Abstract

Gene targeting – homologous recombination between transfected DNA and a chromosomal locus – is greatly stimulated by a DNA break in the target locus. Recently, the RNA-guided Cas9 endonuclease, involved in bacterial adaptive immunity, has been modified to function in mammalian cells. Unlike other site-specific endonucleases whose specificity resides within a protein, the specificity of Cas9-mediated DNA cleavage is determined by a guide RNA (gRNA) containing an ~20 nucleotide locus-specific RNA sequence, representing a major advance for versatile site-specific cleavage of the genome without protein engineering. This article provides a detailed method using the Cas9 system to target expressed genes in mouse embryonic stem cells. In this method, a promoterless marker flanked by short homology arms to the target locus is transfected into cells together with Cas9 and gRNA expression vectors. Importantly, biallelic gene knockout is obtained at high frequency by only one round of targeting using a single marker.

Keywords: gene targeting, double-strand break (DSB), Cas9, embryonic stem cells, genome editing, homologous recombination

1. Introduction

Gene knockouts in mammalian cells have traditionally relied on homologous recombination between transfected DNA and the chromosomal locus, termed gene targeting [1]. This approach is generally inefficient, requiring the screening of large numbers of cell clones to identify those with the desired homologous integration event. Targeting expressed genes, however, provides an advantage in that homologous integration can be designed to lead to the expression of a promoterless selectable marker [2]. With this “promoter trap” approach, the frequency of targeting per se is not increased, but a large fraction of clones that express the marker will have undergone gene targeting; remaining clones will presumably have integrated the marker by chance near an active promoter. First developed in primate cells, promoter trap approaches were also applied to mouse cells [3], including embryonic stem (ES) cells [4]. Further enhancing the specific recovery of gene targeted clones, other elements in addition to those promoting transcription have been co-opted by a marker upon homologous integration, such as a translation start site and signal sequence for cell surface expression [5].

Homologous recombination is a DNA repair mechanism for lesions such as double-strand breaks (DSBs), whereby the damaged locus becomes converted to sequences from the unbroken homologous template – the donor, as first described in budding yeast [6, 7]. Traditional gene targeting is inefficient in part because the chromosomal locus to be modified is not subjected to prior DNA damage. It seems likely that the rare gene targeting events that do occur (10−5 to 10−6 per transfected cell) are initiated when there is chance DNA damage at the target locus. To determine whether the efficiency of gene targeting could be increased by DNA damage in the target locus, a DSB was introduced at a target locus by expressing the rare-cutting I-SceI endonuclease in mammalian cells that harbored an integrated I-SceI site [8, 9]. The DSB increased gene targeting several orders of magnitude [9, 10], including in mouse ES cells [11], such that the absolute frequency of targeting was as high as 0.1-1% of transfected cells [12-14]. In addition to gene targeting, mutagenesis occurred at the DSB site in a substantial fraction of clones [9], consistent with efficient and error-prone repair of the DSB via non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) [15]. Thus, both DSB repair pathways – homologous recombination and NHEJ – can be used for efficient genome modification, either for targeted modification or mutagenesis, respectively.

These model experiments using I-SceI-induced DSBs provide the paradigm for achieving efficient gene targeting and mutagenesis of loci [16], collectively termed “gene editing”. The first site-specific cleavage reagents that were designed for use throughout the genome involved the engineering of zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs), leading to the finding that induction of a DSB at a locus could result in biallelic gene targeting [17]. More recently, transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), which also require protein engineering to bind a specific DNA sequence, provided a more tractable alternative to ZFNs [18]. Simplifying the design even further, the recently adapted Cas9 system allows efficient establishment of RNA-guided DNA endonucleases [19, 20]. In this system, Cas9, a protein involved in the Streptococcus pyogenes adaptive immune response, binds a guide RNA (gRNA) which includes ~20 nucleotides complimentary to the target genomic locus; the only requirement is that the locus contains a NGG sequence (the PAM motif) downstream of the target sequence. The flexibility and convenience of the Cas9 system make it an ideal tool with which to induce a site-specific DSB for the promotion of gene targeting. Here, we describe a Cas9-mediated gene-targeting method for mouse ES cells that can efficiently generate biallelic gene targeting of expressed genes in one round of genome editing.

2. Methods

2.1 Overall strategy

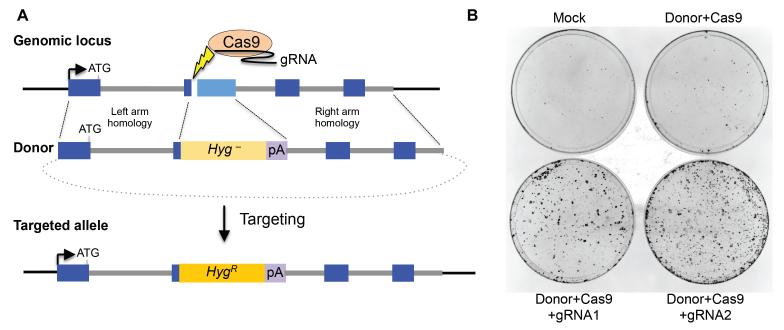

The gene targeting strategy involves a DSB introduced by Cas9 directed by a gRNA to the gene of interest (GOI) and a donor consisting of a promoterless selectable marker flanked by homology to the GOI (Figure 1A). Correct targeting of the GOI leads to expression of the marker and knockout of the targeted allele(s). As an alternative to gene targeting, error-prone NHEJ repair of the Cas9-mediated DSB can lead to gene mutagenesis by introducing frameshift mutations.

Figure 1.

Targeting an expressed gene with a Cas9/gRNA-mediated DSB to activate a promoterless marker in ES cells.

(A) Targeting scheme. The DSB (lightning bolt) is induced in the chromosome by Cas9/gRNA at the gene of interest (GOI). The donor fragment in the targeting vector contains homology to the GOI flanking a promoterless hygromycin resistance gene (Hyg−), which is cloned in frame into the exon, and a polyadenylation (pA) sequence. Gene targeting at the homology arms leads to HygR by capturing expression elements from the GOI. The targeting vector is introduced as a circular plasmid (dotted line). The example of the GOI in this chapter encodes the DNA damage response protein 53BP1, for which the first four exons (blue bars) of 28 total exons are shown. light blue bar, exon 2 segment not present in the targeting vector; arrow, transcription start site.

(B) Representative plates showing highly enhanced frequency of hygromycin resistant colony formation in mouse ES cells by gene targeting involving a Cas9/gRNA-mediated DSB (compare bottom two plates with inclusion of a gRNA expression vector in the transfection with either top plate with no gRNA vector or mock transfected). The gRNA sequence presented in the text is gRNA1.

2.2 Gene targeting scheme

The sequence targeted by the Cas9/gRNA for DSB formation (lightening bolt, Figure 1A) is contained within the segment between the two homology arms, such that it is not present in either the targeting vector or the correctly targeted allele to avoid unwanted Cas9/gRNA-mediated cleavage. Homology arms flanking the promoterless marker are 700-800 bp, although shorter arms are also likely to be efficient [21]. The marker, a hygromycin resistance gene (Hyg), is cloned as an in-frame fusion to the GOI, such that DSB-induced targeting leads to its expression from the endogenous promoter and translation starting from the ATG of the GOI, with only a very short N-terminal peptide expressed from the GOI fused to Hyg. Correct targeting also deletes most of the targeted exon. Several variations of this scheme are possible. For example, we have also obtained larger deletions involving multiple exons by using a right homology arm several kb downstream from the DSB site.

In the method described here, the GOI encodes the DSB repair protein 53BP1 [22]. In principle the approach can be used to target any expressed gene, with the caution that biallelic disruption of essential genes would require adaptation of a conditional knockout strategy (see below).

2.3 Molecular cloning

2.3.1 Cas9 expression plasmid for mouse ES cells

A human codon-optimized Cas9 expression plasmid was obtained from Addgene (Plasmid 41815) [23]. For optimal expression in mouse ES cells, we used a pCAGGS vector, which expresses proteins from a strong synthetic promoter containing the CMV early enhancer and the chicken beta-actin promoter and in addition has a splice acceptor of the rabbit beta-globin gene [24, 25]. The published pCAGGS vector was modified to contain a multiple cloning site (XhoI, NotI, NheI, MfeI, SacI, KpnI, AgeI sites). The coding sequence of Cas9 was PCR amplified from Plasmid 41815 to include NheI sites at its ends and cloned by inserting the NheI-digested PCR fragment into the NheI site of the modified pCAGGS vector, generating pCAGGS-Cas9.

2.3.2 gRNA expression plasmids (estimated time: ~1 week)

An empty gRNA expression vector was obtained from Addgene (Plasmid 41824) [23]. Inserting a 19-bp sequence specific to the target locus into the empty vector creates a plasmid expressing the gRNA.

The choice of the specific sequence in the gRNA depends on several criteria. In this study, we chose to position the knockout mutation within a specific exon, exon 2, such that the peptide expressed from the GOI fused to Hyg was quite short (6 amino acids) yet the left homology arm could be sufficiently long without including the promoter (Appendix, point 1). Within this exon, the location of NGG PAM sequences, required for Cas9 cleavage [26], was determined and 19 bp sequences immediately 5′ to NGGs were considered as possible targets for cleavage. The final choice was based on proximity to the homology arms on the donor. Presumably, close proximity of the DSB to the homology arms increases the probability of gene targeting, since it results in less heterologous sequence at the DSB end(s) that can impair invasion into the donor sequence.

In principle, a 19 bp sequence is sufficiently long to be unique in the mammalian genome. However, some studies have raised concern that off-target sites can be cleaved, as only ~11 nucleotides in the gRNA upstream of the PAM sequence appear to be critical for Cas9 specificity [27, 28]. This aspect of Cas9 apparently requires more investigation, as recent reports suggest that off-target cleavage by Cas9 is insignificant [29]. If flexibility in the location of DSB induction (targeting) within a gene is possible, computational methods can be used to identify a unique target sequence. Otherwise, complementation of the knockout mutation may be important to verify that phenotypes are not due to off-target mutations. Efficiency of Cas9/gRNA cleavage can be checked by assays measuring mutagenesis of the target site (i.e., those using Surveyor or T7 endonuclease assays [30, 31]); however, a higher recovery of cells (colonies) that activate the promoterless hygromycin marker with gRNA expression is strong indication that the gRNA is effective (see below).

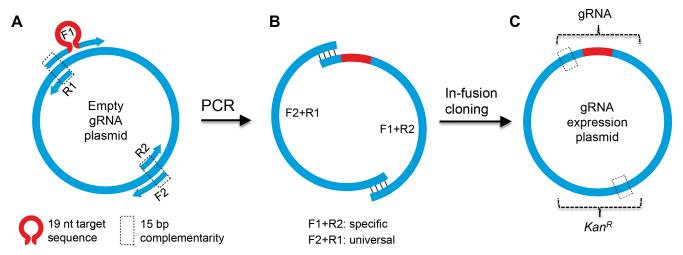

To construct gRNA expression plasmids, we developed an efficient protocol with a combination of PCR and “in-fusion” cloning (Clontech), making use of the complementarity of primer sequences, such that a circular plasmid is created from two amplified fragments (Figure 2). In brief, two separate PCR reactions are performed using the empty gRNA vector as the initial template. In one PCR reaction, the F1 forward primer contains the 19-nucleotide gRNA sequence and overlaps the U6 promoter; the R2 reverse primer is a universal primer that binds to the middle of the vector at the kanamycin resistance gene, KanR (Figure 2A). The second PCR reaction uses two universal primers: forward primer F2, which has 15 nucleotides at the 5′ end that are complementary to the 5′ end of R2, and reverse primer R1, which has 15 nucleotides at the 5′ end that are complementary to the 5′ end of F1. (Note: The amplicon from the F2+R1 PCR reaction can be used to generate multiple gRNA expression vectors, such that only one specific primer and one PCR reaction are necessary to construct each gRNA vector.) Products of both PCR reactions are gel purified and combined in the in-fusion reaction (Figure 2B). The resultant plasmid DNA is transformed into competent bacteria, selecting for kanamycin resistance (Figure 2C). The gRNA sequence in the final plasmid is sequenced to confirm that no errors were introduced during PCR.

Figure 2.

gRNA expression plasmid construction using an in-fusion approach.

(A) Two sets of PCR primers are used that bind to the empty gRNA plasmid: 1) a specific primer F1 that contains the 19 nucleotide (nt) target-specific sequence (red omega) and a universal primer R2 and 2) universal primers F2 and R1. Primers F1 and R1 have 15 nt complementarity at their 5′ end (dashed box); F2 and R2 similarly have 15 nt complementarity.

(B) The two PCR reactions result in two amplicons which share 15 bp of identity at each end (bars).

(C) The two amplicons are combined in an in-fusion reaction which has exonuclease activity to expose the complementarity. E. coli transformation with kanamycin (Kan) selection selects the gRNA expression plasmid. Note that while one primer set overlaps at the U6 promoter of the gRNA gene, the other overlaps at the KanR gene.

In-fusion PCR

Universal primers:

R1: 5′-CGGTGTTTCGTCCTTTCCAC

R2: 5′-ATCGCCTTCTTGACGAGTTC

F2: 5′-CGTCAAGAAGGCGATAGAAG

Specific primer:

F1 for 53BP1: 5′-AAGGACGAAACACCGGACCCTACTGGAAGTCAATGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGCAAG (Note that the underlined 19 nt is specific for this study at the 53BP1 locus and the bold G immediately upstream is the required initiation site for the U6 promoter.)

PCR reactions:

All PCR reactions were done with iProof High Fidelity DNA polymerase (BioRad Catalog No 172-5301).

Reaction #1: primers F1+R2, ~2 kb product

Reaction #2: primers F2+R1, ~2 kb product

PCR program:

98 °C, 1 minute

98 °C, 30 seconds

56 °C, 30 seconds

72 °C, 1 minute

Repeat steps 2-4 30 times

72 °C, 5 minutes

12 °C, holding temperature

In-fusion reaction:

Combine 1:1 volumes from the two PCR reactions with 1 μl of 5X in-fusion mix (Clontech Catalog No 101613) in a total volume of 5 μl. The reaction is incubated at 50 °C for 15 min, followed by bacterial transformation.

Sequencing primer:

U6seq: 5′-GACTATCATATGCTTACCGT

2.3.3 Donor plasmid (estimated time: ~2 weeks)

The donor plasmid was constructed by assembling three fragments – the left homology arm, the promoterless marker gene (Hyg−) with a bovine growth hormone (BGH) polyadenylation (pA) signal, and the right homology arm – into a pBluescript SKII+ vector (Figure 1A). The fragments were generated by high fidelity PCR with primers creating the proper flanking restriction sites, and cloned into an empty pBluescript vector by a two-step restriction digestion/ligation scheme. First, the left arm fragment digested with ApaI and BglII, the promoterless hygromycin gene digested with BglII and XhoI, and pBluescript digested with ApaI and XhoI were ligated (3-way ligation). Separately, the BGH pA fragment digested with XhoI and BglII, the right arm fragment digested with BglII and NotI, and pBluescript digested with XhoI and NotI were ligated. After sequencing of the two halves of donor on the two intermediate plasmids, the final donor plasmid was assembled in a second step simply by restriction digest cloning of one half of the donor into the plasmid containing the other half of the donor. The final sequence of the donor is contained in the Appendix (point 2).

Primers (creating desired flanking restriction sites, underlined, for cloning)

53BP1-LA ApaI-F: 5′-AAAGGGCCCTGACGGGAAAAGGGGGAGC 53BP1-LA BglII-R: 5′-AAAAGATCTCATCTGCTCCCCTGGAATGG 53BP1-RA BglII-F: 5′-AAAAGATCTAAAAAGCCTGAACTCACCGCG 53BP1-RA NotI-R: 5′-AAAGCGGCCGCTTGAAGTTGTAGGAGTTGAACG Hygromycin BglII-F: 5′-AAAAGATCTAAAAAGCCTGAACTCACCGCG Hygromycin XhoI-R: 5′-AAACTCGAGCTATTCCTTTGCCCTCGGAC BGHpA XhoI-F: 5′-AAACTCGAGGCCTCGACTGTGCCTTCTAG BGHpA BglII-R: 5′-AAAAGATCTTAGAGCCCACCGCATCCCC

PCR reactions

All PCR reactions were done with iProof High Fidelity DNA polymerase.

Reaction #1: primers 53BP1-LA ApaI-F + BglII-R, 0.7-kb product, mouse genomic DNA template

Reaction #2: primers 53BP1-RA BglII-F + NotI-R, 0.8-kb product, mouse genomic DNA template

Reaction #3: primers Hygromycin BglII-F + XhoI-R, 1-kb product, pgkhyg plasmid template

Reaction #4: primers BGHpA XhoI-F + BglII-R, 0.25-kb product, plasmid template (Addgene 22212) PCR program:

98 °C, 1 minute

98 °C, 30 seconds

60 °C, 30 seconds

72 °C, 30 seconds

Repeat steps 2-4 30 times

72 °C, 1 minutes

12 °C, holding temperature

2.4 ES cell transfection

Mouse ES cells were cultured using a standard protocol [32]. For gene targeting, cells were transfected by nucleofection with three plasmids – the donor plasmid and the Cas9 and gRNA expression vectors. Important control transfections leave out the gRNA plasmid, to verify that the absence of a DSB substantially reduces the recovery of HygR colonies, or the donor plasmid (or all plasmids, as a mock) to verify that the drug concentration is sufficient to kill all cells in the absence of a Hyg gene. Plasmids were prepared using Invitrogen Purelink Maxiprep (Catalog No K210017), which produces plasmids with low endotoxin (not endotoxin free).

Homemade (HM) buffer recipe

Solution I: 2 g ATP-disodium salt+1.2 g MgCl2[6*H2O] dissolved in 10 ml H2O

Solution II: 6 g KH2PO4+0.6 g NaHCO3+0.2 g glucose dissolved in 300 ml H2O, adjust PH to 7.4 with NaOH, add H2O to a final volume of 500 ml

Make 80 μl aliquots of solution I and 4 ml aliquots of solution II, store at −20 °C

Mix 80 μl of solution I and 4 ml of solution II for nucleofection, store at 4 °C (for up to 1 month). In our experience, nucleofection with HM buffer yields a similar transfection efficiency and cell mortality as electroporation of mouse ES cells.

Plasmid cocktails

For targeting: pCAGGS-Cas9 (1 μg)+gRNA plasmid (1 μg)+donor plasmid (2 μg)

For controls: no DNA (mock), pCAGGS-Cas9 (1 μg)+donor plasmid (2 μg)

(Note that controls could additionally contain a neutral plasmid (4 μg or 1 μg, respectively) to maintain equal DNA concentration; the neutral plasmid could, for example, be a GFP vector to determine transfection efficiency.)

Nucleofection

20-24 hours before transfection, split cells (~80% confluency) and seed onto 15-cm plates at a density of 6-8 × 10^6 cells/plate. One 15-cm plate is sufficient for 6 to 8 transfections.

Trypsinize cells and resuspend in pre-warmed media to obtain a single cell suspension. Pool cells into a 15-ml tube.

Spin down cells at 1000 rpm for 5 minutes. Remove supernatant.

Resuspend cells in PBS. Repeat step 3.

Resuspend cells in a HM buffer to a final concentration of 2 × 10^7 cells/ml.

Combine 100 μl of the cell suspension with the plasmid cocktail in an eppendorf tube. Mix well. Transfer the mixture to a Gene Pulser Cuvette, 0.2-cm electrode gap (Bio-Rad Catalog No 165-2086).

Transfect cells with an Amaxa nucleofector II (program A-024).

Immediately add 500-μl pre-warmed medium into the cuvette.

Mix and transfer cells from the cuvette to a 6-cm dish with pre-warmed medium

2.5 Selection and recovery of single colonies (estimated time: ~2 weeks)

Hygromycin selection

48 hours post nucleofection, split cells from each 6-cm plate into two 10-cm plates with fresh media containing hygromycin at a final concentration of 200 μg/ml.

-

Refresh hygromycin-containing media every 2 days until colonies appear (usually 8-10 days post nucleofection).

Targeting efficiency: HygR colonies should be obtained at a much higher frequency with the 3-plasmid cocktail than from controls (Figure 1B), suggesting efficient targeting. The estimated targeting frequency is ~1 × 10^-3.

Pick single colonies with a pipetman and transfer into wells of a 96-well plate.

When clones grow to confluency, trypsinize the 96-well plate in 30 μl of trypsin solution and split to two 96-well plates. The plate with the 2:1 ratio split is used for genotyping (see below), and the other plate with the 4:1 split is used for further cell expansion.

2.6 Genotyping

Cells were grown to confluence in the new 96-well plate (from step 4 in section 2.5). Media was removed and cells washed 2x with PBS. Following washes, cells were lysed in plate by the addition of 40 μl lysis buffer (10 mM Tris pH 8, 0.45% NP40, 0.45% Tween 20, 100 μg/ml Proteinase K), followed by incubation at 55 °C for 2 hours, and then 95 °C for 5 minutes to inactivate the Proteinase K. Genotyping was performed with 0.5 μl cell lysate in a 12.5 μl PCR reaction (OneTaq system, NEB Catalog No M0480L).

PCR primers

m53bp1-check-5′-F: 5′-GAATGGGCGATCCGATATTGCG m53bp1-check-3′-R: 5′-CATCCTGATATGCATAAGACACTG Hygro-internal-F: 5′-GTATCACTGGCAAACTGTGATGG Hygro-internal-R: 5′-CCATCACAGTTTGCCAGTGATAC Universal-F: 5′- CTGAGAAAGTGCTAAGAGCG Universal-R: 5′- ACCTTTCTGTGGGTGAGAAC

PCR program

95 °C, 2 minute

95 °C, 30 seconds

60 °C, 60 seconds

68 °C, 2 minute

Repeat steps 2-4 33 times

68 °C, 5 minutes

12 °C, holding temperature

3. Results

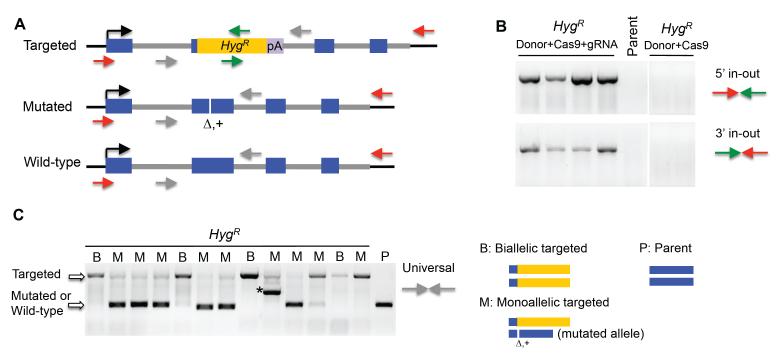

Targeting events were verified by PCR with one primer within the marker gene and one outside of either of the homology arms (Figure 3A), termed 5′ in-out and 3′ in-out PCR, respectively (Figure 3B). The two in-out PCR reactions only amplify from the correctly targeted allele, but not from the wild-type allele, such that clones producing positive signals in both in-out reactions were diagnosed as correctly targeted.

Figure 3.

Genotyping targeted clones.

(A) Diagram of genotyping PCR. The primers outside of the homology arms and inside the selection marker are shown as red and green arrows, respectively, while the universal primers within the homology arms are shown as grey arrows. In-out PCR reactions can only amplify from the targeted allele, while universal PCR reactions amplify the targeted, mutated and wild-type alleles.

(B-C) Representative PCRs from a targeting experiment of the 53BP1 gene.

(B) Most HygR clones recovered from transfection with donor and Cas9/gRNA showed the correct inout PCR fragments while the parental cells and clones recovered from control transfection without gRNA did not give an amplification product. In the absence of gRNA expression, HygR clones are not successfully targeted.

(C) Some HygR clones only showed the larger amplification product expected for the targeted allele and are predicted to be targeted at both alleles (B, biallelic targeted), whereas others showed both the targeted PCR product and a smaller fragment corresponding to the wild-type or mutated allele (M, monoallelic targeted). DNA sequencing showed the smaller fragment often contained deletion or insertion mutations (Δ,+), the majority of which were frameshifts. Asterisk, a mutated allele containing an insertion that generated a significantly larger sized product compared to the wild-type allele.

Targeted clones were subjected to further genotyping to determine if monoallelic or biallelic gene targeting occurred, using the two “universal” primers that lie within the homology arms (gray arrows, Figure 3A). This universal PCR reaction amplifies from both targeted and non-targeted alleles, generating products with easily distinguishable sizes. Targeted clones that only showed the targeted PCR band are likely to be biallelic targeted (B); whereas those that showed the targeted PCR band and an approximately wild-type PCR band are likely monoallelic targeted (M) (Figure 3C).

Notably, if an allele undergoes Cas9/gRNA-mediated cleavage and is repaired without using the donor (i.e., by NHEJ), small mutations such as deletions and insertions that do not significantly alter the size of the universal PCR product (as compared to that from the wild-type allele) can occur. Thus, monoallelic targeted clones may actually contain a second non-functional allele. To test this hypothesis, the universal PCR product from the non-targeted allele was sequenced. In all cases analyzed, mutations were found in the non-targeted allele (Figure 3C), many of which were frame-shifts that disrupt the target gene. Thus, in addition to the biallelic targeted clones, those monoallelic targeted clones with a frameshift mutation in the second allele are also biallelic knockouts. Overall, ~90% clones recovered from hygromycin selection were monoallelic or biallelic targeted (83/93), a large majority of which were biallelic knockouts (76%, 71/93): 29% biallelic targeted (27/93) and 47% monoallelic targeted with a mutated allele (44/93). Western blotting confirmed these results (data not shown, in another manuscript under preparation).

4. Troubleshooting and alternative approaches

The Cas9-mediated gene targeting strategy described here is based on activation of a promoterless marker upon homologous integration of the donor fragment. However, if transfection of the donor plasmid without Cas9/gRNA gives rise to a similar number of colonies as transfection of the donor+Cas9/gRNA, it suggests that the marker can be efficiently expressed without homologous integration, such that a redesign of the donor plasmid should be considered to eliminate residual promoter activity.

Conversely, the inability to activate the marker by homologous integration could point to a problem expressing the marker as a fusion protein. We have successfully targeted two other genes with the approach described here, so Hyg may be a particularly amenable marker for 5′ fusions. For markers that may be inactive as part of a fusion protein, a bicistronic donor can be constructed. For example, a 2A self-cleaving sequence (e.g., [33]) can be inserted upstream of the marker. However, we used this strategy with the fluorescence marker mRuby2 to target a key catalytic site of the structure-specific endonuclease Gen1 and found that the percentage and the mean fluorescence intensity of mRuby2-positive cells from transfection of the donor+Cas9/gRNA were very low and similar to the negative control (omitting the gRNA). We infer that the lack of mRuby expression is due to low expression of the endogenous gene, because we were able to recover correctly targeted clones at low efficiency (~10%, including some biallelic targeted clones), yet they did not have detectable fluorescence. Thus, while selection is not absolutely necessary to recover gene-targeted clones, it clearly enhances the efficiency of their recovery.

Cas9-mediated gene disruption can also be accomplished through two alternative routes: 1) error-prone NHEJ leading to frame-shift mutations (no homologous donor) and 2) gene targeting with a short homologous single-stranded DNA oligo that, for example, contains a novel restriction site. Both approaches have been shown to be effective in mouse cells [34], and have the benefit that construction of a donor plasmid is not required. However, utilizing a selectable marker has several advantages. First, gene disruption without selection depends on high cleavage efficiency by Cas9/gRNA, otherwise screening for disrupted clones among a large background of wild-type (and monoallelic mutant) clones is tedious. Thus, optimal gRNA(s) need to be identified by Surveyor or T7 endonuclease assay. Second, since a variety of repair events are possible from error-prone NHEJ, a number of cell clones need to be genotyped to determine which ones have the desired biallelic frameshift mutations. In this case, genotyping requires molecular cloning of multiple PCR products from each cell clone to ensure that both alleles are genotyped. (We typically sequence ten Topo-cloned products from each cell clone.) Using a single-stranded donor fragment which tags the locus with a restriction site ameliorates these issues; however, we have found this approach to be less efficient than using a selectable marker, especially in non-transformed human cells. Third, if disruption of a gene results a growth disadvantage, targeted clones will be underrepresented in the unselected population and thus difficult to recover/identify. These concerns are minimized, if not eliminated, by a selectable marker, as a defined mutation is created and one can semi-quantitatively determine how successful targeting is by simply scoring the number of colonies after selection (Figure 1B): an increase with the donor Cas9/gRNA-mediated cleavage indicates effective targeting, and the larger the increase, the more efficient the targeting.

The main disadvantage of the strategy described here is that disruption of essential genes cannot be obtained. The inability to obtain biallelic targeting may indicate that a gene is essential, but this conclusion can only be definitively reached by creating a conditional allele. The Cas9 system has been used to target loxP sites to generate conditional alleles in mice [35]; such approaches can also be applied to ES cells. A “pre-emptive” complementation strategy can also be used [36], especially in cases where a structure-function analysis of a protein is desired. In this case, a transgene which expresses the protein under investigation (or variants thereof) is first introduced into cells; the GOI is then subjected to the targeting strategy described here. If transgene expression is required to support biallelic targeting, then it can be concluded that the gene is essential.

Despite the advantages of this strategy, some concerns have been raised about the specificity of Cas9. Off-target effects can be reduced by judicious selection of the Cas9/gRNA target sequence. An alternative approach uses Cas9 nickases. Unlike wild-type Cas9 that cleaves both DNA strands, Cas9 nickases create single-strand breaks. Paired Cas9 nickases that generate nearby single-strand breaks in opposite DNA strands (and hence a DSB) can efficiently stimulate gene targeting, while the chance for off-target activity is significantly reduced because two 19 bp sequences are unlikely to be present in sufficient proximity at other genomic locations [27, 28].

5. Conclusions

Our Cas9-mediated gene targeting strategy represents several advantages compared to traditional gene targeting approaches: first and most important, biallelic targeting/knockout is achieved with high efficiency by just one round of targeting; second, a single selection marker is used, providing more options for knocking out additional genes with other markers; third, the homology arms of the donor are much shorter in Cas9-mediated gene targeting (~800 bp) compared to those in traditional gene targeting approaches (up to several kb), making it easier to construct the donor plasmid and to genotype the clones recovered from selection; fourth, monoallelic targeting without mutation of the second allele can be obtained at a lower frequency from the same targeting experiment as biallelic targeting, providing otherwise isogenic cell lines for comparing phenotypes in future studies.

6. Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (Y.Z.), American-Italian Cancer Foundation (F.V.), Dutch Cancer Society (P.M.K.), National Research Service Award Postdoctoral Fellowship F32GM084637 (J.R.L.), and NIH grant R01GM054668 (M.J.).

Appendix

Point 1. Annotated sequence of 53BP1 exon 2

Color coding: end of left homology arm, 19nt gRNA sequence, PAM sequence (TGG), sequence deleted by gene targeting.

GGGAGCAGATGGACCCTACTGGAAGTCAATTGGATTCAGATTTCTCTCAGCAAGACACTCCTTGCCTGATAAT AGAAGATTCTCAGCCTGAAAGCCAGGTTCTGGAAGAAGATGCAGGCTCTCACTTCAGCGTGCTATCTCGACA CCTTCCTAATCTGCAGATGCACAAAGAGAACCCCGTGTTG

Point 2. Annotated sequence of the 53BP1 donor fragment

Color coding: restriction sites for cloning, 53BP1 homology arms (coding sequence underlined), hygromycin marker, andBGH pA. Note that 177 bp of exon 2 are replaced with the Hyg-pA sequence.

ApaI - Exon1 - Intron1-2 - Exon2 - BglII

GGGCCCTGACGGGAAAAGGGGGAGCTCGCGGCCAGTGGCGGCGGTGGCGACAGTGGCGACCTGGGGATCGA CCTGGAGGGGCCTGGGCAGCGTGCAGAAACCTCTAGATCCAGCGCGAGGCACCTCTCGCCGGGATGCCAGGT AGTGCTGCGAGCGGAGCCGAGCTAGCGGGCCGCAGAGGCCCGGGTGGCGGGCTTGAAGGGCTGGCCGCCTG GAGGGGGCGGGGTGGCAAGCATGGCGGCGGTGACGGGGACGGGGTTGGAGGGCCGGGGAGGGGGTGGGGA GGCAGCCGCCGCGGTGGTCCTGAGGCCGCATGAGGGCCGTGGGCTTCCCGCCCGCCGGGGTTGCGAAGAGGT CTTCCCGGGGCTCAGTGGCGTCAGAACGCGGGGAGAGTTGTGTGGGGGATGGAAAGGGGCGGGGAGAAGAG GTGAGGAAGGAAGCGTGTCTGAGGGAAGGTGAAGAGAAAGGAGGGAGGGAGGGGGAGATCGAAGGATCCA GAGGCGCGGTGGTAAATAACGGAGAAATGAGGGCTGGGGAGATGGCTGAGAAAGTGCTAAGAGCGATTGCA AATGTGGGCTACTGGGTAGCCCTAGAATGGTCCCTTTCTCGATCTCACACTTCCGCCCCTTTATTTAGTCTCAG ATTGTGTGTGGAAAGCTCAATAGGGTTACTCTTCGAACTGATCTTTTGTTATTCCATTCCAGGGGAGCAGATG AGATCT

Hyg-XhoI-pA

AAAAAGCCTGAACTCACCGCGACGTCTGTCGAGAAGTTTCTGATCGAAAAGTTCGACAGCGTGTCCGACCTG ATGCAGCTCTCGGAGGGCGAAGAATCTCGTGCTTTCAGCTTCGATGTAGGAGGGCGTGGATATGTCCTGCGG GTAAATAGCTGCGCCGATGGTTTCTACAAAGATCGTTATGTTTATCGGCACTTTGCATCGGCCGCGCTCCCGA TTCCGGAAGTGCTTGACATTGGGGAATTCAGCGAGAGCCTGACCTATTGCATCTCCCGCCGTGCACAGGGTGT CACGTTGCAAGACCTGCCTGAAACCGAACTGCCCGCTGTTCTGCAGCCGGTCGCGGAGGCCATGGATGCGAT CGCTGCGGCCGATCTTAGCCAGACGAGCGGGTTCGGCCCATTCGGACCGCAAGGAATCGGTCAATACACTAC ATGGCGTGATTTCATATGCGCGATTGCTGATCCCCATGTGTATCACTGGCAAACTGTGATGGACGACACCGTC AGTGCGTCCGTCGCGCAGGCTCTCGATGAGCTGATGCTTTGGGCCGAGGACTGCCCCGAAGTCCGGCACCTC GTGCACGCGGATTTCGGCTCCAACAATGTCCTGACGGACAATGGCCGCATAACAGCGGTCATTGACTGGAGC GAGGCGATGTTCGGGGATTCCCAATACGAGGTCGCCAACATCTTCTTCTGGAGGCCGTGGTTGGCTTGTATGG AGCAGCAGACGCGCTACTTCGAGCGGAGGCATCCGGAGCTTGCAGGATCGCCGCGGCTCCGGGCGTATATGC TCCGCATTGGTCTTGACCAACTCTATCAGAGCTTGGTTGACGGCAATTTCGATGATGCAGCTTGGGCGCAGGG TCGATGCGACGCAATCGTCCGATCCGGAGCCGGGACTGTCGGGCGTACACAAATCGCCCGCAGAAGCGCGGC CGTCTGGACCGATGGCTGTGTAGAAGTACTCGCCGATAGTGGAAACCGACGCCCCAGCACTCGTCCGAGGGC AAAGGAATAGCTCGAGGCCTCGACTGTGCCTTCTAGTTGCCAGCCATCTGTTGTTTGCCCCTCCCCCGTGCCT TCCTTGACCCTGGAAGGTGCCACTCCCACTGTCCTTTCCTAATAAAATGAGGAAATTGCATCGCATTGTCTGA GTAGGTGTCATTCTATTCTGGGGGGTGGGGTGGGGCAGGACAGCAAGGGGGAGGATTGGGAAGACAATAGC AGGCATGCTGGGGATGCGGTGGGCTCTA

BglII - Intron2-3 - Exon3 - Intron3-4 - Exon4 - Intron4-5 - NotI

AGATCT

GTGAGTGAGTGATGATGCCCTGTTCAAGTTATTATTTTTTTCTGACCCCCCTACACCAAACTAACCCAGAAAA TTAACGTGTTTAGTTGATTGTTAGCTTTTGGATAAAGTTGGTGGGGAACGAAAAATGAAATCAACGTGTTCTC ACCCACAGAAAGGTCCCTGTTGTACTACTTTGTGTACTGTGAGGATCTTATGTGCTCATGTTTTCTAG GATATTGTATCAAATCCGGAACAATCTGCTGTAGAACAAGGAGACAGTAATAGCTCATTCAATGAACATCTG AAAGAAAAGAAAGCTTCAGGTGAGCAGTTGAAGGCTTGGCTCTCTGCAGTGTTTAAGGTCCTGTGGGGGCAG AACGATTTAAACATGCAGTTGAGATTATGTGTAAGGAAGCCTAGTTTGTTATCTAGTGTTCAGTAAGCCTTTG GATACCCGTGATTAGTTTGGTGTTGCCTCCATTTCTCAATTTGTATTAAAATTTGATGGCAAATGTCTTCTGTG CTAATATCCACCTCCTTCTGTCTTTTTCAGATCCTGTGGAGTCTTCTCATTTGGGTACCAGTGGTTCCATCAGT CAGGTCATTGAACGGTTACCTCAGCCAAACAGGACAAGCAGGTAAACTATTGTTTCAGTCAAAGGAGTTGAT TTCAATTTACTATTCGATCGACTCTTATCTGTACCTGCTGATTCATCCCAAAGATAAAGATATTAATCTTGTTT TGTGAATTGGGGAGTGGGATTTGGGGATTCTATAGGTAGTTCTGTTTTAGGACTGAGAGCTGGGATCTCTTTT GTGAAGTAACACTTCGTTCAACTCCTACAACTTCAAGCGGCCGC

7. Citations

- [1].Capecchi MR. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:507–512. doi: 10.1038/nrg1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jasin M, Berg P. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1353–1363. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.11.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sedivy JM, Sharp PA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:227–231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].te Riele H, Maandag ER, Clarke A, Hooper M, Berns A. Nature. 1990;348:649–651. doi: 10.1038/348649a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jasin M, Elledge SJ, Davis RW, Berg P. Genes Dev. 1990;4:157–166. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Szostak JW, Orr-Weaver TL, Rothstein RJ, Stahl FW. Cell. 1983;33:25–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90331-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jasin M, Rothstein R. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rouet P, Smih F, Jasin M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:6064–6068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rouet P, Smih F, Jasin M. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:8096–8106. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Choulika A, Perrin A, Dujon B, Nicolas JF. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1968–1973. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Smih F, Rouet P, Romanienko PJ, Jasin M. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:5012–5019. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.24.5012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Richardson C, Moynahan ME, Jasin M. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3831–3842. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.24.3831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Elliott B, Richardson C, Winderbaum J, Nickoloff JA, Jasin M. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:93–101. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Donoho G, Jasin M, Berg P. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4070–4078. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lieber MR. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:181–211. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.093131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Jasin M. Trends Genet. 1996;12:224–228. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Urnov FD, Miller JC, Lee YL, Beausejour CM, Rock JM, Augustus S, Jamieson AC, Porteus MH, Gregory PD, Holmes MC. Nature. 2005;435:646–651. doi: 10.1038/nature03556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Joung JK, Sander JD. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:49–55. doi: 10.1038/nrm3486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mali P, Esvelt KM, Church GM. Nat Methods. 2013;10:957–963. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, Zhang F. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Orlando SJ, Santiago Y, DeKelver RC, Freyvert Y, Boydston EA, Moehle EA, Choi VM, Gopalan SM, Lou JF, Li J, Miller JC, Holmes MC, Gregory PD, Urnov FD, Cost GJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e152. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Morales JC, Xia Z, Lu T, Aldrich MB, Wang B, Rosales C, Kellems RE, Hittelman WN, Elledge SJ, Carpenter PB. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14971–14977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212484200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Church GM. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Niwa H, Yamamura K, Miyazaki J. Gene. 1991;108:193–199. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90434-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Chen CM, Krohn J, Bhattacharya S, Davies B. PloS one. 2011;6:e23376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mali P, Aach J, Stranges PB, Esvelt KM, Moosburner M, Kosuri S, Yang L, Church GM. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:833–838. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ran FA, Hsu PD, Lin CY, Gootenberg JS, Konermann S, Trevino AE, Scott DA, Inoue A, Matoba S, Zhang Y, Zhang F. Cell. 2013;154:1380–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cho SW, Kim S, Kim Y, Kweon J, Kim HS, Bae S, Kim JS. Genome Res. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- [30].Guschin DY, Waite AJ, Katibah GE, Miller JC, Holmes MC, Rebar EJ. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;649:247–256. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-753-2_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kim HJ, Lee HJ, Kim H, Cho SW, Kim JS. Genome Res. 2009;19:1279–1288. doi: 10.1101/gr.089417.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pierce AJ, Jasin M. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;291:373–384. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-840-4:373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Carey BW, Markoulaki S, Hanna J, Saha K, Gao Q, Mitalipova M, Jaenisch R. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:157–162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811426106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wang H, Yang H, Shivalila CS, Dawlaty MM, Cheng AW, Zhang F, Jaenisch R. Cell. 2013;153:910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yang H, Wang H, Shivalila CS, Cheng AW, Shi L, Jaenisch R. Cell. 2013;154:1370–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Simsek D, Furda A, Gao Y, Artus J, Brunet E, Hadjantonakis AK, Van Houten B, Shuman S, McKinnon PJ, Jasin M. Nature. 2011;471:245–248. doi: 10.1038/nature09794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]