Abstract

Palliative medicine must prioritize the routine assessment of the quality of clinical care we provide. This includes regular assessment, analysis, and reporting of data on quality. Assessment of quality informs opportunities for improvement and demonstrates to our peers and ourselves the value of our efforts. In fact, continuous messaging of the value of palliative care services is needed to sustain our discipline; this requires regularly evaluating the quality of our care. As the reimbursement mechanisms for health care in the United States shift from fee-for-service to fee-for-value models, palliative care will be expected to report robust data on quality of care. We must move beyond demonstrating to our constituents (including patients and referrers), “here is what we do,” and increase the focus on “this is how well we do it” and “let’s see how we can do it better.” It is incumbent on palliative care professionals to lead these efforts. This involves developing standardized methods to collect data without adding additional burden, comparing and sharing our experiences to promote discipline-wide quality assessment and improvement initiatives, and demonstrating our intentions for quality improvement on the clinical frontline.

Keywords: quality, palliative care

Introduction

The specialty of palliative care has undergone remarkable growth over the past decade.1 The reasons for this growth are many, most notably, the simultaneous uptake of palliative philosophy into mainstream medical care coupled with the demonstration of the value in improving patients and health systems outcomes.2,3 There has been a conscious, discipline-wide effort to develop and communicate a growing evidence base, ultimately conveying a compelling data-driven story that argues for the need for palliative care, characteristics of best practice, and demonstrated benefit.4

Just as there is the need to develop and disseminate research-informed evidence on best palliative care, there is the need to ensure that the care provided at the clinical frontline aligns with expectations of best practice. This alignment meets the expectations on the horizon, demanding dramatic shifts in the way care is delivered, evaluated, and reimbursed across all medical disciplines. Similarly to other fields, palliative care across all aspects of the serious illness trajectory must be prepared to meet an evolving imperative for quality assessment, reporting, and monitoring. This requires greater participation by all members of the palliative care community in demonstrating high-quality care that respects the art and science of our practice. Here we review several critical areas related to quality in palliative care in order to understand where we are, outline the roadmap for where we need to go, and explore some approaches for getting there.

Improving the Quality of Care Is Intrinsic to Palliative Care

Routine quality assessment as a method to improve patient-centered care is an intrinsic component of the spirit of palliative care. Ensuring that all palliative care patients receive excellent care has been a priority for the hospice and palliative care movement since its early years. When reflecting on the varying quality of care for seriously ill and dying British patients in the 1970s, Dame Cicely Saunders was quoted as saying to a colleague, “We can only send our patients to (a named institution) when they are becoming unconscious and we can reassure the families that they will not realize where they are going.”5 Even during the formative years of the palliative care movement, Dame Saunders identified differences across institutions in quality of care provided. Parallel to the establishment of a clinical service came the recognition that not all services would be equal; quality would have to be monitored. Dame Saunders first identified this issue in hospice care; naturally, this attention extends to all other palliative care service models as well.

Sadly, poor processes of end-of-life care also have touched those who have been influential in the field of quality improvement in health care. Avedis Donabedian, who most people identify as the father of the modern health care quality movement, lamented on his own personal experience with end-of-life care in an interview with Fitzhugh Mullan.6 Dying of advanced prostate cancer, Dr. Donabedian noted several instances of lack of care coordination, delays and inefficiencies in care delivery, and a certain detachment between his care providers and understanding his personal story. He also remarked about the seemingly poor understanding of suffering in those with serious illness, and the continued misperceptions regarding the role of opioids, double effect, and providing comfort without hastening death. His experience was representative of standard practice at the time and led many health care quality experts to conclude that quality of palliative care in the United States must continue to evolve.

The Evolving Landscape of Quality and Value Within Health Care Reform

The way health care is delivered, evaluated, and reimbursed is rapidly changing. In the face of shrinking reimbursement and financially unsustainable practices, new models for evaluating value of care and matching that value to reimbursement are being developed. These have a common theme: transitioning from reimbursement systems that are highly dependent upon fee-for-service and undefined accountability, to value-based purchasing and accountable care organizations (ACOs) that stress physician and medical group responsibility for quality of care and outcomes.

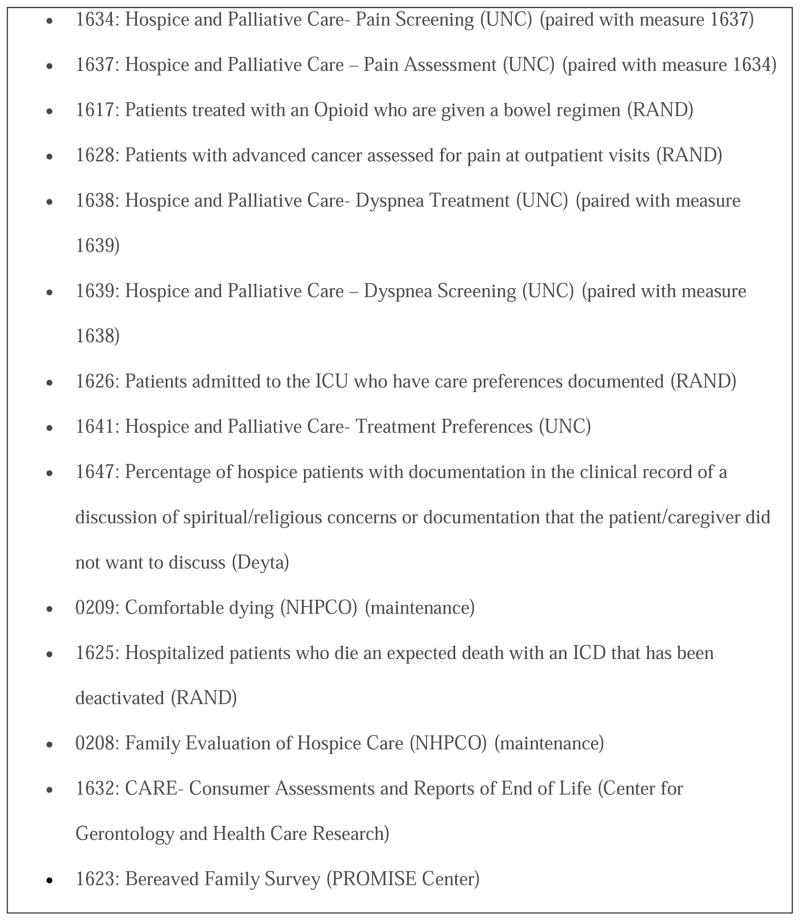

Emerging quality and performance metrics for palliative and supportive care herald evolving expectations for routine collection of quality monitoring data (e.g., the National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care,7 National Quality Forum,8 Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS] Conditions of Participation for hospice organizations, and CMS Physician Quality Reporting System [PQRS]). To date, the most widespread payer expectation is reflected by CMS’s PQRS, a quality measure-based, physician reimbursement program. The recent endorsement of quality measures for palliative care by the National Quality Forum (Fig. 1) was a key step in establishing PQRS for palliative medicine. At its inception, PQRS offered a bonus of up to 2% of physician Medicare fees for satisfactory reporting of data on quality. By 2015, the bonus will be replaced by a penalty system for incomplete reporting. Moreover, public reporting of the results of quality monitoring activities is increasing. For example, CMS plans to go live soon with its Physician Compare website, which is a publicly-reported dashboard for patients and payers to use to compare quality of care across physicians and practice organizations.

Fig. 1.

Endorsed National Quality Forum measures for palliative care.

Note: Numbers correspond to identification numbers assigned by the National Quality Forum.

Additionally, the program for Advanced Certification for Palliative Care by The Joint Commission (TJC) places continued emphasis on continuous quality assessment and improvement. As announced by TJC, a key eligibility criterion for Advanced Certification is the demonstration of using data capture on the provision of care quality to drive continuous performance improvement. Meeting these expectations requires mature, tested processes for quality monitoring and improvement efforts that address areas for optimization in timely and effective ways.

Most importantly, palliative care needs to foster active quality monitoring to ensure that definitions of quality are clinically derived and tested, rather than externally imposed. Major medical specialties already recognize the importance of quality in health care delivery. For example, since 2007, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has conducted a discipline-wide quality assessment program called the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI).9 Using retrospective chart review and abstraction, any outpatient oncology practice with at least one ASCO member can participate in uploading data that will inform semi-annual reports on conformance to a set of disease-specific, end-of-life care, and supportive/symptom management metrics. Aggregate analyses are reported back to QOPI participants to provide feedback and benchmarks to identify areas of excellence and improvement. Frequent data collection cycles have demonstrated value in improving adherence to quality measures;10 in some states, oncology organizations have leveraged “QOPI-Certification” for preferred relationships with payers and advocacy groups.11 In fact, ASCO has been a leader in quality measurement in supportive and palliative care, rapidly evolving the QOPI measures to include these domains.

There exists great potential for developing such infrastructure and programs in palliative care. Current efforts like the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) National Palliative Care Registry and the Palliative Care Quality Network represent excellent examples of how collaborative initiatives can inform a greater understanding of the structure and processes of palliative care delivery. Another ongoing initiative from the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAHPM) termed “Measuring What Matters” aims to define a set of high-value quality measures for our field. These highlight the significant possibilities in our field to stay in step with other clinical disciplines.

Reconciling With the “Art” of Palliative Care

Many may worry that any discussion involving quality in palliative care ultimately means transitioning to “cookbook medicine,” where conformance to a standard would be prioritized over patient-centered care. Some also may worry that in meeting the same pressures of health care reform faced by other disciplines, palliative care may lose its narrative in an effort to make care more normative. Reflecting on the historical approaches to quality assurance (QA) that many of us were taught, this is a reasonable worry. Previous techniques for QA stressed methods to find the defective person (i.e., “the bad apple”) and pressure him/her into conforming to care processes in line with all of his/her peers. This process looked for problematic clinicians and used financial, punitive, or coercive means to bring about behaviors consistent with the majority, largely ignoring important process factors for why the “right thing” was so hard to accomplish. Or conversely, why the “wrong thing” was so easy to do.

Recent approaches of continuous quality improvement (CQI) take a more iterative approach that aims to reduce and eventually eliminate “unexplained clinical variation.” Reducing such variation addresses the root of many of health care’s inefficiencies, excess costs, and poor outcomes. CQI calls for a cultural shift that relies on clinicians constantly asking themselves, “How could this process be better?” and “How can I impact this change?” The underpinnings of this approach view each clinician as an informed agent who can identify bad processes and implement changes. It views medical errors and inefficiencies as results, not of bad people, but of suboptimal processes of care. CQI also recognizes that heterogeneity in patient characteristics, values, and clinical settings dictates that prudent decision making formulated to reduce unnecessary clinical variation does not mean that 100% of care may meet a quality measure. A current example of this type of approach comes from the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign. This campaign, in which the AAHPM recently participated, aims to identify five areas of low value services that clinicians and patients should question – but not necessarily eliminate. Sometimes, clinician variance from standard processes meets a patient-centered wish or value. Certainly, palliative care practitioners understand the importance of honoring some requests to promote quality of life and ease suffering. This focus cannot change on the way to standardizing our best practices.

The newer CQI approach also recognizes the need for “balance measures.” These types of measures complement usual care process measures by serving as a “check and balance” to limit unintended or unwarranted consequences from over-adherence to other measures. For example, all palliative care clinicians have cared for a patient who underwent an unnecessary health maintenance examination (e.g., screening colonoscopy or Pap smear) in the setting of an unrelated, terminal disease. In this case, the usual metric that all patients over age 50 undergo colorectal cancer screening is balanced with a measure that acknowledges that such screening is not appropriate in a person with a limited life expectancy.

Further, there is increased recognition that the patient voice is an important component of the health care quality equation. Patient-centered decision making, patient preferences, and patient values are now increasingly appreciated when quality is measured and reported. Currently, these are measured through patient and family satisfaction with care surveys. In the future, a broader portfolio of approaches may assess the delivery of a patient-centered process (e.g., “Pain was treated in a manner acceptable to the patient”) rather than a clinician-directed process (e.g., “An opioid was given to all patients with moderate/severe pain”). Overall, when considering people over processes, clinical relevance over rote adherence, and patient values above filling checkboxes, many may find quality improvement in health care is transitioning to being much more practical and implementable than a decade ago.

Short-Term Priorities – “Getting to Good”

Four key areas will help further high-quality palliative care tailored to individual and caregiver needs. Approaches are still in evolution.

Further Define “High-Quality Palliative Care”

Current evidence development focuses on palliative care’s impact on quality of life, caregiver satisfaction, and possibly survival. Similarly, it is important to outline what structural (e.g., team make-up, team member expertise), process (e.g., how spiritual assessments are performed), and outcome (e.g., how is value to a hospital calculated?) characteristics yield the highest quality care. In other words: “What is in the palliative care syringe?” Clearly not new questions for the field, we are left refining many answers to some of the same questions from a decade ago:

Great strides have been made by the National Quality Forum and National Consensus Panel on Palliative Care; several consensus documents from CAPC12–15 also strengthen our knowledge in these areas. These are complemented by evidence from key studies about the components of outpatient palliative care that may improve patient-centered outcomes in advanced cancer.16–18 However, the majority of the information describing the characteristics of high-quality palliative care originates from hospital-based consultation services. We need to expand exploration of the characteristics of quality palliative care service delivery to encompass the diverse and heterogeneous settings in which patients require care. For example, quality measures pertinent to outpatient19 and community-based palliative care settings20 are needed to complement the hospital-based measures.

We also need to expand our thinking in terms of the relationship between palliative care quality and demonstration of value. Recent attention on value in health care has emphasized the need for reducing costs while increasing quality, and, in fact, palliative care has matured alongside a philosophy of cost avoidance and containment. However, this viewpoint has placed several challenges on our field that requires shaping the conversation differently. Becoming a service of “loss leaders” has limited the ability of palliative care programs to expand personnel and venture into new horizons that have unproven cost avoidance benefits. When those outside the field see the value of our services as mainly avoiding costs, we leave ourselves unprepared to demonstrate that palliative care improves overall care quality through also increasing patient-centered care. Demonstrating that we improve quality of care for entire populations, with cost avoidance being a natural downstream benefit – but not the only benefit – will further the growth of our services and acceptance of our care philosophy.

Strengthen Current Quality Monitoring Efforts

The discipline of palliative care must update its processes for quality assessment, monitoring, reporting, and improvement. This task requires building infrastructure to efficiently incorporate data that harnesses the experiences of individuals and organizations to lead to generalizable knowledge for the field. This requires careful planning to leverage the power of the collective while also respecting the autonomy and independence of each organization. In other words, this represents a paradigm shift to reflect the mantra of “collecting [data] locally, but affecting [understanding of the quality of care] globally.”

Currently, two uncoordinated retrospective approaches to quality monitoring are used in palliative care: singular, program-level efforts and retrospective analysis of registry and administrative claims data. Individual organization-level assessments are the most common approach, usually consisting of labor-intensive chart review to document program-level conformance to chosen metrics. Recent studies have questioned the validity and reliability of retrospective chart abstraction;21,22 serious errors in over- and under-estimation of quality conformance are demonstrated when abstracted clinical documentation data are repurposed for quality monitoring.23 Ideally, clinical documentation would contribute to clinical and quality data collection simultaneously. In fact, the lack of value in impacting individual, patient-level care becomes the foremost roadblock to clinician acceptance of regular data collection on quality.24 In palliative care, we need to aspire to a vision of real-time data collection and reporting that has immediate clinical value to providers.

The other approach, using administrative data, remains limited because of concerns of comprehensiveness and logistical ability. Large health system and payer claims databases often lack the level of clinical data (e.g., cancer stage, coronary vessel name and degree of obstruction in coronary artery disease, hemoglobin A1c percentage in diabetes) needed for detailed assessment of the adequacy of clinical care delivered or to inform specific quality metrics. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and other patient-reported data, which capture the patient voice such as symptoms and goals of care, are almost never recorded in administrative datasets; yet the patient report is critical for palliative care. And when patients cannot report their own distress (e.g., delirium, sedation), caregiver-reported data should be considered as an important adjunct to usual clinical data. Combining claims data, or with clinical chart abstractions, faces the same validity and reliability issues previously mentioned and is cumbersome, logistically difficult, and expensive. The addition of electronic health record (HER) data may improve the utility of these datasets for palliative care, but this remains to be seen. Although valuable to inform program-level questions or for short-term studies, retrospective quality assessment through claims data is inadequate for continuous quality monitoring.25

Achieving a system of (rapid) learning quality improvement (Fig. 2), which intelligently interprets aggregated clinical and administrative data into usable knowledge, requires evolving from the current approach that largely comprises individual, retrospective efforts to an approach that is prospective, coordinated, and collaborative. Working this way ensures processes are iterative and stay “rapid” as technology and algorithms are integrated with the model. This parallels similar rapid learning health care efforts in other areas.26

Fig. 2.

Rapid-learning quality improvement.

Empower Providers to Take Ownership of Palliative Care Quality Activities

As outlined by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), health care providers must be considered as vital partners in the data collection processes for quality monitoring, not merely customers of the knowledge gained.24 Partnership occurs at two levels of participation: during planning and analysis, and during routine clinical documentation. Ensuring data timeliness and validity requires that data on the quality of care be recorded simultaneously with clinical data, not post-hoc during retrospective chart review, or ad-hoc during temporary quality initiatives. This means that the data elements required to inform quality measures need to be clinically relevant, and directly embedded in clinical notes. Health information technology (HIT) systems can support the collection of critical data points simultaneously with episodes of care. Clinician goals for quality monitoring are supported through real-time feedback. Further, HIT-enabled approaches overcome the challenge of third-party peer review, which is disliked and mistrusted by physicians and a toxic method of change management.

Another way to grow clinician involvement is through building palliative care clinician familiarity with terminology, techniques, and processes in quality improvement (Table 1). Meeting this need prepares clinicians to effectively communicate with leadership within and outside their organizations on the quality, outcomes, and value of their palliative care programs. This aids in programmatic growth and sustainability and ensures that the palliative care team remains a priority within hospitals and health systems

Table 1.

Key Terms for Understanding Quality in Palliative Care

| Term | Definition | Implications for Palliative Care |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Health Care | The degree to which health care services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge. | The emphasis on consistency with current knowledge highlights evidence-based practice as a hallmark of quality care, not only conformance with developed quality measures. |

| Value | “Value of Care” as a measure of specified stakeholder’s (such as an individual patient’s, consumer organization’s, payer’s, provider’s, government’s, or society’s) preference-weighted assessment of a particular combination of quality and cost of care performance. | Largely, palliative care has defined its value to a health care system through its cost savings and avoidance; its quality of care must now be stressed. |

| Performance Measurement | The mechanism for measuring value. The Institute of Medicine recently called for “a coherent, robust, integrated performance measurement system that is purposeful, comprehensive, efficient, and transparent. | This underscores the needs for systems, that have farther scope than individual projects. |

| Pay for Performance | Enhancing or reducing payments through fee schedules, bonuses or other incentives based on performance on certain measures of quality and value. | This is the result of an evolution past fee-for- service models where quantity of care is less valued than quality or outcomes of care. |

| Transparency | Refers to providing information about quality or value to policymakers, providers and consumers of health care services. Patients and their families have the right to the information that will help them make informed choices about health care services. If relative value information is made available to health care purchasers, the expectation is that they will make more informed decisions and perhaps reward higher value providers with their business. | With a national trend towards publicly-available reporting, this piece is key for palliative care to remain in step with other medical disciplines. |

Understand Current Knowledge Gaps in Palliative Care Quality

It is tempting to assert that palliative care is quality care. A growing body of research evidence supports the benefits, or “effectiveness” of specialty palliative care. Also, studies demonstrate the cost savings and health care utilization avoidance benefits of palliative care. However, the Institute of Medicine’s definition of quality health care includes four additional domains – safety, timeliness, equity, and patient-centeredness – that are not well represented in current research.

Data about the safety, timeliness, and equity of the care we provide are critical gaps in our evidence base. We presume that palliative care is safe, yet the evidence is immature. Several interventions we routinely use (e.g., ketamine as an adjuvant for pain management,27 discontinuation of cardiac medications in hospice28) may have marginal benefits or unintended harmful consequences. Enrollment in hospice and access to consultative palliative care in hospitals are frequently delayed,29 highlighting an important gap in the timeliness of our services. Palliative care has yet to demonstrate non-disparate, equal care across races and populations. Palliative care access varies by states and regions and minorities are utilizing these services at lower rates than other populations.30–32 Palliative care cannot be considered of the highest quality until these issues are prioritized and addressed. And, as research evidence evolves, our quality measures need to evolve accordingly in order to ensure implementation of evidence into clinical practice.

The Long-Term Roadmap Moving Forward – “Going from Good to Great”

There remain several steps between the current environment — where quality demonstration is sporadic and seen as an adjunct to care delivery — to one where quality monitoring is continuously integrated within clinical care delivery and documentation. Further, quality monitoring must be coordinated and networked between multiple providers and organizations. The roadmap to achieve these lofty goals includes at least six, fundamental steps:

1. All palliative care team members (physicians, advance practice providers, nurses, social workers, chaplains) should lead the effort to make quality assessment and reporting a discipline-wide expectation

Impending changes to how health care is delivered and evaluated requires us to regard quality-related activities as crucial to the viability and growth of our organizations and discipline. Providers must lead this effort by being informed and engaged participants in the process to conduct quality assessments, address areas for improvement, and report successes to colleagues, administrators, and payers. Quality-related activities must be efficient and useful, not burdensome. Quality champions must be encouraged to report processes that are easily implemented. Further, we must provide an adequate stage equal to that of educational and research reports in order to share lessons learned and future directions.

2. Develop, standardize, and share highly effective methodologies for quality activities

Quality-related activities must be efficient, impact daily patient care, and integrate into usual clinical activities. Historical approaches, such as retrospective chart abstractions and registry reviews to evaluate quality are outdated. Prospective data collection, such as in EHRs and electronic and billing databases, should be the norm. Without such a transition, the needs of “my patient” will never be met at the point that important clinical decisions need to be made if information on quality is only available from a de-identified, aggregated, six-month, retrospective cohort. These data work well to audit practices, but perform poorly in guiding the care of individual patients.

3. Foster existing, and develop new, collaborations for quality data collection, sharing, and analysis

Historically, palliative care has been handicapped by the problem of the “siloed Excel file” (Microsoft Office™). Almost every palliative care organization and consultation team has a local database to warehouse operations and service data. These files are generally not standardized in terms of data elements, are not interoperable in terms of answer choices, nor transferable between organizations because of the lack of formal agreements for data sharing. Pooling and sharing data are necessary to multiply the effectiveness of lessons learned. This requires careful development of interoperable and scalable data systems to compare experiences across practices. In doing so, champions, and areas for improvement where organizations can assist each other, can be identified.

4. Develop and rigorously test quality measures for palliative care

The National Quality Forum has recently endorsed the first set of palliative care quality measures (Fig. 1). This is an important step to incorporate quality measures into private and public payer-based reimbursement programs. To keep in step with the increased use of quality measures across all aspects of health care, we must look towards the future by developing, testing, and implementing the next generation of measures. These new measures must be rigorously tested for feasibility in busy clinical environments and validated for content, reliability, and ability to inform quality assessment and improvement efforts. Then, we can ensure that specific measures are valuable, useful, and doable in all settings where palliative care is delivered.

5. Outline a collective agenda for quality-based research

Through its evolving research infrastructure, palliative care sits uniquely poised to be the driver of linking high-quality care with improvement in patient, caregiver, and health system outcomes. Several questions regarding effective palliative care team structures, value of processes outside of symptom management and psychosocial care (e.g., spiritual assessments), and outcomes beyond cost containment and quality of life (e.g., depression, survival) remain unanswered.

Building the evidence base through research should incorporate both usual and learning health care methods. Learning health care approaches leverage the massive amounts of clinical, administrative, and billing data produced through usual clinical encounters to gain new knowledge. This does not require development of new data collection tools or registries; rather, it uses the wealth of information found within current databases to study questions related to comparative effectiveness and outcomes. This promotes an iterative approach, where small, continuous evolutions in the evidence base result from regular analyses of existing data sources. Thus, we acknowledge that the best practices are not yet completely understood, but will be adjusted along the way as new wisdom is gained.

6. Lead from the front and drive the conversation of quality benchmarking, metrics, and accountability across all of medicine

Medical disciplines have remained reactive to expectations placed by payers and accreditors to define quality palliative care. Positioning instead in a proactive stance will aid the uptake of quality efforts within our field. Ultimately, palliative care professionals should define the quality of care our patients receive, and demonstrate what it looks like. We should be stewards for best quality care across medicine. We should collectively push the boundaries from “novel” to “standard,” and from “sometimes” to “always.” There is an important imperative to accomplish two tasks simultaneously: get it “right” and make it “routine.” Routinely performing an ineffective process does not advance our field any more than occasionally performing an effective process. All patients, in all settings, at all times, should expect to receive similar, highly effective palliative care that is vetted, tested, benchmarked, and re-examined continuously.

Our Collective Imperative

Palliative care is uniquely positioned, as it continues to refine both its mission and expand its access, to serve as the model for other disciplines in the arena of quality. We have not grown too large to change. We remain flexible and agile to influence dramatic improvements in care delivery. This occurs through simultaneously fostering quality monitoring programs on individual program levels while developing community and academic partnerships to compare, share, and benchmark data. Because we span multiple chronic diseases, include team members from various disciplines, and deliver care in diverse locations, developing a central quality-related agenda presents a unique challenge. The challenge also includes respecting the heterogeneity of our field while also answering the demands placed outside of ourselves to report on quality. Just as health care systems are embracing the multidisciplinary and comprehensive care plan approach innate to clinical palliative care, we should be prepared to use the same intensity and cooperative nature to transition the conversation. This transition shifts the messaging within ourselves and to our peers from “This is what we do” to “This is how we do it well.”

Acknowledgments

Dr. Abernethy has research funding from the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Cancer Institute, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, DARA, Glaxo Smith Kline, Celgene, Helsinn, Dendreon and Pfizer; these funds are all distributed to Duke University Medical Center to support research including salary support for Dr. Abernethy. Pending industry funded projects include: Genentech, Bristol Myers Squibb, Insys, and Kanglaite. In the last two years she has had nominal consulting agreements with or received honoraria from (<$10,000 annually) Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer. Further consulting with Bristol Meyers Squibb is pending in 2013, for role as Co-Chair of a Scientific Advisory Committee. Dr. Abernethy has a paid leadership role with American Academy of Hospice & Palliative Medicine (President). She has corporate leadership responsibility in AthenaHealth (health IT company), Advoset (an education company that has a contract with Novartis), and Orange Leaf Associates LLC (an IT development company).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None of the other authors have any disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Morrison RS, Maroney-Galin C, Kralovec PD, Meier DE. The growth of palliative care programs in United States hospitals. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:1127–1134. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meier DE. Increased access to palliative care and hospice services: opportunities to improve value in health care. Milbank Q. 2011;89:343–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00632.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor DH., Jr Palliative care and the search for value in health reform. N C Med J. 2011;72:229–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamal AH, Currow DC, Ritchie C, et al. The value of data collection within a palliative care program. Curr Oncol Rep. 2011;13:308–315. doi: 10.1007/s11912-011-0178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter R. Cicely Saunders - Founder of the hospice movement: Selected letters 1959–1999. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:149–151. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mullan F. A founder of quality assessment encounters a troubled system first and. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:137–141. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for quality palliative care: executive summary. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:611–627. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2004.7.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Quality Forum. A national framework for preferred practices for palliative and hospice care quality. Washington DC: National Quality Forum; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuss MN, Desch CE, McNiff KK, et al. A process for measuring the quality of cancer care: the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6233–6239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blayney DW, Severson J, Martin CJ, et al. Michigan oncology practices showed varying adherence rates to practice guidelines, but quality interventions improved care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:718–728. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blayney DW, Stella PJ, Ruane T, et al. Partnering with payers for success: quality oncology practice initiative, blue cross blue shield of michigan, and the michigan oncology quality consortium. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5:281–284. doi: 10.1200/JOP.091043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: a consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:17–23. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weissman DE, Morrison RS, Meier DE. Center to Advance Palliative Care palliative care clinical care and customer satisfaction metrics consensus recommendations. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:179–184. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Center to Advance Palliative Care inpatient unit operational metrics: consensus recommendations. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:21–25. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weissman DE, Meier DE, Spragens LH. Center to Advance Palliative Care palliative care consultation service metrics: consensus recommendations. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:1294–1298. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721–1730. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meier DE, Beresford L. Outpatient clinics are a new frontier for palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:823–828. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.9886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamal AH, Currow DC, Ritchie CS, Bull J, Abernethy AP. Community-based palliative care: the natural evolution for palliative care delivery in the u.s. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46:254–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dresselhaus TR, Luck J, Peabody JW. The ethical problem of false positives: a prospective evaluation of physician reporting in the medical record. J Med Ethics. 2002;28:291–294. doi: 10.1136/jme.28.5.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luck J, Peabody JW, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M, Glassman P. How well does chart abstraction measure quality? A prospective comparison of standardized patients with the medical record. Am J Med. 2000;108:642–649. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merry MD, Crago MG. The past, present and future of health care quality. urgent need for innovative, external review processes to protect patients. Physician Exec. 2001;27:30–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reinertsen JL, Gosfield AG, Rupp W, Whittington JW. IHI Innovation Series white paper. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2007. Engaging physicians in a shared quality agenda. Available from www.IHI.org. [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Brookings Institution. How registries can help performance measurement improve care: a white paper. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution; 2010. Available from http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2010/rwjf61984. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abernethy AP, Etheredge LM, Ganz PA, et al. Rapid-learning system for cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4268–4274. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.5478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hardy J, Quinn S, Fazekas B, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and toxicity of subcutaneous ketamine in the management of cancer pain. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3611–3617. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LeBlanc TW, Kutner JS, Ritchie CS, Abernethy AP. Discontinuation of statins in routine care settings. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:74–75. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-1-201307020-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin EW. Barriers to hospice: access delayed, access denied. Med Health R I. 2005;88:117–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Johnson KS, Curtis LH, Setoguchi S. Racial differences in hospice use and patterns of care after enrollment in hospice among Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2012;163:987–993. e983. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Tanis D, Tulsky JA. Racial differences in the growth of noncancer diagnoses among hospice enrollees. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:286–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Tanis D, Tulsky JA. Racial differences in hospice revocation to pursue aggressive care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:218–224. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]