Abstract

This study examined the mental health and academic functioning of 442 4- and 5-year old children of Mexican (MA) and Dominican (DA) immigrant mothers using a cultural framework of Latino parenting. Data were collected on mothers' self-reported acculturative status, parenting practices and cultural socialization, and on children's behavioral functioning (mother- and teacher-report) and school readiness (child test). Results provide partial support for the validity of the framework in which mothers' acculturative status and socialization of respeto (a Latino cultural value of respect) and independence (a U.S. American cultural value) predict parenting practices. For both groups, English language competence was related to less socialization of respeto, and other domains of acculturative status (i.e., U.S. American/ethnic identity, and U.S. American/ethnic cultural competence) were related to more socialization of respeto and independence. Socialization of respeto was related to the use of authoritarian practices and socialization of independence was related to the use of authoritative practices. Socialization of respeto was also related to lower school readiness for DA children, whereas socialization of independence was related to higher school readiness for MA children. Independence was also related to higher teacher-rated externalizing problems for MA children. For both groups, authoritarian parenting was associated with more parent-reported internalizing and externalizing problems. The discussion focuses on ethnic subgroup differences and similarities to further understanding of Latino parenting from a cultural perspective.

Keywords: Mexican families, Dominican families, parenting, ethnic socialization, early childhood

Traditional parenting theory emphasizes demandingness/control and responsiveness/warmth as key dimensions underlying parenting styles. A robust literature documents that authoritative, authoritarian and permissive parenting styles, and the parenting practices that map onto them, are key in understanding children's developmental outcomes. Among Mexican Americans (MA), the largest and most widely studied Latino group, mothers of young children, school-age children, and adolescents have been characterized by many studies as authoritarian, hostile, controlling, and inconsistent in their approach to parenting (Cardona, Nicholson, & Fox, 2000; Florsheim, Tolan, & Gorman-Smith, 1996; Knight, Virdin, & Roosa, 1994; Parke et al., 2004; Rodriguez & Olswang, 2003; Steinberg, Lamborn, Darling, Mounts, & Dornbush, 1994; Varela et al., 2004), and by other studies as authoritative, protective, warm, and responsive (Domenech Rodríguez, Donovick, & Crowley, 2009; Gamble, Ramakumar, & Diaz, 2007; MacPhee, Fritz, & Miller-Heyl, 1996; Martinez, 1988). Very little is known about parenting among Dominican Americans (DA), although they comprise one of the largest Latino subgroups in the US (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). Based on the few studies that have focused on DA families, DA mothers are generally characterized as both highly controlling (Fracasso, Busch-Rossnagel, & Fisher, 1994; Guilamo-Ramos, Dittus, Jaccard, Johansson, Bouris, & Acosta, 2007; Planos, Zayas, & Busch-Rossnagel, 1997) and highly nurturing (Calzada & Eyberg, 2002; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2007).

Among Latino families, relations between parenting styles/practices and child development are not well understood. For example, many studies with Latino families have failed to establish an association between authoritarian or harsh/hostile parenting and child internalizing and externalizing problems (Bird et al., 2001; Calzada & Eyberg, 2002; Gonzales et al., 2011; Gorman-Smith, Tolan, Henry, & Florsheim, 2000; Hill, Bush, & Roosa, 2003; Knight et al., 1994; Lindahl & Malik, 1999; Manongdo & Garcia, 2011; Parke et al., 2004; Zimmerman, Khoury, Vega, Gil, & Warheit, 1995), challenging the notion of authoritative parenting as normative and optimal and authoritarian parenting as maladaptive. Instead, these studies suggest that the nature and effects of parenting depend on the family's cultural context (Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2009; Livas-Dlott et al., 2010).

Among immigrant Latino populations, parenting is expected to reflect the adaptation of traditional child rearing values and behaviors to U.S. contextual conditions and demands (Fuller & Garcia Coll, 2010; Reese, 2002). An emerging empirical literature shows that the process of adapting to a new culture, known as acculturation (and the parallel process of maintaining one's native culture, known as enculturation), has great potential to enhance understanding of Latino parenting (Gonzales, Knight, Morgan-Lopez, Saenz, & Sirolli, 2002; Grau, Azmitia, & Quattlebaum, 2009). Less acculturated (e.g., foreign-born, Spanish speaking) mothers tend to use authoritarian practices more than acculturated mothers, who tend to use authoritative practices (Buriel, 1993; Buriel, Mercado, Rodriguez, & Chavez, 1991; Dumka, Roosa, & Jackson, 1997; Fridrich & Flannery, 1995; Parke et al., 2004; Samaniego & Gonzales, 1999). Moreover, relative to enculturated mothers, acculturated mothers tend to embrace mainstream values such as independence over traditional values such as respeto (i.e., respect for authority; González-Ramos, Zayas, & Cohen, 1998).

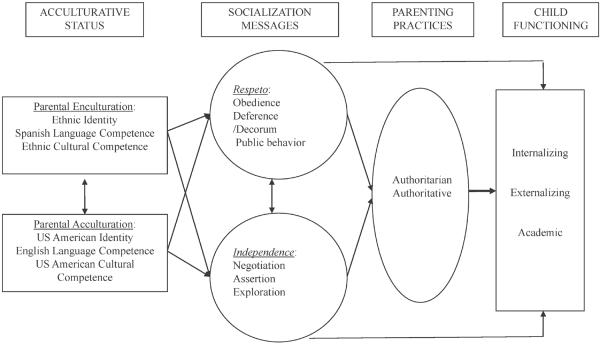

Building on these studies and with the goal of integrating cultural and developmental concepts to address some of the limitations identified in the literature, Calzada and colleagues (Calzada, Fernandez, & Cortes, 2010) proposed a framework for the study of Latino parenting. As presented in Figure 1, this framework is based on the premise that cultural values are fundamental to the child rearing goals of parents, and that parents actively seek to inculcate important values in their children through a process known as ethnic socialization and through the use of parenting practices that support their socialization goals. The framework focuses on respeto and independence as core cultural values that represent Latino versus U.S. American culture, are theoretically opposed, and are believed to influence child rearing (Calzada et al., 2010; Delgado-Gaitan, 1994; Harwood, 1992). To socialize Latino children to behave according to the Latino value of respeto, with its emphasis on obedience, deference, decorum, and public behavior, a parent may rely on the use of more authoritarian parenting practices. In contrast, socialization to the U.S. American value of independence, with its emphasis on negotiation, exploration and assertion, may prompt the use of more authoritative parenting practices. Both socialization messages and parenting practices are expected to shift in accordance with parents' acculturative status (i.e., acculturation and enculturation; Dumka et al.,1997; González-Ramos et al., 1998; Planos, Zayas & Busch–Rossnagel, 1995; Planos et al., 1997; Roosa, Morgan-Lopez, Cree, & Specter, 2002), and both are expected to predict child functioning. Calzada et al.'s framework recognizes the well-established literature based primarily on non-Latino white families documenting a robust relation between parenting practices and child development (Baumrind, 1991; McMahon & Wells, 1989; Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992), and a newly emerging literature based on Latino families suggesting that child development is associated with socialization messages (Calderón-Tena, Knight, & Carlo, 2011; Hughes, Rodriguez, Smith, Johnson, Stevenson, & Spicer, 2006; Knight, Cota, & Bernal, 1993) and parents' acculturative status (Coatsworth et al., 2002; Dumka, Gonzales, Bonds, & Millsap, 2009; Smokowski, Rose, & Bacallao, 2008).

Figure 1.

Cultural framework of Latino parenting.

The present study tested this cultural framework of Latino parenting (Calzada et al., 2010) with families of Mexican and Dominican origin living in New York City (NYC), where MAs and DAs are expected to become the largest Latino subgroups, surpassing the large and long-standing Puerto Rican community by 2020 (Center for Latin American, Caribbean and Latino Studies, 2008). The study focuses on families in Pre-Kindergarten (Pre-K) and Kindergarten (K) programs, as children embark on their formal educational experience. For many immigrant families, the start of school marks the first sustained and structured interactions with mainstream society, with implications for the ways in which the Latino and American cultures may influence parenting. As suggested by the model, we hypothesized that mothers' acculturative status would be associated with their socialization messages, and specifically that acculturation would be associated with higher levels of socialization to independence and enculturation would be associated with higher levels of socialization to respeto. In turn, we expected independence messages to be associated with authoritative parenting and respeto messages to be associated with authoritarian parenting. Finally, we expected both socialization messages and parenting practices to be associated with child functioning, though we made no predictions about the direction of those associations. To our knowledge, this is one of few empirical studies to examine parenting and culture in relation to children's internalizing, externalizing, and academic functioning among Latino families of young children, and the only one to focus on these relations in two distinct subgroups (MA and DA).

Method

Participants

Participants were 467 Mexican and Dominican families drawn from two independent multimethod longitudinal studies examining the early childhood development of Latino children. In both studies, families were recruited from Pre-K and K classrooms in NYC. All children were 4 or 5 years old at the time of enrollment into the study (Time 1), and were reassessed 12 months later (Time 2). The present study included data from Time 1 only. In Study 1 (n = 298; 52% MA), the sample was drawn from 11 Head Start centers (n = 184), 16 preschool programs in community based organizations (n = 71), two private schools (n = 22), and 14 public schools (n = 17). In Study 2 (n = 169; 53% MA), the sample was drawn exclusively from 15 public schools (that had not participated in Study 1). Given the small number of U.S.-born mothers across both studies (n = 25; 5%), only immigrant mothers were included in the present analyses (n = 442).

As shown in Table 1, MA (n = 232) and DA (n = 210) families differed on most demographic characteristics. For example, compared to DA mothers, MA mothers were more likely to be married to or living with the child's father and to have larger families. MA mothers were also younger, less likely to have graduated from high school, less likely to be working for pay, and more likely to be living in poverty. At the neighborhood level, MA families resided in 41 zip-code and 103 census-tract areas, and DA families resided in 32 zip-code and 74 census-tract areas throughout NYC. According to census 2000 data, the neighborhoods were, on average, immigrant-dense Latino neighborhoods, although there was some diversity. The neighborhoods in which the MA families lived were on average 56% pan-Latino (range = 6%–93%), 10% Mexican (range = 0%–34%), and 44% immigrant (range = 11%–78%). The neighborhoods where DA families were living were on average 71% pan-Latino (range = 5%–93%), 32% Dominican (range = 0%–57%), and 46% immigrant (range = 12%–62%).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics by Ethnic Group

| Mexican |

Dominican |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

| Child age | 4.67 (.49) | 4.73 (.52) | .20 |

| Mother's age | 30.38 (5.28) | 35.11 (6.94) | <.001 |

| Length of residence in US (in years) | 9.65 (4.37) | 12.24 (6.98) | <.001 |

| Number of household members | 5.55 (1.65) | 4.27 (1.24) | <.001 |

| % |

% |

||

| Child Gender—Male | 47.4 | 53.8 | .18 |

| Child assessment in Spanish | 86.9 | 60.5 | <.001 |

| Mother assessment in Spanish | 99.6 | 93.3 | <.001 |

| Foreign-born—Child | 3.0 | 12.4 | <.001 |

| Two-parent household | 89.7 | 63.0 | <.001 |

| Mother Education (% <HS) | 60.3 | 27.3 | <.001 |

| Mother works for pay | 19.5 | 63.6 | <.001 |

| Family poverty status | 87.4 | 70.4 | <.001 |

| % immigrant (neighborhood) | 44.2 | 46.0 | .23 |

| % Latino (neighborhood) | 56.6 | 71.1 | <.001 |

| % Dominican (neighborhood) | 11.0 | 32.1 | <.001 |

| % Mexican (neighborhood) | 9.8 | 3.1 | <.001 |

Note. T-test and chi-square analyses were used to analyze group differences. Poverty based on federal guidelines, with consideration for number of persons living in the home.

Measures

Cultural socialization

To examine socialization messages, mothers completed the Cultural Socialization of Latino Children (CSLC; Calzada, 2007), a measure that was based on Latina mothers' descriptions of the behavioral manifestations of the Latino value of respeto and the US American value of independence (Calzada et al., 2010). The measure was developed with parallel versions in Spanish and English. During measure development, all items were pilot tested with 37 Latina mothers from various countries of origin for feasibility, and modifications to language were made based on participant feedback. Universal terms were used whenever possible, and synonyms were provided for terms that vary between Latino subgroups. The respeto scale includes 20 items (e.g., “I tell my child to defer to adult wishes”) and the independence scale includes 17 items (e.g., “I encourage my child to tell me when he disagrees with me”). Mean scale scores are created, and higher scores reflect more socialization of that value. A scale of 1–7 was used in Study 1. Based on experience in administering the measure, we simplified the response options to a scale of 1–5 for Study 2. Given the change in scales, we rescaled all responses in order to have a comparable scale across studies. Mean scale scores were rescaled to 0–100 by applying the formula: (mean score −1)/(possible mean score range). Internal consistency was adequate for both scales and was similar for the MA and DA samples across both studies (α were .82 and .77 for MA, and.82 and .78 for DA, for respeto and independence, respectively). The intercorrelation between the two scales was r = .34 for MAs and .30 for DAs.

Acculturation

The Abbreviated Multidimensional Acculturation Scale (AMAS; Zea, Asner-Self, Birman, & Buki, 2003) is a self-report measure of acculturative status (i.e., acculturation, enculturation) that can be used with any ethnic group. The AMAS measures three domains: cultural competence, language competence, and identity. The 42 items are rated from 1 (not at all) to 4 (extremely well). All domains are measured for both the culture of origin (enculturation) and mainstream/“U.S. American” culture (acculturation), allowing for an examination of acculturative status as a bidimensional construct. The AMAS was developed and standardized in English and Spanish with Latino university students and community members from various countries of origin and showed adequate psychometric properties (Zea et al., 2003). Sample items include “I feel like I am part of US/MA/DR culture,” (identity) “How well do you know the history of US/MA/DR?” (cultural competence) and “How well do you speak English with strangers?” (language). Internal consistencies were high for all subscales for both groups (MA: α range .83–.96; DA: α range .88–.98).

Parenting styles

The Parenting Styles and Dimensions (PSD; Robinson, Mandleco, Olsen, & Hart, 1995) is a 32-item parent report measure of parenting practices with three orthogonal factors corresponding to Baumrind's (1995) authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive parenting style constructs. Parents respond to each item on a 5-point Likert scale anchored by 1 (never) and 5 (always). The PSD has been standardized for parents of young children, and has been used with samples of various ethnic backgrounds (Hart, Nelson, Robinson, & McNeilly-Choque, 1998), including Latina mothers from the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico (Calzada & Eyberg, 2002). Exploratory factor analyses were conducted to determine whether the authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive constructs were valid in this sample of DA and MA Latina mothers. We found a good fit for a 2-factor model of authoritative and authoritarian parenting practices. Permissive items loaded primarily on the authoritarian parenting style construct, so to be consistent with the original constructs, we excluded all of the permissive items. This decision was confirmed by the low internal consistency of the permissive construct (α = .58 and .54 for MA and DA mothers). The internal consistencies of authoritative (α = .85 and .82) and authoritarian (α = .76 and .67) parenting practices were mostly in the good to acceptable range, though it was in the questionable range for the authoritarian scale with the DA sample (George & Mallery, 2003). Given its theoretical importance and the factor analytic results that support its use with the present sample, we included the authoritarian scale in all analyses.

Child functioning

The Behavior Assessment System for Children, Parent Rating Scale and Teacher Rating Scale (BASC PRS, BASC TRS; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004) is a measure of child behavior and emotional functioning for children between the ages of 2.5 and 18 years with well-established psychometric properties. The BASC has both a parent report form (PRS) and a teacher report form (TRS). The PRS was translated into Spanish and standardized by the measure developers with a sample of 386 Latinos (specific ethnic groups not described). The Spanish language version is meant to be used with Spanish-speakers from any country of origin (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). In the present study, 93% of mothers completed the Spanish version. All sub-scales and broad domains showed adequate internal consistencies (α = .83–.93 for MA, and .84–.95 for DA), and only the broad domains of Externalizing Problems (e.g., aggression, conduct problems) and Internalizing Problems (e.g., depression, anxiety) were used in the present study.

School readiness

The Developmental Indicators for the Assessment of Learning-Third edition (DIAL-3; Mardell-Czudnowski & Goldenberg, 1998) is an individually administered test designed for the developmental screening of children between the ages of 3 and 6 years. The behaviors assessed through the DIAL-3 relate directly to successful classroom functioning during Pre-K, Kindergarten, and first grade. Specifically, the DIAL assesses motor, conceptual and language development that is considered the foundation for successful academic learning. It yields a total score ranging from 0–39 based on the three domains: motor (e.g., building, copying), concepts (e.g., naming colors, identifying body parts), and language (e.g., letters and sounds, naming actions). Higher scores indicate better school readiness. The DIAL has well-established psychometric properties and includes indicators of potential developmental delays. The abbreviated version of the DIAL-3, the Speed DIAL, is available in Spanish and English and was used in the present study (α = .84 and .81 for MA and DA).

Procedure

With the exception of recruitment site, procedures were identical in Studies 1 and 2. In Study 1, families were recruited through preschool programs serving 4–5-year-old children (e.g., Head Start programs, community-based preschool programs, elementary schools) throughout NYC between 2007 and 2009. In Study 2, families were recruited through public schools from Pre-K and K classrooms in 2010. At collaborating sites, research staff, fluent in Spanish and English, attended parent meetings and were present during daily school drop-off and pick-up times to inform parents of the study. Interested mothers were scheduled for an appointment at their child's school where they were met by a pair of bilingual research staff. One research staff interviewed the mother after obtaining her consent, while the other administered a battery of psychological tests (e.g., school readiness, language development) to the child. In Study 1, we did not have access to data regarding the eligibility (i.e., the ethnicity) of all families within a recruitment site and were unable to determine rates of recruitment. In Study 2, the recruitment rate averaged 72% (53%–94%) across the 15 schools.

Mothers who participated were asked whether they preferred Spanish or English before beginning any research activities. The majority of mothers (99% of MA and 94% of DA) chose to be interviewed in Spanish. After obtaining consent, interview questions and response choices were provided to mothers in written form (via a response booklet) and were also read aloud by research staff; mothers' oral responses were recorded. Children were tested in the language requested by their mothers, although responses in either language were accepted on all measures. Upon completing the 2-hr assessment, mothers were paid $35 for their participation and children received a book (in Spanish when available for purchase at the local bookstore, and otherwise in English) to take home. Teachers of participating children (99% of mothers consented to the collection of teacher report) were then asked to consent and complete a packet of questionnaires; teachers were paid $10 for each packet of child ratings. One hundred and forty teachers provided data for 89% (n = 207) of MA and 91% (n = 192) of DA participant children. In addition to the payments, these teacher enrollment rates reflect the consistent presence of research staff in schools, where researchers offered support to administrators and teachers. There were no differences on demographic characteristics or on study variables between children who had teacher ratings and those who did not. All of the data used in the present study were collected at Time 1.

Analytic Approach

Before conducting analyses, we examined clustering effects because about half (55%) of the teachers provided ratings on multiple students [the average number of students rated by each teacher was 2.17 (SD = 1.72)]. We calculated design effects [1 + (average group size − 1) × intraclass correlation coefficient] and followed guidelines suggested by Muthén and Satorra (1995) to determine whether traditional statistical techniques could be employed without concern for bias from the clustered nature of the sampling design. In our sample, the design effects for teacher rated variables were all less than 2.0, suggesting that traditional statistical techniques could be used. Next, we examined the distribution of all endogenous variables (i.e., those that are influenced by other study variables); each was normally distributed.

Finally, we used structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the conceptual model (see Figure 1), allowing for (a) meditational links from acculturative status to socialization messages to parenting practices to child functioning, (b) direct links from socialization messages to child functioning, and (c) variables within each domain (i.e., acculturative status, socialization, parenting, child functioning) to be correlated. The SEM model was tested using MPLUS 6 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010) and maximum likelihood estimation method (ML). To judge the closeness of fit of the hypothesized model, three indices were used as recommend by Muthén & Muthén (2010): chi square (χ2 > .05 or χ2/df ratio less than 3.0), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < .05), and comparative fit index (CFI > .95).

We first conducted multigroup SEM analyses to determine whether there were statistically significant subgroup differences in model fit. In testing the model simultaneously for MA and DA samples, multigroup SEM allowed us to compare significant paths between the two groups. In multigroup SEM, the first step is to test the nonrestricted model in the two groups by allowing all path values, means, variances, and covariances to be freely estimated. If there is evidence of fit, the next step is to examine a less restricted model by constraining path estimates to be equal in all groups, but allowing means, variances, and covariances to be free. More constraints (i.e., on means, variances, and covariances) can be imposed in subsequent steps if the more restricted model does not cause a significant decrement in model fit. If there is insufficient evidence of fit in the least restricted multigroup SEM model (in which path values, means, variances, and covariances are all freely estimated), then the SEM model is tested separately for each group (i.e., MA and DA).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations, and Table 3 presents correlations, for all study variables for each ethnic group. MA mothers reported lower levels of acculturation (U.S. identity, U.S. cultural competence, English language competence) and lower ethnic cultural competence and Spanish language competence, but similar levels of ethnic identity, relative to DA mothers. MA mothers also reported higher levels of authoritarian parenting and lower levels of authoritative parenting than DA mothers. There were no ethnic group differences on socialization messages; both MA and DA mothers reported high levels of socialization to respeto (conceptualized as a reflection of Latino culture) as well as high levels of socialization to independence (conceptualized as a reflection of U.S. culture). According to mother report, MA and DA children had similar levels of externalizing and internalizing problems, but according to teacher report, DA children had higher levels of both types of problems. Finally, MA children had significantly lower school readiness, as measured by the objective DIAL test, than DA children.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables

| Mexican (N = 232) |

Dominican (N = 210) |

t | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

| Enculturation | |||

| 1. Ethnic Identity† | 3.93 (.30) | 3.88 (.29) | 1.60 |

| 2. Ethnic Cultural Competence | 2.68 (.68) | 3.10 (.66) | −6.51*** |

| 3. Spanish Language Competence† | 3.66 (.47) | 3.80 (.35) | −3.65*** |

| Acculturation | |||

| 4. U.S. Identity | 2.05 (.83) | 2.77 (.87) | −8.97*** |

| 5. U.S. Cultural Competence | 1.59 (.47) | 2.25 (.58) | −13.10*** |

| 6. English Language Competence† | 1.75 (.49) | 2.25 (.75) | −8.14*** |

| Ethnic Socialization | |||

| 7. Respeto | 77.95 (13.87) | 79.16(14.41) | −.89 |

| 8.Independence | 85.53 (10.72) | 85.61 (9.98) | .08 |

| Parenting Practices | |||

| 9. Authoritative† | 3.94 (.65) | 4.18 (.55) | −4.14*** |

| 10. Authoritarian | 1.90 (.52) | 1.78 (.48) | 2.52* |

| Child Functioning | |||

| 11. BP-EXT | 48.95 (9.47) | 48.55 (8.78) | .46 |

| 12. BP-INT | 54.53(10.11) | 54.93 (10.62) | −.41 |

| 13. BT-EXT† | 46.89 (7.57) | 49.60 (10.32) | −3.00** |

| 14. BT-INT | 47.30 (8.44) | 49.84 (9.60) | −2.80** |

| 15. DIAL | 18.77 (7.40) | 20.34 (7.23) | −2.25* |

indicates group differed in variance.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 3.

Correlations Among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enculturation | |||||||||||||||

| 1. Eth identity | 1.00 | .17* | .11 | −.13 | −.34*** | −.21** | .18** | −.12 | .03 | .03 | .02 | .07 | .13 | .10 | −.20** |

| 2. Eth cult comp | 0.06 | 1.00 | .41*** | −.06 | .05 | −.23*** | .24*** | .22** | .20** | .04 | .04 | .09 | .21** | .06 | .06 |

| 3. Spanish comp | .20** | .33*** | 1.00 | .01 | .05 | −.03 | .30*** | .17* | .26*** | .03 | −.06 | −.05 | .15* | .05 | −.001 |

| Acculturation | |||||||||||||||

| 4. U.S. identity | −0.22** | −.11 | −.12 | 1.00 | .27*** | .11 | .12 | .18* | .09 | .03 | .02 | .06 | .03 | .09 | −.05 |

| 5. U.S. cult comp | −.03 | .24*** | .04 | .32*** | 1.00 | .65*** | −.05 | .13 | .18** | .04 | .04 | .12 | −.11 | −.01 | .16* |

| 6. English comp | −.06 | .20** | .06 | .19** | .58*** | 1.00 | −.26*** | .02 | .18** | −.01 | .04 | .09 | −.11 | −.03 | .15* |

| Socialization Messages | |||||||||||||||

| 7. Respeto | .002 | .13* | .02 | .04 | −.06 | −.23*** | 1.00 | .24*** | −.10 | .28*** | .07 | .08 | .16* | .10 | −.16* |

| 8.Independence | .14* | .22** | .20** | −.08 | .03 | −.03 | .34*** | 1.00 | .37*** | −.04 | −.05 | .13 | −.04 | .04 | −.02 |

| Parenting Practices | |||||||||||||||

| 9. Authoritative | .04 | .15* | .25*** | −.01 | .14* | .18** | .10 | .51*** | 1.00 | −.07 | −.03 | .16* | −.02 | .10 | .14* |

| 10. Authoritarian | −.07 | .06 | −.01 | .11 | −.14* | −.17* | .31*** | .07 | .03 | 1.00 | .43*** | .39*** | 22** | .25** | −.10 |

| Child Functioning | |||||||||||||||

| 11. BP-EXT | −.05 | .06 | .00 | −.01 | −.03 | −.05 | .13* | −.05 | −.05 | .42*** | 1.00 | .51*** | .36*** | .23** | −.10 |

| 12. BP-INT | −.05 | −.03 | −.11 | −.01 | −.09 | −.10 | .17** | .18** | .13* | .36*** | .59*** | 1.00 | .03 | .22** | −.03 |

| 13. BT-EXT | .09 | .06 | .05 | −.04 | .01 | −.08 | .20** | .11 | −.01 | .25*** | .34*** | .09 | 1.00 | .56*** | −.22** |

| 14. BT-INT | .01 | .05 | .01 | .02 | −.03 | −.08 | .07 | .10 | −.05 | .12 | .09 | .12 | .33*** | 1.00 | −.21** |

| 15. DIAL | .01 | −.07 | −.002 | −.07 | .13* | .15* | −.20** | .02 | .23** | −.16* | −.12 | .07 | −.11 | −.12 | 1.00 |

Note. Correlations for the Mexican sample presented below the diagonal; Correlations for the Dominican sample presented above the diagonal.

p < .05.

p < .o1.

p < .001.

Model Testing

We first tested a nonrestricted model using multigroup SEM analyses. The overall χ2 statistics showed a good fit of the non-restricted model, χ2(84) = 115.61, p = .01, RMSEA = .04 and CFI = .96. We then tested the model that constrained all parameter estimates (or path values) to be equal across groups, but that allowed free estimates for means, variances, and covariances. The model yielded a poor fit, χ2(147) = 371.30, p < .001, RMSEA = .09, CFI = .72, indicating that imposing equality constraints on the parameter estimates caused a significant decrement in model fit (Δ χ2(63) = 255.7, p < .001). This suggested that the processes in MAs and DAs were significantly different, so we conducted SEM analyses separately for the MA and DA groups.

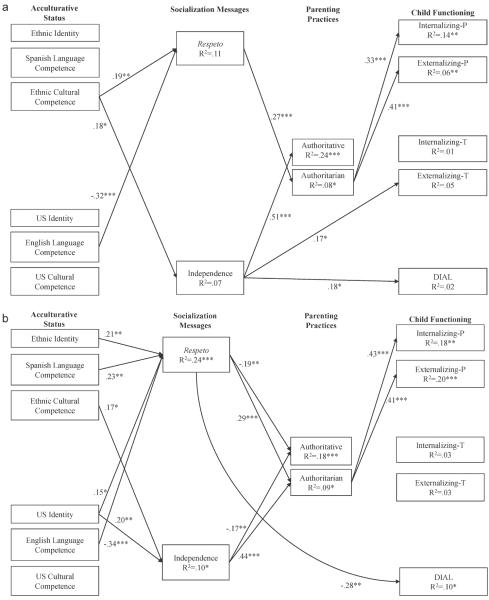

Using SEM analyses separately for each group, we found a good fit of the hypothetical model for both MAs and DAs. [MA: χ2(42) = 51.99, p = .14, RMSEA = .03 and CFI = .97 and DA: χ2(42) = 58.98, p = .04, RMSEA = .05 and CFI = .95]. Figures 2a (for MA) and 2b (for DA) present the standardized path coefficients for the significant paths and the R2 values for each endogenous variable (i.e., socialization, parenting, and child functioning).

Figure 2.

a. Standardized coefficients for the cultural framework of Latino parenting: Mexican sample. b. Standardized coefficients for the cultural framework of Latino parenting: Dominican sample. Note. Paths that did not reach significance are not shown in this figure. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

For MAs, we found that ethnic cultural competence was positively related to socialization of respeto, and that English language competence was negatively related to socialization of respeto. Unexpectedly, ethnic cultural competence was also positively related to independence. As expected, socialization to respeto was associated with more authoritarian parenting, and socialization to independence was associated with more authoritative, parenting practices. More socialization to independence was associated with better school readiness test scores and more teacher-rated externalizing problems. Finally, authoritarian parenting was associated with higher parent-rated internalizing and externalizing problems.

For DAs, ethnic identity and Spanish language competence were associated with more socialization of respeto, whereas English language competence was associated with less socialization of respeto. In addition, U.S. American identity was associated with more socialization of independence. Contrary to our hypotheses, U.S. American identity was also associated with more respeto messages, and ethnic cultural competence was associated with more independence messages. As predicted by the model, respeto was associated with more authoritarian and less authoritative, and independence was associated with more authoritative and less authoritarian parenting practices. Respeto was associated with lower levels of school readiness. Finally, authoritarian parenting was associated with higher externalizing and internalizing problems in the home (i.e., as rated by parents).

Discussion

The present study found evidence in partial support of a framework of Latino parenting (Calzada et al., 2010) that considers the influence of parents' acculturative status on their parenting and ultimately on the functioning of their young children. Findings are consistent with cultural and developmental theories and extend the empirical literature by integrating specific cultural constructs (i.e., ethnic socialization, parental acculturation, parental enculturation) into the study of Latino children as they begin formal schooling. Specifically, findings showed that Mexican and Dominican mothers' acculturative status was related to their socialization messages, which were associated with their parenting practices; socialization had a direct and indirect association with child functioning, and authoritarian but not authoritative parenting practices were also associated with child functioning.

MA and DA Parenting Practices

This study contributes to our understanding of the nature of Latino parenting by showing that MA and DA mothers of young children tend to rely more on the use of authoritative than authoritarian parenting practices, at least according to their self-report. The present study also found modest but significant differences in parenting between the two groups. Relative to DA mothers, MA mothers endorsed the use of more authoritarian and less authoritative parenting practices, perhaps related to sociodemographic background of the mothers (i.e., urban vs. rural; Greenfield, 2009). For both groups, authoritarian parenting was associated with higher levels of externalizing and internalizing problems in the home. Although interpretation of these results must be tempered with recognition of some methodological limitations (i.e., reliance on cross-sectional data), they nonetheless indicate that authoritarian parenting may be a risk factor for the mental health functioning of young MA and DA children. In spite of the well-established link between authoritarian parenting and negative child outcomes among non-Latino white families, these findings with Latino families are somewhat surprising. Past studies have found that author itarian practices have no association or even have a positive association with Latino children's functioning, suggesting that authoritarian parenting plays a protective role among families living in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods (Gorman-Smith et al., 2000; Knight et al., 1994). The present findings suggest that at very young ages (i.e., 4–5 years old), when children do not yet spend time alone in the neighborhood, authoritarian parenting—with its reliance on harsh practices—may signal the presence of coercive processes rather than protective parenting.

Socialization Messages

MA and DA mothers both reported frequent use of socialization messages to teach respeto, a traditional Latino cultural value that stresses obedience, deference and decorum. MA and DA mothers also reported an equally frequent use of socialization messages to teach independence, a traditional U.S. cultural value that stresses assertion, negotiation, and exploration. The strong emphasis on both independence and respeto implies that Latina immigrant mothers may adopt values from their receiving culture while retaining values from their culture of origin, resulting in a bicultural approach to parenting, at least within this particular domain (Delgado-Gaitan, 1994; Harwood, Schoelmerich, Schulze, & Gonzalez, 1999). Still, the socialization to independence by a sample of Latina mothers with low levels of formal education and high levels of poverty is notable given the argument that child rearing values to promote self-direction and self-sufficiency (vs. obedience and conformity) reflect higher SES at both the community and family levels (Greenfield, 2009; Foucault & Schneider, 2009). For Latina mothers living in the U.S., promoting children's independence may be adaptive given the lower rates of child rearing support and higher rates of parenting stress experienced by many immigrant parents, especially within certain ecological contexts (e.g., inner-city).

For MA children, socialization of independence was associated with more behavior problems, as rated by teachers, but also better school readiness. Perhaps children who are socialized to be assertive, to negotiate for themselves, and to explore their environment develop more sophisticated cognitive skills but also present as more disruptive as they assert themselves in the classroom. Socialization of independence was not directly associated with the functioning of DA children, but for this group, socialization of respeto was directly and negatively associated with school readiness. It is possible that the emphasis on obedience and deference rather than communication within the parent–child relationship limits young children's opportunities to develop certain preacademic skills such as problem-solving. It is not clear why the relations between socialization and child functioning were unique to each ethnic group, but these group differences underscore the importance of examining the within group variability of the pan-Latino population.

Interrelated Domains of Parenting: Socialization and Practices

As hypothesized, socialization messages served as predictors of parenting practices. These findings are consistent with Baumrind's seminal theory of parenting (Baumrind, 1975) in suggesting that values inform practices (i.e., authoritarian parents value unquestioning obedience and traditional structure and rely on punitive, forceful measures to control a child; authoritative parents value a child's individuality and autonomy and rely on the use of rationales and discussion to direct a child). Reconceptualizing values through a cultural lens, the present study found that MA and DA mothers who socialized their children to show respeto used more authoritarian practices; for example, to socialize her child that “it is not acceptable for children to talk back to adults,” a mother would choose a compatible parenting practice such as, “When my child asks why he has to conform, I state: because I said so, or I am your parent and I want you to.” Mothers who socialized their children to show independence, on the other hand, used more authoritative practices; for example, in socializing her son to “ask questions about what is happening around him,” a mother would choose a parenting practice compatible with that message such as “I help my child to understand the impact of behavior by encouraging him to talk about the consequences of his own actions.” In other words, MA and DA mothers appear to purposefully select parenting practices that best reinforce their socialization messages (Harwood et al., 1999). Importantly, however, socialization messages and parenting practices are not inevitably paired, because socialization may occur in situations that do not require behavior management, and behavior management may occur independently of socialization messages.

The Role of Acculturative Status

In examining acculturative status as a predictor of socialization messages, we expected acculturation to be related to more socialization of independence and less socialization of respeto, and enculturation to be related to more respeto and less independence (Gonzáles-Ramos et al., 1998). Our hypotheses were only partially confirmed. Findings suggest that acculturative status is an important predictor of socialization, but relations are complex, depend on the specific domain of acculturation/enculturation, and vary across ethnic groups. Consistent with the model, English language competence was negatively associated with respeto for both groups, and Spanish language competence was positively associated with respeto for DAs. However, MA ethnic cultural competence was positively associated with both respeto and independence. Among DA mothers, ethnic cultural competence was also positively associated with independence. In addition, DA ethnic identity and U.S. American identity were both positively related to respeto, and U.S. American identity and ethnic cultural competence were positively related to independence. Notably, with the exception of the language domain, all relations between acculturative status (i.e., acculturation and enculturation) and socialization (to U.S. and Latino cultures) were in the positive direction. It appears that greater psychological connection to either culture may be indiscriminately associated with more socialization, perhaps reflecting an underlying tendency for certain individuals to be more proactive in fulfilling their roles, whether as a parent or as a member of a specific cultural group. In a study of ethnically diverse university students, Schwartz, Zamboanga, Rodriguez, and Wang (2007) found that familial ethnic socialization was associated with aspects of both acculturation (i.e., American identity) and enculturation (i.e., ethnic identity), providing further evidence for a general association between these constructs.

Limitations and Future Directions

An important strength of the present study is the attention to ethnic subgroup differences within the pan-Latino culture (Fortuny, Hernandez, & Chaudry, 2010; Rosado & Elias, 1993). Findings support the validity of the model in both groups, but the specific paths that emerged as significant varied somewhat between MA and DA families. Differences were most pronounced in terms of acculturative status and may be related to the distinct sociodemographic profiles of the two groups. As reflected in the neighborhood characteristics of the sample, the DA community in NYC has a long-standing history, well-established ethnic enclaves and high rates of transnational migration (Duany, 1994), whereas the MA community is new and relatively geographically dispersed (Smith, 2005). The historical waves of immigration of a given group affect their socioeconomic status, ethnic group networks, available support, and human capital, all of which are posited to impact acculturative status and parenting (Yoshikawa, 2011). Considering these subgroup differences, it is not clear whether the present findings would generalize to other Latino subgroups, or to U.S.-born Latina mothers, given the study's focus on a construct such as acculturative status that is intricately tied to an individual and group's migration history and demographic profile. Future work is needed to examine the framework among families from different Latino ethnic groups and across generations. The exclusion of fathers is another clear limitation that warrants attention, particularly given that the vast majority of MA children (90%) and more than half of DA children (63%) from the present study came from two-parent households.

In addition, the framework should be tested with Latino families of young children who do not attend school. In the present study, the focus on children enrolled in school allowed for independent ratings of child functioning during a key developmental period as children transition to school and the roots of academic and behavior problems are established (Lahey, Loeber, Quay, Frick, & Grimm, 1992; Nagin & Tremblay, 1999). Given that many Latino children do not attend Pre-K or even K, however, caution is warranted in generalizing the present findings to Latino children who do not enter formal schooling until 1st grade.

It will also be important for future studies to examine Latino parenting at all levels of specificity (Dumka et al., 2009). Although the present study focused on an aggregate level of parenting practices that map onto broader dimensions of authoritarian and authoritative styles, the authoritarian scale for the DA sample had questionable internal consistency and warrants further study. Moreover, several researchers have argued for the need to consider Latino parenting at a microlevel (Calzada & Eyberg, 2002; Livas-Dlott et al., 2010) because results may be different when specific behaviors, such as the use of corporal punishment or the use of harsh criticism, are considered. A final limitation of the present study is the reliance on cross-sectional data, which precludes the examination of changes in acculturative status, parenting and child functioning. Longitudinal work is clearly needed to fully understand the early childhood development of Latino children.

Nonetheless, the present study makes an important contribution to the literature by providing empirical support for a framework of Latino parenting (Calzada et al., 2010) in which acculturative status and ethnic socialization of respeto and independence are key determinants in the use of the parenting practices mapping onto authoritative and authoritarian parenting styles. Although socialization messages are certainly just one of many predictors that explain Latino parenting practices, the present study underscores the importance of cultural values in the study of parenting and helps to explain why parenting may vary across cultures. Such variations have implications for children's functioning, and for the development of effective interventions to support Latino families. For example, clinicians who work with MA and DA mothers in parent training programs should examine not only the strategies mothers use to manage their children's behavior but also their motivation in selecting those strategies. To the extent that clinicians can help mothers explore how to instill important cultural values, without relying on parenting strategies that may inadvertently contribute to negative developmental outcomes, parent training programs will be more likely to help Latino families effect positive changes in child rearing and child functioning.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a K23 (K23 HD049730-01) and an R01 (R01 HD066122-02) to the first author. The first author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Robin Harwood, Catherine Tamis-LeMonda and Patrick Shrout, who served as mentors on the K award. The authors also wish to thank the collaborating school sites, the participant families, and the research staff who made this work possible.

References

- Baumrind D. Early socialization and adolescent competence. In: Dragastin SE, Elder G, editors. Adolescence in the life cycle: Psychological change and social context. Hemisphere; Washington, DC: 1975. pp. 117–143. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Effective parenting during the early adolescent transition. In: Cowan PA, Heatherington EM, editors. Family transitions. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1991. pp. 111–164. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Child rearing dimensions relevant to child maltreatment. In: Lerner R, editor. Child maltreatment and optimal care giving in social contexts. Garland; New York, NY: 1995. pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Canino GJ, Davies M, Zhang H, Ramirez R, Lahey BB. Prevalence and correlates of antisocial behaviors among three ethnic groups. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:465–478. doi: 10.1023/a:1012279707372. doi:10.1023/A:1012279707372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buriel R. Childrearing orientations in Mexican American families: Influences of generation & socio-cultural factors. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1993;55:987–1000. doi:10.2307/352778. [Google Scholar]

- Buriel R, Mercado R, Rodriguez J, Chavez JM. Mexican American disciplinary practices and attitudes toward child maltreatment: A comparison of foreign- and native-born mothers. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1991;13:78–94. doi:10.1177/07399863910131006. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Tena CO, Knight GP, Carlo G. The socialization of prosocial behavioral tendencies among Mexican American adolescents: The role of familism values. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17:98–106. doi: 10.1037/a0021825. doi:10.1037/a0021825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ. Unpublished measure. New York University School of Medicine; New York, NY: 2007. Cultural socialization of Latino children. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Eyberg SM. Self-reported parenting practices in Dominican and Puerto Rican mothers of young children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:354–363. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_07. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Fernandez Y, Cortes DE. Incorporating the cultural value of respeto into a framework of Latino parenting. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:77–86. doi: 10.1037/a0016071. doi:10.1037/a0016071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona PG, Nicholson BC, Fox RA. Parenting among Hispanic and Anglo-American mothers with young children. Journal of Social Psychology. 2000;140:357–365. doi: 10.1080/00224540009600476. doi:10.1080/00224540009600476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Latin-American, Caribbean and Latino Studies: Latino Data Project . The Latino population of New York City in 2007. Graduate Center City University of New York; New York, NY: 2008. Retrieved from http://web.gc.cuny.edu/lastudies/pages/dataproject.html. [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Pantin H, McBride C, Briones E, Kurtines W, Szapocznik J. Ecodevelopmental correlates of behavior problems in young Hispanic females. Applied Developmental Science. 2002;6:126–143. doi:10.1207/S1532480XADS0603_3. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Gaitan C. Socializing young children in Mexican-American families: An intergenerational perspective. In: Greenfield PM, Cocking RR, editors. Cross cultural roots of minority child development. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1994. pp. 55–86. [Google Scholar]

- Domenech Rodríguez M, Donovick MR, Crowley SL. Parenting styles in a cultural context: Observations of “protective parenting” in first-generation Latinos. Family Process. 2009;48:195–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01277.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duany J. Quisqueya on the Hudson: The transnational identity of Dominicans in Washington Heights. Dominican Research Monographs, The CUNY Dominican Studies Institute; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Gonzales NA, Bonds DD, Millsap RE. Academic success in Mexican origin adolescent boys and girls: The role of mothers' and fathers' parenting and cultural orientation. Sex Roles. 2009;60:588–599. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9518-z. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9518-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Roosa MW, Jackson KM. Risk, conflict, mothers' parenting, and children's adjustment in low-income, Mexican immigrant, and Mexican American families. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1997;59:309–323. doi:10.2307/353472. [Google Scholar]

- Florsheim P, Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D. Family processes and risk for externalizing behavior problems among African-American and Hispanic boys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:1222–1230. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1222. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.64.6.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortuny K, Hernandez DJ, Chaudry A. Young children of immigrants. The Urban Institute No. 3. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.urban.org/url.cfm?ID=412203.

- Foucault DC, Schneider BH. Parenting values and parenting stress among impoverished village and middle-class small city mothers in the Dominican Republic. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;33:440–450. doi:10.1177/0165025409340094. [Google Scholar]

- Fracasso MP, Busch-Rossnagel NA, Fisher CB. The relationship of maternal behavior and acculturation to the quality of attachment in Hispanic infants living in New York City. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1994;16:143–154. doi:10.1177/07399863940162004. [Google Scholar]

- Fridrich AH, Flannery DJ. The effects of ethnicity and acculturation on early adolescent delinquency. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1995;4:69–87. doi:10.1007/BF02233955. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller B, Garćia Coll C. Learning from Latinos: Contexts, Families, and Child Development in motion. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:559–565. doi: 10.1037/a0019412. doi:10.1037/a0019412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble WC, Ramakumar S, Diaz A. Maternal and paternal similarities and differences in parenting: An examination of Mexican-American parents of young children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2007;22:72–88. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.11.004. [Google Scholar]

- George D, Mallery P. SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. 11.0 update. 4th ed. Ally & Bacon; Boston, MA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Coxe S, Roosa MW, White RMB, Knight GP, Zeiders KH, Saenz D. Economic hardship, neighborhood context, and parenting: Prospective effects on Mexican American adolescents' mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;47:98–113. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9366-1. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9366-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Morgan-Lopez A, Saenz D, Sirolli A. Acculturation and the mental health of Latino youths: An integration and critique of the literature. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States. Greenwood; Westport, CT: 2002. pp. 45–74. [Google Scholar]

- González-Ramos G, Zayas LH, Cohen EV. Child-rearing values of low income, urban Puerto Rican mothers of preschool children. Professional Psychology: Practice and Research. 1998;29:377–382. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.29.4.377. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Henry DB, Florsheim P. Patterns of family functioning and adolescent outcomes among urban African American and Mexican American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:436–457. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.436. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.14.3.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau JM, Azmitia M, Quattlebaum J. Latino families: Parenting, relational, and developmental processes. In: Villarruel F, Carlo G, Grau J, Azmitia M, Cabrera NJ, Chahin TJ, editors. Handbook of U.S. Latino psychology. Developmental and community-based perspectives. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2009. pp. 153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield PM. Linking social change and developmental change: Shifting pathways of human development. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:401–418. doi: 10.1037/a0014726. doi:10.1037/a0014726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Dittus P, Jaccard J, Johansson M, Bouris A, Acosta N. Parenting practices among Dominican and Puerto Rican mothers. Social Work. 2007;52:17–30. doi: 10.1093/sw/52.1.17. doi:10.1093/sw/52.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CH, Nelson DA, Robinson C, McNeilly-Choque MK. Overt and relational aggression in Russian nursery-school-age children: Parenting style and marital linkages. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:687–697. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.4.687. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.34.4.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood RL. The influence of culturally derived values on Anglo and Puerto Rican mothers' perceptions of attachment behavior. Child Development. 1992;63:822–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01664.x. doi:10.2307/1131236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood RL, Schoelmerich A, Schulze PA, Gonzalez Z. Cultural differences in maternal beliefs and behaviors: A study of middle-class Angle and Puerto Rican mother-infant pairs in four everyday situations. Child Development. 1999;70:1005–1016. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00073. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Bush KR, Roosa MW. Parenting and family socialization strategies and children's mental health: Low-income Mexican-American and Euro-American mothers and children. Child Development. 2003;74:189–204. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00530. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents' ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Cota MK, Bernal ME. The socialization of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic preferences among Mexican American children: The mediating role of ethnic identity. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1993;15:291–300. doi:10.1177/07399863930153001. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Virdin LM, Roosa M. Socialization and family correlates of mental health outcomes among Hispanic and Anglo American children: Consideration of cross-ethnic scalar equivalence. Child Development. 1994;65:212–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00745.x. doi:10.2307/1131376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Loeber R, Quay HC, Frick PJ, Grimm J. Oppositional defiant and conduct disorders: Issues to be resolved for DSM-IV. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31:539–546. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199205000-00023. doi:10.1097/00004583-199205000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl KM, Malik N. Marital conflict, family processes, and boys' externalizing behavior in Hispanic American and European American families. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:12–24. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2801_2. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2801_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livas-Dlott A, Fuller B, Stein GL, Bridges M, Mangual Figueroa A, Mireles L. Commands, competence, and cariño: Maternal socialization practices in Mexican American families. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:566–578. doi: 10.1037/a0018016. doi:10.1037/a0018016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPhee D, Fritz J, Miller-Heyl J. Ethnic variations in personal social networks and parenting. Child Development. 1996;67:3278–3295. doi:10.2307/1131779. [Google Scholar]

- Manongdo JA, Ramirez Garcia JI. Maternal parenting and mental health of Mexican American youth: A bidirectional and prospective approach. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25:261–70. doi: 10.1037/a0023004. doi:10.1037/a0023004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardell-Czudnowski C, Goldenberg D. Developmental indicators for the assessment of learning. 3rd ed American Guidance Service; Circle Pines, MN: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Martınez EA. Child behavior in Mexican-American/Chicano families: Maternal teaching and child rearing practices. Family Relations. 1988;37:275–280. doi:10.2307/584562. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, Wells KC. Conduct disorders. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Treatment of childhood disorders. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1989. pp. 73–132. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Satorra A. Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. Sociological Methodology. 1995;25:267–316. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/271070 doi:10.2307/271070. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. 6th ed. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin D, Tremblay E. Trajectories of boys' physical aggression, opposition and hyperactivity on the path to physically violent and nonviolent juvenile delinquency. Child Development. 1999;70:1181–1196. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00086. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Coltrane S, Duffy S, Buriel R, Dennis J, Powers J, French S, Widaman K. Economic stress, parenting, and child adjustment in Mexican American and European American families. Child Development. 2004;75:1632–1656. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00807.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. Antisocial boys. Castalia; Eugene, OR: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Planos R, Zayas LH, Busch-Rossnagel NA. Acculturation and teaching behaviors of Dominican and Puerto Rican mothers. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17:225–236. doi:10.1177/07399863950172006. [Google Scholar]

- Planos R, Zayas LH, Busch-Rossnagel NA. Mental health factors and teaching behaviors among low income Hispanic mothers. Families in Society. 1997;78:4–12. doi:10.1606/1044-3894.732. [Google Scholar]

- Reese L. Parental strategies in contrasting cultural settings: Families in Mexico and “El Norte.”. Anthropology and Education Quarterly. 2002;33:30–59. doi:10.1525/aeq.2002.33.1.30. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. BASC-2: Behavioral assessment system for children manual. 2nd ed. American Guidance Service; Circle Pines, MN: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson C, Mandleco B, Olsen SF, Hart CH. Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: Development of a new measure. Psychological Reports. 1995;77:819–830. Retrieved from PsycINFO database. doi:10.2466/pr0.1995.77.3.819. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez BL, Olswang LB. Mexican-American and Anglo-American mothers' beliefs and values about child rearing, education, and language impairment. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2003;12:452–462. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2003/091). doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2003/091) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Morgan-Lopez A, Cree W, Specter M. Ethnic culture, poverty, and context: Sources of influence on Latino families and children. In: Contreras JM, Neal-Barnett A, Kerns K, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. Greenwood; Westport, CT: 2002. pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Rosado JW, Elias MJ. Ecological and psychocultural mediators in the delivery of services for urban, culturally diverse Hispanic clients. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1993;24:450–459. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.24.4.450. [Google Scholar]

- Samaniego RY, Gonzales NA. Multiple mediators of the effects of acculturation status on delinquency for Mexican American adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:189–210. doi: 10.1023/A:1022883601126. doi:10.1023/A:1022883601126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Rodriguez L, Wang SC. The structure of cultural identity in an ethnically diverse sample of emerging adults. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2007;29:159–173. doi:10.1080/01973530701332229. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RC. Mexican New York: Transnational lives of new immigrants. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, Rose R, Bacallao ML. Acculturation and Latino family processes: How cultural involvement, biculturalism, and acculturation gaps influence family dynamics. Family Relations. 2008;57:295–308. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00501.x. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Lamborn S, Darling N, Mounts N, Dornbusch S. Over-time changes in adjustment and competence among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Development. 1994;65:754–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00781.x. doi:10.2307/1131416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau The Hispanic population: 2010. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf.

- Varela RE, Vernberg EM, Sanchez-Sosa JJ, Riveros A, Mitchell M, Mashunkashey J. Parenting style of Mexican, Mexican American, and Caucasian Non-Hispanic Families: Social Context and Cultural Influences. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:651–657. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.651. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H. Immigrants raising citizens. Russell Sage Foundation; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zea MC, Asner-Self KK, Birman D, Buki LP. The Abbreviated Multidimensional Acculturation Scale: Empirical validation with two Latino/Latina samples. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2003;9:107–126. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.2.107. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.9.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman RS, Khoury EL, Vega WA, Gil AG, Warheit GJ. Teacher and parent perceptions of behavior problems among a sample of African American, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white students. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23:181–197. doi: 10.1007/BF02506935. doi:10.1007/BF02506935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]