Abstract

Predictors of the placebo response (PR) in randomized controlled trials (RCT) have been searched for ever since RCT have become the standard for testing novel therapies and age and gender are routinely documented data in all trials irrespective of the drug tested, its indication, and the primary and secondary endpoints chosen. To evaluate whether age and gender have been found to be reliable predictors of the placebo response across medical subspecialties, we extracted 75 systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-regressions performed in major medical areas (neurology, psychiatry, internal medicine) known for high placebo response rates. The literature database used contains approximately 2500 papers on various aspects of the genuine placebo response. These ‘meta-analyses’ were screened for statistical predictors of the placebo response across multiple RCT, including age and gender, but also other patient-based and design-based predictors of higher PR rates. Retrieved papers were sorted for areas and disease categories. Only 15 of the 75 analyses noted an effect of younger age to be associated with higher PR, and this was predominantly in psychiatric conditions but not in depression, and internal medicine but not in gastroenterology. In only 3 analyses female gender was associated with higher PR. Among the patient-based predictors, the most frequently noted factor was lower symptom severity at baseline, and among the design-based factors, it was a randomization ratio that selected more patients to drugs than to placebo, more frequent study visits, and more recent trials that were associated with higher placebo response rates. While younger age may contribute to the placebo response in some conditions, sex does not. There is currently no evidence that the placebo response is different in the elderly. Placebo responses are, however markedly influenced by the symptom severity at baseline, and by the likelihood of receiving active treatment in placebo-controlled trials.

Keywords: placebo response, age, sex, randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses

Introduction

Since the introduction of double-blinded and randomized placebo-controlled trials (RCT) in pharmacology and drug development in the middle of the last century, attempts have been made to identify and characterize patients that respond to placebo application with symptom improvement during an RCT (1). At the same time, ethical concerns have requested to limit the number of patients exposed to placebo to a minimum and to provide the best treatment available to those seeking health care for acute and chronic conditions (2).

The consequences resulting from this dilemma are numerous design variants that were developed to overcome RCT limitations: single and multiple cross-over designs, placeboand drug run-in phases, randomized and blinded run-ins and withdrawals, enrichment designs with more patients randomized to the drug than to placebo, cluster randomization, step-wedge design, registry trials, Zelen design, and sequential parallel comparison designs, to name just a few (3). They all have advantages and pitfalls in minimizing the placebo effects in RCT (4).

At the same time, psychologists and trialists have attempted to profile placebo responders in RCT, with much less success than initially thought (5). Among the many personality traits that have been tested for prediction of placebo responses specifically in experimental settings, a few have been able to allow generalization across conditions and diseases (6), and certainly most – if not all – have never been tested in large-scale RCT for obvious reasons: if they would demonstrate an identifiable and substantial subset of patients that has to be excluded, this would pose the indication of the drug under testing at risk.

Biomarkers of the placebo response, especially genetic traits may be the future (e.g. COMT in IBS patients (7)), but currently the list is rather small (7-10) and it appears unlikely that a single genetic polymorphism, e.g. of the oxytocin pathway (11,12) may account for all placebo responses in all medical and clinical conditions.

Under these circumstances it is not surprising that age and gender issues have repeatedly been named as important contributors (mediators or moderators) to the placebo response in RCT, as they are recorded and documented in all RCT performed; especially the placebo response in different age groups has frequently been reviewed (13-15). We recently (16) screened the literature with respect to the question whether children and adolescents exhibit higher placebo responses than adults, and found at least some evidence to supporting this position. Experimental data however, devoted t this question does come to the opposite conclusion (17).

Very few data but mostly speculation does exist with respect to the question what happens to the placebo response in the elderly (18). A narrative review in this journal discusses potential outlines in general, however, does not come to a firm prospect and prediction (19), and experimental data, e.g. testing susceptibility to placebo analgesia procedures across the older age ranges do not exists.

Theoretically, one may assume three models: either the child-to-adolescent-to-adulthood decrease of the PR that has been proposed before (16) continues (Model 1), or it stabilizes and no further change in the PR is noted with reaching adult life (Model 2), or the function reverses (Model 3). Model 1 would use a ‘continuous learning’ assumption that blocks the placebo response in the elderly to operate due to a longer history of successful and failed medicinal interventions. Model 2 (stable PR once adulthood is reached) assumes the major driver of the PR to occur during childhood, when the learning capacity is maximal and expectations are the highest. Model 3 finally assumes a cognitive decline to occur with senescence that may also affect expectations for help to increase again. None of these models is currently supported by strong empirical evidence, and they may vary across diseases and systems.

To approach an answer to this question, we set-out to evaluate current evidence for a role of age - and gender – in re-analyses of RCT, either as systematic reviews, or as methodologically firm meta-analyses or meta-regressions. In addition to checking for age and gender contributions to the placebo response, we were interested in other patient or design-based factors that would be associated with higher placebo response across different medical conditions.

Methods

Since 2004 we searched PUBMED for articles using the search term ‘placebo’ both retrospectively and prospectively to select papers dealing with the placebo effect.

For all approximately 100.000 citations retrieved in 2004, we (KW, PE) screen their titles and abstracts retrospectively and excluded papers describing placebo-controlled trials of individual drugs and other medical interventions that ‘only’ assessed differences between drug and placebo for evaluation of therapeutic benefits of the therapy. We also excluded meta-analyses of placebo-controlled trials and respective reviews. After exclusion of letters and editorials, we were left with approximately 1,000 papers (or approximately 1% of all papers screened) that discussed different aspects of the placebo response and/or placebo effects in different medical and psychological subspecialties. These were predominantly experimental data (exploring the different mechanisms of the placebo response) and reviews, systematic reviews, re-analyses and meta-analyses of RCT data. PDFs of these papers were retrieved and stored into an ENDNOTE database.

Since 2004, we prospectively screen all papers published on a weekly basis ever since (total paper count: 170,855 as of April 4, 2014) using the same search term ‘placebo’. In 2010, we added the search term ‘nocebo’ (230 citations as of April 4, 2014). We occasionally added papers that explored and discussed psychosocial contributions to placebo-like effects even without using the term placebo, e.g. (20).

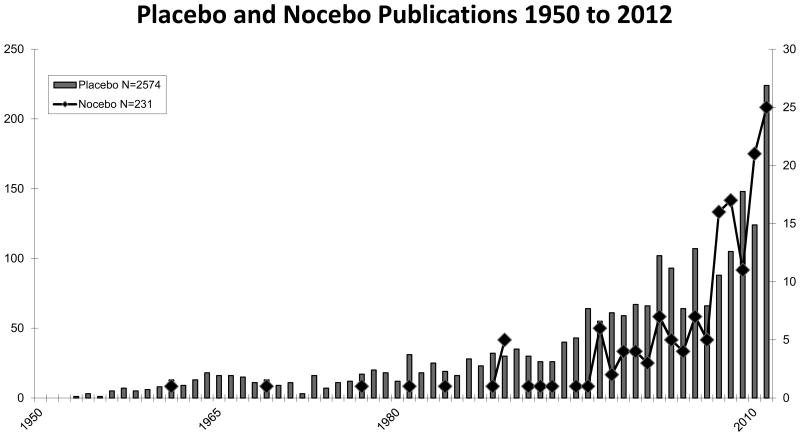

This database currently contains approximately 2,500 papers of various aspects of the placebo and nocebo response in medicine and beyond. The distribution of these papers on the genuine placebo and nocebo effects between 1960 and 2014 is depicted in Figure 1, and demonstrates an exponential increase, similar to the increase seen in the remaining placebo literature.

Figure 1.

Numbers of yearly publication of genuine papers on the placebo and nocebo response in PUBMED between 1950 and 2012.

This database was hand-searched by all authors for systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-regression of the placebo effects and its determinants (mediators, moderators) in various medical specialties, supplemented by papers found in these papers and entered into our database. This way, we identified 75 systematic reviews, meta-analyses and meta-regressions that were used for this systematic review.

Each of these papers was then screened for whether age and gender were included in the analysis, and whether they were explicitly found as moderators of the placebo response in the placebo arm of respective trials, irrespective of the type of statistical analysis (ANOVA, regression, multiple regression, meta-regression) that was used to identify it. To not over- or underestimate the respective findings, we categorized the potential contribution of age and sex with ‘yes’ or ‘no’ only, based to the individual papers' own evaluation.

We also noted whether and which other patient or design factors in the trials were found to contribute to the size of the placebo response.

Results

The 75 systematic reviews, meta-analyses and meta-regressions were sorted into 6 disease groups: neurological diseases (Parkinson's Disease, Restless-Leg Syndrome, epilepsy, excluding pain: 9 papers), pain syndromes (migraine, neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, excluding visceral pain: 13 papers), psychiatric diseases (schizophrenia, mania, psychosis, ADHD, addiction, excluding depression: 17 papers), depression (15 papers), gastrointestinal disorders (irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia, inflammatory bowel diseases, 12 papers), and other mixed disorders (asthma, overactive bladder, hypertension, allergy, chronic fatigue, sleep problems, 10 papers); one paper mate-analyzed two diseases.

It should be noted that these 75 analyses (which we will refer to collectively as ‘meta-analyses’ in the following) used quite different methodologies for their respective analyses on the one hand, which makes a direct comparison difficult if not impossible. On the other hand, the papers selected from the body of literature (mostly randomized, placebo-controlled trials, sometimes including comparator trials with two or more drugs) may substantially overlap within a condition but were frequently based of different selection and quality criteria. It is therefore conceivable that in some conditions (e.g. in depression) similar mediators and moderators are reported by different analyses, while in other cases analyses may not have been able to replicate of previous analyses.

Furthermore, only a minority of all papers (n=20) were based on individual patient data available, while all other are referring to the published reports (or data reports to the drug approval authorities) that usually only contain means and standard deviations of the data on the age of patients, and percentage of males/females in the respective treatment groups.

Major findings within and across clinical conditions will subsequently be discussed for each of the medical subgroups, with a special emphasis of whether or not age and gender have been noted as contributing factors to the size of the placebo response.

Neurological trials (excluding pain)

Table 1 reports results from 9 meta-analyses in Parkinson's Disease (n=4), Restless-Leg Syndrome (n=2), and Epilepsy (n=3). Two Parkinson's Disease analyses noted higher PR with older age among adults (27,29), while of the two analyses that expressively investigated age aspects (children versus adults) in epilepsy, only one (22) could substantiate that the PR is double as high in children (19%) compared to adults (9.9%) while the other found the opposite (23). Only one of the 7 reports noted higher PR in females (25).

Table 1. Meta-analyses of RCTS in neurological disorders (RSL = Restless Leg Syndrome; n.r.= not reported; PR = placebo response).

| Author | Year | Ref. | N* | Disease | Age | Sex | PR is higher with | PR is also higher with … |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burneo | 2002 | 21 | 31 | Epilepsy | no | n.r. | No other factor identified | |

| Rheims | 2008 | 22 | 32 | Epilepsy | yes | no | lower age | No other factor identified |

| Schmidt | 2013 | 23 | 3* | Epilepsy | yes | no | higher age | lower baseline severity |

| Fulda | 2007 | 24 | 36 | RLS | no | no | longer trial duration | |

| Ondo | 2013 | 25 | 6* | RLS | no | yes | female sex | lower baseline severity, |

| Goetz | 2000 | 26 | 1* | Parkinsons | no | no | No other factor identified | |

| Goetz | 2008 | 27 | 2* | Parkinsons | yes | no | higher age | lower baseline severity |

| Goetz | 2008 | 28 | 11* | Parkinsons | no | no | higher baseline severity | |

| Ondo | 2007 | 29 | 2* | Parkinsons | yes | no | higher age | No other factor identified |

N: Number of studies analysed; an

indicates that individual data were available

Among the other factors identified to predict higher PR in more than one analysis are lower baseline severity of epilepsy, restless leg symptoms, and PD (23,25,27), but one analysis (28) found higher baseline severity to be associated with higher PR in PD.

Pain trials

The meta-analyses of pain trials across different pain conditions include migraine (n=6), neuropathic pain (n=3), and dental pain, osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and pain in pancreatitis (n=1 each) (Table 2). In none of the analyses, gender was noted as the predictor of the PR, and in only two migraine analyses (33,34) age was noted as a predictor.

Table 2. Meta-analyses of RCTS in pain disorders (DPN = Diabetic polyneuropathy, n.r. = not reported;PR = placebo response).

| Author | Year | Ref. | N | Disease | Age | Sex | PR is higher with … | PR is also higher with … |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diener | 1999 | 30 | 15 | Migraine | n.r. | n.r. | higher drug chance | |

| Macedo | 2006 | 31 | 98 | Migraine | no | no | European studies | |

| Macedo | 2008 | 32 | 32 | Migraine | n.r. | n.r. | European studies | |

| Ho | 2009 | 33 | 8 | Migraine | yes | no | lower age | lower prior triptan use |

| Sun | 2013 | 34 | 7 | Migraine | yes | n.r. | lower age | early response |

| Meissner | 2013 | 35 | 79 | Migraine | no | no | type of placebo | |

| Averbuch | 2001 | 36 | 16 | Dental pain | n.r. | n.r. | No other factor identified | |

| Quessy | 2008 | 37 | 35 | Neuropathic pain | n.r. | n.r. | higher drug chance | |

| Kamper | 2008 | 38 | 44 | Pain | n.r. | n.r. | No other factor identified | |

| Zhang | 2008 | 39 | 193 | Osteoarthritis | no | no | lower baseline severity | |

| Häuser | 2011 | 40 | 72 | Fibromyalgia | no | no | lower baseline severity | |

| Häuser | 2011 | 40 | 70 | DPN | no | no | lower baseline severity | |

| Capurso | 2012 | 41 | 7 | Pancreatitis | no | no | more study sites |

N: Number of studies analysed

Lower baseline pain intensity was noted as a predictor in 3 analyses (39,40). Among study characteristics, a higher chances for drugs resulted in higher PR in two instances (30,37), European studies were reported to have higher PR as compared to studies in the US (31,32), as were a higher number of study sites (41).

Psychiatric trials (excluding depression)

Of the 17 meta-analyses in psychiatric disorders, trials in schizophrenia (n=6) received the most attention, followed by addiction therapy (n=3), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (n=3), bipolar mania (n=2), and autism, binge-eating disorders (BED), and obsessive-compulsive disorder/anxiety (OCD)(n=1 each) (Table 3). Five analyses were based on individual data.

Table 3. Meta-analyses of RCTS in psychiatric disorders (OCD: obsessive compulsive disorder; ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; BED: Binge eating disorder, n.r. = not reported; PR = placebo response).

| Author | Year | Ref. | N* | Disease | Age | Sex | PR is higher with … | PR is also higher with … |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woods | 2005 | 42 | 32 | Schizophrenia | no | no | higher chance of drug | |

| Kemp | 2010 | 43 | 28 | Schizophrenia | n.r. | n.r. | lower baseline severity | |

| Mallinckrodt | 2010 | 44 | 27 | Schizophrenia | no | yes | female sex | higher change of drug |

| Chen | 2010 | 45 | 31 | Schizophrenia | yes | no | lower age | lower baseline severity |

| Potkin | 2011 | 46 | 3* | Schizophrenia | no | no | lower baseline severity | |

| Agid | 2013 | 47 | 50 | Psychosis | yes | no | lower age | higher baseline severity |

| King | 2013 | 48 | 1* | Autism, children | no | no | lower symptom severity | |

| Sysko | 2007 | 49 | 20 | Bipolar mania | n.r. | n.r. | recent studies | |

| Yildiz | 2011 | 50 | 38 | Bipolar mania | yes | yes | higher age, female sex | recent studies |

| Cohen | 2010 | 51 | 40 | OCD, anxiety | yes | no | lower age | lower baseline severity |

| Newcorn | 2009 | 52 | 10 | ADHD children | yes | no | lower age | medication naïve patients |

| Waxmonsky | 2011 | 53 | 2* | ADHD | yes | no | higher age (adults) | higher baseline severity (adults only) |

| Buitelaar | 2012 | 54 | 2* | ADHD adults | yes | no | lower age | higher baseline severity |

| Blom | 2014 | 55 | 10* | BED | no | no | lower baseline severity | |

| Green | 2010 | 56 | 107 | Smoking | n.r. | n.r. | no industry support | |

| Litten | 2013 | 57 | 48 | Alcohol | yes | n.r. | lower age | recent studies |

| Moore | 2012 | 58 | 28 | Addictions | n.r. | n.r. | No other factor identified |

N: Number of studies analysed; an

indicated availability of individual patient data

Eight analyses reported age-related differences in the PR, however with different trends: Younger age was associated with higher PR in schizophrenia (45,47), OCD (51), ADHD in children and adults (52,54), and treatment of alcohol dependence (57), while in bipolar mania and one adult ADHD analysis, higher placebo response was associated with higher age (50,53). Two analyses only noted higher PR in females (44,50).

Lower baseline severity of symptoms was the most frequently noted patient-based predictor of high PR (5 analyses (43,45,46,51,55) across all conditions) while in ADHD in adults, higher baseline severity was associated with higher PR (53,54), similar to schizophrenia (47). More recent trials produced higher PR (49,50,57), as did a higher randomization ratio to drug (42).

Depression trials

Depression trials represent the largest single clinical entity that has been meta-analyzed for predictors of the PR; in fact, increasing placebo response rates in more recent trials were noted first in depression (60) and mark the starting point for the increase in placebo research in the early years of the 21st century (see above, Figure 2).

The 15 meta-analyses included into Table 4 include 3 with individualized data (59,69,73).

Table 4. Meta-analyses of RCTS in depression (GAD: General anxiety disorder, PD: Panic disorder; MDD: major depression disorder; rTMS: repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; n.r. = not reported; PR = placebo response).

| Author | Year | Ref. | N* | Disease | Age | Sex | PR is higher with … | PR is also higher with … |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown | 1992 | 59 | 1* | Depression | no | no | lower baseline severity | |

| Walsh | 2002 | 60 | 75 | Depression | n.r. | n.r. | recent studies | |

| Khan | 2002 | 61 | 45 | Depression | n.r. | n.r. | higher baseline severity | |

| Evans | 2004 | 62 | 4 | Depression | no | no | symptom worsening before start | |

| Stein | 2006 | 63 | 12 | GAD, PD, MDD | no | no | European studies | |

| Kirsch | 2008 | 64 | 35 | Depression | no | n.r. | lower baseline severity | |

| Papakostas | 2008 | 65 | 182 | Depression | yes | n.r. | lower age (<65 yrs) | lower baseline severity |

| Bridge | 2009 | 66 | 12 | Depression, children | n.r. | no | lower baseline severity | |

| Brunoni | 2009 | 67 | 41 | Depression | no | no | rTMS as add-on therapy | |

| Sinyor | 2010 | 68 | 91 | Depression | n.r. | n.r. | higher chances for drug | |

| Hunter | 2010 | 69 | 1* | Depression | no | no | treatment naive patients | |

| Rutherford | 2011 | 70 | 11 | Depression, children | no | n.r. | higher number of study visits | |

| Gueorguiva | 2011 | 71 | 7 | Depression | no | no | No other factor identified | |

| Khin | 2011 | 72 | 81 | Depression | n.r. | n.r. | lower baseline severity | |

| Mancini | 2014 | 73 | 14* | Depression | no | n.r. | higher number of study visits |

N: Number of studies analysed; an

indicated availability of individual patient data

Only one analysis (65) noted an influence of age on the PR (higher PR in patients below age 65), none reported an influence of sex on the PR.

Among the patient-based characteristics of high PR, lower baseline severity (59,64-66,72) was noted as predictive, as was worsening of symptoms during screening and study start (62), and treatment naive patients (69). In contrast to most other meta-analyses, one analysis noted higher baseline severity of symptoms to be associated with higher PR (61).

More recent trials (60), a higher randomization ratio (68) and European studies (63) were linked to higher PR. Another design factor associated with higher PR was a higher number of study visits (70,73).

Trials in gastrointestinal disorders

Among gastrointestinal disorders, most frequently trials in the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) were meta-analyzed (n=4), followed by inflammatory bowel diseases (Crohn's Disease, CD; Ulcerative colitis, UC) (n=3), functional dyspepsia (FD) (n=2), and reflux disease (RD) and gastric and duodenal ulcers (n=1 each). Two analyses in FD were based on individualized data (81,82) (Table 5).

Table 5. Meta-analyses of RCTS in gastrointestinal disorders (IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IBS: irritable bowel syndrome; n.r. = not reported; PR = placebo response).

| Author | Year | Ref. | N* | Disease | Age | Sex | PR is higher with … | PR is also higher with … |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ilnyckyj | 1997 | 74 | 38 | IBD | n.r. | n.r. | higher number of study visits | |

| Su | 2004 | 75 | 21 | IBD | no | no | higher number of study visits | |

| Renna | 2008 | 76 | 16 | IBD | no | no | longer follow-up | |

| Pitz | 2005 | 77 | 84 | IBS | yes | no | lower age | higher number of study visits |

| Patel | 2005 | 78 | 45 | IBS | no | no | lower number of study visits | |

| Dorn | 2007 | 79 | 19 | IBS | no | no | higher number of study visits | |

| Ford | 2010 | 80 | 73 | IBS | no | no | European studies | |

| Talley | 2006 | 81 | 4* | Functional dyspepsia | no | no | inconsistent symptoms | |

| Enck | 2009 | 82 | 1* | Functional dyspepsia | no | no | improvement during run-in | |

| De Craen | 1999 | 83 | 79 | Duodenal ulcers | n.r. | n.r. | higher application frequency | |

| Yuan | 2009 | 84 | 36 | Gastric ulcers | no | n.r. | previous GI history | |

| Cremonini | 2010 | 85 | 24 | Reflux disease | no | no | non-erosive reflux disease |

N: Number of studies analysed; an

indicated availability of individual patient data

One analysis only noted a higher PR in younger patients (77), none reported gender differences in the PR.

Only a few disease and patient-related features predicted higher PR, especially inconsistent symptom pattern (81), symptom improvement during run-in (82), and a previous history of GI symptoms (84).

Among the design features analyzed, a higher number of study visits was predictive of higher placebo responses in UC (74), CD (75), IBS (77,79), while one report in IBS found high PR to be predicted by a lower number of office visits (78). Longer treatment follow-up (76) and higher frequency of drug application (83) were also predictive of the PR.

Trials in other diseases

Ten more meta-analyses report predictors from treatment trials for sleep problems (n=2), asthma (n=2), allergy (n=1), psoriasis (n=1), premenstrual syndrome (PMS) (n=1), chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) (n=1), hypertension (n=1) and overactive bladder (OAB) (n=1), of which 4 were based on individual data (Table 6).

Table 6. Meta-analyses of RCTS in other disorders (OAB: Overactive bladder; CFS: Chronic fatigue syndrome; PMS: Premenstrual syndrome; n.r. = not reported; n.a. = not applicable, PR = placebo response).

| Author | Year | Ref. | N* | Disease | Age | Sex | PR is higher with … | PR is also higher with … |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee | 2009 | 86 | 36 | OAB | n.r. | n.r. | lower baseline severity | |

| Thijs | 1990 | 87 | 1* | Hypertension | yes | n.r. | younger age | No other factor identified |

| Cho | 2005 | 88 | 29 | CFS | no | no | high intervention intensity | |

| Freeman | 1999 | 89 | 2* | PMS | yes | n.a. | younger age | No other factor identified |

| Lamel | 2012 | 90 | 31 | Psoriasis | n.r. | n.r. | higher drug chance | |

| Narkus | 2013 | 91 | 6 | Allergy | n.r. | n.r. | No other factor identified | |

| Kemeny | 2007 | 92 | 1* | Asthma | yes | no | younger age | No other factor identified |

| Wang | 2012 | 93 | 34 | Asthma | no | no | lower baseline severity | |

| McCall | 2003 | 94 | 5 | Sleep disorders | n.r. | n.r. | No other factor identified | |

| McCall | 2011 | 95 | 1* | Sleep disorders | yes | n.r. | younger age | No other factor identified |

N: Number of studies analysed; an

indicated availability of individual patient data

Four analyses noted higher PR in younger patients (87,89,92,95), while no study found an influence of gender on the PR.

A higher randomization ratio (90) was noted as a design factor driving higher PR in psoriasis, and lower symptom severity at baseline (86,93) as patient-based factor driving the PR.

Discussion

This systematic review of systematic reviews, meta-analyses and meta-regressions demonstrates both disease-specific as well as disease-unspecific factors driving the PR in RCT, and these factors are either patient-based or design-based.

Age and gender

Taken together, our analysis indicates that age and gender appear not to play a role for PR in RCT: only 3 of 74 analyses could identify a contribution of sex towards the PR, and only 15 of the analyses found that PR are higher in younger patients (mostly in psychiatric trials) while another 5 found the opposite. As we have seen especially in analyses involving children and adolescents with ADHD (52-54), these are based on a small number of studies included in the respective meta-analyses and therefore cannot outnumber the many more studies in adults that could not support this hypothesis. Even if the very young patients may show higher placebo response rates than adolescents and adults under specific circumstances (16), certainly among the models illustrated in Figure 1, model No. 2 is the most likely one: studies and analyses including the elderly (above 65 years) (65,87) could not substantiate a further decrease of the PR in this group beyond that of adults.

It is of importance to note that our analysis grossly ignores quality differences in the type of statistical analysis substantiating the findings in the different meta-analyses, and that most studies were based on aggregate (study level) data. For proper patient-related predictors – such as age and gender – metaanalytic approaches based on individual patient data would be more appropriate, as was the case in 20 of the 75 analyses. But even if we only consider only these 20 reports, a similar picture emerges: 5 analyses noted younger age to be associated with higher PR, while 4 found older age to be the driving factor of the PR, and 11 did not find a contribution of age at all. Whether access to individual patient data for more RCT (e.g. in central repository) would allow another conclusion, needs to be shown in the future but as long as access to individual drug trial data is predominantly controlled by the pharmaceutical industry this will remain hope only (96).

A question remains that we cannot answer at this stage: why are sometimes average PR rates higher in children with ADHD, depression, and autism when compared to overall PR rates in the same condition in adults? The answer is presumably of methodological nature: In RCT, the response in the placebo arm of drug trials is usually a compound effect of different factors such as spontaneous variation of symptoms, regression to the mean, and the specific PR due to expectations and learning (4). For the evaluation of the true drug benefit ‘above placebo’, separation of these factors is not necessary and is usually not performed. However, for the characterization of the ‘true’ PR it would be essential to include a ‘no treatment’ control group to identify the contribution of the natural course of the disease (3) to both the drug and the placebo treated patients. If done so (97), nearly half of the effect seen in the placebo arm of RCT can be attributed to spontaneous variation of symptoms. With respect to the contribution of age of children, adolescents, adults, and elderly to the PR, a necessary consequence would be to test whether spontaneous variation of symptoms is similar in these different age groups within a single clinical condition (e.g. asthma), which is rather unlikely (98). And even if so, the PR may still be higher in youth and women because of differences in pathophysiology.

While no-treatment controls are ethically questionable for serious medical conditions, an approximation of the size of spontaneous contribution to the PR in RCTs can be achieved using waiting-list controls that have their own methodological limitations (3) but are frequently conducted in non-drug trials, e.g. with psychotherapy (99): In one meta-analyses (100) it was shown that the effect of waiting improved baseline depression scores by 33%, while placebo administration accounted for a 40% improvement. In another study, spontaneous improvement during waiting was 15% of HAM baseline values after 4 to 8 weeks waiting, and 20% of patients would respond to a degree that would be regarded as significant clinical improvement (101). In the meta-analysis by Krogsboll (97), waiting contributed between 0 (insomnia) and 80% (depression) to the overall placebo effect across a variety of medical conditions.

Patient and disease-based factors

Among the patient-based predictors of the PR, the most prominent one that appears across all conditions and diseases except in gastrointestinal disorders is lower severity of the illness at baseline prior to randomization; this was noted in 18 analyses, and a few contrary reports come only from neurological and psychiatric disorders (28,47,53,54, 66). Usually, symptom severity is assessed via diagnostic criteria such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM), the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), the Inattention/Overactivity with Aggression (IOWA) Conners parent and teacher rating scales in ADHD, and the Rome criteria in IBS, and cut-off criteria are used to ease and standardize enrolment. However, for most of the diseases listed here, these are predominantly physician or patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures that are known to be susceptible to higher PR as compared to disease biomarkers (102,103), and also prone to manipulation during recruitment (104). Furthermore, it has been shown that (in depression) physician and patient rating of disease severity may vary substantially (105). The inclusion of patients with low symptom severity in RCT may also be in the interest of the drug industry (106) since it offers a larger market share once the drug has been approved.

Other patient-based or disease-based factors driving the PR have been noted occasionally in individual analyses, such as treatment naivety in migraine (33), ADHD (52), and depression (69), symptom worsening before the start of the study in depression (62), but symptom improvement during run-in (82) and inconsistent symptom pattern (61) in FD, and early response to therapy (34). It should be noted that in addition to the factors listed in the tables above, most studies noted more and other patient and design factors contributing to the PR.

Design-based factors

Three of the many factors identified in the meta-analyses stick out as prominent: more recently performed studies report higher PR rates than studies in the past (49,50,57,60), more study visits during the trial (70,73,74,75,77,79,83), and studies randomizing more patients to drug than to placebo (called unbalanced randomization) (30,37,42,68).

The first two are certainly correlated: Over the last 25 years, trial designs have changed substantially from cross-over to parallel design, from 4 weeks to 8 to 12 weeks and even longer (3), and patient monitoring during the trial has intensified, e.g. by using electronic monitoring systems, resulting in more contacts of patients with doctors and trial staff. This underlines the importance of doctor-patient communication as underlying mechanisms for PR, within and outside of clinical trials (3). Associated PR-driving factors are longer trial duration (24) and longer follow-up observations (76). It should be noted that the number of study visits was explicitly not a predictor of the PR response in pediatric trials in depression in children, while it was in adolescents and adults (70), indicating principle differences between children and adults. For children, the concept of ‘placebo by proxy’ has been put forward (107), but this need to be explored further also for adults.

It appears also that in some indication areas (migraine, depression, IBS) European studies have produced higher PR rates than studies in the US (31,32,63,80). Whether this reflects systematic differences in design characteristics between Europe and the US remains to be shown, but it may be linked to more study sites and the increase of multicenter trials (41) in Europe.

The other factor, unbalanced randomization, is of different nature but has been noted as early as 1999 (30). Recruiting more patients to drug than to placebo may be done for different reasons: for ethical reasons, to allow more patients to receive active treatment, for practical reasons to speed the recruitment process, or for pharmacological reasons, to test different drug doses or different drugs against a single placebo arm. This lowering of chances of patients to be randomized to placebo increases their expectations of subsequent symptom improvement and results in both higher drug as well as placebo responses and decreases the drug-placebo difference, e.g. in depression (65). This has also been confirmed in experimental studies, e.g. in Parkinson patients (108) and may be due to higher dopamine release as the underlying neurobiological reward mechanism (109).

We need to acknowledge limitations of our analysis. One is that we may have missed relevant information in single RCT that may have – among others - analyzed determinants of the PR in addition to evaluation drug-placebo differences. We restricted ourselves to the analysis of papers (systematic reviews, meta-analyses, meta-regressions) that explicitly focused on the PR and quantified it, because otherwise we would not have been able to cover all medical subspecialties, simply due to the sheer number of RCT that have been published (more than 100,000). We also grossly ignored quality differences in the selected analyses and handled them all rather equally to extract predictor information, despite the fact that extraction errors in meta-analyses are known to be high (110). This however, allowed us to attempt to screen the whole range of potential predictors of the PR – a quantification of these factors was never intended and may even be impossible. Finally, we focused on age and sex as moderators of the PR for this review and listed only one major patient or design-based predictor per analyses for illustration reasons – further analyses for single medical subspecialties will show whether or not our listing is unbalanced or incomplete, and likewise, whether age and gender have different impact across different conditions.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

References

- 1.de Craen AJ, Kaptchuk TJ, Tijssen JG, Kleijnen J. Placebos and placebo effects in medicine: historical overview. J R Soc Med. 1999;92:511–515. doi: 10.1177/014107689909201005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller FG, Colloca L. The placebo phenomenon and medical ethics: rethinking the relationship between informed consent and risk-benefit assessment. Theor Med Bioeth. 2011;32:229–243. doi: 10.1007/s11017-011-9179-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weimer K, Enck P. Traditional and innovative experimental and clinical trial designs – advantages and pitfalls. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-44519-8_14. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enck P, Bingel U, Schedlowski M, Rief W. The placebo response in medicine: minimize, maximize or personalize? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:191–204. doi: 10.1038/nrd3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaptchuk TJ, Kelley JM, Deykin A, Wayne PM, Lasagna LC, Epstein IO, Kirsch I, Wechsler ME. Do “placebo responders” exist? Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29:587–595. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horing B, Weimer K, Enck P. Predictors of placebo effects across symptoms and symptom modalities. Psychosom Med. 2014;76:A29. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall KT, Lembo AJ, Kirsch I, Ziogas DC, Douaiher J, Jensen KB, Conboy LA, Kelley JM, Kokkotou E, Kaptchuk TJ. Catechol-O-methyltransferase val158met polymorphism predicts placebo effect in irritable bowel syndrome. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furmark T, Appel L, Henningsson S, Ahs F, Faria V, Linnman C, Pissiota A, Frans O, Bani M, Bettica P, Pich EM, Jacobsson E, Wahlstedt K, Oreland L, Långström B, Eriksson E, Fredrikson M. A link between serotonin-related gene polymorphisms, amygdala activity, and placebo-induced relief from social anxiety. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13066–13074. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2534-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leuchter AF, McCracken JT, Hunter AM, Cook IA, Alpert JE. Monoamine oxidase a and catechol-o-methyltransferase functional polymorphisms and the placebo response in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29:372–377. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181ac4aaf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu R, Gollub RL, Vangel M, Kaptchuk T, Smoller JW, Kong J. Placebo analgesia and reward processing: Integrating genetics, personality, and intrinsic brain activity. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014 doi: 10.1002/hbm.22496. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enck P, Klosterhalfen S. The story of O--is oxytocin the mediator of the placebo response? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:347–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessner S, Sprenger C, Wrobel N, Wiech K, Bingel U. Effect of oxytocin on placebo analgesia: a randomized study. JAMA. 2013;310:1733–1735. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franconi F, Campesi I, Occhioni S, Antonini P, Murphy MF. Sex and gender in adverse drug events, addiction, and placebo. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2012;(214):107–126. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-30726-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tedeschini E, Levkovitz Y, Iovieno N, Ameral VE, Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Efficacy of antidepressants for late-life depression: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of placebo-controlled randomized trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:1660–1668. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10r06531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rutherford BR, Tandler J, Brown PJ, Sneed JR, Roose SP. Clinic Visits in Late-Life Depression Trials: Effects on Signal Detection and Therapeutic Outcome. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.09.003. pii: S1064-7481(13)00350-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weimer K, Gulewitsch MD, Schlarb AA, Schwille-Kiuntke J, Klosterhalfen S, Enck P. Placebo effects in children: a review. Pediatr Res. 2013;74:96–102. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fadai T. Placebo analgesia in children compared to adults Poster. presented at the IASP Congress; Milan, Italy. August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cherniack EP. Would the elderly be better off if they were given more placebos? Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2010;10:131–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2009.00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bingel U, Colloca L, Vase L. Mechanisms and clinical implications of the placebo effect: is there a potential for the elderly? A mini-review Gerontology. 2011;57:354–363. doi: 10.1159/000322090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunz M, Rainville P, Lautenbacher S. Operant conditioning of facial displays of pain. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:422–431. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318218db3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burneo JG, Montori VM, Faught E. Magnitude of the placebo effect in randomized trials of antiepileptic agents. Epilepsy Behav. 2002;3:532–534. doi: 10.1016/s1525-5050(02)00531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rheims S, Cucherat M, Arzimanoglou A, Ryvlin P. Greater response to placebo in children than in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis in drug-resistant partial epilepsy. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt D, Beyenburg S, D'Souza J, Stavem K. Clinical features associated with placebo response in refractory focal epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;27:393–398. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fulda S, Wetter TC. Where dopamine meets opioids: a meta-analysis of the placebo effect in restless legs syndrome treatment studies. Brain. 2008;131:902–917. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ondo WG, Hossain MM, Gordon MF, Reess J. Predictors of placebo response in restless legs syndrome studies. Neurology. 2013;81:193–194. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829a33bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goetz CG, Leurgans S, Raman R, Stebbins GT. Objective changes in motor function during placebo treatment in PD. Neurology. 2000;54:710–714. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.3.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goetz CG, Laska E, Hicking C, Damier P, Müller T, Nutt J, Warren Olanow C, Rascol O, Russ H. Placebo influences on dyskinesia in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23:700–707. doi: 10.1002/mds.21897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goetz CG, Wuu J, McDermott MP, Adler CH, Fahn S, Freed CR, Hauser RA, Olanow WC, Shoulson I, Tandon PK, Parkinson Study Group. Leurgans S. Placebo response in Parkinson's disease: comparisons among 11 trials covering medical and surgical interventions. Mov Disord. 2008;23:690–699. doi: 10.1002/mds.21894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ondo WG. Placebo response in Parkinson trials using patient diaries: sites do matter. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2007;30:301–304. doi: 10.1097/wnf.0b013e31805448d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diener HC, Dowson AJ, Ferrari M, Nappi G, Tfelt-Hansen P. Unbalanced randomization influences placebo response: scientific versus ethical issues around the use of placebo in migraine trials. Cephalalgia. 1999;19:699–700. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1999.019008699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macedo A, Farré M, Baños JE. A meta-analysis of the placebo response in acute migraine and how this response may be influenced by some of the characteristics of clinical trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:161–172. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macedo A, Baños JE, Farré M. Placebo response in the prophylaxis of migraine: a meta-analysis. Eur J Pain. 2008;12:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho TW, Fan X, Rodgers A, Lines CR, Winner P, Shapiro RE. Age effects on placebo response rates in clinical trials of acute agents for migraine: pooled analysis of rizatriptan trials in adults. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:711–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun H, Bastings E, Temeck J, Smith PB, Men A, Tandon V, Murphy D, Rodriguez W. Migraine therapeutics in adolescents: a systematic analysis and historic perspectives of triptan trials in adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:243–249. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meissner K, Fässler M, Rücker G, Kleijnen J, Hróbjartsson A, Schneider A, Antes G, Linde K. Differential effectiveness of placebo treatments: a systematic review of migraine prophylaxis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1941–1951. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Averbuch M, Katzper M. Gender and the placebo analgesic effect in acute pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;70:287–291. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.118366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quessy SN, Rowbotham MC. Placebo response in neuropathic pain trials. Pain. 2008;138:479–483. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamper SJ, Machado LA, Herbert RD, Maher CG, McAuley JH. Trial methodology and patient characteristics did not influence the size of placebo effects on pain. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang W, Robertson J, Jones AC, Dieppe PA, Doherty M. The placebo effect and its determinants in osteoarthritis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1716–1723. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.092015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Häuser W, Bartram-Wunn E, Bartram C, Reinecke H, Tölle T. Systematic review: Placebo response in drug trials of fibromyalgia syndrome and painful peripheral diabetic neuropathy-magnitude and patient-related predictors. Pain. 2011;152:1709–1717. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Capurso G, Cocomello L, Benedetto U, Cammà C, Delle Fave G. Meta-analysis: the placebo rate of abdominal pain remission in clinical trials of chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2012;41:1125–1131. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318249ce93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woods SW, Gueorguieva RV, Baker CB, Makuch RW. Control group bias in randomized atypical antipsychotic medication trials for schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:961–970. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kemp AS, Schooler NR, Kalali AH, Alphs L, Anand R, Awad G, Davidson M, Dubé S, Ereshefsky L, Gharabawi G, Leon AC, Lepine JP, Potkin SG, Vermeulen A. What is causing the reduced drug placebo difference in recent schizophrenia clinical trials and what can be done about it? Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:504–509. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mallinckrodt CH, Zhang L, Prucka WR, Millen BA. Signal detection and placebo response in schizophrenia: parallels with depression. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2010;43:53–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen YF, Wang SJ, Khin NA, Hung HM, Laughren TP. Trial design issues and treatment effect modeling in multi-regional schizophrenia trials. Pharm Stat. 2010;9:217–29. doi: 10.1002/pst.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Potkin S, Agid O, Siu C, Watsky E, Vanderburg D, Remington G. Placebo response trajectories in short-term and long-term antipsychotic trials in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2011;132:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agid O, Siu CO, Potkin SG, Kapur S, Watsky E, Vanderburg D, Zipursky RB, Remington G. Meta-regression analysis of placebo response in antipsychotic trials, 1970-2010. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1335–1344. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12030315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.King BH, Dukes K, Donnelly CL, Sikich L, McCracken JT, Scahill L, Hollander E, Bregman JD, Anagnostou E, Robinson F, Sullivan L, Hirtz D. Baseline factors predicting placebo response to treatment in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: a multisite randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:1045–1052. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sysko R, Walsh BT. A systematic review of placebo response in studies of bipolar mania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1213–1217. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yildiz A, Vieta E, Tohen M, Baldessarini RJ. Factors modifying drug and placebo responses in randomized trials for bipolar mania. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14:863–875. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710001641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen D, Consoli A, Bodeau N, Purper-Ouakil D, Deniau E, Guile JM, Donnelly C. Predictors of placebo response in randomized controlled trials of psychotropic drugs for children and adolescents with internalizing disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20:39–47. doi: 10.1089/cap.2009.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Newcorn JH, Sutton VK, Zhang S, Wilens T, Kratochvil C, Emslie GJ, D'souza DN, Schuh LM, Allen AJ. Characteristics of placebo responders in pediatric clinical trials of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child AdolescPsychiatry. 2009;48:1165–1172. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181bc730d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waxmonsky JG, Waschbusch DA, Glatt SJ, Faraone SV. Prediction of placebo response in 2 clinical trials of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate for the treatment of ADHD. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:1366–1375. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m05979pur. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buitelaar JK, Sobanski E, Stieglitz RD, Dejonckheere J, Waechter S, Schäuble B. Predictors of placebo response in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: data from 2 randomized trials of osmotic-release oral system methylphenidate. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:1097–1102. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blom TJ, Mingione CJ, Guerdjikova AI, Keck PE, Jr, Welge JA, McElroy SL. Placebo response in binge eating disorder: a pooled analysis of 10 clinical trials from one research group. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2014;22:140–146. doi: 10.1002/erv.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Greene NM, Taylor EM, Gage SH, Munafò MR. Industry funding and placebo quit rate in clinical trials of nicotine replacement therapy: a commentary on Etter et al. (2007) Addiction. 2010;105:2217–2218. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Litten RZ, Castle IJ, Falk D, Ryan M, Fertig J, Chen CM, Yi HY. The placebo effect in clinical trials for alcohol dependence: an exploratory analysis of 51 naltrexone and acamprosate studies. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:2128–2137. doi: 10.1111/acer.12197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moore RA, Aubin HJ. Do placebo response rates from cessation trials inform on strength of addictions? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9:192–211. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9010192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brown WA, Johnson MF, Chen MG. Clinical features of depressed patients who do and do not improve with placebo. Psychiatry Res. 1992;41:203–214. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90002-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walsh BT, Seidman SN, Sysko R, Gould M. Placebo response in studies of major depression: variable, substantial, and growing. JAMA. 2002;287:1840–1847. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.14.1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khan A, Leventhal RM, Khan SR, Brown WA. Severity of depression and response to antidepressants and placebo: an analysis of the Food and Drug Administration database. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22:40–45. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Evans KR, Sills T, Wunderlich GR, McDonald HP. Worsening of depressive symptoms prior to randomization in clinical trials: a possible screen for placebo responders? J Psychiatr Res. 2004;38:437–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stein DJ, Baldwin DS, Dolberg OT, Despiegel N, Bandelow B. Which factors predict placebo response in anxiety disorders and major depression? An analysis of placebo-controlled studies of escitalopram. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1741–1746. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo-Medina TB, Scoboria A, Moore TJ, Johnson BT. Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: a meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e45. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Papakostas GI, Fava M. Does the probability of receiving placebo influence clinical trial outcome? A meta-regression of double-blind, randomized clinicaltrials in MDD. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bridge JA, Birmaher B, Iyengar S, Barbe RP, Brent DA. Placebo response in randomized controlled trials of antidepressants for pediatric major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:42–49. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08020247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brunoni AR, Lopes M, Kaptchuk TJ, Fregni F. Placebo response of non-pharmacological and pharmacological trials in major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sinyor M, Levitt AJ, Cheung AH, Schaffer A, Kiss A, Dowlati Y, Lanctôt KL. Does inclusion of a placebo arm influence response to active antidepressant treatment in randomized controlled trials? Results from pooled and meta-analyses. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:270–279. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08r04516blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hunter AM, Cook IA, Leuchter AF. Impact of antidepressant treatment history on clinical outcomes in placebo and medication treatment of major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30:748–751. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181faa474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rutherford BR, Sneed JR, Tandler JM, Rindskopf D, Peterson BS, Roose SP. Deconstructing pediatric depression trials: an analysis of the effects of expectancy and therapeutic contact. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:782–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gueorguieva R, Mallinckrodt C, Krystal JH. Trajectories of depression severity in clinical trials of duloxetine: insights into antidepressant and placebo responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:1227–1237. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Khin NA, Chen YF, Yang Y, Yang P, Laughren TP. Exploratory analyses of efficacy data from major depressive disorder trials submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration in support of new drug applications. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:464–472. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mancini M, Wade AG, Perugi G, Lenox-Smith A, Schacht A. Impact of patient selection and study characteristics on signal detection in placebo-controlled trials with antidepressants. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;51:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ilnyckyj A, Shanahan F, Anton PA, Cheang M, Bernstein CN. Quantification of the placebo response in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1854–1858. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9178676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Su C, Lichtenstein GR, Krok K, Brensinger CM, Lewis JD. A meta-analysis of the placebo rates of remission and response in clinical trials of active Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1257–1269. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Renna S, Cammà C, Modesto I, Cabibbo G, Scimeca D, Civitavecchia G, Mocciaro F, Orlando A, Enea M, Cottone M. Meta-analysis of the placebo rates of clinical relapse and severe endoscopic recurrence in postoperative Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1500–1509. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pitz M, Cheang M, Bernstein CN. Defining the predictors of the placebo response in irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:237–247. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00626-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Patel SM, Stason WB, Legedza A, Ock SM, Kaptchuk TJ, Conboy L, Canenguez K, Park JK, Kelly E, Jacobson E, Kerr CE, Lembo AJ. The placebo effect in irritable bowel syndrome trials: a meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:332–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dorn SD, Kaptchuk TJ, Park JB, Nguyen LT, Canenguez K, Nam BH, Woods KB, Conboy LA, Stason WB, Lembo AJ. A meta-analysis of the placebo response in complementary and alternative medicine trials of irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:630–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ford AC, Moayyedi P. Meta-analysis: factors affecting placebo response rate in the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:144–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Talley NJ, Locke GR, Lahr BD, Zinsmeister AR, Cohard-Radice M, D'Elia TV, Tack J, Earnest DL. Predictors of the placebo response in functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:923–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Enck P, Vinson B, Malfertheiner P, Zipfel S, Klosterhalfen S. The placebo response in functional dyspepsia--reanalysis of trial data. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:370–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.de Craen AJ, Moerman DE, Heisterkamp SH, Tytgat GN, Tijssen JG, Kleijnen J. Placebo effect in the treatment of duodenal ulcer. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;48:853–860. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00094.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yuan YH, Wang C, Yuan Y, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis: incidence of endoscopic gastric and duodenal ulcers in placebo arms of randomized placebo-controlled NSAID trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:197–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cremonini F, Ziogas DC, Chang HY, Kokkotou E, Kelley JM, Conboy L, Kaptchuk TJ, Lembo AJ. Meta-analysis: the effects of placebo treatment on gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:29–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lee S, Malhotra B, Creanga D, Carlsson M, Glue P. A meta-analysis of the placebo response in antimuscarinic drug trials for overactive bladder. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thijs L, Amery A, Birkenhäger W, Bulpitt CJ, Clement D, de Leeuw P, De Schaepdryver A, Dollery C, Forette F, Henry JF, et al. Age-related effects of placebo and active treatment in patients beyond the age of 60 years: the need for a proper control group. J Hypertens. 1990;8:997–1002. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199011000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cho HJ, Hotopf M, Wessely S. The placebo response in the treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:301–313. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000156969.76986.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Freeman EW, Rickels K. Characteristics of placebo responses in medical treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1403–1408. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lamel SA, Myer KA, Younes N, Zhou JA, Maibach H, Maibach HI. Placebo response in relation to clinical trial design: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials for determining biologic efficacy in psoriasis treatment. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012;304:707–717. doi: 10.1007/s00403-012-1266-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Narkus A, Lehnigk U, Haefner D, Klinger R, Pfaar O, Worm M. The placebo effect in allergen-specific immunotherapy trials. Clin Transl Allergy. 2013;3:42. doi: 10.1186/2045-7022-3-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kemeny ME, Rosenwasser LJ, Panettieri RA, Rose RM, Berg-Smith SM, Kline JN. Placebo response in asthma: a robust and objective phenomenon. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1375–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang X, Shang D, Ribbing J, Ren Y, Deng C, Zhou T, Guo F, Lu W. Placebo effect model in asthma clinical studies: longitudinal meta-analysis of forced expiratory volume in 1 second. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:1157–1166. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1245-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McCall WV, D'Agostino R, Jr, Dunn A. A meta-analysis of sleep changes associated with placebo in hypnotic clinical trials. Sleep Med. 2003;4:57–62. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(02)00242-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.McCall WV, D'Agostino R, Jr, Rosenquist PB, Kimball J, Boggs N, Lasater B, Blocker J. Dissection of the factors driving the placebo effect in hypnotic treatment of depressed insomniacs. Sleep Med. 2011;12:557–564. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tudur Smith C, Dwan K, Altman DG, Clarke M, Riley R, Williamson PR. Sharing individual participant data from clinical trials: an opinion survey regarding the establishment of a central repository. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97886. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Krogsbøll LT, Hróbjartsson A, Gøtzsche PC. Spontaneous improvement in randomised clinical trials: meta-analysis of three-armed trials comparing no treatment, placebo and active intervention. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hofstra WB, Sterk PJ, Neijens HJ, Kouwenberg JM, Duiverman EJ. Prolonged recovery from exercise-induced asthma with increasing age in childhood. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1995;20:177–183. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950200309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Furukawa TA, Noma H, Caldwell DM, Honyashiki M, Shinohara K, Imai H, Chen P, Hunot V, Churchill R. Waiting list may be a nocebo condition in psychotherapy trials: a contribution from network meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014 doi: 10.1111/acps.12275. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rutherford BR, Mori S, Sneed JR, Pimontel MA, Roose SP. Contribution of spontaneous improvement to placebo response in depression: a meta-analytic review. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:697–702. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Posternak MA, Miller I. Untreated short-term course of major depression: a meta-analysis of outcomes from studies using wait-list control groups. J Affect Disord. 2001;66:139–146. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hróbjartsson A, Gøtzsche PC. Placebo interventions for all clinical conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD003974. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003974.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Meissner K. Preferring patient-reported to observer-reported outcomes substantially influences the results of the updated systematic review on placebos by Hróbjartsson and Gøtzsche. J Intern Med. 2005;257:394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kobak KA, Kane JM, Thase ME, Nierenberg AA. Why do clinical trials fail? The problem of measurement error in clinical trials: time to test new paradigms? J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:1–5. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31802eb4b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rief W, Nestoriuc Y, Weiss S, Welzel E, Barsky AJ, Hofmann SG. Meta-analysis of the placebo response in antidepressant trials. J Affect Disord. 2009;118:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kirsch I. The Emperor's New Drugs: Medication and placebo in the treatment of depression. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-44519-8_16. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Grelotti DJ, Kaptchuk TJ. Placebo by proxy. BMJ. 2011;343:d4345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lidstone SC, Schulzer M, Dinelle K, Mak E, Sossi V, Ruth TJ, de la Fuente-Fernandez R, Phillips AG, Stoessl J. Effects of expectation on placebo-induced dopamine release in Parkinson Disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:857–865. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lou JS, Dimitrova DM, Hammerschlag R, Nutt J, Hunt EA, Eaton RW, Johnson SC, Davis MD, Arnold GC, Andrea SB, Oken BS. Effect of expectancy and personality on cortical excitability in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2013;28:1257–1262. doi: 10.1002/mds.25471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A, Maric K, Tendal B. Data extraction errors in meta-analyses that use standardized mean differences. JAMA. 2007;29:430–437. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.4.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]