Abstract

Binge drinking is a common form of alcohol abuse that involves repeated rounds of intoxication followed by withdrawal. The episodic effects of binge drinking and withdrawal on brain resident cells are thought to contribute to neural remodeling and neurological damage. However, the molecular mechanisms for these neurodegenerative effects are not understood. Ethanol (EtOH) regulates the metabolism of ceramide, a highly bioactive lipid that is enriched in brain. We used a mouse model of binge drinking to determine the effects of EtOH intoxication and withdrawal on brain ceramide metabolism. Intoxication and acute alcohol withdrawal were each associated with distinct changes in ceramide regulatory genes and metabolic products. EtOH intoxication was accompanied by decreased concentrations of multiple ceramides, coincident with reductions in the expression of enzymes involved in the production of ceramides, and increased expression of ceramide degrading enzymes. EtOH withdrawal was associated with specific increases in ceramide C16:0, C18:0 and C20:0 and increased expression of enzymes involved with ceramide production. These data suggest that EtOH intoxication may evoke a ceramide phenotype that is neuroprotective, while EtOH withdrawal results in a metabolic shift that increases the production of potentially toxic ceramide species.

Introduction

Alcohol is a commonly abused drug, and the neurotoxic effects of ethanol (EtOH) abuse are well documented. Episodic or “binge” drinking involves the consumption of EtOH over a short period of time with the intent of intoxication, and is defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism as the intake of 4 (females) or 5 (males) drinks (1 oz of absolute alcohol) over a short period of time. Intoxication is followed by acute withdrawal and some period of absence before the next episode of binge drinking. Binge drinking is a common form of alcohol intake among young adults, with approximately 44.4% of college students reporting binge alcohol use (Wechsler et al. 2002). In general, alcohol abuse is associated with adverse neurologic outcomes and neurocognitive damage that is manifest by the dysregulation of neural networks involved with frontoparietal executive control, and midbrain networks associated with attention (Crews et al. 2004, Jacobus & Tapert 2013, Pfefferbaum et al. 2001, Muller-Oehring et al. 2013, Sullivan et al. 2005). Binge drinkers are at higher risk for neurocognitive impairments compared with chronic alcohol users, possibly due to more profound degenerative effects in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex that result from repeated cycles of intoxication and withdrawal (Hunt 1993, Zahr et al. 2013, Obernier et al. 2002, Corso et al. 1998, Collins et al. 1998, Zou et al. 1996, Elibol-Can et al. 2011, Zahr et al. 2010). Despite a wealth of data on neurocognitive and neuropathological effects of binge drinking, very little is known about the underlying molecular mechanisms of neural dysfunction and damage.

EtOH has been shown to regulate ceramide metabolism, a bioactive lipid that is enriched in brain. In cultured neurons, prolonged EtOH exposure was associated with increases in triglycerides, ceramides, and reductions in neuron viability (Saito et al. 2005). Inhibition of serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT; the rate limiting enzyme in de novo ceramide synthesis) protected neurons from the toxic effects of EtOH in tissue culture (Saito et al. 2005), suggesting that ceramide is connected to neuronal cell damage induced by EtOH. Similar results were found in cultured astrocytes where ETOH-induced death involved the formation of ceramide and induction of stress-associated kinases (Pascual et al. 2003). However, a mechanistic explanation for the effect of EtOH on ceramide in astrocytes implicated the catabolism of SM to ceramide by acid and neutral sphingomyelinse (Pascual et al. 2003). Thus, the effects of EtOH on ceramide metabolism in neurons and astrocytes may involve the induction of cell-specific metabolic pathways. The involvement of ceramide in EtOH-induced neural damage has also been suggested in experiments with young mice where EtOH exposure increased immunostaining for SPT and an activated form of the pro-apoptotic protein caspase 3 (Saito et al. 2007, Saito et al. 2010). These findings suggest that ceramide formation may be a critical step in EtOH-associated neurodegeneration. However, EtOH exposure in young mice has also been shown to regulate sphingosine kinase 2 and increased brain levels of sphingosine 1-phosphate (SIP), a metabolic product of ceramide with protective and trophic effects (Chakraborty et al. 2012). These acute effects of EtOH were followed by caspase 3 activation 8 h after EtOH (Chakraborty et al. 2012), suggesting that the effects of EtOH on ceramide metabolism may produce both protective and toxic lipid species depending on the intoxicating vs. withdrawal effects of EtOH. In this study we sought to define the temporal effects of binge EtOH consumption on brain ceramide metabolism in a model of binge drinking.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male C3-C57B1/6J mice 8 weeks of age, weighing 25-30 g obtained from Jackson laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine) were used for this study. Animals were single housed in a temperature and humidity controlled room under a 12 hr reverse light cycle. Animals were allowed to acclimate to the colony room for at least 7 days after arrival. Food and water was available ad libitum. All animal procedures, which were consistent with American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care guidelines, were reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Binge consumption of EtOH and EtOH withdrawal

Binge drinking of alcohol was conducted using a procedure modified from Rhodes (Rhodes et al. 2005). EtOH (Sigma, 200 proof, ≥ 99.5%) was diluted to 20% (v/v) in sterile water and administered in water bottles for 3 h each of 5 consecutive days beginning 2 h into the animals dark cycle. Water bottles were pre-tested to ensure they did not leak, and consumption was determined by water weight before and after administration. The amount of EtOH intake was recorded for each day after the 3 h drinking period. Vehicle controls were given water in the similar containers as mice who received alcohol and they were handled in same manner as mice exposed to alcohol. Immediately following the final binge drinking period, half of the mice were sacrificed (n=5 EtOH, and n=5 water), and half were scarified 6 h later (n = 5 EtOH, and n=5). These time periods were chosen to reflect intoxication (based on amount of alcohol consumed) and withdrawal (based on alcohol metabolism in the mouse)(Pastino et al. 1996).

Mass spectrometric measurement of ceramides and sphingomyelins

Total lipid content was extracted from freshly frozen cortex using a modified Bligh and Dyer procedure (Bandaru et al. 2007). Each tissue sample was weighed and homogenized at room temperature in deionized water (10 volumes to weight). To this mixture ethanol containing 53 mM ammonium formate (3 volumes) and the internal standards C12:0 ceramide and C12:0 sphingomyelin (17 ng/ml each) were added, and vortexed followed by the addition of chloroform (4 volumes) to separate lipid content. The mixture was vortexed and centrifuged at 1,000 g for 10 min. The chloroform layer was removed, dried in a vacuum dryer, and stored at −20°C. Samples were resuspended in 100% methanol for analysis by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization/multi-stage mass spectrometry LC/ESI/MS/MS. All extractions were performed using borosilicate-coated glass tubes, pipettes, and injectors to reduce the potential loss of lipids through interaction with plastic. ESI/MS/MS analyses were performed using methods similar to those used in previous studies (Bandaru et al. 2007, Haughey et al. 2004). Individual molecular species of sphingomyelin and ceramide (C12:0 and C16:0-C26:1) were detected and quantified by LC/MS/MS using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM). The procedure is based on high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) for temporal resolution of compounds with subsequent introduction into the mass spectrometer for detection and quantification by mass/charge. Samples were injected using a PAL autosampler into a PerkElmer HPLC equipped with a 2.6 μm, C18, 100 Å 50Å~2.1 mm column for ceramides and a 5 μm, C18, 100 Å 100Å~2 mm column for sphingomyelins (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). The sample was eluted at 0.4 mL min−1 for ceramides and 1 ml min−1 for sphingomyelins. The LC column was first pre-equilibrated for 0.5 min with the first mobile phase consisting of 85% methanol, 15% H20, and 5 mM ammonium formate. The column was then eluted with the second mobile phase consisting of 99% methanol, 1% formic acid, and 5 mM ammonium formate. The eluted sample was injected into the ion source, and the detection, and quantification of each analyte was carried out by ESI/MS/MS in MRM mode, monitoring the parent compound and products by ion scan. Method development for the quantitative detection of each analyte was accomplished with the aid of reference standards for sphingomyelins and ceramides from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Slight differences in extraction or mass spectrometer efficiencies were normalized using internal standards (ceramide C12:0 and sphingomyelin C12:0) with molecular structures similar to the analytes but not found in mammals. Area under the curve for each analyte was defined individually using the Analyst 1.4.2 software package.

Measurement of RNA expression for enzymes involved in sphingolipid metabolism

Total RNA was isolated from cortex for each set of experimental conditions using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc.). cDNA was synthesized using total RNA, N6 random primers and SuperScriptII Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). cDNA was then mixed with RNase free water, gene specific primers, primers for β-actin (an internal control), 2X PCR universal master mix (Applied Biosystems, Inc.), and amplified using an ABI 7500 Real Time PCR system following the manufacturer's directions. The gene specific primers used in this study were Longevity assurance homolog1-6 (Lass1-6, also known as ceramide synthase 1-6) (Applied Biosystems Cat# Hs04195319_s1, Hs00371958_g1, Hs00698859_m1, Hs00226114_m1, Hs00332291_m1, Hs00826756_m1), sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase1-4 (SMPD1-4; Applied Biosystems Cat# Hs03679347_g1, Hs00162006_m1, Hs00920354_m1, Hs04187047_g1), alkaline ceramidase1-3 (ACER1-3; Applied Biosystems Cat# Hs00370322_m1, Hs01892094_g1, Hs00218034_m1), acid ceramidase 1 and 2 (ASAH1, 2; Applied Biosystems Cat# Hs00602774_m1, Hs01015655_m1), sphingomyelin synthase 1, 2 (SGMS1-2; Applied Biosystems Cat# Hs00983630_m1, Hs00380453_m1), sphingosine kinase 1, 2 (SPHK1-2; Applied Biosystems Cat# Hs00184211_m1, Hs00219999_m1). The relative levels of gene expression were calculated using the ΔΔCt method by normalization to the internal control β-actin.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA), and the results presented as mean ± S.D. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post hoc tests was used for group comparisons. A statistically significant difference was considered as p < 0.05 or better.

Results

Drinking behavior

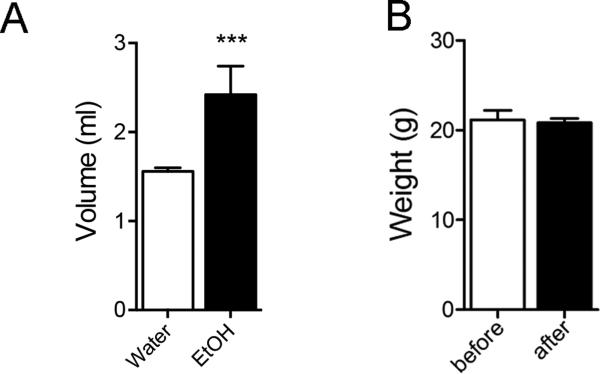

Drinking behavior over a 3 h period was recorded each day for a total of 5 days. Mice who received 20% EtOH in their drinking water consumed a larger volume during the 3 h exposure periods compared with mice that received only water (Figure 1A). One week of daily EtOH binge exposure did not alter body weight (Fig1B).

Figure 1. Binge EtOH consumption did not alter body weight.

A) Water or EtOH (20% v/v) consumption during a 3 h period that began 2 h into the animals dark cycle. B) Body weight recorded before and after 5 consecutive days of binge EtOH intake. Data are mean ± S.D. of n = 5 group. *** = p < 0.001 compared to water. ANOVA with Tukey post hoc comparisons.

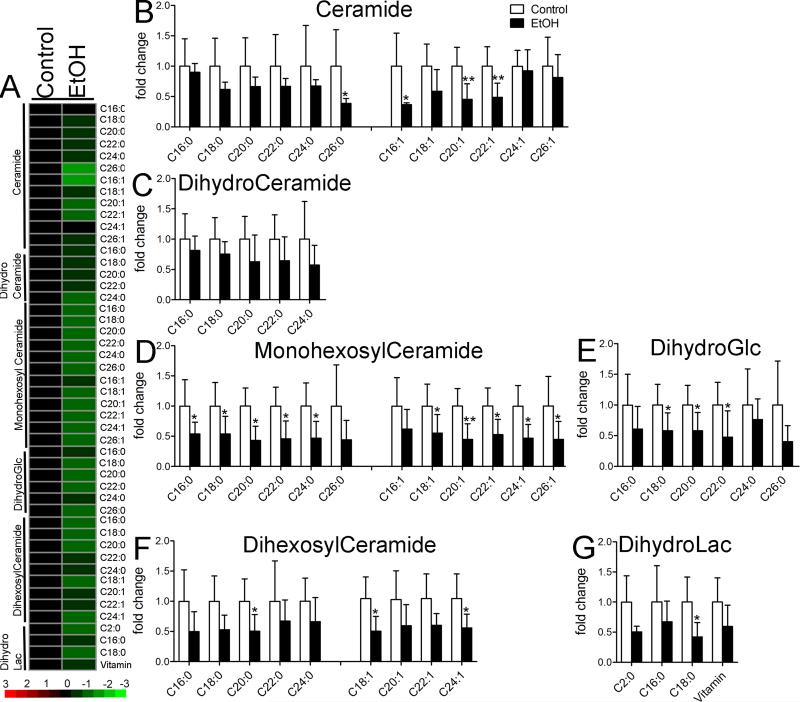

Ethanol binge drinking reduced concentrations of brain ceramides

Ceramide profiles were determined in frontal cortex of mice sacrificed immediately following binge EtOH drinking. Ceramides were categorized into six classes that consisted of ceramide, dihydroceramide, monohexosylceramide, dihexosylceramdie, dihydroglycosylceramide, and dihydrolactosylceramide. Each class of ceramides was then sub-classified by chain length and saturation. EtOH binge drinking resulted in an overall reduction of ceramides compared with mice not exposed to EtOH (Figure 2A; F=161.8, p < 0.0001, ANOVA). When grouped by ceramide class, binge drinking resulted in reductions of the very long-chain ceramide C26:0, and several monounsaturated species that included, C16:1, C18:1, C20:1, and C22:1 (Figure 2B). Although there was a trend for reductions in dihydroceramides (Figure 2C; F=8.812, p = 0.0044, ANOVA), none of the individual dihydroceramide species reached significance (Figure 2C). The largest effect of binge alcohol was manifest by reductions in a variety of complex ceramides including monohexosylceramides (Figure 2D), dihexosylceramide (Figure 2E), dihydroglycosylceramide (Figure 2F), and dihydrolactosylceramide (Figure 2G). These data suggest that repetitive binge drinking produces reductions in simple and complex cortical ceramides.

Figure 2. Ceramide species in cortex during binge EtOH intoxication.

A) Heat map showing relative fold changes for the indicated ceramide species following 3 h of binge EtOH as compared to control. Green color depicts decreased, and red depicts increased compared to control. Brighter color reflects fold change as indicated by the legend. Quantitative analysis of B) ceramide, C) dihydroceramide D) monohexosylceramide, E) dihydroglucosyl ceramide, F) dihexosylceramide and G) dihydrolactosylceramide species are shown for the indicated acyl chain lengths, and degree of saturation. n = 5 group. * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001 compared to control. ANOVA with Tukey post hoc comparisons.

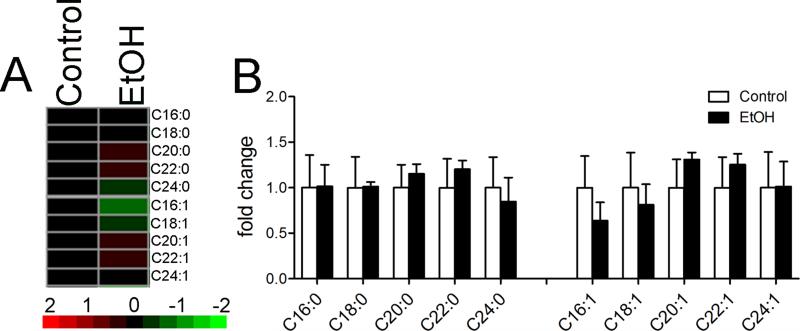

EtOH binge drinking did not have an overall effect on concentrations of any sphingomyelin tested (Figure 3A; F=0.2, p = 0.6535, ANOVA), and did not alter concentrations of individual class or sub-class of sphingomyelins based on chain length and saturation (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Sphingomyelin levels during binge EtOH intake.

A) Heat map showing the relative fold changes for the indicated sphingomyelin species in cortex following a 3 h exposure to binge EtOH intake. Green color depicts decreased, and red depicts increased compared to control. Brighter color reflects fold change as indicated by the legend. B) Quantitative analysis of the indicated sphingomyelin species separated by acyl chain length and saturation. n = 5 group. ANOVA with Tukey post hoc comparisons.

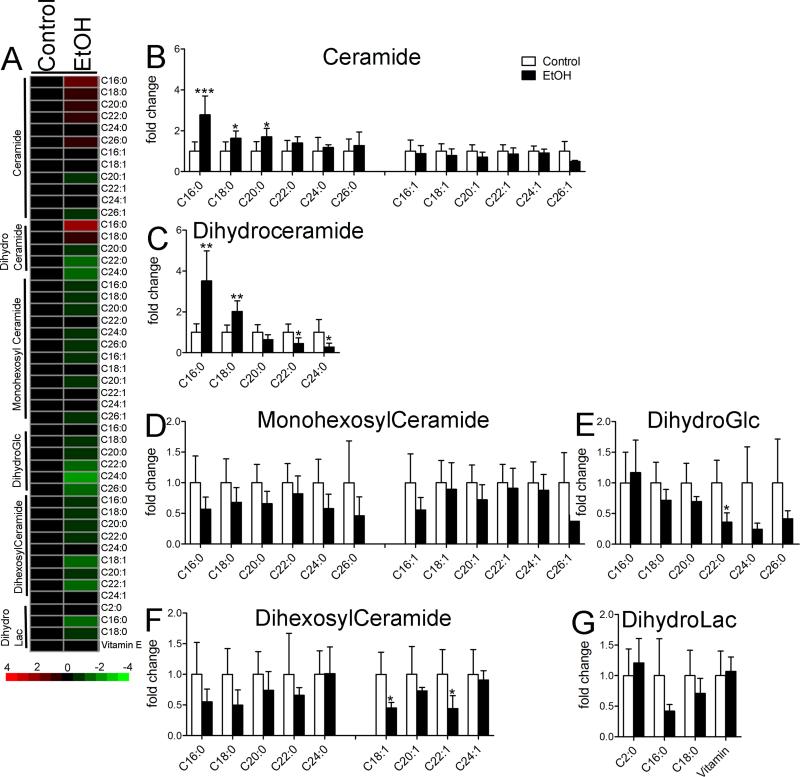

Ceramide concentrations were increased over baseline during acute ethanol withdrawal

Profiles of ceramides were characterized in the frontal cortex 6h following the binge intake of EtOH. During this acute withdrawal period there were specific rebounds of long chain ceramides C16:0, C18:0, and C20:0 above control levels. The very long-chain C24:0 and C26:0, and all monounsaturated ceramides returned to levels not different from controls (Figure 4A, B). Long-chain dihydroceramides were also increased during the acute withdrawal period, but the very long-chain dihydroceramides C22:0, and C24:0 were decreased (Figure 4C). Dihydroceramides are immediate precursors to ceramides in the de novo synthetic pathway, suggesting induction of this pathway during acute withdrawal. Complex ceramides were largely normalized during acute withdrawal. All individual species of monohexosylceramide returned to levels not significantly different from water fed controls during EtOH withdrawal (Figure 4D). However, concentrations of dihydroglycosylceramids dihexosylceramides, and dihydrolactosylceramide appeared to only partially normalize during acute withdrawal (Fig 4E-G). These data suggest that metabolic pathways regulating the production of simple ceramides are highly reactive to EtOH withdrawal, while pathways regulating the production of more complex ceramides react slowly.

Figure 4. Ceramide levels in cortex during acute EtOH withdrawal.

A) Heat map showing relative fold changes for the indicated ceramide species in cortex. Green depicts decreased, and red depicts increased compared to control. Color intensity reflects fold change as indicated by the legend. Quantitative analysis of B) ceramide, C) dihydroceramide D) monohexosylceramide, E) dihydroglucosyl ceramide, F) dihexosylceramide and G) dihydrolactosylceramide species are shown for the indicated acyl chain lengths, and degree of saturation. n = 5 group. * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001 compared to control. ANOVA with Tukey post hoc comparisons.

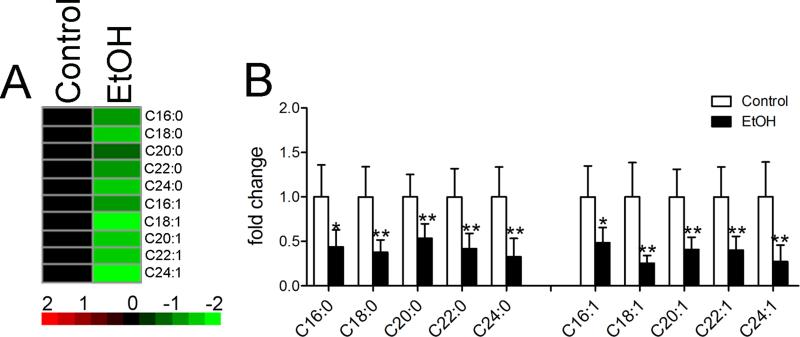

The overall effect of EtOH withdrawal was to reduce sphingomyelin levels (Figure 5A; p < 0.0001, ANOVA). The comparisons for each sphingomyelin species showed that EtOH withdrawal resulted in a reduction of all saturated and monounsaturated sphingomyelin species (Figure 5B). Sphingomyelin can be hydrolyzed to ceramide under conditions of stress, suggesting that this catabolic pathway may have also contributed to increases of long-chain ceramides during acute withdrawal.

Figure 5. Sphingomyelin levels in cortex during acute EtOH withdrawal.

A) Heat map showing the relative fold changes for the indicated sphingomyelin species 6 h following the cessation of binge EtOH intake. Green depicts decreased, and red depicts increased compared to control. Brighter color reflects fold change as indicated by the legend. B) Quantitative analysis of the indicated sphingomyelin species separated by acyl chain length and saturation. n = 5 group. ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001 compared to control. ANOVA with Tukey post hoc comparisons.

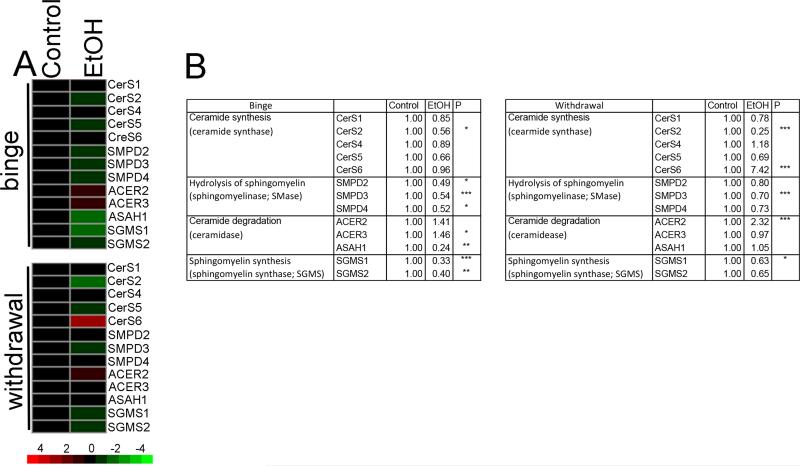

Binge drinking and acute withdrawal differentially modulate the expression of enzymes involved in ceramide metabolism

We next determined if binge drinking or withdrawal modified gene expression of 13 genes involved in sphingolipid metabolism (Fig. 6A). Binge intoxication decreased expression of ceramide synthase 2 (p < 0.05), and several forms of sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 2 SMPD2 (p < 0.05), SMPD3 (p < 0.001), and SMPD4 (p < 0.05). There were mixed changes in expression of enzymes that cleave fatty acids from ceramide to produce sphingosine. Alkaline ceramidase 3 expression was increased (ACER3, p < 0.05), but acid ceramidase 1 expression was decreased (ASAH1, p < 0.01) in response to binge drinking. Both known sphingomyelin synthases (SGMS1, p < 0.001 and SGMS2, p < 0.01) were decreased during binge intoxication (Fig. 6A, B). This expression pattern is consistent with decreases in ceramide and sphingomyelin observed during binge drinking.

Figure 6. Sphingolipid metabolic pathway gene expression.

A) Heat map showing the relative fold change for the indicated genes during binge and acute withdrawal conditions. Ceramide synthase 1-6 (CerS1-6), sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase2-4 (SMPD2-4), alkaline ceramidase2,3 (ACER2,3), acid ceramidase (ASAH1), sphingomyelin synthase 1, 2 (SGMS1, 2). B) Quantitative analysis of fold change for the indicated genes compared to control. * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001 compared to control. ANOVA with Tukey post hoc comparisons.

Acute withdrawal resulted in a trend towards normalization of gene expression, with the exception of ceramide synthases that were unaltered or increased during this time period. During acute withdrawal ceramide synthase expression remained decreased, and CerS2 was further decreased (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6A, B). However, there was a large increase in CerS6 expression (p < 0.001). CerS2 shows a preference for 16 and 18 carbon chain lengths, consistent with specific increases in dihydroceramide and ceramide C16:0 and C18:0 in cortex of mice during acute ethanol withdrawal. Sphingomyelin hydrolase expression overall remained slightly decreased but trended towards normalization. ACER3 and ASAH1 normalized, but ACER2 increased (P < 0.001). Sphingomyelin synthases show a trend toward normalization. These expression patterns are consistent with our biochemical findings of normalization in most ceramide species with specific increases C16:0 and C18:0 ceramides, and general decreases in sphingomyelins during acute withdrawal.

Discussion

The biochemical effects of binge EtOH consumption on neural tissues are complex and involve the combined effects of repeated intoxication followed by withdrawal. In the current study we used a lipidomic approach to determine if binge EtOH consumption modified ceramide metabolism in cortex. During EtOH intoxication, cortical levels of multiple ceramides and glucoceramides were decreased. These lipidomics findings in combination with the gene expression data suggest that ceramide may be converted into sphingomyelin (by increased expression of sphingomyelin synthase; SMS1 and SMS2) and/or sphingosine/sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) (by increased expression of acid ceramidase; ASAH1)(Figure 7). This pattern of ceramide metabolism suggests that EtOH intoxication produces a neuroprotective shift in ceramide metabolism. There is considerable evidence that inhibition of ceramide production, and increases in S1P are protective in a variety of model systems (Culmsee et al. 2002, Yung et al. 2012, Yu et al. 2000, Haughey et al. 2004), and a previous report of EtOH exposure in young mice found that S1P was transiently increased 2-3 h following EtOH exposure, followed by increased caspase 3 activation that peaked at 8 h following exposure (Chakraborty et al. 2012). These data suggest that a shift in ceramide metabolism toward SIP may protect the CNS during EtOH intoxication. These data also suggest that neural damage associated with binge drinking may be associated with the increased ceramide production during the withdrawal period following intoxication.

Figure 7. Binge EtOH associated regulation of ceramide metabolism.

Primary metabolic pathways regulated during EtOH intoxication are depicted in green and those most active during withdrawal are depicted in red.

In episodic binge drinkers withdrawal symptoms are frequently mild and do reach the threshold for a clinical definition of EtOH withdrawal. Nevertheless, there are dramatic biological effects during this acute withdrawal period that may make the brain vulnerable to damage. Many of the observed neuroadaptive changes associated with binge EtOH intake occur during the acute withdrawal period, beginning within hours after the last intake of EtOH. Alcohol withdrawal has been associated with functional disconnections of the medial prefrontal cortex and the central nucleus of the amygdala in a rat model of bine EtOH intake. These alterations in neural networks are associated with recruitment of GABA and corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex, and impaired executive control over motivated behavior (George et al. 2012). Although the molecular mechanisms for these neuroadaptive changes are currently unknown, our data suggest that stress-induced alterations in ceramide metabolism could contribute to neural remodeling. Ceramide plays important regulatory roles in neural function through biophysical effects on membrane microdomains, and through protein-lipid interactions that regulate a wide variety of trophic and toxic signaling (Wheeler et al. 2009, Simons & Ikonen 1997, Furukawa & Mattson 1998, Furuya et al. 1998, Inokuchi et al. 1998, Ping & Barrett 1998, Brann et al. 1999, Coogan et al. 1999, Yang 2000, Fasano et al. 2003, Ito & Horigome 1995). Oxidative and inflammatory stressors induced during acute EtOH withdrawal in both chronic and binge conditions (Elibol-Can et al. 2011, Collins & Neafsey 2012), and are known to be potent modulators of enzymes that regulate ceramide formation through the catabolism of sphingomyelin to ceramide by the actions of sphingomylinases (Hannun 1996, Haughey et al. 2008, Nikolova-Karakashian & Rozenova 2010).

During acute withdrawal we observed selective increases in dihydroceramides (precursors to ceramide) and the associated mature ceramide species (as defined by acyl chain length). This pattern of ceramide production suggests that de novo and/or salvage ceramide synthesis was evoked during the acute withdrawal state. In humans and rodents there are at least six ceramide synthase (CerS) family members that each use a relatively restricted subset of fatty acid CoAs for N-acylation of the sphingoid long-chain base as follows: CerS1 (C18), CerS2 (C22, C24, C26), CerS3 (C18, C24), CerS4 (C18, C20), CerS5 (C14, C16), CerS6 (C14, C16) (see (Grosch et al. 2012)for a review). Increased ceramide levels during acute withdrawal in the mouse model of binge drinking appeared to be driven largely through increased expression of CerS2 and CerS4. Although gene expression of enzymes does not always correlate with activity, we found striking associations between the expression of these ceramide synthases and the their metabolic products. EtOH withdrawal resulted in selective increase of C16:0, C18:0 and C20:0 ceramide that were consistent with increases in CerS4 and CerS6 expression. Although very little is known about the regulation of CerS4 expression and activity, CerS6 expression is known to be regulated by oxidative mechanisms. Oxidative stress induces expression of the CerS6 gene with specific accumulations of ceramide C16 in rat pancreatic INS-1E cells (Epstein et al. 2012). Likewise, oxidized phospholipids (1-palmitoyl-2-glutaroyl-snglycero-3-phosphocholine, and 1-palmitoyl-2-oxovaleroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) also have been demonstrated to increase CerS activity (Halasiddappa et al. 2013). In addition to oxidative stressors, the metabolism of EtOH may itself increase CerS6 expression. Activity of the EtOH metabolizing aldehyde dehydrogenase family member L1 (Aldh1L1) has been demonstrated to increase CerS6 expression through a p53-dependent mechanism (Hoeferlin et al. 2013). Thus, increases of ceramide C16:0, C18:0 and C20:0 during acute EtOH withdrawal may involve interactions between EtOH metabolism and oxidative reactions.

Acute withdrawal following binge intake of EtOH was also associated with decreased CerS2 expression, and corresponding decreases in dihydroceramide C22:0 and C24:0, consistent with the fatty acid preference of this enzyme. There were no apparent decreases in the corresponding mature ceramide species within the time frame of this study, possibly due to the longer turn over rates of ceramides that have been estimated to be 6.5 h to 3 days depending on the type of cells (Tettamanti 2004). Tissue culture studies have shown that molecular downregulation of CerS2 decreases very long-chain ceramides C22:0 and C24:0, but also results in a compensatory increase in the expression of CerS4, and CerS6 (in addition to CerS5), with associated increases in ceramides C16:0, C18:0 and C20:0 (Mullen et al. 2011). These results are strikingly similar to our observations of gene and ceramide profiles during acute EtOH withdrawal and suggest that a reduction in CerS2 expression may contribute to the increased expression of CerS4 and CerS6. Although our in vivo studies do not identify the neural cell types affected by EtOH, there is considerable evidence astrogllia may be particularly vulnerable to the toxic effects of EtOH through ceramide pathways induced by stress signaling and regulated by acid and neutral sphingomyelinase (Pascual et al. 2003, Schatter et al. 2005, De Vito et al. 2000). Neurons are also vulnerable to the toxic effects of EtOH by mechanisms that appear to involve de novo ceramide formation. (Saito et al. 2005). Together these data suggest that alcohol withdrawal may induce inflammatory and stress pathways that promote the catabolic formation of ceramide in astrocytes, while de novo ceramide production may be the preferred metabolic pathway for ceramide production in neurons during withdrawal.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. Our data on alcohol consumption was based on drinking behavior and known elimination rates in the mouse (Pastino et al. 1996). We did not directly measure blood alcohol. Therefore, we could not quantify the level of intoxication following alcohol exposure. The number of mice in each group (n=5) is relatively small. Thus, we may have underestimated the effects of EtOH on some ceramide and SM species that showed group trends, but did not quite reach significance.

Our data demonstrate that binge EtOH intoxication and acute withdrawal each produced distinct modifications in cortical ceramide metabolism. In particular, reductions in ceramides during EtOH intoxication were consistent with a neuroprotective phenotype, while increases of ceramide and decreases in sphingomyelin during withdrawal were consistent with a neurotoxic phenotype. These data suggest that neurobiological membranes may be sensitive to the effects of EtOH, and could be key regulators of neuroadaptive changes associated binge EtOH exposure. Future studies with larger sample sizes and additional time points following the last intake of alcohol would help further define the roles for ceramide metabolism in neurological damage associated with binge drinking.

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported by NIH grants MH077542, AG034849, AA0017408 and MH075673 to NJH.

Abbreviations

- CerS

ceramid synthase

- EtOH

ethanol

- S1P

sphingosine-1P

- SGMS

sphingomyelin synthase

- SMase

Sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase

- SphK

sphingosine kinase

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Bandaru VV, McArthur JC, Sacktor N, Cutler RG, Knapp EL, Mattson MP, Haughey NJ. Associative and predictive biomarkers of dementia in HIV-1-infected patients. Neurology. 2007;68:1481–1487. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260610.79853.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brann AB, Scott R, Neuberger Y, Abulafia D, Boldin S, Fainzilber M, Futerman AH. Ceramide signaling downstream of the p75 neurotrophin receptor mediates the effects of nerve growth factor on outgrowth of cultured hippocampal neurons. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1999;19:8199–8206. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08199.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty G, Saito M, Shah R, Mao RF, Vadasz C, Saito M. Ethanol triggers sphingosine 1-phosphate elevation along with neuroapoptosis in the developing mouse brain. Journal of neurochemistry. 2012;121:806–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07723.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins MA, Neafsey EJ. Ethanol and adult CNS neurodamage: oxidative stress, but possibly not excitotoxicity. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2012;4:1358–1367. doi: 10.2741/465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins MA, Zou JY, Neafsey EJ. Brain damage due to episodic alcohol exposure in vivo and in vitro: furosemide neuroprotection implicates edema-based mechanism. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 1998;12:221–230. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coogan AN, O'Neill LA, O'Connor JJ. The P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor SB203580 antagonizes the inhibitory effects of interleukin-1beta on long-term potentiation in the rat dentate gyrus in vitro. Neuroscience. 1999;93:57–69. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corso TD, Mostafa HM, Collins MA, Neafsey EJ. Brain neuronal degeneration caused by episodic alcohol intoxication in rats: effects of nimodipine, 6,7-dinitro-quinoxaline-2,3-dione, and MK-801. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 1998;22:217–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Collins MA, Dlugos C, et al. Alcohol-induced neurodegeneration: when, where and why? Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2004;28:350–364. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000113416.65546.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culmsee C, Gerling N, Lehmann M, Nikolova-Karakashian M, Prehn JH, Mattson MP, Krieglstein J. Nerve growth factor survival signaling in cultured hippocampal neurons is mediated through TrkA and requires the common neurotrophin receptor P75. Neuroscience. 2002;115:1089–1108. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00539-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vito WJ, Xhaja K, Stone S. Prenatal alcohol exposure increases TNFalpha-induced cytotoxicity in primary astrocytes. Alcohol. 2000;21:63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(00)00078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elibol-Can B, Jakubowska-Dogru E, Severcan M, Severcan F. The effects of short-term chronic ethanol intoxication and ethanol withdrawal on the molecular composition of the rat hippocampus by FT-IR spectroscopy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:2050–2062. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein S, Kirkpatrick CL, Castillon GA, Muniz M, Riezman I, David FP, Wollheim CB, Riezman H. Activation of the unfolded protein response pathway causes ceramide accumulation in yeast and INS-1E insulinoma cells. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:412–420. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M022186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasano C, Miolan JP, Niel JP. Modulation by C2 ceramide of the nicotinic transmission within the coeliac ganglion in the rabbit. Neuroscience. 2003;116:753–759. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00760-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K, Mattson MP. The transcription factor NF-kappaB mediates increases in calcium currents and decreases in NMDA- and AMPA/kainate-induced currents induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha in hippocampal neurons. J Neurochem. 1998;70:1876–1886. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70051876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuya S, Mitoma J, Makino A, Hirabayashi Y. Ceramide and its interconvertible metabolite sphingosine function as indispensable lipid factors involved in survival and dendritic differentiation of cerebellar Purkinje cells. Journal of neurochemistry. 1998;71:366–377. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71010366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George O, Sanders C, Freiling J, Grigoryan E, Vu S, Allen CD, Crawford E, Mandyam CD, Koob GF. Recruitment of medial prefrontal cortex neurons during alcohol withdrawal predicts cognitive impairment and excessive alcohol drinking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18156–18161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116523109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosch S, Schiffmann S, Geisslinger G. Chain length-specific properties of ceramides. Prog Lipid Res. 2012;51:50–62. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halasiddappa LM, Koefeler H, Futerman AH, Hermetter A. Oxidized phospholipids induce ceramide accumulation in RAW 264.7 macrophages: role of ceramide synthases. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannun YA. Functions of ceramide in coordinating cellular responses to stress. Science. 1996;274:1855–1859. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haughey NJ, Cutler RG, Tamara A, McArthur JC, Vargas DL, Pardo CA, Turchan J, Nath A, Mattson MP. Perturbation of sphingolipid metabolism and ceramide production in HIV-dementia. Annals of neurology. 2004;55:257–267. doi: 10.1002/ana.10828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haughey NJ, Steiner J, Nath A, McArthur JC, Sacktor N, Pardo C, Bandaru VV. Converging roles for sphingolipids and cell stress in the progression of neuro-AIDS. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library. 2008;13:5120–5130. doi: 10.2741/3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeferlin LA, Fekry B, Ogretmen B, Krupenko SA, Krupenko NI. Folate stress induces apoptosis via p53-dependent de novo ceramide synthesis and up-regulation of ceramide synthase 6. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:12880–12890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.461798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt WA. Are binge drinkers more at risk of developing brain damage? Alcohol. 1993;10:559–561. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(93)90083-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inokuchi J, Mizutani A, Jimbo M, et al. A synthetic ceramide analog (L-PDMP) up-regulates neuronal function. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1998;845:219–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito A, Horigome K. Ceramide prevents neuronal programmed cell death induced by nerve growth factor deprivation. Journal of neurochemistry. 1995;65:463–466. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65010463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobus J, Tapert SF. Neurotoxic effects of alcohol in adolescence. Annual review of clinical psychology. 2013;9:703–721. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen TD, Spassieva S, Jenkins RW, Kitatani K, Bielawski J, Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Selective knockdown of ceramide synthases reveals complex interregulation of sphingolipid metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:68–77. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M009142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Oehring EM, Jung YC, Sullivan EV, Hawkes WC, Pfefferbaum A, Schulte T. Midbrain-driven Emotion and Reward Processing in Alcoholism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013 doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolova-Karakashian MN, Rozenova KA. Ceramide in stress response. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;688:86–108. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6741-1_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obernier JA, White AM, Swartzwelder HS, Crews FT. Cognitive deficits and CNS damage after a 4-day binge ethanol exposure in rats. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2002;72:521–532. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00715-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual M, Valles SL, Renau-Piqueras J, Guerri C. Ceramide pathways modulate ethanol-induced cell death in astrocytes. Journal of neurochemistry. 2003;87:1535–1545. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastino GM, Sultatos LG, Flynn EJ. Development and application of a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for ethanol in the mouse. Alcohol and alcoholism. 1996;31:365–374. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a008163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A, Desmond JE, Galloway C, Menon V, Glover GH, Sullivan EV. Reorganization of frontal systems used by alcoholics for spatial working memory: an fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2001;14:7–20. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ping SE, Barrett GL. Ceramide can induce cell death in sensory neurons, whereas ceramide analogues and sphingosine promote survival. Journal of neuroscience research. 1998;54:206–213. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19981015)54:2<206::AID-JNR8>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JS, Best K, Belknap JK, Finn DA, Crabbe JC. Evaluation of a simple model of ethanol drinking to intoxication in C57BL/6J mice. Physiology & behavior. 2005;84:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Chakraborty G, Hegde M, Ohsie J, Paik SM, Vadasz C. Involvement of ceramide in ethanol-induced apoptotic neurodegeneration in the neonatal mouse brain. Journal of neurochemistry. 2010;115:168–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06913.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Chakraborty G, Mao RF, Wang R, Cooper TB, Vadasz C. Ethanol alters lipid profiles and phosphorylation status of AMP-activated protein kinase in the neonatal mouse brain. Journal of neurochemistry. 2007;103:1208–1218. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Cooper TB, Vadasz C. Ethanol-induced changes in the content of triglycerides, ceramides, and glucosylceramides in cultured neurons. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2005;29:1374–1383. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000175011.22307.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatter B, Jin S, Loffelholz K, Klein J. Cross-talk between phosphatidic acid and ceramide during ethanol-induced apoptosis in astrocytes. BMC Pharmacol. 2005;5:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons K, Ikonen E. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature. 1997;387:569–572. doi: 10.1038/42408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Deshmukh A, De Rosa E, Rosenbloom MJ, Pfefferbaum A. Striatal and forebrain nuclei volumes: contribution to motor function and working memory deficits in alcoholism. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:768–776. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tettamanti G. Ganglioside/glycosphingolipid turnover: new concepts. Glycoconj J. 2004;20:301–317. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000033627.02765.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993-2001. J Am Coll Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler D, Knapp E, Bandaru VV, Wang Y, Knorr D, Poirier C, Mattson MP, Geiger JD, Haughey NJ. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced neutral sphingomyelinase-2 modulates synaptic plasticity by controlling the membrane insertion of NMDA receptors. J Neurochem. 2009;109:1237–1249. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SN. Ceramide-induced sustained depression of synaptic currents mediated by ionotropic glutamate receptors in the hippocampus: an essential role of postsynaptic protein phosphatases. Neuroscience. 2000;96:253–258. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00582-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu ZF, Nikolova-Karakashian M, Zhou D, Cheng G, Schuchman EH, Mattson MP. Pivotal role for acidic sphingomyelinase in cerebral ischemia-induced ceramide and cytokine production, and neuronal apoptosis. J Mol Neurosci. 2000;15:85–97. doi: 10.1385/JMN:15:2:85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung LM, Wei Y, Qin T, Wang Y, Smith CD, Waeber C. Sphingosine kinase 2 mediates cerebral preconditioning and protects the mouse brain against ischemic injury. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2012;43:199–204. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.626911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahr NM, Mayer D, Rohlfing T, et al. Brain injury and recovery following binge ethanol: evidence from in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:846–854. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahr NM, Mayer D, Rohlfing T, Orduna J, Luong R, Sullivan EV, Pfefferbaum A. A mechanism of rapidly reversible cerebral ventricular enlargement independent of tissue atrophy. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1121–1129. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou JY, Martinez DB, Neafsey EJ, Collins MA. Binge ethanol-induced brain damage in rats: effect of inhibitors of nitric oxide synthase. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 1996;20:1406–1411. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]