Abstract

Previous models of O2 transport and utilization in health considered diffusive exchange of O2 in lung and muscle, but, reasonably, neglected functional heterogeneities in these tissues. However, in disease, disregarding such heterogeneities would not be justified. Here, pulmonary ventilation–perfusion and skeletal muscle metabolism–perfusion mismatching were added to a prior model of only diffusive exchange. Previously ignored O2 exchange in non-exercising tissues was also included. We simulated maximal exercise in (a) healthy subjects at sea level and altitude, and (b) COPD patients at sea level, to assess the separate and combined effects of pulmonary and peripheral functional heterogeneities on overall muscle O2 uptake ( and on mitochondrial

and on mitochondrial  (

( ). In healthy subjects at maximal exercise, the combined effects of pulmonary and peripheral heterogeneities reduced arterial

). In healthy subjects at maximal exercise, the combined effects of pulmonary and peripheral heterogeneities reduced arterial  (

( ) at sea level by 32 mmHg, but muscle

) at sea level by 32 mmHg, but muscle  by only 122 ml min−1 (–3.5%). At the altitude of Mt Everest, lung and tissue heterogeneity together reduced

by only 122 ml min−1 (–3.5%). At the altitude of Mt Everest, lung and tissue heterogeneity together reduced  by less than 1 mmHg and

by less than 1 mmHg and  by 32 ml min−1 (–2.4%). Skeletal muscle heterogeneity led to a wide range of potential

by 32 ml min−1 (–2.4%). Skeletal muscle heterogeneity led to a wide range of potential  among muscle regions, a range that becomes narrower as

among muscle regions, a range that becomes narrower as increases, and in regions with a low ratio of metabolic capacity to blood flow,

increases, and in regions with a low ratio of metabolic capacity to blood flow,  can exceed that of mixed muscle venous blood. For patients with severe COPD, peak

can exceed that of mixed muscle venous blood. For patients with severe COPD, peak  was insensitive to substantial changes in the mitochondrial characteristics for O2 consumption or the extent of muscle heterogeneity. This integrative computational model of O2 transport and utilization offers the potential for estimating profiles of

was insensitive to substantial changes in the mitochondrial characteristics for O2 consumption or the extent of muscle heterogeneity. This integrative computational model of O2 transport and utilization offers the potential for estimating profiles of  both in health and in diseases such as COPD if the extent for both lung ventilation–perfusion and tissue metabolism–perfusion heterogeneity is known.

both in health and in diseases such as COPD if the extent for both lung ventilation–perfusion and tissue metabolism–perfusion heterogeneity is known.

Key points

We expanded a prior model of whole-body O2 transport and utilization based on diffusive O2 exchange in the lungs and tissues to additionally allow for both lung ventilation–perfusion and tissue metabolism–perfusion heterogeneities, in order to estimate

and mitochondrial

and mitochondrial  (

( ) during maximal exercise.

) during maximal exercise.Simulations were performed using data from (a) healthy fit subjects exercising at sea level and at altitudes up to the equivalent of Mount Everest and (b) patients with mild and severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exercising at sea level.

Heterogeneity in skeletal muscle may affect maximal O2 availability more than heterogeneity in lung, especially if mitochondrial metabolic capacity (

) is only slightly higher than the potential to deliver O2, but when

) is only slightly higher than the potential to deliver O2, but when  is substantially higher than O2 delivery, the effect of muscle heterogeneity is comparable to that of lung heterogeneity.

is substantially higher than O2 delivery, the effect of muscle heterogeneity is comparable to that of lung heterogeneity.Skeletal muscle heterogeneity may result in a wide range of potential mitochondrial PO2 values, a range that becomes narrower as

increases; in regions with a low ratio of metabolic capacity to blood flow,

increases; in regions with a low ratio of metabolic capacity to blood flow,  can exceed that of mixed muscle venous blood.

can exceed that of mixed muscle venous blood.The combined effects of lung and peripheral heterogeneities on the resistance to O2 flow in health decreases with altitude.

Introduction

Current modelling of the O2 pathway (Wagner, 1993, 1996; Cano et al. 2013) is based on the concept that it is the functional integration amongst all individual components of the oxygen transport and utilization system (i.e. lungs and chest wall, heart, blood and circulation, and tissue mitochondria) which determines maximal overall O2 uptake ( . In these models, important simplifying assumptions were made. In particular, O2 exchange within the lungs was simplified by ignoring ventilation–perfusion (

. In these models, important simplifying assumptions were made. In particular, O2 exchange within the lungs was simplified by ignoring ventilation–perfusion ( inequality, and exchange focused only on alveolar–capillary diffusion. This was felt to be reasonable as the minimal

inequality, and exchange focused only on alveolar–capillary diffusion. This was felt to be reasonable as the minimal  inequality found in health (Wagner et al. 1974) is normally of minor importance to O2 exchange, while allowing for such inequality greatly increased model complexity. However, this would be an unacceptable simplification in cardiopulmonary diseases where

inequality found in health (Wagner et al. 1974) is normally of minor importance to O2 exchange, while allowing for such inequality greatly increased model complexity. However, this would be an unacceptable simplification in cardiopulmonary diseases where  inequality can be substantial. Similarly, within the muscles, potential heterogeneity of local metabolic capacity and demand (

inequality can be substantial. Similarly, within the muscles, potential heterogeneity of local metabolic capacity and demand ( ) in relation to blood flow distribution (

) in relation to blood flow distribution ( was not considered, and while diffusive movement of O2 from the muscle microcirculation to the mitochondria was modelled, the muscles were considered to be functionally homogeneous, i.e. with blood flow perfectly matched to O2 demand throughout. Much less information exists about normal

was not considered, and while diffusive movement of O2 from the muscle microcirculation to the mitochondria was modelled, the muscles were considered to be functionally homogeneous, i.e. with blood flow perfectly matched to O2 demand throughout. Much less information exists about normal  heterogeneity in muscle (Richardson et al. 2001), but using near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), preliminary data in normal subjects (Vogiatzis et al. 2015) suggest that

heterogeneity in muscle (Richardson et al. 2001), but using near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), preliminary data in normal subjects (Vogiatzis et al. 2015) suggest that  matching is much tighter than is

matching is much tighter than is  matching. Thus,

matching. Thus,  dispersion in muscle appears to be only about ¼ of

dispersion in muscle appears to be only about ¼ of  dispersion in normal lung (Wagner et al. 1987a,b1987b).

dispersion in normal lung (Wagner et al. 1987a,b1987b).

Another simplifying assumption was that all of the cardiac output flowed to the exercising muscles, which is clearly untrue. This is not of great quantitative importance to muscle O2 transport in health because of the ability to increase cardiac output to over 20 l min−1, rendering the fraction of cardiac output perfusing non-exercising tissue small. However, such an assumption would pose a substantial limitation if the models were applied to patients with chronic cardiorespiratory disease where peak exercise may elicit less than a doubling of the resting cardiac output and resting  .

.

The purpose of the study reported in the current paper was therefore to first expand the prior O2 transport pathway model (Wagner, 1993, 1996; Cano et al. 2013) by allowing for (a)  heterogeneity in the lung, (b)

heterogeneity in the lung, (b)  heterogeneity in the muscle, and (c) perfusion and metabolism in non-exercising tissues, and then to analyse the impact of possible heterogeneity in lungs and in peripheral exercising tissues, separately and combined, on overall O2 transport and utilization at maximum exercise, both in health and in disease. In health, we simulated exercise not just at sea level but at altitudes up to the summit of Mt Everest using as input data variables obtained in Operation Everest II (Sutton et al. 1988). In disease, we chose COPD as the example of pulmonary gas exchange heterogeneity because of availability of O2 transport data (Blanco et al. 2010), and because of general interest in muscle function in this disease.

heterogeneity in the muscle, and (c) perfusion and metabolism in non-exercising tissues, and then to analyse the impact of possible heterogeneity in lungs and in peripheral exercising tissues, separately and combined, on overall O2 transport and utilization at maximum exercise, both in health and in disease. In health, we simulated exercise not just at sea level but at altitudes up to the summit of Mt Everest using as input data variables obtained in Operation Everest II (Sutton et al. 1988). In disease, we chose COPD as the example of pulmonary gas exchange heterogeneity because of availability of O2 transport data (Blanco et al. 2010), and because of general interest in muscle function in this disease.

We then posed four questions: (a) in health, what are the potential effects of lung and muscle heterogeneity (each modelled over a wide range) on oxygen flux and partial pressures at all steps in the O2 pathway at sea level; (b) what is the impact of typical normal levels of heterogeneity on these variables when O2 availability is reduced by exposure to high altitude; (c) how substantial variations of the three least well established determinants of O2 flux and partial pressures in the transport–utilization pathway ( and P50 of the mitochondrial respiration curve and the extent of muscle heterogeneity) would affect both

and P50 of the mitochondrial respiration curve and the extent of muscle heterogeneity) would affect both  and mitochondrial

and mitochondrial  estimates; and (d) what is the effect of (measured) lung and possible muscle heterogeneity on overall oxygen uptake and mitochondrial

estimates; and (d) what is the effect of (measured) lung and possible muscle heterogeneity on overall oxygen uptake and mitochondrial  in mild and severe COPD, where O2 transport is less than normal.

in mild and severe COPD, where O2 transport is less than normal.

Methods

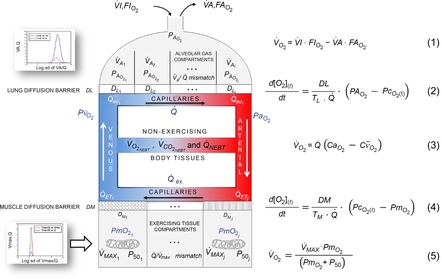

The prior O2 transport and utilization model

In the absence of heterogeneity in lungs or tissues, and ignoring metabolism and blood flow to non-exercising tissues, the system describing maximal O2 transport and utilization (Wagner, 1993, 1996; Cano et al. 2013) was composed of five mass conservation equations as shown in Fig.1, which is reproduced from Cano et al. (2013) for the convenience of the reader. These equations represent: (1) O2 transport by ventilation from the atmosphere to alveolar gas (eqn (1) in Fig.1); (2) O2 diffusion from the alveolar gas to the lung capillaries (eqn (2) in Fig.1); (3) O2 transport through the systemic circulation (eqn (3) in Fig.1); (4) O2 diffusion from systemic capillary blood to the muscle mitochondria (eqn (4) in Fig.1); and (5) mitochondrial O2 utilization (eqn (5) in Fig.1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the oxygen transport and utilization system.

The schematic representation is shown with the five associated mass conservation equations governing O2 transport (eqns (1)–(4)) and utilization (eqn (5)). Reproduced from Cano et al. (2013) with permission.

The inputs to these equations are, at maximal exercise: inspired O2 fraction ( ), ventilation (

), ventilation ( , inspired;

, inspired;  , expired), lung diffusing capacity (DL), cardiac output (

, expired), lung diffusing capacity (DL), cardiac output ( ), acid–base status, haemoglobin concentration ([Hb]), tissue (muscle) diffusing capacity (DM) and the characteristics of mitochondrial respiration (modelled as a hyperbolic curve with its two parameters,

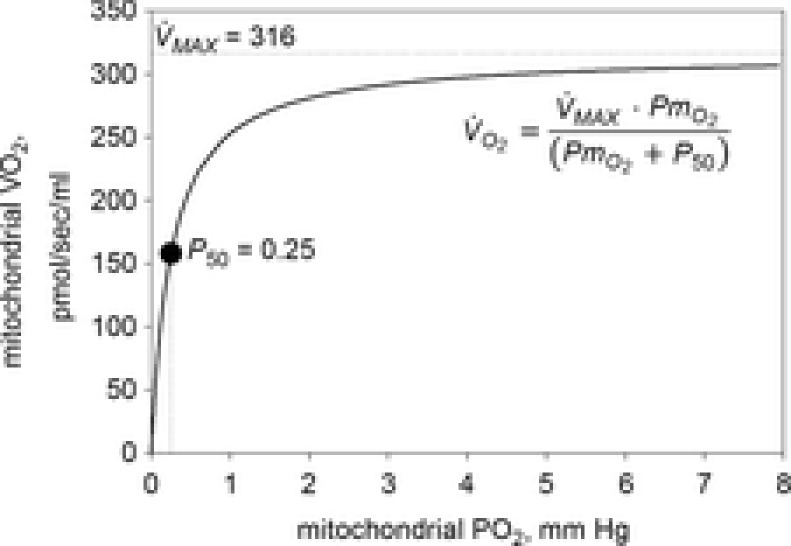

), acid–base status, haemoglobin concentration ([Hb]), tissue (muscle) diffusing capacity (DM) and the characteristics of mitochondrial respiration (modelled as a hyperbolic curve with its two parameters,  and P50, as defined below and illustrated in Fig.2). The five outputs, or unknowns, in these equations are the maximal rate of O2 uptake (

and P50, as defined below and illustrated in Fig.2). The five outputs, or unknowns, in these equations are the maximal rate of O2 uptake ( ) and alveolar, systemic arterial, venous and mitochondrial

) and alveolar, systemic arterial, venous and mitochondrial  values.

values.

Figure 2. Graphical depiction of the hyperbolic equation for oxidative phosphorylation.

The graphical depiction of the equation for oxidative phosphorylation (eqn (1) in Fig.1) is fitted to data of Scandurra & Gnaiger (2010; p. 16, Fig 3B).

While the focus is clearly on O2 transport, CO2 cannot be ignored in such a model because of the effects of CO2 retention, for example on the O2Hb dissociation curve and on alveolar  . Thus, the same processes and equations are used for CO2, (West, 1971), treating CO2 at every step side by side with O2 using the published CO2 dissociation curves and acid–base relationships based on Kelman's subroutines (Kelman, 1966) such that O2–CO2 interactions are accounted for both in the lungs and muscle. Furthermore, the effect of alveolar ventilation on arterial

. Thus, the same processes and equations are used for CO2, (West, 1971), treating CO2 at every step side by side with O2 using the published CO2 dissociation curves and acid–base relationships based on Kelman's subroutines (Kelman, 1966) such that O2–CO2 interactions are accounted for both in the lungs and muscle. Furthermore, the effect of alveolar ventilation on arterial  is also innately included as one of the input variables needed is total ventilation. An exception is made for mitochondrial respiration, where, because the mitochondrial respiration curve for O2 consumption does not apply to CO2, CO2 production is related to

is also innately included as one of the input variables needed is total ventilation. An exception is made for mitochondrial respiration, where, because the mitochondrial respiration curve for O2 consumption does not apply to CO2, CO2 production is related to  through a stipulated value of the respiratory quotient, and the solutions for both gases sought simultaneously.

through a stipulated value of the respiratory quotient, and the solutions for both gases sought simultaneously.

Modelling lung ventilation–perfusion inequality

To expand the model and allow for ventilation–perfusion ( inequality, ventilation and perfusion within the lung were distributed amongst a set of virtual lung compartments, each defined by its own ratio of ventilation (

inequality, ventilation and perfusion within the lung were distributed amongst a set of virtual lung compartments, each defined by its own ratio of ventilation ( to blood flow (

to blood flow ( , with the compartments conne-cted in parallel. This is exactly the same approach as first advanced by West in 1969 (West, 1969). Then, the computation for diffusive alveolar–capillary exchange, previously applied to just a single lung compartment representing the homogeneous lung, is now applied to all compartments in turn. The entering mixed venous blood is the same for all compartments, and the task is to compute the

, with the compartments conne-cted in parallel. This is exactly the same approach as first advanced by West in 1969 (West, 1969). Then, the computation for diffusive alveolar–capillary exchange, previously applied to just a single lung compartment representing the homogeneous lung, is now applied to all compartments in turn. The entering mixed venous blood is the same for all compartments, and the task is to compute the  and

and  values expected at the end of the capillary in each compartment of different

values expected at the end of the capillary in each compartment of different  ratio. This is done with a forward numerical integration procedure (Wagner et al. 1974), also used in Cano et al. (2013), and the outcome for each compartment depends on the compartmental

ratio. This is done with a forward numerical integration procedure (Wagner et al. 1974), also used in Cano et al. (2013), and the outcome for each compartment depends on the compartmental  and

and  ratios, the inspired gas and mixed venous blood O2 and CO2 composition, and the shape and position of the respective binding curves in blood. This approach is in fact the same as developed by Hammond & Hempleman (1987), and which is also contained within the multiple inert gas elimination technique (Wagner, 2008). Once all compartments have been subjected to this numerical integration, O2 and CO2 concentrations in their effluent blood are averaged in a perfusion-weighted manner to compute the O2 and CO2 profile of the systemic arterial blood that will reach both the exercising muscles and non-exercising tissues and organs.

ratios, the inspired gas and mixed venous blood O2 and CO2 composition, and the shape and position of the respective binding curves in blood. This approach is in fact the same as developed by Hammond & Hempleman (1987), and which is also contained within the multiple inert gas elimination technique (Wagner, 2008). Once all compartments have been subjected to this numerical integration, O2 and CO2 concentrations in their effluent blood are averaged in a perfusion-weighted manner to compute the O2 and CO2 profile of the systemic arterial blood that will reach both the exercising muscles and non-exercising tissues and organs.

In the present application, two means of data entry are possible for specifying the features of the  distribution, allowing flexibility. Individual compart-mental values for ventilation and blood flow can be used, or the compartments can be calculated based on a

distribution, allowing flexibility. Individual compart-mental values for ventilation and blood flow can be used, or the compartments can be calculated based on a  distribution containing one or more modes, using for each mode its first three moments (mean, dispersion and skewness) as originally programmed by West (1969). Both types of inputs end up providing a multi-compartmental

distribution containing one or more modes, using for each mode its first three moments (mean, dispersion and skewness) as originally programmed by West (1969). Both types of inputs end up providing a multi-compartmental  distribution (indicated in Fig.1). For simplicity, when computing the lung compartments based on a

distribution (indicated in Fig.1). For simplicity, when computing the lung compartments based on a  distribution, the lung diffusing capacity (DL) was always distributed in proportion to compartmental blood flow, so that compartmental

distribution, the lung diffusing capacity (DL) was always distributed in proportion to compartmental blood flow, so that compartmental  remains constant throughout the lung. This decision does not eliminate the opportunity to introduce actual data on

remains constant throughout the lung. This decision does not eliminate the opportunity to introduce actual data on  distribution when available.

distribution when available.

In summary, to allow for  heterogeneity, the single homogeneous lung ‘compartment’ in the prior model has been replaced by a multi-compartment model built from the algorithms of West (1969) as modified by Hammond & Hempleman (1987) and which allows for both

heterogeneity, the single homogeneous lung ‘compartment’ in the prior model has been replaced by a multi-compartment model built from the algorithms of West (1969) as modified by Hammond & Hempleman (1987) and which allows for both  inequality and diffusive exchange. Just as in the prior model, necessary inputs remain the composition of inspired gas and mixed venous blood, and the output remains the composition of systemic arterial blood destined for the muscles and other tissues.

inequality and diffusive exchange. Just as in the prior model, necessary inputs remain the composition of inspired gas and mixed venous blood, and the output remains the composition of systemic arterial blood destined for the muscles and other tissues.

Modelling peripheral heterogeneity

Similarly to lung ventilation–perfusion mismatch, tissue heterogeneities are considered as (regional) variability in a functional ratio. However, instead of  being that ratio as in the lung, it is the ratio of mitochondrial metabolic capacity (

being that ratio as in the lung, it is the ratio of mitochondrial metabolic capacity ( ) to blood flow (

) to blood flow ( ) that is considered in the muscles. Here,

) that is considered in the muscles. Here,  is the local mitochondrial maximal metabolic capacity to use O2, and is the very same parameter as

is the local mitochondrial maximal metabolic capacity to use O2, and is the very same parameter as  in eqn (5), Fig.1. The ratio

in eqn (5), Fig.1. The ratio  in essence expresses the balance between O2 supply (

in essence expresses the balance between O2 supply ( ) and O2 demand (

) and O2 demand ( ). In the prior model, the muscle was considered homogeneous in terms of

). In the prior model, the muscle was considered homogeneous in terms of  ratios, but now the muscle is considered as a parallel collection of muscle ‘units’ each with its own ratio of

ratios, but now the muscle is considered as a parallel collection of muscle ‘units’ each with its own ratio of  . Exactly as with the lung, the

. Exactly as with the lung, the  distribution can be specified either as a set of individual compartmental values for

distribution can be specified either as a set of individual compartmental values for  , DM,

, DM,  and P50, or computed from the moments of a (multimodal)

and P50, or computed from the moments of a (multimodal)  distribution. While it would be possible to assign every

distribution. While it would be possible to assign every  compartment a unique mitochondrial P50 (see eqn (5) in Fig.1), this has not been modelled to date, and P50 has been taken to be constant throughout any single muscle. Also as in the lung, diffusion is considered in every

compartment a unique mitochondrial P50 (see eqn (5) in Fig.1), this has not been modelled to date, and P50 has been taken to be constant throughout any single muscle. Also as in the lung, diffusion is considered in every  unit, with the diffusing capacity DM distributed in proportion to

unit, with the diffusing capacity DM distributed in proportion to  , just as for the lung. However, the algorithm can accommodate different values across compartments for both P50 and DM if desired. The same forward integration procedure is used as in the prior model (Cano et al. 2013), when it was applied to the entire muscle considered as one homogeneous unit to compute each muscle compartment's effluent venous O2 and CO2 levels for the given inflowing arterial blood composition, and the

, just as for the lung. However, the algorithm can accommodate different values across compartments for both P50 and DM if desired. The same forward integration procedure is used as in the prior model (Cano et al. 2013), when it was applied to the entire muscle considered as one homogeneous unit to compute each muscle compartment's effluent venous O2 and CO2 levels for the given inflowing arterial blood composition, and the  and

and  ratios of the unit. Again as in the lung, the effluent venous blood from all muscle units is combined, or mixed, in terms of both O2 and CO2 concentrations, and a resulting mixed muscle venous

ratios of the unit. Again as in the lung, the effluent venous blood from all muscle units is combined, or mixed, in terms of both O2 and CO2 concentrations, and a resulting mixed muscle venous  and

and  is then calculated. Finally, this blood is mixed with that from the non-exercising tissues (see below). This mixed venous blood returns to the lungs for re-oxygenation.

is then calculated. Finally, this blood is mixed with that from the non-exercising tissues (see below). This mixed venous blood returns to the lungs for re-oxygenation.

In summary, to allow for  heterogeneity, the single homogeneous muscle ‘compartment’ in the prior model has been replaced by a multi-compartment model which allows for both

heterogeneity, the single homogeneous muscle ‘compartment’ in the prior model has been replaced by a multi-compartment model which allows for both  inequality and diffusion impairment. Similarly to the prior model, necessary additional inputs remain the composition of arterial blood, and the blood binding characteristics of O2 and CO2. The output remains the composition of mixed muscle venous blood destined for return to the lungs for re-oxygenation.

inequality and diffusion impairment. Similarly to the prior model, necessary additional inputs remain the composition of arterial blood, and the blood binding characteristics of O2 and CO2. The output remains the composition of mixed muscle venous blood destined for return to the lungs for re-oxygenation.

In this section, the expression of peripheral heterogeneity using the oxygen flow ( instead of blood flow (

instead of blood flow ( was considered, but since at any given arterial

was considered, but since at any given arterial  , the arterial blood entering any muscle region has the same oxygenation, the distribution of

, the arterial blood entering any muscle region has the same oxygenation, the distribution of  will not differ in dispersion from that of

will not differ in dispersion from that of  delivery. Moreover, O2 concentration is an outcome variable. Hence, we cannot in practice adopt O2 delivery as the denominator.

delivery. Moreover, O2 concentration is an outcome variable. Hence, we cannot in practice adopt O2 delivery as the denominator.

Modelling metabolism and blood flow to non-exercising tissues

Non-exercising tissue blood flow and metabolism are incorporated simply by assigning values for total non-exercising tissue  and

and  , and using the Fick principle to compute the tissue venous O2 concentration. Then, a mixing equation combines venous blood from this non-exercising tissue with that from the mixed muscle venous blood (see above) in proportion to the blood flow rates assigned to the non-exercising tissues and muscles respectively, to form what will be pulmonary arterial blood reaching the lungs for re-oxygenation.

, and using the Fick principle to compute the tissue venous O2 concentration. Then, a mixing equation combines venous blood from this non-exercising tissue with that from the mixed muscle venous blood (see above) in proportion to the blood flow rates assigned to the non-exercising tissues and muscles respectively, to form what will be pulmonary arterial blood reaching the lungs for re-oxygenation.

Achieving a solution for the model

In the prior model it was explained (Cano et al. 2013) how the model was run and a solution achieved. The same process is used with the above-described expansions in the current paper. In brief, a starting estimate is made for the composition of mixed venous blood entering the lungs, and for that estimate, the lung component is executed over the many  compartments and the end-capillary O2 and CO2 concentrations averaged over all compartments (weighted by compartmental blood flow) to yield an estimate of systemic arterial

compartments and the end-capillary O2 and CO2 concentrations averaged over all compartments (weighted by compartmental blood flow) to yield an estimate of systemic arterial  and

and  . These are then used as input data for the muscle part of the system, and that component is run once for each

. These are then used as input data for the muscle part of the system, and that component is run once for each  compartment. The effluent compartmental venous O2 and CO2 levels are then averaged (again blood flow-weighted), and mixed with the blood draining the non-exercising tissues (see previous section). It is the

compartment. The effluent compartmental venous O2 and CO2 levels are then averaged (again blood flow-weighted), and mixed with the blood draining the non-exercising tissues (see previous section). It is the  and

and  of this mixed blood that is the new estimate at mixed venous

of this mixed blood that is the new estimate at mixed venous  and

and  for the next iteration (or cycle) of pulmonary gas exchange: To this point, all that has changed between the first and second cycles is the composition of mixed venous blood. After pulmonary gas exchange calculations using this new venous blood composition are complete, new values of arterial blood

for the next iteration (or cycle) of pulmonary gas exchange: To this point, all that has changed between the first and second cycles is the composition of mixed venous blood. After pulmonary gas exchange calculations using this new venous blood composition are complete, new values of arterial blood  and

and  are calculated, and now muscle O2 exchange is recomputed, from which new values of mixed venous

are calculated, and now muscle O2 exchange is recomputed, from which new values of mixed venous  and

and  are calculated. This cycling back and forth between the lungs and the tissues is continued until the five

are calculated. This cycling back and forth between the lungs and the tissues is continued until the five  estimates – one computed from each of the five equations in Fig.1 – are identical (to within ± 0.1 ml min−1). At this point, stability of all

estimates – one computed from each of the five equations in Fig.1 – are identical (to within ± 0.1 ml min−1). At this point, stability of all  values (alveolar, arterial, muscle venous and mitochondrial) in the face of further cycling between the lungs and tissues is also achieved. When this is observed, the governing requirement for conservation of mass has been achieved, and this signals the end of the run.

values (alveolar, arterial, muscle venous and mitochondrial) in the face of further cycling between the lungs and tissues is also achieved. When this is observed, the governing requirement for conservation of mass has been achieved, and this signals the end of the run.

Analysis and input data for simulations

As mentioned above, four questions were posed, and these are discussed below.

First, in health, we assessed the effects of a wide range of lung and tissue functional heterogeneities on oxygen tensions and utilization at all steps of the O2 pathway. This extensive exploration was carried out for conditions of maximal exercise breathing room air at sea level. To this end, input data defining O2 transport conductances (i.e. ventilation, cardiac output, lung and muscle diffusional conductances) from normal subjects exercising maximally at sea level in Operation Everest II (Sutton et al. 1988) were used just as for the previous models (Wagner, 1993, 1996). Lung heterogeneity was analysed from complete homogeneity ( , second moment of the blood flow (

, second moment of the blood flow ( distribution on a logarithmic

distribution on a logarithmic  scale equals zero), to very high inhomogeneity (

scale equals zero), to very high inhomogeneity ( ) as might be seen in the critically ill. We also explored the effects of skeletal muscle heterogeneity on overall O2 uptake (

) as might be seen in the critically ill. We also explored the effects of skeletal muscle heterogeneity on overall O2 uptake ( using a similar wide range of

using a similar wide range of  (second moment of the muscle metabolism (

(second moment of the muscle metabolism ( distribution on a logarithmic

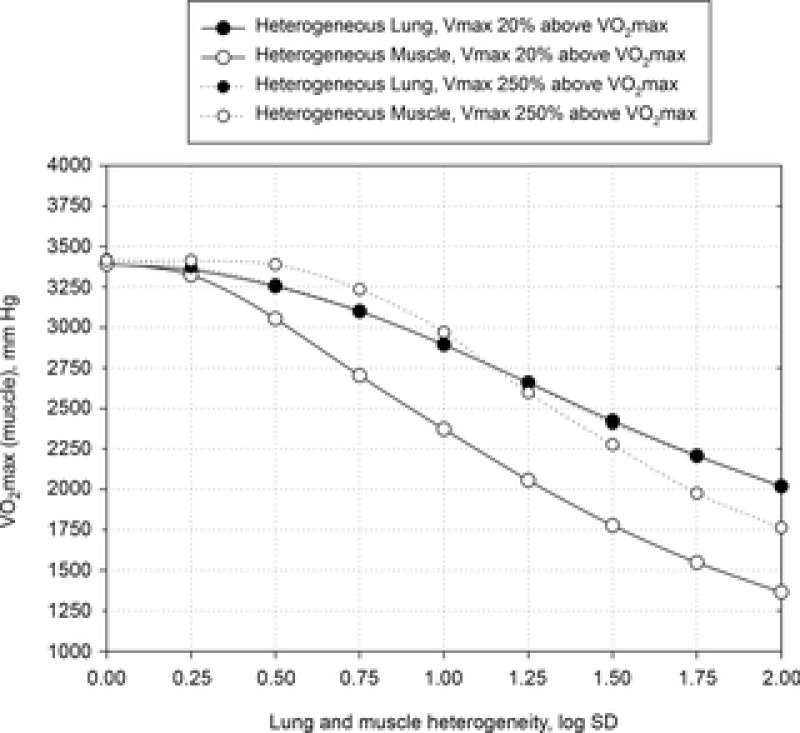

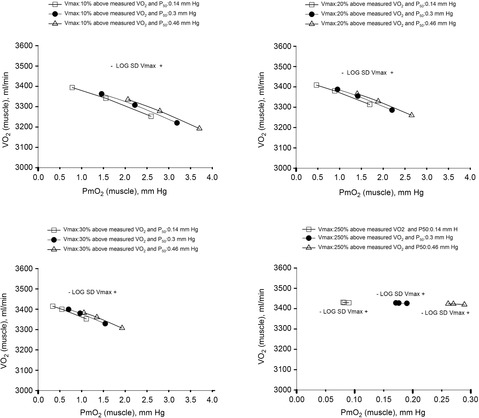

distribution on a logarithmic  scale equals zero) from 0 to 2. The effects of lung and skeletal muscle heterogeneity on oxygen transport and utilization are displayed in Figs3 and 4. In Fig.3, and the first section in Results, the impact of skeletal muscle heterogeneity on

scale equals zero) from 0 to 2. The effects of lung and skeletal muscle heterogeneity on oxygen transport and utilization are displayed in Figs3 and 4. In Fig.3, and the first section in Results, the impact of skeletal muscle heterogeneity on  is assessed at two different levels of

is assessed at two different levels of  corresponding to 120% and 250%

corresponding to 120% and 250%  .

.

Figure 3. Effects of potential lung and muscle heterogeneities on maximal O2 transport and utilization.

Independent effects of lung  heterogeneity (filled circles) and muscle

heterogeneity (filled circles) and muscle  heterogeneity (open circles) on maximal muscle oxygen uptake (

heterogeneity (open circles) on maximal muscle oxygen uptake ( ), using input data defining O2 transport conductances from normal subjects exercising maximally at sea level in Operation Everest II (Sutton et al. 1988). Results shown for

), using input data defining O2 transport conductances from normal subjects exercising maximally at sea level in Operation Everest II (Sutton et al. 1988). Results shown for  20% higher than measured

20% higher than measured (continuous line) and

(continuous line) and  2.5-fold higher than measured

2.5-fold higher than measured  (dotted line). Healthy subjects show pulmonary

(dotted line). Healthy subjects show pulmonary  between 0.3 and 0.6 (Wagner et al. 1974), whereas skeletal muscle heterogeneity (

between 0.3 and 0.6 (Wagner et al. 1974), whereas skeletal muscle heterogeneity ( ) presents an average value of 0.10 (Vogiatzis et al. 2015). In patients with moderate to severe COPD,

) presents an average value of 0.10 (Vogiatzis et al. 2015). In patients with moderate to severe COPD,  can present values close to 1.0, but no published data on

can present values close to 1.0, but no published data on  are available. Finally, critically ill patients admitted in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) may show lung heterogeneity values close to 2.0. Again, no information on

are available. Finally, critically ill patients admitted in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) may show lung heterogeneity values close to 2.0. Again, no information on  is available.

is available.

Figure 4. Combined and separate effects of lung and muscle heterogeneities on the O2 transport and utilization system.

Combined and separated effects of varying degrees of lung ventilation–perfusion heterogeneity (SDQ) and varying degrees of exercising muscle mitochondrial metabolic capacity–blood flow heterogeneities ( ) on the O2 transport pathway:

) on the O2 transport pathway:  on arterial blood (upper left panel), venous blood (upper right panel) and mitochondria (two central panels), maximal muscle oxygen uptake (lower left panel), and, maximum degree of oxygen unbalance between mitochondrial (

on arterial blood (upper left panel), venous blood (upper right panel) and mitochondria (two central panels), maximal muscle oxygen uptake (lower left panel), and, maximum degree of oxygen unbalance between mitochondrial ( ) of muscle compartments and mean effluent venous (

) of muscle compartments and mean effluent venous ( ) oxygen levels (lower-right panel). See text for details.

) oxygen levels (lower-right panel). See text for details.

The rationale behind a value for  of 4.6 l min−1, which is 20% higher than the measured

of 4.6 l min−1, which is 20% higher than the measured  (3.8 l min−1) at sea level in Operation Everest II (Sutton et al. 1988), is that it is a conservative estimate. This is so, because it is known that measured

(3.8 l min−1) at sea level in Operation Everest II (Sutton et al. 1988), is that it is a conservative estimate. This is so, because it is known that measured  is less than mitochondrial capacity to use O2 (i.e.

is less than mitochondrial capacity to use O2 (i.e.  in healthy fit subjects and exercise capacity is known to be increased within this range when breathing 100% O2 (Welch, 1982; Knight et al. 1992).

in healthy fit subjects and exercise capacity is known to be increased within this range when breathing 100% O2 (Welch, 1982; Knight et al. 1992).

However, we acknowledge that reports on subjects exercising a limited amount of muscle mass, (i.e. knee extensor of one limb); Andersen & Saltin, 1985) indicate the potential for markedly higher  values up to 250% of

values up to 250% of  (which would scale to 9.5 l min−1 for

(which would scale to 9.5 l min−1 for  measured in subjects from Operation Everest II). In the study by Andersen & Saltin, a rate of 350 ml kg−1 was measured, which extrapolated to a conservative estimate of 27 kg of exercising muscle mass corresponds to a

measured in subjects from Operation Everest II). In the study by Andersen & Saltin, a rate of 350 ml kg−1 was measured, which extrapolated to a conservative estimate of 27 kg of exercising muscle mass corresponds to a  value of 9.5 l min−1. Consequently, these two

value of 9.5 l min−1. Consequently, these two  values (4.6 and 9.5 l min−1) were used for the simulations displayed in Fig.3.

values (4.6 and 9.5 l min−1) were used for the simulations displayed in Fig.3.

For the mitochondrialP50, we used a value of 0.3 mmHg, similar to what has been found experimentally in vitro (Wilson et al. 1977; Gnaiger et al. 1998; Scandurra & Gnaiger, 2010).

For non-exercising body tissues we used typical resting total values of  (300 ml min−1),

(300 ml min−1),  (240 ml min−1) and blood flow (20% of total blood flow at peak exercise).

(240 ml min−1) and blood flow (20% of total blood flow at peak exercise).

The second question examined the effects of heterogeneity in healthy lungs and muscle on O2 transport and utilization at altitude. For the lung we used  as a value commonly seen during exercise (Wagner et al. 1987a,b1987b). This value is near the upper end of the normal range, which is 0.3–0.6 (Wagner et al. 1987a,b1987b). In muscle, we used preliminary unpublished estimates of

as a value commonly seen during exercise (Wagner et al. 1987a,b1987b). This value is near the upper end of the normal range, which is 0.3–0.6 (Wagner et al. 1987a,b1987b). In muscle, we used preliminary unpublished estimates of  . Again for P50, we used a value of 0.3 mmHg and for

. Again for P50, we used a value of 0.3 mmHg and for  we used a conservative value 20% higher than the measured

we used a conservative value 20% higher than the measured . The input data defining the O2 transport conductances again came from normal subjects exercising maximally at sea level and altitude in Operation Everest II (Sutton et al. 1988) as used above and again typical resting total values of

. The input data defining the O2 transport conductances again came from normal subjects exercising maximally at sea level and altitude in Operation Everest II (Sutton et al. 1988) as used above and again typical resting total values of  (300 ml min−1),

(300 ml min−1),  (240 ml min−1) and blood flow (20% of total blood flow at peak exercise) were considered for non-exercising body tissues. However, to study the consequences at more altitudes than were examined in Operation Everest II (which were sea level, 4600 m, 6100 m, 7600 m and 8848 m), O2 transport conductance parameters were linearly interpolated (Table1) at 305 m (1000 ft) elevation increments from the data obtained at each of the five altitudes studied in Operation Everest II (Sutton et al. 1988).

(240 ml min−1) and blood flow (20% of total blood flow at peak exercise) were considered for non-exercising body tissues. However, to study the consequences at more altitudes than were examined in Operation Everest II (which were sea level, 4600 m, 6100 m, 7600 m and 8848 m), O2 transport conductance parameters were linearly interpolated (Table1) at 305 m (1000 ft) elevation increments from the data obtained at each of the five altitudes studied in Operation Everest II (Sutton et al. 1988).

Table 1.

Input parameters for the modelling of the oxygen transport system in health at sea level and altitude

| Altitude (ft) | Barometric pressure (PB; mmHg) | Body temperature (T; °C) | Haemoglobin concentration ([Hb]; g dl–1) | Alveolar ventilation ( (BTPS); l min–1) (BTPS); l min–1) |

Blood flow ( ; l min–1) ; l min–1) |

Total lung O2 diffusing capacity (DL; ml min–1 mmHg–1) | Total muscle O2 diffusing capacity (DM; ml min–1 mmHg–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 760 | 38 | 14.2 | 128.3 | 25.0 | 50.9 | 104.6 |

| 5000 | 639 | 38 | 14.9 | 137.1 | 23.5 | 60.9 | 97.1 |

| 10,000 | 534 | 38 | 15.5 | 145.9 | 22.0 | 70.9 | 89.6 |

| 15,000 | 442 | 38 | 16.2 | 154.6 | 20.5 | 80.9 | 82.1 |

| 16,000 | 426 | 37.9 | 16.3 | 156.4 | 20.2 | 82.9 | 80.6 |

| 17,000 | 410 | 37.8 | 16.5 | 158.1 | 19.9 | 84.9 | 79.1 |

| 18,000 | 394 | 37.7 | 16.6 | 159.9 | 19.6 | 86.9 | 77.6 |

| 19,000 | 380 | 37.6 | 16.7 | 161.6 | 19.3 | 88.9 | 76.1 |

| 20,000 | 365 | 37.5 | 16.9 | 163.4 | 19.0 | 90.9 | 74.6 |

| 21,000 | 351 | 37.4 | 17.0 | 165.2 | 18.7 | 92.9 | 73.1 |

| 22,000 | 337 | 37.3 | 17.1 | 166.9 | 18.4 | 94.9 | 71.6 |

| 23,000 | 324 | 37.2 | 17.2 | 168.7 | 18.1 | 96.9 | 70.1 |

| 24,000 | 311 | 37.1 | 17.4 | 170.4 | 17.8 | 98.9 | 68.6 |

| 25,000 | 299 | 37 | 17.5 | 172.2 | 17.5 | 100.9 | 67.1 |

| 26,000 | 286 | 37 | 17.6 | 173.9 | 17.2 | 102.9 | 65.6 |

| 27,000 | 275 | 37 | 17.8 | 175.7 | 16.9 | 104.9 | 64.1 |

| 28,000 | 264 | 37 | 17.9 | 177.4 | 16.6 | 106.9 | 62.6 |

| 29,000 | 253 | 37 | 18.0 | 179.2 | 16.3 | 108.9 | 61.1 |

| 30,000 | 243 | 37 | 18.2 | 181.0 | 16.0 | 110.9 | 59.6 |

For the third and forth questions we assessed how substantial variations of the three least well established determinants of O2 flux and partial pressures in the transport–utilization pathway ( and P50 of the mitochondrial respiration curve and

and P50 of the mitochondrial respiration curve and ) would affect both

) would affect both  and mitochondrial

and mitochondrial  estimates, in health (third question) and in COPD (fourth question). Input data defining O2 transport conductances and lung heterogeneity (i.e.

estimates, in health (third question) and in COPD (fourth question). Input data defining O2 transport conductances and lung heterogeneity (i.e. ) from normal subjects exercising maximally at sea level in Operation Everest II (Sutton et al. 1988) were used in health. In disease, measured O2 conductances and lung heterogeneity data came from two previously studied COPD patients (Blanco et al. 2010) exercising maximally (Table2), one with mild (FEV1 = 66% predicted post-bronchodilator) and one with severe (FEV1 = 23% predicted post-bronchodilator) COPD. However, even if reasonable, the values of

) from normal subjects exercising maximally at sea level in Operation Everest II (Sutton et al. 1988) were used in health. In disease, measured O2 conductances and lung heterogeneity data came from two previously studied COPD patients (Blanco et al. 2010) exercising maximally (Table2), one with mild (FEV1 = 66% predicted post-bronchodilator) and one with severe (FEV1 = 23% predicted post-bronchodilator) COPD. However, even if reasonable, the values of  and P50 assumed to answer the previous question are uncertain, let alone whether there is significant

and P50 assumed to answer the previous question are uncertain, let alone whether there is significant  heterogeneity. Because of this, we carried out simulations over a wide range of possible values of these variables, as indicated in Fig.6. In the case of

heterogeneity. Because of this, we carried out simulations over a wide range of possible values of these variables, as indicated in Fig.6. In the case of  , we used a values of 4.2, 4.6 and 4.9 l min−1 (10, 20% and 30% higher than actual

, we used a values of 4.2, 4.6 and 4.9 l min−1 (10, 20% and 30% higher than actual  , respectively). Moreover, a

, respectively). Moreover, a  value of 9.5 l min−1 (250%

value of 9.5 l min−1 (250%  ) was also considered in health because of the rationale described above.

) was also considered in health because of the rationale described above.

Table 2.

Input parameters for the modelling of the oxygen transport system in disease (moderate and severe COPD)

| Moderately limited | Severely limited | |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | transport | transport |

| Forced expired volume in the 1st second (FEV1; % predicted post-bronchodilator) | 66 | 23 |

| Forced vital capacity (FVC; % predicted post-bronchodilator) | 84 | 33 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.58 | 0.54 |

Log SD

|

0.67 | 0.86 |

| Barometric pressure (PB; mmHg) | 758 | 765 |

Fractional inspired oxygen ( ) ) |

0.2093 | 0.2093 |

| Haemoglobin concentration ([Hb]; g dl–1) | 14.4 | 12.5 |

| O2 dissociation curve (P50; mmHg) | 26.8 | 26.8 |

| Body temperature (T; °C) | 37.0 | 36.8 |

| Weight (kg) | 60 | 36 |

| Body mass index (BMI; kg m–2) | 19.8 | 15.2 |

Resting ventilation ( (BTPS); l min–1) (BTPS); l min–1) |

7.11 | 7.44 |

Resting cardiac output ( ; l min–1) ; l min–1) |

3.68 | 3.20 |

Resting  (ml min–1) (ml min–1) |

235 | 159 |

Resting  (ml min–1) (ml min–1) |

174 | 103 |

Resting arterial  ( ( ; mmHg) ; mmHg) |

80 | 59 |

Resting arterial  ( ( ; mmHg) ; mmHg) |

35 | 46 |

| Resting lactate (mmol l–1) | 1.47 | 0.81 |

Exercise ventilation ( (BTPS); l min–1) (BTPS); l min–1) |

35.3 | 8.2 |

Exercise cardiac output ( ; l min–1) ; l min–1) |

7.87 | 3.98 |

Exercise ( ; ml·min–1) ; ml·min–1) |

914 | 355 |

Exercise arterial  ( ( ; mmHg) ; mmHg) |

90 | 59 |

Exercise arterial  ( ( ; mmHg) ; mmHg) |

31 | 49 |

| Exercise lung O2 diffusing capacity (DL; ml min–1 mmHg–1) | 100 | 11 |

| Exercise muscle O2 diffusing capacity (DM; ml min–1·mmHg–1) | 26 | 9 |

| Exercise lactate (mmol l–1) | 3.55 | 2.03 |

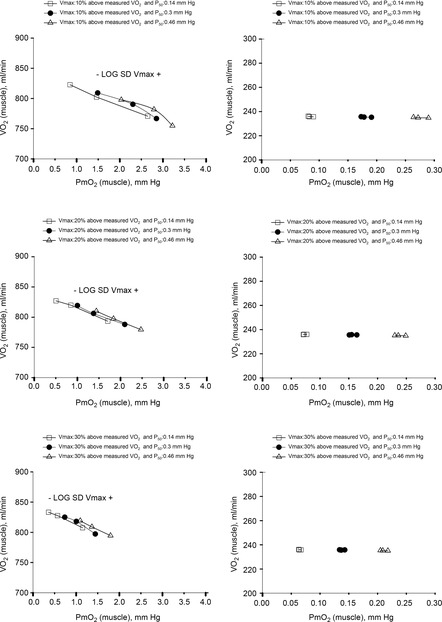

Figure 6. Sensitivity analysis of mitochondrial respiration and muscle heterogeneity estimates in health.

Effects of muscle bioenergetics (mitochondrial respiration  and P50 parameters) and muscle peripheral heterogeneities on muscle

and P50 parameters) and muscle peripheral heterogeneities on muscle  and mitochondrial

and mitochondrial  (

( ) in health at sea level.

) in health at sea level.  is taken as 10% (upper left panel), 20% (upper right panel), 30% (lower left panel) and 250% (lower right panel) greater than measured

is taken as 10% (upper left panel), 20% (upper right panel), 30% (lower left panel) and 250% (lower right panel) greater than measured  . For each

. For each  , three mitochondrial P50 values (0.14, 0.3 and 0.46 mmHg) and three degrees (0.1, 0.2 and 0.3) of muscle perfusion–metabolism inhomogeneity (

, three mitochondrial P50 values (0.14, 0.3 and 0.46 mmHg) and three degrees (0.1, 0.2 and 0.3) of muscle perfusion–metabolism inhomogeneity ( ) were evaluated. See text for details.

) were evaluated. See text for details.

For mitochondrial P50, we used values lower (0.14 mmHg) and higher (0.46 mmHg) than 0.3 mmHg, the value found experimentally in vitro (Wilson et al. 1977; Gnaiger et al. 1998; Scandurra & Gnaiger, 2010). Finally, to assess how sensitive the outcomes are to the degree of heterogeneity, we also carried out calculations with  values of 0.1 (healthy subject estimates), 0.2 and 0.3. With respect to non-exercising body tissues, we used typical resting total values of

values of 0.1 (healthy subject estimates), 0.2 and 0.3. With respect to non-exercising body tissues, we used typical resting total values of  (300 ml min−1),

(300 ml min−1),  (240 ml min−1) and blood flow (20% of total blood flow at peak exercise) for normal subjects.

(240 ml min−1) and blood flow (20% of total blood flow at peak exercise) for normal subjects.

For the two previously studied COPD patients (Blanco et al. 2010) exercising maximally we used measured resting values of whole body  (

( and

and  (Table2), along with a blood flow estimate (

(Table2), along with a blood flow estimate ( ) from the following formula, which expresses the concept that blood flow is proportional to metabolic rate:

) from the following formula, which expresses the concept that blood flow is proportional to metabolic rate:  .

.

Results

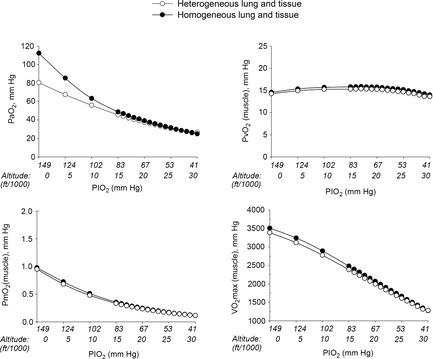

Effects of potential lung and muscle heterogeneities on O2 transport and utilization in healthy subjects exercising maximally at sea level

Figure 3 shows the independent effects of lung  heterogeneity (filled circles) and muscle

heterogeneity (filled circles) and muscle  heterogeneity (open circles) on maximal muscle oxygen uptake (

heterogeneity (open circles) on maximal muscle oxygen uptake ( ), in normal subjects exercising maximally at sea level. In this figure, both

), in normal subjects exercising maximally at sea level. In this figure, both  and

and  heterogeneity has been varied over a wide range of log SD, from 0 to 2.0. Healthy subjects show pulmonary

heterogeneity has been varied over a wide range of log SD, from 0 to 2.0. Healthy subjects show pulmonary  between 0.30 and 0.60 (Wagner et al. 1987a), whereas skeletal muscle heterogeneity (

between 0.30 and 0.60 (Wagner et al. 1987a), whereas skeletal muscle heterogeneity ( ) presents an average value of 0.10 (Vogiatzis et al. 2015). In patients with moderate to severe COPD,

) presents an average value of 0.10 (Vogiatzis et al. 2015). In patients with moderate to severe COPD,  can present values close to 1.0, but no published data on

can present values close to 1.0, but no published data on  are available. Finally, critically ill patients admitted in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) may show lung heterogeneity values close to 2.0, but no information on

are available. Finally, critically ill patients admitted in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) may show lung heterogeneity values close to 2.0, but no information on  is available. The main result from Fig.3 is that heterogeneity in muscle affects O2 availability more than does heterogeneity in the lungs if

is available. The main result from Fig.3 is that heterogeneity in muscle affects O2 availability more than does heterogeneity in the lungs if  is only 20% higher than

is only 20% higher than  . However, using the higher

. However, using the higher  (i.e. 9.5 l min−1), the effects of lung and muscle heterogeneity are similar. On the other hand, the impact of lung heterogeneity on

(i.e. 9.5 l min−1), the effects of lung and muscle heterogeneity are similar. On the other hand, the impact of lung heterogeneity on  is insensitive to the

is insensitive to the  values used. In addition, because muscle heterogeneity appears to be much less than that in the lung, both in health and COPD, based on a combination of published and unpublished data as mentioned, actual muscle heterogeneity has less of an impact on O2 transport than observed lung heterogeneity.

values used. In addition, because muscle heterogeneity appears to be much less than that in the lung, both in health and COPD, based on a combination of published and unpublished data as mentioned, actual muscle heterogeneity has less of an impact on O2 transport than observed lung heterogeneity.

The six panels in Fig.4 display the estimated (combined and separate) effects of lung and muscle heterogeneities on the O2 transport and utilization system. The upper-left panel indicates arterial  (

( over a range of exercising muscle

over a range of exercising muscle  mismatching (0 to 0.5), expressed as

mismatching (0 to 0.5), expressed as  . For each

. For each  value, the panel displays

value, the panel displays  values for different levels of lung

values for different levels of lung  heterogeneity, from the homogeneous lung

heterogeneity, from the homogeneous lung  to a highly heterogeneous lung (

to a highly heterogeneous lung ( . Each line represents the outcome at a given level of lung heterogeneity over a range of muscle heterogeneity. This panel shows that muscle heterogeneity has only a small effect on

. Each line represents the outcome at a given level of lung heterogeneity over a range of muscle heterogeneity. This panel shows that muscle heterogeneity has only a small effect on  at all levels of lung functional heterogeneities. However, as is well known,

at all levels of lung functional heterogeneities. However, as is well known,  inequality has a major impact on arterial oxygenation as shown. Likewise, the upper-right panel shows the effects of muscle heterogeneity on effluent muscle venous

inequality has a major impact on arterial oxygenation as shown. Likewise, the upper-right panel shows the effects of muscle heterogeneity on effluent muscle venous  (

( . The impact is moderate, and is greater than the effect on

. The impact is moderate, and is greater than the effect on  . However, it is quantitatively important only at high levels of tissue heterogeneity, especially in combination with lungs containing little heterogeneity.

. However, it is quantitatively important only at high levels of tissue heterogeneity, especially in combination with lungs containing little heterogeneity.

The two middle panels of Fig.4 show the relationships between mitochondrial  (

( among muscle regions (compartments) and skeletal muscle

among muscle regions (compartments) and skeletal muscle  functional heterogeneity. The left hand panel shows the lowest compartmental values of

functional heterogeneity. The left hand panel shows the lowest compartmental values of  (i.e. when

(i.e. when  is high) and the right hand panel shows the highest compartmental values of

is high) and the right hand panel shows the highest compartmental values of  (i.e. when

(i.e. when  is low). Note that the ordinate scales are very different in these two panels. These panels show that heterogeneity of

is low). Note that the ordinate scales are very different in these two panels. These panels show that heterogeneity of  ratios markedly expands the range of

ratios markedly expands the range of  levels among exercising skeletal muscle compartments. As in the top panels, each line in the two middle panels correspond to different levels of lung heterogeneity from a homogeneous lung (

levels among exercising skeletal muscle compartments. As in the top panels, each line in the two middle panels correspond to different levels of lung heterogeneity from a homogeneous lung ( to a highly heterogeneous lung (

to a highly heterogeneous lung ( .

.

The left middle panel shows that, as expected, the greater the peripheral heterogeneity, the lower the minimum  values. Moreover, we observe a moderate impact of lung heterogeneity on minimum

values. Moreover, we observe a moderate impact of lung heterogeneity on minimum  , but such impact decreases as skeletal muscle heterogeneity increases. Likewise, the right middle panel shows that skeletal muscle compartments with lowest

, but such impact decreases as skeletal muscle heterogeneity increases. Likewise, the right middle panel shows that skeletal muscle compartments with lowest  ratios may generate exceedingly high

ratios may generate exceedingly high  estimates that increase with tissue heterogeneity. Homogeneous lungs show the highest

estimates that increase with tissue heterogeneity. Homogeneous lungs show the highest  values for a given level of peripheral tissue functional heterogeneity.

values for a given level of peripheral tissue functional heterogeneity.

The lower left panel indicates that muscle heterogeneities have small effects on total muscle  , especially compared with lung heterogeneities that show a significant impact on muscle

, especially compared with lung heterogeneities that show a significant impact on muscle  . Finally, the lower right panel displays the maximum estimates for

. Finally, the lower right panel displays the maximum estimates for  among muscle regions (as seen in the middle right panel of the same figure) plotted against the corresponding mean effluent muscle

among muscle regions (as seen in the middle right panel of the same figure) plotted against the corresponding mean effluent muscle  (from the top right panel). The individual lines indicate different levels of muscle heterogeneities, from a homogeneous tissue (

(from the top right panel). The individual lines indicate different levels of muscle heterogeneities, from a homogeneous tissue ( at the bottom to heterogeneous muscle (

at the bottom to heterogeneous muscle ( at the top. In the panel, the dashed straight line corresponds to the identity line. The point of presenting this relationship is to show that when the dispersion of muscle

at the top. In the panel, the dashed straight line corresponds to the identity line. The point of presenting this relationship is to show that when the dispersion of muscle  is 0.2 or greater, some regions of muscle will have mitochondrial

is 0.2 or greater, some regions of muscle will have mitochondrial  values that exceed

values that exceed  of the effluent muscle venous blood.

of the effluent muscle venous blood.

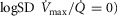

The role of functional heterogeneities, lung and muscle, on O2 transport and utilization in healthy subjects at altitude

The four panels in Fig.5 display the effects of altitude on four key outcome variables at maximal exercise – arterial, muscle venous, and mitochondrial  and

and  itself. Two relationships are shown in each panel – that computed in the absence of either lung or muscle heterogeneity, and that computed allowing for reasonable normal estimates of heterogeneity in each location as listed above in the Methods section (

itself. Two relationships are shown in each panel – that computed in the absence of either lung or muscle heterogeneity, and that computed allowing for reasonable normal estimates of heterogeneity in each location as listed above in the Methods section ( heterogeneity in the lung quantified by a dispersion value (

heterogeneity in the lung quantified by a dispersion value ( of 0.5,

of 0.5,  heterogeneity in muscle quantified using an estimate of dispersion (

heterogeneity in muscle quantified using an estimate of dispersion ( ) of 0.1, non-exercising body tissues using typical resting total values of

) of 0.1, non-exercising body tissues using typical resting total values of  (300 ml min−1),

(300 ml min−1),  (240 ml min−1) and 20% of total blood flow at peak exercise, and a conservative

(240 ml min−1) and 20% of total blood flow at peak exercise, and a conservative  value 20% higher than the measured

value 20% higher than the measured  ). Except for arterial

). Except for arterial  at sea level and altitudes up to about 10,000 ft, the effects of typical levels of heterogeneity are seen to be small, and diminish progressively with increasing altitude.

at sea level and altitudes up to about 10,000 ft, the effects of typical levels of heterogeneity are seen to be small, and diminish progressively with increasing altitude.

Figure 5. Role of functional heterogeneities, lung and muscle, on the O2 transport and utilization system in healthy subjects at altitude.

Effects of functional inhomogeneity on arterial  (upper left panel), venous

(upper left panel), venous  (upper right panel), mitochondrial

(upper right panel), mitochondrial  (lower left panel) and

(lower left panel) and  (lower right panel) at sea level and altitude. Functional inhomogeneity is expressed as the combined effects of lung ventilation–perfusion inequalities and skeletal muscle perfusion–metabolism mismatching. Mitochondrial respiration parameters were fixed to a conservative

(lower right panel) at sea level and altitude. Functional inhomogeneity is expressed as the combined effects of lung ventilation–perfusion inequalities and skeletal muscle perfusion–metabolism mismatching. Mitochondrial respiration parameters were fixed to a conservative  of 4584 ml min−1 and a P50 of 0.3 mmHg. Filled circles correspond to simulations outputs when considering both homogeneous lung and tissues. Open circles represent simulation outputs when using reasonable estimates for lung ventilation–perfusion (

of 4584 ml min−1 and a P50 of 0.3 mmHg. Filled circles correspond to simulations outputs when considering both homogeneous lung and tissues. Open circles represent simulation outputs when using reasonable estimates for lung ventilation–perfusion ( of 0.5), tissue perfusion–metabolism (

of 0.5), tissue perfusion–metabolism ( of 0.1), and the metabolic rate of non-exercising tissues (with an assigned

of 0.1), and the metabolic rate of non-exercising tissues (with an assigned  of 300 ml min−1 and a

of 300 ml min−1 and a  of 240 ml min−1) and assuming that 20% of total blood flow goes to non-exercising tissues. See text for details.

of 240 ml min−1) and assuming that 20% of total blood flow goes to non-exercising tissues. See text for details.

Sensitivity of outcomes to mitochondrial respiration and muscle heterogeneity estimates in health

Recall that the three least well established determinants of O2 flux and partial pressures in the transport–utilization pathway are the  and P50 of the mitochondrial respiration curve (that links

and P50 of the mitochondrial respiration curve (that links  to mitochondrial

to mitochondrial  and the extent of muscle heterogeneity. Because of this, we carried out calculations of how variation in their assumed values would affect both

and the extent of muscle heterogeneity. Because of this, we carried out calculations of how variation in their assumed values would affect both  and mitochondrial

and mitochondrial  estimates. In this section, we now use (Fig.6) the four

estimates. In this section, we now use (Fig.6) the four  values stated in the Methods section that are 4.2, 4.6, 4.9 and 9.5 l min−1.

values stated in the Methods section that are 4.2, 4.6, 4.9 and 9.5 l min−1.

For mitochondrial P50 (assumed normal value 0.3 mmHg; Wilson et al. 1977; Gnaiger et al. 1998; Scandurra & Gnaiger, 2010), we also used values of 0.14 and 0.46 mmHg. With heterogeneity of  estimated at 0.1 (

estimated at 0.1 ( ), we also used values of 0.2 (moderate heterogeneity) and 0.3 (severe heterogeneity). This yielded 4 × 3 × 3 or 36 combinations of these variables. It should also be noted that the values chosen reflect substantial relative differences for each variable.

), we also used values of 0.2 (moderate heterogeneity) and 0.3 (severe heterogeneity). This yielded 4 × 3 × 3 or 36 combinations of these variables. It should also be noted that the values chosen reflect substantial relative differences for each variable.

Figure 6 shows the results of this analysis in a format where predicted  is plotted against the corresponding predicted average muscle mitochondrial

is plotted against the corresponding predicted average muscle mitochondrial  so that the effects can be seen for both of these outcome variables. The top panel shows results when

so that the effects can be seen for both of these outcome variables. The top panel shows results when  + 10%; the middle panel for

+ 10%; the middle panel for  + 20% and the lower panel for

+ 20% and the lower panel for  + 30%. In each panel, open squares represent P50 = 0.14 mmHg, filled circles a P50 = 0.3 mmHg and open triangles a P50 = 0.46 mmHg. For any one such P50, the three connected points in each case reflect, from left to right,

+ 30%. In each panel, open squares represent P50 = 0.14 mmHg, filled circles a P50 = 0.3 mmHg and open triangles a P50 = 0.46 mmHg. For any one such P50, the three connected points in each case reflect, from left to right,  = 0.1 (normal), 0.2 (moderate), and 0.3 (severe heterogeneity).

= 0.1 (normal), 0.2 (moderate), and 0.3 (severe heterogeneity).

In terms of predicted  , the consequences of these uncertainties are small. The highest

, the consequences of these uncertainties are small. The highest  in all three panels is 3415 ml min−1, and the lowest is 3192 ml min−1. However, in terms of mean mitochondrial

in all three panels is 3415 ml min−1, and the lowest is 3192 ml min−1. However, in terms of mean mitochondrial  , the effects are greater.

, the effects are greater.  is systematically higher for the lowest

is systematically higher for the lowest  (range of

(range of  : 0.8 to 3.7 mmHg, top panel) to lower panel (highest

: 0.8 to 3.7 mmHg, top panel) to lower panel (highest  , range of

, range of  : 0.3 to 1.9 mmHg).

: 0.3 to 1.9 mmHg).

In summary, the sensitivity analysis displayed in Fig.6 points out that at any  , increase in mitochondrial P50 results in systematically higher

, increase in mitochondrial P50 results in systematically higher  values with almost no effect on the relationship between

values with almost no effect on the relationship between  and

and  . On the other hand, increasing

. On the other hand, increasing  raises average

raises average  for any set of

for any set of  and P50 values. Moreover, the figure clearly indicates that the higher the

and P50 values. Moreover, the figure clearly indicates that the higher the  , the narrower is the range of potential mitochondrial

, the narrower is the range of potential mitochondrial  values for a given range of

values for a given range of  .

.

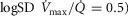

Simulated impact of lung and muscle heterogeneity on  and muscle

and muscle  in two patients with COPD of different severity: Question 4

in two patients with COPD of different severity: Question 4

As Table2 shows, lung heterogeneities had been measured in each patient using the multiple inert gas elimination technique (Blanco et al. 2010). The first patient displays features that would be regarded as reflecting moderate COPD, while the second patient represents end-stage COPD and extremely limited exercise capacity.

Figure 7 displays the impact of functional lung and muscle heterogeneities on the O2 pathway in the two COPD patients (moderate severity, left panels and end-stage severity, right panels). The format indicates the values of both predicted  and

and  over a range of values of the same three least certain variables (

over a range of values of the same three least certain variables ( and P50 of the mitochondrial respiration curve and degree of muscle

and P50 of the mitochondrial respiration curve and degree of muscle  heterogeneity, none of which are known for these patients).

heterogeneity, none of which are known for these patients).

Figure 7. Sensitivity analysis of mitochondrial respiration and muscle heterogeneity estimates in COPD.

Effects of muscle bioenergetics (mitochondrial respiration  and P50 parameters) and muscle peripheral heterogeneities on muscle

and P50 parameters) and muscle peripheral heterogeneities on muscle  and mitochondrial

and mitochondrial  (

( ) for given representatives of mild (left-side panels) and severe (right-side panels) limitation of O2 transport conditions in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

) for given representatives of mild (left-side panels) and severe (right-side panels) limitation of O2 transport conditions in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).  is conservatively taken as 10% (upper panels), 20% (middle panels) and 30% (lower panels) greater than measured

is conservatively taken as 10% (upper panels), 20% (middle panels) and 30% (lower panels) greater than measured  in the two COPD patients exercising maximally, selected as representatives of both mild and severe O2 transport conditions. For each

in the two COPD patients exercising maximally, selected as representatives of both mild and severe O2 transport conditions. For each  , three mitochondrial P50 values (0.14, 0.3 and 0.46 mmHg) and three degrees (0.1, 0.2 and 0.3) of muscle perfusion–metabolism inhomogeneity (

, three mitochondrial P50 values (0.14, 0.3 and 0.46 mmHg) and three degrees (0.1, 0.2 and 0.3) of muscle perfusion–metabolism inhomogeneity ( ) were evaluated. See text for details.

) were evaluated. See text for details.

The less affected patient (left three panels) behaves in a fashion very similar to that shown in Fig.6 for normal subjects (other than for absolute values of peak  under all conditions). In particular, mitochondrial

under all conditions). In particular, mitochondrial  values are in the same range as for normal subjects. Variation in

values are in the same range as for normal subjects. Variation in  across muscle regions is considerable (not shown) with a SD of 10 mmHg.

across muscle regions is considerable (not shown) with a SD of 10 mmHg.

For the severely affected patient (right three panels), peak  is insensitive to substantial changes in mitochondrial

is insensitive to substantial changes in mitochondrial  , P50 or the extent of heterogeneity. Only mitochondrial P50 changes will have some effect on mitochondrial

, P50 or the extent of heterogeneity. Only mitochondrial P50 changes will have some effect on mitochondrial  , but it is important to note that the scale of mitochondrial

, but it is important to note that the scale of mitochondrial  is very different than normal, and is far lower under all conditions, with little variation throughout the muscle (SD of 1 mmHg).

is very different than normal, and is far lower under all conditions, with little variation throughout the muscle (SD of 1 mmHg).

Discussion

Summary of major findings

This study has generated the first integrated model of the O2 pathway that takes into account all the individual components of O2 transport and utilization considering both exercising and non-exercising tissues at  in health and in disease (i.e. COPD), thus allowing for heterogeneity in both lungs and muscle. A graphical user interface to parameterize and simulate the integrative model is freely available at http://sourceforge.net/projects/o2pathway/.

in health and in disease (i.e. COPD), thus allowing for heterogeneity in both lungs and muscle. A graphical user interface to parameterize and simulate the integrative model is freely available at http://sourceforge.net/projects/o2pathway/.

The research addresses the separate and combined contributions of functional heterogeneities at pulmonary and at skeletal muscle levels to each of the components of the O2 pathway. Emphasis is placed on estimating the impact of lung and skeletal muscle  ratio inequalities on overall muscle

ratio inequalities on overall muscle  and on mitochondrial

and on mitochondrial  at maximal exercise. This was done simulating normal subjects at sea level and altitude, and patients with COPD.

at maximal exercise. This was done simulating normal subjects at sea level and altitude, and patients with COPD.

The main result from now allowing for lung and muscle heterogeneities is that heterogeneity in muscle affects O2 availability more than does heterogeneity in the lungs if  is only slightly higher than

is only slightly higher than  . However, if

. However, if  is greatly in excess of the potential to deliver O2, as small muscle mass studies suggest (Andersen & Saltin, 1985), the effects of lung and muscle heterogeneity are similar. On the other hand, the impact of lung heterogeneity on

is greatly in excess of the potential to deliver O2, as small muscle mass studies suggest (Andersen & Saltin, 1985), the effects of lung and muscle heterogeneity are similar. On the other hand, the impact of lung heterogeneity on  is insensitive to the

is insensitive to the  values used. In addition, because muscle heterogeneity appears to be less than that in the lung, muscle heterogeneity is predicted to have less of an impact on overall O2 transport and utilization than observed lung heterogeneity.

values used. In addition, because muscle heterogeneity appears to be less than that in the lung, muscle heterogeneity is predicted to have less of an impact on overall O2 transport and utilization than observed lung heterogeneity.

These findings stress the need for further measurements of skeletal muscle metabolism–perfusion heterogeneity in health and disease, and also of assessing parameters of the mitochondrial respiration curve ( and p50).

and p50).

Implications of functional heterogeneities: lung and skeletal muscle

Whether arterial oxygenation falls as a result of altitude in normal subjects or as a result of heterogeneity in the lungs in patients with lung disease (at sea level), it is clear that O2 availability to the muscles must fall. This has been appreciated for many years, as has the consequence of such reduced O2 availability for maximal exercise capacity. The other potentially important consequence of reduced O2 availability is reduced mitochondrial  . This may have more than one effect on cellular function.

. This may have more than one effect on cellular function.

While heterogeneity in the lungs must cause mitochondrial  to fall throughout the muscle (all other factors unchanged), heterogeneity in the muscles will additionally cause mitochondrial

to fall throughout the muscle (all other factors unchanged), heterogeneity in the muscles will additionally cause mitochondrial  to vary between muscle regions. In those areas with higher than average

to vary between muscle regions. In those areas with higher than average  in relation to blood flow, mitochondrial

in relation to blood flow, mitochondrial  is lower than average, but in regions where

is lower than average, but in regions where  is low in relation to blood flow, mitochondrial

is low in relation to blood flow, mitochondrial  must rise to levels greater than would be seen in the absence of heterogeneity. The consequences of subnormal mitochondrial

must rise to levels greater than would be seen in the absence of heterogeneity. The consequences of subnormal mitochondrial  are discussed below. There may be corresponding functional consequences of a high mitochondrial

are discussed below. There may be corresponding functional consequences of a high mitochondrial  as well.

as well.

A high  may oppose vasodilatation and restrict local perfusion, thus increasing the

may oppose vasodilatation and restrict local perfusion, thus increasing the  back towards normal and offering an intrinsic mechanism to automatically limit mitochondrial

back towards normal and offering an intrinsic mechanism to automatically limit mitochondrial  heterogeneity. A high mitochondrial

heterogeneity. A high mitochondrial  will also reduce the capillary-to-mitochondrial

will also reduce the capillary-to-mitochondrial  diffusion gradient, reducing diffusive O2 transport and again working towards restoring the balance between O2 supply and demand. Furthermore, the high

diffusion gradient, reducing diffusive O2 transport and again working towards restoring the balance between O2 supply and demand. Furthermore, the high  may exert genomic effects that may be opposite to those expected when

may exert genomic effects that may be opposite to those expected when  is below normal (see above). The potential therefore exists for regional regulation of gene expression (and thus for adaptive programs) according to local

is below normal (see above). The potential therefore exists for regional regulation of gene expression (and thus for adaptive programs) according to local  . Finally, when mitochondrial

. Finally, when mitochondrial  is elevated, the potential exists for increased ROS generation, just as when

is elevated, the potential exists for increased ROS generation, just as when  is below normal. If so, muscle regions with both very low and very high

is below normal. If so, muscle regions with both very low and very high  ratios may be at risk of oxidative stress.

ratios may be at risk of oxidative stress.

Biological and clinical implications

The multilevel impact of disturbances of cellular oxygenation on cell function is well recognized (Semenza, 2011). Hypoxia- (or hyperoxia-) induced biological alterations may play a significant role on underlying mechanisms in different acute and chronic conditions (Resar et al. 2005). A major conclusion of the present study is that mitochondrial  will vary considerably among muscle regions of different

will vary considerably among muscle regions of different  ratio. When

ratio. When  is low,

is low,  is high, and vice versa. This potential variation in

is high, and vice versa. This potential variation in  , which can occur during exercise in healthy individuals, but can also occur on submaximal exercise or even at rest in severe disease states, may have significant biological implications.

, which can occur during exercise in healthy individuals, but can also occur on submaximal exercise or even at rest in severe disease states, may have significant biological implications.

First, since a low  facilitates local vasodilatation in muscle (Rowell, 1986), those areas with high

facilitates local vasodilatation in muscle (Rowell, 1986), those areas with high  in relation to

in relation to  , thus having a low

, thus having a low  , may preferentially vasodilate, which means that

, may preferentially vasodilate, which means that  may increase locally and that the