INTRODUCTION

Uterine serous carcinoma (USC) accounts for 3–5% of endometrial carcinomas and is the most common histologic type among type II endometrial carcinoma. It is characterized by high nuclear grade and papillary growth pattern and frequently is seen arising in a polyp with invasion into the polyp or endometrium with or without myometrial invasion. In contrast to patients with type I endometrial carcinoma, USCs more commonly occur in a background of atrophic endometrium, in relatively older women, and are more frequently associated with extrauterine disease (1). USC morphologically resembles serous ovarian, peritoneal, and fallopian tube carcinomas and shares a similar pattern of dissemination.

Even among women with USC that does not invade the myometrium, 33–50% harbor extrauterine disease when comprehensively staged (2). In one investigation, overall survival among stage I patients was 62.9% compared to 37.3% and 19.9% for stage III and IV, respectively (1). Similar to ovarian and other pelvic serous carcinomas, primary cytoreduction in advanced USC may be associated with improved outcomes (3–5).

High grade carcinomas of the ovaries, peritoneum, and fallopian tube represent overlapping diseases that share a similar molecular profile and may also share a common origin in the fallopian tube. The relationship of USC to these other high grade serous pelvic carcinomas is less clear. USCs frequently show alterations in ERBB2 (Her2/Neu), TP53, CDKN2A (p16), CDH1 (e-cadherin), as well as generalized loss of heterozygosity (6). Notably, inherited BRCA1 mutations may underlie some cases of USC, though at a lower rate than seen with ovarian, tubal, and peritoneal carcinomas (7).

USC is a high grade carcinoma of the endometrium with serous features that invade into the endometrial stroma. Endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma (EIC) is characterized by replacement of endometrial surface epithelium and glands by malignant cells that resemble invasive high-grade endometrial carcinoma (8). Thus, the cells in EIC appear histologically identical to those in USC, but there is no stromal invasion that characterizes carcinoma. In the fallopian tube, serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC) is comprised of cells showing marked atypia, such as nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromasia, high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, prominent nucleoli, and loss of polarity (9, 10). The majority of STIC demonstrate strong nuclear staining for p53 and the proliferative marker Ki-67 (10, 11).

Mutation of the tumor suppressor gene TP53 is the most frequent early genetic alteration in both uterine and other high grade serous pelvic carcinomas (6, 12, 13). p53 immunopositive foci in histologically normal epithelium (also called p53 signatures by some investigators) can be identified in benign-appearing epithelium of the fallopian tube or endometrium and may represent a precursor to pelvic serous carcinoma (10, 14). Previous studies have shown that p53 foci are more common in the tubal fimbria, which is thought to be the most common site of origin for tubal carcinomas, and have linked these foci to areas of DNA damage (14). Lee et al. found that multiple p53 foci were over twice as common in association with STIC relative to non-neoplastic tubal epithelium (67% vs 20–32%) (14). Interestingly, several studies have shown that p53 foci occur at a similar frequency in the fallopian tubes of women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations without neoplasia and “low risk” controls (14–16), though other studies have shown them to be more common in women with BRCA1 mutations after correction for the number of sections evaluated (17). Jarboe et al. hypothesized that endometrial p53 foci may represent a potential precursor to some cases of uterine serous carcinoma (18).

Studies of prophylactic oophorectomy specimens from women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations have shown higher than expected frequencies of early invasive serous carcinoma or STIC within the fallopian tubes. While earlier studies relying on a less formal pathological protocol identified occult carcinoma in approximately 2.5% of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, more recent studies show that rigorous systematic analysis at the time of risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) results in a rate as high of 5–10% (19–26). Medeiros et al. used the SEE-FIM [Sectioning and Extensively Examining the FIMbria] protocol to show that the fimbria were the most common location for invasive serous carcinoma and non-invasive STIC in a series of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers (27). STIC has been detected in 0–3% of controls, 8% of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers undergoing RRSO, and nearly 50% of cases of presumed ovarian or primary peritoneal serous carcinoma (16, 17, 19, 26, 28, 29). Furthermore, a high proportion of endometrial carcinomas with concurrent adnexal involvement (23%, 5 of 22 USC patients) had concurrent STIC (30), raising the question of whether the fallopian tube may be the site of origin of some uterine serous carcinomas.

Given the histologic and clinical similarities of USC and other pelvic serous carcinomas, we hypothesized that at least some portion of clinically diagnosed USC may actually originate in the fallopian tubes. Therefore, in order to better understand the origin of USC and clarify the relationship between USC and other pelvic serous carcinomas, we extensively evaluated the endometrium and fallopian tube epithelium in a series of USC for both neoplastic lesions and p53 foci.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

Case selection

Women diagnosed with USC at Mayo Clinic Rochester over a 5 year period were identified from an existing IRB-approved prospective tumor bank of patients with endometrial cancer. Inclusion criteria included pure serous histology and the availability of the entire bilateral fallopian tubes and uterus for evaluation. Exclusion criteria were cases with mixed histologies, gross adnexal involvement, or diffuse intraabdominal disease to minimize the chance the observed tubal epithelial changes were simply metastatic disease. Pure USC cases were selected as the cases most likely to support the hypothesis that a portion of USC originates from the fallopian tube.

Histological analysis

All original hematoxylin and eosin slides of the uterus, bilateral ovaries, and fallopian tubes were reviewed. Formalin fixed uteri and bilateral ovaries and fallopian tubes were retrieved from the Anatomic Pathology specimen archive. These specimens had undergone prior pathologic evaluation and, therefore, were not completely intact. The tissue was grossly evaluated by a pathologist (FM) and sectioned by a physician assistant (JLH). Bilateral ovaries, fallopian tubes, and non-neoplastic endometrium were grossly identified and entirely submitted for histopathologic evaluation. The fallopian tubes were sectioned using the SEE-FIM protocol [Sectioning and Extensively Examining the FIMbria] which included 3 mm cross sections and the fimbriae amputated and bivalved. Ovaries, previously bivalved, were cross-sectioned in 3 mm intervals. Perpendicular sections of the endometrium included the endometrial-myometrial interface. 28/38 (74%) of cases underwent complete surgical staging (total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH), bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO), bilateral pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy, and omentectomy) while another 6/38 (16%) underwent partial staging (TAH, BSO with bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy and/or omentectomy). The remaining 4/38 cases underwent TAH, BSO or total vaginal hysterectomy, BSO only.

All hematoxylin and eosin stained sections were examined by two pathologists with expertise in gynecologic pathology (FM and JFL) and evaluated for cytological and architectural atypia and the presence and extent of invasive and non-invasive neoplasia involving the endometrium, fallopian tubes, and ovaries. STIC of the fallopian tube was defined as severe cytological atypia including nuclear stratification and pleomorphism, associated with mitotic activity and loss of ciliae, which were confined to the epithelial layer without invasion of the lamina propria.

All sections of fallopian tube and non-neoplastic endometrium were examined for p53 expression by immunohistochemistry (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, clone DO-7). Antigen retrieval was performed using Antigen Unmasking Solution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame CA); the primary antibody reacted at 1:500 overnight at 4C. Antigen-antibody complexes were visualized using ImmPress Mouse (Vector), then 3,3'-Diaminobenzidine (DAB). p53 foci (also called p53 signatures) were defined as histologically benign-appearing epithelium that contained a stretch of at least 12 consecutive nuclei with strong p53 nuclear expression (14, 31).

RESULTS

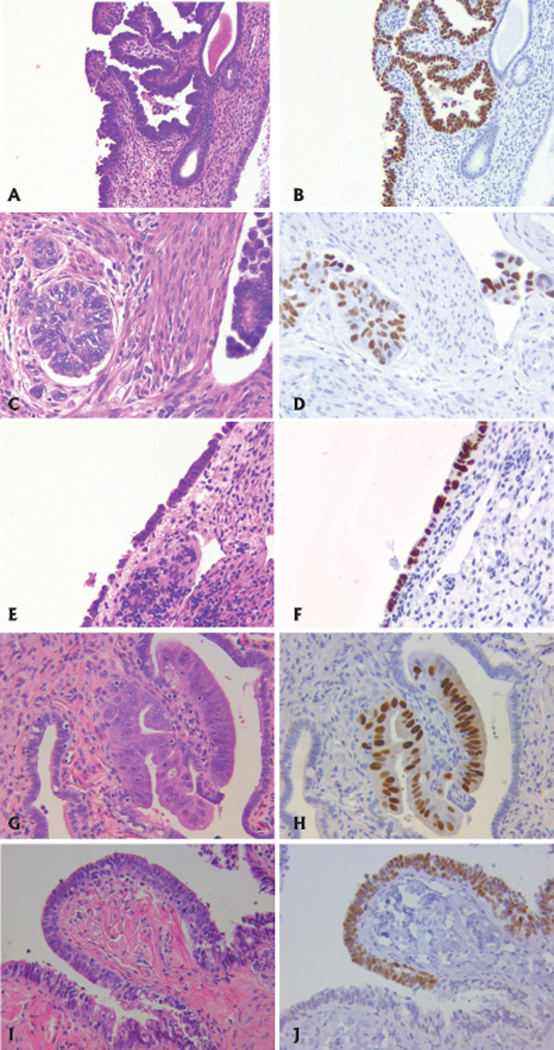

Thirty-eight cases of pure USC met inclusion criteria, the majority of which were invasive into the myometrium (32/38, 84%). Characteristics of the cohort are provided in Table 1. Concomitant areas of EIC were noted in 22 patients (58%, Figure 1). Non-atypical endometrial p53 foci were observed in 3 cases, ranging from 1–2 foci per case and 15–30 positive nuclei per focus (Figure 1). Two of the 3 cases with endometrial p53 foci had invasive carcinoma and EIC while 1 case had EIC only (USC was limited to an endometrial polyp).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| All patients, n=38 | # (% total) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Median (range) | 73 (45–91) | |

| Race | ||

| White | 34 (89.5) | |

| Unknown | 4 (10.5) | |

| Surgically staged | ||

| Complete* | 28 (73.7) | |

| Partial** | 6 (15.8) | |

| None | 4 (10.5) | |

| Stage | ||

| I | 18 (47.4) | |

| IA | 8 (21.1) | |

| IB | 10 (26.3) | |

| II | 2 (5.3) | |

| III | 11 (28.9) | |

| IIIA | 3 (7.9) | |

| IIIB | 0 | |

| IIIC1 | 3 (7.9) | |

| IIIC2 | 5 (13.2) | |

| IV | 7 (18.4) | |

| IVA | 0 | |

| IVB | 7 (18.4) | |

| Grade | ||

| Unknown | 1 (2.6) | |

| 1 | 1 (2.6) | |

| 2 | 1 (2.6) | |

| 3 | 35 (92.1) | |

complete indicates bilateral pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy and omentectomy

partial indicates bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy and/or omentectomy

only (not all percentages total to 100% due to rounding to 1 decimal place)

Figure 1.

Paired hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and p53 staining on endometrial and tubal tissues from women with uterine serous carcinoma. p53 immunostain is evident by the brown stain. A. H&E of EIC. B. p53 stain in EIC. C. Invasive USC. D. p53 stain in USC. E. Normal endometrial epithelium. F. p53 focus in normal endometrial epithelium. G. High grade intraepithelial neoplasia in fallopian tube epithelium. H. p53 stain of STIC in fallopian tube epithelium. I. Histologically normal fallopian tube epithelium. J. p53 focus in normal fallopian tube epithelium.

There were 11 cases (29%) with some type of neoplastic fallopian tube involvement (Table 2). In 9 of these 11 cases, we observed primarily tubal wall invasion or lymphatic involvement and, therefore, metastatic disease was the likely source. However, in 2 of these 11 cases only STIC was present, and a third case demonstrated both STIC and serous carcinoma. In one case with STIC, the coexisting USC did not invade the myometrium. Therefore, the rate of STIC in USC without other evidence suggesting metastatic spread was 2/38 (5.3%). All cases of STIC were in patients with stage III or IV disease (i.e. there were no cases of STIC in stage I or II cases). Only one case (case 1 in table 2) of tubal involvement was noted on the original pathological review.

Table 2.

Description of pathological findings of USC cases with neoplasia or p53 foci in the fallopian tubes.

| Case | Age | Stage | Grade | Myometrial invasion |

EIC present |

Adnexal involvement |

STIC present |

P53 foci present |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70 | IIIC2 | 3 | Yes | Yes | Tubal surface | No | No |

| 2 | 71 | IIIA | 3 | Yes | Yes | Tubal surface | No | No |

| 3 | 71 | IVB | 3 | No | No | Tubal invasion | No | No |

| 4 | 74 | IVB | 3 | Yes | No | Tubal surface | Yes | No |

| 5 | 75 | II | 3 | Yes | Yes | Tubal surface | No | No |

| 6 | 76 | IVB | 2 | Yes | Yes | Lymphatic spread | No | No |

| 7 | 79 | IIIC2 | 3 | Yes | No | Lymphatic spread | No | Tubal |

| 8 | 80 | IVB | 3 | Yes | No | Lymphatic spread | No | No |

| 9 | 91 | IIIC1 | 1 | Yes | No | Tubal invasion | No | No |

| 10 | 75 | IIIC1 | 3 | Yes | Yes | None | Yes | Tubal |

| 11 | 79 | IIIC2 | 3 | No | No | Ovary surface | Yes | No |

| 12 | 73 | IIIA | 3 | Yes | Yes | None | No | Tubal and endometrial |

Three patients had tubal p53 foci in morphologically normal epithelium (Table 2). One was associated with stage IIIC USC and had adnexal involvement with tubal lymphatic spread. The second was associated with stage IIIC USC and had associated STIC but no other adnexal neoplasia. In the third case of stage IIIA USC, the presence of the tubal p53 focus was not associated with STIC or other evidence of metastases. Within these tubal p53 foci, the number of foci ranged from 1–2 per case with 30–100 nuclei positive per focus.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we sought to characterize potential precursor lesions for USC in both the endometrium and fallopian tube by determining the prevalence of co-existing STIC and possible preneoplastic p53 foci. We observed that EIC is present in the majority of cases of USC, lending support to previous studies that EIC is a potential precursor lesion to USC (8, 32). Interestingly, isolated STIC without evidence of metastatic tubal involvement was present in 8% of USC cases, suggesting that the fallopian tube may be the site of origin for a minority of patients with USC. An alternative hypothesis would be that the fallopian tube lesions are separate primary lesions. The finding of both EIC and STIC in case #10 (Table 2) supports this alternative hypothesis. It would be interesting to know the germline genetic status of these cases to determine if those women with a tubal precursor lesion are more likely to have an inherited BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. It is known, however, that BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations are rare (<2%) in women with USC and no personal history of breast cancer (7).

Sherman et al. reported that EIC was present in 89% of uteri with USC compared with 6% of uteri with endometrial endometrioid carcinoma (33). Zheng et al. proposed a model for USC development in which carcinoma arises from resting endometrium manifesting first as p53 foci, then evolving to endometrial glandular dysplasia, then EIC, and finally to fully developed (invasive) serous carcinoma (34). While EIC was common in our study as well, endometrial p53 foci were surprisingly uncommon (8%) as compared to a previous report by Zhang et al. where 18/46 (39.1%) of USC cases, 6/16 (37.5%) of EIC cases, 2/60 (3.3%) of endometrioid endometrial cancer cases, and 1/60 (1.7%) of benign controls were found to have p53 foci (35). In the Zhang report, “p53 signatures” were defined by endometrial epithelial cells which were morphologically unremarkable but displayed diffuse and strong p53 nuclear staining. In their study of “p53 signatures”, defined as discrete segments of p53 positivity identified in morphologically benign glandular epithelium, Jarboe and colleagues identified “p53 signatures” in 7 of 10 cases of serous intraepithelial carcinoma involving polyps (18). Potential explanations for our lower rate of endometrial p53 foci include that we 1) limited our definition of p53 foci to those with at least 12 consecutive nuclei with strong p53 expression and 2) examined only grossly non-neoplastic appearing endometrium for p53 positivity.

Although, TP53 mutations are thought to be a crucial step in pelvic serous carcinogenesis, the biologic significance of our finding of tubal p53 foci is unclear as previously reported rates of tubal p53 foci in unaffected controls are higher (ranging from 19–50% (15–17, 36, 37)) than in our subjects with USC. However, previous controls have been significantly younger than the subjects in our series, possibly explaining the higher rate of tubal p53 foci in control subjects.

It is reported that up to two thirds of serous EIC may be associated with extrauterine disease and, therefore, could be considered synonymous with USC (34). A recent study by Roelofsen et al. suggested that EIC may represent the origin of some serous ovarian carcinomas by showing similar expression patterns of p53, Ki-67, and estrogen and progesterone receptors as well as TP53 mutations (38). Taken together, these data suggest that high grade serous intraepithelial neoplasia of either the fallopian tube or endometrium (endometrial EIC or STIC), may lead to what is eventually recognized as either uterine or ovarian serous carcinoma. On the other hand, the relatively low rate of fallopian tube p53 foci and STIC differentiates USC from high grade serous ovarian and fallopian tube carcinomas and argues against USC being the same entity as other pelvic serous carcinomas.

Examination of prophylactically removed fallopian tubes and ovaries from women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations has shown many instances of early serous carcinoma or STIC, the majority in the fimbriated end (19–27). Given the uncertainty of the neoplastic potential of p53 foci, STIC is the earliest accepted manifestation of serous carcinoma in the fallopian tube (9). Several recent studies have shown a 36% to 47% rate of STIC in ovarian and peritoneal serous carcinomas (19, 28, 29, 39), suggesting that a significant proportion of these cases originate in the fallopian tube. Furthermore, Kuhn et al. demonstrated an identical p53 mutation in STIC and primary peritoneal carcinoma in 27 of 29 cases (40), proving the common clonality of these synchronous lesions.

STIC was present in 8% of the USC cases we examined; our study excluded cases with gross evidence of adnexal or peritoneal disease to minimize the possibility of metastatic tubal involvement. Of note, Jarboe et al. previously reported a higher rate of STIC in USC, identifying STIC in 5 out of 22 (23%) (30). One possibility is that STIC is actually a metastatic implant, and this would be consistent with our finding of STIC only in stage III and IV USC despite the fact that over 50% of our cases were stage I or II (Table 1). On the other hand, the association of STIC with advanced stage disease in our cohort could also be explained by the synchronous spread of tubal neoplasia to the endometrium and to other metastatic sites (i.e. lymph nodes). However, it seems more likely that simultaneous spread to other organs would be associated with the development of tubal invasion, which was not observed. Jarboe et al. did not report the stage of their USC cases, or whether every case was surgically staged, but none of their 5 cases with STIC had other adnexal involvement and three were associated with USC in an endometrial polyp. Interestingly, in the Jarboe report, one subject with STIC and USC did have a family history of breast or ovarian cancer, though her genetic status was not reported. Evaluation of a large series of stage IA USC with complete staging and comprehensive serial sectioning of the fallopian tubes could help answer this question. A similar rate of STIC in early stage USC would provide stronger evidence that STIC is the originating lesion in a minority of cases.

The site of origin of pelvic serous carcinomas has by convention been based on the location where the bulk of tumor is identified. This creates a dilemma in cases with concurrent foci of carcinoma or intraepithelial neoplasia at multiple sites. Identifying the primary site with certainty has become increasingly important as we employ sophisticated molecular techniques to define the instigating events in carcinogenesis. Our data suggest that the fallopian tube may represent the primary lesion in a minority of cases of USC. Given that 11 of the 12 cases with adnexal involvement in our study were not identified at the time of original pathological examination, it may be worth discussing as an international/multidisciplinary group whether entirely submitting the bilateral fallopian tubes in cases of USC would be useful for the purposes of staging and prognosis.

Acknowledgments

FINANCIAL SUPPORT:

This work was supported by NIH grant R01CA131965 (EMS), the Wendy Feuer Ovarian Cancer Research Fund (EMS), NIH grant R01CA148747 (WAC), and the Mayo Comprehensive Cancer Center P30 CA15083 (SCD).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Slomovitz BM, Burke TW, Eifel PJ, et al. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC): a single institution review of 129 cases. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91(3):463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gehrig PA, Groben PA, Fowler WC, Jr, et al. Noninvasive papillary serous carcinoma of the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(1):153–157. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas MB, Mariani A, Cliby WA, et al. Role of cytoreduction in stage III and IV uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107(2):190–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Memarzadeh S, Holschneider CH, Bristow RE, et al. FIGO stage III and IV uterine papillary serous carcinoma: impact of residual disease on survival. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002;12(5):454–458. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2002.01149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grice J, Ek M, Greer B, et al. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: evaluation of long-term survival in surgically staged patients. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;69(1):69–73. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.4956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakkum-Gamez JN, Gonzalez-Bosquet J, Laack NN, et al. Current issues in the management of endometrial cancer. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(1):97–112. doi: 10.4065/83.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pennington KP, Walsh T, Lee M, et al. BRCA1, TP53, and CHEK2 germline mutations in uterine serous carcinoma. Cancer. 2013;119(2):332–338. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ambros RA, Sherman ME, Zahn CM, et al. Endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma: a distinctive lesion specifically associated with tumors displaying serous differentiation. Hum Pathol. 1995;26(11):1260–1267. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Folkins AK, Jarboe EA, Roh MH, Crum CP. Precursors to pelvic serous carcinoma and their clinical implications. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113(3):391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crum CP. Intercepting pelvic cancer in the distal fallopian tube: theories and realities. Mol Oncol. 2009;3(2):165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leonhardt K, Einenkel J, Sohr S, et al. p53 signature and serous tubal in-situ carcinoma in cases of primary tubal and peritoneal carcinomas and serous borderline tumors of the ovary. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2011;30(5):417–424. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e318216d447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jia L, Liu Y, Yi X, et al. Endometrial glandular dysplasia with frequent p53 gene mutation: a genetic evidence supporting its precancer nature for endometrial serous carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(8):2263–2269. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474(7353):609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee Y, Miron A, Drapkin R, et al. A candidate precursor to serous carcinoma that originates in the distal fallopian tube. J Pathol. 2007;211(1):26–35. doi: 10.1002/path.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folkins AK, Jarboe EA, Saleemuddin A, et al. A candidate precursor to pelvic serous cancer (p53 signature) and its prevalence in ovaries and fallopian tubes from women with BRCA mutations. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109(2):168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw PA, Rouzbahman M, Pizer ES, et al. Candidate serous cancer precursors in fallopian tube epithelium of BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Mod Pathol. 2009;22(9):1133–1138. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norquist BM, Garcia RL, Allison KH, et al. The molecular pathogenesis of hereditary ovarian carcinoma: alterations in the tubal epithelium of women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Cancer. 2010;116(22):5261–5271. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarboe EA, Pizer ES, Miron A, et al. Evidence for a latent precursor (p53 signature) that may precede serous endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2009;22(3):345–350. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlson JW, Jarboe EA, Kindelberger D, et al. Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: diagnostic reproducibility and its implications. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2010;29(4):310–314. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e3181c713a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callahan MJ, Crum CP, Medeiros F, et al. Primary fallopian tube malignancies in BRCA-positive women undergoing surgery for ovarian cancer risk reduction. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(25):3985–3990. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finch A, Shaw P, Rosen B, et al. Clinical and pathologic findings of prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomies in 159 BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100(1):58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kauff ND, Satagopan JM, Robson ME, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(21):1609–1615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rebbeck TR, Lynch HT, Neuhausen SL, et al. Prophylactic oophorectomy in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(21):1616–1622. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powell CB, Kenley E, Chen LM, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA mutation carriers: role of serial sectioning in the detection of occult malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(1):127–132. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powell CB, Chen LM, McLennan J, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) in BRCA mutation carriers: experience with a consecutive series of 111 patients using a standardized surgical-pathological protocol. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(5):846–851. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31821bc7e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamb JD, Garcia RL, Goff BA, et al. Predictors of occult neoplasia in women undergoing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(6):1702–1709. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medeiros F, Muto MG, Lee Y, et al. The tubal fimbria is a preferred site for early adenocarcinoma in women with familial ovarian cancer syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30(2):230–236. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000180854.28831.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kindelberger DW, Lee Y, Miron A, et al. Intraepithelial carcinoma of the fimbria and pelvic serous carcinoma: Evidence for a causal relationship. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(2):161–169. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213335.40358.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roh MH, Kindelberger D, Crum CP. Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma and the dominant ovarian mass: clues to serous tumor origin? Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(3):376–383. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181868904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jarboe EA, Miron A, Carlson JW, et al. Coexisting intraepithelial serous carcinomas of the endometrium and fallopian tube: frequency and potential significance. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2009;28(4):308–315. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e3181934390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jarboe E, Folkins A, Nucci MR, et al. Serous carcinogenesis in the fallopian tube: a descriptive classification. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008;27(1):1–9. doi: 10.1097/pgp.0b013e31814b191f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sherman ME, Bitterman P, Rosenshein NB, et al. Uterine serous carcinoma. A morphologically diverse neoplasm with unifying clinicopathologic features. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16(6):600–610. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199206000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sherman ME, Bur ME, Kurman RJ. p53 in endometrial cancer and its putative precursors: evidence for diverse pathways of tumorigenesis. Hum Pathol. 1995;26(11):1268–1274. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng W, Xiang L, Fadare O, Kong B. A proposed model for endometrial serous carcinogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(1):e1–e14. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318202772e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang X, Liang SX, Jia L, et al. Molecular identification of "latent precancers" for endometrial serous carcinoma in benign-appearing endometrium. Am J Pathol. 2009;174(6):2000–2006. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mehra KK, Chang MC, Folkins AK, et al. The impact of tissue block sampling on the detection of p53 signatures in fallopian tubes from women with BRCA 1 or 2 mutations (BRCA+) and controls. Mod Pathol. 2011;24(1):152–156. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saleemuddin A, Folkins AK, Garrett L, et al. Risk factors for a serous cancer precursor ("p53 signature") in women with inherited BRCA mutations. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111(2):226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roelofsen T, van Kempen LC, van der Laak JA, et al. Concurrent endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma (EIC) and serous ovarian cancer: can EIC be seen as the precursor lesion? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22(3):457–464. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182434a81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seidman JD, Zhao P, Yemelyanova A. "Primary peritoneal" high-grade serous carcinoma is very likely metastatic from serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: assessing the new paradigm of ovarian and pelvic serous carcinogenesis and its implications for screening for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;120(3):470–473. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuhn E, Kurman RJ, Vang R, et al. TP53 mutations in serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma and concurrent pelvic high-grade serous carcinoma--evidence supporting the clonal relationship of the two lesions. J Pathol. 2012;226(3):421–426. doi: 10.1002/path.3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]