Abstract

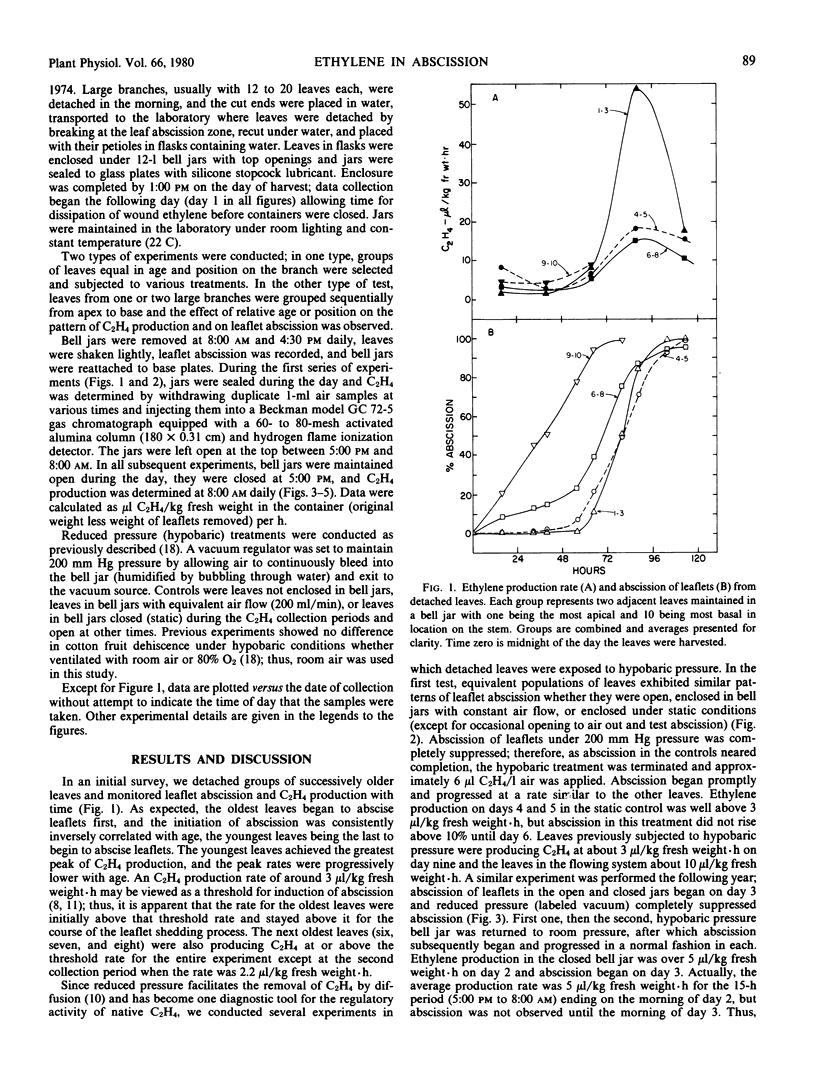

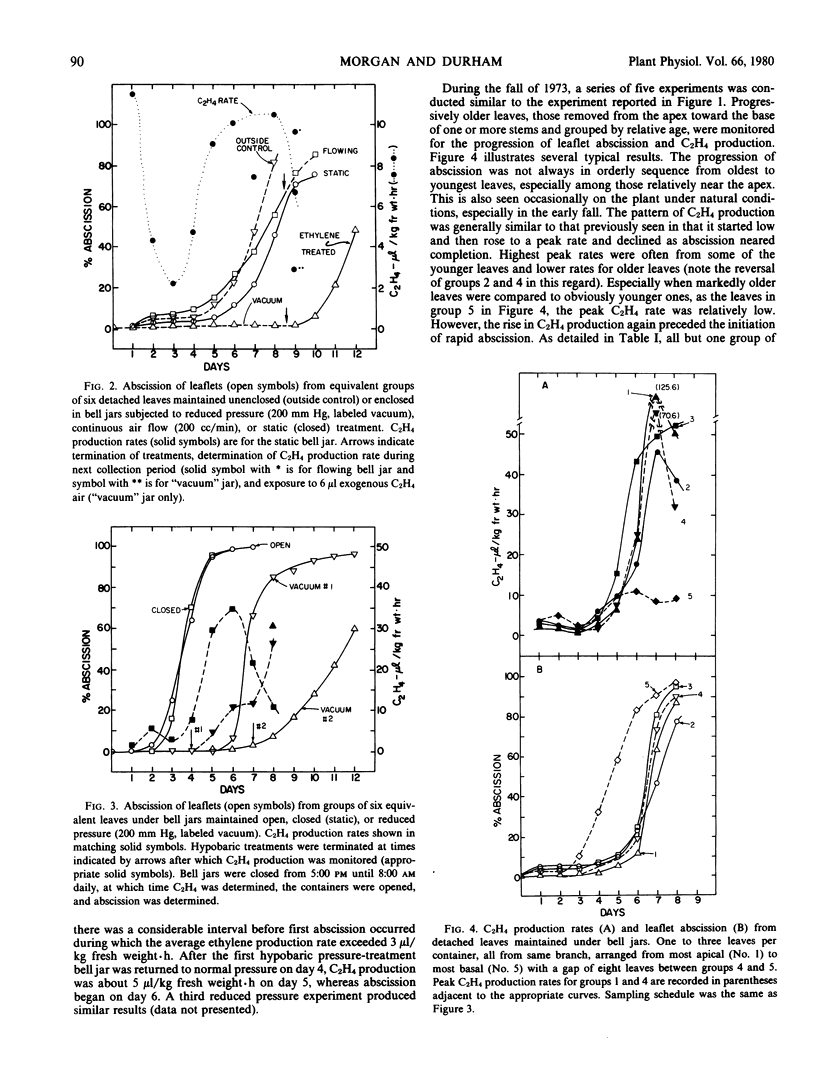

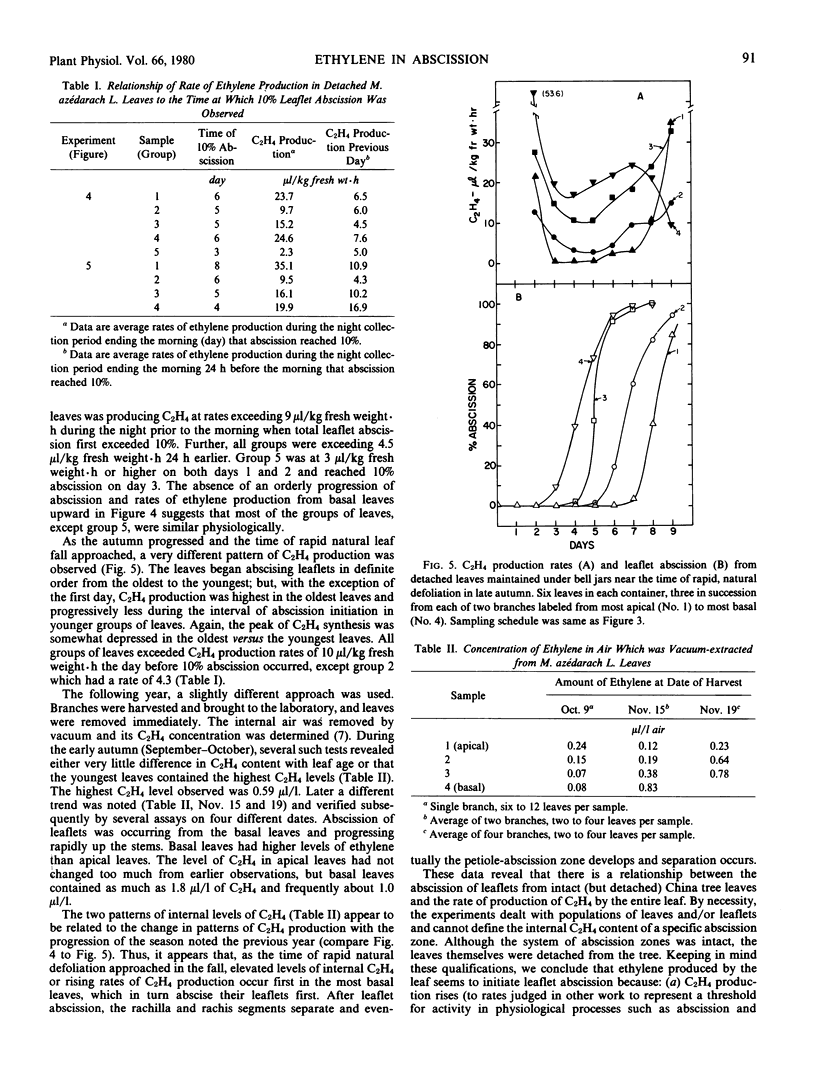

Ethylene production or content was compared to leaflet abscission in detached, compound leaves of Mèlia azédarach L. In late autumn, when abscission was progressing from basal leaves upward, the oldest leaves both produced ethylene at the highest rates and abscised their leaflets first. When C2H4 levels were measured in intercellular air removed immediately after leaves were harvested, C2H4 levels were also highest in basal leaves and declined progressively in more apical leaves. Levels as high as 1.8 microliters C2H4 liter−1 air were observed. Earlier in the season groups of leaves demonstrated a pattern of sequential initiation of abscission from base to apex, but the peak rates of C2H4 production followed an opposite trend, being highest in the youngest leaves. Peak rates of C2H4 production occurred after the initiation of leaflet abscission and presumably are related to either the auxin content or a climacteric-like, autocatalytic phase of C2H4 production not directly involved in the initiation of abscission. In these experiments, the early abscission of the older leaflets reflects their greater sensitivity to C2H4, presumably due to lower auxin content. C2H4 production rates in all experiments, with rare exceptions, exceeded 3 microliters per kilogram fresh weight per hour at least 24 hours before leaflet abscission reached 10%. This achieving of a threshold internal C2H4 level is viewed as an initiating event in leaflet abscission. Hypobaric conditions, to facilitate the escape of endogenous C2H4, delayed abscission compared to controls, and termination of hypobaric exposure allowed a normal progression of abscission as well as normal C2H4 synthesis rates. All of the data indicate that C2H4 initiates leaflet abscission in intact but detached leaves of Mèlia azédarach L. The seasonal patterns observed suggest that C2H4, in concert with those hormones which govern sensitivity to C2H4, regulate autumn leaf fall in this species.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aharoni N., Anderson J. D., Lieberman M. Production and action of ethylene in senescing leaf discs: effect of indoleacetic Acid, kinetin, silver ion, and carbon dioxide. Plant Physiol. 1979 Nov;64(5):805–809. doi: 10.1104/pp.64.5.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharoni N., Lieberman M. Ethylene as a regulator of senescence in tobacco leaf discs. Plant Physiol. 1979 Nov;64(5):801–804. doi: 10.1104/pp.64.5.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharoni N., Lieberman M. Patterns of ehtylene production in senescing leaves. Plant Physiol. 1979 Nov;64(5):796–800. doi: 10.1104/pp.64.5.796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yehoshua S., Aloni B. Effect of Water Stress on Ethylene Production by Detached Leaves of Valencia Orange (Citrus sinensis Osbeck). Plant Physiol. 1974 Jun;53(6):863–865. doi: 10.1104/pp.53.6.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer E. M., Morgan P. W. A method for determining the concentration of ethylene in the gas phase of vegetative plant tissues. Plant Physiol. 1970 Aug;46(2):352–354. doi: 10.1104/pp.46.2.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer E. M., Morgan P. W. Abscission: the role of ethylene modification of auxin transport. Plant Physiol. 1971 Aug;48(2):208–212. doi: 10.1104/pp.48.2.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg S. P., Burg E. A. Fruit storage at subatmospheric pressures. Science. 1966 Jul 15;153(3733):314–315. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3733.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg S. P. Ethylene, plant senescence and abscission. Plant Physiol. 1968 Sep;43(9 Pt B):1503–1511. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A. O., Larkins B. A. Influence of Ionic Strength, pH, and Chelation of Divalent Metals on Isolation of Polyribosomes from Tobacco Leaves. Plant Physiol. 1976 Jan;57(1):5–10. doi: 10.1104/pp.57.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M. B., Osborne D. J. Ethylene, the natural regulator of leaf abscission. Nature. 1970 Mar 14;225(5237):1019–1022. doi: 10.1038/2251019a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipe J. A., Morgan P. W. Ethylene: Response of Fruit Dehiscence to CO(2) and Reduced Pressure. Plant Physiol. 1972 Dec;50(6):765–768. doi: 10.1104/pp.50.6.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipe J. A., Morgan P. W. Ethylene: role in fruit abscission and dehiscence processes. Plant Physiol. 1972 Dec;50(6):759–764. doi: 10.1104/pp.50.6.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marynick M. C. Patterns of Ethylene and Carbon Dioxide Evolution during Cotton Explant Abscission. Plant Physiol. 1977 Mar;59(3):484–489. doi: 10.1104/pp.59.3.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMichael B. L., Jordan W. R., Powell R. D. An effect of water stress on ethylene production by intact cotton petioles. Plant Physiol. 1972 Apr;49(4):658–660. doi: 10.1104/pp.49.4.658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]