Abstract

In a recent report, our group presented clinical research data supporting the role of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) deficiency in susceptibility to meningococcal disease (W. A. Bax, O. J. J. Cluysenaer, A. K. M. Bartelink, P. C. Aerts, R. A. B. Ezekowitz, and H. van Dijk, Lancet 354:1094-1095, 1999). This association was reported earlier by Hibberd et al. (M. L. Hibberd, M. Sumiya, J. A. Summerfield, R. Booy, M. Levin, and the Meningococcal Research Group, Lancet 353:1049-1053, 1999) but was not based on family data. Our study included three members of one family who had acquired meningococcal meningitis in early adulthood. The objective of the present study was to investigate whether the genotypes of the MBL gene in this family, analyzed by PCR, correlate with MBL concentrations. We found that genotype variants in the MBL gene and promoter region match the low functional MBL levels (<0.25 μg of equivalents/ml) in the sera of the three patients in this family and that a significant correlation between genotype MBL deficiency and meningococcal disease existed.

Three point mutations in the mannose-binding lectin (MBL) gene are each known to reduce serum lectin levels and contribute to a deficiency of the MBL protein. In 1995, Madsen et al. (8) showed that additional mutations in the promoter region of the MBL gene play an additional role in reduced MBL levels. That paper reported the frequencies of the promoter haplotypes which regulate the expression of the peptide in populations of pure Eskimos, Caucasians, and black Africans and discussed their putative role.

This short report presents the genotypic data (gene and promoter variants) from a large family with three members who had acquired meningococcal meningitis in early childhood and the correlation between these genotypes and MBL concentrations in the sera (described in a recent report [1]).

EDTA blood samples were collected from all known members of the family, followed by genomic DNA isolation using a commercially available isolation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit; QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Genomic PCRs were performed in 50-μl volumes containing primers specific for the alleles described by Madsen et al. (8) in the exon 1 region (wild-type A and the variant alleles B, C, and D). The same was done for the variant alleles in the promoter region of the MBL gene: H and L, X and Y. DNA was amplified as described by Madsen et al. (7, 8), using general PCR and site-directed mutagenesis PCR for types A, B, C, and D and PCR with sequence-specific priming for types H/L and X/Y. Wild-type (type A) and B, C, and D alleles were distinguished by restriction enzyme digestions of the PCR products (7, 8). The cis/trans locations of the promoter variants H/L and X/Y relative to the structural variants A, B, C, and D were determined as well. Madsen and colleagues stressed in their report (8) that all of their attempts to use the PCR with sequence-specific priming technique in typing the H allele had failed. We, in contrast, succeeded by using the primer 5′-TTA-CCC-AGG-CAA-GCC-TGT-G-3′ and 40 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 60 s at 68°C, and 60 s at 72°C (see Fig. 1).

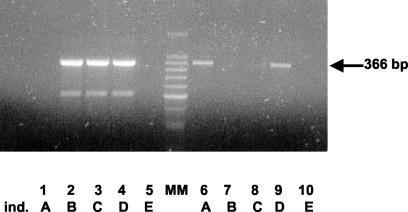

FIG. 1.

PCR to discriminate between the H and L alleles in the promoter region of the MBL gene. Lanes 1 to 5, PCR for the L allele; lanes 6 to 10, PCR for the H allele. Samples shown are from an individual (ind.) who expressed both the L and H alleles (D, lanes 4 and 9) and from individuals who expressed only the L allele (B, lanes 2 and 7; C, lanes 3 and 8) or only the H allele (A, lanes 1 and 6). Lanes 5 and 10 are negative controls. MM, size marker DNA.

MBL concentrations in serum samples of the family members were measured using a functional MBL assay (6) with purified wild-type MBL as a reference protein (a kind gift from P. Garred, Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark) as previously described (1).

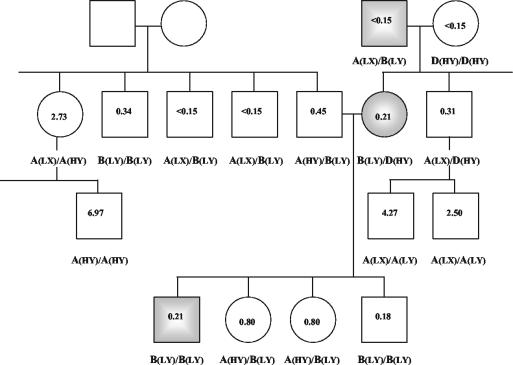

Three variants of polymorphism in the coding region of the MBL gene were found (A [wild type], B, and D), which led to the combinations A/A, A/B, A/D, B/D, B/B, and D/D. This family study confirms the pattern predicted by Madsen et al. (8) in their model of the evolution of the MBL gene: the X allele was found only in combination with the A variant and the L allele, while the D variant was exclusively found in combination with HY and the B variant was found only with LY (see Fig. 2). In addition, the HY, LY, and LX haplotypes correlated with different levels of serum MBL: HY with high, LY with intermediate, and LX with low levels. It is remarkable that variants in the promoter region (LX associated with wild-type A) correlate with relative low levels of functional MBL in heterozygotes for MBL codon variants.

FIG. 2.

Family pedigree of the three patients with meningitis (shaded boxes). Values correspond to MBL concentrations in serum expressed in microgram equivalents/milliliter. Genotypes A (wild type), B, C, and D in the coding region of MBL are shown, and the alleles in the promoter region are given in parentheses.

Results of clinical studies have shown associations between MBL mutations and susceptibility to infection in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (3), increased episodes of acute respiratory infection (5), and risk of invasive pneumococcal disease (10) and meningococcal disease (4). MBL deficiency is also associated with severe atherosclerosis (9) and risk of miscarriage (2).

In conclusion, earlier (Lancet) data (1) and our group's recent genotypic findings, mentioned here, indicate that MBL genotypes match their corresponding phenotypes, suggesting that MBL phenotyping (6) can be used to provisionally identify MBL-deficient subjects in a human population.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the “Stichting Bijstand” of the Meander Medical Centre, Amersfoort, The Netherlands.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bax, W. A., O. J. J. Cluysenaer, A. K. M. Bartelink, P. C. Aerts, R. A. B. Ezekowitz, and H. van Dijk. 1999. Association of familial deficiency of mannose-binding lectin and meningococcal disease. Lancet 354:1094-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christiansen, O. B., D. C. Kilpatrick, V. Souter, K. Varming, S. Thiel, and J. C. Jens. 1999. Scand. J. Immunol. 49:193-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garred, P., H. O. Madsen, B. Hoffmann, and A. Svejgaard. 1995. Increased frequency of homozygosity of abnormal mannan-binding-protein alleles in patients with suspected immunodeficiency. Lancet 346:941-943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hibberd, M. L., M. Sumiya, J. A. Summerfield, R. Booy, M. Levin, and the Meningococcal Research Group. 1999. Association of variants of the gene for mannose-binding lectin with susceptibility to meningococcal disease. Lancet 353:1049-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koch, A., M. Melbye, P. Sorensen, P. Homoe, H. O. Madsen, K. Molbak, C. H. Hansen, L. H. Andersen, G. Weinkauff Hahn, and P. Garred. 2001. Acute respiratory tract infections and mannose-binding lectin insufficiency during acute early childhood. JAMA 285:1316-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuipers, S., P. C. Aerts, A. G. Sjöholm, T. Harmsen, and H. van Dijk. 2002. A hemolytic assay for the estimation of functional mannose binding lectin (MBL) levels in human serum. J. Immunol. Methods 268:149-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madsen, H. O., P. Garred, J. A. L. Kurtzhals, L. U. Lamm, L. P. Ryder, S. Thiel, and A. Svejgaar. 1994. A new frequent allele is the missing link in the structural polymorphism of the human mannan-binding protein. Immunogenetics 40:37-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madsen, H. O., P. Garred, S. Thiel, J. A. L. Kurtzhals, L. U. Lamm, L. P. Ryder, and A. Svejgaard. 1995. Interplay between promoter and structural gene variants control basal serum level of mannan-binding protein. J. Immunol. 155:3013-3020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madsen, H. O., V. Videm, A. Svejgaard, J. L. Svennevig, and P. Garred. 1998. Association of mannose-binding lectin deficiency with severe atherosclerosis. Lancet 352:959-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roy S., K. Knox, S. Segal, D. Griffiths, C. E. Moore, K. I. Welsh, A. Smarason, N. P. Day, W. L. McPheat, D. W. Crook, A. V. S. Hill, and the Oxford Pneumococcal Surveillance Group. 2002. MBL genotype and risk of invasive pneumococcal disease: a case-control study. Lancet 359:1569-1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]