Despite the advantages of electronic health records, concerns have been raised about the amount of computer time spent documenting care1 and its adverse effects on the physician-patient relationship. Using scribes to reduce physician documentation time has resulted in improved satisfaction among urologists2 and increased productivity among Emergency Department physicians3 and cardiologists4. Although scribes have been used in primary care,5 their effects have received little formal evaluation.

We created a new position, a Physician Partner (P2), to facilitate patient care during the office visit and tested this in two practices at an academic medical center to determine its effect upon physician efficiency and patient satisfaction.

METHODS

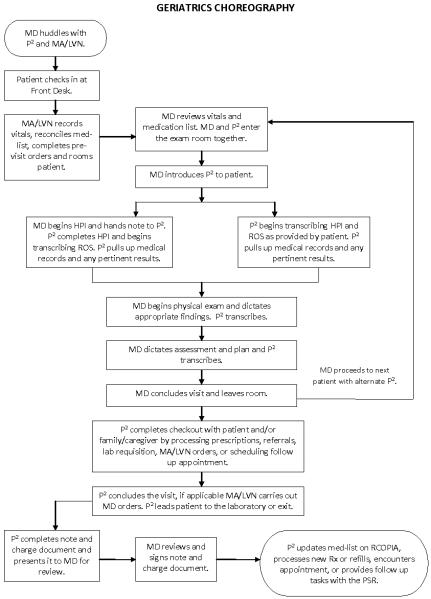

Two P2s, one bachelors level and one LVN, performed scribing and other administrative functions for 3 geriatricians and 2 general internists (IM) in a 2:1 ratio (Figure). During the study, the practices used an electronic health record (cView) that relied primarily on scanned paper outpatient notes.

Figure 1.

Choreography and Roles of Physician Partners

LVN=Licensed vocational nurse, MA=Medical assistant, MD=Physician, P2=Physician Partner, PSR=Physicians Services Representative, RCOPIA is an electronic prescribing system.

*For General Internal Medicine visits, the Physician Partner did not perform checkout functions in the room and referred patients to the front desk to perform these.

† cView EHR relies on scanned handwritten outpatient notes.

Each physician had 4-hour clinic sessions with and without P2s, thereby allowing comparisons. Efficiency was measured in a subsample of sessions by: 1) direct measurement of physician time in the examining room and 2) retrospective physician diaries of time spent before and after each session. Patient satisfaction was evaluated using questions from the CG-CAHPS survey.6

Based on time-study data, we calculated the total physician time in the examining room per session. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to compare median physician times before, during, and after each session with and without P2s. Chi-square tests were used to compare patient responses to survey questions.

RESULTS

From November 2012-June 2013, the 5 physicians in the two practices had 326 sessions that included P2s. Of these, 37 sessions (22 with and 15 without P2s) that included 289 visits had visit times monitored and 42 sessions (21 with and 21 without P2s) had physician diaries recording the amount of time they spent pre- and post-session. Patient surveys were administered to 156 patients (84 visits with and 72 visits without P2s).

In geriatrics, visits with P2s were on average 2.7 minutes shorter than visits without P2s, 18.0 (interquartile range [IQR] =14, 21) versus 20.7 (15, 26) minutes, (P=0.014). Among internists, the difference was less, 10.0 (8, 14) versus 12.0 (8, 15) minutes, (P=0.145). Per 4-hour scheduled session (Table), an estimated 152 minutes (geriatrics) and 75 minutes (internists) were saved during P2 sessions.

Table.

Median physician time (minutes) spent per 240 minute (4-hour) scheduled session

| Geriatrics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Physician Partner | P-value | |

| MD Preparation Prior to Session (IQR)* | 30 (30, 30) | 15 (10, 15) | 0.002 |

| MD time spent in examining room† | 248 (180, 312) | 216 (168, 252) | 0.014 |

| MD wrap-up post session (IQR)* | 90 (15, 120) | 15 (10, 18) | 0.012 |

| Total estimated physician time per session | 368 (225, 462) | 246 (188, 285) | |

| Internal Medicine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Physician Partner | P-value | |

| MD Preparation prior to session (IQR)* | 20 (20, 30) | 5 (5, 15) | 0.004 |

| MD time spent in examining room† | 192 (128, 240) | 160 (120, 224) | 0.145 |

| MD wrap-up post session (IQR)* | 28 (0, 43) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.005 |

| Total estimated physician time per session | 240 (148, 313) | 165 (125, 239) | |

IQR=Interquartile range

Self-reported using physician diaries for geriatrics sessions (13 with P2s, 8 without P2s) and internist sessions (8 with P2s, 13 without P2s).

Physician time per visit (based on 87 visits over 10 sessions with P2s and 63 visits over 7 sessions without P2s in geriatrics, and 78 visits over 12 sessions with P2s and 61visits over 8 sessions without P2s in internal medicine). The median was multiplied by the number of patients that the practice schedules per session. P value represents Wilcoxon rank-sum tests based on individual visits (see text).

Patients were more likely to strongly agree that the physician spent enough time with them during P2 visits (88% versus 75%, P=0.034). Although 18% were uncomfortable with P2s in the room, 79% of patients agreed that they helped the visit run smoothly.

DISCUSSION

In this study, adding personnel to perform more administrative components of office practice was associated with less pre- and post-session physician time, shorter geriatrics visits, and higher patient satisfaction. Despite these positive findings, several issues remain. First, what background and training do P2s need? We have increasingly employed bachelor’s level personnel. Training includes medical vocabulary modules, use of the electronic health record, referral and order entry, and optimizing clinic work flow. A related issue concerns scope of practice regulations. It is possible that documentation requirements of different health care systems and reimbursement regulations may impede diffusion. Finally, what are the financial implications of implementing a P2 program? Some practices have estimated that by adding 2 more visits per session, scribe programs can pay for themselves. However, because of diverse cost and reimbursement structures, the business case may vary.

Limitations of the study include the single site, small sample size, inability to measure actual time spent communicating with patients, and that only a subsample of sessions had self-reported or measured times.

In Summary, The P2S Program Provides A Potential Model To Improve Physician Efficiency And Satisfaction In The Office Setting Without Compromising Patient Satisfaction. The Program Should Be Tested In Larger Samples And Additional Settings.

Acknowledgments

We thank Niki Alejo, BA and Krisan May Soriano, LVN for their roles as Physician Partners, assisting in defining the choreography and tasks, and reviewing the manuscript; Matthew Abrishamian, BA for his role in data collection and manuscript review; and Lee Jennings, MD, MSPH for statistical assistance. They received no additional compensation for their roles in this study.

Support: This project was supported in part by the UCLA Claude Pepper Older Americans Independence Center funded by the National Institute on Aging (5P30AG028748).

REFERENCES

- 1.Jamoom E, Patel V, King J, Furukawa MF. Physician experience with electronic health record systems that meet meaningful use criteria: NAMCS Physician Workflow Survey, 2011. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2013. NCHS data brief, no 129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koshy S, Feustel PJ, Hong M, Kogan BA. Scribes in an ambulatory urology practice: patient and physician satisfaction. J Urol. 2010 Jul;184(1):258–62. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.040. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.040. Epub 2010 May 16. PubMed PMID: 20483153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arya R, Salovich DM, Ohman-Strickland P, Merlin MA. Impact of scribes on performance indicators in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2010 May;17(5):490–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00718.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00718.x. PubMed PMID: 20536801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bank AJ, Obetz C, Konrardy A, Khan A, Pillai KM, McKinley BJ, Gage RM, Turnbull MA, Kenney WO. Impact of scribes on patient interaction, productivity, and revenue in a cardiology clinic: a prospective study. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013 Aug 9;5:399–406. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S49010. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S49010. eCollection 2013. PubMed PMID: 23966799; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3745291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, Sinsky TA, Margolius D, Bodenheimer T. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013 May-Jun;11(3):272–8. doi: 10.1370/afm.1531. doi: 10.1370/afm.1531. PubMed PMID: 23690328; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3659145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) Clinician & Group Surveys (CG-CAHPS) Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ); [accessed11/30/2013]. https://www.cahps.ahrq.gov/surveys-guidance/cg/index.html [Google Scholar]