Abstract

Evidence for natural selection, positive or negative, on gene encoding antigens may indicate variation or functional constraints that are immunologically relevant. Most malaria surface antigens with high genetic diversity have been reported to be under positive-diversifying selection. However, antigens with limited genetic variation are usually ignored in terms of the role that natural selection may have in generating such patterns. We investigated orthologous genes encoding two merozoite proteins, MSP8 and MSP10, among several mammalian Plasmodium spp. These antigens, together with MSP1, are among the few MSPs that have two epidermal growth factor-like domains (EGF) at the C-terminal. Those EGF are relatively conserved (low levels of genetic polymorphism) and have been proposed to act as ligands during the invasion of RBCs. We use several evolutionary genetic methods to detect patterns consistent with natural selection acting on MSP8 and MSP10 orthologs in the human parasites P. falciparum and P. vivax, as well as closely related malarial species found in non-human primates (NHPs). Overall, these antigens have low polymorphism in the human parasites in comparison with the orthologs from other Plasmodium species. We found that the MSP10 gene polymorphism in P. falciparum only harbor non-synonymous substitutions, a pattern consistent with a gene under positive selection. Evidence of purifying selection was found on the polymorphism observed in both orthologs from P. cynomolgi, a non-human primate parasite closely related to P. vivax, but it was not conclusive in the human parasite. Yet, using phylogenetic base approaches, we found evidence for purifying selection on both MSP8 and MSP10 in the lineage leading to P. vivax. Such antigens evolving under strong functional constraints could become valuable vaccine candidates. We discuss how comparative approaches could allow detecting patterns consistent with negative selection even when there is low polymorphism in the extant populations.

Keywords: Plasmodium, negative selection, MSP-8, MSP-10, Plasmodium vivax, malaria vaccine antigen, epidermal growth factor-like domains

1. Introduction

Malaria is a serious, and sometimes fatal, human vector borne disease. It is caused by four species of parasitic protozoa from the genus Plasmodium: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale and P. malariae, with P. falciparum and P. vivax being associated with most malaria mortality and morbidity (Phillips, 2001; Price et al., 2007). Whereas new anti-malarial drugs are offering hope for malaria control and eradication, an effective vaccine against the two main Plasmodium species will ensure the sustainability of those efforts. Immunization with blood-stage antigens has been shown to be protective in a number of animal models using different antigens. At present, the leading blood-stage vaccine candidates are all proteins expressed during the invasion of the red blood cells (RBCs), either contained within the apical organelles or located on the merozoite surface (Richards and Beeson, 2009, Alaro et al., 2010). However, one of the challenges in developing vaccines targeting these antigens is overcoming their genetic diversity.

Indeed, most of the genes encoding blood stage antigens show substantial polymorphism, among them are those identified as merozoite surface proteins (MSP1 to MSP10). These variable antigens are usually found to be under positive (balancing) selection (Weedall and Conway, 2010) and they are considered important in the onset of acquired natural immunity. Such relatively high polymorphism, the argument follows, is explained by the accumulation of amino acid replacements that allow the parasite to evade the host immune response (Escalante et al., 2004; Weedall and Conway 2010). However, polymorphic regions are not evenly distributed across antigenic proteins and some merozoite proteins appear to be conserved (Richards and Beeson et al., 2009). Although protein sequence conservation may indicate negative (purifying) selection, there is a paucity of studies ascertaining such processes. Antigens with fragments under negative selection may offer valuable targets for antimalarial vaccines if protective immune responses could be elicited against those conserved targets since they are expected to be under functional constraints. As an example of conserved motifs, some of the merozoite surface proteins (e.g. msp1, msp2, msp4, msp5, msp8, and msp10) contain one or two copies of an epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domain at the carboxyl terminal that are anchored to the membrane via glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) membrane anchor (Gerold et al., 1996; Marshall et al., 1997, 1998; Black et al., 2001, 2003). These EGF-like domains consist of six cysteine residues and a motif first identified in human epidermal growth factor. Although their function remains unclear (Gaur et al. 2004); this motif has been associated not only with growth promotion, but more commonly with protein-protein recognition in merozoites and gametocytes, control functions or ion binding (Kansas et al., 1994; Perez-Leal et al., 2004). Given their potential importance, these motifs are considered putative vaccine candidates against malarial parasites.

In this investigation, we study the genetic diversity of orthologous genes encoding the MSP8 and MSP10 in several Plasmodium species. Like msp1, both proteins have a hydrophobic signal sequence in the N-terminal (residues 1-20), and a hypothetical GPI binding sequence and two EGF-like domains located at the C-terminal. Both proteins are cleaved during the red blood cell invasion in a similar way to MSP1 (Black et al., 2001, Black et al., 2003). Nevertheless, the function of msp8 and msp10 still remains unknown. We study how natural selection may have shaped the genetic diversity observed in the GPI-anchor EGF-like domain and the overall evolution of orthologous genes encoding these antigens in Plasmodium spp., focusing on the two major human malarial parasites (P. falciparum and P. vivax) and their closely related species found in non-human primates (NHPs). The use of comparative approaches allows for evaluating not only the processes maintaining the variation of a given vaccine candidate within species, but also provide an additional criterion for identifying functional constraints whenever conserved regions across species are observed. Both genes show low levels of genetic polymorphism when compared with other merozoite proteins. We found evidence indicating that P. falciparum and P. vivax could be under different selective pressures in the orthologs encoding msp10.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Parasite strains

In order to infer the history and processes involved in the evolution of the observed polymorphism in MSP8 and MSP10 genes, DNA was extracted from blood samples using QIAamp® DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). We processed samples from different geographic locations, increasing the probability of sampling the most divergent alleles. In the case of P. vivax, in addition to the Salvador I strain (XM_001613135) and VCG-1 (AY743238) available in GenBank for MSP8 and the Salvador I strain (AY587775) for MSP10, we sequenced both genes in ten laboratory isolates (Brazil I, Chesson from New Guinea, India VII, Indonesia I, Mauritania I, Rio Meta from Colombia, Sumatra, Thailand III, Vietnam Palo Alto, and Vietnam II). These sequences were compared with seven from different isolates of P. cynomolgi (P. c. ceylonensis, strain B, Cambodian, Gombak, Mulligan, PT1, and RO; see Coatney et al., 1971) and 12 sequences from isolates of P. inui (Celebes II, Hackeri, Hawking, Leaf Monkey II, Leucosphyrus, Mulligan, N-34, OS from India, Perlis, Philippine, Taiwan I and II; see Coatney et al., 1971). In addition, we also include one sequence from P. simiovale (Sri Lanka), one sequence for P. fieldi (N-3 from Malaysia), one sequence for P. coatneyi, five sequences for P. knowlesi (H, Hackeri, Malayan, Nuri, and Phillipine strains; see Coatney et al., 1971), and two strains of P. fragile (Sri Lanka and Nilgiri). All strains used in this study were provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In the case of P. falciparum, we use the sequences previously reported in the literature (Black et al., 2001; Black et al., 2003). In order to estimate the MSP8 and MSP10 phylogenies, we also included the published sequence in PlasmoDB (Aurrecoechea et al. 2009) for ortholog genes from P. reichenowi and the three rodent malaria parasites. In the case of MSP8, we use the sequence from P. reichenowi indentified as Pr_3502696.c000026330 Contig1; we also use the orthologs from P. bergei strain Anka (PBANKA_110220), the sequence PCHAS_110190 for P. chabaudi chabaudi, and the sequence for P. yoelii yoelii strain 17XNL (PY06415 or XM_721972). In the case of MSP10, we include the following sequences: P. reichenowi (Pr_3502696.c000026330.Contig1), P. chabaudi chabaudi (PCHAS_111910) and P. yoelii yoelii strain 17XNL (PY04226 or XM_719398).

2.2. PCR amplification, cloning and sequencing

MSP8 and MSP10 genes for P. vivax and the closely related malarial species found in non-human primates (NHPs) were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Amplification reactions were carried out in a 50μl volume and included 20 ng/μl of total genomic DNA, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1 × PCR buffer, 1.25 mM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.4 mM of each primer, and 0.03 U/μM of AmpliTaq ® DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Roche-USA). In order to amplify MSP8 and MSP10, specific degenerate primers were designed using previous sequences reported for P. vivax (Salvador I strain) and P. knowlesi (H strain). The primer forward 5′ AAG CRA MAA TGA RGA AAA ACG C and reverse 5′ GAA CAG RTA CAR GCA CAA AAG were used to amplify the MSP8 gene, and forward 5′ TTT TCG SAT GAA CAG GCA AG and reverse 5′ CTA AAA AAG AAA CTT GTG GAG for MSP10. The PCR conditions for amplifying both genes were: a partial denaturation at 94°C for 4 min and 35 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 53-59°C, and 2 min extension at 72°C, and a final extension of 10 min was added in the last cycle.

The amplified products for both genes were purified, cloned using the pGEM® -T easy Vector Systems I from Promega (USA), and sequenced using an Applied Biosystems 3730 capillary sequencer. Both strands were sequenced from at least two or three clones. The sequences reported in this study are deposited in GenBank, for MSP8 under the accession numbers JQ245976 to JQ246010 and for MSP10 with the numbers JQ286352 to JQ286393.

2.3. Evolutionary genetic analyses

Independent alignments for proteins and nucleotides were made for both genes using ClustalX version 2.0.12 with manual editing. One alignment was made using partial protein sequences for all Plasmodium species, and another using the nucleotide sequences for P. vivax and closely related species found in non-human primates. We performed phylogenetic analyses on both protein and nucleotide sequences for the two alignments. In the case of nucleotides, the gene phylogenies were first estimated by using the Neighbor-Joining methods (Saitou and Nei, 1987) with the Kimura 2-parameters model as implemented in MEGA 5 (Tamura et al., 2011). The reliability of the nodes in the NJ trees was assessed by bootstrap method with 1000 pseudo-replications (Nei and Kumar, 2000). Additionally, Bayesian phylogenetic analyses were performed as implemented in MrBayes version 3.1.2 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003). In the case of nucleotide sequences we used a General Time Reversible (GTR) + G and Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) + G model for protein sequences. In all Bayesian analyses, proteins or DNA, we used 5,000,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) steps, sampling was performed every 100 generations and discarded the 60% as a burn-in for a total of 20,000 trees used to estimate the posterior probability at each node. Mixing of the chain and convergence was properly checked after runs.

We explored the genetic polymorphism within each species by using the parameter π that estimates the average number of substitutions between any two sequences. In order to assess the effect of natural selection, we calculated the average number of synonymous (Ds) and non-synonymous substitutions (Dn) between a pair of sequences. The average number of Ds and Dn was estimated using Nei and Gojobori's method (Nei and Kumar, 1986) with the Jukes and Cantor correction as implemented in MEGA program (Kumar et al., 2001). In addition, we estimated the difference between Ds and Dn, and the standard deviation was calculated using bootstrap with 1000 pseudo-replications for Ds and Dn, as well as a two tailed Z-test on the difference between Ds and Dn (Nei and Kumar, 2000). The null hypothesis is that Ds=Dn; thus, we assumed as a null hypothesis that the observed polymorphism was neutral.

The assumption of neutrality was also tested in P. vivax and closely related species found in non-human primates by using the McDonald and Kreitman test (McDonald and Kreitman, 1991), which compares the intra- and inter-specific number of synonymous and non-synonymous sites. Significance was assessed using a Fisher's exact test for the 2 × 2 contingency table as implemented in the DnaSP program version 5.10.01 (Rozas et al., 2003). In this analysis, we compared the following species for both MSP8 and MSP10: P. falciparum with P. reichenowi; P. vivax with P. cynomolgi; P. inui, P. fieldi, and P. knowlesi; P. inui with P. fieldi and P. knowlesi; and P. fieldi with P. knowlesi.

Finally, in the case of P. vivax and related species, we explored the long term effect of selection using maximum likelihood approaches as implemented in HyPhy (Pond et al., 2005). Specifically, the ratio of kA to kS (= ω), in which kA and kS are the number of nonsynonymous and synonymous changes per nonsynonymous and synonymous sites, respectively, was estimated for branches in the phylogenetic trees estimated for each antigen using the branch model implemented in HyPhy. The ω ratio measures the direction and magnitude of selection on amino acid replacements, with values of ω < 1, ω = 1, and ω > 1 indicating purifying selection, neutral evolution, and positive selection, respectively. The heterogeneity of ω among branches was incorporated using the free-ratio model where each branch has its independent ω value. HyPhy was run using a codon partition, MG94 substitution model. We performed a likelihood ratio test comparing our null model – the P. vivax branch was constrained to having an omega of 1 – against our alternative model in which the branch was undergoing some form of selection (positive or negative). The models were compared using a likelihood ratio test (LRT). Since the tree topology affects the ω values, we explored the robustness of our results by performing a second set of tests where both antigens were studied using the same phylogeny estimated from mitochondrial genomes (Pacheco et al 2011).

3. Results

3.1. Description of MSP8 and MSP10 orthologs in Plasmodium spp

MSP8 and MSP10 are smaller in P. vivax and closely related species than their orthologs in P. falciparum. In the case of MSP8, Pfmsp8 is a 596-604 amino acid protein encoded by a single 1788-1812 bp exon gene whereas in P. vivax and the closely related parasites is a 476-487aa protein. Likewise, PfMSP10 is a single 1545-1575 bp exon gene encoding a 515-525 amino acid protein whereas in P. vivax and the closely related malarial species it is smaller (379-489aa).

In the case of MSP8, a relatively conserved hydrophobic signal sequence at the N-terminal (residues 1-20) followed by an asparagine-rich domain was identified in all the species studied. Similar to a number of other malaria antigens, this protein is asparagine-rich, with an average of 20.03% for P. falciparum-P. reichenowi and 13.83% for P. vivax and closely related species. Likewise, In MSP10 we identified a relatively conserved hydrophobic signal sequence at the N-terminal (residues 1-20) in all the species studied. This protein is also asparagine-rich, with an average of 17.13% for P. falciparum-P. reichenowi and 9.16% for P. vivax and closely related species. In Pfmsp8 and Pfmsp10, we identified tandem repeats or low complexity regions that are not present in the P. vivax orthologs or its closely related species. Indeed, the asparagine repeat observed in Pfmsp8 is not observed in P. vivax. Likewise, we observed eight degenerate 6-mer tandem repeats with the (N/I)EN(I/V/N)EN sequence located at the N-terminal of Pfmsp10 (Black et al., 2003); however, we could not identify any tandem repeat in P. vivax and closely related species.

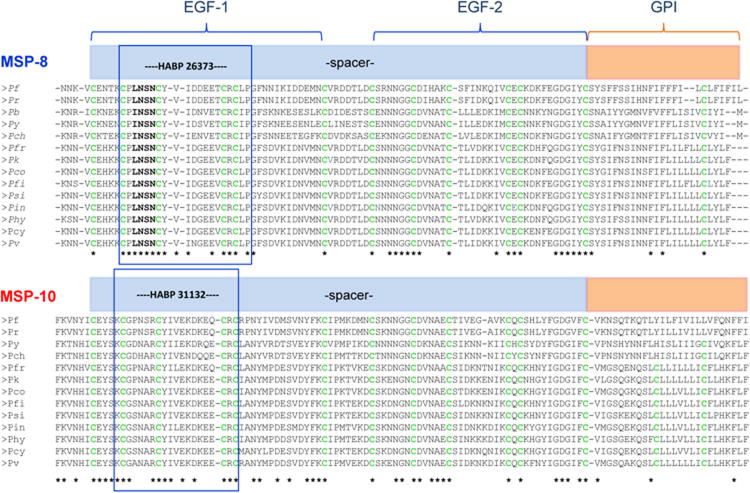

Figure 1 shows the EGF-like domains' alignment for msp8 and msp10 proteins in Plasmodium spp. In all the species, we could identify a hypothetical GPI binding sequence and the two EGF-like regions located in the C-terminal for both genes. It is worth nothing that all msp8 displayed a relatively high degree of conservation in both EGF-like motifs among Plasmodium spp. (Fig.1). As in previous reports, we found 15 cysteine residues in P. falciparum and 16 in P. vivax and closely related species, with 12 of them conserved between species and presumably being involved in forming disulfide bridges for EGF-like domains (Fig.1). In MSP10, we found 13 cysteine residues in Pfmsp10 and 14 in Pvmsp10 and closely related species, with the 12 of them conserved across the species and between msp8 and msp10 EGF-like domains. It is worth noting that, like MSP8, all MSP10 orthologs genes are relatively conserved in both EGF-like motifs across the Plasmodium spp. (Fig.1), but, outside of these domains, (hydrophobic signal peptide at the N-terminal and GPI and EGF-like domains at the C-terminal) msp8 and msp10 had little similarity among Plasmodium spp. orthologs.

Figure 1.

Alignment of the hypothetical GPI binding sequence and two EGF-like domains located at the C-terminal for orthologs genes that encode MSP8 and MSP10 in different Plasmodium species. The * indicates conserved residues among Plasmodium species within each gene. Cysteines are highlighted in green. HABP 26373 (CPLNSNCYVIDDEETCRCLP) in msp8 and HABP 31132 (KCGPNSRCYIVEKDKEQCRC) in msp10 correspond to the high activity binding peptides sequences (HABPS) able to specifically bind to red blood cells (RBCs) and are indicated for each gene with a blue frame. The species names are abbreviated as follow: Pf, P. falciparum; Pr, P. reichenowi; Pb, P. berghei; Py, P. yoelii; Pch, P. chabaudi chabaudi; Pfr, P. fragile; Pk, P. knowlesi; Pco, P. coatneyi; Pfi, P. fieldi; Psi, P. simiovale; Pin, P. inui; Phy, P. hylobati; Pcy, P. cynomolgi; and Pv, P. vivax.

Five high activity binding peptides (HABP) have been previously described in Pfmsp8, however, we only found one peptide conserved among all the Plasmodium species: HABP 26373. This HABP is located at the EGF-like domain at the C-terminal (Fig. 1). Identifying critical amino acids in HABP interaction with the red blood cell membrane have been shown to be a tool for designing immunogenic and protective molecules, contributing towards developing synthetic antimalarial vaccines (Purmova et al., 2002). In the case of Pf-HABP 26373, critical residues were identified: 501CPLNSNCYVIDDEETCRCLP520 (Puentes et al., 2003). We found that these critical residues are highly conserved across the species, observing only one single residue change in rodent malarias (INSN instead of LNSN, Fig. 1).

In the case of Pfmsp10, there are only three high activity binding peptides (HABP) that have been described (Puentes et al., 2005), and only one is conserved among all the Plasmodium species (HABPs 31132), and presented some homology with msp8 HABP 26373 (Fig.1). Msp10 similarities in structural features to both msp8 and msp1 EGF-like domains and in the high activity binding peptides (HABPs 31132) suggest that the tridimensional structure could be playing an important role in the red blood cell invasion.

3.2. Genetic diversity in MSP8 and MSP10 genes and phylogenetic analyses

Only six amino acid substitutions were found along the whole Pvmsp8 protein when we compared all the sequences against P. vivax Strain Salvador I; however, we identified more amino acid substitutions in P. cynomolgi and P. inui msp8 proteins (19 and 30 amino acids respectively). Table 1 describes the genetic variation found in non-EGF-like and EGF-like domains in MSP8 across Plasmodium species. The very low genetic diversity found in PfMSP8 was comparable to the diversity observed in P. vivax (π of 0.0026 vs. 0.0022). When we compared the genetic diversity found in the MSP8 orthologs from non-human primate malarias with the genetic diversity observed in PvMSP8 and PfMSP8, we found that they were an order of magnitude lower in the human parasites. Specifically, the MSP8 orthologous genes in P. cynomolgi and P. inui have a higher diversity than the other Plasmodium species (Table 1). The same pattern was found when we compared the genetic diversity of the non-EGF-like and EGF-like domains.

Table 1.

Polymorphism found in the gene encoding MSP8 in Plasmodium spp.

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSP-8 | ∏ (SE) | Ds | Dn | Ds-Dn (SD.) | p (Z-stat) |

| P. falciparum (n=7) | |||||

| Gene | 0.0026 (0.0007) | 0.0036 | 0.0024 | 0.0012 (0.0019) | 0.5425 (-0.6108) Ds = Dn |

| Non-EGF-like domains | 0.0032 (0.0008) | 0.0045 | 0.003 | 0.0016 (0.0023) | 0.4963 (-0.6817) Ds = Dn |

| EGF-like domains | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 (0.00) Ds = Dn |

|

| |||||

| P. vivax (n=11) | |||||

| Gene | 0.0022 (0.0007) | 0.0054 | 0.0015 | 0.0039 (0.0023) | 0.0849 (-1.7375) Ds = Dn |

| Non-EGF-like domains | 0.0014 (0.0007) | 0.0017 | 0.0013 | 0.0004 (0.0014) | 0.7774 (-0.2834) Ds = Dn |

| EGF-like domains | 0.0052 (0.0020) | 0.0176 | 0.0021 | 0.0155 (0.0093) | 0.0824 (-1.7513) Ds = Dn |

|

| |||||

| P. cynomolgi (n=7) | |||||

| Gene | 0.0119 (0.0016) | 0.0418 | 0.0054 | 0.0365 (0.0073) | 0.00 (-4.8432) Ds > Dn |

| Non-EGF-like domains | 0.0125 (0.0019) | 0.0408 | 0.0066 | 0.0343 (0.0084) | 0.00008 (-4.0787)Ds > Dn |

| EGF-like domains | 0.0096 (0.0030) | 0.0452 | 0.0011 | 0.0441 (0.0161) | 0.0065 (-2.7693) Ds > Dn |

|

| |||||

| P. inui (n=8) | |||||

| Gene | 0.0114 (0.0015) | 0.0259 | 0.0081 | 0.0178 (0.0055) | 0.0012 (-3.3071) Ds > Dn |

| Non-EGF-like domains | 0.0116 (0.0017) | 0.0210 | 0.0095 | 0.0114 (0.0051) | 0.0357 (-2.1242) Ds > Dn |

| EGF-like domains | 0.0109 (0.0035) | 0.0423 | 0.0033 | 0.0390 (0.0143) | 0.0119 (-2.5530) Ds > Dn |

|

| |||||

| P. knowlesi (n=5) | |||||

| Gene | 0.0039 (0.0011) | 0.0109 | 0.0023 | 0.0086 (0.0043) | 0.0416 (-2.0594) Ds > Dn |

| Non-EGF-like domains | 0.0033 (0.0011) | 0.0048 | 0.0029 | 0.0019 (0.0036) | 0.5985 (-0.5279) Ds = Dn |

| EGF-like domains | 0.0061 (0.0031) | 0.0304 | 0 | 0.0304 (0.0151) | 0.0646 (-1.8653) Ds = Dn |

|

| |||||

| P. fragile (n=2) | |||||

| Gene | 0.0049 (0.0018) | 0.0036 | 0.0052 | -0.0016 (0.0043) | |

| Non-EGF-like domains | 0.0054 (0.0022) | 0.0048 | 0.0056 | -0.0009 (0.0053) | |

| EGF-like domains | 0.0031 (0.0029) | 0 | 0.0039 | -0.0039 (0.0042) | |

In order to determine whether the observed polymorphism in MSP-8 was under natural selection, we explored the number of synonymous (Ds) and the non-synonymous (Dn) substitutions in each species (Table 1). We found more synonymous than non-synonymous changes per site in both human parasites P. falciparum (n=7) and P. vivax (n=11); however, those differences were not significant using a Z-test (Table 1, Nei and Kumar, 2000). A similar pattern was observed on MSP8 orthologs in non-human primate parasites. In this case, however, we were able to detect a statistically significant (p < 0.05) excess of synonymous versus non-synonymous substitutions (Table 1). This pattern of more synonymous over non-synonymous substitutions could indicate negative (purifying) selection acting on this gene, especially on non-human primate malarial parasites. In addition, we checked the number of SNPs reported for this gene in P. falciparum in PlasmoDB (Aurrecoechea et al 2009) and found that eight have been reported, five non-synonymous and three synonymous. Whereas we cannot directly relate the reported SNPs with Dn and Ds comparisons (not all the SNPs have been tested in all the strains reported so pairwise comparisons are not possible); MSP8 have synonymous substitutions even when non correction for multiple substitutions is used.

Moreover, we found only nine amino acid substitutions along the whole Pvmsp10 protein when we compared all the sequences against P. vivax Salvador I strain. Table 2 shows the genetic diversity found in MSP10 non-EGF-like and EGF-like domains across the Plasmodium species. Like MSP8, the low genetic diversity found in PfMSP10 was similar to the observed in PvMSP10 (π of 0.0020 vs. 0.0033) and comparable with the PfMSP8 and PvMSP8 polymorphism (π of 0.0026 vs. 0.0022 respectively). Indeed, when we compared MSP10 orthologs from non-human primate malarias, the genetic diversity observed in PvMSP10 and PfMSP10 was also an order of magnitude lower. Additionally, in P. cynomolgi and P. inui, the MSP10 orthologous genes have higher diversity than the other Plasmodium species (Table 2). Unlike MSP8, the MSP10 EGF-like domains in all the species of Plasmodium (except P. falciparum) were less polymorphic that the non-EGF-like domains and also when compared with the whole gene (Table 2).

Table 2.

Polymorphism found in the gene encoding MSP10 in Plasmodium spp.

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSP-10 | ∏ (SE) | Ds | Dn | Ds-Dn (SD.) | p (Z-stat) |

| P. falciparum (n=13) | |||||

| Gene | 0.0020 (0.0007) | 0 | 0.0025 | -0.0025 (0.0009) | 0.0046 (2.8846) Ds < Dn |

| Non-EGF-like domains | 0.0019 (0.0008) | 0 | 0.0024 | -0.0024 (0.0009) | 0.0083 (2.6853) Ds < Dn |

| EGF-like domains | 0.0023 (0.00165) | 0 | 0.0030 | -0.0030 (0.0020) | 0.1324 (1.5151) Ds = Dn |

|

| |||||

| P. vivax (n=11) | |||||

| Gene | 0.0033 (0.0008) | 0.0073 | 0.0022 | 0.0051 (0.0031) | 0.0695 (-1.8314) Ds = Dn |

| Non-EGF-like domains | 0.0035 (0.0011) | 0.0064 | 0.0027 | 0.0037 (0.0036) | 0.2838 (-1.0768) Ds = Dn |

| EGF-like domains | 0.0026 (0.0012) | 0.0103 | 0.0007 | 0.0097 (0.0053) | 0.0554 (-1.9344) Ds = Dn |

|

| |||||

| P. cynomolgi (n=7) | |||||

| Gene | 0.0526 (0.0038) | 0.0788 | 0.0495 | 0.0293 (0.0126) | 0.0260 (-2.2539) Ds > Dn |

| Non-EGF-like domains | 0.0621 (0.0045) | 0.0774 | 0.0629 | 0.0145 (0.0141) | 0.3051 (-1.0300) Ds = Dn |

| EGF-like domains | 0.0236 (0.0052) | 0.0838 | 0.0104 | 0.0734 (0.0259) | 0.0063 (-2.7820) Ds > Dn |

|

| |||||

| P. inui (n=8) | |||||

| Gene | 0.0223 (0.0021) | 0.0284 | 0.0212 | 0.0071 (0.0051) | 0.1526 (-1.4394) Ds = Dn |

| Non-EGF-like domains | 0.0265 (0.0025) | 0.0314 | 0.0259 | 0.0055 (0.0060) | 0.3479 (-0.9422) Ds = Dn |

| EGF-like domains | 0.0094 (0.0028) | 0.0187 | 0.0073 | 0.0114 (0.0098) | 0.2612 (-1.1288) Ds = Dn |

|

| |||||

| P. knowlesi (n=5) | |||||

| Gene | 0.0195 (0.0028) | 0.0299 | 0.0172 | 0.0127 (0.0080) | 0.0941 (-1.6875) Ds = Dn |

| Non-EGF-like domains | 0.0261 (0.0036) | 0.0381 | 0.0237 | 0.0144 (0.0107) | 0.1757 (-1.3620) Ds = Dn |

| EGF-like domains | 0.0017 (0.0017) | 0.0084 | 0 | 0.0084 (0.0086) | 0.3109 (-1.0176) Ds = Dn |

|

| |||||

| P. fragile (n=2) | |||||

| Gene | 0.0125 (0.0032) | 0.0120 | 0.0128 | -0.0008 (0.0078) | |

| Non-EGF-like domains | 0.0152 (0.0040) | 0.0111 | 0.0165 | -0.0055 (0.0090) | |

| EGF-like domains | 0.0058 (0.0038) | 0.0144 | 0.0037 | 0.0108 (0.0153) | |

When we estimated the number of synonymous (Ds) and the non-synonymous (Dn) substitutions for MSP10 in each species (Table 2), we found an excess of non-synonymous versus synonymous substitutions in P. falciparum, a difference that is significant using a two-tailed Z test (n=13, Table 2). Indeed we found zero synonymous substitutions (Table 2). We checked the number of SNPs reported in PlasmoDB for this gene and found nine, all of them non-synonymous on 12 additional isolates. We could not incorporate them in our analyses because not all the SNPs have been tested in all the isolates. The fact that there is not a single synonymous substitution may indicate that PfMSP10 could be under positive selection. In contrast, PvMSP10 showed more synonymous that non-synonymous substitutions; however, such differences were not statistically significant. The orthologous gene in P. cynomolgi, PcyMSP10, also showed more synonymous than non-synonymous substitutions, but in this case, Ds>Dn was significant indicating that MSP10 could be under negative (purifying) selection in this non-human primate (Table 2). More synonymous than non-synonymous substitutions were also observed in MSP10 orthologs found in other non-human primate parasites (P. inui and P. knowlesi), but such differences were not significant.

The assumption of neutrality was further tested in all Plasmodium MSP8 and MSP10 orthologs by using the McDonald and Kreitman test (McDonald and Kreitman, 1991). The results for MSP8 are summarized in Table 3. When we compared the genetic variation of MSP8 in P. falciparum with P. reichenowi, and P. vivax to closely related species found in macaques, we found no evidence indicating that natural selection is acting on PfMSP8 and PvMSP8. However, there was an overall excess of synonymous over non-synonymous substitutions in the P. cynomolgi polymorphism found in the whole gene and in the non-EGF-like domains when we compared it with P. inui, P. fieldi and P. knowlesi (Table 3). This pattern could be interpreted as evidence of negative (purifying) selection acting on PcyMSP8. In addition, when we compared the genetic variation of MSP10 in P. falciparum with P. reichenowi, and P. vivax to its closely related species, using the McDonald and Kreitman test (McDonald and Kreitman, 1991), we found no evidence indicating that natural selection is acting on MSP10 gene in any of the species studied (data not shown).

Table 3.

McDonal and Kreitman test (Neutrality Index) for gene encoding MSP8 in Plasmodium spp.

| MSP-8 | Gene | Non-EGF-like domains | EGF-like domains |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. falciparum vs. P. reichenowi | 1.300 (NS) | 0.889 (NS) | - |

| P. vivax vs. P. cynomolgi | 1.006 (NS) | 0.995 (NS) | 2.000 (NS) |

| P. vivax vs. P. inui | 1.694 (NS) | 1.905 (NS) | 2.333 (NS) |

| P. vivax vs. P. fieldi | 1.189 (NS) | 1.406 (NS) | 2.700 (NS) |

| P. vivax vs. P. knowlesi | 1.097 (NS) | 1.910 (NS) | 1.969 (NS) |

| P. cynomolgi vs. P.inui | 0.342 (P<0.005) | 0.339 (P<0.005) | 0.400 (NS) |

| P. cynomolgi vs. P. fieldi | 0.356 (P<0.005) | 0.400 (P<0.005) | 0.133 (NS) |

| P. cynomolgi vs. P. knowlesi | 0.404 (P<0.005) | 0.516 (NS) | 0.125 (NS) |

| P. inui vs. P. fieldi | 0.652 (NS) | 0.869 (NS) | 0.250 (NS) |

| P. inui vs. P. knowlesi | 0.901 (NS) | 1.135 (NS) | 2.000 (NS) |

| P. fieldi vs. P. knowlesi | 0.894 (NS) | 2.339 (NS) | 0.0 (NS) |

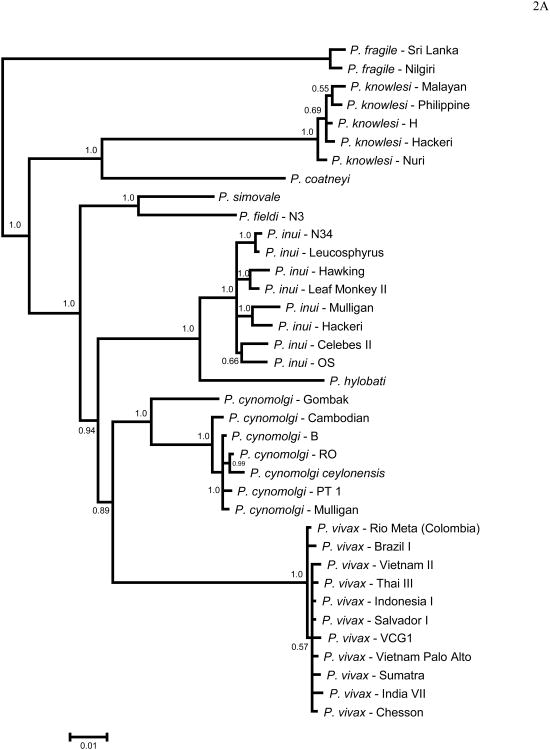

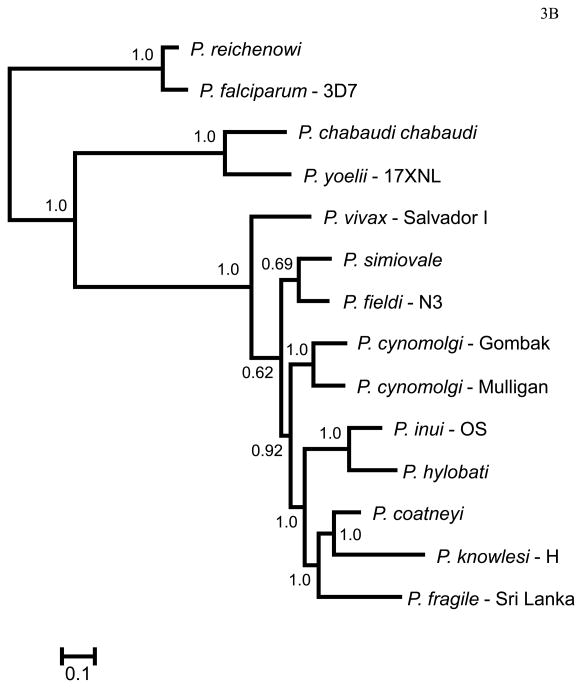

Figure 2 shows the phylogenies obtained in this study for MSP8 (Fig. 2A) and MSP10 (Fig. 2B), using DNA sequences including only P. vivax and closely related species. Overall, both phylogenies are compatible and consistent with previous reports using putatively neutral genes (Escalante et al., 1998a, 2005) or gene encoding merozoite antigens (MSP1, Pacheco et al. 2007; RAP1, Pacheco et al. 2010). As expected, in both phylogenies we found that P. vivax is part of a monophyletic group with closely related non-human malaria parasites found in Southeast Asia (Fig. 2). In addition, P. vivax, P. cynomolgi, P. inui, P. hylobati, P. simiovale and P. fieldi form a clade in both genes, with P. cynomolgi as a sister group of P. vivax in the case of MSP8, and P. simiovale and P. fieldi as a sister group of P. vivax in the case of MSP10. P. coatneyi appears in another clade sharing a recent common ancestor with P. knowlesi (Fig 2). It is worth noting that MSP8 and MSP10 phylogenies (Fig. 2 and 3) are not fully consistent, however, such incongruence is expected when we study single gene phylogenies using antigens. Nevertheless, given that both P. cynomolgi and P. vivax share a recent common ancestor, in this and previous studies, the use of P. cynomolgi in comparative evolutionary analyses with P. vivax is appropriate.

Figure 2.

Bayesian phylogenetic trees using DNA sequences of the gene encoding (A) MSP8 and (B) MSP10 using MrBayes. The number on nodes of the trees is posterior probabilities based on 5.000.000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) steps and the 60% discarded as a burn-in. Sampling was performed every 100 generations. The sequences reported in this study are identified with their species and strain names.

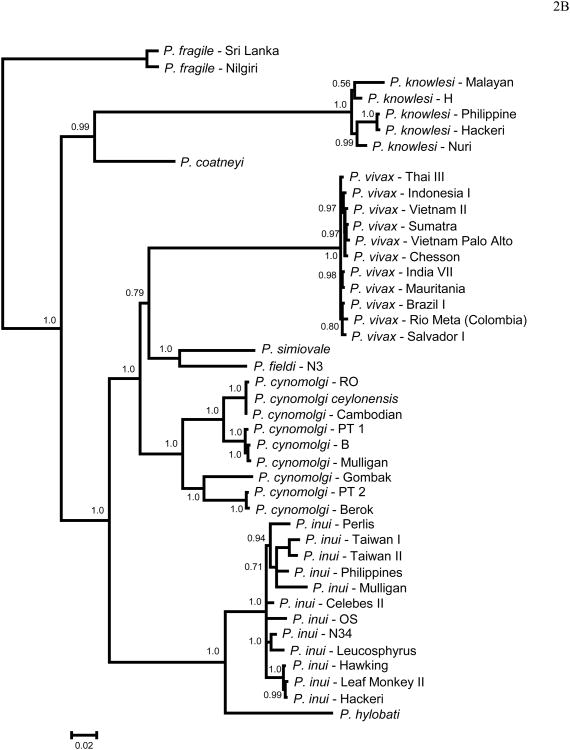

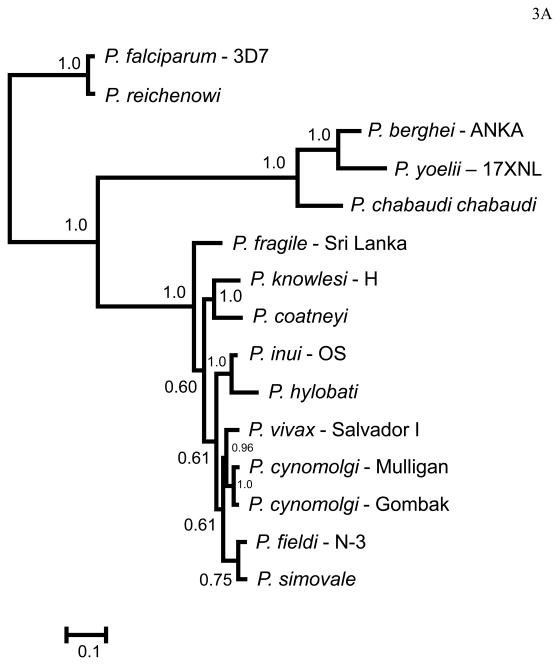

Figure 3.

Bayesian phylogenetic trees using protein sequences of the orthologs genes encoding (A) MSP8 and (B) MSP10 using MrBayes. The number on nodes of the trees is posterior probabilities based on 5.000.000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) steps and the 60% discarded as a burn-in. Sampling was performed every 100 generations. The sequences reported in this study are identified with their species and strain names.

In order to compare all Plasmodium species considered in this study, we estimated phylogenies obtained for MSP8 (Fig. 3A) and MSP10 (Fig.3B) using protein sequences. As expected, in both trees we found (1) that P. vivax and closely related non-human malaria parasites form a monophyletic group; (2) P. coatneyi form a clade with P. knowlesi, (3) all rodent malaria also form a monophyletic group, (4) and P. falciparum and P. reichenowi also form a monophyletic group3. The two protein phylogenies show differences in topology with the one obtained from MSP8 being similar to the one obtained from mitochondrial genomes (Pacheco et al 2011); however, phylogenies built on antigenic proteins may not reflect the phylogenetic relationships among species.

In order to explore whether natural selection may be acting on the divergence among MSP8 and MSP10 orthologs, we use phylogenetic base methods as implemented in HyPhy. We focused on P. vivax and its related parasites since we have enough closely related species with a similar GC content and there was enough similarity outside the EGF-like domains that allow the proper alignment among them at the nucleotide level. We used first the phylogenies derived from each antigen and found an overall omega lower than one (ω < 1) that is consistent with purifying selection acting on the divergence of this gene. Indeed, all branches leading to the extant Plasmodium species (P. vivax and related non-human primate malarias) showed values of ω < 1 with the branch leading to P. vivax having a value of 0.106 (CI: 0.060-0.151) for MSP8 and 0.431 (CI: 0.344-0.520) for MSP10 respectively. Given the differences in tree topologies between MSP8 and MSP10, we then compared the omega values observed in these genes using the same phylogeny derived from mitochondrial genes (Pacheco et al 2011). Likewise, the results of omegas lower than 1 on the P. vivax branches for MSP8 and MSP10 were significant showing that the results are robust regardless of changes in the tree topology. Specifically we found ω= 0.0111 (CI: 0.0652-0.1569) for the branch leading to PvMSP8 and ω=0.450 (CI: 0.361-0.54) for the branch leading to PvMSP10.

4. Discussion

The lack of a good vaccine candidate against human malarias is the result, at least in part, of the inherent complexities found in the parasite life cycle and its interactions with the human host. Among all proteins involved in the invasion of the red blood cell, MSPs comprise some of the best characterized proteins in P. falciparum and some of them are considered promising vaccine candidates due to their accessibility to interaction with host immune system molecules (Richards and Beeson, 2009). Comparative evolutionary studies have shown that several of these proteins are important in the host-parasite interaction (Escalante et al., 2004; Weedall and Conway, 2010). The focus of such studies has been the identification of genes with relatively high polymorphism that are suspected to be under positive (diversifying) selection; that is, genes which variation could be explained by the accumulation of amino acid replacements that may allow the parasite to evade the host immune response (Escalante et al., 2004; Weedall and Conway, 2010). The rational is that those protein polymorphisms could be important for the onset of natural immunity. However, there are only a handful of studies ascertaining how relatively conserved genes could be subject to natural selection, positive or negative, especially in P. vivax populations. In the case of antigens under negative (purifying) selection, they may offer valuable targets for antimalarial vaccines if protective immune responses could be elicited against them. Their value resides precisely on the fact that the parasite appears unable to accumulate polymorphism at the protein level, probably due to functional constraints. Unfortunately, on antigens with low polymorphism in natural populations, it is difficult to ascertain how selection could operate on them especially if we consider the complex demographic history of malarial parasites (Cornejo and Escalante 2006). However, the fact that malaria parasites in primates, including humans, shared their most recent common ancestor in a distant past allows us to infer patterns that may have prevailed during their evolutionary history. In this study, we have described the selective forces operating on the polymorphism and divergence observed in MSP8 and MSP10 genes using comparative approaches.

Our results confirmed the observation that both MSP8 and MSP10 genes have a very limited amount of genetic polymorphism in P. falciparum (Black et al., 2001, Black et al., 2003) and P. vivax (Table 1 and 2). A recent report also showed a very low genetic diversity (π of 0.0002) in 25 isolates of P. vivax from five different geographical regions in Colombia (Garzón-Ospina et al., 2011). Overall, when we compared the low polymorphism found in both MSP8 and MSP10 with other antigens studied, including MSP1 (Escalante et al., 1998b, Pacheco et al., 2007, Tanabe et al., 2007, Pacheco et al., 2010, Putaporntip et al., 2010), we can conclude that these antigens are the most conserved of the merozoite proteins identified to date. In the specific case of MSP10, some grade of polymorphism was only found in the non-EGF-like domain at the N-terminal in all the species of Plasmodium studied (Table 1 and 2). In addition to that, the EGF-like domains are highly conserved across Plasmodium species as evidenced in our alignment that includes both genes (Fig. 1). In that alignment we can see that EGF-like domains are conserved across all the species included in this study (Fig. 1). It has been suggested that the degree of conservation in both EGF-like motifs could be the result of maintaining functions during the red blood cell invasion (Drew et al., 2004, Perez-Leal et al., 2004), and/or these domains perform related or redundant roles in the parasite's life cycle, both within and between very divergent Plasmodium species. Indeed, studies on MSP119 have provided limited but compelling evidence indicating that the EFG-like domains found in merozoite proteins may have similar roles. Specifically, MSP119 maintains its function even after its EFG-like domain was replaced with the equivalent region of MSP8 (Drew et al., 2004). This “redundancy hypothesis” is further supported by the results of peptide binding studies showing that MSP8 and MSP1 have a common red blood cell binding regions (Puentes et al., 2003).

Regardless of their limited polymorphism, we have shown how MSP8 and MSP10 could be under different selective pressures in each species of malaria parasite. We found that all substitutions in Pfmsp10 were non-synonymous, suggesting that MSP10 in P. falciparum could be under positive selection; however, the polymorphisms in MSP8 and MSP10 in P. vivax and MSP8 in P. falciparum were consistent with expectations under neutrality. In contrast, we found evidence indicating negative (purifying) selection acting on orthologs genes encoding MSP8 in non-human primate malarias (P. cynomolgi, P. inui, and P. knowlesi). Although there is no information regarding the immunologic role played by these genes in non-human primate malarial parasites, negative selection may be acting on several putative malaria vaccine antigens that show low polymorphisms (e.g. RAP1, Pacheco et al., 2010).

Whereas we found no conclusive evidence of selection acting on the polymorphism of P. vivax (more synonymous changes were observed, but that difference was not significant), likely due to the limited sample size, our comparative analyses based on phylogenetic methods indicate that both MSP8 and MSP10 genes have diverged under strong negative (purifying) selection indicating functional constrains. This observation, together with the evidence for negative selection in closely related species, strongly suggests that negative selection is an important process in the P. vivax orthologs of these proteins that otherwise elicits an immune response. We could not use these comparative analyses in P. falciparum since there is no data from closely related species other than P. reichenowi.

The observation that these genes are under purifying selection, especially MSP8, could be explained by their different roles in the parasite's life cycle. In contrast to other MSP proteins (including MSP10), PfMSP8 is expressed predominantly during the first half of the P. falciparum erythrocytic cycle (8 to 16 h after invasion), and only the smaller C-terminal PfMSP8 is maintained until schizogony and appears to localize to the food vacuole. The absence of the PfMSP8 protein on the surface of invading merozoites suggests that PfMSP8 may not play a role in the parasite-red blood cell interactions during invasion in the case of P. falciparum (Black et al., 2005, Drew et al., 2005, Koning-Ward et al., 2008). Importantly, as both the MSP1 and MSP8 EGF-like domains are present in the ring stages, it is still possible that at this time they perform the same (or related) role in the establishment and functioning of the parasitophorous vacuole (Black et al., 2005, Drew et al., 2005, Koning-Ward et al., 2008). No information on the role of PvMSP8 is available.

Although there are clear functional differences among merozoite surface proteins with EFG-like domains, the putative functional redundancies of these domains appear to have practical applications in developing immunogenic and protective vaccine constructs. EGF-like domains found in MSP1 and MSP8 have been studied separately and/or together focusing on their ability to protect mice against P. yoelii malaria (Drew et al., 2004, Shi et al., 2007, Alaro et al., 2010). Those studies indicate that immunization with either MSP1 or MSP8 induces protection that is mediated primarily by antibodies against conformation-dependent epitopes (Shi et al., 2007). Recently, Alaro et al. (2010) found that immunization with rPyMSP1/8 vaccine, a construct designed by fusing PyMSP119 to the N-terminal of PyMSP8, elicited an MSP8-rectricted T cell response that was sufficient to provide help for both PyMSP119 and PyMSP8-specific B cell to produce substantial levels of protective antibodies. The significance of this result is that the immunogenicity of MSP119 is improved when coupled to MSP8 instead of MSP133, and the use of MSP8 as a fusion partner for MSP119 instead of heterologous GST or tetanus toxoid T cell epitopes provides an opportunity to boost vaccine-induced response by natural infection (Alaro et al., 2010). The fact that MSP8 is conserved among Plasmodium species and its divergence seems to be under strong purifying selection may allow for designing chimeras that incorporate MSP1 and MSP8 from divergent rodent malarial parasites. Such an approach could be a first step toward creating multi-species anti-malarial vaccine constructs.

Whereas very little is known about the immunogenicity and protection efficacy of MSP10 as a vaccine, there is evidence that shows strong immunogenicity, but no protection in immunized Aotus monkeys with a recombinant P. vivax MSP10 (Giraldo et al., 2010). Given that both MSP8 and MSP10 share structural features with proteins from the MSP family, especially with MSP1 (Black et al., 2003, Puentes et al., 2005,) and based on the highly conserved nature of their EGF-like domain across different species of Plasmodium, we suggest that not only MSP8, but also MSP10 should be explored in further development of chimeric vaccines with MSP1. Indeed, the evidence that these proteins are conserved due to the potential action of negative (purifying) selection during their evolutionary history provides additional support to their consideration as part of malaria vaccine formulations.

In summary, MSP8 and MSP10 orthologs genes are highly conserved in all Plasmodium spp. The conserved EGF-like domains in MSP-8 and 10, among Plasmodium species, could be related with function as ligands during the invasion of RBCs and/or with redundant roles in the parasite's life cycle. Although the polymorphism found in MSP10 for P. falciparum could be under positive selection, we have evidence of negative selection acting on MSP8 and MSP10 in P. vivax using phylogenetic base approaches. We also found evidence for negative selection acting on both genes in non-human primate malarias (P. cynomolgi, P. inui, and P. knowlesi). Overall, our capacity of interpreting the role played by selection on genes with low polymorphism in human malarias increases if they can be compared with the polymorphism and/or divergence of their closely related species.

We investigated genes encoding two merozoite proteins, MSP8 and MSP10 in Plasmodium spp.

Natural selection is operating differently in P. falciparum and P. vivax.

We found only non-synonymous polymorphism in PfMSP10 indicating positive selection

We found evidence for negative selection on P. vivax and related species.

Acknowledgments

AA Escalante is supported by the grant R01GM80586 from the National Institute of Health. AA Rahman was supported by a fellowship from the School of Life Sciences Undergraduate Research program at Arizona State University. We thank the DNA laboratory at the School of Life Sciences for their technical support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alaro JR, Lynch MM, Burns JM., Jr Protective immune responses elicited by immunization with a chimeric blood-stage malaria vaccine persist but are not boosted by Plasmodium yoelii challenge infection. Vaccine. 2010;28:6876–6884. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurrecoechea C, Brestelli J, Brunk BP, Dommer J, Fischer S, Gajria B, Gao X, Gingle A, Grant G, Harb OS, Heiges M, Innamorato F, Iodice J, Kissinger JC, Kraemer E, Li W, Miller JA, Nayak V, Pennington C, Pinney DF, Roos DS, Ross C, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Treatman C, Wang H. PlasmoDB: a functional genomic database for malaria parasites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D539–43. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black CG, Wu T, Wang L, Hibbs AR, Coppel RL. Merozoite surface protein 8 of Plasmodium falciparum contains two epidermal growth factor-like domains. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001;114:217–226. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black CG, Wang L, Wu T, Coppel RL. Apical location of a novel EGF-like domain-containing protein of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;127:59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(02)00308-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black CG, Wu T, Wang L, Topolska AE, Coppel RL. MSP8 is a non-essential merozoite surface protein in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2005;144:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatney RG, Collins WE, Warren M, Contacos PG. The Primate Malaria. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington D.C: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo OE, Escalante AA. The origin and age of Plasmodium vivax. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22:558–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew DR, O'Donnell RA, Smith BJ, Crabb BS. A common cross-species function for the double epidermal growth factor-like modules of the highly divergent Plasmodium surface proteins MSP-1 and MSP-8. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20147–2053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew DR, Sanders PR, Crabb BS. Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 8 is a ring-stage membrane protein that localizes to the parasitophorous vacuole of infected erythrocytes. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3912–3922. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.3912-3922.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escalante AA, Freeland DE, Collins WE, Lal AA. The evolution of primate malaria parasites based on the gene encoding cytochrome b from the linear mitochondrial genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998a;95:8124–8129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escalante AA, Lal AA, Ayala FJ. Genetic polymorphism and natural selection in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Genetics. 1998b;149:189–202. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.1.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escalante AA, Cornejo OE, Freeland DE, Poe AC, Durrego E, Collins WE, Lal AA. A monkey's tale: the origin of Plasmodium vivax as a human malaria parasite. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:1980–1985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409652102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escalante AA, Cornejo OE, Rojas A, Udhayakumar V, Lal AA. Assesing the effect of natural selection in malaria parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:388–395. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzón-Ospina D, Romero-Murillo L, Tobón LF, Patarroyo MA. Low genetic polymorphism of merozoite surface proteins 7 and 10 in Colombian Plasmodium vivax isolates. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:528–531. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaur D, Mayer DC, Miller LH. Parasite ligand-host receptor interactions during invasion of erythrocytes by Plasmodium merozoites. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:1413–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerold P, Schofield L, Blackman MJ, Holder AA, Schwarz RT. Structural analysis of the glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol membrane anchor of the merozoite surface proteins-1 and -2 of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;75:131–43. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)02518-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo MA, Arevalo-Pinzon G, Rojas-Caraballo J, Mongui A, Rodriguez R, Patarroyo MA. Vaccination with recombinant Plasmodium vivax MSP-10 formulated in different adjuvants induces strong immunogenicity but no protection. Vaccine. 2010;28:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansas GS, Saunders KB, Ley K, Zakrzewicz A, Gibson RM, Furie BC, Furie B, Tedder TF. A role for the epidermal growth factor-like domain of P-selectin in ligand recognition and cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:609–618. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Koning-Ward TF, Drew DR, Chesson JM, Beeson JG, Crabb BS. Truncation of Plasmodium berghei merozoite surface protein 8 does not affect in vivo blood-stage development. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008;159:69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Tamura K, Jakobsen IB, Nei M. MEGA2: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:1244–1245. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall VM, Silva A, Foley M, Cranmer S, Wang L, McColl DJ, Kemp DJ, Coppel RL. A second merozoite surface protein (MSP-4) of Plasmodium falciparum that contains an epidermal growth factor-like domain. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4460–4467. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4460-4467.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall VM, Tieqiao W, Coppel RL. Close linkage of three merozoite surface protein genes on chromosome 2 of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;94:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JH, Kreitman M. Adaptive protein evolution at the Adh locus in Drosophila. Nature. 1991;351:652–654. doi: 10.1038/351652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M, Kumar S. Simple methods for estimating the number of synonymous and nosynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol Biol Evol. 1986;3:418–426. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M, Kumar S. Molecular evolution and phylogenetics. Oxford University Press; NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco MA, Battistuzzi FU, Junge RE, Cornejo OE, Williams CV, Landau I, Rabetafikam L, Snounou G, Jones-Engel L, Escalante AA. Timing the origin of human malarias: the lemur puzzle. BMC Evol Biol. 2011;11:299. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco MA, Poe AC, Collins WE, Lal AA, Tanabe K, Kariuki SK, Udhayakumar V, Escalante AA. A comparative study of the genetic diversity of the 42 kDa fragment of the merozoite surface protein 1 in Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax. Infect Genet Evol. 2007;7:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco MA, Ryan EM, Poe AC, Basco L, Udhayakumar V, Collins WE, Escalante AA. Evidence for negative selection on the gene encoding rhoptry-associated protein 1 (RAP-1) in Plasmodium spp. Infect Genet Evol. 2010;10:655–661. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Leal O, Sierra AY, Barrero CA, Moncada C, Martínez P, Cortes J, López Y, Torres E, Salazar LM, Patarroyo MA. Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein 8 cloning, expression, and characterisation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324:1393–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RS. Current status of malaria and potential for control. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:208–226. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.1.208-226.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pond SL, Frost SD, Muse SV. HyPhy: hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:676–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RN, Tjitra E, Guerra CA, Yeung S, White NJ, Anstey NM. Vivax malaria: neglected and not benign. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:79–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puentes A, García J, Ocampo M, Rodríguez L, Vera R, Curtidor H, López R, Suarez J, Valbuena J, Vanegas M, Guzman F, Tovar D, Patarroyo ME. P. falciparum: merozoite surface protein-8 peptides bind specifically to human erythrocytes. Peptides. 2003;24:1015–23. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(03)00185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puentes A, Ocampo M, Rodríguez LE, Vera R, Valbuena J, Curtidor H, García J, López R, Tovar D, Cortes J, Rivera Z, Patarroyo ME. Identifying Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-10 human erythrocyte specific binding regions. Biochimie. 2005;87:461–472. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purmova J, Salazar LM, Espejo F, Torres MH, Cubillos M, Torres E, López Y, Rodríguez R, Patarroyo ME. NMR structure of Plasmodium falciparum malaria peptide correlates with protective immunity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1571:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putaporntip C, Udomsangpetch R, Pattanawong U, Cui L, Jongwutiwes S. Genetic diversity of the Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein-5 locus from diverse geographic origins. Gene. 2010;456:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JS, Beeson JG. The future for blood-stage vaccines against malaria. Immunol Cell Biol. 2009;87:377–390. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozas J, Sanchez-DelBarrio JC, Messeguer X, Rozas R. DnaSP DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2496–2497. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The Neighbor-Joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Lynch MM, Romero M, Burns JM., Jr Enhanced protection against malaria by a chimeric merozoite surface protein vaccine. Infect Immun. 2007;75:1349–1358. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01467-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using Maximum Likelihood, Evolutionary Distance, and Maximum Parsimony Methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe K, Escalante AA, Sakihama N, Honda M, Arisue N, Horii T, Culleton R, Hayakawa T, Hashimoto T, Longacre S, Pathirana S, Handunnett S, Kishino H. Recent independent evolution of MSP-1 polymorphism in Plasmodium vivax and related simian malaria parasites. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007;156:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weedall GD, Conway DJ. Detecting signatures of balancing selection to identify targets of anti-parasite immunity. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]