, Lee HS, Aronsson CA, Hagopian WA, Koletzko S, Rewers MJ, et al. Risk of pediatric celiac disease according to HLA haplotype and country. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:42–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lionetti E, Castellaneta S, Francavilla R, Pulvirenti A, Tonutti E, Amarri S, et al. Introduction of gluten, HLA status, and the risk of celiac disease in children. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1295–1303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karinen H, Karkkainen P, Pihlajamaki J, Janatuinen E, Heikkinen M, Julkunen R, et al. Gene dose effect of the DQB1*0201 allele contributes to severity of coeliac disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:191–199. doi: 10.1080/00365520500206277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Toma A, Goerres MS, Meijer JW, Pena AS, Crusius JB, Mulder CJ. Human leukocyte antigen-DQ2 homozygosity and the development of refractory celiac disease and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:315–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Biagi F, Schiepatti A, Malamut G, Marchese A, Cellier C, Bakker SF, et al. PROgnosticating COeliac patieNts SUrvivaL: the PROCONSUL score. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e84163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hill PG, Forsyth JM, Semeraro D, Holmes GK. IgA antibodies to human tissue transglutaminase: audit of routine practice confirms high diagnostic accuracy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:1078–1082. doi: 10.1080/00365520410008051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hill ID. What are the sensitivity and specificity of serologic tests for celiac disease? Do sensitivity and specificity vary in different populations? Gastroenterology. 2005;128:S25–32. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hill PG, Holmes GK. Coeliac disease: a biopsy is not always necessary for diagnosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:572–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donaldson MR, Book LS, Leiferman KM, Zone JJ, Neuhausen SL. Strongly positive tissue transglutaminase antibodies are associated with Marsh 3 histopathology in adult and pediatric celiac disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:256–260. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31802e70b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wakim-Fleming J, Pagadala MR, Lemyre MS, Lopez R, Kumaravel A, Carey WD, et al. Diagnosis of celiac disease in adults based on serology test results, without small-bowel biopsy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:511–516. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chang M, Green PH. Genetic testing before serologic screening in relatives of patients with celiac disease as a cost containment method. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:43–50. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318187311d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karinen H, Karkkainen P, Pihlajamaki J, Janatuinen E, Heikkinen M, Julkunen R, et al. HLA genotyping is useful in the evaluation of the risk for coeliac disease in the 1st-degree relatives of patients with coeliac disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1299–1304. doi: 10.1080/00365520600684548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rubio-Tapia A, Van Dyke CT, Lahr BD, Zinsmeister AR, El-Youssef M, Moore SB, et al. Predictors of family risk for celiac disease: a population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:983–987. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hadithi M, von Blomberg BM, Crusius JB, Bloemena E, Kostense PJ, Meijer JW, et al. Accuracy of serologic tests and HLA-DQ typing for diagnosing celiac disease. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:294–302. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-5-200709040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fasano A, Berti I, Gerarduzzi T, Not T, Colletti RB, Drago S, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study.[see comment] Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:286–292. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vaquero L, Caminero A, Nunez A, Hernando M, Iglesias C, Casqueiro J, et al. Coeliac disease screening in first-degree relatives on the basis of biopsy and genetic risk. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:263–267. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Esteve M, Rosinach M, Fernandez-Banares F, Farre C, Salas A, Alsina M, et al. Spectrum of gluten-sensitive enteropathy in first-degree relatives of patients with coeliac disease: clinical relevance of lymphocytic enteritis. Gut. 2006;55:1739–1745. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.095299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Biagi F, Corazza GR. First-degree relatives of celiac patients: are they at an increased risk of developing celiac disease? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:3–4. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31818ca609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bonamico M, Ferri M, Mariani P, Nenna R, Thanasi E, Luparia RP, et al. Serologic and genetic markers of celiac disease: a sequential study in the screening of first degree relatives. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:150–154. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000189337.08139.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leonard MM, Serena G, Sturgeon C, Fasano A. Genetics and celiac disease: the importance of screening. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9:209–215. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2014.945915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mack SJ, Cano P, Hollenbach JA, He J, Hurley CK, Middleton D, et al. Common and well-documented HLA alleles: 2012 update to the CWD catalogue. Tissue Antigens. 2013;81:194–203. doi: 10.1111/tan.12093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Varney MD, Castley AS, Haimila K. Saavalainen P. Methods for diagnostic HLA typing in disease association and drug hypersensitivity. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;882:27–46. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-842-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Megiorni F, Pizzuti A. HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DQB1 in celiac disease predisposition: practical implications of the HLA molecular typing. J Biomed Sci. 2012;19:88–92. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-19-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Megiorni F, Mora B, Bonamico M, Barbato M, Nenna R, Maiella G, et al. HLA-DQ and risk gradient for celiac disease. Hum Immunol. 2009;70:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bourgey M, Calcagno G, Tinto N, Gennarelli D, Margaritte-Jeannin P, Greco L, et al. HLA related genetic risk for coeliac disease. Gut. 2007;56:1054–1059. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.108530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Margaritte-Jeannin P, Babron MC, Bourgey M, Louka AS, Clot F, Percopo S, et al. HLA-DQ relative risks for coeliac disease in European populations: a study of the European genetics cluster on coeliac disease. Tissue Antigens. 2004;63:562–567. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-2815.2004.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vriezinga SL, Auricchio R, Bravi E, Castillejo G, Chmielewska A, Crespo Escobar P, et al. Randomized feeding intervention in infants at high risk for celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1304–1315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Murray JA, Moore SB, Van Dyke CT, Lahr BD, Dierkhising RA, Zinsmeister AR, et al. HLA DQ gene dosage and risk and severity of celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1406–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Golley S, Corsini N, Topping D, Morell M, Mohr P. Motivations for avoiding wheat consumption in Australia: results from a population survey. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18:490–499. doi: 10.1017/S1368980014000652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]