Abstract

Alcohol is the Answer! Ruthenium(II) complexes catalyze the C-C coupling of 1,1-disubstituted allenes and fluorinated alcohols to form homoallylic alcohols bearing all-carbon quaternary centers with good to complete levels of diastereoselectivity. Whereas fluorinated alcohols are relatively abundant and tractable, the corresponding aldehydes are often not commercially available due to their instability.

Keywords: Ruthenium, Fluorine, Transfer Hydrogenation, Diastereoselectivity, Green Chemistry

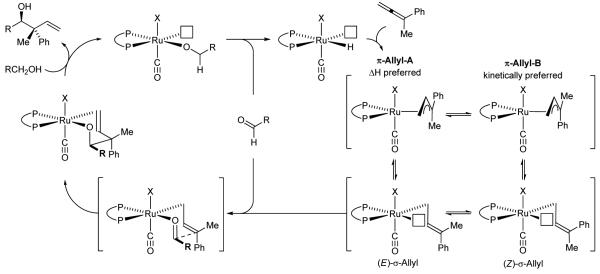

Over 20% of approved pharmaceutical agents and 30-40% of commercially available agrochemicals are organofluorine compounds.[1] Accordingly, many powerful methods for the introduction of fluorine and fluorine containing functional groups have been developed.[2] Remarkably, despite years of intensive investigation, there is a surprising paucity of methods for the addition of non-stabilized C-nucleophiles to fluorinated aldehydes[3] and, to our knowledge, metal catalyzed additions of C-nucleophiles to fluorinated aldehydes are largely restricted to carbonyl ene, Mukaiyama aldol and Friedel-Crafts reactions.[4] These methodological deficiencies likely stem from the intractability of fluorinated aldehydes and their propensity to engage in self-condensation or suffer reduction upon exposure to main group organometallics such as Grignard reagents.[3a,b] In contrast, the corresponding fluorinated alcohols are stable, abundant and relatively inexpensive; so much so they are often used as solvents, cosolvents or additives in chemical synthesis (Figure 1).[5]

Figure 1.

Fluorinated alcohols vs. fluorinated aldehydes.

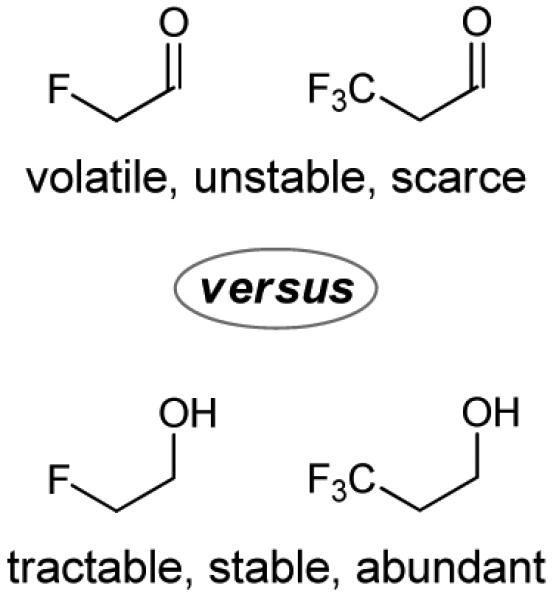

Under the conditions of redox-triggered carbonyl addition,[6] alcohols serve as synthetic equivalents to their carbonyl congeners, enabling additions that would otherwise be unattainable due to the intractability of the corresponding aldehydes. For example, 1,3-dialdehydes are relatively unstable, yet the corresponding 1,3-diols are highly tractable and can be used in catalytic enantioselective double allylations or crotylations via redox-triggered carbonyl addition.[7] In such redox-triggered carbonyl additions, hydrogen is transferred from alcohols to π-unsaturated reactants to generate transient carbonyl-organometal pairs that combine to form products of addition.[6] As the aldehyde is generated pairwise with an organometallic nucleophile it does not accumulate, mitigating competing decomposition. The feasibility of engaging fluorinated alcohols in redox-triggered carbonyl addition was rendered uncertain by three issues: (a) the relatively high strength of carbinol C-H bonds in fluorinated alcohols,[8] (b) the increased endothermicity of dehydrogenation, which being reversible would shorten the lifetime of the transient aldehyde,[9] and (c) the large destabilizing effect of fluoroalkyl groups on the transition state for β-hydride elimination (up to 15 kcal/mol)[9] (Figure 2). Here, we report that certain fluorinated alcohols are capable of participating in redox-triggered carbonyl allylation, as illustrated by their regio- and diastereoselective ruthenium catalyzed C-C coupling to 1,1-disubstituted allenes to furnish adducts bearing all-carbon quaternary stereocenters.[10,11,12,13] Further, through a series of experiments, including competition kinetics, we demonstrate that the alcohol dehydrogenation events in these processes occur near the energetic limit of β-hydride elimination.

Figure 2.

Inductive fluoroalkyl moieties raise the energetic barrier to β-hydride elimination in dehydrogenations of fluorinated alcohols.

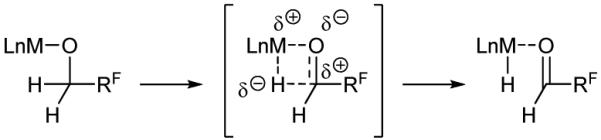

In initial experiments, ethanol and the fluoroethanols 1a-1c were treated with allene 2a under conditions for the coupling of non-fluorinated alcohols to 1,1-disubstituted allenes (eq. 1).[11e] Exposure of trifluoroethanol 1a and allene 2a to the ruthenium(II) catalyst derived in situ from the commercially available components HClRu(CO)(PPh3)3 and dippf [bis(diisopropylphosphino)ferrocene] in THF solvent at 75 °C did not provide any detectable quantity of the desired adduct 3a. However, as anticipated based on the relative transition state energies for β-hydride elimination,[9] reaction efficiency increases with decreasing degree of fluoro-substitution. The reaction of difluoroethanol 1b and fluoroethanol 1c delivered the desired adducts 3b and 3c in less than 5% and 60% yield, respectively, whereas the reaction of ethanol itself provided adduct 3d in 73% yield as a single diastereomer (eq. 1).

aCited yields are of material isolated by silica gel chromatography. Stereoisomeric ratios were determined by 1H NMR analysis of crude reaction mixtures. See supporting information for further experimental details.

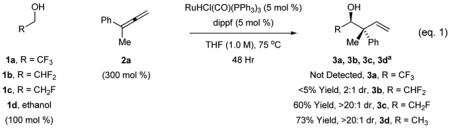

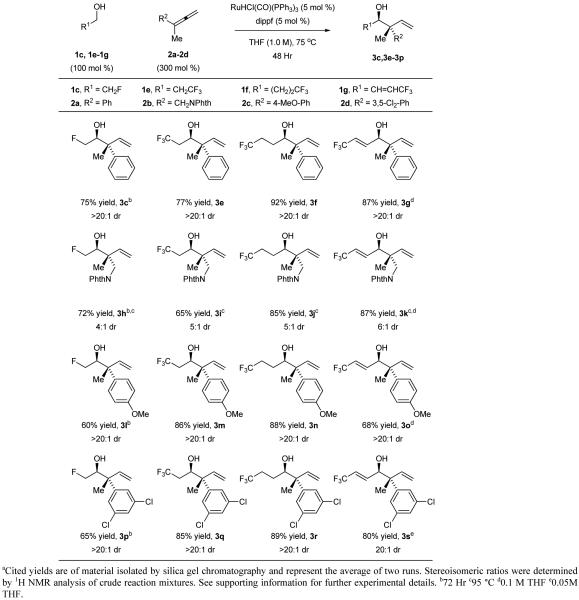

Despite considerable effort to enhance conversion in the reactions of trifluoroethanol 1a and difluoroethanol 1b through variation of ligand, ruthenium precatalyst and other parameters, no significant improvement was possible. In contrast, for the reaction of fluoroethanol 1c and allene 2a, simply extending the reaction time allowed the desired adduct 3c to be obtained in 75% isolated yield. In general, the coupling of fluorinated alcohols occurs under essentially the same conditions as non-fluorinated alcohols,[11e] but longer reaction times are required. Thus, fluorinated alcohols 1c-1e were each reacted with 1,1-disubstituted allenes 1c, 1e-1g to furnish the adducts 3c, 3e-3s in good yields (Table 1). Remarkably, in reactions of the saturated fluorinated alcohols 1c, 1e-1g with 1-methyl-1-aryl substituted allenes 2a, 2c and 2d, complete levels of anti-diastereoselectivity are observed, as determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixtures. Even for the phthalimidomethyl substituted allene 2b, good levels of anti-diastereoselectivity (4:1 - 5:1 dr) are evident in the formation of adducts 3h-3j. For other dialkyl substituted allenes, the transient (E)- and (Z)-σ-allylruthenium intermediates are quite similar in energy resulting in lower diastereoselectivity. Conversion of the trifluoromethylated allylic alcohol 1g to adducts 3g, 3k, 3o and 3s is noteworthy, as fluorinated allylic alcohols are known to undergo internal redox isomerization upon exposure to closely related ruthenium(II) catalysts.[14] The organofluorine compounds generated using the present catalytic methods raise numerous possibilities in terms of synthetic applications. For example, as illustrated in the conversion of adduct 3i to the β-amino ester 5i, novel CF3-containing non-proteinogenic amino acids are readily accessible (eq. 2).[15]

Table 1.

Ruthenium catalyzed hydrohydroxyalkylation of 1,1-disubstituted allenes 2a-2d with fluorinated alcohols 1c, 1e-1g to form adducts 3c, 3e-3s.a

|

Cited yields are of material isolated by silica gel chromatography. See supporting information for further experimental details.

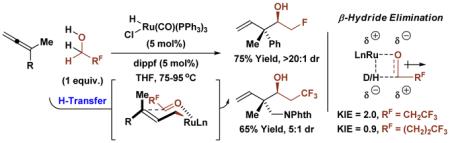

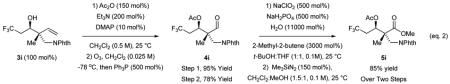

Our collective data suggests the following catalytic mechanism (Scheme 1).[11] The ruthenium hydride complex derived from HClRu(CO)(PPh3)3 and dippf engages in allene hydrometallation to form a nucleophilic allylruthenium complex. The stoichiometric reaction of HXRu(CO)(PR3)3 (X = Cl, Br) with allenes or dienes to furnish π-allylruthenium complexes has been described.[16] Although hydrometallation from the allene π-face proximal to the smaller methyl group is anticipated to be kinetically preferred, rapid isomerization of π-Allyl B enables conversion to the more stable complex π-Allyl A.[11e,17] Carbonyl addition by way of the (E)-σ-allylruthenium complex through a chair-like transition structure forms the anti-diastereomer. Protonolysis of the resulting homoallylic ruthenium alkoxide with a reactant alcohol releases the product and provides a primary ruthenium alkoxide, which upon β-hydride elimination delivers aldehyde, regenerating the ruthenium hydride to close the catalytic cycle.

Scheme 1.

General catalytic mechanism for the redox-triggered coupling of primary alcohols with allenes.

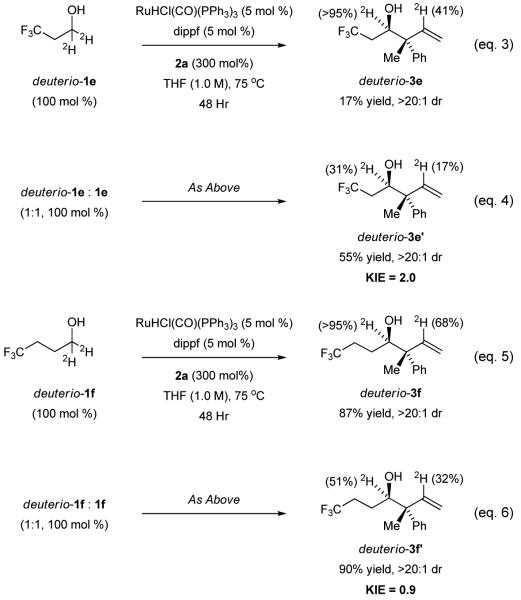

To corroborate the anticipated effects of fluorination on the β-hydride elimination event,[9] a series of competition kinetics experiments were undertaken (Scheme 2). Coupling of deuterio-3,3,3-trifluoropropanol 1e, which is fully deuterated at the carbinol position (i.e. > 95% 2H), with allene 2a under standard conditions delivered deuterio-3e in 17% yield (eq. 3). For deuterio-3e, deuterium is completely retained at the carbinol position, suggesting that the secondary alcohol product is inert with respect to dehydrogenation. Incomplete deuterium incorporation at the interior vinylic position of deuterio-3e (41% 2H) may be due to β-hydride elimination of the allylruthenium intermediate to form diene byproducts, which are detected in crude reaction mixture and may account for the requirement of excess allene. Adventitious water also may diminish the extent of deuterium incorporation.[18] The relatively low isolated yield of deuterio-3e compared to non-isotopically labeled material 3e already suggests that the dehydrogenation events involving alcohols deuterio-1e or 1e are turn-over limiting. Indeed, when this transformation is conducted using equimolar quantities of 1e and deuterio-1e, a primary kinetic isotope effect of 2.0 is observed in the formation of deuterio-3e’ (eq. 4). Furthermore, when an analogous set of experiments was performed on deuterio-4,4,4-trifluorobutanol 1f (eq. 5, 6), for which the inductive CF3 moiety is more distant from the carbinol position, a kinetic isotope effect of 0.9 is observed. These data suggest that for 4,4,4-trifluorobutanol 1f, β-hydride elimination is no longer turn-over limiting and that an inverse secondary isotope effect, associated with turn-over limiting carbonyl addition, may be evident.

Scheme 2.

A transition from turnover-limiting β-hydride elimination to turnover-limiting carbonyl addition in the redox-triggered couplings of fluorinated alcohols 1e and 1f, respectively, as corroborated by competition kinetics.a

aCited yields are of material isolated by silica gel chromatography and represent the average of two runs. Isoptopic composition was determined by 1H and 2H NMR analysis and HRMS. See supporting information for further experimental details.

In summary, redox-triggered carbonyl addition via ruthenium catalyzed transfer hydrogenation allows stable, abundant fluorinated alcohols to serve as synthetic equivalents to intractable fluorinated aldehydes, representing a broad, new means of accessing diverse organofluorine compounds. As specifically shown, the ruthenium complex generated from HClRu(CO)(PPh3)3 and dippf catalyzes the C-C coupling of 1,1-disubstituted allenes with fluorinated alcohols to form homoallylic alcohols bearing all-carbon quaternary centers with good to complete levels of diastereoselectivity. As corroborated by competition kinetics, the partial positive charge accumulating in the transition state for β-hydride elimination of the ruthenium alkoxide poses an increasingly significant energetic barrier for alcohols bearing increasingly inductive fluoroalkyl groups (eq. 1). This insight into the critical role of β-hydride elimination will guide the design of improved second-generation catalyst for the direct C-H functionalization of fluorinated alcohols.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Robert A. Welch Foundation (F-0038), the NIH-NIGMS (RO1-GM069445) and the NIH-NRSA (F31-GM109732) graduate fellowship program (B.S.) for partial support of this research.

References

- [1].a) Thayer AM. Chem. Eng. News. 2006;84:15–24. [Google Scholar]; b) Müller K, Faeh C, Diederich F. Science. 2007;317:1881–1886. doi: 10.1126/science.1131943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wang J, Sánchez-Roselló M, Aceña JL, del Pozo C, Sorochinsky AE, Fustero S, Soloshonok VA, Liu H. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:2432–2506. doi: 10.1021/cr4002879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Ma J-A, Cahard D. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:6119–6146. doi: 10.1021/cr030143e. For selected reviews on methods for the preparation of organofluorine compounds, see: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Brunet VA, O'Hagan D. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:1198–1201. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 1179-1182. [Google Scholar]; c) Bobbio C, Gouverneur V. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006;4:2065–2075. doi: 10.1039/b603163c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Audouard C, Ma J-A, Cahard D. Adv. Org. Synth. 2006;2:431–461. [Google Scholar]; e) Ma J-A, Cahard D. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:PR1–PR43. doi: 10.1021/cr800221v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Cao L-L, Gao BL, Ma S-T, Liu Z-P. Curr. Org. Chem. 2010;14:889–916. [Google Scholar]; g) Kang YK, Kim DY. Curr. Org. Chem. 2010;14:917–927. [Google Scholar]; h) Cahard D, Xu X, Couve-Bonnaire S, Pannecoucke X. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:558–568. doi: 10.1039/b909566g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Nie J, Guo H-C, Cahard D, Ma J-A. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:455–529. doi: 10.1021/cr100166a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Besset T, Schneider C, Cahard D. Angew. Chem. 2012;124:5134–5136. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201012. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 5048-5050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Studer A. Angew. Chem. 2012;124:9082–9090. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 8950-8958. [Google Scholar]; l) Chen P, Liu G. Synthesis. 2013;45:2919–2939. [Google Scholar]; m) Liang T, Neumann CN, Ritter T. Angew. Chem. 2013;125:8372–8423. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206566. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 8214-8264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) McBee ET, Pierce OR, Higgins JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952;74:1736–1737. Very few systematic studies on the addition of organomagnesium, organolithium or organozinc reagents to fluorinated aldehydes exist: [Google Scholar]; b) McBee ET, Pierce OR, Meyer DD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955;77:83–86. [Google Scholar]; c) Ishikawa N, Moon MGK, Kitazume T, Sam KC. J. Fluorine Chem. 1984;24:419–430. [Google Scholar]; d) Steves A, Oestreich M. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009;7:4464–4469. doi: 10.1039/b911534j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mikami K, Itoh Y, Yamanaka M. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:1–16. doi: 10.1021/cr030685w. Metal catalyzed additions of C-nucleophiles to fluorinated aldehydes are largely restricted to carbonyl ene, Mukaiyama aldol and Friedel-Crafts reactions: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Shuklov IA, Dubrovina NV, Börner A. Synthesis. 2007:2925–2943. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ketcham JM, Shin I, Montgomery TP, Krische MJ. Angew. Chem. 2014;126:9294–9302. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403873. For a recent review on C-C bond forming transfer hydrogenation, see: Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 9142-9150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Lu Y, Kim IS, Hassan A, Del Valle DJ, Krische MJ. Angew. Chem. 2009;121:5118–5121. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901648. For use of 1,3-diols as synthetic equivalents to 1,3-dialdehydes in double catalytic enantioselective allylation and crotylation, see: Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 5018-5021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gao X, Han H, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:12795–12800. doi: 10.1021/ja204570w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Song K-S, Liu L, Guo Q-X. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:9909–9923. [Google Scholar]; b) Morozov I, Gligorovski S, Barzaghi P, Hoffmann D, Lazarou YG, Vasiliev E, Herrmann H. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 2008;40:174–188. [Google Scholar]; c) Shi J, He J, Wang H-J. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2011;24:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Gellman AJ, Dai Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:714–722. [Google Scholar]; b) Gellman AJ, Buelow MT, Street SC. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2000;104:2476–2485. [Google Scholar]; c) Li X, Gellman AJ, Sholl DS. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2005;228:77–82. [Google Scholar]; d) Li X, Gellman AJ, Sholl DS. Surface Sci. 2006;600:L25–L28. [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Kumar DJS, Madhavan S, Ramachandran PV, Brown HC. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 2000;11:4629–4632. The allylboration of fluorinated aldehydes has been reported, but modest isolated yields are obtained: [Google Scholar]; b) Ramachandran PV, Padiya KJ, Rauniyar V, Reddy MVR, Brown HC. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:1015–1017. [Google Scholar]; c) Ramachandran PV, Padiya KJ, Rauniyar V, Reddy MVR, Brown HC. J. Fluorine Chem. 2004;125:615–620. [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Ngai M-Y, Skucas E, Krische MJ. Org. Lett. 2008;10:2705–2708. doi: 10.1021/ol800836v. For ruthenium catalyzed allene hydrohydroxyalkylation with non-fluorinated alcohols and related allene-aldehyde reductive couplings, see: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Skucas E, Zbieg JR, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5054–5055. doi: 10.1021/ja900827p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Grant CD, Krische MJ. Org. Lett. 2009;11:4485–4487. doi: 10.1021/ol9018562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Zbieg JR, McInturff EL, Krische MJ. Org. Lett. 2010;12:2514–2516. doi: 10.1021/ol1007235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Zbieg JR, McInturff EL, Leung JC, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:1141–1144. doi: 10.1021/ja1104156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Sam B, Montgomery TP, Krische MJ. Org. Lett. 2013;15:3790–3793. doi: 10.1021/ol401771a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Bower JF, Skucas E, Patman RL, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15134–15135. doi: 10.1021/ja077389b. For iridium catalyzed allene hydrohydroxyalkylation with non-fluorinated alcohols and related allene-aldehyde reductive couplings, see: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Han SB, Kim IS, Han H, Krische MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:6916–6917. doi: 10.1021/ja902437k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Moran J, Preetz A, Mesch RA, Krische MJ. Nat. Chem. 2011;3:287–290. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Ma S. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2829–2872. doi: 10.1021/cr020024j. For selected reviews encompassing intermolecular metal catalyzed C-C couplings of allenes, see: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yu S, Ma S. Angew. Chem. 2012;124:3128–3167. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 3074-3112. [Google Scholar]; c) Lu T, Lu Z, Ma Z-X, Zhang Y, Hsung RP. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:4862–4904. doi: 10.1021/cr400015d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bizet V, Pannecoucke X, Renaud J-L, Cahard D. Angew. Chem. 2012;124:6573–6576. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200827. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 6467-6470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].a) Tarui A, Sato K, Omote M, Kumadaki I, Ando A. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010;352:2733–2744. For recent reviews on the synthesis and properties of fluorinated amino acids, see: [Google Scholar]; b) Mikami K, Fustero S, Sánchez-Roselló M, Aceña JL, Soloshonok V, Sorochinsky A. Synthesis. 2011:3045–3079. [Google Scholar]; c) Qiu X-L, Qing F-L. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011:3261–3278. [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Hiraki K, Ochi N, Sasada Y, Hayashida H, Fuchita Y, Yamanaka S. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1985:873–877. For the stoichiometric reaction of HXRu(CO)(PR3)3 (X = Cl, Br) with allenes or dienes to furnish π-allylruthenium complexes, see: [Google Scholar]; b) Hill AF, Ho CT, Wilton-Ely JDET. Chem. Commun. 1997:2207–2208. [Google Scholar]; c) Xue P, Bi S, Sung HHY, Williams ID, Lin Z, Jia G. Organometallics. 2004;23:4735–4743. [Google Scholar]

- [17].a) Barnard CFJ, Daniels BJA, Holland PR, Mawby RJ. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1980:2418–2424. π-Allylruthenium complexes of the type Ru(η3-allyl)(X)(CO)(PR3)2 are highly fluxional in nature: [Google Scholar]; b) Hiraki K, Matsunaga T, Kawano H. Organometallics. 1994;13:1878–1885. [Google Scholar]; c) Sasabe H, Nakanishi S, Takata T. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2002;5:177–180. [Google Scholar]; d) Cadierno V, Crochet P, Díez J, Garciá-Garrido SE, Gimeno J. Organometallics. 2003;22:5226–5234. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tse SKS, Xue P, Lin Z, Jia G. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010;352:1512–1522. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.