Abstract

Introduction

Few studies have evaluated interventions to improve quality of life (QOL) for Latina breast cancer survivors and caregivers. Following best practices in community-based participatory research (CBPR), we established a multi-level partnership among Latina survivors, caregivers, community-based organizations (CBOs), clinicians and researchers to evaluate a survivor-caregiver QOL intervention.

Methods

A CBO in the mid-Atlantic region, Nueva Vida, developed a patient-caregiver program called Cuidando a mis Cuidadores (Caring for My Caregivers), to improve outcomes important to Latina cancer survivors and their families. Together with an academic partner, Nueva Vida and 3 CBOs established a multi-level team of researchers, clinicians, Latina cancer survivors, and caregivers to conduct a national randomized trial to compare the patient-caregiver program to usual care.

Results

Incorporating team feedback and programmatic considerations, we adapted the prior patient-caregiver program into an 8-session patient- and caregiver-centered intervention that includes skill-building workshops such as managing stress, communication, self-care, social well-being, and impact of cancer on sexual intimacy. We will measure QOL domains with the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), dyadic communication between the survivor and caregiver, and survivors’ adherence to recommended cancer care. To integrate the intervention within each CBO, we conducted interactive training on the protection of human subjects, qualitative interviewing, and intervention delivery.

Conclusion

The development and engagement process for our QOL intervention study is innovative because it is both informed by and directly impacts underserved Latina survivors and caregivers. The CBPR-based process demonstrates successful multi-level patient engagement through collaboration among researchers, clinicians, community partners, survivors and caregivers.

Keywords: Quality of Life, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research, Community-Based Participatory Research, Latinos, Breast Cancer, Intervention Studies

Introduction

In the United States, 50.5 million people are of Hispanic/Latino origin [1]. Among them, the lifetime risk for cancer is striking: 1 in 2 for men and 1 in 3 for women [2]. With growing numbers of Latinas surviving breast cancer [3,4], attention to quality of life (QOL) issues in this population has also increased [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

Latina breast cancer survivors have lower QOL compared to non-Latinas [6,8,14,15]. The disparity in QOL experienced by Latinas appears to be clinically significant in terms of distress due to strained spousal and family relationships, poorer physical functioning, depression, pain, and fatigue [16,17,18]. Latina survivors also have lower rates of returning to work [19,20]. Finally, psychological well-being between Latina survivors and their caregivers is interdependent [21].

Cancer caregivers experience increased distress [22] and physical symptoms [22,23,24] compared to age- and gender-matched controls [25]. Moreover, physical health outcomes of breast cancer patient caregivers are related to the patients’ depression and stress [26]. The few studies that have explored Latino caregivers’ unique needs and outcomes indicate communication difficulties and caregivers’ lack of confidence in coping with the survivors’ illness or distress [27,28,29].

Quality of Life Support Services and Interventions with Latina Survivors and Families

A few studies have evaluated QOL interventions in Latina and Hispanic breast cancer survivors [7,9,10,11,13], with mixed results. The level of patient-engagement in the design and implementation of the interventions varied, with some studies demonstrating successful methods of engaging Latina survivors [10,13]. Likewise, few studies have examined interventions that involve both Latina survivors and their caregivers [27,30]. One survivor-caregiver intervention led to improvements in QOL for Mexican-American survivors and caregivers [27]. To our knowledge, no other QOL interventions to date have included Latinos from countries beyond Mexico or engaged survivors and caregivers in the development and implementation of a QOL intervention evaluated in a randomized controlled trial (RCT).

The purpose of this paper is to describe a multi-level partnership to implement a QOL intervention for a diverse sample of Latina breast cancer survivors and their caregivers. We highlight the significant multi-level collaboration between patients, caregivers, community-based organizations (CBOs), clinicians and academic researchers. We also address cultural factors specific to Latino engagement with and participation in QOL research and practical tips for multi-level research teams when conducting a RCT.

Methods

Initial Development of the Nueva Vida QOL Intervention: A Model for Involving Patients as Research Agents and Participants

Nueva Vida, a CBO in the Washington, DC metropolitan area that serves Latina breast cancer survivors and their families, adapted an award-winning program originally developed to support Latino families after September 11, 2001 [31]. The program was adapted to address the needs of and incorporate feedback from Latina breast cancer survivors and their families. The foundation for the current RCT, the Caring for my Caregivers/Cuidando a mis Cuidadores program, was co-developed by a Latina mental health professional and breast cancer survivor who was one of the founders of Nueva Vida (MGE). The Cuidando a mis Cuidadores program was thus developed with patient agency and an understanding of Latino values. The original program incorporated principles from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy [32] and clinical expertise on caregivers’ needs [33]. The program included group-based skill-building workshops in which Latina survivors and their caregivers were part of concurrently-held but separate groups (survivors in one room; caregivers in another). This separation met the needs of Latino participants by encouraging them to freely share their experiences and feelings without worrying about upsetting the other person. Through the use of community-based participatory research (CBPR) principles [34] and following guidelines for patient-engagement in research [35] the program has evolved over 5 years into an 8-session psycho-educational QOL intervention for use with Latina breast cancer survivors and their caregivers. We will evaluate the program, now called the Nueva Vida Intervention, within a multi-site RCT [36,37].

Development of Organizational Culture that Encourages Research with Patients

One key element of engaging patients in research is collaboration with CBOs or other agencies that provide services to the patient population of interest, as these organizations are well-positioned to develop a culture that fosters patients’ awareness of and engagement in research. For example, in addition to documented barriers to Latinos’ participation in research such as stigma, lack of accessibility, language, and time constraints [38,39], Nueva Vida observed other reasons for Latinos’ lower research participation, including clients’ negative former experiences with research, the lack of culturally appropriate protocols, and poor dissemination of information back to patients.

To overcome these barriers and encourage participation in the original Cuidando a mis Cuidadores program, Nueva Vida talked with Latino clients about the importance of evaluation to improve services. Participation was also presented as an opportunity to be part of developing solutions to problems encountered after a cancer diagnosis and treatment. Helping patients and their family members feel invested in the process fostered participation in the original evaluation of the program.

Establishing a Multi-Level, Patient-Centered Research Team

Due to strong participation and positive feedback, Nueva Vida partnered with Georgetown University to formally evaluate the Cuidando a mis Cuidadores program in a larger RCT. This community-academic partnership between Nueva Vida and Georgetown expanded to include three other CBOs that provide services to Latino cancer survivors and their families. Key to the participation of CBOs from across the nation was Nueva Vida’s existing connection to a network of organizations providing services to Latinas with cancer. Nueva Vida introduced Georgetown to these other CBOs, and Georgetown served as the hub through which these CBOs and other patient-, caregiver- and patient-advocate partners could provide input on the design and outcomes of the QOL RCT. We expanded the team to include other patient and caregiver partners identified through recommendations from the CBOs. We retained these partners during the study planning process through use of phone calls and emails.

Following a framework that guides implementation and evaluation of interventions in communities that often experience health disparities [13,40,41], we outline the research development process as a series of methodological phases. Of note, these phases also map onto the principles of CBPR [34] and guidelines for patient engagement from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute [35].

Phase I: Establish Patient-Centered Infrastructure for the Project, Timeline: 5 months

Select Partners with Demonstrated Commitment to Patient Outcomes

The project includes four CBO Site Principal Investigators (PIs; two are Latina cancer survivors, one is a Latina mental health professional) and an academic PI. The four CBOs involved in this research offer first-hand knowledge and culture-specific expertise about and access to patient and caregiver participants, and connections to key constituents for results dissemination. The following sections provide a brief description of each CBO and other study partners (Consultants, Advisory Board Members).

Gilda’s Club New York City, NY (GCNYC) [42]

GCNYC opened their doors in June 1995 to create a welcoming and supportive community for anyone affected by cancer. GCNYC’s free program has offered support and networking groups, educational lectures, workshops and social events to over 7,300 members, and has existing programs for Latinos. Among GCNYC’s clients, 13% are Latino.

Latinas Contra Cancer, San Jose, CA (LCC) [43]

LCC was founded in 2003 by Latina cancer survivor Ysabel Duron to serve primarily low-income, immigrant (34%) and Spanish speaking Latinos, most of whom are from Mexico (approximately 95%). LCC aims to diminish the fear surrounding the word “cancer” in the Latino community and increase understanding about prevention, screening and treatment.

Nueva Vida, Inc., Washington, DC [44]

Nueva Vida developed the original patient-caregiver program that was adapted into the present QOL intervention. Its mission is to inform, support, and empower Latinas whose lives are affected by cancer, and to advocate for and facilitate timely access to state-of-the-art care. The majority of the Latinas served at Nueva Vida are from Central American countries other than Mexico (55%), South America (19%), and Mexico (18%).

Self-Help for Women with Breast or Ovarian Cancer, New York City, New York (SHARE) [45]

SHARE is a group of breast and ovarian cancer survivors and their caregivers, friends and families, founded in 1976. LatinaSHARE was started in late 1994 to provide support, information, education and advocacy opportunities for the Latino community. The majority of the Latinos served by SHARE are from the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Ecuador, or Mexico.

Advisory Board

Our five advisory board members provide expert input on execution of the study. These individuals include one Latina and one African American breast cancer survivor, a medical oncologist, an oncology surgeon and a Latino caregiver. They are included on team communications and invited to attend conference calls and annual team meetings to provide input to the academic and site PIs.

Consultants

Consultants provide content expertise for the intervention, and include a clinician with expertise in caregiving [33], a bilingual-bicultural Mexican-American cancer disparities researcher (AN), one of the founders of Nueva Vida and co-developer of the original Cuidando a mis Cuidadores program (MGE), and an established researcher with expertise in community outreach and engagement.

Phase 2: Identify Patient-Centered Inputs for Intervention, Timeline: 2 months

Cultural Considerations for Patient Engagement

The Nueva Vida intervention reflects the Latino values personalismo and familismo and avoids stigma that is commonly associated with mental health care among the Latino community [12,38,46,47,48]. Personalismo, the expectation to develop warm relationships, extends to medical and mental health care within the Latino community. The intervention sessions include a shared meal and will allow for the development of genuine relationships with other participants and study interventionists. Familismo, the social valuing of the family unit over individual interests, is reflected by the focus on both the survivor and her caregiver, with recognition that a cancer diagnosis impacts everyone in the family. Finally, to circumvent potential stigma associated with attendance, the intervention is promoted as a workshop instead of a support group. Although our intervention focuses on improving quality of life, Latinos may misconstrue a support group as mental health services and stigma has been associated previously with lower utilization rates of mental health services among Latinos [48].

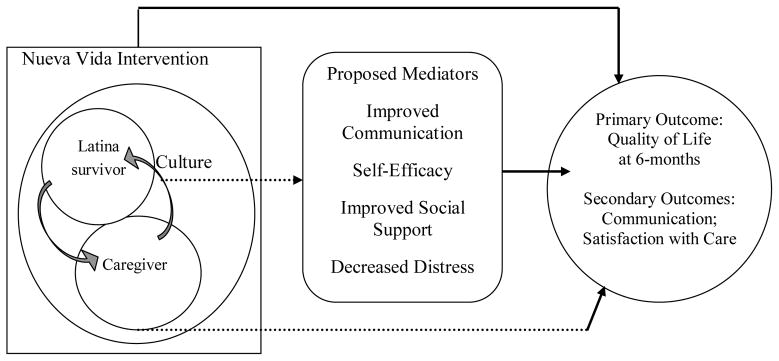

Conceptual Considerations in Patient Engagement

Guided by Latino cultural values and a focus on patient and caregiver engagement, our intervention is influenced by the Contextual Model of Health-Related QOL [5], Social Cognitive Theory [49] and dyadic relationships between the survivor and caregiver [50]. The Contextual Model of Health-Related QOL specifies individual, cultural, and contextual influences (dyadic relationships, communication with physicians) as important determinants of QOL. Patient and caregiver partners identified communication skills as important to QOL. One of our advisory board members, a caregiver, completed a qualitative interview regarding the potential intervention session topics, and also reviewed the interventionist manual. At yearly in-person meetings and monthly conference calls, community partners with direct experience as caregivers or providing services to Latino caregivers and care recipients, participated in brainstorming about intervention components. Drawing from Social Cognitive theory, the intervention is designed to increase self-efficacy, or confidence, in communication (with their survivor/caregiver and healthcare providers).

Phase 3: Integrate and Adapt Intervention, Study Design and Outcomes, Timeline: 8 months

During study planning, team discussions addressed practical considerations of the intervention’s frequency, length, and participant eligibility. As a result, the intervention was reduced from 14 sessions to 8, frequency was increased to twice a month, and participant eligibility was broadened to include any Latina breast cancer survivors between the ages of 18–80, regardless of the time since diagnosis.

Developing Assessment of Patient-Reported Outcomes

Based on the conceptual model and outcomes identified as important to our patient-, caregiver- and CBO-partners, we identified specific constructs as independent and dependent variables. Staff members at Nueva Vida, including the co-founder of the intervention, a breast cancer survivor (MGE), provided input on assessment of country of origin, self-efficacy, and communication and emphasized the need for careful review of the cultural appropriateness and use of language in these assessments. The CBO collaborators provided input on assessment variables during the drafting of the grant proposal and the initial team meeting. Collaborators also reviewed drafts of the assessment measures and provided input on assessment time points. We then engaged two Latina survivors and one CBO staff member from different countries of origin in practice assessment interviews and elicited feedback for improvement of the question wording and language choice.

Based on this input and a review of the literature and study objectives, we developed a survey to assess medical history and status, acculturation, social support, distress, sexual functioning, medical trust and satisfaction, coping, interpersonal functioning, familism, communication, demographics, QOL (primary outcome), and satisfaction with and adherence to cancer surveillance care (secondary outcomes). Site PIs provided input to ensure assessment of important patient-reported outcomes. Using REDCap survey software, we will administer the survey over the telephone in English or Spanish to eliminate language barriers.

We selected validated self-reported measures (in English and Spanish) to address each construct (Table 1). The primary QOL outcomes are measured using PROMIS® 8-item short forms for the following domains: physical function, satisfaction with social roles and activities, depression, anxiety, and anger [51,52,53,54]. PROMIS measures generate t-scores standardized to the U.S. population. PROMIS follows a strict translation protocol for cross-cultural and language translation [55]. PROMIS measures have been shown to be reliable and valid across both the general population and in patients with chronic illnesses [52,53,54].

Table 1.

Variables, Measures, and Assessment Time Points for Study Participants

| Variables | Measures | T0 | T1 | T2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acculturation [59] | Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics | X | ||

| Physical Function [60] | PROMIS SF v1.2 – Physical Function – Short Form 6b | X | X | X |

| Anxiety [60] | PROMIS Item Bank v1.0 – Emotional Distress – Anxiety – Short Form 6a | X | X | X |

| Depression [60] | PROMIS Item Bank v1.0: Emotional Distress – Depression – Short Form 6a | X | X | X |

| Fatigue [60] | PROMIS Item Bank v1.0: Fatigue – Short Form 4a | X | X | X |

| Satisfaction with | PROMIS Item Bank v1.0 – Satisfaction with | X | X | X |

| participation in social roles [60] | Participation in Social Roles – Short Form 6a | |||

| Sexual functioning in women [61] | Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) | Xsp | Xsp | Xsp |

| Body image [62] | Body Image after Breast Cancer Questionnaire (BIBCQ) | Xs | Xs | Xs |

| Experience with follow-up care doctor communication [63] | Experience of Care and Health Outcomes of Survivors and Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (ECHOS-NHL) Survey Instrument, Overall Communication Section | Xs | Xs | Xs |

| Functional social support [64] | Duke-University of North Carolina Functional Social Support Questionnaire (DUFSS) | X | X | X |

| Response to cancer diagnosis [65] | Impact of Event Scale | X | ||

| Medical mistrust, suspicion subscale [66] | Suspicion Subscale from Group-Based Medical Mistrust Scale | X | X | X |

| Patient satisfaction [67] | Short- Form Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18) | X | X | X |

| Religious coping [68] | Spanish Brief Religious Coping Scale (S-BRCS) | X | X | X |

| Dyadic communication [69] | Mutuality and Interpersonal Sensitivity Scale (MIS) | X | X | X |

| Self-efficacy for coping with cancer [70] | Cancer Behavior Inventory-Brief (CBI-B) | Xs | Xs | Xs |

| Caregiver efficacy [71] | Caregiver Inventory | Xc | Xc | Xc |

Note: T0 = pre-intervention baseline assessment, T1 = post-intervention assessment, T2 = 6-month follow-up assessment, Xs = administered only to survivor, Xc = administered only to caregiver, Xsp = administered only to survivors and caregivers who indicated they are partners

Balancing Research Structure and Site Flexibility: Engaged Intervention Topic Selection

At an initial team meeting with patients, community, and academic partners, we discussed the need to promote consistency in intervention delivery yet allow flexibility for the workshop topics to meet participants’ needs at each community site. Together we decided to select five of the eight intervention workshop topics as “core” topics and have RCT participants select three topics based on their unique needs (see Table 2). The entire study team was invited to vote on the core topics. This democratic, collaborative process is reflective of CBPR principles [34]. The resulting core topics were: 1) Introduction and The Impact of Cancer on the Family, 2) Improving Communication: Family, Friends, and Health Care Providers, 3) Stress Management, 4) Balancing Emotional and Physical Needs, and 5) Spirituality and Cancer.

Table 2.

Nueva Vida Intervention Workshop Topics

| Workshop Topics |

|---|

| The Impact of Cancer on the Family (Introduction Session)* |

| Stress Management* |

| Anger Management |

| Improving Communication: Family, Friends, and Providers* |

| Intimacy after Cancer: Emotional and Sexual |

| Spirituality and Cancer* |

| Balancing Emotional and Physical Needs* |

| Trauma and Cancer |

| Role Changes |

| Understanding Distress |

| Myths and Cancer |

| Including Others in Helping Caregivers |

| Putting Our Lives in Order |

Note: Each intervention group will select 3 topics of interest and will share 5 core topics (denoted with an asterisk).

Phase 4: Build Community Capacity for Research and Intervention Delivery, Timeline for startup: 1 year, maintenance: ongoing

Select and Train Staff

Human Subjects Research Training for CBOs

CBOs and the academic partner were individually responsible for identifying and hiring (when needed) qualified staff to support study implementation. Once staff were selected, we identified an interactive human subjects research training curriculum developed for the CBO audience called CIRTification: Community Involvement in Research Training [56]. CIRTification provides facilitator and trainee materials that review key human subjects’ research concepts and activities specific to research in community settings. Materials are written in lay language, take into account CBOs’ limited experience with research, and provide examples relevant to the patient- and community-engaged context. In addition, we developed a complementary HIPAA training to address topics specific to conducting research with a medical population, such as breast cancer survivors. We used state-of-the-art translation approaches to translate the materials into Spanish. According to guidelines recommended by the U.S. Census Bureau, a well-translated survey instrument should have semantic equivalence (words and sentence structure express the same meaning) across languages, conceptual equivalence (concept being measured is the same) across cultures, and normative equivalence (address social norms that may differ across cultures) [57]. Per the literature, target population, message, purpose, timing, location, and method of delivery were taken into account during the translation process. Bilingual native Spanish speakers translated materials. Other native speakers from our CBO partners were invited to crosscheck documents for accurate translation. Team reconciliation discussions were held in which final translations were determined by consensus. Translators were also offered expert guidance on common English to Spanish translation pitfalls such as relying heavily on gerunds, overuse of adverbs and the present continuous tense, using loan translations and overuse of capital letters.

All training materials were reviewed and approved by the Georgetown-MedStar Oncology IRB. The telephone-delivered CIRTification and HIPAA training included study-specific examples and role plays. Partners were empowered to ask targeted questions relevant to the day-to-day activities of the RCT. Trainees were given the option to attend sessions in English (with Spanish interpretation as needed) or entirely in Spanish. We solicited feedback at the end of the training (verbal and written); feedback indicated that trainees appreciated the live, interactive format and the study-specific examples and role plays.

Interventionist Training

The development of the interventionist training manual was a collaborative process, with input from Site PIs, site study staff and clinical and academic team members. We adapted the original program manual (written by MGE) and finalized English and Spanish translations (see Table 2). The training was attended by the CBO interventionists (several of whom are Latina breast cancer survivors), researchers, and two consultants. The training included sharing individual goals, study goals, the history of the intervention, an imagery exercise to elicit the caregiver perspective, group facilitation strategies and topic-focused role plays.

Assemble and Translate Study Materials

Bilingual team members translated materials from English to Spanish. Patient, community and academic team members collaborated to ensure materials were worded in a way that would be understood by populations served at each site. Thus translation took into consideration cultural differences among the different Latino groups served by the CBO study partners. For example, one site indicated that the word rabia can be interpreted as “anger” or as “rabies,” depending on one’s country of origin and suggested using another word for anger. Other feedback included suggestions for more direct phrasing, and elimination of phrases that do not translate well (for example, it was suggested that the phrase “as a small thanks” should not be translated literally). Throughout the study sites are encouraged to use the translations as a guide and also to put workshop content in their own words so that it is adapted to each group as needed. Thus concepts may be explained in slightly distinct ways across sites, but intervention components and assessments remain standardized for all participants. Measures were translated and then reviewed by the study partners. Most scales were already available in Spanish and reviewed by the study team’s psychometrician (REJ). The psychometrics of all scales will be evaluated.

Compensate Personnel and CBOs

Georgetown University executed subcontracts with each of the four CBOs. Site PIs manage their individual budgets to fit the needs of their organization. Subcontract compensation began at the start of the project (July 2013) and continues monthly. Consultants are paid hourly and Advisory Board Members receive annual honorariums. Compensation is linked to stakeholder engagement by providing true investment into personnel time and training to prepare for and implement the study trial.

Phase 5: Evaluate the intervention in a randomized trial, Timeline for startup: 1 year, maintenance: ongoing

Aims of the Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT)

We designed our study to evaluate the impact of the Nueva Vida intervention on QOL outcomes for breast cancer survivors and their caregivers compared to usual care with the following aims: Aim 1. Evaluate the impact of the intervention on Latina survivors’ and caregivers’ QOL. Aim 2. Identify mediators of the intervention on QOL (such as communication self-efficacy, social support and distress). Aim 3. Evaluate the impact of the intervention on Latina survivors’ satisfaction with their cancer care. Exploratory Aim: To explore the impact of the intervention on Latina survivors’ adherence to guideline-concurrent care and surveillance. We will conduct study assessments at baseline, immediately post-intervention (within 2 weeks of the last day of the intervention), and 6-months post-intervention.

Establish Enrollment

To facilitate enrollment, eligibility criteria were designed to include as many potential breast cancer survivors and their caregivers as possible. CBOs will tailor recruitment strategies to their individual sites. Our community partners have emphasized the importance of first recruiting the Latina survivors and then asking the survivors to identify appropriate caregivers (vs. direct recruitment of caregivers). Each site will have 6–10 participants in the intervention group and 6–10 in the usual care group for a total of 12–20 participants per round. The expected numbers of intervention rounds at each site are two for Gilda’s Club, two for Latinas Contra Cancer, three for Nueva Vida, Inc. and three for SHARE.

Maximize Retention

Efforts to maximize retention place emphasis on cultivation and maintenance of relationships between CBOs and study participants as well as verifying contact information and troubleshooting any barriers to participation. To maximize retention, child care and a transportation supplement will be provided as needed, along with $10 gift cards or cash for attending workshops and completing assessments. The target sample size is 100 Latina survivor and caregiver dyads (N = 200) retained for the 6-month assessment. Sample size was based on power calculations to meet study aims to evaluate the impact of the intervention on QOL outcomes, identify mediators of the intervention impact on OQL, and evaluate the impact of the intervention on Latina survivors satisfaction with cancer care. With 50 Latina survivors (and caregivers) per arm we will have 84% power to detect clinically significant differences in individual QOL domains of 6 points (0.6 SD) at a significance level of 0.05 [58]. We anticipate that 125 patient-caregiver dyads will participate in the randomized trial (allowing for 20% attrition with a final sample size of 100 dyads). We hope and expect to build strong relationships with our study participants to maximize retention; however, if one member of the dyad decides to no longer participate, the other person in the dyad can still continue with the study. We will first communicate with the participating member of the dyad and then, with permission, reach out to the non-participating member of the dyad through individual telephone calls from the study interventionist to assess reasons for drop-out and encourage a return to the intervention if appropriate.

Quality Assurance Measures

Efforts to ensure intervention fidelity include intermittent interventionist booster trainings, monthly interventionist calls and intervention process questionnaires. A CBO team member suggested conducting exit interviews with intervention study participants after the 8-week program to elicit information not captured with the quantitative surveys. Exit interviews will be conducted within two weeks of the final intervention session. The site PI, site project director, or a study staff member from Georgetown University will conduct these interviews. In these interviews we will use qualitative analysis methods to evaluate participants’ reports of satisfaction, skills they learned, and what they liked and disliked about their experience.

Discussion

We have learned a number of lessons developing and implementing a patient- and community-engaged RCT of a QOL intervention which are described below. For each lesson learned, we have provided the phases and stakeholder groups affected.

Lessons Learned: Developing an Empirical Evaluation of a Patient-Centered CBO Program

1. Relationships lead to partnerships

Phase I, Stakeholders: CBOs, academic partners. Before anything else, a relationship firmly grounded in trust and mutual respect must be established among key stakeholders. Academic researchers can earn trust and respect from CBOs and their patients by asking about and responding to articulated needs. Conversely, CBOs can reap the benefits of incorporating research into their services by being receptive to the research process and acknowledging the value of gathering empirical evidence. Evidence can then be shared with clients, partners, funders, and other key constituents.

2. Be receptive to what is already being done in the community in service of patient populations

Phase 1, Stakeholders: CBOs, academic partners, patients. CBOs offer a wealth of existing patient-centered programs as well as expertise and familiarity with the needs and priorities of target patient populations. Thus, researchers can approach collaborations with CBOs from a service-oriented perspective in which empirical evaluation and academic expertise are offered as a next step in the evolution of CBO patient initiatives. Academic partners could also provide guidance on how to systematically evaluate a program that is implemented across different organizations.

3. Have a plan for addressing questions and conflict

All Phases, All Stakeholders. Proper handling of questions and conflict will strengthen alliances. A team can strike a balance between honoring patient and CBO needs and research objectives by creating an environment that allows for articulating distinct needs and establishing common ground. All parties concerned must exercise flexibility, respect, and transparency about points that are of highest importance to them. Ensure all voices are heard by creating a structure that allows for routine input from all stakeholders at all stages of the study and regularly eliciting questions and concerns.

4. Use a democratic approach to decision-making and project development

Phases 1–3, Stakeholders: CBOs, academic partners, advisory board, consultants, patients, caregivers. A democratic process ensures fairness and is a concrete method for incorporating team member input into the development and execution of the study. For this project, team members were invited to vote on the study logo design, core intervention topics, and provide feedback on study materials such as the consent forms, assessments, recruitment flyers and interventionist manual.

5. Be clear about roles and responsibilities

All Phases, All Stakeholders. Roles and responsibilities were established early on in this study and outlined in a governance plan that was reviewed and approved by study leadership. Having each Site PI serve as part of the leadership team has proven invaluable for training study staff, study refinement, and implementation.

Lessons Learned: Implementation and Logistical Considerations

The large size and geographic dispersion of the multi-level research team has led to identification of logistical and implementation lessons.

1. Communicate regularly with the whole team for consistency and to promote team cohesion

All Phases, Stakeholder: Academic partner. We implemented a process of consolidating important information into regular newsletter-style team emails to inform all concerned of important updates, opportunities, and requests for action. One challenge (and asset) of the current study is that team members are located at various sites across the United States. To foster group cohesion across sites, we hold monthly team calls to share updates, check in on progress, and allow time for questions and concerns. In addition, we created a private Facebook page for team members to share news and accomplishments. Finally, we begin in-person meetings by asking team members to share goals or ideas related to their personal participation on the research team.

2. Ensure study files and procedures are clear, accessible to all collaborators, and HIPAA-compliant

All Phases, Stakeholder: Academic partner. In response to questions that emerged at multiple sites, we developed a document with frequently asked questions (FAQs). Non-confidential study documents are available in a shared online folder. Confidential files with study data or participant contact information are shared through an encrypted file sharing website (Georgetown Box) approved for use by Georgetown University’s IRB. Only study personnel who have completed human subjects’ research and HIPAA training have access to these confidential study files.

3. Be prepared to spend time educating team members about the study process, and review as needed

All Phases, Stakeholder: Academic partner. We created a study process flow chart and discuss research design issues during conference calls to clarify the research process. For example, some study staff were unclear about the study randomization process (e.g., can a participant choose a group?). We provided recruitment scripts to clarify randomization (at the level of the survivor-caregiver dyad) for both study staff and potential participants.

4. Offer training that meets partners’ needs

All Phases, Stakeholder: Academic partner. We offered interactive qualitative interview and human subjects research and HIPAA training developed specifically for a CBO audience. Trainings included slide presentations (shared online and discussed by conference call) to minimize technology complications.

5. Be prepared for a higher administrative burden that coincides with having a large team

All Phases, Stakeholders: CBOs, Academic partner. Multiple sites are ultimately of great benefit in terms of furthering patient-engaged research and dissemination of study outcomes; however it is important to allow more time to handle the volume of IRB and other regulatory documents that need to be gathered, organized, and approved for multiple study staff at each site.

6. Be flexible

All Phases, All Stakeholders. For this study, flexibility enabled successful collaboration with four unique community partners. For example, one site employs mental health professionals to provide support services to Latina survivors while another uses trained survivor peers. We opted to have each site choose the background of the interventionists to best fit sites’ preferences and staff resources.

Conclusion

The development and engagement process for this study is innovative because it is both informed by and directly impacts underserved Latina survivors and their caregivers. The process demonstrates successful multi-level patient engagement through collaboration among survivors, caregivers, clinicians, CBOs and academic researchers. We provide one example of patient-engagement methods in QOL and patient-reported outcomes research by delineating cultural factors in patient engagement, involving patients as agents as well as participants in research, and highlighting patient and community engagement in clinical trials involving patient-reported outcomes.

Fig. 1.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend a special thank you to all of the study team members and participants for their individual contributions to this research. The research is supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI; AD-12-11-5365, Graves) and is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02222337). Funding was also provided in part through NIH/NCI Grant P30-CA051008, Grant # UL1TR000101 (previously UL1RR031975) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (NIH), through the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program (CTSA), a trademark of DHHS, part of the Roadmap Initiative, “Re-Engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise” and the National Institute on Aging Grant 1 P30-AG15272 (Nápoles) and National Cancer Institute Grant U54CA153511 (Nápoles).

Footnotes

Statement of Ethical Conduct This research was approved by the Georgetown University Institutional Review Board and has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. All persons who have participated to date have given their informed consent and any future participants will give their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce. [Accessed 1 May 2014.];The Hispanic Population: 2010. 2010 Census Briefs. Report No. C2010BR-04 issued May 2011. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf.

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for Hispanics/Latinos 2012–2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2012. [Accessed 1 May 2014.]. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-034778.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed 1 October 2014.];Cancer among women. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/data/women.htm.

- 4.National Cancer Institute, Office of Cancer Survivorship. [Accessed 1 October 2014.];Definitions. http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/statistics/definitions.html.

- 5.Ashing-Giwa KT. The contextual model of HRQoL: a paradigm for expanding the HRQoL framework. Quality of Life Research. 2005;14(2):297–307. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-0729-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashing-Giwa KT, Tejero JS, Kim J, Padilla GV, Hellemann G. Examining predictive models of HRQOL in a population-based, multiethnic sample of women with breast carcinoma. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16(3):413–428. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashing K, Rosales M. A telephonic-based trial to reduce depressive symptoms among Latina breast cancer survivors. Psycho-oncology. 2014;23(5):507–515. doi: 10.1002/pon.3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graves KD, Jensen RE, Canar J, Perret-Gentil M, Leventhal KG, Gonzalez F, et al. Through the lens of culture: quality of life among Latina breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2012;136(2):603–613. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2291-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hershman DL, Greenlee H, Awad D, Kalinsky K, Maurer M, Kranwinkel G, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a clinic-based survivorship intervention following adjuvant therapy in breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2013;138(3):795–806. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2486-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juarez G, Mayorga L, Hurria A, Ferrell B. Survivorship education for Latina breast cancer survivors: empowering survivors through education. Psicooncologia (Pozuelo de Alarcon) 2013;10(1):57–68. doi: 10.5209/rev_PSIC.2013.v10.41947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juarez G, Hurria A, Uman G, Ferrell B. Impact of a bilingual education intervention on the quality of life of Latina breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2013;40(1):E50–E60. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.E50-E60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez-Class M, Perret-Gentil M, Kreling B, Caicedo L, Mandelblatt J, Graves KD. Quality of life among immigrant Latina breast cancer survivors: realities of culture and enhancing cancer care. Journal of Cancer Education. 2011;26(4):724–733. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0249-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Napoles AM, Santoyo-Olsson J, Ortiz C, Gregorich S, Lee HE, Duron Y, et al. Randomized controlled trial of Nuevo Amanecer: A peer-delivered stress management intervention for Spanish-speaking Latinas with breast cancer. Clinical Trials (London, England) 2014;11(2):230–238. doi: 10.1177/1740774514521906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janz NK, Mujahid MS, Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Alderman A, Hamilton AS, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in quality of life after diagnosis of breast cancer. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2009;3(4):212–222. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0097-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yanez B, Thompson EH, Stanton AL. Quality of life among Latina breast cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2011;5(2):191–207. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0171-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla GV, Bohorquez DE, Tejero JS, Garcia M. Understanding the breast cancer experience of Latina women. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2006;24(3):19–52. doi: 10.1300/J077v24n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Epstein RM, Street RL., Jr . Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007. [Accessed 1 October 2014.]. NIH Publication No. 07-6225. http://www.outcomes.cancer.gov/areas/pcc/communication/pcc_monograph.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eversley R, Estrin D, Dibble S, Wardlaw L, Pedrosa M, Favila-Penney W. Post-treatment symptoms among ethnic minority breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2005;32(2):250–256. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.250-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blinder V, Patil S, Eberle C, Griggs J, Maly RC. Early predictors of not returning to work in low-income breast cancer survivors: a 5-year longitudinal study. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2013;140(2):407–416. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2625-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blinder VS, Patil S, Thind A, Diamant A, Hudis CA, Basch E, Maly RC. Return to work in low-income Latina and non-Latina white breast cancer survivors: a 3-year longitudinal study. Cancer. 2012;118(6):1664–1674. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Segrin C, Badger TA. Interdependent psychological distress between Latinas with breast cancer and their supportive partners. Journal of Latina/o Psychology. 2013;1(1):21–34. doi: 10.1037/a0030345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Given BA, Sherwood P, Given CW. Support for caregivers of cancer patients: transition after active treatment. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2011;20(10):2015–2021. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Given CW, Given BA. Depression and physical health among family caregivers of geriatric patients with cancer--a longitudinal view. Medical Science Monitor. 2004;10(8):CR447–CR456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, Scanlan JM. Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(6):946–972. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song JI, Shin DW, Choi JY, Kang J, Baik YJ, Mo H, et al. Quality of life and mental health in family caregivers of patients with terminal cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2011;19(10):1519–1526. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0977-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dorros SM, Card NA, Segrin C, Badger TA. Interdependence in women with breast cancer and their partners: an interindividual model of distress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(1):121–125. doi: 10.1037/a0017724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Badger TA, Segrin C, Hepworth JT, Pasvogel A, Weihs K, Lopez AM. Telephone-delivered health education and interpersonal counseling improve quality of life for Latinas with breast cancer and their supportive partners. Psycho-oncology. 2013;22(5):1035–1042. doi: 10.1002/pon.3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marshall CA, Larkey LK, Curran MA, Weihs KL, Badger TA, Armin J, Garcia F. Considerations of culture and social class for families facing cancer: the need for a new model for health promotion and psychosocial intervention. Families, Systems & Health. 2011;29(2):81–94. doi: 10.1037/a0023975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wells JN, Cagle CS, Bradley P, Barnes DM. Voices of Mexican American caregivers for family members with cancer: on becoming stronger. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2008;19(3):223–233. doi: 10.1177/1043659608317096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marshall CA, Curran MA, Koerner SS, Kroll T, Hickman AC, Garcia F. Un Abrazo Para La Familia: an evidenced-based rehabilitation approach in providing cancer education to low-SES Hispanic co-survivors. Journal of Cancer Education. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0593-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Council of La Raza (NCLR) [Accessed 1 May 2014.];Fortaleciendo la Familia Hispana: Approaches to Strengthening the Hispanic Family. Summary of Best Practices. 2010 http://www.nclr.org/images/uploads/pages/AMS/2010_FSA_Best_Practices.pdf.

- 32.Beck JS. Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. New York, NY: Guilford Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobs BJ. The Emotional Survival Guide for Caregivers: Looking After Yourself and Your Family While Helping an Aging Parent. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minkler M, Garcia AP, Rubin V, Wallerstein N. Community-based participatory research: A strategy for building healthy communities and promoting health through policy change. A Report to The California Endowment. University of California, Berkeley School of Public Health; 2012. [Accessed 1 October 2014.]. http://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/paper-minkler-et-al.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.PCORI (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute) [Accessed 1 May 2014.];PCORI Patient and Family Engagement Rubric. 2014 http://www.pcori.org/assets/2014/02/PCORI-Patient-and-Family-Engagement-Rubric.pdf.

- 36.PCORI (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute). [Accessed 9 May 2014.];Improving quality of life for Latinas with breast cancer. http://www.pcori.org/funding-opportunities/pfa-awards/pilot-projects/latina-breast-cancer-intervention/

- 37.PCORI (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute) Nueva Vida intervention: Improving QOL in Latina breast cancer survivors and their caregivers. Kristi Graves, Principal Investigator; [Accessed 1 October 2014.]. http://www.pcori.org/research-results/2013/nueva-vida-intervention-improving-qol-latina-breast-cancer-survivors-and-their. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallagher-Thompson D, Solano N, Coon D, Arean P. Recruitment and retention of latino dementia family caregivers in intervention research: issues to face, lessons to learn. The Gerontologist. 2003;43(1):45–51. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woodward AM, Dwinell AD, Arons BS. Barriers to mental health care for Hispanic Americans: a literature review and discussion. Journal of Mental Health Administration. 1992;19(3):224–236. doi: 10.1007/BF02518988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chinman M, Hunter SB, Ebener P, Paddock SM, Stillman L, Imm P, Wandersman A. The getting to outcomes demonstration and evaluation: an illustration of the prevention support system. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41(3–4):206–224. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9163-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Napoles AM, Ortiz C, O’Brien H, Sereno AB, Kaplan CP. Coping resources and self-rated health among Latina breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2011;38(5):523–531. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.523-531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. [Accessed 1 October 2014.];Gilda’s Club New York City. http://www.gildasclubnyc.org/index.php.

- 43.Latinas Contra Cancer. [Accessed 1 October 2014.]; http://www.latinascontracancer.org/

- 44.Nueva Vida. [Accessed 1 October 2014.]; http://www.nueva-vida.org/

- 45.SHARE Cancer Support. [Accessed 1 October 2014.];Self-Help for Women with Breast or Ovarian Cancer. http://www.sharecancersupport.org/share-new/

- 46.Antshel KM. Integrating culture as a means of improving treatment adherence in the Latino population. Psychology, Health, & Medicine. 2002;7(4):435–449. doi: 10.1080/1354850021000015258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cancer Support Community, Nueva Vida. [Accessed 1 October 2014.];Frankly Speaking About Cancer. De Cuidador a Cuidador. 2010 http://www.cancersupportcommunity.org/General-Documents-Category/Education/FSAC-Breast-Cancer-Caregiver-Guide-Spanish.pdf.

- 48.Interian A, Ang A, Gara MA, Link BG, Rodriguez MA, Vega WA. Stigma and depression treatment utilization among Latinos: utility of four stigma measures. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61(4):373–379. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.4.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, US: Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berg CA, Upchurch R. A developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(6):920–954. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, Gershon R, Cook K, Reeve B, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Medical Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2010;63(11):1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riley WT, Rothrock N, Bruce B, Christodolou C, Cook K, Hahn EA, Cella D. Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) domain names and definitions revisions: further evaluation of content validity in IRT-derived item banks. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19(9):1311–1321. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9694-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rothrock NE, Hays RD, Spritzer K, Yount SE, Riley W, Cella D. Relative to the general US population, chronic diseases are associated with poorer health-related quality of life as measured by the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2010;63(11):1195–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eremenco SL, Cella D, Arnold BJ. A comprehensive method for the translation and cross-cultural validation of health status questionnaires. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2005;28(2):212–232. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anderson EE. CIRTification: Community Involvement in Research Training. Facilitator Manual. Center for Clinical and Translational Science, University of Illinois at Chicago; 2012. [Accessed 1 October 2014.]. http://www.ccts.uic.edu/sites/default/files/uploads/Facilitator%20Manual.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pan Y, de la Puente M. Census Bureau Guidelines for the Translation of Data Collection Instruments and Supporting Materials: Documentation on How the Guideline was Developed. Statistical Research Division, U.S. Bureau of the Census; Washington, DC: 2005. [Accessed 1 October 2014.]. Criteria for achieving a good translation. Census Bureau guideline: Language translation of data collection instruments and supporting materials. https://www.census.gov/srd/papers/pdf/rsm2005-06.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yost KJ, Eton DT, Garcia SF, Cella D. Minimally important differences were estimated for six Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-Cancer scales in advanced-stage cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2011;64(5):507–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9(2):183–205. doi: 10.1177/07399863870092005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.PROMIS (Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System), National Institutes of Health. [Accessed 9 May 2014.];Measures. Available instruments. http://www.nihpromis.org/measures/availableinstruments.

- 61.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2000;26(2):191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baxter NN, Goodwin PJ, McLeod RS, Dion R, Devins G, Bombardier C. Reliability and validity of the body image after breast cancer questionnaire. The Breast Journal. 2006;12(3):221–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Applied Research, Cancer Control and Population Sciences, & National Cancer Institute. [Accessed 9 May 2014.];What is the ECHOS-NHL Study? http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/echos-nhl/

- 64.Broadhead WE, Gehlbach SH, de Gruy FV, Kaplan BH. The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire. Measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Medical Care. 1988;26(7):709–723. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1979;41(3):209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Winkel G, Jandorf L, Redd W. The Group-Based Medical Mistrust Scale: psychometric properties and association with breast cancer screening. Preventive Medicine. 2004;38(2):209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marshall GN, Hays RD. The Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short-Form (PSQ-18) RAND Corp; Santa Monica: CA: 1994. [Accessed 9 May 2014.]. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/papers/2006/P7865.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Martinez NC, Sousa VD. Cross-cultural validation and psychometric evaluation of the Spanish Brief Religious Coping Scale (S-BRCS) Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2011;22(3):248–256. doi: 10.1177/1043659611404426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lewis FM. Family Home Visitation Study Final Report. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Heitzmann CA, Merluzzi TV, Jean-Pierre P, Roscoe JA, Kirsh KL, Passik SD. Assessing self-efficacy for coping with cancer: development and psychometric analysis of the brief version of the Cancer Behavior Inventory (CBI-B) Psycho-oncology. 2011;20(3):302–312. doi: 10.1002/pon.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Merluzzi TV, Philip EJ, Vachon DO, Heitzmann CA. Assessment of self-efficacy for caregiving: the critical role of self-care in caregiver stress and burden. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2011;9(1):15–24. doi: 10.1017/S1478951510000507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]