Abstract Abstract

Inhaled iloprost has proven to be an effective therapy in patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH). However, the acute hemodynamic effect of nebulized iloprost delivered via the I-neb Adaptive Aerosol Delivery (AAD) system remains unclear and needs to be assessed. In this study, 126 patients with PH were classified according to current guidelines (59, 34, 29, and 4 patients in groups 1/1′, 3, 4, and 5, respectively; 20 patients had idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension [iPAH]), were randomly assigned to inhale iloprost 2.5  g (n = 67) or 5.0

g (n = 67) or 5.0  g (n = 59) via the I-neb AAD system, and were assessed by right heart catheterization. In seven patients with iPAH, iloprost plasma levels were measured. The two iloprost doses caused decreases from baseline in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR; 2.5

g (n = 59) via the I-neb AAD system, and were assessed by right heart catheterization. In seven patients with iPAH, iloprost plasma levels were measured. The two iloprost doses caused decreases from baseline in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR; 2.5  g: –14.7%; 5.0

g: –14.7%; 5.0  g: –15.6%) and mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP; 2.5

g: –15.6%) and mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP; 2.5  g: –11.0%; 5.0

g: –11.0%; 5.0  g: –10.1%) while cardiac index (CI) increased (2.5

g: –10.1%) while cardiac index (CI) increased (2.5  g: +6.5%; 5.0

g: +6.5%; 5.0  g: +6.4%). The subset with iPAH also showed decreases from baseline in PVR and mPAP and an increase in CI. Peak iloprost plasma levels showed no significant difference after inhalation of 2.5

g: +6.4%). The subset with iPAH also showed decreases from baseline in PVR and mPAP and an increase in CI. Peak iloprost plasma levels showed no significant difference after inhalation of 2.5  g or 5.0

g or 5.0  g iloprost (95.5 pg/mL vs. 73.0 pg/mL; P = 0.06). In summary, nebulized iloprost delivered via the I-neb AAD system reduced mPAP and PVR and increased CI from baseline in a heterogeneous group of patients with PH and in the subset with iPAH. In patients with iPAH, inhalation of 2.5

g iloprost (95.5 pg/mL vs. 73.0 pg/mL; P = 0.06). In summary, nebulized iloprost delivered via the I-neb AAD system reduced mPAP and PVR and increased CI from baseline in a heterogeneous group of patients with PH and in the subset with iPAH. In patients with iPAH, inhalation of 2.5  g or 5.0

g or 5.0  g iloprost resulted in broadly similar peak iloprost plasma levels.

g iloprost resulted in broadly similar peak iloprost plasma levels.

Keywords: pulmonary arterial hypertension, inhaled iloprost, I-neb Adaptive Aerosol Delivery system

Introduction

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is characterized by elevated pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) due to remodeling of the pulmonary arteries, eventually leading to right heart failure.1 Current guidelines classify PH into the following categories: pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH; group 1), pulmonary veno-occlusive disease and/or pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis (group 1′), PH due to left heart disease (group 2), PH due to lung disease (LD) and/or hypoxia (group 3), chronic thromboembolic PH (CTEPH; group 4), and PH with unclear and/or multifactorial mechanisms (group 5).1 Specific therapies approved for patients with PAH comprise calcium channel blockers, endothelin receptor antagonists, phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, and prostanoids.2,3 Prostaglandin I2 (PGI2), produced mainly by pulmonary endothelial cells, mediates a major pathway in the pathophysiology of PAH.3 PGI2 acts as a vasodilator of pulmonary arteries and is also antithrombotic, antiproliferative, antimitogenic, and an immunomodulator.4 Reduced synthesis and imbalance of PGI2 and its metabolites in PAH eventually leads to vascular remodeling and vasoconstriction of the pulmonary arteries. Therefore PGI2 derivatives such as epoprostenol, iloprost, and treprostinil have been synthesized and are available for treatment.1,3 The unfavorable pharmacokinetic profile of epoprostenol, with its short half-life (<5 minutes), requires it to be delivered by continuous infusion via a central venous catheter connected to an infusion pump, the use of which is limited by the associated risk of local infections. Treprostinil has a longer half-life than epoprostenol and has been approved for subcutaneous and intravenous administration in the United States and Europe, although to date oral and inhaled treprostinil are still under investigation and are not approved in Europe.2 The subcutaneous application of treprostinil via an infusion pump improved exercise capacity and hemodynamic characteristics in a large heterogeneous group of patients with PH but unfortunately caused infusion site pain and even local infections.5 Therefore, inhaled iloprost administered via a nebulizer promises improved tolerability with a reduced adverse effect profile that consists mainly of cough, flushing, jaw pain, and headache. Several studies have investigated the safety and efficacy of nebulized iloprost, mostly involving patients with idiopathic PAH (iPAH), inoperable CTEPH, and PAH associated with collagen vascular diseases, and they have reported a significant improvement in hemodynamic parameters, symptoms, and exercise capacity.6-9

Since the introduction in 1997 of the first commercial nebulizer, the HaloLite Adaptive Aerosol Delivery (AAD) system, development and research have been performed to improve the design of the nebulizer. The current third-generation I-neb AAD system (Philips Respironics, Parsippany, NJ) is based on a vibrating mesh nebulizer coupled with the AAD technique. The I-neb AAD technology analyzes the patient’s breathing pattern, adjusting the delivered dose for each breath and generating both audible and visual feedback and therefore achieving precise dosing with minimal drug waste.10,11 The acute pulmonary hemodynamic response to inhaled iloprost nebulized by three different nebulizers (ILO-NEB/Aero-Trap [NEBU-TEC, Elsenfeld, Germany], Ventstream [MedicAid, Bognor Regis, United Kingdom], and HaloLite [Profile Therapeutics, Bognor Regis, United Kingdom] has been described in detail, but these results are not directly transferable to the current generation of nebulizers.12 The HaloLite system nebulized iloprost adjusted to the breathing pattern, but its filling volume was not standardized, and therefore precise dosing was difficult to calculate and there was significant wastage of drug.11,12 The ILO-NEB system continuously nebulized iloprost, and neither this nor Ventstream, a predecessor of HaloLite, adjusted to the patient’s breathing pattern.12 The aim of our study was therefore to determine the acute effects on the pulmonary circulation of nebulized iloprost via the I-neb AAD system in a large group of patients with PH.

Methods

Patients

We evaluated a cohort of patients with PH at the Giessen Pulmonary Hypertension Center (Department of Internal Medicine, Justus Liebig University Giessen, Universities of Giessen and Marburg Lung Center, Germany) during 2006 and 2007. Patients were randomized to treatment with inhaled iloprost 2.5  g or 5

g or 5  g via the I-neb AAD system. Patients were randomized in a 1∶1 ratio; those with systolic blood pressure ≤120 mmHg measured at enrolment were assigned to 2.5

g via the I-neb AAD system. Patients were randomized in a 1∶1 ratio; those with systolic blood pressure ≤120 mmHg measured at enrolment were assigned to 2.5  g iloprost.

g iloprost.

All patients received a diagnosis according to current guidelines and were included if the diagnosis of PH was confirmed by right heart catheter, on the basis of mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) ≥25 mmHg, pulmonary arterial wedge pressure (PAWP) <15 mmHg, and PVR  .1 Additionally, all included patients underwent a lung function test, and in randomly selected patients with iPAH, iloprost plasma levels were measured.

.1 Additionally, all included patients underwent a lung function test, and in randomly selected patients with iPAH, iloprost plasma levels were measured.

Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of group 2 PH, had worsening right heart function, had a worsening functional class, were not able to undergo right heart catheter testing, or were unable to inhale with the I-neb device. Patients receiving specific PAH therapies could enter the study without restrictions. Patients who were receiving background treatment with endothelin receptor antagonists or phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors had been receiving stable doses for at least 90 days.

Right heart catheter testing

All patients underwent right heart catheter testing 1 day after enrollment. A Swan-Ganz catheter was inserted under local anesthesia via the jugular vein. For 30 minutes after the insertion, baseline pressure values (PAP and central venous pressure [CVP]) were continuously assessed, while cardiac output (CO) was measured via thermodilution. PVR and cardiac index (CI) were calculated as described previously: PVR = (mPAP – PAWP)/CO; CI = (CO/body surface area).1 An inhalation of iloprost with the I-neb AAD system followed, which lasted until the system gave a vibratory signal at the end of nebulization. Pulmonary hemodynamics, systemic arterial blood pressure, mixed-venous oxygen saturation (SvO2), and arterial oxygen tension (PaO2) via blood gas analysis were assessed at baseline; the end of inhalation; and 5, 15, 30, 45, and 60 minutes after the end of inhalation.

Nebulizing device

The I-neb AAD system was used with standard AAD disks (2.5  g or 5.0

g or 5.0  g), operating in the tidal breathing mode. In this mode, the average length of the last three inhalations is used to predict the next inhalation. Aerosol is nebulized at the beginning of the fourth breath until after 50% of the predicted inhalation time has elapsed. Additionally, the I-neb AAD system gives a vibratory signal when nebulization of the predefined dose is complete.

g), operating in the tidal breathing mode. In this mode, the average length of the last three inhalations is used to predict the next inhalation. Aerosol is nebulized at the beginning of the fourth breath until after 50% of the predicted inhalation time has elapsed. Additionally, the I-neb AAD system gives a vibratory signal when nebulization of the predefined dose is complete.

Measurement of plasma iloprost levels

Plasma levels of iloprost were measured at baseline; at the end of the inhalation; and 5, 15, 30, 45, and 60 minutes after the end of inhalation. This measurement was performed using high-precision liquid chromatography-coupled mass spectrometry (Phenomenex, Perkin-Elmer, and Applied Biosystems).

Pulmonary function testing

Pulmonary function tests were performed according to current recommendations, and results were presented as percentages of predicted normal values according to European Respiratory Society guidelines (Masterscreen Body, ViaSys Healthcare, Germany).13

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or mean ± standard error of means (SEM) for normally distributed parameters and as median (interquartile range) for other parameters. The two-tailed t-test was used to test for differences between groups as appropriate. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 21.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

Patients

One hundred and twenty-six patients with PH (68 women and 58 men) presented with a mean age of 53.9 ± 15.8 years and a body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters) of 26.1 ± 5.7 (Table 1). Clinical classifications and specific PAH therapies are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and pulmonary function

| Parameter | All patients (n = 126) |

|---|---|

| No. of patients, male/female | 58/68 |

| Age (years) | 53.9 ± 15.8 |

| BMI | 26.1 ± 5.7 |

| WHO functional class (%) | |

| Class II | 16.1 |

| Class III | 61.3 |

| Class IV | 22.6 |

| Pulmonary function testing according to the etiology of diseases | |

| Group 1 and 1′ | |

| FEV1/VC (% predicted) | 95.5 ± 14 |

| TLC (% predicted) | 100.6 ± 17.2 |

| Group 3, COPD | |

| FEV1/VC (% predicted) | 62.7 ± 22.5 |

| TLC (% predicted) | 112.5 ± 18.2 |

| Group 3, interstitial lung disease | |

| FEV1/VC (% predicted) | 105.4 ± 16.2 |

| TLC (% predicted) | 68.4 ± 24.4 |

| Group 4 | |

| FEV1/VC (% predicted) | 99.3 ± 18.3 |

| TLC (% predicted) | 96.5 ± 16.1 |

| Group 5 | |

| FEV1/VC (% predicted) | 95.1 ± 19.9 |

| TLC (% predicted) | 99.3 ± 14.7 |

Data are mean ± standard deviation, unless otherwise indicated. BMI: body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; TLC: total lung capacity; VC: vital capacity; WHO: World Health Organization.

Table 2.

Etiology of disease and specific pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) treatment according to randomization

| Dose of inhaled iloprost | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | 2.5  g (n = 67) g (n = 67) |

5.0  g (n = 59) g (n = 59) |

| Group 1 (PAH) | ||

| Overall | 37 (55) | 22 (37) |

| Idiopathic | 8 (22) | 12 (55) |

| Heritable | 2 (5) | 1 (5) |

| Associated with PAH | ||

| Overall | 24 (65) | 8 (36) |

| Connective tissue diseases | 11 (46) | 4 (50) |

| Portal hypertension | 4 (17) | 3 (38) |

| HIV infection | 2 (8) | 1 (13) |

| Congenital heart disease | 7 (29) | 0 |

| Group 1′ (pulmonary veno-occlusive disease and/or pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis) | 3 (8) | 1 (5) |

| Group 3 (PH due to lung diseases) | 16 (24) | 18 (31) |

| COPD | 6 (38) | 10 (56) |

| Emphysema | 3 (50) | 7 (70) |

| CPFE | 0 | 2 (20) |

| Interstitial lung disease | 10 (63) | 8 (44) |

| IPF | 7 (70) | 5 (62.5) |

| EAA | 2 (20) | 2 (25) |

| NSIP | 1 (10) | 1 (12.5) |

| Group 4 (CTEPH) | 11 (16) | 18 (31) |

| Group 5 (others) | 3 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Pulmonary vasoactive therapies | ||

| Endothelin receptor antagonists | 10 (15) | 10 (17) |

| Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors | 47 (70) | 35 (59) |

Therapy

|

10 (15) | 14 (24) |

Data are no. (%) of patients. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPFE: combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema; CTEPH: chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; EAA: extrinsic allergic alveolitis; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; NSIP: nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Patients in the 2.5- g and 5.0-

g and 5.0- g dose groups were well matched in terms of severity of PH, with a high mPAP (P = 0.34), high mean PVR (P = 0.23), low CI (P = 0.5), and reduced SvO2 (P = 0.3); the majority of patients were in World Health Organization functional class III (Tables 1, 3). CVP at baseline for all patients was significantly higher in the 5.0-

g dose groups were well matched in terms of severity of PH, with a high mPAP (P = 0.34), high mean PVR (P = 0.23), low CI (P = 0.5), and reduced SvO2 (P = 0.3); the majority of patients were in World Health Organization functional class III (Tables 1, 3). CVP at baseline for all patients was significantly higher in the 5.0- g than the 2.5-

g than the 2.5- g dose group (P = 0.03); additionally, in patients with iPAH, associated PAH (aPAH), or CTEPH, the CVP at baseline was significantly higher in the 5.0-

g dose group (P = 0.03); additionally, in patients with iPAH, associated PAH (aPAH), or CTEPH, the CVP at baseline was significantly higher in the 5.0- g than the 2.5-

g than the 2.5- g dose group (Table 3). Lung function testing showed no significant obstructive or restrictive ventilatory abnormalities (expressed as mean total lung capacity [TLC] and forced expiratory volume in 1 s divided by vital capacity) in group 1/1′, 4, and 5 PH. Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exhibited a characteristic obstructive pattern, whereas patients with interstitial LD showed a substantial reduced TLC (Table 1). PaO2 levels were slightly reduced across all patient groups at baseline; for patients with CTEPH, PaO2 was significantly lower in the 5.0-

g dose group (Table 3). Lung function testing showed no significant obstructive or restrictive ventilatory abnormalities (expressed as mean total lung capacity [TLC] and forced expiratory volume in 1 s divided by vital capacity) in group 1/1′, 4, and 5 PH. Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exhibited a characteristic obstructive pattern, whereas patients with interstitial LD showed a substantial reduced TLC (Table 1). PaO2 levels were slightly reduced across all patient groups at baseline; for patients with CTEPH, PaO2 was significantly lower in the 5.0- g dose than the 2.5-

g dose than the 2.5- g dose group (Table 4). Mean systemic arterial blood pressures (MAPs) at baseline were significantly higher in the 5.0-

g dose group (Table 4). Mean systemic arterial blood pressures (MAPs) at baseline were significantly higher in the 5.0- g dose than the 2.5-

g dose than the 2.5- g dose groups across all patients.

g dose groups across all patients.

Table 3.

Acute hemodynamic effects of inhaled iloprost delivered via the I-neb Adaptive Aerosol Delivery system according to clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension

| CI | CVP | mPAP | PVR | SvO2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Etiology, dose,  g g |

No. of patients | Baseline, L/min/m2 | Maximum change from baseline, % | Baseline, mmHg | Maximum change from baseline, % | Baseline, mmHg | Maximum change from baseline, % | Baseline,

|

Maximum change from baseline, % | Baseline, % | Maximum change from baseline, % |

| All | |||||||||||

| 2.5 | 67 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | +6.5 ± 2.2 | 5.3 ± 0.6 | −23.8 ± 8.8 | 47.6 ± 1.9 | −11.0 ± 1.3 | 831.4 ± 52.9 | −14.7 ± 2.5 | 64.5 ± 2.7 | +1.9 ± 2.7 |

| 5.0 | 59 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | +6.4 ± 2.2 | 6.5 ± 0.7a | −23.9 ± 8.2 | 46.8 ± 2.0 | −10.1 ± 1.5 | 791.0 ± 57.4 | −15.6 ± 2.4 | 63.2 ± 3 | +4.8 ± 2.3 |

| iPAH | |||||||||||

| 2.5 | 8 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | +4.6 ± 7.2 | 4.9 ± 1.7 | −33.3 ± 25.7 | 55.4 ± 4.3 | −12.7 ± 5.0 | 1189.4 ± 158.2 | −12.7 ± 8.1 | 63.2 ± 1.9 | +4.9 ± 2.2 |

| 5.0 | 12 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | +11.2 ± 7.6 | 10.6 ± 2.6b | −38.4 ± 8.0 | 55.4 ± 6.4 | −9.7 ± 4.4 | 1032.9 ± 111.3 | −16.5 ± 8.8 | 58.6 ± 3.5 | +7.3 ± 2.8 |

| aPAH | |||||||||||

| 2.5 | 24 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | +10.3 ± 3.3 | 4.8 ± 0.7 | −28.1 ± 12.6 | 51.8 ± 2.4 | −11.3 ± 1.6 | 949.8 ± 65.3 | −17.7 ± 3.0 | 65.1 ± 2 | +1.5 ± 2.2 |

| 5.0 | 8 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | +7.6 ± 3.8 | 8.2 ± 1.4c | −50.3 ± 11.7 | 54.5 ± 3.8 | −9.7 ± 2.8 | 915.1 ± 79.5 | −15.7 ± 4.8 | 61.5 ± 6.8 | +1.1 ± 3.8 |

| CTEPH | |||||||||||

| 2.5 | 11 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | +1.8 ± 3.2 | 7.6 ± 1.4 | −33.7 ± 7.9 | 40.1 ± 2.8 | −10.1 ± 2.2 | 731.3 ± 105.7 | −16.2 ± 3.6 | 61.4 ± 1.9 | +2.5 ± 1.8 |

| 5.0 | 18 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | +9.0 ± 3.9 | 5.2 ± 1.0d | −36.6 ± 10.1 | 45.4 ± 2.6e | −9.8 ± 2.4 | 897.1 ± 123.5 | −17.1 ± 3.7 | 61.8 ± 1.7 | +5.5 ± 1.7 |

| LD | |||||||||||

| 2.5 | 16 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | +0.6 ± 2.8 | 5.0 ± 1.4 | −37.2 ± 21.9 | 39.2 ± 3.6 | −10.5 ± 4.1 | 523.2 ± 91.7 | −4.5 ± 6.4 | 66.9 ± 2.3 | −1.8 ± 1.5 |

| 5.0 | 18 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | +2.4 ± 3.4 | 5.8 ± 1.2 | −28.4 ± 18.8 | 40.9 ± 2.1 | −12.4 ± 2.9 | 555.8 ± 56.0 | −14.9 ± 3.6f | 65.3 ± 1.2 | +1.5 ± 1.3 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of means, unless otherwise indicated. No significant differences between groups in maximum change from baseline. aPAH: associated pulmonary arterial hypertension; CI: cardiac index, CTEPH: chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; CVP: central venous pressure; iPAH: idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension; LD: lung disease; mPAP: mean pulmonary arterial pressure; PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance; SvO2: mixed-venous oxygen saturation.

P = 0.034.

P = 0.09.

P = 0.001.

P = 0.029.

P = 0.031.

P = 0.048.

Table 4.

Acute effects on PaO2 and systemic blood pressure of inhaled iloprost delivered via the I-neb Adaptive Aerosol Delivery system according to clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension

| PaO2 | Mean systemic blood pressure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Etiology, dose,  g g |

No. of patients | Baseline, mmHg | Maximum change from baseline, mmHg | Baseline, mmHg | Maximum change from baseline, mmHg |

| All | |||||

| 2.5 | 67 | 72 ± 3.3 | 68.7 ± 2.5 | 82.8 ± 1.4 | 77.2 ± 1.5b |

| 5.0 | 59 | 69.1 ± 3.5 | 65 ± 2.4 | 92.1 ± 1.8a | 86.3 ± 1.8b |

| iPAH | |||||

| 2.5 | 8 | 73.7 ± 4.4 | 70.6 ± 4.5 | 80.6 ± 2.4 | 74.9 ± 2.3b |

| 5.0 | 12 | 69.5 ± 2.5 | 67.9 ± 3.3 | 91.6 ± 5.3a | 84.4 ± 4.7b |

| aPAH | |||||

| 2.5 | 24 | 70.5 ± 2 | 68.8 ± 3 | 83.3 ± 2.8 | 74.8 ± 3b |

| 5.0 | 8 | 67.9 ± 1.8 | 61.3 ± 2.3 | 90.3 ± 4.8a | 82.9 ± 3.5c |

| CTEPH | |||||

| 2.5 | 11 | 74.5 ± 3.6 | 68.8 ± 2.6 | 76.8 ± 2.6 | 74.3 ± 3 |

| 5.0 | 18 | 64.8 ± 1.6a | 59.8 ± 3.3 | 92.2 ± 2.3a | 86.3 ± 3d |

| LD | |||||

| 2.5 | 16 | 68.6 ± 2.8 | 64.3 ± 3.2 | 86.1 ± 2.3 | 83.5 ± 1.8 |

| 5.0 | 18 | 74.8 ± 4.4 | 68 ± 3.3 | 94.1 ± 3.2a | 90.7 ± 2.7 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of means, unless otherwise indicated. No significant differences between groups in maximum change from baseline. aPAH: associated pulmonary arterial hypertension; CTEPH: chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; iPAH: idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension; LD: lung disease; PaO2: arterial oxygen tension.

P = 0.001 versus 2.5- g dose group at baseline.

g dose group at baseline.

P = 0.001 versus baseline.

P = 0.02 versus baseline.

P = 0.006 versus baseline.

Acute hemodynamic effects

Patients were analyzed according to the clinical classification (Table 3). For all classifications of PH, patients in both the 2.5- g dose and 5.0-

g dose and 5.0- g dose groups showed a decrease from baseline in mean PVR, mPAP, and CVP, whereas CI increased; the maximum changes showed no significant differences between the dose groups. SvO2 increased insignificantly across all patients groups, with the exception of the decrease in SvO2 in the 2.5-

g dose groups showed a decrease from baseline in mean PVR, mPAP, and CVP, whereas CI increased; the maximum changes showed no significant differences between the dose groups. SvO2 increased insignificantly across all patients groups, with the exception of the decrease in SvO2 in the 2.5- g dose group of patients with LD; this decrease was also not significant.

g dose group of patients with LD; this decrease was also not significant.

PaO2 decreased slightly across all groups. The reduction of PaO2 was more pronounced, albeit not significant, in the groups of CTEPH, LD, and 5- g dose aPAH patients. In addition, MAP decreased across all patient groups (Table 4).

g dose aPAH patients. In addition, MAP decreased across all patient groups (Table 4).

In the iPAH clinical classification group, the 5.0- g dose group demonstrated a slightly (but not significantly) greater maximum decrease from baseline in mean PVR than did the 2.5-

g dose group demonstrated a slightly (but not significantly) greater maximum decrease from baseline in mean PVR than did the 2.5- g group (–16.5% ± 8.8% vs. –12.7% ± 8.1%, respectively; P = 0.66) and a nonsignificantly greater increase in CI (+11.2% ± 7.6% vs. +4.6% ± 7.2%; P = 0.39). The maximum changes from baseline in mPAP and CVP showed no significant differences between the 2.5-

g group (–16.5% ± 8.8% vs. –12.7% ± 8.1%, respectively; P = 0.66) and a nonsignificantly greater increase in CI (+11.2% ± 7.6% vs. +4.6% ± 7.2%; P = 0.39). The maximum changes from baseline in mPAP and CVP showed no significant differences between the 2.5- g dose and 5.0-

g dose and 5.0- g dose groups in patients with iPAH.

g dose groups in patients with iPAH.

In the aPAH clinical classification group, both the 2.5- g dose and 5-

g dose and 5- g dose groups showed a decrease from baseline in mean PVR, mPAP, and CVP, whereas CI increased. The maximum changes from baseline showed no significant differences between the 2.5-

g dose groups showed a decrease from baseline in mean PVR, mPAP, and CVP, whereas CI increased. The maximum changes from baseline showed no significant differences between the 2.5- g dose and 5.0-

g dose and 5.0- g dose groups.

g dose groups.

The CTEPH clinical classification group demonstrated a decrease from baseline in mean PVR, mPAP, and CVP in both dose groups. CI increased to a greater extent in the 5.0- g group than the 2.5-

g group than the 2.5- g group, but this difference was not statistically significant (+9.0% ± 3.9% vs. +1.8% ± 3.2%; P = 0.054).

g group, but this difference was not statistically significant (+9.0% ± 3.9% vs. +1.8% ± 3.2%; P = 0.054).

In LD-PH, the 2.5- g dose and 5.0-

g dose and 5.0- g dose groups showed a decrease from baseline in mPAP and in CVP, whereas CI increased only slightly in both groups. The 5.0-

g dose groups showed a decrease from baseline in mPAP and in CVP, whereas CI increased only slightly in both groups. The 5.0- g dose group demonstrated a significantly larger maximum decrease from baseline in mean PVR than the 2.5-

g dose group demonstrated a significantly larger maximum decrease from baseline in mean PVR than the 2.5- g dose group (–14.9% ± 3.6% vs. –4.5% ± 6.4%; P = 0.048).

g dose group (–14.9% ± 3.6% vs. –4.5% ± 6.4%; P = 0.048).

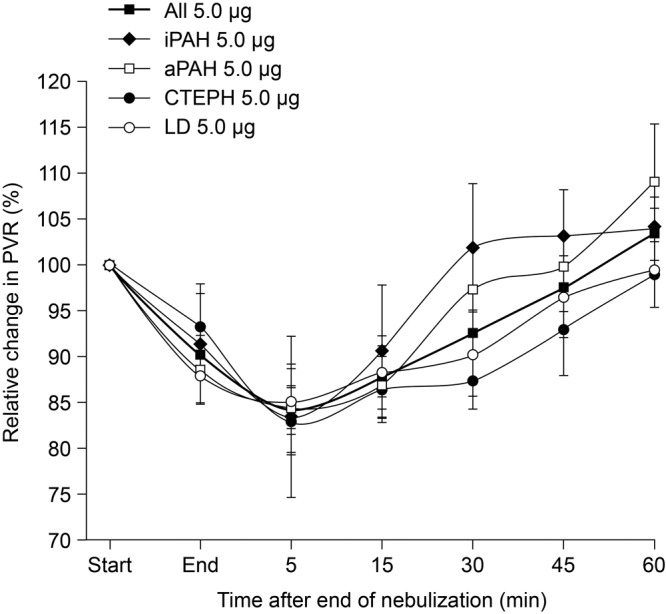

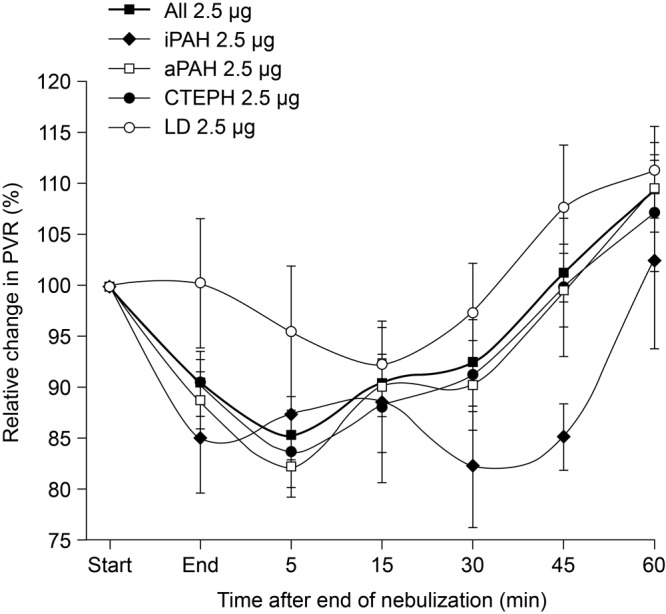

The nebulization of 2.5  g and 5.0

g and 5.0  g iloprost in patients with iPAH, aPAH, and CTEPH caused an immediate effect on PVR: a maximum decrease from baseline was observed within 5 minutes of the end of inhalation, except in patients with iPAH receiving 2.5

g iloprost in patients with iPAH, aPAH, and CTEPH caused an immediate effect on PVR: a maximum decrease from baseline was observed within 5 minutes of the end of inhalation, except in patients with iPAH receiving 2.5  g iloprost, who had a maximum decrease from baseline within 35 minutes of the end of inhalation (Figs. 1, 2). Patients with LD exhibited the maximum decrease in PVR at 15 minutes after the end of inhalation in the 2.5-

g iloprost, who had a maximum decrease from baseline within 35 minutes of the end of inhalation (Figs. 1, 2). Patients with LD exhibited the maximum decrease in PVR at 15 minutes after the end of inhalation in the 2.5- g dose group, whereas nebulization of 5.0

g dose group, whereas nebulization of 5.0  g iloprost led to a maximum decrease in PVR after 5 minutes (Fig. 2).

g iloprost led to a maximum decrease in PVR after 5 minutes (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Relative change in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) after inhalation of 5.0  g iloprost via the I-neb Adaptive Aerosol Delivery system: comparison of etiologies. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of means. aPAH: associated pulmonary arterial hypertension; CTEPH: chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; iPAH: idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension; LD: lung diseases.

g iloprost via the I-neb Adaptive Aerosol Delivery system: comparison of etiologies. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of means. aPAH: associated pulmonary arterial hypertension; CTEPH: chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; iPAH: idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension; LD: lung diseases.

Figure 2.

Relative change in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) after inhalation of 2.5  g iloprost via the I-neb Adaptive Aerosol Delivery system: comparison of etiologies. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of means. aPAH: associated pulmonary arterial hypertension; CTEPH: chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; iPAH: idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension; LD: lung disease.

g iloprost via the I-neb Adaptive Aerosol Delivery system: comparison of etiologies. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of means. aPAH: associated pulmonary arterial hypertension; CTEPH: chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; iPAH: idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension; LD: lung disease.

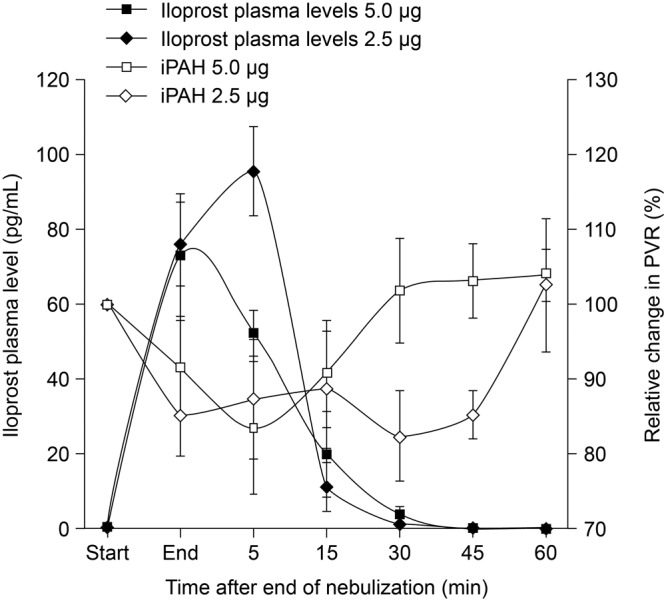

In the iPAH clinical classification group, iloprost plasma levels reached a maximum within 5 minutes of the end of inhalation irrespective of the nebulized dose (2.5- g dose group: 95.5 ± 11.8 pg/mL; 5.0-

g dose group: 95.5 ± 11.8 pg/mL; 5.0- g dose group: 73.0 ± 16.7 pg/mL; n = 7; P = 0.06). As shown in Figure 3, the maximum iloprost plasma levels corresponded with the maximum decrease in PVR, whereas beyond 45 minutes after the end of inhalation, iloprost plasma levels were no longer detectable and PVR was increasing (Fig. 3).

g dose group: 73.0 ± 16.7 pg/mL; n = 7; P = 0.06). As shown in Figure 3, the maximum iloprost plasma levels corresponded with the maximum decrease in PVR, whereas beyond 45 minutes after the end of inhalation, iloprost plasma levels were no longer detectable and PVR was increasing (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Relative change in iloprost plasma levels and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) after inhalation of 2.5  g and 5.0

g and 5.0  g iloprost via the I-neb Adaptive Aerosol Delivery system in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (iPAH; n = 7). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of means.

g iloprost via the I-neb Adaptive Aerosol Delivery system in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (iPAH; n = 7). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of means.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the acute hemodynamic effects of nebulized iloprost via the I-neb AAD system in a large heterogeneous group of patients with PH, randomized to 2.5 μg or 5.0 μg iloprost. The analyzed study group consisted of patients with iPAH, aPAH, CTEPH, or LD. Despite the different and unequal distribution of etiologies between the 2.5- g dose and 5.0-

g dose and 5.0- g dose groups, both groups exhibited significant pulmonary vasodilatation with a decrease of mPAP and PVR within 5 minutes after the end of inhalation. In the 5.0-

g dose groups, both groups exhibited significant pulmonary vasodilatation with a decrease of mPAP and PVR within 5 minutes after the end of inhalation. In the 5.0- g group, CI immediately improved considerably in patients with iPAH, aPAH, and CTEPH, although not in LD-PH. Overall, patients in the 2.5-μg dose group demonstrated a comparable, although less intense, acute pulmonary vasodilatation with a decrease in mPAP and PVR and an improvement in CI. Interestingly, CVP, as a marker of fluid overloading of the right ventricle and of the severity of underlying disease, was significantly higher at baseline in the 5.0-

g group, CI immediately improved considerably in patients with iPAH, aPAH, and CTEPH, although not in LD-PH. Overall, patients in the 2.5-μg dose group demonstrated a comparable, although less intense, acute pulmonary vasodilatation with a decrease in mPAP and PVR and an improvement in CI. Interestingly, CVP, as a marker of fluid overloading of the right ventricle and of the severity of underlying disease, was significantly higher at baseline in the 5.0- g dose group of patients with iPAH, aPAH, and CTEPH. Although the maximum decrease in CVP was more pronounced in the 5.0-

g dose group of patients with iPAH, aPAH, and CTEPH. Although the maximum decrease in CVP was more pronounced in the 5.0- g dose group, no statistical difference was seen between this and the 2.5-

g dose group, no statistical difference was seen between this and the 2.5- g dose group; however, the demonstrated ability of inhaled iloprost to significantly reduce CVP is in line with already published data.7 Although MAP decreased across all study groups, clinically relevant reductions in MAP were not observed. However, the pattern of MAP throughout inhalation of iloprost is limited by the study design, whereby patients with initial systolic blood pressure ≤120 mmHg were assigned per protocol to 2.5

g dose group; however, the demonstrated ability of inhaled iloprost to significantly reduce CVP is in line with already published data.7 Although MAP decreased across all study groups, clinically relevant reductions in MAP were not observed. However, the pattern of MAP throughout inhalation of iloprost is limited by the study design, whereby patients with initial systolic blood pressure ≤120 mmHg were assigned per protocol to 2.5  g iloprost.

g iloprost.

Our study therefore indicates for the first time, to our knowledge, that the acute hemodynamic response to iloprost delivered using the I-neb AAD system is in line with that seen in already published data using older-generation nebulizers.11,12,14 Olschewski et al.12 described a similar, immediate response of mPAP, CI, and PVR within 5 minutes after the end of inhalation (5.0  g iloprost) while using first-generation nebulizers in patients with PAH. The second-generation device (the Prodose AAD system [Philips Respironics, Respiratory Drug Delivery, Chichester, United Kingdom]), which was most comparable to the I-neb AAD device, was used in a trial that investigated iloprost in combination therapy and showed improved pulmonary hemodynamics in patients with iPAH and aPAH over a 12-week period.11,14 Only one small study has used the current I-neb AAD system.15 Martischnig et al.15 evaluated the acute hemodynamic effects of inhaled iloprost in a heterogeneous group of patients with PAH that included those with aPAH and iPAH (n = 7) in a critical care unit. They described a significant decrease in PVR with improved CI in patients with PAH with acute right heart failure, and so their data are not fully transferable to clinically stable patients with PH with chronic right heart failure.15 However, the overall similar acute hemodynamic response of the different generations of AAD systems is not surprising, given that in vitro data suggest comparable aerosol characteristics and inhaled mass with the different devices.16

g iloprost) while using first-generation nebulizers in patients with PAH. The second-generation device (the Prodose AAD system [Philips Respironics, Respiratory Drug Delivery, Chichester, United Kingdom]), which was most comparable to the I-neb AAD device, was used in a trial that investigated iloprost in combination therapy and showed improved pulmonary hemodynamics in patients with iPAH and aPAH over a 12-week period.11,14 Only one small study has used the current I-neb AAD system.15 Martischnig et al.15 evaluated the acute hemodynamic effects of inhaled iloprost in a heterogeneous group of patients with PAH that included those with aPAH and iPAH (n = 7) in a critical care unit. They described a significant decrease in PVR with improved CI in patients with PAH with acute right heart failure, and so their data are not fully transferable to clinically stable patients with PH with chronic right heart failure.15 However, the overall similar acute hemodynamic response of the different generations of AAD systems is not surprising, given that in vitro data suggest comparable aerosol characteristics and inhaled mass with the different devices.16

Despite the nebulizer used, the acute hemodynamic response within the different PH etiologies in our study is comparable to already published data.8,9,17-20 In detail, patients with iPAH, aPAH, or CTEPH who received 10.0  g of inhaled iloprost showed an increase in exercise capacity and an improvement in symptoms and pulmonary hemodynamics over a 12-week period.6 Krug et al.9 assessed the acute hemodynamic effects of 5.0

g of inhaled iloprost showed an increase in exercise capacity and an improvement in symptoms and pulmonary hemodynamics over a 12-week period.6 Krug et al.9 assessed the acute hemodynamic effects of 5.0  g inhaled iloprost administered with an ILO-NEB or OPTINEB nebulizer (NEBU-TEC, Elsenfeld, Germany) in 20 patients with CTEPH and found a maximum decrease in PVR of at least 15% with a simultaneous decrease of mPAP and increase of CI. Furthermore, the acute hemodynamic effects of nebulized PGI2 in patients with PH due to ILD were described in eight patients using a jet nebulization with a high total dose (54–68

g inhaled iloprost administered with an ILO-NEB or OPTINEB nebulizer (NEBU-TEC, Elsenfeld, Germany) in 20 patients with CTEPH and found a maximum decrease in PVR of at least 15% with a simultaneous decrease of mPAP and increase of CI. Furthermore, the acute hemodynamic effects of nebulized PGI2 in patients with PH due to ILD were described in eight patients using a jet nebulization with a high total dose (54–68  g) resulting in a decrease in mPAP and PVR and an increase in CO.17

g) resulting in a decrease in mPAP and PVR and an increase in CO.17

Interestingly, our heterogeneous group of patients with COPD and ILD presented with increased PVR and mPAP, displaying significant PH, but with almost normal CI. The inhalation of iloprost reduced PVR and mPAP, but CI and SvO2 remained almost unaffected. Despite the fact that both patients with CTEPH and LD-PH were exposed to inhaled iloprost knowing that they are prone to develop gas exchange disturbances upon administration of vasodilators, we do not observe significant impairment of oxygenation in our study. These data corroborate our previous observation of a comparative vasodilator challenge in patients with severe ILD plus concomitant PH.17 In that study, elaborate assessment of gas exchange properties by means of blood gas analysis and multiple inert gas elimination technique were performed, respectively. The concept of pulmonary and intrapulmonary selectivity of inhaled vasodilators, namely inhaled nitric oxid and inhaled prostacyclin, was demonstrated for the first time in this complex disease entity.

Although intravenous prostacyclin, short-acting calcium channel blockers, and inhaled vasodilators induced equipotent reduction in PVR, only the inhaled vasodilators reduced PVR significantly stronger than systemic vascular resistance (reflective of pulmonary selectivity) and maintained gas exchange (reflective of intrapulmonary selective vasodilation).17 Although we observed numerically a tendency toward more pronounced reduction in PaO2 in the LD-PH patient population, as compared with the iPAH subgroup, significant deteriorations were observed in neither of the groups in our study. Nonetheless, as we also described a trend toward a dose effect relationship with regard to deteriorations in gas exchange, this might be attributable to spill-over effects of high-dose inhalative iloprost with subsequent gradual loss of pulmonary selectivity. Because head-to-head comparison of both studies is not possible in retrospect, we can only speculate that the more pronounced gas exchange disturbances reported by Boeck et al.21 may be attributable to significantly higher dosages of iloprost in that study. Furthermore, Boeck et al.21 included a high number of patients who already were dependent on long-term oxygen therapy, and it is probable that discontinuation of oxygen therapy throughout inhalation contributed to the reduction in PaO2. Additionally, the timing of the PaO2 sampling with respect to peak or trough levels was not exactly defined.21 However, there is no evidence for routine use of inhaled iloprost in patients with CTEPH or LD-PH, even in cases of “out of proportion” PH, and evidence regarding its application in these patients is limited to case studies.1,17,22,23

In patients with iPAH, the dose-dependent reduction of PVR with enhancement of CI and the corresponding iloprost plasma levels are in line with already-published data, underlining the efficacy of inhaled iloprost despite different forms of application.12 The maximum plasma iloprost levels found in our cohort were lower than those recorded by Olschewski et al.12 due to the different radioimmunoassay used in our study, with a lower threshold value. Additionally, inhalation of 2.5  g and 5.0

g and 5.0  g nebulized iloprost resulted in almost similar peak iloprost plasma levels, probably because of the small sample size (n = 7). However, inhaled doses of 2.5

g nebulized iloprost resulted in almost similar peak iloprost plasma levels, probably because of the small sample size (n = 7). However, inhaled doses of 2.5  g and 5.0

g and 5.0  g iloprost were not associated with statistically different acute hemodynamic responses, although the decrease in mPAP and PVR and the increase in CI were more marked in the 5.0-

g iloprost were not associated with statistically different acute hemodynamic responses, although the decrease in mPAP and PVR and the increase in CI were more marked in the 5.0- g dose group.

g dose group.

What does this observation add to our understanding of treatment with inhaled iloprost in PH? The acute hemodynamic response to nebulized iloprost via the I-neb AAD system in patients with iPAH, aPAH, CTEPH, and LD is immediate, comparable to the older generations of nebulizers. The measured iloprost plasma levels in patients with iPAH indicate a rapid systemic circulation with subsequent disappearance after approximately 30 minutes. This finding is in line with the published data from Olschewski et al.,12 also indicating a rapid alveolar delivery by nebulization, causing a prolonged local vasodilatation not reflected by iloprost plasma levels. In contrast to the older generations of nebulizers, the ability of the I-neb AAD system to nebulize iloprost depending on the patient’s breathing pattern minimizes drug wastage and application of the drug into the alveolar dead space. Furthermore, the system generates precise dosing and various feedback signals that lead to improved acceptance by the patient.

Limitations of the study were the heterogeneous study group, the small sample size of plasma iloprost measurements, and unequal distribution of etiologies. In this single-center study, a selection bias as revealed by the overall good hemodynamic response to inhaled iloprost in our study group cannot be excluded.

In conclusion, this is the first study to evaluate the acute hemodynamic response to iloprost administered via the I-neb AAD system in patients with PH. Despite the different etiologies and severities of underlying disease, patients in both dose groups (2.5  g and 5.0

g and 5.0  g) exhibited a significant pulmonary vasodilatation while CI improved, comparable to results obtained with older nebulizers. In patients with iPAH, the 5.0-

g) exhibited a significant pulmonary vasodilatation while CI improved, comparable to results obtained with older nebulizers. In patients with iPAH, the 5.0- g dose resulted in a slightly larger decrease in PVR with a more enhanced CI than the 2.5-

g dose resulted in a slightly larger decrease in PVR with a more enhanced CI than the 2.5- g dose at broadly similar peak iloprost plasma levels.

g dose at broadly similar peak iloprost plasma levels.

Source of Support: This study was supported by a research grant from Bayer.

Conflict of Interest: MJR reports nonfinancial support from Bayer Healthcare. HAG has received support from Actelion, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer. RV has received support from Actelion and Pfizer. WS has received speaker fees from Pfizer and Bayer HealthCare and is a consultant for Bayer Pharma. HG has received support and/or honoraria from Actelion, AstraZeneca, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Cilag, Lilly, Pfizer, and United Therapeutics/Open Monoclonal Technology. All other authors: none declared.

References

- 1.Galiè N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), endorsed by the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J 2009;30(20):2493–2537. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Seferian A, Simonneau G. Therapies for pulmonary arterial hypertension: where are we today, where do we go tomorrow? Eur Respir Rev 2013;22(129):217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Humbert M, Sitbon O, Simonneau G. Treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2004;351(14):1425–1436. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Krug S, Sablotzki A, Hammerschmidt S, Wirtz H, Seyfarth HJ. Inhaled iloprost for the control of pulmonary hypertension. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2009;5(1):465–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Simonneau G, Barst RJ, Galiè N, et al. Continuous subcutaneous infusion of treprostinil, a prostacyclin analogue, in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165(6):800–804. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Olschewski H, Simonneau G, Galiè N, et al. Inhaled iloprost for severe pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med 2002;347(5):322–329. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Opitz CF, Wensel R, Winkler J, et al. Clinical efficacy and survival with first-line inhaled iloprost therapy in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir Rev 2005;26(18):1895–1902. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Kramm T, Eberle B, Guth S, Mayer E. Inhaled iloprost to control residual pulmonary hypertension following pulmonary endarterectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2005;28(6):882–888. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Krug S, Hammerschmidt S, Pankau H, Wirtz H, Seyfarth HJ. Acute improved hemodynamics following inhaled iloprost in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Respiration 2008;76(2):154–159. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Dhand R. Intelligent nebulizers in the age of the internet: the I-neb Adaptive Aerosol Delivery (AAD) system. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 2010;23(suppl 1):iii–v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Denyer J, Dyche T. The Adaptive Aerosol Delivery (AAD) technology: past, present, and future. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 2010;23(suppl 1):S1–S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Olschewski H, Rohde B, Behr J, et al. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of inhaled iloprost, aerosolized by three different devices, in severe pulmonary hypertension. Chest 2003;124(4):1294–1304. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Quanjer PH, Tammeling GJ, Cotes JE, Pedersen OF, Peslin R, Yernault JC. Lung volumes and forced ventilatory flows. Report Working Party Standardization of Lung Function Tests, European Community for Steel and Coal. Official Statement of the European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J Suppl 1993;16:5–40. [PubMed]

- 14.McLaughlin VV, Oudiz RJ, Frost A, et al. Randomized study of adding inhaled iloprost to existing bosentan in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174(11):1257–1263. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Martischnig AM, Tichy A, Nikfardjam M, Heinz G, Lang IM, Bonderman D. Inhaled iloprost for patients with precapillary pulmonary hypertension and right-side heart failure. J Cardiac Fail 2011;17(10):813–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Van Dyke RE, Nikander K. Delivery of iloprost inhalation solution with the HaloLite, Prodose, and I-neb Adaptive Aerosol Delivery systems: an in vitro study. Respir Care 2007;52(2):184–190. [PubMed]

- 17.Olschewski H, Ghofrani HA, Walmrath D, et al. Inhaled prostacyclin and iloprost in severe pulmonary hypertension secondary to lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160(2):600–607. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Wensel R, Opitz CF, Ewert R, Bruch L, Kleber FX. Effects of iloprost inhalation on exercise capacity and ventilatory efficiency in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 2000;101(20):2388–2392. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Blumberg FC, Riegger GA, Pfeifer M. Hemodynamic effects of aerosolized iloprost in pulmonary hypertension at rest and during exercise. Chest 2002;121(5):1566–1571. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Hoeper MM, Olschewski H, Ghofrani HA, et al. A comparison of the acute hemodynamic effects of inhaled nitric oxide and aerosolized iloprost in primary pulmonary hypertension. German PPH study group. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35(1):176–182. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Boeck L, Tamm M, Grendelmeier P, Stolz D. Acute effects of aerosolized iloprost in COPD related pulmonary hypertension: a randomized controlled crossover trial. PloS ONE 2012;7(12):e52248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Lasota B, Skoczynski S, Mizia-Stec K, Pierzchala W. The use of iloprost in the treatment of ‘out of proportion’ pulmonary hypertension in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Clin Pharm 2013;35(3):313–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Kramm T, Eberle B, Krummenauer F, Guth S, Oelert H, Mayer E. Inhaled iloprost in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: effects before and after pulmonary thromboendarterectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;76(3):711–718. [DOI] [PubMed]