Abstract

Molecular guided oncology surgery has the potential to transform the way decisions about resection are done, and can be critically important in areas such as neurosurgery where the margins of tumor relative to critical normal tissues are not readily apparent from visual or palpable guidance. Yet there are major financial barriers to advancing agents into clinical trials with commercial backing. We observe that development of these agents in the standard biological therapeutic paradigm is not viable, due to the high up front financial investment needed and the limitations in the revenue models of contrast agents for imaging. The hypothesized solution to this problem is to develop small molecular biologicals tagged with an established fluorescent reporter, through the chemical agent approval pathway, targeting a phase 0 trials initially, such that the initial startup phase can be completely funded by a single NIH grant. In this way, fast trials can be completed to de-risk the development pipeline, and advance the idea of fluorescence-guided surgery (FGS) reporters into human testing. As with biological therapies the potential successes of each agent are still moderate, but this process will allow the field to advance in a more stable and productive manner, rather than relying upon isolated molecules developed at high cost and risk. The pathway proposed and tested here uses peptide synthesis of an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-binding Affibody molecules, uniquely conjugated to IRDye 800CW, developed and tested in academic and industrial laboratories with well-established records for GMP production, fill & finish, toxicity testing, and early phase clinical trials with image guidance.

Keywords: surgery, guidance, fluorescence, emission, filter, luminescence, intervention, cancer, oncology, Affibody

1.0 INTRODUCTION

While oncologic surgery has always been guided by light, the limitations of visual white light guidance by eye or camera are well known, and so there has been a steady growth in research and development around the idea of augmenting surgical guidance with additional molecular-specific image information. The advance of molecular-guided surgery has been inhibited though by serious economic and scientific problems around development of accurate receptor-specific agents. In this paper, we outline an approach to advancing cell surface-receptor targeting fluorescent probes, in a manner which is designed to de-risk the process and allow fast evaluation of candidate compounds in clinical trial, facilitating translation into commercial adoption. The key steps in this work are design of the probe testing pathway which simplifies the required costs and utilizes specialized industry/academic expertise at each of the steps along the way.

Targeting specific oncologic expression of cell-surface receptors has long been considered to be a primary goal which would provide high specificity relative to the surrounding organ normal tissues. Yet while many agents have been tried in pre-clinical work, less than a handful of them have made it to clinical trials. This interest is partly fueled by the potential for using these immunologic targets for therapy as well as imaging, or for using the imaging to assess therapeutic efficacy. However, one of the major issues in receptor targeting is the limitation of very low concentration of receptors in vivo (nM levels), meaning that bound fraction signal levels can be potentially quite low. In fact, when therapeutic dose levels are injected (mM) then the bound fraction at the tumor cells can be orders of magnitude less than the free plasma and leakage concentrations, erasing the ability to see molecular binding. Instead administration of tracer doses is needed along with fast clearance of the unbound agent. Generally it is believed that for efficient molecular imaging a moderate affinity (Kd≅0.5-5nM) is needed coupled with a reasonably fast clearance time (τ≅0.25-4hrs), to allow bound agent to be visualized as the dominant signal in the tumor. However, a recent showed that high affinity, i.e. subnanomolar affinity, is needed if the target concentration is moderate or low (Tolmachev V. 2012, J Nucl Med, Jun; 53(6), 953-60). Affibody molecules have been shown to be good candidates in both pre-clinical and early clinical trials to match these demands. The concept of using fluorophore tagged Affibody molecules for surgical guidance at subpharmacologic doses is explored here as a way to target cell surface receptor expression in cancer.

Perhaps the largest practical barrier to development of molecular probes for surgical use is the financial limitation of developing and testing these agents in a business environment where few billing codes exist that can be applied. The creation of therapeutically directed contrast agents is an emerging paradigm, but has not yet reached strong success to encourage additional investment. As such, pilot scale trials of probes with well-known potential specificity are essential to advancing the field, because in the face of modest financial returns, few will invest in a molecular contrast agent with high risk of failure due to non-specificity, as is seen with many targeted therapeutics. In our proposed platform, an approach to reducing the up-front costs is explored with phase 0, microdose trial allowing FDA approval through the eIND pathway. The strengths and weaknesses and timeline of this are outlined here.

2.0 METHODS

2.1 Economic Issues and proposed model

In biological therapy production, there have been many cases of enormous investment followed by failures in clinical trials, leading to an economic climate where investment in new agents is becoming more and more conservative. Additionally, fluorescent molecular agents for imaging are not therapeutics and so the economic model for them is vastly different than therapeutics. Therapeutic agents can be used chronically and so individual usages can be in the dozens or hundreds of bottles, leading to large recuperation of revenue from investment. In comparison, diagnostic agents are typically only used one or perhaps up to four times per subject, and the costs must be tied with the imaging procedure, so revenue is typically 10-100x lower than therapeutics. This modest payback seriously limits commercial interest in diagnostic contrast agents. However surgical guidance is a high cost interventional procedure, so that accurate and useful molecular guidance from a contrast agent could be priced fairly highly if the procedure was truly paradigm changing. As such, there is a hope that molecular guided surgery could have reasonable economic reimbursement on the cost scale of the surgery itself (thousands of $), rather than on the cost scale of diagnostic imaging (hundreds of $), per procedure. Still the limitation of no existing molecular guided surgery paradigm limits the potential for current investment. The central economic hypothesis in this platform is that molecular guided surgery will become economically viable, but the development of the first few agents must be done at lower risk of economic failure. As such a pathway to develop and test new agents was developed which would limit cost and lower timeline for production and testing. Therefore if the agent testing is unsuccessful, the follow on costs for iteratively trying improved agents or altered methodologies is low and could be done within the cost structure possible in academically funded research. Thus the central goal of this work was to develop a paradigm which would be self-sustaining as a development framework for molecular guided surgery which will be supported by grant funding agencies and limited corporate investment. This way the process would help many in this field of development to find success.

Our proposed pathway was two pronged. First the proposed agent choice and production pipeline must be chosen such that the costs are feasible in an NIH grant mechanism, which is at most $500,000 per year for 5 years. So the absolute upper limit to available funding is $2.5million in direct costs. As such, it is easy to realize that biological production of antibodies through recombinant synthesis simply will never be developed within the current economics of this process. This is because recombinant production of humanized antibodies for a single run costs $2-4million itself just for the production run of gram sized quantities. Instead an economic path which is feasible is peptide synthesis, where individual molecules are built up through solid phase synthesis methods. The costs of these production runs are $100-$500 thousand for gram level quantities.

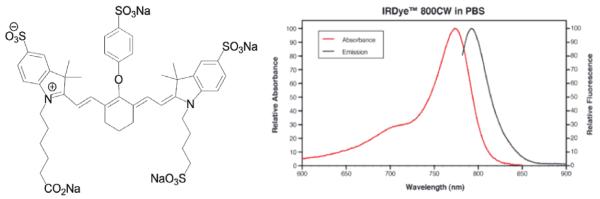

2.2 IRDye® 800CW as the bright emission, low toxicity NIR fluorescent reporter in human use

In order to be used in surgical guidance, the ideal wavelength band to use is 800nm emission to take advantage of the substantial penetration of this light in tissue, and also to utilize the technologies developed for indocyanine green fluorescence imaging (a vascular perfusion fluorescent tracer). In recent years, IRDye® 800CW has been advanced by LI-COR as a candidate for human use in tagging reporters. The combination of company interest, well established conjugation chemistry, superior stability, and high fluorescent yield makes this an ideal candidate for the molecular reporter.

While most trials have focused on product labeled with NHS ester chemical bond linkages to their biological agents, this approach leads to a range of binding sites on the active molecule, some of which compete with the intended binding site to the ligand. It is well known that if the dye can be bound through maleimide chemistry, then this would provide a site specific bond, leading to a consistent and well known conjugate product. The maleimide chemistry can be designed to work if the affibody molecules intended for use are produced with the needed site for binding.

Dozens of papers have been published showing examples of targeted fluorescence imaging with IRDye800CW [1]. For example, labeled human serum albumin (HSA) has been used for sentinel lymph node mapping [2] and surgical resection of spontaneous metastatic melanoma in a preclinical model. In other work, Trastuzumab was dual-labeled with 111In and IRDye800CW to detect HER2-expressing xenograft tumors [3] and Houston [4] compared gamma scintigraphy with NIR fluorescence imaging to illustrate that IRDye800CW provided greater signal to noise than the radiotracer 111In.

Toxicity testing of IRDye800CW carboxylate [5] was completed to help evaluate the tolerance of the naked dye, in male and female Sprague–Dawley rats using both IV and ID routes of administration. No pathological evidence was found of toxicity based upon hematologic, clinical chemistry, and histopathologic evaluations from doses of 1, 5, and 20 mg/kg. Similar toxicity testing on the IRDye800CW-maleimide will be completed as part of the proposed studies.

Additionally, an EGF-coupled IRDye 800CW has been studied extensively in rodents, and is commercially available for pre-clinical work. An Investigational Medicinal Product Dossier (IMPD) has been filed for the use of Bevicizumab labeled with IRDye800CW for imaging primary breast cancer at University Medical Center Groninigen in the Netherlands (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

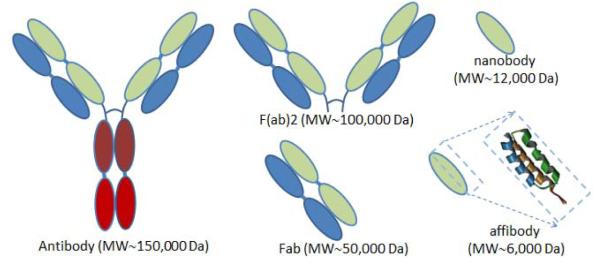

2.3 Targeting & Kinetics: High affinity & fast clearance of Affibody® molecules

Affibody molecules are an ideal candidate for testing in this paradigm, because Affibody AB has developed a group of these molecules which are small, single domain, non-immunoglobulin affinity ligands based on a 58 amino acid scaffold [6, 7]. The scaffold displays a three-alpha-helical bundle fold, and the target binding site is composed of 13 surface-exposed amino acids on helix 1 and helix 2. By randomizing these 13 amino acids, the company has created large libraries of Affibody® molecules from which binders to a given target protein are selected (examples include EGFR, HER2 or PDGFRß [8-10]). Their small size and stability, high affinity and target recognition specificity, rapid biodistribution kinetics and clearance make them ideal for in vivo targeting.

The ability of a HER2-binding Affibody molecule to visualize metastases has been demonstrated clinically in breast cancer patients by SPECT (111In) and PET (68Ga) imaging [11]. This first generation HER2-binding Affibody molecule was administered as [111In]ABY-002 or as [68Ga]ABY-002 for diagnostic imaging of HER2-expression. The administration of ~100 μg radiolabeled ABY-002 to three patients was well tolerated. More recently Affibody AB developed ABY-025, a HER2-specific Affibody molecule that targets a radionuclide to HER2-receptor expressing tumors for in vivo diagnosis of HER2-expressing cancer [12-14] which has been labeled with indium-111 for gamma camera detection and gallium-68 for PET imaging. Clinical data from 23 patients proved that ABY-025 imaging can distinguish HER2-positive from HER2–negative lesions (Sörensen, J. et al 2014, J Nucl Med 55: 730-735 and J. Sörensen, I. Velikyan, A. Wennborg, J. Feldwisch, V. Tolmachev, D. Sandberg, G. Nilsson, H. Olofsson, M. Sandström, M. Lubberink, J. Carlsson, H. Lindman; Measuring HER2-expression in metastatic breast cancer using 68Ga-ABY025 PET/CT EANM abstract OP298, Mo October 20, 2014).

Affibody molecules can be produced either by recombinant techniques in bacteria or by conventional peptide synthesis and can be readily modified with functional groups such as fluorescent or radioactive labels. Site specific modification of Affibody molecules is achieved by introducing a single cysteine which can be used for modification of maleimide-activated functional groups leading to defined and homogenous products [15]. Recently, the Affibody scaffold was further improved by rational design. The optimized scaffold has a surface distinctly different from that of its parent and is characterized by improved thermal and chemical stability, as well as increased hydrophilicity, and enables generation of identical Affibody molecules both by chemical peptide synthesis or recombinant bacterial expression [12]. Thus, these molecules can be tested quickly and efficiently by peptide sythesis production runs, and coupled with fluoresent agents.

2.4 Academic Partners for Conjugation, Analytics, Fill & Finish and Toxicology

Many such designs would focus on using a Clinical Research Organization (CRO) for the key stages of:

drug-dye conjugation to a drug substance,

analytical test development and production of a package for FDA,

fill and finish services into patient-ready vials for the drug product,

toxicology evaluation in animals.

However while this is commonly done the costs associated with these steps can be very high. Over time, academic centers have developed cost-effective methods for doing these steps, albeit in most cases not designed for testing beyond a phase 1 trial level. Still, when targeting a phase 0/1 trial, the developments can be completed in academic settings and the flexibility and moderate costs as compared to CRO organizations can make this a critically important decision.

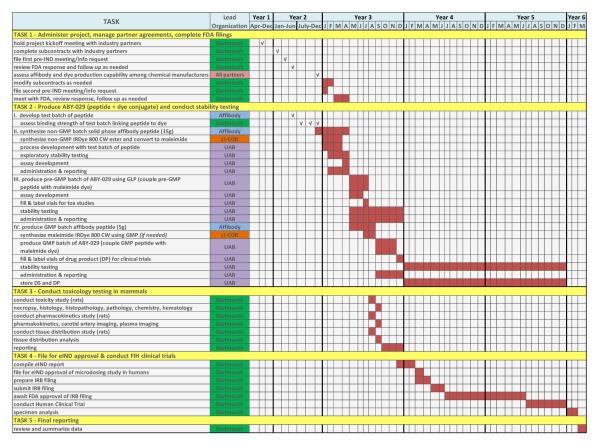

In this case, steps (i)-(iii) will be completed at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Vector Production Facility under cGMP conditions for Phase I drugs. The toxicity testing and evaluation is being completed at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College, in the Surgical Research Laboratories, under Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) procedures. Figure 4 illustrates the timeline for this process.

Figure 4.

Project timeline describing the partner’s responsibilities is shown and the dates for each task.

2.5 Testing Strategy: Phase 0 Trial as the goal

In our proposed solution, we target the little utilized phase 0 process at the Food & Drug Administration, and advance the use of medium molecular size agents which can take advantage of the lower costs of peptide synthesis for the development phase. As Table 2 shows, this first phase 0 process is designed to allow low dose testing of new agents, to assess pharmacokinetic efficacy without concern of significant pharmacologic effect, using injection of microdose values. The major benefit of this pathway is that when the trial is limited to microdose injection, then toxicity testing is limited to single animal species, typically rodents, and the scope of this species toxicity package is also limited.

Table 2.

Benefits and Limitations of Affibody development, by phase

| Phase of development | Pathway | Benefits | Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide synthesis | Subcontract to specialized supplier |

Low cost, low impurities, fast production timeline |

Large productions may not translate – further development may be required |

|

|

Labeling, Purification,

Analytical, Fill & Finish |

Academic partner | Low cost, flexibility in changes, fast timeline |

Limited to small production runs |

|

| Phase 0 Trial | Single species toxicity test | 2 week study | Low cost, fast timeline | Limits utility to phase 0 |

| eIND filing at FDA | Faster assessment of trial proposal at FDA |

Fast timeline | Limits utility to phase 0 |

|

| Microdose injection | <30nmol/human Fluorescence imaging to determine efficacy in localization |

Low drug dose, low risk for adverse events, fast trial, limited investment to assess localization. |

Fixed dose, no escalation, if successful needs to be followed by phase 1 |

|

2.6 Surgical utility: Neurosurgery

Reports of fluorescence-guided surgical resection first appeared more than 50 years ago when porphyrins were found to accumulate in tumors [16]; yet, intraoperative imaging systems have been developed largely around white light and surgeon vision. Nonetheless, visual assistance during surgery has become extremely sophisticated enabling microsurgical technique during procedures such as prostatectomy or neurosurgery through high-resolution, white-light microscopy. Robotic control in urological resection [17, 18] and as well as other surgical sites [19-23] is another emerging trend that, at least to date, is predominately predicated on the surgeon having visual access to the tissue of interest under white light exposure. Concurrently, Frangioni and colleagues have pioneered the use of fluorescence imaging in experimental surgery [24] based on a novel camera system and a platform of targeted compounds for surgical applications [25-28] in which the surgeon’s (white light) visual field is augmented with new information. Indeed, unlike other emerging technological enhancements in surgery, the opportunity for fluorescence is the intraoperative revelation of the biological margins of disease which cannot be visualized under white light (and are sufficiently microscopic to be unavailable through other forms of preoperative and intraoperative imaging).

Perhaps the largest clinical experience with fluorescence-guided resection has been gained in neurosurgery with aminolevulinic acid (ALA) induced protoporphyrin IX (PpIX). The approach has been evaluated in a prospective randomized Phase III trial [29] with sufficiently positive outcomes to alter standard-of-care in Germany for surgical resection of high grade gliomas and related studies are beginning to appear in the U.S. (several open protocols are now listed on clinicaltrials.gov) [30].

This experience makes neurosurgery an ideal setting in which to begin human studies with the proposed receptor-targeting fluorescent molecule for several compelling reasons. First, the specialty has historically been an early adopter of image guidance because surgical accuracy is paramount. As a result, commercially-available intraoperative imaging platforms have already been developed that can be readily used, adapted and compared. Further, the discipline has repeatedly served as a spring-board to broader surgical application of technical developments, principles and procedures that first appeared in neurosurgery. Second, open cranial access to tumor coupled with standard-of-care image guidance and concomitant coregistration with the surgical field provides the environment for specimen and image acquisition that is essential for validation of the diagnostic performance of new agents as biomarkers of disease. Third, brain tumors carry both the “difficult to treat” and “small market” labels which discourage commercial development and investment that our proposed Academic-Industrial Partnership is explicitly designed to overcome.

Here the plans are to begin with neurosurgery, as we find a number of scientific motivations for pursuing new brain tumor fluorescent probes beyond PpIX. For example, ALA-induced PpIX fluorescence is enhanced by non-tumor-specific molecular processes related to increased metabolism and blood-brain-barrier breakdown. Additional, glioma surgery can serve as the “proving ground” for testing the principles underpinning our platform. More importantly, the anti-EGFR molecule we propose to pursue is widely applicable to molecularly-based fluorescence-guided surgical oncology given the large number of tumors overexpressing EGFR summarized in Table 3, which is adapted from www.licor.com. Further, a wealth of information already exists on EGFR fluorophore targeting [31-40] which suggests that the approach is likely to be successful and could be applied to other surgical sites if the neurosurgical trial planned shows promise.

Table 3.

Fractions of tumors expressing EGFR

| Tumor Type | % over-expressing EGFR |

|---|---|

| Head & Neck | 80-100 % |

| Renal cell | 50-90 % |

| Glioma | 40-80 % |

| Ovarian | 40-50 % |

| Bladder | 35-70 % |

| Pancreatic | 30-50 % |

3.0 DISCUSSION

The pathways to success are not well established for molecular guided surgery, because it is not developed commercially. The closest paradigm is indocyanine green fluorescence guidance for vascular perfusion areas, which uses the same wavelength bands for excitation/emission, but since these procedures are device-agent combination therapies, FDA approvals need to be completed on both. As described the financial barriers to this are substantial, and the potential payback models are not well developed. As such, there is significant risk in developing new molecular-specific agents, and so this proposed pipeline pathway was developed to help advance the field and potentially move the proof of efficacy further along. The economics of the proposed pathway are sound and moderate cost, and significantly lower than biological therapeutic development.

The timelines for production, conjugation, purification, analytical package, stability testing, toxicology testing, and FDA evaluation and approval make for a long process. However small targeting proteins, with well-established methods for conjugation and testing combined with the goal of a phase 0 trial, are the keys to making this pathway fast and low cost. The proposal ongoing here involving a 5 way partnership with LI-COR, Affibody AB, University of Alabama Birmingham School of Medicine Vector Facility, Dartmouth College’s Thayer School of Engineering and the Geisel School of Medicine, is a good example of industry/academic partnership where key expertises are being utilized in a highly synergistic manner.

Molecular guidance of surgery sounds ideal, and while the reality is not proven, the potential is extremely attractive, and needs to be pursued, even in the current setting of limited commercial interest. If the process can be de-risked through development of both agents and customized systems for the procedures, then investment and clinical trials will follow.

Figure 1.

The comparison costs in money and time for a typical biological development and testing in a phase 1 trial are compared to the potential costs and timeline for a microdose trial designed for a phase 0 trial with an eIND pathway at the Food & Drug Administration. Note that the left column costs and timeline are high and lead to extreme financial risk, whereas the right column is manageable on a single NIH grant, and so significantly reduces risk.

Figure 2.

The structure of IRDye® 800CW (left) and absorption/emission spectra (right), used as the reporter for fluorescence. The excitation of this dye is often at 785nm, using diode laser light, and detection of emission at 800+ nm wavelengths is readily achieved with cameras designed for NIR detection.

Figure 3.

Receptor targeting proteins are largely based around the antibody structures discovered to binding uniquely to the receptors. The full antibody, antibody fragments, F(ab)2 or Fab, or nano bodies are all complex proteins which need to be produced through recombinant synthesis production methods. However the small binding domain of the Affibody molecule is a peptide sequence with less than 60 amino acids, and a 3 helical structure, which can be produced through solid phase peptide synthesis.

Table 1.

Affibody residence time

| Phase of agent in the body | Timescale | Problematic issues |

|---|---|---|

| Intravascular injection | 0-1 minute | Variations exist between subjects based upon physiology and injection accuracy |

| Perfusion & permeability in tumor | 0-3 minutes | Limited mainly by tumor perfusion |

| Diffusion through tumor | 1-5 minutes | Diffusion is fast in highly perfused tissues, but slower over longer distances (i.e. low capillary density) |

| Binding and retention in tumor | Minutes – hours dependent upon affinity |

Optimal affinity range depends upon injection concentration, receptor density & perfusion |

| Plasma clearance | Hours – days | Plasma clearance factors vary considerably between agents. Fast clearance is good for imaging, but limits delivery to tumor. A balance is needed. |

| Long term tumor clearance | Hours – days | As plasma level drops below tumor level, then clearance phase starts, and eventually the tumor clearance matches the timeline of the plasma clearance if perfusion is sufficient. |

4.0 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been funded from National Institutes of Health grant R01CA167413.

5.0 REFERENCES

- 1.Keereweer S, Kerrebijn JD, van Driel PB, Xie B, Kaijzel EL, Snoeks TJ, Que I, Hutteman M, van der Vorst JR, Mieog JS, Vahrmeijer AL, van de Velde CJ, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Lowik CW. Optical image-guided surgery--where do we stand? Mol Imaging Biol. 2011;13(2):199–207. doi: 10.1007/s11307-010-0373-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka E, Ohnishi S, Laurence RG, Choi HS, Humblet V, Frangioni JV. Real-time intraoperative ureteral guidance using invisible near-infrared fluorescence. J Urol. 2007;178(5):2197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sampath L, Kwon S, Ke S, Wang W, Schiff R, Mawad ME, Sevick-Muraca EM. Dual-labeled trastuzumab-based imaging agent for the detection of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 overexpression in breast cancer. J Nucl Med. 2007;48(9):1501–10. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.042234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Houston JP, Ke S, Wang W, Li C, Sevick-Muraca EM. Quality analysis of in vivo near-infrared fluorescence and conventional gamma images acquired using a dual-labeled tumor-targeting probe. J Biomed Opt. 2005;10(5):054010. doi: 10.1117/1.2114748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall MV, Draney D, Sevick-Muraca EM, Olive DM. Single-dose intravenous toxicity study of IRDye 800CW in Sprague-Dawley rats. Mol Imaging Biol. 2010;12(6):583–94. doi: 10.1007/s11307-010-0317-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nord K. A combinatorial library of an alpha-helical bacterial receptor domain. Protein Eng. 1995;8(6):601–608. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.6.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lofblom J, Feldwisch J, Tolmachev V, Carlsson J, Stahl S, Frejd FY. Affibody molecules: engineered proteins for therapeutic, diagnostic and biotechnological applications. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(12):2670–80. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman M, Orlova A, Johansson E, Eriksson TL, Hoiden-Guthenberg I, Tolmachev V, Nilsson FY, Stahl S. Directed evolution to low nanomolar affinity of a tumor-targeting epidermal growth factor receptor-binding affibody molecule. J Mol Biol. 2008;376(5):1388–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orlova A, Magnusson M, Eriksson TL, Nilsson M, Larsson B, Hoiden-Guthenberg I, Widstrom C, Carlsson J, Tolmachev V, Stahl S, Nilsson FY. Tumor imaging using a picomolar affinity HER2 binding affibody molecule. Cancer Res. 2006;66(8):4339–48. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindborg M, Cortez E, Hoiden-Guthenberg I, Gunneriusson E, von Hage E, Syud F, Morrison M, Abrahmsen L, Herne N, Pietras K, Frejd FY. Engineered high-affinity affibody molecules targeting platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta in vivo. J Mol Biol. 2011;407(2):298–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baum RP, Prasad V, Muller D, Schuchardt C, Orlova A, Wennborg A, Tolmachev V, Feldwisch J. Molecular imaging of HER2-expressing malignant tumors in breast cancer patients using synthetic 111In- or 68Ga-labeled affibody molecules. J Nucl Med. 2010;51(6):892–7. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.073239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldwisch J, Tolmachev V, Lendel C, Herne N, Sjoberg A, Larsson B, Rosik D, Lindqvist E, Fant G, Hoiden-Guthenberg I, Galli J, Jonasson P, Abrahmsen L. Design of an optimized scaffold for affibody molecules. J Mol Biol. 2010;398(2):232–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahlgren S, Orlova A, Wallberg H, Hansson M, Sandstrom M, Lewsley R, Wennborg A, Abrahmsen L, Tolmachev V, Feldwisch J. Targeting of HER2-expressing tumors using 111In-ABY-025, a second-generation affibody molecule with a fundamentally reengineered scaffold. J Nucl Med. 2010;51(7):1131–8. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.073346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahlgren S, Wallberg H, Tran TA, Widstrom C, Hjertman M, Abrahmsen L, Berndorff D, Dinkelborg LM, Cyr JE, Feldwisch J, Orlova A, Tolmachev V. Targeting of HER2-expressing tumors with a site-specifically 99mTc-labeled recombinant affibody molecule, ZHER2:2395, with C-terminally engineered cysteine. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(5):781–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.056929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orlova A, Tolmachev V, Pehrson R, Lindborg M, Tran T, Sandstrom M, Nilsson FY, Wennborg A, Abrahmsen L, Feldwisch J. Synthetic affibody molecules: a novel class of affinity ligands for molecular imaging of HER2-expressing malignant tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67(5):2178–86. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peck GC, Mack HP, Holbrook WA, Figge FH. Use of hematoporphyrin fluorescence in biliary and cancer surgery. Am Surg. 1955;21(3):181–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wexner SD, Bergamaschi R, Lacy A, Udo J, Brolmann H, Kennedy RH, John H. The current status of robotic pelvic surgery: results of a multinational interdisciplinary consensus conference. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(2):438–43. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Autorino R, Kim FJ. Urologic Laparoendoscopic Single-Site Surgery (LESS): current status. Urologia. 2011;78(1):32–41. doi: 10.5301/ru.2011.6448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horiguchi A, Uyama I, Ito M, Ishihara S, Asano Y, Yamamoto T, Ishida Y, Miyakawa S. Robot-assisted laparoscopic pancreatic surgery. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00534-011-0383-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rane A, Autorino R. Robotic natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery and laparoendoscopic single-site surgery: current status. Curr Opin Urol. 2011;21(1):71–7. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32833fd602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stuer C, Ringel F, Stoffel M, Reinke A, Behr M, Meyer B. Robotic technology in spine surgery: current applications and future developments. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2011;109:241–5. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-99651-5_38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hagen ME, Wagner OJ, Inan I, Morel P, Fasel J, Jacobsen G, Spivack A, Thompson K, Wong B, Fischer L, Talamini M, Horgan S. Robotic single-incision transabdominal and transvaginal surgery: initial experience with intersecting robotic arms. Int J Med Robot. 2010;6(3):251–5. doi: 10.1002/rcs.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pleijhuis RG, Langhout GC, Helfrich W, Themelis G, Sarantopoulos A, Crane LM, Harlaar NJ, de Jong JS, Ntziachristos V, van Dam GM. Near-infrared fluorescence (NIRF) imaging in breast-conserving surgery: assessing intraoperative techniques in tissue-simulating breast phantoms. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37(1):32–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Grand AM, Frangioni JV. An operational near-infrared fluorescence imaging system prototype for large animal surgery. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2003;2(6):553–62. doi: 10.1177/153303460300200607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vahrmeijer AL, Frangioni JV. Seeing the invisible during surgery. Br J Surg. 2011;98(6):749–50. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orcutt KD, Slusarczyk AL, Cieslewicz M, Ruiz-Yi B, Bhushan KR, Frangioni JV, Wittrup KD. Engineering an antibody with picomolar affinity to DOTA chelates of multiple radionuclides for pretargeted radioimmunotherapy and imaging. Nucl Med Biol. 2011;38(2):223–33. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gibbs-Strauss SL, Nasr KA, Fish KM, Khullar O, Ashitate Y, Siclovan TM, Johnson BF, Barnhardt NE, Tan Hehir CA, Frangioni JV. Nerve-highlighting fluorescent contrast agents for image-guided surgery. Mol Imaging. 2011;10(2):91–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orcutt KD, Ackerman ME, Cieslewicz M, Quiroz E, Slusarczyk AL, Frangioni JV, Wittrup KD. A modular IgG-scFv bispecific antibody topology. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2010;23(4):221–8. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzp077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stummer W, Pichlmeier U, Meinel T, Wiestler OD, Zanella F, Reulen HJ. Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(5):392–401. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70665-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts DW, Valdes PA, Harris BT, Fontaine KM, Hartov A, Fan X, Ji S, Lollis SS, Pogue BW, Leblond F, Tosteson TD, Wilson BC, Paulsen KD. Coregistered fluorescence-enhanced tumor resection of malignant glioma: relationships between delta-aminolevulinic acid-induced protoporphyrin IX fluorescence, magnetic resonance imaging enhancement, and neuropathological parameters. Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2011;114(3):595–603. doi: 10.3171/2010.2.JNS091322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leung K. IRDye 800-Labeled anti-epidermal growth factor receptor Affibody. 2004. [PubMed]

- 32.Chopra A. Cy5.5 conjugated anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody. 2004. [PubMed]

- 33.Leung K. IRDye 800CW-Epidermal growth factor. 2004. [PubMed]

- 34.Helman EE, Newman JR, Dean NR, Zhang W, Zinn KR, Rosenthal EL. Optical imaging predicts tumor response to anti-EGFR therapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10(2):166–71. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.2.12164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang K, Li W, Huang T, Li R, Wang D, Shen B, Chen X. Characterizing breast cancer xenograft epidermal growth factor receptor expression by using near-infrared optical imaging. Acta Radiol. 2009;50(10):1095–103. doi: 10.3109/02841850903008800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gleysteen JP, Newman JR, Chhieng D, Frost A, Zinn KR, Rosenthal EL. Fluorescent labeled anti-EGFR antibody for identification of regional and distant metastasis in a preclinical xenograft model. Head Neck. 2008;30(6):782–9. doi: 10.1002/hed.20782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koyama Y, Barrett T, Hama Y, Ravizzini G, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. In vivo molecular imaging to diagnose and subtype tumors through receptor-targeted optically labeled monoclonal antibodies. Neoplasia. 2007;9(12):1021–9. doi: 10.1593/neo.07787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barrett T, Koyama Y, Hama Y, Ravizzini G, Shin IS, Jang BS, Paik CH, Urano Y, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. In vivo diagnosis of epidermal growth factor receptor expression using molecular imaging with a cocktail of optically labeled monoclonal antibodies. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(22 Pt 1):6639–48. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kulbersh BD, Duncan RD, Magnuson JS, Skipper JB, Zinn K, Rosenthal EL. Sensitivity and specificity of fluorescent immunoguided neoplasm detection in head and neck cancer xenografts. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133(5):511–5. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.5.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenthal EL, Kulbersh BD, Duncan RD, Zhang W, Magnuson JS, Carroll WR, Zinn K. In vivo detection of head and neck cancer orthotopic xenografts by immunofluorescence. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(9):1636–41. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000232513.19873.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]