Abstract

Objectives:

We investigated the sleep structure of patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) and the association of abnormalities with brain lesions.

Methods:

This was a prospective cross-sectional study. Thirty-three patients with NMOSD and 20 matched healthy individuals were enrolled. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients were collected. Questionnaires were used to assess quality of sleep, daytime sleepiness, fatigue, and depression. Nocturnal polysomnography was performed.

Results:

Compared with healthy controls, patients with NMOSD had decreases in sleep efficiency (7%; p = 0.0341), non-REM sleep N3 (12%; p < 0.0001), and arousal index (6; p = 0.0138). REM sleep increased by 4% (p = 0.0423). There were correlations between arousal index and REM% or Epworth Sleepiness Scale (r = −0.0145; p = 0.0386, respectively). Six patients with NMOSD (18%, 5 without infratentorial lesions and 1 with infratentorial lesions) had a hypopnea index >5, and all of those with sleep apnea had predominantly the peripheral type. The periodic leg movement (PLM) index was higher in patients with NMOSD than in healthy controls (20 vs 2, p = 0.0457). Surprisingly, 77% of the patients with PLM manifested infratentorial lesions.

Conclusions:

Sleep architecture was markedly disrupted in patients with NMOSD. Surveillance of nocturnal symptoms and adequate symptomatic control are expected to improve the quality of life of patients with NMOSD.

Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is an inflammatory demyelinating condition of the CNS with a predilection for attacking the optic nerves and spinal cord. NMO spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is a term used to encompass NMO (with both optic neuritis and myelitis) and limited phenotypes such as recurrent optic neuritis or myelitis. The aquaporin-4 (AQP4) water channel, the presumed autoantigen in most patients with NMOSD, is found throughout the CNS but particularly in the optic nerve and spinal cord. In the brain, AQP4 is preferentially expressed in periventricular organ regions1,2 that are critically involved in the generation of sleep.3,4 A correlation was evident between brain abnormalities identified by MRI and AQP4 localizations in periependymal regions surrounding the third ventricle and cerebral aqueduct.1,2 Although cortical abnormality as revealed mostly by MRI studies5 is a matter of interest and controversy in NMOSD,6 other brain lesions can already be visualized in a substantial proportion of patients with NMOSD at the onset of disease.7 Possible brain involvement, particularly adjacent to ependymal regions surrounding the third ventricle and cerebral aqueduct, leads to a hypothesis that patients with NMOSD would have sleep disturbances. In this study, we aimed to characterize sleep patterns of patients with NMOSD using a full-night nocturnal polysomnography (PSG)-based approach focusing on (1) polysomnographic characteristics in NMOSD, and (2) polysomnographic characteristic variations associated with brain lesions. We then conducted a case-control study to compare PSG sleep aspects between patients with NMOSD and healthy controls.

METHODS

Study population.

This was a prospective study. The patients were enrolled based on the following criteria: (1) diagnosis of NMOSD, as defined by Wingerchuk et al. in 20078; (2) in a stable state; and (3) >18 years of age. Patients were excluded if they had (1) history of serious head trauma or neuropsychiatric disease; (2) dependence on psychoactive substances, such as alcohol; or (3) intake of hypnotic or sedative drugs during the preceding 2 weeks. Healthy controls were recruited to match the patients for age, sex, and body mass index. None of the patients had a history of neurologic and/or psychiatric disease or other significant medical conditions. From August 2013 to May 2014, 33 patients with NMOSD and 20 healthy controls who met the criteria were consecutively enrolled. The NMOSD group included 30 patients with NMO, and 3 patients with longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis with positive AQP4 antibodies (figure e-1 at Neurology.org/nn). Treating neurologists used the Expanded Disability Status Scale to assess current neurologic function at each visit. Serum AQP4 antibodies were tested with an in-house fluorescence-activated cell sorting assay, as described previously9 (details in appendix e-1), and subsequently verified by cell-based assay using the M23 isoform (Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany). 3T GE MR scanners were used with the standardized MRI protocol, including T1, T2, fast fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, and contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging of brain and spinal cord.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was approved by the Tianjin Medical University General Hospital Institutional Review Boards and Ethics Committee.

PSG examination.

Overnight video PSG examinations were performed for all participants using the sleep laboratory digital system (Nicolet v32, Natus Medical Incorporated, Pleasanton, CA). Participants were asked to sleep at their usual bedtimes.

All PSG sessions were monitored by trained technicians who scored the results visually according to standardized criteria.10 The following PSG sleep parameters were recorded and systematically evaluated: (1) total time in bed (TIB); (2) total sleep time (TST); (3) sleep efficiency (SE; the TST/TIB ratio expressed as a percentage); (4) sleep latency (SL; the length of time to sleep onset); (5) wake after sleep onset (WASO; the number of minutes of wakefulness after the onset of persistent sleep to the end of the PSG recording); (6) non-REM sleep stages 1, 2, and 3 and REM sleep stages N1, N2, N3, and REM; (7) the apnea-hypopnea index; (8) periodic leg movements (PLMs) per hour of sleep (PLMs/h >5 was used as the standard to indicate PLMs in sleep PSG; and (9) mean oxygen saturation Spo2 and nadir Spo2. These parameters were analyzed by a specialist in a blinded fashion before comparisons were made between groups. International Classification of Sleep Disorders-2 was used to diagnose and classify sleep abnormalities.11

Sleep questionnaires.

Sleep quality was measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). The Chinese version of the PSQI has an overall reliability coefficient of 0.82–0.83 and an acceptable test–retest reliability coefficient of 0.77–0.85.12 Sleepiness was measured by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS). The Chinese version of the ESS has satisfactory psychometric properties, and scores greater than 10 indicate sleepiness.13 Depression was measured by the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), and a total score of 20 or higher on the BDI-II was indicative of depression in the Chinese population.14 The Fatigue Questionnaire (FQ), which consists of 14 items that were tested for validity and reliability in a Chinese population,15 was used to measure physical and mental fatigue during the previous months.

Statistical analysis.

SPSS for Windows version 17.0 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for the statistical analyses. Two-sample t tests (for normal continuous data), Mann-Whitney tests (for discontinuous data), and χ2 tests (for dichotomized data) were used to compare baseline characteristics between patients with NMOSD and healthy controls. Questionnaire scores and PSG parameters of interest (SE, N1%, N2%, N3%, REM%, SL, arousal index, and apnea-hypopnea index) were tested by one-way analysis of variance accompanied by post hoc test. A difference between 2 groups regarding PLMs/h was analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test. Spearman correlation tests were used to examine associations between PSG parameters and ESS scores. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Due to the exploratory nature of this pilot study, no adjustment for multiple comparisons was made.

RESULTS

Baseline data for the patients with NMOSD.

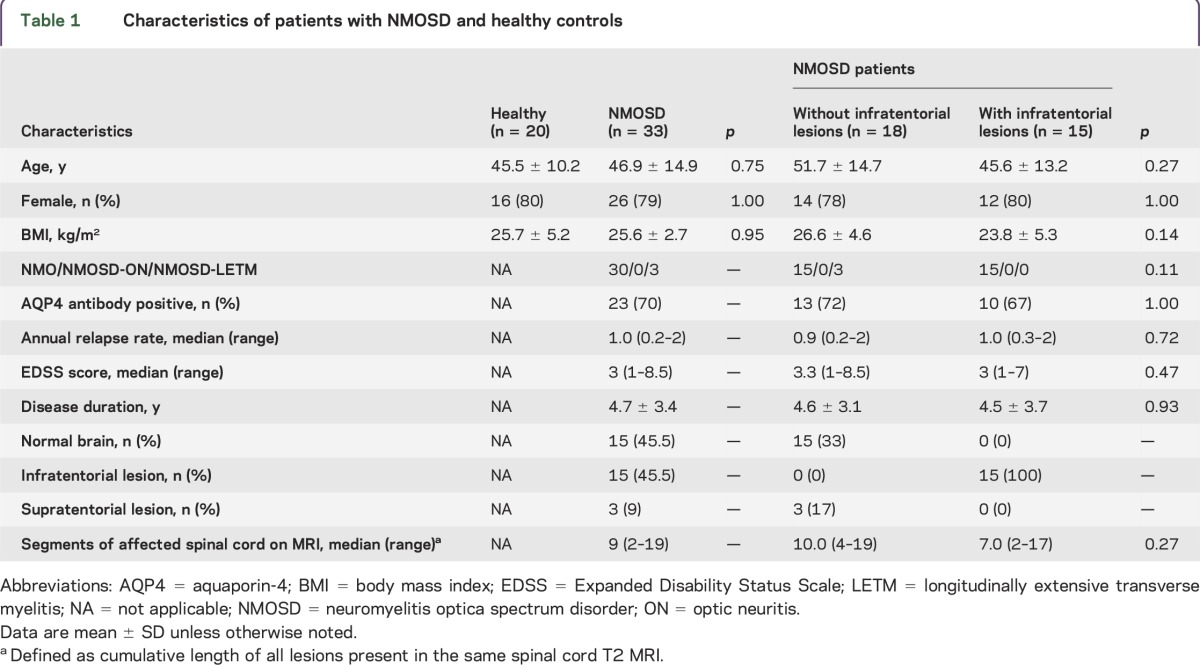

Baseline characteristics for patients with NMOSD and matched healthy controls are shown in table 1. The mean disease duration of patients with NMOSD was 4.7 years, and 23 of the 33 patients (70%) were positive for AQP4 antibodies. Among the patients with NMOSD, MRI analyses showed that 15 had no lesions in the brain, 15 had infratentorial lesions (3 patients with hypothalamic periventricular and brainstem lesions and 12 patients with only brainstem lesions) and 3 had supratentorial lesions. No patients were completely blind. The median number of affected spinal cord segments, defined as the cumulative length of all lesions present in the same spinal cord T2 MRI, was 9 (range 2–19). No significant differences with regard to involvement of spinal cord segments were noted between subgroups (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with NMOSD and healthy controls

Patients with NMOSD enrolled in this study were in remission. Due to special circumstances in China (i.e., fewer available disease-modifying medications and lack of insurance coverage),16 a large proportion of patients in this cohort did not receive medications while in remission. Twenty-seven of 33 had not taken any medication in the past 4 weeks, 5 of 33 received rituximab for 3–6 months and remained in remission, and 1 of 33 received bimonthly IV immunoglobulin treatment.

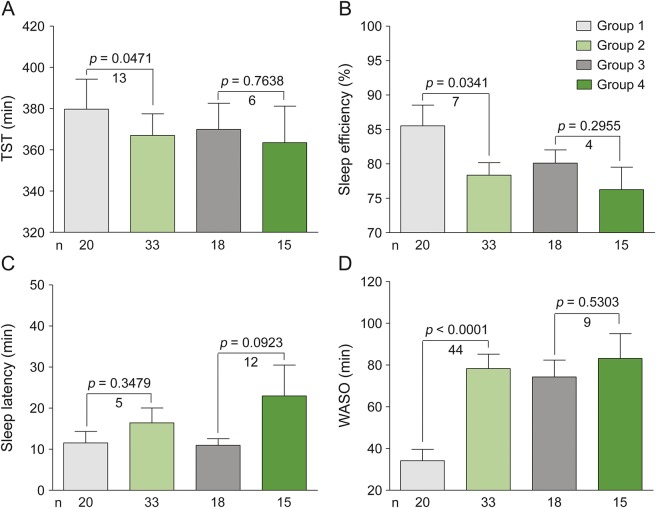

Decreased sleep quality in patients with NMOSD.

Compared with controls, patients with NMOSD had decreased levels of SE (79% vs 86%, p = 0.0341), a 13-minute decrease in TST (367 minutes vs 380 minutes, p = 0.0471), a 5-minute increase in SL (17 minutes vs 12 minutes, p = 0.3479), and a 44-minute increase in WASO (78 minutes vs 34 minutes, p < 0.0001) according to PSG assessment (figure 1, A–D).

Figure 1. Comparative analysis of sleep architecture by groups.

Patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) were divided into 4 groups and compared. Group 1: healthy controls, n = 20; group 2: patients with NMOSD, n = 33; group 3: NMOSD without infratentorial lesions, n = 18; group 4: NMOSD with infratentorial lesions, n = 15. Sleep quality categories are: (A) total sleep time (TST), (B) sleep efficiency (SE), (C) sleep latency (SL), and (D) wake time after sleep onset (WASO). TST, SE, SL, and WASO were tested by one-way analysis of variance accompanied by Bonferroni post hoc test; statistical significance is defined as p < 0.05.

Disturbed sleep structure in patients with NMOSD.

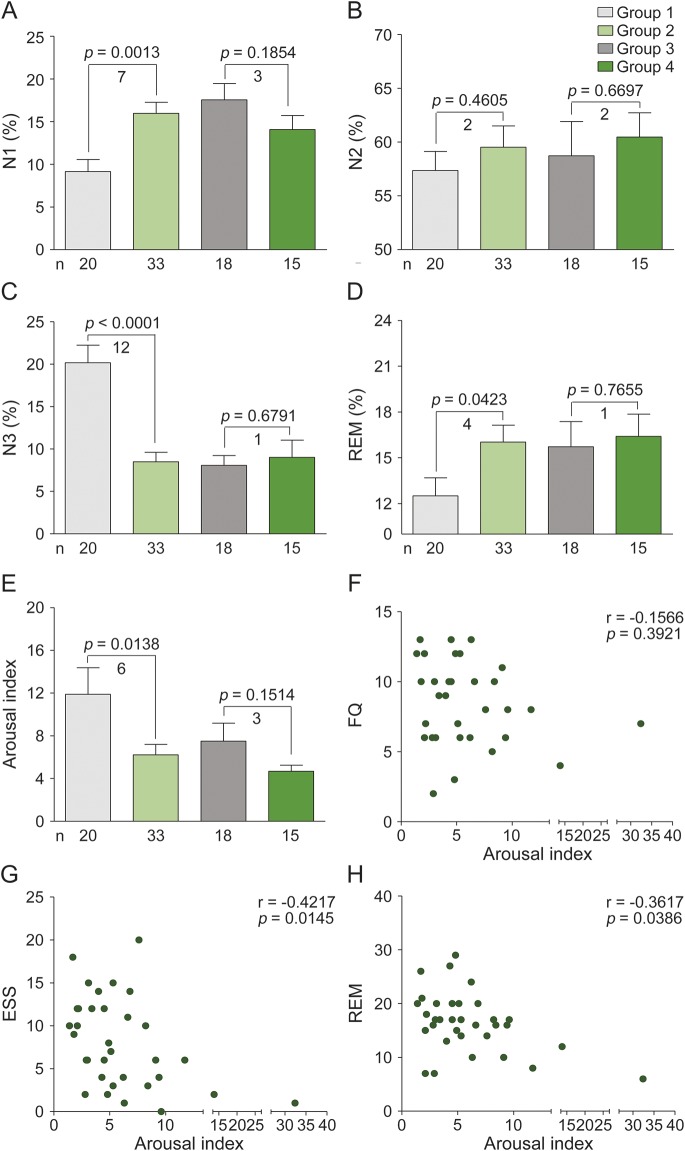

As figure 2, A–E depicts, compared with healthy controls, patients with NMOSD had a 12% decrease in N3 sleep (8% vs 20%, p < 0.0001), a 4% increase in REM sleep (16% vs 12%, p = 0.0423), and a 7% increase in N1 sleep (17% vs 10%, p = 0.0013). Durations of N2 sleep were similar for the 2 groups. Moreover, a decreased arousal index was found in patients with NMOSD compared to controls (6 vs 12, p = 0.0138). Fatigue scores were markedly higher in patients with NMOSD than in healthy controls (FQ 9.0 vs 5.4, p = 0.0009). However, there was no correlation between fatigue score and arousal index (r = −0.1566, p = 0.3921) (figure 2F) and no association between ESS and fatigue (r = 0.0080, p = 0.9660). However, scores for REM sleep and ESS were associated with arousal index by Spearman correlation tests (r = −0.4217, p = 0.0145; r = −0.3617, p = 0.0386, respectively) (figure 2, G and H).This result indicates that NMOSD patients with low arousal index experienced increases in REM during nocturnal sleep and felt drowsy during their daytime hours.

Figure 2. Comparison of sleep stages by groups and correlation analysis.

Graphs show the percentage of time patients spent in each sleep stage: non-REM sleep stages N1 (A), N2 (B), and N3 (C), and REM sleep stage (D). (E) Arousal index: the average number of arousals in a 1-hour period. (F) Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS). (G) Fatigue Questionnaire (FQ). Groups 1–4 are those cited in figure 1. (A–E) Comparison of sleep stages and arousal index by group. (F–H) Arousal index with FQ, ESS, and REM% correlation analyses. N1, N2, N3, and REM were tested by analysis of variance accompanied by Bonferroni post hoc tests, and Spearman correlation tests were used to examine associations among arousal index, FQ, ESS, and REM. Statistical significance is defined as p < 0.05.

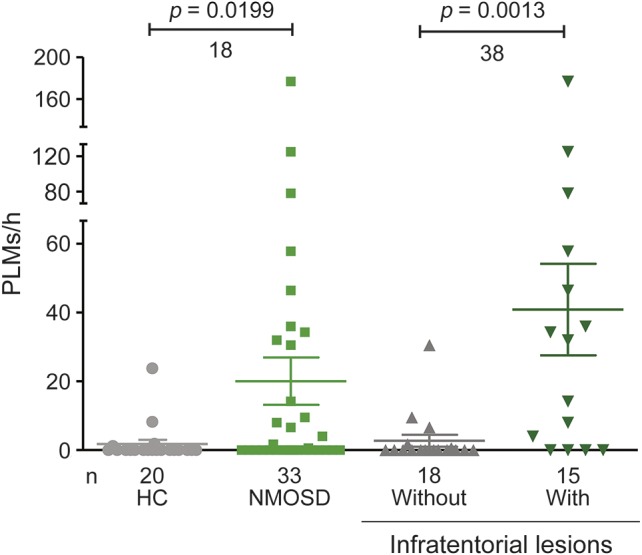

Prevalence of PLM in patients with NMOSD.

The number of PLMs/h for patients with NMOSD (mean 20, median 0, interquartile range 0–31, range 0–177) was higher than that of their healthy counterparts (mean 2, median 0, interquartile range 0–0, range 0–24) (p = 0.0199, Mann-Whitney test). Evaluated by sleep PSG, a value of PLMs/h >5 was used to diagnose PLM. Using that criterion, an increase in PLMs was found in 13 of 33 patients with NMOSD compared with 2 of 20 healthy controls (39% vs 10%, p = 0.0284). Patients with infratentorial lesions also had more PLMs/h than those without such lesions (41 vs 3, p = 0.0013, Mann-Whitney test) (figure 3). Ten of 15 NMOSD patients (67%) with infratentorial lesions had PLM. Those without infratentorial lesions had PLMs/h levels and PLM percentages that were similar to those of the healthy group (3 vs 2, p = 0.61 and 17% vs 10%, p = 0.6525, respectively). No difference in PLMs/h levels and PLM percentage was found between patients with or without AQP4 antibodies. None of the 33 patients with NMOSD fulfilled diagnostic criteria11 for restless legs syndrome.

Figure 3. Comparison of periodic leg movements by groups.

Periodic leg movements per hour of sleep (PLMs/h) are shown. PLMs/h were statistically examined by Mann-Whitney test. Statistical significance is defined as p < 0.05. HC = healthy controls; NMOSD = neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder.

Sleep-disordered breathing in patients with NMOSD.

Six of 33 (18%) patients with NMOSD had an apnea-hypopnea index >5. Among them, 4 patients had mild sleep apnea, 1 had moderate sleep apnea, and 1 had severe sleep apnea (figure e-2C). All 6 of these patients had obstructive sleep apnea, and 5 of them (83%) had no infratentorial lesions. The rate of sleep-disordered breathing in the NMOSD group exceeded that in the healthy controls (18% vs 5%, p = 0.0067).

The mean Spo2 and nadir Spo2 in patients with NMOSD were lower than in controls (94% vs 96%, p = 0.0111 and 89% vs 92%, p = 0.0391, respectively). Among patients with NMOSD, 3 had mean Spo2 levels lower than 88%, but only 1 of these 3 patients had sleep apnea. No difference in mean Spo2 and nadir Spo2 was found between patients with or without infratentorial lesions and with or without AQP4 antibodies (figure e-2, A and B).

DISCUSSION

The present analysis reveals the following results: (1) the sleep architecture was disrupted in patients with NMOSD, as indicated by decreased SE, increased SL, increased WASO, decreased N3, increased REM sleep, and decreased arousal index; (2) the arousal index was notably lower in patients with NMOSD despite events that should disturb sleep, including PLMs and the expected discomfort induced by neurologic dysfunction; (3) NMOSD patients with low arousal indexes and increased REM during nocturnal sleep reported daytime sleepiness; (4) the sleep apnea experienced by patients with NMOSD was the obstructive type, but it was not more common in the group with infratentorial lesions; (5) patients with NMOSD had lower o2 saturation than controls during sleep; and (6) patients with NMOSD exhibited more PLMs than controls, and NMOSD patients with infratentorial brain lesions engaged in more PLMs than those without such lesions.

Sleep is a physiologic function of the human brain with obvious biological rhythms. Cortical neurons spontaneously generate slow oscillations in membrane potential, which appear as slow-wave activity of <4 Hz in EEGs during sleep, called slow-wave sleep.17 Aberrance of slow-wave activity, as reflected by stage N3, may signify synaptic changes in neurons.17 In addition, focal or global inflammation may induce instability of synaptic connections in the cortex.18 Decreases in the N3 stage have been reported in several neurologic diseases, such as Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis (MS), and Alzheimer disease,19,20 with documented cortical atrophy or other brain changes. Cortical alterations have been investigated in patients with NMOSD: some studies have identified gray matter volume reduction in patients with NMO,21–24 whereas 2 studies failed to confirm these findings.25,26 Moreover, both a neuropathologic study and an in vivo ultra-high-field MRI study did not detect cortical demyelination or focal cortical lesions in NMO.6,27 Nevertheless, the possibility of subtle gray matter alterations, or gray matter connections with adjacent structures, coupled with focal inflammation, may underlie the decreases in stage N3 in our patients.

According to a definition by the American Sleep Disorders Association, EEG arousal is an abrupt shift in EEG frequency, such as theta, alpha, or beta exceeding 16 Hz but not spindles, lasting between 3 and 15 seconds.28 Abnormalities in arousal frequently manifest following respiratory disturbances such as apneas and hypopneas.29 Excessive arousals likely contribute to sleep fragmentation. Nevertheless, our study provided evidence that the arousal index was decreased in patients with NMOSD despite events that could cause arousal, including PLMs and the discomfort of neurologic dysfunction. REM sleep and ESS were significantly associated with arousal index. A plausible interpretation for this finding is the possible involvement of neuronal dysfunction in the arousal- and sleep-promoting areas of the brain, for instance, the tuberomammillary nucleus of the posterior hypothalamus and brainstem nuclei that corresponded to regions of high AQP4 expression in the brain. Several case reports of symptomatic narcolepsy in NMOSD patients with periventricular third ventricle lesions concur with this explanation.30,31

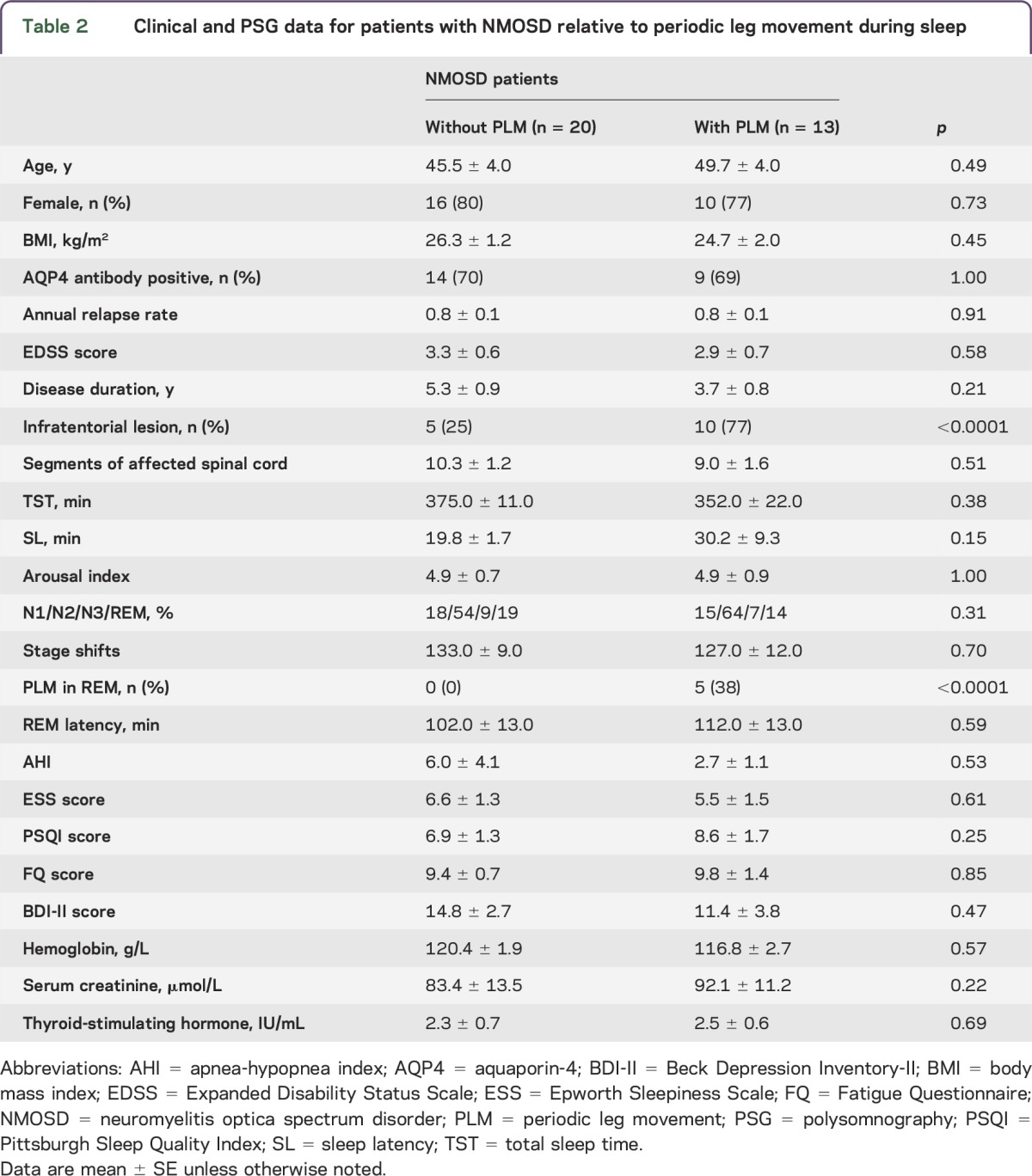

A significantly higher prevalence of PLM was found in the NMOSD group compared with the healthy controls. The neurophysiologic mechanisms and location of PLM pathology are unclear. Authors of a recent study noted that PLM can be generated in the spinal cord.32 However, a supraspinal origin was also suggested by other studies.33,34 Our data support this latter hypothesis since (1) we found that NMOSD patients with infratentorial lesions had more PLM than their lesion-free cohorts and that 10 of 13 NMOSD patients with PLM (77%) had infratentorial lesions; (2) the PLM index and PLM occurrence rate in NMOSD patients without infratentorial lesions were similar to those in the healthy group; and (3) the number of segments of injured spinal cord of NMOSD patients with PLM was similar to that of NMOSD patients without infratentorial lesions (table 2). Some have suggested that PLM causes insomnia owing to the sleep fragmentation it induces. However, others found no evidence that PLM induces arousal.35 Our data support the latter conclusion, considering our patients with PLM had similar TST and arousal indexes as patients without PLM.

Table 2.

Clinical and PSG data for patients with NMOSD relative to periodic leg movement during sleep

A study reported a predisposition for obstructive sleep apnea and accompanying central apneas among patients with MS, particularly those with brainstem involvement.36 They pointed out that regional brainstem dysfunction due to MS plaque formation might contribute to the severity of both obstructive and central sleep apnea. Patients with NMOSD, which affects the brainstem, particularly medullary reticular formation, may be at increased risk for central apneas.37,38 However, in our study, 83% of NMOSD patients with an abnormal apnea-hypopnea index did not have infratentorial lesions, and all those with sleep apnea had the peripheral obstructive type. The reason is not well-understood but might involve incomplete actions of the respiratory muscles owing to spinal injury in NMOSD-associated myelitis, which involves more severe spinal cord injuries than MS. In addition, it is notable that mean Spo2 values were significantly lower in patients with NMOSD than in controls. Chronic hypoxemias are treatable risk factors that affect patients' quality of life39; consequently, our findings underscore the importance of screening patients with NMOSD for hypoxemia in sleep and referring for PSG.

Sleep disorders and their potential contributions to fatigue in MS have gained increased attention in the past several years.40−43 Specific sleep disorders that may affect patients with MS disproportionately include PLM disorder, sleep-disordered breathing, and circadian rhythm disturbances.40−43 In our study, we found some of the abovementioned sleep problems in patients with NMOSD, but they had no significant influence on fatigue severity. The lack of association between sleep and fatigue is due in part to the complex nature of fatigue as well as the small sample size of this study, which is a limitation.

Further limitations of the study include an insufficient number of participants to allow for analysis of the relationship between sleep abnormalities and the presence of anti-AQP4 antibodies. In addition, several Chinese counterparts of English questionnaires need more rigorous validation. Nevertheless, our results will raise awareness of sleep disorders in patients with NMOSD. This recognition is expected to improve symptomatic control of a disease that requires surveillance of nocturnal symptoms, thereby improving the quality of life of patients with NMO. Although the exact neural structural abnormality leading to sleep disturbances in NMO is unknown, clarification of the structural damage and biochemical pathways underlying sleep disorders in NMOSD may shed light on disease pathogenesis and yield better symptomatic management of these patients.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the patients and the healthy volunteers for participating in this study, members of Neuroimmunology Team for various support, and Ms. P. Minick and Mr. K. Wood for editorial assistance.

GLOSSARY

- AQP4

aquaporin-4

- BDI-II

Beck Depression Inventory-II

- ESS

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- FQ

Fatigue Questionnaire

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- NMO

neuromyelitis optica

- NMOSD

NMO spectrum disorder

- PLM

periodic limb movement

- PSG

polysomnography

- PSQI

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- SE

sleep efficiency

- SL

sleep latency

- TIB

total time in bed

- TST

total sleep time

- WASO

wake after sleep onset

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org/nn

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

F.-D.S. formulated the study concept, acquired funding, and supervised execution of the study. Y.F., Y.-J. S., and F.-D.S. designed the study. L.P., Y.F., H.C., Y.-J.L., L.S., and Y. S. collected data. Y.F., L.P., and L.C. analyzed the data. Y.F., N.S., and F.-D.S. wrote the manuscript.

STUDY FUNDING

This study was supported by National Basic Research Program of China (2013CB966900), the National Science Foundation of China (81230028), National Key Clinical Specialty Construction Project of China, the US NIH (R01AI083294), and American Heart Association (14GRNT18970031).

DISCLOSURE

Y. Song, L. Pan, Y. Fu, N. Sun, Y.-J. Li, H. Cai, L. Su, Y. Shen, and L. Cui report no disclosures. F.-D. Shi has received research support from National Basic Research Program of China (2013CB966900), the National Science Foundation of China (81230028), National Key Clinical Specialty Construction Project of China, the US NIH (R01AI083294), and American Heart Association (14GRNT18970031). Go to Neurology.org/nn for full disclosure forms.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pittock SJ, Lennon VA, Krecke K, Wingerchuk DM, Lucchinetti CF, Weinshenker BG. Brain abnormalities in neuromyelitis optica. Arch Neurol 2006;63:390–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pittock SJ, Weinshenker BG, Lucchinetti CF, Wingerchuk DM, Corboy JR, Lennon VA. Neuromyelitis optica brain lesions localized at sites of high aquaporin 4 expression. Arch Neurol 2006;63:964–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin JS, Anaclet C, Sergeeva OA, Haas HL. The waking brain: an update. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:2499–2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desseilles M, Dang-Vu T, Schabus M, Sterpenich V, Maquet P, Schwartz S. Neuroimaging insights into the pathophysiology of sleep disorders. Sleep 2008;31:777–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y, Xie T, He Y, et al. Cortical thinning correlates with cognitive change in multiple sclerosis but not in neuromyelitis optica. Eur Radiol 2014;24:2334–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Popescu BF, Parisi JE, Cabrera-Gomez JA, et al. Absence of cortical demyelination in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2010;75:2103–2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarius S, Ruprecht K, Wildemann B, et al. Contrasting disease patterns in seropositive and seronegative neuromyelitis optica: a multicentre study of 175 patients. J Neuroinflammation 2012;9:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Lucchinetti CF, Pittock SJ, Wrinshenker BG. The spectrum of neuromyelitis optica. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:805–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waters PJ, McKeon A, Leite MI, et al. Serologic diagnosis of NMO: a multicenter comparison of aquaporin-4-IgG assays. Neurology 2012;78:665–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hakkinen V, Hirvonen K, Hasan J, et al. The effect of small differences in electrode position on EOG signals: application to vigilance studies. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1993;86:294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM). International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd ed Westchester, IL: AASM; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai PS, Wang SY, Wang MY, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (CPSQI) in primary insomnia and control subjects. Qual Life Res 2005;14:1943–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen NH, Johns MW, Li HY, et al. Validation of a Chinese version of the Epworth sleepiness scale. Qual Life Res 2002;11:817–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang XD, Wang XL, Ma H. Rating Scales for Mental Health. Beijing: Chinese Mental Health Journal Press; 1999:375–378. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu CY, Zheng ZH, Zhang ZL. The individual characters on nurses' occupational stress and fatigue. Chin J Nurs 2006;41:530–532. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi FD, Jia JP. Neurology and neurologic practice in China. Neurology 2011;77:1986–1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huber R, Ghilardi MF, Massimini M, Tononi G. Local sleep and learning. Nature 2004;430:78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang G, Parkhurst CN, Hayes S, Gan WB. Peripheral elevation of TNF-alpha leads to early synaptic abnormalities in the mouse somatosensory cortex in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:10306–10311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singletary KG, Naidoo N. Disease and degeneration of aging neural systems that integrate sleep drive and circadian oscillations. Front Neurol 2011;2:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trojan DA, Kaminska M, Bar-Or A, et al. Polysomnographic measures of disturbed sleep are associated with reduced quality of life in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2012;316:158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duan Y, Liu Y, Liang P, et al. Comparison of grey matter atrophy between patients with neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis: a voxel-based morphometry study. Eur J Radiol 2012;81:e110–e114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chanson JB, Lamy J, Rousseau F, et al. White matter volume is decreased in the brain of patients with neuromyelitis optica. Eur J Neurol 2013;20:361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Glehn F, Jarius S, Cavalcanti Lira RP, et al. Structural brain abnormalities are related to retinal nerve fiber layer thinning and disease duration in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Mult Scler Epub 2014 Jan 29. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Sanchez-Catasus CA, Cabrera-Gomez J, Almaguer Melian W, et al. Brain tissue volumes and perfusion change with the number of optic neuritis attacks in relapsing neuromyelitis optica: a voxel-based correlation study. PLoS One 2013;8:e66271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blanc F, Noblet V, Jung B, et al. White matter atrophy and cognitive dysfunctions in neuromyelitis optica. PLoS One 2012;7:e33878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calabrese M, Oh MS, Favaretto A, et al. No MRI evidence of cortical lesions in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2012;79:1671–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinnecker T, Dörr J, Pfueller CF, et al. Distinct lesion morphology at 7-T MRI differentiates neuromyelitis optica from multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2012;79:708–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.EEG arousals: scoring rules and examples: a preliminary report from the Sleep Disorders Atlas Task Force of the American Sleep Disorders Association. Sleep 1992;15:173–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramanand P, Bruce MC, Bruce EN. Transient decoupling of cortical EEGs following arousals during NREM sleep in middle-aged and elderly women. Int J Psychophysiol 2010;77:71–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baba T, Nakashima I, Kanbayashi T, et al. Narcolepsy as an initial manifestation of neuromyelitis optica with anti-aquaporin-4 antibody. J Neurol 2009;256:287–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanbayashi T, Shimohata T, Nakashima I, et al. Symptomatic narcolepsy in patients with neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis: new neurochemical and immunological implications. Arch Neurol 2009;66:1563–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Telles SC, Alves RS, Chadi G. Spinal cord injury as a trigger to develop periodic leg movements during sleep: an evolutionary perspective. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2012;70:880–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cruccu G, Iannetti GD, Marx JJ, et al. Brainstem reflex circuits revisited. Brain 2005;128:386–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wechsler LR, Stakes JW, Shahani BT, Busis NA. Periodic leg movements of sleep (nocturnal myoclonus): an electrophysiological study. Ann Neurol 1986;19:168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sasai T, Inoue Y, Matsuura M. Clinical significance of periodic leg movements during sleep in rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. J Neurol 2011;258:1971–1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braley TJ, Segal BM, Chervin RD. Sleep-disordered breathing in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2012;79:929–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kister I, Ge Y, Herbert J, Sinnecker T, Wuerfel J, Paul F. Distinction of seropositive NMO spectrum disorder and MS brain lesion distribution. Neurology 2013;81:1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matthews L, Marasco R, Jenkinson M, et al. Distinction of seropositive NMO spectrum disorder and MS brain lesion distribution. Neurology 2013;80:1330–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharpe AL, Calderon AS, Andrade MA, Cunningham JT, Mifflin SW, Toney GM. Chronic intermittent hypoxia increases sympathetic control of blood pressure: role of neuronal activity in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2013;305:H1772–H1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cote I, Trojan DA, Kaminska M, et al. Impact of sleep disorder treatment on fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2013;19:480–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaminska M, Kimoff RJ, Benedetti A, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2012;18:1159–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veauthier C, Radbruch H, Gaede G, et al. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis is closely related to sleep disorders: a polysomnographic cross-sectional study. Mult Scler 2011;17:613–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Veauthier C, Paul F. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: which patient should be referred to a sleep specialist? Mult Scler 2012;18:248–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.