Abstract

Major depressive disorder is often linked to stress. Whereas short-term stress is without effect in mice, prolonged stress leads to depressive-like behavior, indicating that an allostatic mechanism exists in this difference. Here we demonstrate that mice after short-term (1h/day for 7days) chronic restraint stress (CRS), do not display depressive-like behavior. Analysis of the hippocampus of these mice showed increased levels of neurotrophic factor-α1(NF-α1) (also known as carboxypeptidase E, CPE), concomitant with enhanced fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) expression, and an increase in neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus. In contrast, after prolonged (6h/day for 21days) CRS, mice show decreased hippocampal NF-α1 and FGF2 levels and depressive-like responses. In NF-α1-knock out mice, hippocampal FGF2 levels and neurogenesis are reduced. These mice exhibit depressive-like behavior which is reversed by FGF2 administration. Indeed, studies in cultured hippocampal neurons reveal that NF-α1 treatment directly up-regulates FGF2 expression through ERK-Sp1 signaling. Thus, during short-term CRS, hippocampal NF-α1 expression is up-regulated and it plays a key role in preventing the onset of depressive-like behavior through enhanced FGF2-mediated neurogenesis. To evaluate the therapeutic potential of this pathway, we examined, rosiglitazone, a PPARγ agonist, which has been shown to have antidepressant activity in rodents and humans. Rosiglitazone up-regulates FGF2 expression in a NF-α1-dependent manner in hippocampal neurons. Mice fed rosiglitazone show increased hippocampal NF-α1 levels and neurogenesis compared to controls; thereby indicating the antidepressant action of this drug. Development of drugs that activate the NF-α1/FGF2/neurogenesis pathway can offer a new approach to depression therapy.

Keywords: Carboxypeptidase E, Fibroblast Growth Factor 2, depression, neurogenesis, rosiglitazone

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the most common neuropsychiatric illnesses in the US and its development has often been linked to stressful conditions 1. MDD is a complex condition with different etiologies and the molecular and cellular basis for this disorder is far from being understood. Studies have long indicated the roles of norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin in the pathogenesis of depression 2, 3. More recently neurotrophic and other growth factors, which can directly promote neurogenesis in the hippocampus, have been found to play a role in ameliorating depression 4-6. In our present study, we focused on the role of neurotrophic and growth factors in preventing stress-induced depression.

Numerous studies have linked stress as a precipitating factor for depression in humans 1 and animals 7. Interestingly, chronic restraint stress (CRS) administered over 7 or 21 days in mice enhances plasma corticosterone to similar levels in both treatment paradigms, but only the prolonged stressed mice display depressive-like behavior 8. These results indicate that an allostasis mechanism exists to prevent depression onset during the short-term CRS, despite the increase in corticosterone levels. However, such a mechanism has not been previously described.

Stress causes the release of glucocorticoids and has long been known to affect hippocampal morphology and function 9. The hippocampus contains high levels of glucocorticoid receptors, and hormones, including glucocorticoids that are secreted in response to stress. This hormone negatively influences neurogenesis and promotes apoptosis in this brain region 10. Interestingly, antidepressant drugs can reverse these effects in animal models 11. In depressed patients, imaging studies have revealed that the volume of the hippocampus, basal ganglia, and frontal lobes are smaller than those in normal subjects 12. Other investigators have reported that hippocampal gray matter is reduced in depressed patients and that it is increased after antidepressant treatment 13. Additionally, stem cell and neuroprogenitor cell proliferation in the hippocampus have been shown to be influenced by antidepressant drugs 14, 15. These studies all suggest that depression is linked to a decrease in hippocampal cell proliferation and neurogenesis. Moreover, monoamine/serotonin-based antidepressants can reverse these processes, demonstrating that these neurotransmitter systems are involved 11, 14.

Stress-induced secretion of glucocorticoids has been shown to decrease serotonin levels as well as neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus. Whether serotonin is directly responsible for the attenuation of neurogenesis remains controversial (for review see 16). Serotonin may act through different pathways to possibly stimulate secretion of neurotrophic factors such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which then enhances neurogenesis. Indeed, numerous studies have suggested that neurotrophins play a role in MDD (for review, see 4). Furthermore, work in animal models has demonstrated that stress can reduce the levels of BDNF, which may negatively influence hippocampal neurogenesis, leading to depressive-like responses 7. In addition, treatment with antidepressants increases BDNF levels in depressed patients 17. However, other studies including reports that conditional forebrain knock-out of BDNF or its receptor in mice do not result in depressive-like behaviors suggesting that BDNF, while being involved in mediating antidepressive activity, may not be a key modifier of these responses 5.

Another growth factor, Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 (FGF2), has also been correlated with MDD 18. FGF2 is down-regulated in MDD postmortem frontal cortex compared with normal controls 6. In rats, repeated social defeat stress reduces the expression of FGF2 in the hippocampus and it precipitates depressive-like behavior which can be rescued by intracerebral administration of FGF2 19. In the chronic unpredictable stress (CUS) model, peripheral administration of FGF2 restores FGF receptor 1 expression in the hippocampus and it ameliorates depressive-like behavior 20. Similarly, local infusion of FGF2 into the frontal cortex of CUS mice normalizes depressive-like behaviors and restores oligodendrocyte proliferation. Additionally, FGF2 treatment has been reported to increase neurogenesis, survival and proliferation of neurons and astrocytes in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus 18. Collectively, these studies indicate that FGF2 possesses endogenous antidepressant activity and that it can modulate neurogenesis in the hippocampus, and glial proliferation in the frontal cortex 6.

Recently, Neurotrophic Factor-α1 (NF-α1) 21, first known as carboxypeptidase E (CPE), a prohormone processing enzyme 22, 23; has been shown to be involved in depressive-like behavior in Cpefat/fat mice, which carry a point mutation in the Cpe gene 24. However, the mechanism of action of NF-α1 in antidepression is unknown. NF-α1/CPE is highly expressed in the CA1-3 regions of the hippocampus where it can play a neuroprotective role in vivo in mice under stress 25, 26. Ex vivo studies have shown that it promotes hippocampal neuronal cell survival, independent of its protease activity 21.

In this study, we have investigated the role of NF-α1 in the hippocampus in preventing the onset of depressive-like behavior in mice after short-term chronic stress to maintain allostasis. We analyzed the expression of NF-α1 and its effect on FGF2 biosynthesis, as well as on neurogenesis in the hippocampus of mice subjected to short- term CRS (1 h/d for 7 days) which does not result in depressive-like behavior, and after prolonged CRS (6h/d for 21 days), which does result in depressive-like behavior, as reported in the literature 8. Furthermore, we examined the effect of genetic deletion of NF-α1/CPE on depressive-like behavior, hippocampal FGF2 expression and neurogenesis. Our study identified NF-α1 as a key modifier during short-term CRS that enhanced FGF2 expression and neurogenesis in the hippocampus to prevent the onset of depressive-like behavior and maintain allostasis. Additionally, since current treatment strategies for MDD use primarily monoamine-based antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or serotonin-, norepinephrine-, and dopamine- enhancing drugs, which are not always effective 27, we explored the possibility that a drug that might activate this hippocampal NF-α1/FGF2/neurogenesis pathway could offer an alternative treatment approach. To this end we found that the anti-diabetic drug, rosiglitazone that has been reported to possess antidepressant activity in rodents and humans 28, 29 activated this pathway.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Taconic (Hudson, NY), Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) or a colony maintained by the NIA under contractual agreement with Harlan Sprague Dawley, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN). NF-α1/CPE knock-out (KO) mice and their wild type (WT) and heterozygous (HET) littermates were raised in the NIH animal facility. All animals were given food and water ad libitum in a humidity and temperature controlled room on a 12 h (NIH, University of Toledo) or 14:10 h (Duke) light:dark cycle. Animal procedures were approved by the respective Animal Care and Use Committees of NICHD, NIH, Duke University, and University of Toledo.

Restraint stress paradigm

All mice (10-12 wk old) were individually housed during the course of the study (restraint and controls). Restraint was from 0900-1000 h (short-term) or 0900-1500 h each day (long-term). The short-term chronic restraint stress paradigm 1 h/day for 7 days was performed exactly as described previously 30. These durations of restraint were considered sufficient based on reported increases in plasma corticosterone levels after short-term (1 h/d) restrained compared to non-restrained mice 31. Therefore, in the short-term stress condition, it was more humane not to subject mice to a higher intensity of stress e.g. 6h/day for 7 days which also does not produce depressive-like behavior, but the mice exhibit chronic stress parameters 8. For long-term chronic stress, we used a paradigm of restraint for 6h/day exactly as described for 21 days that has been reported to produce depressive-like responses 8.

Sucrose preference test

The test was conducted in the home cage where mice were housed individually for 7 days before and throughout the study as described in Willner et al. 32 with modifications. Prior to beginning the testing, mice were habituated to the presence of two calibrated drinking bottles containing sterile water for 5 days. Following this acclimation, mice had the free choice of either drinking the 1% sucrose solution or sterile water for a period of 4 days. The volume of water and sucrose solution intake was measured daily, and the positions of two bottles were switched daily to reduce any confounding issues produced by side bias. Sucrose preference was calculated as a percentage of the volume of sucrose intake over the total volume of fluid intake and averaged over the 4 days of testing.

Forced swim test

This procedure was conducted at Duke University (C57BL/6 WT and CPE/NF-α1 KO mice) and at the NIH animal facility (WT and CPE/NF-α1 HET mice). After restraint stress, testing was done ∼ 18 h following the end of restraint. Immediately after testing, brain tissues were removed and stored at -80°C until processed. For the FGF2 rescue experiments, mice (9-10 week old) were treated for 30 consecutive days with vehicle (PBS) or 5 ng/g (s.c.) 17 kD recombinant FGF2 (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN). On the day of testing, mice received their daily injection of vehicle or FGF2 30 min before the test. The forced swim test was conducted at 1300-1600 h with modification in the scoring time as described in Fukui and colleagues 33. Videos from forced swim tests were scored with automated behavioral recognition systems and time spent immobile was validated for each automated scoring method using the Noldus Observer XT (Noldus Information Technologies, Leesburg, VA). For WT and NF-α1-KO mice given daily administration of FGF, time immobile was scored using Cleversys Forced Swim Scan (Cleversys Inc., Reston, VA). For restraint studies, time spent immobile was scored with Noldus Ethovision 10 (Noldus Information Technologies, Leesburg, VA). For the HET mice tested at NIH, immobility was recorded manually over the last 4 min of the 6 min test.

Treatment of mice with Rosi

These experiments were conducted at the University of Toledo animal facility. Four animals (20 wk. old) were fed 5 grams of food per day per animal with pelleted chow (F05072, Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ) supplemented with rosiglitazone maleate (Avandia, GlaxoSmithKline, King of Prussia, PA) at a concentration of 0.14 mg/g of chow. The control group was fed the same amount of non-supplemented chow. Animals were fed for 21 days. The dose of Rosi calculated at the end of experiment was 20 mg/kg body weight/day. The mice were euthanized and the brains removed, rapidly frozen, and stored at -80°C for future analysis.

Preparation of hippocampal neurons and treatment with NF-α1 and other agents

Hippocampal neuronal cultures were prepared as described previously 21. The neurons were treated with recombinant NF-α1/CPE (0.4 μM) 21 and various reagents: 2 μM GEMSA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 5 μM ERK inhibitor (U0126), 10 μM Akt inhibitor (LY294002) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), 0.5 μM Mithramycin A (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 1 μM rosiglitazone (Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI), 30 nM NF-α1 siRNA or scrambled siRNA oligos (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or vehicle, for various times (see text and legend) and then harvested for protein or RNA extraction. In secretion experiments, media from 1×106 hippocampal neurons grown in 1 ml of culture medium was collected, centrifuged for 15 min at 12000 g to remove cell debris and the supernatant analyzed by Western blot.

Assay of mRNA expression by quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from hippocampus or primary cultures of hippocampal neurons and prepared for qRT-PCR as described 21, using 100 nM (18S rRNA) or 300 nM (FGF, DCX) primers. The cycling conditions were: 10 min denaturation at 95°C and 40 cycles of DNA synthesis at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Primer sequences for FGF1 fwd: 5′- cagaggacgctggataggag-3′, rev: 5′- tccactgtcacatccctcaa-3′; for FGF2 fwd: 5′- cacttaccggtcacggaaat-3′, rev: 5′- ccgttttggatccgagttta-3′; for Doublecortin (DCX): fwd: 5′-ggccaaactggtgtgagatt-3′, rev: 5′-ccccaggtatgccagataga-3′; for 18S-fwd: 5′-CTCTTAGCTGAGTGTCCCGC-3′, rev: 5′-CTGATCGTCTTCGAACCTCC-3′.

Western blot

Protein lysates of whole hippocampal tissue or neurons in culture were prepared by homogenizing the tissue or primary cultured hippocampal neurons in T-protein extraction reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) supplemented with 1× Complete Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche,) and centrifuged. Lysates and secretion media collected from cultured hippocampal neurons were analyzed by Western blot exactly as described previously 30. 30 μg of protein (from lysates) or 20 μl of medium suspended in 30 μl of SDS gel sample buffer were denatured at 70°C for 10 min and run on 4-12% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), according to the standard protocol. After blocking with 5% nonfat milk at room temperature for 1 h, the membrane was incubated with primary antibodies overnight. After washing, the membrane was incubated with fluorescent conjugated anti-mouse or rabbit antibodies, visualized by the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR, Inc), and the bands were quantified by the Odyssey software, version 2.1. The protein expression level for each sample (for lysates) was normalized to β-actin. Monoclonal mouse anti-CPE antibody was from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Polyclonal rabbit anti-FGF2 antibody (directed against the C-terminus aa188-210, 1:3,000) was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Monoclonal mouse anti-β-actin antibody (1:10,000) was from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA).

Immunohistochemistry

For FGF2 immunostaining, brain sections were prepared as described 34. The brains of 12 NF-α1-KO mice and 12 WT littermates at 6-, 14-, and 30-wk of age (2 male and 2 female mice of each genotype, sex, and age) were dissected from perfused mice and embedded (24 mouse brains per block) in a gelatin matrix using MultiBrain™ Technology (NeuroScience Associates, Knoxville, TN). The MultiBrain™ block was sectioned in the coronal plane at 35 μm on an AO 860 sliding microtome. Every 8th free-floating section was used for FGF2 immunohistochemistry and was stained as described 34, using a rabbit anti-FGF2 antibody (1:1,500 dilution, LifeSpan Biosciences). For DCX staining, 35 μm brain sections from perfused FGF2 treated or naïve WT and CPE-KO mice were cut under contract by NeuroScience Associates. The sections were then stained for DCX using polyclonal rabbit anti-doublecortin (1:2,000, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) followed by Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Every 10th free-floating section was used for DCX immunostaining.

Quantification of FGF2 and DCX immunoreactivity

For FGF2 quantification, images covering the whole hippocampal area were captured by a Nikon fluorescent microscope (eclipse 80i) with a mounted digital camera and analyzed using Image J software. Low magnification (4×) images were used to quantify the FGF2 by tracing the area of staining, while the high magnification (20×) images were used for mean pixel intensity quantification using three equal randomly chosen squared areas (100 × 100 pixel or 31.4 × 31.4 μm) and averaged. For DCX immunopositive cell counting, images covering the dentate gyrus were captured by a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510 Inverted Meta) with 20× magnification. DCX positive cells in the subgranular zone (SGZ) were counted in sections through the whole hippocampal formation of each mouse and averaged. Four mice were analyzed for each group.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as means and standard errors (SEM). Biochemical data were analyzed where noted by Student's t-test and by one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey or Bonferroni's post-hoc multiple comparisons tests. For immunocytochemistry data, student's t-test or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc multiple comparison tests were used. The behavioral data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, SPSS 21 (IBM North America, New York, NY). Post-hoc comparisons were by Bonferroni's corrected pair-wise comparisons; in all cases, a p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Short-term chronic restraint stress up-regulates NF-α1, FGF2, and doublecortin expression in the hippocampus

Mice were subjected either to the short-term (1 h/d for 7 days) or long term chronic restraint stress (CRS) (6 h/d for 21 days) and then assessed for depressive-like behavior ∼18 h later using the forced swim test. A two-way ANOVA found the treatment [F(1,39)=34.880, p<0,001] and the restraint condition by time interaction to be significant [F(1,39)=15.519, p<0.001] (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Bonferroni corrected pair-wise comparisons observed that while immobility times in the short-term restraint-stressed mice were not significantly different from that of the 7d non-stressed animals, long-term restraint-stress augmented immobility time relative to the 21-day non-stressed control (p<0.001).

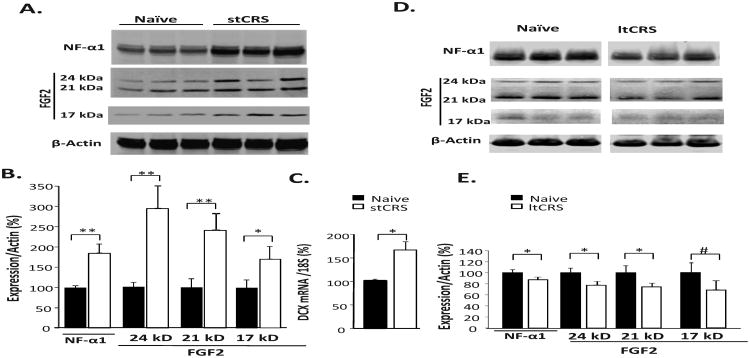

After the short-term CRS, the hippocampi of the mice were analyzed by Western blot. Figure 1A shows the protein levels of NF-α1 and FGF2 in the CRS-treated and naïve mice. Quantification of the bands (Fig. 1B) reveals that NF-α1 and three forms of FGF2 (24 kD, 21 kD and 17 kD isoforms) were significantly increased in the stressed compared to the naïve mice (NF-α1: p<0.01; 24 kD FGF2: p<0.01; 21 kD FGF2: p<0.01; 17 kD FGF2: p<0.05). Analysis of doublecortin (DCX) mRNA in the hippocampus, as a quantitative indicator of immature neurons in the subgranular zone (SGZ), showed a significant increase (p<0.05) in the stressed mice compared to the naïve mice (Fig. 1C). In the cortex, which did not show an increase in NF-α1 expression after short-term CRS, there was no increase in FGF2 expression in any of the isoforms (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Figure 1. Short-term restraint stress stimulates FGF2 and DCX expression in mouse hippocampus.

(A) Western blot analysis and (B) quantification show significant increases in NF-α1 protein and 17 kD, 21 kD and 24 kD isoforms of fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) in the hippocampus dissected from mice ∼18 h after short-term chronic restraint-stress (stCRS) compared to naïve controls, for each protein. (C) Expression of doublecortin (DCX) mRNA in the hippocampus was also increased in mice after stCRS compared to the naïve group indicative of neurogenesis after short term CRS. (D) Western blot analysis and (E) quantification show a significant decrease in NF-α1 protein and 17 kD, 21 kD and 24 kD FGF2 in the hippocampus dissected from mice ∼18 h after long-term chronic restraint-stress (ltCRS) compared to naïve controls. (B, C), n = 6/group; (D, E), n=5/group; the values are the mean ± SEM, *p<0.05, **p<0.01. Note: # indicates statistical significance reached here upon exclusion of one outlying point (i.e., n=4).

In contrast, after long-term CRS (6 h/d for 21 days) mice showed more immobility in the forced swim test compared to control animals (Supplementary Fig. S1A), indicative of depressive-like behavior. Western blot analysis and quantification (Fig. 1D, E) revealed a significant decrease in NF-α1 protein (p<0.05) and 21 kD (p<0.05) and 24 kD FGF2 (p<0.05) in the hippocampus of these mice relative to naïve controls. The 17 kD FGF2 also showed a decrease after long-term CRS, although not statistically significant due to one outlier point that was >2 SD from the mean, which when excluded yielded significance (p<0.05; n = 4) (Fig. 1E). These Western blot results demonstrate a co-ordinate regulation between NF-α1 and FGF2 in the hippocampus and this correlates with the depressive-like phenotype in mice after restraint-stress.

Genetic ablation of NF-α1 in mice leads to depletion of FGF2 in hippocampus and depressive-like behavior

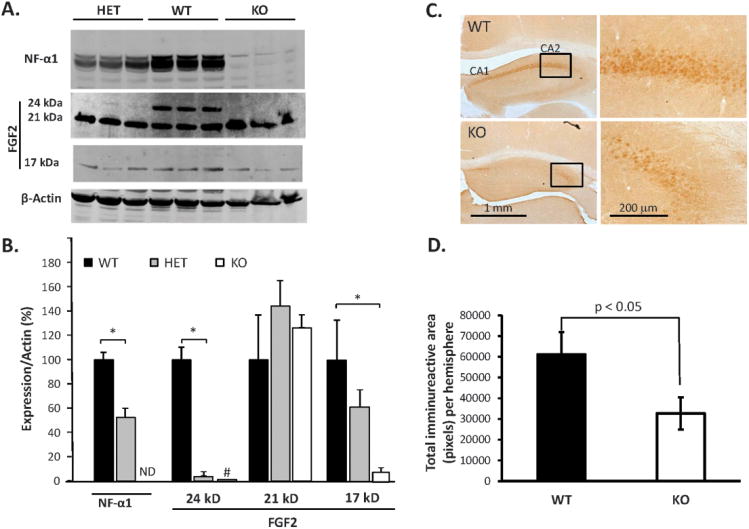

To investigate the link between NF-α1 and FGF2 protein expression and in vivo depressive-like behavior, the genetically ablated NF-α1-knockout (previously known as CPE-KO) mouse model was studied 35. NF-α1 and FGF2 proteins were analyzed in the hippocampus of wild-type (WT), heterozygous (NF-α1-HET) and homozygous mutant (NF-α1-KO) mice 35. As expected, the levels of NF-α1 were undetectable in the NF-α1-KO animals while the HET mice showed reduced levels compared to WT mice (t-test p<0.05) (Fig. 2A, top and B). Analysis of FGF2 revealed that the 24 kD isoform was greatly reduced in the hippocampus of HET and barely detectable or undetectable in NF-α1-KO mice compared to WT mice (t-test p<0.05 WT vs. HET) (Fig. 2A, middle and B). The 17 kD isoform [one-way ANOVA F(2,15)=13.66, p<0.05] was also greatly decreased in NF-α1-KO mice relative to WT controls (Bonferroni post-hoc test, p<0.05), while it was decreased also in HET mice, it did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2A and B). In contrast, the levels of the 21 kD FGF2 isoform were not distinguished by genotype (Fig. 2A and B). Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of FGF2 in 6-wk old WT and NF-α1-KO hippocampus showed that immunoreactive (IR) staining localized primarily to 3 areas: the fasciolarum cinereum (supplementary Fig.S3), and the CA1 and CA2 hippocampus (Fig. 2C), which were semi-quantitatively analyzed for FGF2 immunostaining in 6-, 14-, and 30-wk old mice (supplementary Table S1). There was no detectable difference in FGF2 expression between males and females for either genotype (supplementary Table S1); however, the distribution and the intensity of the FGF2 IR were lower in the NF-α1-KO compared to WT mice in each age group. Detailed imaging analysis of 6-wk old mice showed that the total FGF2 IR in the hippocampus of NF-α1-KO mice was reduced by 50 % (p<0.05, Fig. 2D). Imaging analysis of 30-wk old mice (supplementary Fig.S4) revealed reduction in FGF2 IR in 2 KO mice compared to WT mice, while the other 2 out of the 4 NF-α1-KO mice studied at this age showed no detectable levels of FGF2 (supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2. FGF2 expression is decreased in hippocampus of NF-α1-KO mice.

(A) Western blots and (B) quantification show expression of NF-α1 and FGF2 protein in the hippocampus of wild type (WT), heterozygous (HET) and NF-α1-knock out (KO) mice. There was a significant decrease in NF-α1 and FGF2 (24 kD) and no significant difference in FGF2 (17 kD isoform) in HETs versus WT mice. NF-α1-KO mice showed a complete absence (ND = not detectable) of NF-α1 while the 24kD FGF2 was barely detectable; the 17 kD FGF2 was decreased, but 21 kD FGF2 was still present (B). n = 6/group; the values are the mean ± SEM, [one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni corrections for 21kD and 17kD FGF2 groups and t test for NF-α1 and 24kD FGF2 groups since these proteins were undetectable, or cannot be reliably quantified (denoted by #), respectively, in KO mice]. *p <0.05. (C) Immunohistochemistry showing FGF2 protein expression in the hippocampal CA1 and CA2 regions of NF-α1-KO compared to WT mice at 6 wk of age. The right image shows the magnified area of the hippocampus which is delineated in the left image. (D) Quantification of the total area of FGF2 immunoreactivity on 8 sections through the whole hippocampal formation in one hemisphere in 6-wk old WT and NF-α1-KO mice. N= 4/group; values show mean ±SEM, *p<0.05, NF-α1-KO compared to WT.

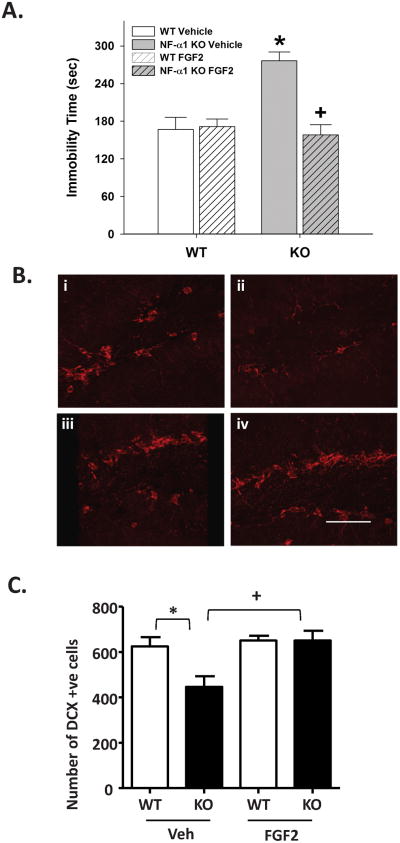

We then assessed the depressive-like behavior of NF-α1-KO mice using the sucrose preference test 32. NF-α1-KO mice had a significantly decreased preference for sucrose compared to WT mice (WT, 82.7 ± 1.3% sucrose preference, n=8; KO, 77.3±2.9% sucrose preference, n=6, t-test p<0.05), indicating that the KO mice were experiencing anhedonia. To further confirm depressive-like responses in NF-α1-KO mice, and ascertain whether FGF2 treatment could rescue this behavior, animals were administered vehicle or 5 ng/g FGF2 (s.c.) for 30 consecutive days and were tested in the forced swim test at the end of this time. A two-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of genotype [F(1, 30)=9.135, p<0.005] and treatment [F(1, 30)=9.221, p<0.005], and a significant genotype by treatment interaction [F(1, 30)=17.557, p<0.001] (Fig. 3A). Bonferroni corrected pair-wise comparisons found that between the vehicle-treated mice, NF-α1-KO mice had higher levels of immobility than the WT littermates (p< 0.001). Importantly, while FGF2 treatment did not affect WT performance, it significantly reduced immobility time in the NF-α1-KO mice relative to their vehicle controls (p< 0.001) and this level of immobility was not different from those of the WT vehicle or WT FGF2 controls. To demonstrate that the effects of FGF2 were specific for depressive-like behaviors and were not due to a general increase in motor activity, locomotor activity was examined in the open field. The 30 consecutive days of FGF2 treatment was found to decrease locomotion in the open field in both genotypes (supplementary Fig. S11) [two-way ANOVA: genotype F(1,33)=6.623, p<0.015; treatment-condition F(1,33)7.900, p<0.009; the interaction was not significant]. Hence, the FGF2-induced decrease in immobility- time (viz., increased struggle activity) in forced swim cannot be attributed to a reduction in general motor activity.

Figure 3. FGF2 administration rescues depressive-like behavior in NF-α1-KO mice and increases DCX positive immature neurons in the SGZ.

(A) Vehicle-treated NF-α1-KO mice spend more time in immobility in the forced swim test than the WT controls, indicating depressive-like behavior. For FGF2 treatment, there was no effect on WT responses; however, immobility times in NF-α1-KO mice were reduced to those of the WT controls. Data show mean ±SEM, n = 8-9 mice/genotype/treatment-condition. *p<0.05, WT versus NF-α1-KO responses; +p<0.05, within genotype comparison of vehicle versus FGF2-treated group. (B) (i-iv) Confocal photomicrographs of DCX immmunostained immature neurons in the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the dentate gyrus of WT (i) and NF-α1-KO (ii) mice injected with vehicle, and WT (iii) and NF-α1-KO (iv) mice injected with FGF2. Bar = 50 μm. (C) Quantification of DCX positive cells was performed on 6 sections through the whole hippocampal formation with focus on the SGZ of WT and NF-α1-KO mice with and without injection of FGF2. Values are the mean ±SEM, n = 4/group. *p<0.05 NF-α1-KO compared to WT; +p<0.05, FGF2 treated compared with untreated (Veh) NF-α1-KO mice.

Given that the NF-α1-HET mice also showed a substantial decrease of FGF2 (sum of 24kD + 17kD isoforms), compared to the WT controls (Fig. 2A,B), we subjected these animals to the forced swim test. These HET mice showed significantly more immobility than the WT littermates (supplementary Fig. S1B, p<0.05), indicative of depressive-like behavior in the HET animals.

FGF2 treatment of NF-α1-KO mice increases neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus

Since FGF2 administration rescued depressive-like behavior in NF-α1-KO mice, we investigated neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the FGF2-treated NF-α1-KO mice. We first compared the number of neuroprogenitor cells and immature neurons in the subgranular zone (SGZ) of WT versus NF-α1-KO mice, using the markers SOX2/GFAP and DCX, respectively. Analysis of SOX2 in the SGZ, a marker for neuroprogenitors, revealed no significant difference in the number of SOX2/GFAP positive cells between WT and NF-α1-KO mice (supplementary Fig. S5). For DCX analysis (Fig. 3B i-iv, 3C), a two-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of genotype [F(1, 10) =5.237, p< 0.05] and treatment [F(1, 10) =8.551, p< 0.05], and a significant genotype by treatment interaction [F(1, 10) = 5.093, p < 0.05]. Bonferroni post-hoc analyses determined that vehicle-treated NF-α1-KO mice had significantly (p<0.05) fewer DCX immunoreactive cells (immature neurons) in the SGZ compared to the vehicle-treated WT mice (Fig. 3C). However after FGF2 administration, the numbers of DCX positive cells in NF-α1-KO mice increased to a level similar to those of the WT controls; FGF2 treatment was without effect in WT mice (Fig. 3C). Analysis of DCX mRNA derived from the hippocampi showed a significant increase in DCX mRNA in the NF-α1-KO mice treated with FGF2 compared to the NF-α1-KO control mice (supplementary Fig. S6), demonstrating a high level of correspondence between DCX mRNA expression and immature neuron numbers in the SGZ in the NF-α1-KO mice. Thus, concomitant with the rescue of depressive-like behavior in NF-α1-KO mice, there was a significant increase in neurogenesis in the SGZ of the dentate gyrus of these mice. Additionally, FGF2 also promoted proliferation of cells in the SGZ as evidenced by an increase in Ki-67 immuno-positive cells after FGF2 treatment (supplementary Fig. S7).

NF-α1 up-regulates FGF2 expression in primary hippocampal neurons via the ERK-Sp1 signaling pathway

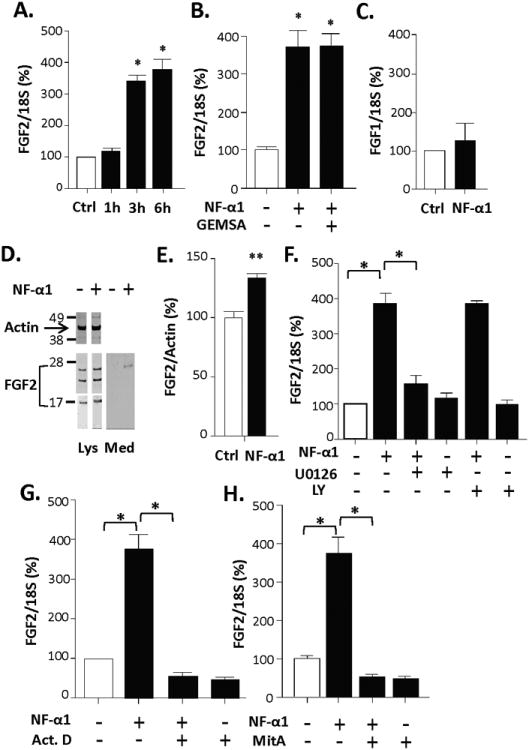

To investigate the cell biological mechanism by which NF-α1 might up-regulate FGF2 expression, we treated cultured hippocampal neurons with recombinant NF-α1/ CPE (400 nM) for 1, 3 or 6 h. A one-way ANOVA found a significant time effect [F(3, 8)=55.69, p<0.001] where this treatment resulted in a 3.5 to 4-fold increase in FGF2 mRNA at 3 (p<0.05) and 6 h (p<0.05), respectively (Fig. 4A). This increase in FGF2 mRNA occurred also in the presence of GEMSA, a specific and potent inhibitor of CPE enzymatic activity (Fig. 4B) [one-way ANOVA, treatment effect: F(2, 9)=26.97, p<0.001; p<0.05 from the vehicle-control], indicating that this action on FGF2mRNA was independent of CPE enzymatic activity. Importantly, NF-α1 treatment did not increase mRNA levels of another member of the FGF family, FGF1 (Fig. 4C). Western blot analysis of hippocampal neuronal cell lysates showed the levels of the 3 isoforms of FGF2 protein (24 kD, 21 kD, and 17 kD) were increased with NF-α1 treatment (Fig. 4D, E; t-test, p<0.01 for total FGF2 proteins), consistent with that observed in vivo. Interestingly, while the 24 kD isoform was detectable in the secretion medium after NF-α1 treatment, the 21 and 17 kD forms were not (Fig. 4D, right).

Figure 4. NF-α1 up-regulates FGF2 expression in rat cultured hippocampal neurons through ERK-Sp1 signaling.

(A) FGF2 mRNA increased in rat hippocampal neurons after NF-α1 treatment (400 nM) for 3 and 6 h. (B) Pre-incubation of the NF-α1/CPE (400 nM) with the CPE enzymatic inhibitor guanidino-ethyl-mercapto-succinic acid (GEMSA) (2 M) for 30 min did not inhibit the NF-α1-induced increase in FGF2 mRNA expression. (A, B), n = 3/group; values are mean ±SEM, *p<0.05, compared to Ctrl group. (C) Treatment with 400 nM NF-α1 for 3 h had no effect on FGF1 mRNA expression, n = 3/group; values are mean ±SEM. (D) Western blots show increased expression of 24 kD, 21 kD and 17 kD FGF2 proteins in cells (Lys) and secretion of 24 kD FGF2 (Med) after treatment of hippocampal neurons with 400 nM NF-α1 for 24 h. (E) Quantification of the Western blots from panel D shows the increase in total FGF2 protein (normalized to β-actin) with NF-α1 treatment was significant, n = 4/group; values are mean ±SEM, **p<0.01, compared to Ctrl group. (F) ERK inhibitor U0126 treatment of neurons for 3 h significantly blocked the NF-α1 (400 nM) induced FGF2 mRNA up-regulation, indicating NF-α1 signaling via the ERK pathway. Akt inhibitor LY294002 had no effect. (G) Transcription inhibitor, actinomycin D (Act.D, 1 g/ml), treatment for 3 h completely blocked NF-α1-induced up-regulation of FGF2 mRNA expression indicating that regulation is at the transcriptional level. (H) Sp1 inhibitor, mithramycin A (MitA, 0.5 M) treatment for 3 h completely blocked NF-α1-induced up-regulation of FGF2 mRNA expression, indicating that the NF-α1 response is mediated by the transcription factor Sp1 (D-F), n = 3/group; values are mean ±SEM, compared to cells treated with NF-α1 in the absence of Act.D, *p<0.05.

Based on previous results 21, we analyzed the effects of the ERK and Akt inhibitors (U0126 and LY294002, respectively) on the NF-α1-induced increase in FGF2 expression. A one-way ANOVA reported a significant effect of treatment [F(5, 12)=63.84, p<0.001). Addition of NF-α1 to the neurons for 3 h increased FGF2 mRNA by ∼4-fold (Fig. 4F; posthoc, p<0.05), consistent with that shown in Figure 4A. However, this increase was prevented by pretreatment with the ERK inhibitor, U0126 but not by the Akt inhibitor, LY294002 (ps<0.05 from the vehicle and U0126 groups) (Fig. 4F). NF-α1 induction of FGF2 expression was prevented by actinomycin D, a suppressor of DNA transcription (Fig. 4G) [one-way ANOVA, treatment effect: F(3, 8)=70.34, p<0.001; ps<0.05 from the vehicle, NF-α1-Act D, and Act D groups], indicating that this induction occurred through enhanced transcription rather than by RNA stability. Since the FGF2 promoter contains Sp1 binding sites 36, 37, we investigated whether Sp1 could mediate the NF-α1-induced up-regulation of FGF2 mRNA expression, using the Sp1 inhibitor, mithramycin A (Mit A). Figure 4H shows that the NF-α1-induced increase in FGF2 mRNA was prevented by Mit A [one-way ANOVA; treatment effect: F(3, 12)=52.23, p<0.001; ps<0.05 from the vehicle, NF-α1 -Mit A, and Mit A groups], indicating that Sp1 mediated the transcription of FGF2. Additionally, treatment of hippocampal neurons with NF-α1 promoted the transport of Sp1 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (supplementary Fig. S8; p<0.01).

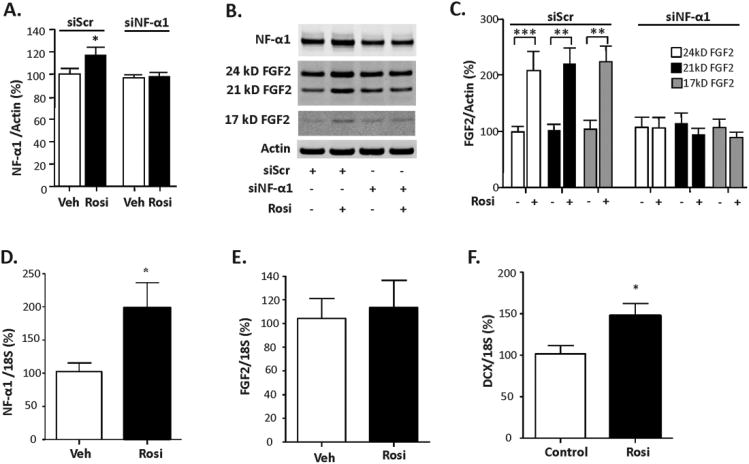

Rosiglitazone, a PPARγ agonist, up-regulates NF-α1 and FGF2 expression in hippocampal neurons and neurogenesis in mice

Our findings suggest that a pharmacological approach to stimulate the NF-α1 and FGF2 expression and the neurogenesis pathway could represent a potential new approach for treating depressive-like responses. Here we tested the effect of rosiglitazone (Rosi), a PPARγ agonist with antidepressant action 28, 29, 38, on NF-α1 and FGF2 expression and neurogenesis in hippocampal neurons and in Rosi-fed mice, respectively. The rationale for these studies was that PPARγ regulates NF-α1/CPE expression in marrow mesenchymal stem cells 39 and that bioinformatic analysis revealed several putative PPARγ response elements (PPRE) in the promoter region of mouse, rat and human NF-α1/CPE gene (supplementary Fig. S9). Figure 5A shows that in neurons transfected with scrambled siRNA (siScr), Rosi treatment up-regulated both NF-α1 (Fig. 5A, siScr, t-test p< 0.05) and FGF2 protein expression (Fig. 5B, C, 24 kD, 21 kD and 17 kD isoforms), t-test, p< 0.001, p< 0.01, p< 0.01, respectively), when compared to vehicle treated siScr cells. In contrast, cells pretreated with siNF-α1 did not show an increase in NF-α1 protein after Rosi treatment (Fig. 5A, B) and there was no concomitant up-regulation of FGF2 expression (Fig. 5B, C). This result indicates that Rosi up-regulates FGF2 expression in a NF-α1-dependent manner. In mice fed for 3 weeks a chow supplemented with Rosi, there was an increase in hippocampal NF-α1 (t-test, p<0.05) and DCX mRNAs (t-test, p<0.05), indicative of enhanced neurogenesis compared to control mice (Fig. 5D, F). FGF2 mRNA levels showed no difference between Rosi and control group after 3 weeks of Rosi administration (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5. Rosiglitazone, a PPARγ agonist, up-regulates NF-α1 and FGF2 expression in hippocampal neurons and neurogenesis in Rosi-fed mice.

(A) Quantification of NF-α1 protein levels from Western blots of hippocampal neurons transfected with scrambled siScr or siNF-α1 for 24 h and then treated with vehicle (Veh) or 1 μM rosiglitazone (Rosi) for 24 h. Rosi treatment significantly increased NF-α1 protein in siScr but not siNF-α1 transfected neurons, n = 10/group; values are mean ±SEM, *p<0.05, Rosi compared to Veh in siScr group. (B) Western blots and (C) quantification show increased protein levels of the 24 kD, 21 kD and 17 kD FGF2 isoforms in siScr transfected neurons treated with Rosi. In neurons treated with siNF-α1, Rosi failed to increase FGF2 isoforms indicating NF-α1-dependence. n = 10/group; values are mean ±SEM, ***p<0.001 Rosi compared to Veh in the siScr group for 24 kD, 21 kD and 17 kD FGF2; **p<0.01 Rosi compared to Veh in the siScr group for 21 kD FGF2. (D, E, F) Hippocampal NF-α1, FGF2 and DCX mRNA levels of Rosi-fed mice. Hippocampal NF-α1 and DCX mRNA levels were significantly increased in mice fed rosiglitazone (Rosi) for 21 days. n = 4/group; *p<0.05.

Discussion

Prolonged chronic stress leads to MDD in humans and depressive-like behavior in animal models 8. This is accompanied by changes such as apical dendrite retraction and neurodegeneration in the hippocampus 40. However, with short-term chronic stress of 7 days there is resistance to the onset of depressive-like behavior, despite this fact, levels of corticosterone are elevated to the same extent as in prolonged stress in mice 8. How the brain develops protection against chronic stress-induced depressive-like behavior to maintain allostasis is not fully known.

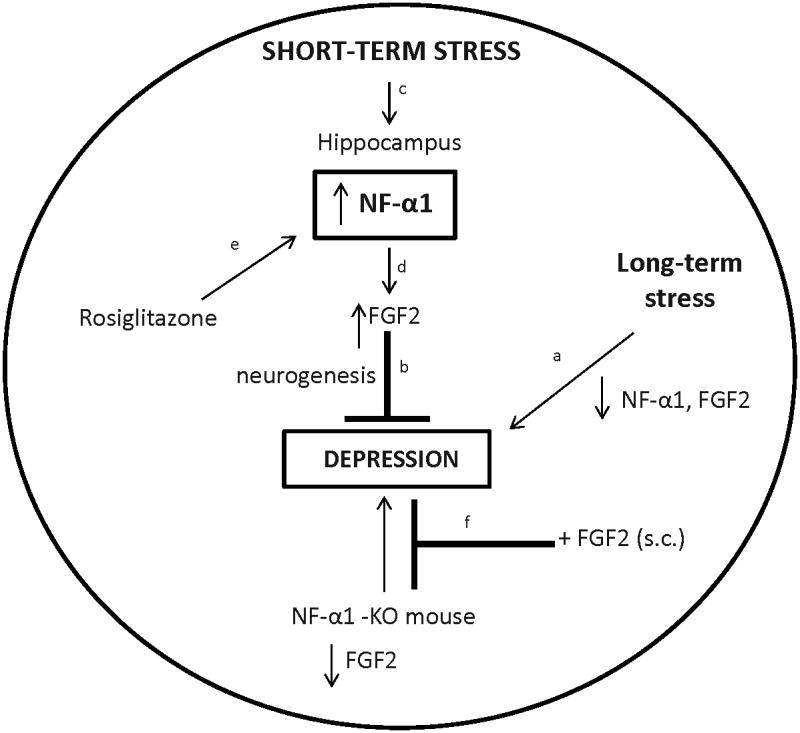

Here we have shown that NF-α1-mediated up-regulation of hippocampal FGF2 and neurogenesis prevents an onset of chronic stress-induced depressive-like behavior. Moreover, our results suggest that this mechanism can be induced pharmacologically with rosiglitazone, the PPARγ agonist that is clinically used to treat diabetes (see model in Fig. 6). The basis for the current studies initially evolved from our previous findings that NF-α1/CPE is increased in the hippocampus of mice subjected to short-term 7-day CRS, in part through glucocorticoid activation of the glucocorticoid regulatory element on the NF-α1/CPE promoter 30. Further support came from our preliminary gene array experiments showing that NF-α1/CPE treatment of cultured hippocampal neurons induced the expression of a member of the FGF family, FGF 4 (supplementary Fig. S10) with subsequent studies showing up-regulation of FGF2, but not BDNF 21.

Figure 6. Model depicting role of NF-α1 in anti depressive activity during stress.

aLong-term chronic stress leads to loss of NF-α1 and FGF2 in the hippocampus and depressive-like behaviors, that can be brescued by peripheral administration of FGF2. cShort-term chronic stress leads to an increase in NF-α1 expression in the hippocampus which dup-regulates FGF2 expression to promote neurogenesis and prevent depressive-like responses. eRosi up-regulates NF-α1 expression which in turn drives FGF2 expression in the hippocampus. f Mice lacking NF-α1 have diminished FGF2 levels in the hippocampus and exhibit depressive-like behavior that can be rescued by FGF2.

aThis study, b Turner CA et al.6; Elsayed M et al.20, c This study and Murthy SR et al.30, d-f This study.

Both NF-α1 and FGF2 are spatially and functionally linked not only because their expression overlaps in the CA1-3 pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus, but also because NF-α1 can act as a neurotrophic factor in an autocrine/paracrine fashion to up-regulate FGF2 expression (Fig. 3). Also, there is a concomitant increase of NF-α1 and FGF2 in the hippocampus of mice subjected to short-term CRS (Fig. 1A, B) suggestive of a dynamic link in vivo. Our cell biological studies using cultured hippocampal neurons treated with purified recombinant NF-α1 indicated a direct effect of NF-α1 in driving FGF2 expression. This regulation involves the NF-α1-activated ERK signaling pathway (Fig. 4F), followed by translocation of the transcription factor Sp1 from the cytoplasm into the nucleus (supplementary Fig. S8), resulting in an increase in transcription of FGF2 mRNA (Fig. 4G) and translation to several isoforms (24 kD, 21 kD and 17 kD) of the FGF2 protein (Fig. 4D, E). The 24 kD isoform was secreted from hippocampal neurons into the medium, similar to that observed from cardiac non-myocytes 41, however, the 21 kD and 17 kDa isoforms were not detected in the medium. Although we could not detect the 17 kD FGF2 isoform by Western blot in the medium, possibly because the levels were too low, this isoform is known to be preferentially exported from cells 42, 43. All 3 isoforms are derived from a single RNA, found in rodent and human brain. They are differentially expressed during development and after experimental interventions, and they have various neurotrophic effects 42, 44-46.

The mice after short-term CRS exhibited an increase in neurogenesis in the hippocampus as shown by the increase in DCX mRNA, a specific marker of immature neurons (Fig. 1C). Numerous reports indicate that neurogenesis in the SGZ mitigates antidepressive effects, although not in all cases, depending upon the stress paradigm 27. Thus, our data have demonstrated that short-term CRS increases NF-α1, which then drives the up-regulation of FGF2 expression and neurogenesis in the SGZ to prevent the onset of depressive-like behavior onset (Fig. 6). In contrast, with prolonged CRS (6 h/day) for 21 days, there was a significant decrease in NF-α1 concomitant with reduced FGF2 levels in the hippocampus (Fig. 1D, E), and these effects were related to the onset of depressive-like behavior in these mice (supplementary Fig. S1A, Fig. 6). Other investigators have also reported that prolonged chronic stress in rats and mice reduces FGF2 in the hippocampus, leading to depressive-like behavior 19, although the mechanism or up-stream regulator responsible for the down-regulation of FGF2 expression was not identified. The decreased expression of NF-α1 in vivo may, in part, be caused by prolonged glucocorticoid exposure. It is well known that glucocorticoids show biphasic effects in the nervous system with stress, resulting in neuronal survival or damage depending upon the dose and duration of time exposed 47. Indeed, ex vivo experiments in hippocampal neurons and pituitary cells in culture have shown that dexamethasone can increase or decrease NF-α1/CPE expression 30. Additionally, we have shown that NF-α1 is a neuroprotective molecule 21 and stressing NF-α1-KO mice leads to neurodegeneration in the hippocampus 26, 34. Hence decreased NF-α1 after prolonged CRS could lead to continuous neuronal changes including neuronal degeneration as reported by others 48. Our study indicates that a critical elevated level of hippocampal NF-α1 is required to drive FGF2 expression to prevent the onset of depressive-like behavior during short-term CRS. Thus NF-α1 is a key factor in the transition from the non-depressive to the depressive state associated with short- and long-term CRS, respectively.

Further evidence that NF-α1 plays a pivotal role in antidepressive-like activity is based on our studies using the NF-α1-KO mice. Mice deficient in NF-α1 showed overall decreased levels of FGF2 in the CA1 and CA2 hippocampus and in the fasciolarum cinereum (FC). Consistent with other rodent models of depression that have reduced FGF2 levels, the NF-α1-KO mice exhibited depressive-like behavior as demonstrated by the sucrose preference test and enhanced immobility in the forced swim test (Fig. 3A); a behavior that was completely rescued after daily peripheral injections of recombinant human 17 kD FGF2 for 30 days. This peripherally injected FGF2 most likely acts centrally since FGF2 can cross the blood-brain barrier 49, 50. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that it may also contribute to the alleviation of the depressive-like behavior by activating immune cells to release cytokines, such as IL10 which has been reported to ameliorate depressive symptoms in mice and is decreased in humans diagnosed with MDD 8, 51, 52. Another interesting finding is that the 24 kD and the 17 kD isoforms of FGF2 were virtually absent, but not the 21 kD (Fig. 2A,B) isoform, in the NF-α1-KO mice, providing supporting evidence for a functional connection between NF-α1 and the 24 kD and 17 kD FGF2 isoforms and antidepressive activity. Additionally, NF-α1-HET mice showing decreased 24 kD and 17 kD FGF2 levels, but not reduced 21 kD FGF2 compared to WT mice, also displayed depressive-like behavior, further supporting the importance of these two FGF2 isoforms for protection from depression.

Neuroprogenitor numbers were similar between WT and NF-α1-KO mice (supplementary Fig. S5), but the latter showed fewer immature neurons. However, peripheral administration of FGF2 to the NF-α1-KO mice led to increased neurogenesis (Fig. 3C, D) and cell proliferation (supplementary Fig. S7) in the dentate gyrus. This increased neurogenesis could be the result of increased differentiation of stem cells to progenitors, increased rate of proliferation and/or increased survival of progenitors mediated by FGF2. FGF2's effects on cell proliferation may not be limited to neurons, but may include glial cells, which have been shown to have an effect on depressive-like behavior 20. Indeed, peripheral administration of FG2 to rats is reported to promote the generation of new neurons and astrocytes in the hippocampus which may decrease anxiety behavior 53.

Consistent with the literature, this increase in neurogenesis can mitigate the depressive-like behavior in the NF-α1-KO mice after FGF2 treatment 54-56. It is also interesting that peripheral administration of FGF2 for 30 days did not enhance neurogenesis or cell proliferation in the SGZ of WT mice, suggestive of a homeostatic mechanism that prevents excessive neuronal differentiation or cell proliferation which might lead to abnormal pathology. This finding is noteworthy when developing antidepressants that stimulate FGF2 biosynthesis in the brain.

Finally, our studies suggest that developing drugs that up-regulate NF-α1 expression, which in turn induces FGF2 expression and neurogenesis in the hippocampus, is a potentially a useful therapeutic approach for treating depression. Our analysis of the cpe/NF-α1 promoter (supplementary Fig. S9) identified putative binding sites for PPARγ, a nuclear receptor and adipocyte-specific transcription factor, for which Rosi is a potent agonist. Rosi (Avandia™), which belongs to the thiazolidinediones (TZDs) class of drugs, has been used to treat diabetes and more recently it has been found to reverse the depressive-like behavior found in db/db diabetic mice 38. Additionally, rats given Rosi in their diet also show reduced depressive-like behavior in the forced swim test 28. Similarly, in a pilot study of patients with insulin resistance and unipolar or bipolar depression, treatment with Rosi demonstrated a significant decline in the severity of depression prior to the anti-diabetic actions of the drug 29. Indeed, it has been previously demonstrated that Rosi can influence the levels of PPARγ in neurons and that this interaction is at least partially responsible for anti-diabetic effects of TZDs 57. Our study has demonstrated that Rosi treatment of hippocampal neurons increased FGF2 in a NF-α1-dependent manner, and that Rosi-fed mice showed increased expression of NF-α1 and enhanced neurogenesis as evidenced by increased DCX mRNA expression in the hippocampus (Fig. 5). While we observed an increase in FGF2 mRNA with Rosi treatment ex vivo, we did not detect an increase in FGF2 in vivo in mouse hippocampus. It is possible that over a 3-wk period of Rosi administration, hippocampal FGF2 mRNA expression may have been up-regulated and then returned to baseline levels once neurogenesis has been induced, especially since the mice were not subjected to CRS. Our findings suggest a mechanism by which Rosi can reduce depressive-like behaviors in certain strains of diabetic mice and in humans through activation of the NF-α1-FGF2 pathway in the hippocampus in vivo. This observation raises the possibility that pharmacological agents, such as Rosi, can activate the NF-α1-FGF2 pathway to increase neurogenesis and it may offer an alternative approach to drugs that primarily target monoaminergic systems which are not always efficacious for treating MDD in some patients 27. Indeed, a strategy to enhance neurogenesis to treat anxiety disorders which can be comorbid with depression has previously been proposed, but no drug which accomplishes this effect has been reported 58.

In conclusion our study has identified NF-α1 as a key regulator of the onset of depressive-like behavior. We have determined that NF-α1 exerts a preventive effect on depressive-like behavior and this occurs through the hippocampal-adrenal axes to establish allostasis after short-term CRS by enhancing FGF2 expression and neurogenesis in the SGZ. Reduction of FGF2 with prolonged CRS or the absence of NF-α1 as in the NF-α1-KO mouse results in down-regulation of hippocampal FGF2 expression, leading to the development of depressive-like behavior, which can be rescued by peripheral administration of FGF2. Thus our study has elucidated a new physiological NF-α1-FGF2 pathway that is activated in the hippocampus during stress to prevent the onset of depressive-like behavior. Finally, our identification of rosiglitazone, a drug that functions by activating the NF-α1-FGF2 pathway to enhance neurogenesis and normalize depressive-like behavior provides a proof-of-concept for a new approach as an alternative to traditional monoamine-based antidepressants for treating MDD and other related disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Institutes of Health, USA and in part by National Institutes of Health grant HD36015 (W.C.W.) and the American Diabetes Association Award 7-13-BS-089 (B.L-C). We thank Lynne Holtzclaw, Dr. Vincent Schram in the MIC at NICHD for their help in the immunocytochemistry and confocal microscopy, Dr. Cheol Lee (Program on Genomics of Differentiation, NICHD) for his helpful discussions on markers for detecting neurogenesis in the hippocampus, Drs. Zhihong Jiang and Lee Eiden (NIMH) for help with the sucrose preference test. We also thank the following people from the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center: Theodore Rhodes and Christopher Means for helping with the daily restraint and forced swim tests. Thanks also to Dr. Chris McBain (NICHD), Dr. Owen Rennert (NICHD), Dr. Harold Gainer (NINDS) and Dr. Hao Yang Tan (Lieber Institute for Brain Development, Johns Hopkins University) for critical reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CPE

carboxypeptidase E

- NF-α1

neurotrophic factor-α1

- FGF2

fibroblast growth factor 2

- GEMSA

guanidino-ethyl-mercapto-succinic acid

- CRS

chronic restraint stress

- CPE-KO

carboxypeptidase E knock out

- WT

wide type

- HET

heterozygous

- DCX

doublecortin

- Rosi

rosiglitazone

Footnotes

Author contributions: Y.C., R.M.R., S.A., B. L-C., W.C.W., Y.P.L. designed the research ; Y.C., R.M.R., D.K.A., V.S., S.R.K.M., E.T. ; conducted the research, Y.C., R.M.R., V.S., S.R.K.M., E.T., N.X.C., W.C.W., Y.P.L. analyzed the data; Y.C., W.C.W., Y.P.L. wrote the paper.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare there is no conflict of interest to disclose.

Supplementary information: Supplementary information is available at Molecular Psychiatry's website

References

- 1.van Praag HM. Can stress cause depression? The world journal of biological psychiatry : the official journal of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry. 2005;6 Suppl 2:5–22. doi: 10.1080/15622970510030018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maes M, M HY. Psychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress. Raven Press; New York: 1994. The serotonin hypothesis of major depression. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schildkraut JJ. The catecholamine hypothesis of affective disorders: a review of supporting evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 1965;122(5):509–522. doi: 10.1176/ajp.122.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang C, Salton SR. The Role of Neurotrophins in Major Depressive Disorder. Transl Neurosci. 2013;4(1):46–58. doi: 10.2478/s13380-013-0103-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krishnan V, Nestler EJ. The molecular neurobiology of depression. Nature. 2008;455(7215):894–902. doi: 10.1038/nature07455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner CA, Watson SJ, Akil H. The fibroblast growth factor family: neuromodulation of affective behavior. Neuron. 2012;76(1):160–174. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duman RS, Monteggia LM. A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(12):1116–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voorhees JL, Tarr AJ, Wohleb ES, Godbout JP, Mo X, Sheridan JF, et al. Prolonged restraint stress increases IL-6, reduces IL-10, and causes persistent depressive-like behavior that is reversed by recombinant IL-10. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McEwen BS. The neurobiology of stress: from serendipity to clinical relevance. Brain Res. 2000;886(1-2):172–189. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02950-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duman RS, Malberg J, Thome J. Neural plasticity to stress and antidepressant treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46(9):1181–1191. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warner-Schmidt JL, Duman RS. Hippocampal neurogenesis: opposing effects of stress and antidepressant treatment. Hippocampus. 2006;16(3):239–249. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kempton MJ, Salvador Z, Munafo MR, Geddes JR, Simmons A, Frangou S, et al. Structural neuroimaging studies in major depressive disorder. Meta-analysis and comparison with bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(7):675–690. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnone D, McKie S, Elliott R, Juhasz G, Thomas EJ, Downey D, et al. State-dependent changes in hippocampal grey matter in depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;18(12):1265–1272. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boldrini M, Underwood MD, Hen R, Rosoklija GB, Dwork AJ, John Mann J, et al. Antidepressants increase neural progenitor cells in the human hippocampus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(11):2376–2389. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reif A, Fritzen S, Finger M, Strobel A, Lauer M, Schmitt A, et al. Neural stem cell proliferation is decreased in schizophrenia, but not in depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11(5):514–522. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Djavadian RL. Serotonin and neurogenesis in the hippocampal dentate gyrus of adult mammals. Acta neurobiologiae experimentalis. 2004;64(2):189–200. doi: 10.55782/ane-2004-1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sen S, Duman R, Sanacora G. Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor, depression, and antidepressant medications: meta-analyses and implications. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(6):527–532. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turner CA, Clinton SM, Thompson RC, Watson SJ, Jr, Akil H. Fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF2) augmentation early in life alters hippocampal development and rescues the anxiety phenotype in vulnerable animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(19):8021–8025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103732108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner CA, Calvo N, Frost DO, Akil H, Watson SJ. The fibroblast growth factor system is downregulated following social defeat. Neurosci Lett. 2008;430(2):147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elsayed M, Banasr M, Duric V, Fournier NM, Licznerski P, Duman RS. Antidepressant effects of fibroblast growth factor-2 in behavioral and cellular models of depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(4):258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng Y, Cawley NX, Loh YP. Carboxypeptidase E/NFα1: A New Neurotrophic Factor against Oxidative Stress-Induced Apoptotic Cell Death Mediated by ERK and PI3-K/AKT Pathways. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e71578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fricker LD, Snyder SH. Enkephalin convertase: purification and characterization of a specific enkephalin-synthesizing carboxypeptidase localized to adrenal chromaffin granules. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1982;79(12):3886–3890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.12.3886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hook VY, Eiden LE, Brownstein MJ. A carboxypeptidase processing enzyme for enkephalin precursors. Nature. 1982;295(5847):341–342. doi: 10.1038/295341a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodriguiz RM, Wilkins JJ, Creson TK, Biswas R, Berezniuk I, Fricker AD, et al. Emergence of anxiety-like behaviours in depressive-like Cpefat/fat mice. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S1461145713000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cawley NX, Wetsel WC, Murthy SR, Park JJ, Pacak K, Loh YP. New roles of carboxypeptidase E in endocrine and neural function and cancer. Endocr Rev. 2012;33(2):216–253. doi: 10.1210/er.2011-1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woronowicz A, Cawley NX, Loh YP. Carbamazepine prevents hippocampal neurodegeneration in mice lacking the neuroprotective protein, carboxypetidase E. Clinic Pharmacol Biopharmaceut. 2013 doi: 10.4172/2167-065X.S1-002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berton O, Nestler EJ. New approaches to antidepressant drug discovery: beyond monoamines. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(2):137–151. doi: 10.1038/nrn1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eissa Ahmed AA, Al-Rasheed NM, Al-Rasheed NM. Antidepressant-like effects of rosiglitazone, a PPARgamma agonist, in the rat forced swim and mouse tail suspension tests. Behav Pharmacol. 2009;20(7):635–642. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328331b9bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasgon NL, Kenna HA, Williams KE, Powers B, Wroolie T, Schatzberg AF. Rosiglitazone add-on in treatment of depressed patients with insulin resistance: a pilot study. ScientificWorldJournal. 2010;10:321–328. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murthy SR, Thouennon E, Li WS, Cheng Y, Bhupatkar J, Cawley NX, et al. Carboxypeptidase E Protects Hippocampal Neurons During Stress in Male Mice by Up-Regulating Pro-Survival BCL2 Protein Expression. Endocrinology. 2013;154(9):3284–3293. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meerlo P, Easton A, Bergmann BM, Turek FW. Restraint increases prolactin and REM sleep in C57BL/6J mice but not in BALB/cJ mice. American journal of physiology Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2001;281(3):R846–854. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.3.R846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willner P, Towell A, Sampson D, Sophokleous S, Muscat R. Reduction of sucrose preference by chronic unpredictable mild stress, and its restoration by a tricyclic antidepressant. Psychopharmacology. 1987;93(3):358–364. doi: 10.1007/BF00187257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukui M, Rodriguiz RM, Zhou J, Jiang SX, Phillips LE, Caron MG, et al. Vmat2 heterozygous mutant mice display a depressive-like phenotype. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27(39):10520–10529. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4388-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woronowicz A, Koshimizu H, Chang SY, Cawley NX, Hill JM, Rodriguiz RM, et al. Absence of carboxypeptidase E leads to adult hippocampal neuronal degeneration and memory deficits. Hippocampus. 2008;18(10):1051–1063. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cawley NX, Zhou J, Hill JM, Abebe D, Romboz S, Yanik T, et al. The carboxypeptidase E knockout mouse exhibits endocrinological and behavioral deficits. Endocrinology. 2004;145(12):5807–5819. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jimenez SK, Sheikh F, Jin Y, Detillieux KA, Dhaliwal J, Kardami E, et al. Transcriptional regulation of FGF-2 gene expression in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovascular research. 2004;62(3):548–557. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang W, Pan Q, Sun F, Ma J, Tang S, Le K, et al. Involvement of Sp1 binding sequences in basal transcription of the rat fibroblast growth factor-2 gene in neonatal cardiomyocytes. Life Sci. 2009;84(13-14):421–427. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharma AN, Elased KM, Lucot JB. Rosiglitazone treatment reversed depression- but not psychosis-like behavior of db/db diabetic mice. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26(5):724–732. doi: 10.1177/0269881111434620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shockley KR, Lazarenko OP, Czernik PJ, Rosen CJ, Churchill GA, Lecka-Czernik B. PPARgamma2 nuclear receptor controls multiple regulatory pathways of osteoblast differentiation from marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2009;106(2):232–246. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Czeh B, Michaelis T, Watanabe T, Frahm J, de Biurrun G, van Kampen M, et al. Stress-induced changes in cerebral metabolites, hippocampal volume, and cell proliferation are prevented by antidepressant treatment with tianeptine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(22):12796–12801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211427898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santiago JJ, Ma X, McNaughton LJ, Nickel BE, Bestvater BP, Yu L, et al. Preferential accumulation and export of high molecular weight FGF-2 by rat cardiac non-myocytes. Cardiovascular research. 2011;89(1):139–147. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Florkiewicz RZ, Baird A, Gonzalez AM. Multiple forms of bFGF: differential nuclear and cell surface localization. Growth Factors. 1991;4(4):265–275. doi: 10.3109/08977199109043912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schiera G, Proia P, Alberti C, Mineo M, Savettieri G, Di Liegro I. Neurons produce FGF2 and VEGF and secrete them at least in part by shedding extracellular vesicles. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2007;11(6):1384–1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00100.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grothe C, Schulze A, Semkova I, Muller-Ostermeyer F, Rege A, Wewetzer K. The high molecular weight fibroblast growth factor-2 isoforms (21,000 mol. wt and 23,000 mol. wt) mediate neurotrophic activity on rat embryonic mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons in vitro. Neuroscience. 2000;100(1):73–86. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00247-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meisinger C, Grothe C. Differential expression of FGF-2 isoforms in the rat adrenal medulla during postnatal development in vivo. Brain Res. 1997;757(2):291–294. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meisinger C, Grothe C. Differential regulation of fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-2 and FGF receptor 1 mRNAs and FGF-2 isoforms in spinal ganglia and sciatic nerve after peripheral nerve lesion. J Neurochem. 1997;68(3):1150–1158. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68031150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abraham IM, Meerlo P, Luiten PG. Concentration dependent actions of glucocorticoids on neuronal viability and survival. Dose-response : a publication of International Hormesis Society. 2006;4(1):38–54. doi: 10.2203/dose-response.004.01.004.Abraham. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uno H, Tarara R, Else JG, Suleman MA, Sapolsky RM. Hippocampal damage associated with prolonged and fatal stress in primates. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1989;9(5):1705–1711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-05-01705.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jin K, LaFevre-Bernt M, Sun Y, Chen S, Gafni J, Crippen D, et al. FGF-2 promotes neurogenesis and neuroprotection and prolongs survival in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(50):18189–18194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506375102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wagner JP, Black IB, DiCicco-Bloom E. Stimulation of neonatal and adult brain neurogenesis by subcutaneous injection of basic fibroblast growth factor. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1999;19(14):6006–6016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-06006.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dhabhar FS, Burke HM, Epel ES, Mellon SH, Rosser R, Reus VI, et al. Low serum IL-10 concentrations and loss of regulatory association between IL-6 and IL-10 in adults with major depression. Journal of psychiatric research. 2009;43(11):962–969. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mesquita AR, Correia-Neves M, Roque S, Castro AG, Vieira P, Pedrosa J, et al. IL-10 modulates depressive-like behavior. Journal of psychiatric research. 2008;43(2):89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perez JA, Clinton SM, Turner CA, Watson SJ, Akil H. A new role for FGF2 as an endogenous inhibitor of anxiety. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29(19):6379–6387. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4829-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eisch AJ, Petrik D. Depression and hippocampal neurogenesis: a road to remission? Science. 2012;338(6103):72–75. doi: 10.1126/science.1222941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Santarelli L, Saxe M, Gross C, Surget A, Battaglia F, Dulawa S, et al. Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science. 2003;301(5634):805–809. doi: 10.1126/science.1083328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Snyder JS, Soumier A, Brewer M, Pickel J, Cameron HA. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis buffers stress responses and depressive behaviour. Nature. 2011;476(7361):458–461. doi: 10.1038/nature10287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu M, Sarruf DA, Talukdar S, Sharma S, Li P, Bandyopadhyay G, et al. Brain PPAR-gamma promotes obesity and is required for the insulin-sensitizing effect of thiazolidinediones. Nature medicine. 2011;17(5):618–622. doi: 10.1038/nm.2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kheirbek MA, Klemenhagen KC, Sahay A, Hen R. Neurogenesis and generalization: a new approach to stratify and treat anxiety disorders. Nature neuroscience. 2012;15(12):1613–1620. doi: 10.1038/nn.3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.