Background

As the number of children in the United States with complex chronic conditions (CCC) grows, so too does our understanding of their unique care needs and the daily challenges faced by family members as they provide this care. An extensive body of literature now exists that defines and describes this group of children (Feudtner et al., 2003; Gordon et al., 2007; Harrigan, Ratliffe, Patrinos, & Tse, 2002; Srivastava, Stone, & Murphy, 2005) and that identifies the unique challenges they and their families face in navigating the healthcare system and engaging in life in the “normal” world (Kirk, Glendinning, & Callery, 2005; Ray, 2002; Reeves, Timmons, & Dampier, 2006; Rehm & Bradley, 2005a, 2005b). The literature that has accumulated over the past 25 years has contributed to improvements in care for these children and their families, but it has also raised questions about current care delivery systems and identified gaps in our knowledge base. Among the most significant of those gaps is how to help HCPs develop the skills necessary to build strong working relationships with families, thereby promoting optimal care for some of our most vulnerable children.

Patient and family-centered care (PFCC), a model that recognizes the family as expert in the care of their child and that seeks to establish and maintain a partnership between family and provider, is the gold standard in pediatrics and is widely accepted as the philosophy of care upon which optimal pediatric healthcare practice is built. Professional organizations and government agencies have endorsed PFCC, and it has become an established part of the curriculum in programs that train future pediatric providers (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2012; American Nurses Association, 2008). The following components are generally considered to be key elements of the PFCC model: respect for family preferences; flexibility and customization of care; honest information sharing to promote participatory decision-making; collaboration across all levels of the healthcare delivery system; and a strengths-based approach to working with patients and families (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2012; Institute for Patient and Family-Centered Care, 2010; Jolley & Shields, 2009; Malusky, 2004; Mikkelsen & Frederiksen, 2011; Shields et al., 2012). Despite widespread acceptance of the concepts of PFCC, implementation has remained a challenge in pediatric healthcare settings, with families reporting widely disparate experiences in the quality and family-centeredness of the care they receive (Balling & McCubbin, 2001; Davies, Baird, & Gudmundsdottir, 2013; Graham, Pemstein & Curley, 2009). The inpatient, acute care setting has historically not provided optimal PFCC and has particularly struggled with the PFCC concepts of respect for family preferences and flexibility and customization of care. Traditional practices such as visitation restrictions and family exclusion from care planning and the rounding process have limited the extent to which PFCC was achieved (Meert, Clark, & Eggly, 2013; Uhl, Fisher, Docherty, & Brandon, 2013). Children with CCC and their families are the ones most in need of this type of care, and a failure to engage the family in a partnership and to recognize the expertise that they have regarding the care of their child can have detrimental effects upon the family and can result in unnecessary, wasteful, and potentially harmful care.

Yet, some families do experience care that acknowledges and respects the expertise they bring; there are healthcare providers who embrace the concept of PFCC and consistently incorporate it into their practice (Davies et al., 2013). Efforts to improve the quality of care for children, particularly for those with CCC, must focus on these providers, understanding how they engage with families and how they operate within the busy and complex context of the modern healthcare environment. The pediatric intensive care unit is a natural setting in which to explore interactions with such providers because it is a high-stress, high-stakes environment with rapidly-evolving care situations necessitating frequent and, at times, complex communication with families. Further, a large percentage of the patients who receive care in the PICU are children with CCC (Edwards et al, 2012; Namachivayam et al., 2012).

The data presented in this paper are one component of the analysis from a qualitative, grounded theory study, the overall goal of which was to identify best practices in parent/nurse interactions in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) setting for the parents of children with CCC. Some of the strongest themes from the data centered around the existence and enforcement of rules in the PICU and the implicit rules, or social norms (Bicchieri, 2006), that guided practice in that environment. Emerging from these themes was an understanding of the ways in which the model of PFCC, as currently conceptualized, fails to adequately account for the context in which parent/nurse interactions are occurring and the ways in which existing social norms may run counter to the goal of delivering optimal PFCC. This paper adds to the existing literature by exploring these two important contextual factors that challenge the delivery of PFCC in the inpatient setting. Although context is implicit in the existing model of PFCC, the model may need to more fully explicate these factors in order to for PFCC to be fully actualized in pediatric healthcare settings.

Methods

This grounded theory study had, as its foundation, the sociological theory of symbolic interactionism, which posits that meaning is central to understanding human behavior and that it is a social product, derived from a person’s interactions with others. Social interaction is therefore central to the creation of meaning, and social researchers are thus charged with studying and understanding how and why interactions occur and the meanings individuals derive from those interactions (Blumer, 1969; Hall, 1987; Strauss, 1993). Grounded theory and symbolic interactionism have been described as a “theory/methods package” (Clarke, 2005, p. 4) because of grounded theory’s emphasis on understanding interaction, social processes, and interpretation of meaning. Accordingly, this study sought to understand interactions, processes, and the creation of meaning for the parents of children with CCC and nurses in the PICU.

A single PICU in a large, urban teaching hospital in the western United States served as the data collection site, and the first author was the sole data collector. Approval from the local institutional review board was obtained prior to the start of data collection, and guidelines for the ethical conduct of research were followed throughout the study process. Eligibility criteria for parents included: age greater than 18 years, English-speaking, and being the parent of a child with a CCC who was currently admitted to the PICU and who had an expected length of stay in the PICU of at least seven days. Parents who agreed to participate allowed the investigator to observe their interactions with healthcare providers from the child’s room in the PICU at various times over the course of a week. Near the end of that week, parent participants also engaged in a single, in-depth interview that asked questions about their experiences with healthcare providers while in the PICU. Conducting the interview while the child was still hospitalized in the PICU provided parents with an opportunity to report and to reflect in “real time” on their experiences and may have helped to highlight some of the day-to-day concerns that would be lost in a more traditional retrospective interview. Parents were invited to begin the discussion by describing their child, including a brief summary of their child’s illness and their past experiences in the healthcare system. During the course of the observations and interviews, parents also helped identify their key healthcare providers, and these providers were invited to participate in a separate in-depth interview. All formal interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service, and the first author verified each interview after transcription. Field notes were taken during each observation session and during additional general observation sessions on the unit, during which time the investigator sat at the nurses’ stations in the unit to observe movement about the unit, workflow, and the type and frequency of exchanges that happen outside of patients’ rooms. Additional data collection came in the form of participation in unit staff meetings and review of relevant texts, including policies, guidelines, and materials distributed to families during their stay in the PICU.

There were a total of 19 participants in the study, 7 parents (5 mothers and 2 fathers, all the parents of different children) and 12 nurses (all female). Relevant demographics for these participants are displayed in appendices A and B. Interestingly, 10 of the 12 nurse participants (83.3%) identified as Caucasian, whereas 35% of the registered nurses in the county where this study was conducted are Caucasian (California Health Care Foundation, 2010). Five of the seven parent participants (71.4%) identified as Latino, also higher than the county demographic of 48.2% (United States Census Bureau, 2014).

This study was conducted using a constructivist, postmodern conceptualization of grounded theory that focuses on “theorizing” rather than theory production and questions the usefulness of focus on a single core category, suggesting that it may lead to oversimplification of complex social processes (Charmaz, 2006; Clarke, 2005). Consistent with Clarke’s conceptualization of postmodern grounded theory, situational analysis, which focuses on the contextual nature of data, positionality, and awareness of and illumination of discourses, provided a guiding framework for the analytical work.

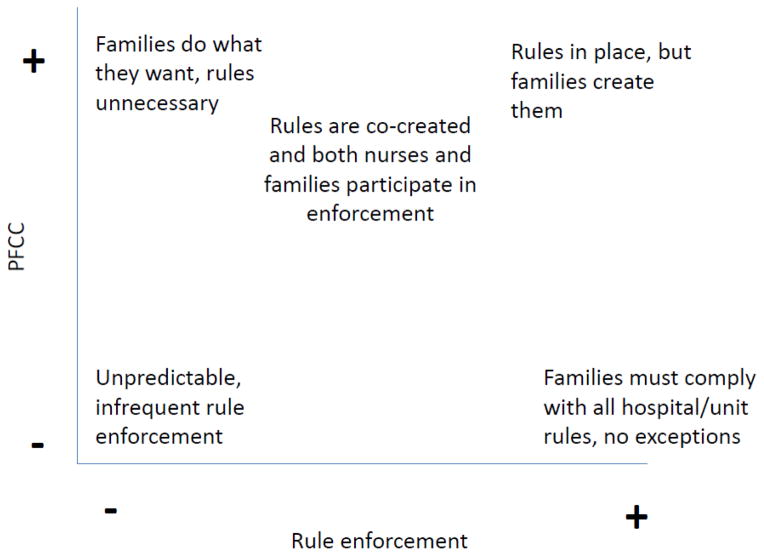

The first step in data analysis was open coding of the interviews, field notes, and policy documents. Frequently occurring initial codes relevant to this analysis included “rules,” “enforcement,” and “expectations.” These initial codes were later clustered into groups in the process of axial coding, or the linking of open codes together into categories for further exploration and analysis (Charmaz, 2006). This analysis occurred in memos about many of the identified categories, including the set of rules that families are expected to follow, the differences between the explicit and implicit rules, and the ways in which families learn these rules. Writing memos on these topics allowed deeper exploration of these themes and recognition of the need for more information. In subsequent data collection, information that specifically solicited content about rules and rule enforcement on the part of the nurse was sought. Consistent with grounded theory methods, constant comparative analysis, in which new cases are compared to existing ones to identify similarities and differences that advance the analysis (Corbin & Strauss, 2008), occurred throughout the analytical process. As a component of the analysis, the raw data, codes, and themes were compared and contrasted, which allowed for similarities and differences in the data to be highlighted and further examined. This ongoing comparison was particularly helpful in understanding the competing priorities that nurses face related to rule enforcement and the differences in perceptions of these rules between nurses and family members. The construction of situational and positional maps, key components of the situational analysis toolbox (Clarke, 2005), helped to provide additional insight into these competing priorities and varying standpoints. The situational maps, which attempt to capture the full scope of the situation by listing all relevant elements and actors (Clark, 2005), helped to highlight the complex and, at times, chaotic context within which care for children in the PICU is occurring. This in turn helped to shed light on healthcare providers’ need for rules that help to bring structure and control to an otherwise out-of-control environment. Positional maps helped to identify positions within the data, some of which may be hidden, implicit, or otherwise difficult to describe, and none of which are assumed to be better than another for the purposes of analysis (Clark, 2005). An example of a positional map about rule enforcement is shown in Figure A. This map helped to illustrate the dominant positions in the data, as well as those that were under-represented or not represented at all. Rigor in the analytical process was ensured through frequent discussion of findings with members of the research team, and these discussions helped to highlight areas of potential bias and conceptual weakness and the possibility of alternative explanations (Whittemore, Chase, & Mandle, 2001).

Figure.

Rules Positional Map

Example of a positional map created during data analysis

Findings

Although not a topic of inquiry on the initial interview guide for parents or nurses, rules quickly became an important area of focus for both parents and nurses. Consistent with the co-occurring processes of data collection and analysis in grounded theory, the interview guide was subsequently revised to inquire explicitly about formal rules and to seek information about a related emerging theme, implicit rules.

Explicit Rules

Parent perceptions

Family members and visitors of patients in the PICU were introduced early in the hospital admission to the basic rules of the unit. This process of “learning the rules,” one of the codes generated from both parent and observation data, occurred most often through verbal explanation from the admitting nurse. The rules were also documented in the unit welcome packet that was offered to each family at the time of admission. The rules discussed in the welcome packet covered a wide range of topics, from access to the unit and alarm management to isolation status and visitor personal care needs. The rules pertaining to personal care needs were mentioned most frequently by parent participants. These rules were the ones that had the most impact upon their day-to-day life in the PICU and that often became a burden as the length of the hospitalization increased. From this data, the code “struggling with the rules” was generated. This code referred to the challenges that parents faced when they encountered rules that made it difficult to either be with their child when they wanted to or to live for an extended period of time in the PICU. The two rules that parents considered most problematic were the need to leave the unit in order to use the restroom and a ban on family members or visitors eating at the bedside. Although there were three restrooms located within the PICU, all three were designated exclusively for staff member use. This necessitated that parents exit to use visitor restrooms located just outside of the unit, and they then had to call for re-entry to the unit after using the restroom. The need to exit and reenter was a particular frustration during the night time hours, when reduced staffing often meant delays in responding to the parent’s request to reenter the unit. One parent stated:

“There’s not a bathroom inside, so you can’t really … that, to me, really bugs me that you have to every time go out…call, come back.” [Participant M600]

The ban on eating at the bedside was also problematic for several of the parents. Parents and other visitors in the PICU were permitted to have drinks in the patient rooms, but solid foods were prohibited in most cases. Some of the parents complied despite objecting, and others found ways to bypass the rule.

“I mean, I sneak food in. I do eat, but I don’t eat messy stuff. I try not to make crumbs …” [Participant M700]

Those parents who complied with the ban expressed concern about leaving their child’s bedside for extended periods, worrying that the child would awaken and be frightened that the parent was not there or that there would be a deterioration in the child’s condition during his or her absence. Two parents indicated that they had delayed leaving the unit to eat, resulting in extended periods of time during which they had not eaten; this behavior was at least in part due to their inability to have meals or other snacks in their child’s room. Observation periods yielded numerous examples of parents eating on the unit, some having only light snacks and others eating entire meals in their child’s room. This variability in compliance was not confined to the rule about eating, as parents were noted to be “breaking” a variety of rules, including adherence to the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) in the rooms of children on isolation, silencing of alarms within the patient rooms, entry into the unit without prior approval of the RN, and having more than one visitor sleeping overnight in the patient room.

Nurse perceptions

“Enforcing the rules” quickly became a significant area of discussion in interviews with nurse participants and a frequently occurring code, despite the fact that it was not an explicit topic in early iterations of the interview guide. When asked to describe how she learned to communicate with families, one nurse responded,

“I feel like some people just have good communication skills and some people would feel more comfortable than others. Just little things like, ‘Sorry, you can’t eat in here.’ There’ll be nurses that will let [parents] eat in here because they don’t want to tell them, ‘Don’t eat in here.’” [Participant RN203]

This response and subsequent discussion later in the interview suggested that the nurse equated communication with rule enforcement, and she viewed her willingness to engage in such enforcement as evidence of her ability to communicate well with families. Other nurses expressed varying degrees of difficulty with the concept of rule enforcement, leading to the occurrence of “not consistently enforcing the rules” as a frequent code. These nurses noted that enforcement became more difficult when the rules were inconsistently applied. Once the family had “gotten away” with something like eating in the room or not having to wear PPE in the room of a child on isolation status, it was then difficult for some nurses to step in and reestablish the rules.

“A lot of families refuse to wear the precautions. If you are the one to tell them that they need to wear precautions, or, ‘You can’t bring food or drinks in,’ they shut you out…if you try to enforce the rules about contact [isolation] and bringing food in the ICU, they just put you by the wayside after that, like you’re not…” [Participant RN201]

Only one nurse expressed a concern about the impact that enforcement of certain rules could have upon the family’s efforts to be together and to support one another during their child’s hospitalization. This nurse stated that she does sometimes purposefully choose not to enforce rules, not because enforcement in difficult but because of her beliefs about the family situation. She expressed a belief that allowing a father to eat at his child’s bedside or permitting both parents to sleep at the bedside overnight was more important than adherence to a prescribed set of rules that do not take into account the individual family’s needs.

Rule enforcement was a topic of concern not only for the nurse participants in this study, but also for the nursing staff as a whole. Rules were a regular topic of discussion at observed unit staff meetings and a frequent subject of whole-staff emails. Those nurses who most closely identified with the role of rule-enforcer often initiated discussion of the topic at the meetings, but the discussion always generated significant interest, with several nurses speaking up to offer examples of families who failed to comply with the rules and many other nurses offering both verbal and non-verbal affirmations of the frustration expressed by the nurses who spoke. As stories about problems with family rule compliance were shared in these meetings, many nurses were noted to nod their head in agreement or to offer side comments about similar experiences to those sitting nearby. The level of agreement about the need for rule enforcement noted at these meetings was, however, at odds with the extent to which compliance with rules was noted during observations in the unit. With such significant agreement, one would expect to see a high level of compliance with the stated rules. The discordance between these two observations suggests that nurses were perhaps not as confident about the need for such strict rule enforcement or about their role as enforcer as they had let on to their peers.

Intersection of parent and nurse perceptions

The intersection between parent and nurse perceptions of explicit rules occurred in the enforcement of such rules. The extent to which nurses were willing and able to enforce the rules largely dictated the level of parent compliance with the rules. Although many parents were noted to be out of compliance with the rules, an equal number were observed to comply, often without complaint or expressed concern. This created an additional area of concern for the nursing staff: some parents were expected to comply with the rules, while others were allowed to forego compliance and instead engage in whatever behavior best suited their needs. Upon facing a family that was out of compliance with the rules, the nurse was therefore faced with a dilemma: choosing to enforce the rules and risking the ire of the family, or overlooking the lack of compliance and possibly being held accountable for failing to enforce the rules. The inconsistency of rule enforcement on the part of the nursing staff was confusing for the parents and led to questions about the necessity of the rules, which in turn led to rules being either modified or broken by the parents. A cycle of non-compliance was thus created, contributing to frustration on the part of the nursing staff and undermining optimal relationship development between parents and nurses.

Implicit Rules

Of equal impact upon the patient and family experience were the implicit, or unspoken, rules of the PICU, which can also be thought of as the social norms of the hospital setting. These implicit rules/norms were never clearly discussed with families and as a result, parents did not speak directly in the interviews about them. The data to support this finding therefore came from interviews with nurses and observations of interactions between nurses and parents. Because of their implicit nature, families were dependent upon social cues and an understanding of and/or familiarity with the healthcare system in order to successfully navigate these rules. The code “knowing the hospital routine” reflected the fact that parents were expected to know that the hospital had a set schedule that was dependent upon a variety of factors, including the work hours of the nursing staff, the educational needs of the physicians-in-training, and schedules for delivery of supplies and medications. Parent requests to vary or interrupt this schedule were not welcome and may have been perceived as demanding by the nurses, who have learned to structure their work day to accommodate the hospital routine.

“I’ve had families where they want…everything is specific and their needs are written out on paper. [A mom] wanted the meds given at 0800 on the dot, and with change of shift and doing your safety [checks] – it doesn’t happen. She would scold you for not having it done at 0800. It was a lot of pressure and stressful. It was uncomfortable.” [Participant RN201]

Another code, “understanding care priorities,” captured the idea that parents were expected to understand that the nurse’s focus was on care of the child, and that tasks that the nurse perceived as interfering with or delaying the child’s care were given low priority. These tasks included things as basic as retrieving drinks for family and visitors or as complex as engaging in discussion with the family about changes in the child’s condition or the plan of care for the day. Some of the nurses interviewed seemed to have an expectation that parents would be able to read the situation, understand how busy the nurse was, and adapt their questioning or demands upon the nurse accordingly. One nurse stated,

“I think that we sometimes…we let people forget what a serious area that we work in. And that this is an ICU and these people that are here are sick and that’s what we’re doing here. This isn’t like a social gathering in any way…we don’t want to make light of the fact your kid is sick enough to be in the ICU, and that is what we’re here for – to care for them. And that’s our primary concern. Yeah, we want [parents] to have coffee and want [parents] to feel like [they’re] getting free information…we want to recognize that [parents] need information, we want to give it to [them]. But [parents] really shouldn’t interrupt us when we’re giving report. [They] really need to understand that what we’re doing with [their child’s] medications is more important than [their] coffee.” [Participant RN903]

Parents were additionally expected to recognize the expertise that the nurse brought to the bedside; this was captured in the code, “respecting the nurse as professional.” The nurses expressed frustration with parents who offered detailed suggestions on how best to care for their child or who did not respect the nurse’s authority or role as a professional. Some of the nurses’ comments were territorial in nature; they wanted parents to recognize that the PICU was the nurse’s domain and that the nurse – not the parent—was the expert in that domain. One nurse said,

“…And [parents] are kind-of infringing upon my job, and telling me what to do, it’s like that little loss of respect is kind of hard to work with.” [Participant RN901]

Above all, parents were expected to be compliant, easy-going, and emotionally stable and to realize that they were guests in the PICU, regardless of the length of time that their child had been hospitalized in the unit. Parents who failed to meet these standards were labeled as “difficult,” a label that got passed from nurse to nurse during shift report and that could then follow the parents throughout the hospitalization, potentially coloring the interactions that subsequent nurses had with the patient and family.

“…We had a lot of difficult families in the unit. We’ll get report and the nurse already has her opinion. It’s given like, ‘Oh, this family is so difficult…it’s going to be the worst day. The family is so difficult and terrible.’” [Participant RN203]

In rare cases, the labeling of parent behavior was so extreme as to make it challenging to find nurses who were willing to care for a patient and their family:

“With [patient], nobody wanted to take care of her because her mom was so difficult. I had to literally make a stink about making a continuity list for her and picking out, looking at the calendar, and picking out people, this is who’s going to take care of her because otherwise this is going to be a nightmare.” [Participant RN900]

Several of the nurses interviewed expressed frustration with this labeling behavior, preferring not to draw premature conclusions and instead to approach each family with a “blank slate.” These nurses didn’t necessarily have different expectations for parent behavior, but they wanted the opportunity to judge the behavior for themselves or to further investigate the cause of the problematic behavior. Other nurses, however, did make allowances for parents, recognizing that their emotional stress or their lack of familiarity with the PICU environment might lead to behavior considered outside the norm for the hospital setting. One nurse summed up her approach to working with families in this way:

“So [I] just remember if they are asking a lot of questions or if they are, if there are difficult times with them, that they really, really love their child, and you really, really care about your patient—so if nothing else, you really have that in common.” [Participant RN404]

Discussion

The complexity of the modern healthcare environment necessitates the creation of an ever-growing list of rules to which patients, families, and visitors to the hospital are expected to adhere. Many of these rules are designed to promote the safety of everyone in the hospital environment. Few would argue, for example, about the necessity of a set of rules regarding use of PPE to prevent transmission of communicable diseases. These safety-related rules make sense to most visitors, and staff members are easily able to offer rationale for their existence and the necessity of enforcement. These rules are also largely explicit, and they are typically the rules about which families and visitors are informed early on in their visit to the unit. There are, however, many other explicit and implicit rules that do not fall as clearly into the safety category, and they appear to exist either to maintain order in the environment or for the convenience of hospital staff. The explicit rules from these two categories were the ones about which parents expressed the most frustration, and the implicit rules from the same categories were the most problematic for nurses.

This frustration on the part of both parents and nurses over the rules not directly related to safety may be due to the competing perceptions and goals of both groups. Nurses are rapidly socialized into the healthcare environment as a part of their training, both during their formal educational program and upon entry into the workplace (Dinmohammadi, Peyrovi, & Mehrdad, 2013; Price, 2008). They quickly learn institutional norms, the hospital routine, and their role within it, including their responsibility for performing the tasks necessary to ensure safe patient care. They also learn the stumbling blocks to efficient care and have devised mechanisms to avoid such stumbling blocks, often in the form of policies and rules, many of which have a direct impact upon families and visitors. Parents, on the other hand, come to the hospital environment with the goal of ensuring the highest quality care for their child, and they have varying levels of familiarity with the healthcare system and the structures and routines contained therein. Depending upon their past history, parents may not have yet been socialized to the norms of the healthcare environment and to their role within that environment. Further, they are encouraged by other healthcare providers, by family and friends, and by the lay healthcare literature to be an active participant in their child’s care. Parents are repeatedly told to ask lots of questions, advocate for their child, question decisions that do not make sense, and pursue individualized care that matches the routine and the customs of the family (Family Voices, 2013). These very behaviors, though, are the ones that nurses identified as challenging, problematic, and undesired, and that may, paradoxically, subject the family to a lower quality of care by reducing nursing staff engagement with the family.

Why do some nurses find these key tenets of parent participation so problematic? The answer may lie, in part, in an outdated understanding of the parental role within the hospital setting. The norms upon which nurses are basing their expectations of parent behavior are a holdover from a time in which parents were viewed as visitors or guests (Harrison, 2010; Jolley & Shields, 2009) and not as integral members of the child’s care team. The field of pediatrics has endorsed the concept of PFCC for decades, but the extent to which the model has become actualized within the acute care setting remains in question (Jolley & Shield, 2009). Parents repeatedly encounter barriers to full and active participation in their child’s care, whether in the form of limited accommodation of their personal needs during the child’s stay at the hospital or of dismissal of their concerns about the child’s care on the part of the nursing staff. Both of these types of barriers undermine the parent’s role as a member of the care team and serve to maintain the status quo, in which the focus on hospital routine and work efficiency is given priority over the needs of patients and families. These barriers also help to foster the territorialism expressed in several of the nurses’ comments and to promote a hierarchy in which the nurse as professional has power over the parent.

Further, the nurses responsible for simultaneously providing PFCC and for serving as the front-line face of the healthcare system and the de facto rule-enforcer may be experiencing role strain, or the felt stress that occurs in the attempt to meet the expectations of a role with competing demands (Ward, 1986). The emotion with which several of the nurse participants expressed concern and frustration about parental violation of unit rules and norms lends credibility to this assertion; discussion about the rules, in particular the implicit rules/norms, was often one of the most animated sections of the interview. The conflict that exists between the historical role of the parent-as-visitor and the modern conceptualization of the parent-as-team-member is actualized in the day-to-day interactions of parents and nurses, such that the nurse is unsure which role to assume and of the expectations associated with that role. The emergence of the pay-for-performance movement and the accompanying emphasis on ensuring patient and family satisfaction with the hospital experience (Wolosin, Ayala, & Fulton, 2012) has focused attention on the extent to which the hospital environment is patient and family-centered. Unfortunately, nurses have been given little guidance about how to successfully navigate the dualities of their role: the need to maintain safety and order while simultaneously providing an excellent care experience for each patient and family. The end result is a sense of frustration on the part of both the nursing staff and the families that runs contrary to the goal of establishing PFCC.

This analysis thus complicates the PFCC model, suggesting that its challenges to full implementation may lie, in part, in its failure to fully and explicitly contend with contextual factors, of which this discussion of rules and norms are but one example. Nurses are working under a mandate to provide optimal PFCC, but they are being asked to do so in a context that runs contrary to and often demands something other than this type of care. Healthcare institutions create rules and have established norms, and RNs are socialized to work within these contexts such that they embrace and adopt the rules and norms, which in turn makes it difficult for them to take the idealized concepts of PFCC and put them into action. Further, RNs may lack sufficient support to effectively integrate competing demands. Thus, the adherence to rules and norms take precedence, and the discrepancy between what parents are seeking and what RNs provide occurs. The current model of PFCC fails to sufficiently account for this contextual factor and may begin to offer an explanation for the discrepancy between PFCC as a concept that nearly everyone endorses and its adoption in practice, which existing literature and this study suggest may not be optimal. It may be necessary, therefore, to further extend the PFCC model by emphasizing that true partnership between parents and providers can only occur when the importance of context is given adequate attention. This attention to context must include a thorough, ongoing, and self-reflective analysis of the ways in which families experience a particular healthcare setting, taking into account both the explicit and implicit messages that they receive and the impact that socialization to norms and roles have had upon providers working within that setting.

Study Limitations

This was a single-site study and as such, only reflects the policies, practices, and viewpoints of parents and nurses from that site. The specific set of rules to which parents and visitors are expected to adhere varies from hospital to hospital, such that the challenges identified in this paper may not be of concern in other locations. In addition, the nurse participants in this study were a relatively homogenous group; all of the nurses were female, and all but one were Caucasian. While reflective of the demographics of the nursing staff within this unit, it is not representative of the population of nurses in the county in which this study was conducted, and it is likely that the views of male and non-Caucasian nurses are not adequately reflected in the data. The ethnicities of the parent participants are also not fully reflective of those of the county in which this data was collected, and the impact of this discrepancy upon the behaviors and opinions captured here is not known.

The first author was employed part-time as a clinical nurse in the unit in which this study was conducted and as such, had an “insider” status in this environment. Her position as an insider afforded her entrée into the research setting and full access to the workings of the unit. This access facilitated data collection and gave her credibility with the nurse participants, enabling her to gain candid, open feedback about their experiences caring for patients and families in the PICU. This insider status may also, however, have impacted the type and amount of data collected, since this was not an environment that she was experiencing for the first time. Her familiarity with the setting may have predisposed her to see processes, behaviors, and interactions in a particular way. Similarly, data analysis may have been impacted by this insider status, contributing to bias in the analytical process or early attributions based on previous experiences in this known environment. The research team helped to mitigate this by reviewing observation field notes and interview transcripts, looking for ways in which this insider status may have impacted data collection. The team also remained attentive to this status throughout the analytical process by reviewing its impact upon the emerging findings.

Implications for Practice and Research

The findings from this portion of the study indicate that parents encounter significant barriers to full participation in their ill child’s care in the PICU, such that true PFCC is not yet a reality. These barriers arise in the form of both codified rules and in an outdated understanding of the parental role in the hospital setting. Efforts to achieve optimal PFCC may, therefore, require a reevaluation of the existing rules to which families are subject. Is it possible, for example, to design or adapt the environment to accommodate parents’ basic needs? Can existing policies about such things as eating and overnight visitation be modified to maximize the time that families are together? Changes to these rules are certain to have an impact upon staff, and the implications of these changes would need to be evaluated and addressed. Allowing families to eat in the rooms, for example, would necessitate setting guidelines for food storage and may require more frequent rounds by housekeeping staff, in order to remove uneaten food that could attract pests. Permitting more than one family member to stay overnight with the child would similarly require adjustments on the part of the night shift nursing staff, who have become accustomed to providing care with a minimal number of visitors present.

In tandem with a reevaluation of these explicit rules, an educational initiative that explores the value of PFCC and the challenges associated with its provision is needed. This educational effort should go beyond the basics that most nurses receive in their pre-licensure academic programs and instead delve into and begin to challenge the assumptions that practicing nurses bring with them to interactions with patients and families. It would include an identification of the implicit rules to which families are expected to adhere, as well as an evaluation of the extent to which these rules preserve the status quo and undermine parent and family participation in care. This information should be presented in the context of the current healthcare environment and the ACA mandates that are driving organizations to focus significant attention on the extent to which patients and families are satisfied with their healthcare experience (Wolosin, Ayala, & Fulton, 2012). Interventions to improve patient and family satisfaction are necessarily largely focused on nursing care, and nurses must therefore possess both an understanding of the drivers of patient and family satisfaction and a willingness to adapt their care to better meet patient and family needs. Equipped with this knowledge, nurses could identify changes to their own practice and modifications to the unit culture that would foster PFCC. At the same time, nurses need a forum to discuss the difficulties that they face in carrying out the dualities of their role, serving as both facilitator of PFCC and rule enforcer. A need exists for both one-on-one and group coaching, where these nurses can report on challenging family scenarios and receive feedback on how best to handle the situation and support for their efforts to provide optimal PFCC. Working with families in crisis and the parents of children with CCC is a complex endeavor, and it requires a skill set that nurses will not acquire without advanced training and ongoing support. It is time that we acknowledge this fact and afford learning to interact with families the same attention and resources that we give to technical skill acquisition.

Finally, there is a need for further research in this area. The concept of PFCC has garnered significant interest in the pediatric literature, but relatively few studies have investigated the extent to which acute care environments are patient and family-centered or the barriers to achieving this goal. This study identifies some significant barriers within the context of a single PICU environment, but there is a need to expand upon this work, assessing the extent to which these barriers transcend this particular setting. Are these challenges consistent with those encountered in other PICUs, and to what extent are these problems encountered across the pediatric acute care trajectory? If these problems exist in other settings, what interventions are successful in challenging the status quo and improving the patient and family experience? There may also be an opportunity to learn from the significant PFCC work that has been done in neonatal intensive care units (Cooper et al, 2007; Gooding et al. 2011), given some of the similarities between these two environments. Patient and family-centered care is widely accepted as the ideal in pediatric healthcare, but it is time to generate the knowledge that will help transform this ideal into reality.

Acknowledgments

The research described in this article was funded by an individual National Research Service Award from the National Institute for Nursing Research, grant number NIH-5F31NR012093

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jennifer Baird, Email: jennifer.baird@ucsf.edu.

Betty Davies, Email: daviesb@uvic.ca.

Pamela S. Hinds, Email: pshinds@childrensnational.org.

Christina Baggott, Email: baggott@stanford.edu.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Hospital Care and Institute for Patient and Family-Centered Care. Patient- and family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):394–404. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Association. Pediatric nursing scope and standards of practice. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Balling K, McCubbin M. Hospitalized children with chronic illness: Parental caregiving needs and valuing parental expertise. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2001;16(2):110–119. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2001.23157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicchieri C. The grammar of society: The nature and dynamics of social norms. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer H. Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- California Health Care Foundation. California Health Care Almanac. Oakland, CA: Author; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AE. Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the postmodern turn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LG, Gooding JS, Gallagher J, Sternesky L, Ledsky R, Berns SD. Impact of a family-centered care initiative on NICU care, staff, and families. Journal of Perinatology. 2007;27:S32–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Davies B, Baird J, Gudmundsdottir M. Moving family-centered care forward: Bereaved fathers’ perspectives. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing. 2013;15(3):163–170. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0b013e3182765a2a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinmohammadi M, Peyrovi H, Mehrdad N. Concept analysis of professional socialization in nursing. Nursing Forum. 2013;48(1):26–34. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JD, Houtrow AJ, Vasilevskik EE, Rehm RS, Markovitz BP, Graham RJ, Dudley RA. Chronic conditions among children admitted to U.S. pediatric intensive care units: Their prevalence and impact on risk for mortality and prolonged length of stay. Critical Care Medicine. 2012;40(7):2196–2203. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31824e68cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Family Voices. Quality health care for children with special healthcare needs. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.familyvoices.org/admin/work_caring/files/QualityHealthCare.pdf.

- Feudtner C, DiGiuseppe DL, Neff JM. Hospital care for children and young adults in the last year of life: A population-based study. BMC Medicine. 2003;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooding JS, Cooper LG, Blaine AI, Franck LS, Howse JL, Berns SD. Family support and family-centered care in the neonatal intensive care unit: Origins, advances, iimpact. Seminars in Perinatology. 2011;35(1):20–28. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham RJ, Pemstein DM, Curley MAQ. Experiencing the pediatric intensive care unit: Perspective from parents of children with severe antecedent disabilities. Critical Care Medicine. 2009;37(6):2064–2070. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a00578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall PM. Interactionism and the study of social organization. The Sociological Quarterly. 1987;28(1):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan RC, Ratliffe C, Patrinos ME, Tse A. Medically fragile children: An integrative review of the literature and recommendations for future research. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 2002;25(1):1–20. doi: 10.1080/014608602753504829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison TM. Family-centered pediatric nursing care: State of the science. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2010;25(5):335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Patient and Family-Centered Care. What are the core concepts of patient and family-centered care? 2010 Retrieved from http://www.ipfcc.org/faq.html.

- Jolley J, Shields L. The evolution of family-centered care. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2009;24(2):164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk S, Glendinning C, Callery P. Parent or nurse? The experience of being the parent of a technology-dependent child. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;51(5):456–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malusky SK. A concept analysis of family-centered care in the NICU. Neonatal Network. 2004;24(6):25–32. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.24.6.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meert KL, Clark J, Eggly S. Family-centered care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2013;60(3):761–772. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen G, Frederiksen K. Family-centered care of children in hospital-a concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2011;67(5):1152–1162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namachivayam P, Taylor A, Montague T, Moran K, Barrie J, Delzoppo C, Butt W. Long-stay children in intensive care: Long-term functional outcome and quality of life from a 20-yr institutional study. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2012;13(5):520–528. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31824fb989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price SL. Becoming a nurse: A meta-study of early professional socialization and career choice in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;65(1):11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray LD. Parenting and childhood chronicity: Making visible the invisible work. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2002;17(6):424–438. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2002.127172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves E, Timmons S, Dampier S. Parents’ experiences of negotiating care for their technology-dependent child. Journal of Child Health Care. 2006;10(3):228–239. doi: 10.1177/1367493506066483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm RS, Bradley JF. Normalization in families raising a child who is medically fragile/technology dependent and developmentally delayed. Qualitative Health Research. 2005a;15(6):807–820. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm RS, Bradley JF. The search for social safety and comfort in families raising children with complex chronic conditions. Journal of Family Nursing. 2005b;11(1):59–78. doi: 10.1177/1074840704272956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields L, Zhou H, Pratt J, Taylor M, Hunter J, Pascoe E. Family-centered care for hospitalised children aged 0–12 years. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;2012(10):Art. No.: CD004811. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004811.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava R, Stone B, Murphy N. Hospitalist care of the medically complex child. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2005;52(4):1165–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL. Continual permutations of action. New Brunswick, NJ: Aldine Transactions; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Uhl T, Fisher K, Docherty SL, Brandon DH. Insights into patient and family-centered care through the hospital experiences of parents. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2013;42:121–131. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. State and county quick facts: Los Angeles County, CA. 2014 [Data file]. Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/06/06037.html.

- Ward CR. The meaning of role strain. Advances in nursing science. 1986;8(2):39–49. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198601000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R, Chase SK, Mandle CL. Validity in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research. 2001;11(4):522–537. doi: 10.1177/104973201129119299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolosin R, Ayala L, Fulton BR. Nursing care, inpatient satisfaction, and value-based purchasing: Vital connections. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2012;42(6):321–325. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e318257392b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]