Abstract

To understand the role of environmental and genetic influences on nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) in populations at high risk of NPC, we have performed a case-control study in Guangxi Province of Southern China in 2004-2005. NPC cases (n=1049) were compared to 785 NPC-free matched controls who were seropositive for IgA antibodies (IgA) to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) capsid antigen (VCA)—a predictive marker for NPC in Chinese populations. A questionnaire was used to capture exposure and NPC family history data. Risk factors associated with NPC in a multivariant analysis model were the following: 1) a first, second or third degree relative with NPC [Attributable risk (AR)= 6%, Odds ratio (OR) = 3.1, 95%CI = 2.0-4.9, p < 0.001]; 2) consumption of salted fish 3 or more than 3 times per month (AR=3%, OR = 1.9, 95%CI = 1.1-3.5, p = 0.035); 3) exposure to domestic wood cooking fires for more than 10 years (AR=69%, OR = 5.8, 95%CI = 2.5-13.6, p < 0.001); and 4) exposure to occupational solvents for 10 or less years (AR=4%, OR = 2.6, 95%CI = 1.4-4.8, p = 0.002). Consumption of preserved meats or a history of tobacco smoking were not associated with NPC (P>0.05). We also assessed the contribution of EBV/IgA/VCA antibody serostatus to NPC risk—32.2% of NPC can be explained by IgA+ status. However, family history and environmental risk factors cumulatively explained only 2.7% of NPC development in NPC high risk population. These findings should have important public health implications for NPC risk reduction in endemic regions.

Keywords: Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma, Risk factor, Epidemiology, Southern China, Epstein Barr Virus

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is rare in most regions of the world; however it is a common cancer in Southern China, especially in persons of Cantonese origin. The incidence rate of NPC for males in the southern Chinese provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi is more than 20 per 100,000 person-years and up to 25-40 per 100,000 person-years in some areas bordering the Xijiang River and Pearl River drainages in these two provinces1, 2. In Southeast Asia, the incidence of NPC seems to vary by degree of racial and cultural Cantonese admixture 3. In Hong Kong, a region with a high immigrant Cantonese population, a recent 20 year longitudinal study has shown that the NPC incidence for males is more than 20 per 100,000 person-years 4. Intermediate incidence levels were observed in the Thai, Macaonese and Malay indigenous populations, who have a history of intermarriage with Cantonese. In northern China, such as Beijing and Tianjing, the incidence of NPC in males is less 2 per 100,000 person-years3. The incidence of NPC begins to increase after the age of 30; 93% of NPC patients are over 30 years old at diagnosis and the NPC incidence peaks at 45-55 years of age. NPC is the 8th leading cause of cancer death in China and, a leading cause of cancer death in the Guangdong and Guangxi population5, 6.

It has been well established that reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in the epithelial mucosal lining of the nasopharynx is strongly associated with NPC7. The presence of IgA antibodies to EBV capsid antigens (EBV/IgA/VCA) may be a biomarker for EBV reactivation and serves as a predictive marker for NPC in Chinese populations 8, 9. A 10-year longitudinal study in Guangxi province indicated that NPC incidence was 467, 2 and 28 per 100,000 people-years for EBV/IgA/VCA positive (IgA+), EBV/IgA/VCA negative (IgA-) participants, and the general population, respectively10. The same study showed that although 93% of NPC patients came from the 5% of the population that were IgA+ population, less than 5% of IgA+ individuals will ever develop NPC. Consequently, the population at highest risk of NPC is the IgA+ population in southern China. The incidence of NPC in the IgA− population in southern China is similar to the general population in northern China3.

Familial aggregation of NPC cases has been observed in both high and low risk populations in different geographic regions 11-13. The non-viral environmental exposures most consistently associated with NPC are traditional southern Chinese consumption of salted fish and other preserved meats containing volatile nitrosamine 14-19. While cigarette smoking is a known risk factor for cancers of various organ systems, previous studies on the association between smoking and NPC in NPC endemic areas have not been consistent. Several case control studies reported that heavy smoking increased NPC risk by 2- to 4- fold 20-24; however, other studies found no association 14, 25-27. Discrepant results were also reported for domestic wood cooking fire exposures and occupational exposures to solvents with some studies but not other reporting associations with NPC28-33.

Most previous epidemiological studies to identify non-viral environmental risk factors for NPC have not considered EBV/IgA/VCA serum status, although IgA+ status appears to confer the highest known risk of NPC. To systemically evaluate non-EBV environmental risk factors in the development of NPC in a high-risk population, we conducted a case-control study with 1049 NPC cases and 785 IgA+ controls in the Guangxi province of southern China. In this study, we examined familial recurrence, ethnicity, and environmental factors, including dietary, smoking, household, and occupational exposures in NPC cases and IgA+ controls to evaluate non-viral risk factors in NPC development in a high-risk population in southern China.

Materials and Methods

Cohort design

Subjects residing in the catchment area along the Xijiang River on the border of the Guangxi and Guangdong provinces of southern China were invited to enroll in the study from November, 2004 to October, 2005. Cases were incident or prevalent, biopsy-confirmed NPC cases (n=1049). The incident NPC were cases who were diagnosed with NPC during the enrollment period and referred to our study. The prevalent cases were the cases who were diagnosed as NPC between January 2001 to October 2004. In our cohort, 81.6% of cases were prevalent cases and 18.4% cases were incident cases. Treatment information was available for 95% cases. Of these, 99.4% received radiotherapy, 0.4% received chemotherapy, 5.2% received both radio- and chemotherapy and 0.2% rejected any therapy. Treatment plans were not affected by enrollment in this study. Controls (n=785) were EBV/IgA/VCA positive (IgA+), NPC free at the time of study enrollment and matched to NPC cases on age, sex, and district/township of residence. Controls were determined to be NPC free by physical examination of the nasopharyngeal cavity by oncologists using indirect naso-endoscope. NPC cases were hospitalized patients at Wuzhou Red Cross Hospital in Wuzhou City and outpatients at Cangwu Institute for NPC Control and Prevention in Cangwu County. Controls were identified from records of EBV/IgA/VCA screening that occurred during 2001 to 2003 and those who were EBV/IgA/VCA positive were asked to participate in the study. All participants self-identified as Han Chinese, self-reported 6 or more months of residency in Guangdong or Guangxi, and self-reported Guangdong or Guangxi Provincial ancestry for either maternal or paternal ancestry for at least 3 generations. Persons of minority ethnicity or who had blood relatives enrolled in the study were excluded. Institutional review board approval was obtained from all participating institutes, and informed consent was obtained from all study participants or their respective legal guardians.

Questionnaire

Trained local health workers administered a questionnaire to each participant at enrollment. The questionnaire captured family history of NPC, parental ancestry for three generations, age, sex, dietary and smoking habits, household exposures to wood fires, and occupational exposures to solvents. Responses were recorded by double-entry and verification of all data was performed to avoid data entry errors. Probands were asked if there was a family history of NPC in first (children, siblings or parents), second (aunts or uncles, nieces or nephews, and grandparents) or third degree relatives (first cousins). Information on salty fish and preserved meat captured frequency of consumption per month (≥3 times/month, < 3 times/month). Questions on cigarette smoking included current and past smoking habits and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Questions on household and occupational exposures captured data on domestic exposure to wood fires for cooking and occupational exposures to solvents (e.g., formaldehyde, acetone, toluene or xylene), and duration of exposure (>10 years or ≤ 10 years). The response rate for the questions on family history of NPC, salted fish, preserved meat, smoking, wood fire and solvent were 99.9%, 96.4%, 96%, 98.9%, 98.6 and 98.1.

Laboratory and clinical data

Date of NPC diagnoses, clinical stage at presentation, tumor histological results, therapeutic treatment (radiation, and/or chemotherapy) and response to treatment were obtained from NPC cases clinical records. Serological testing for IgA antibodies to EBV capsid antigens (EBV/IgA/VCA) and IgA antibodies to EBV early antigen (EBV/IgA /EA) was performed on a serum sampled from peripheral blood samples obtained by venipuncture at study enrollment. All serological testing was done by immunoenzymatic assay at the Wuzhou Red Cross Hospital, Wuzhou City. B95-8 cells were used for the detection of VCA-IgA antibodies, and Raji cells were used for EA-IgA test. Sera at 1:10 to 1:640 (1:5 to 1:160 for EA-IgA) dilutions were added to cells in separate wells and the slides were incubated at 37°C for 30 min at a humid atmosphere and washed 3 times with PBS. Horseradish peroxidase labeled antihuman IgA antibody at the appropriate dilution was added to the slides and the slides were further incubated at 37°C for 30 min, washed 3 times with PBS and immersed into diaminobenzene solution with H2O2 for 10 min. Positive and negative controls were included in each experiment34. The cut-off value is 1:10 and 1:5 for IgA/VCA and IgA/EA, respectively.

Biological blood sample collection

Peripheral blood samples were collected from all cases and controls, processed and stored as described previously 35.

Statistical analysis

EBV/IgA/EA antibody presence and EBV/IgA/VCA titer were compared using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The association of individual risk factors with NPC was analyzed using multiple logistic regression, with the reference group being individuals with no reported exposure. A corresponding multivariate analysis, including measures for all risk factors, was also explored. For each explanatory variable, we conditioned the multivariate analysis on NPC family history, dietary salted fish, dietary preserved meat, smoking, domestic exposure to wood fire and occupational exposure to solvents. Reported measures of association are odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p values. Due to small sample sizes in some of the risk groups, bootstrapped confidence interval estimates, using 10,000 repetitions, are reported for odds ratios comparing the joint effects of risk factors. The attributable risk (AR) and explained fraction (EF) were calculated using the method described by Nelson and O’Brien.36 We used the IgA+ proportion (5%) in the general population from a 10-year follow-up study to estimate prevalence in the general population and to calculate AR and EF 10. Because our disease is rare we can substitute the Odds Ratio (OR) for the Relative Risk (RR) when calculating the AR for NPC family history, salty fish, exposure to wood fire and solvent. The formula is as follows: AR = prevalence of exposure in NPC * (OR - 1) / OR. EBV/IgA/VCA antibody negative NPC cases (n=39) were not included in the analysis in the Tables 2, 3, and 4. All statistical analyses were carried out using R version 2.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) or SAS 9.1 software.

Table 2.

Odds ratios for the association of NPC family history, dietary salt fish, preserved meat, smoking, wood fire and solvent to risk of NPC

| Cases (%) | Controls (%) | Simple Model |

Multivariant Model§ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPC with IgA+ | IgA+ | OR | 95%CI | p-value | OR | 95%CI | p-value | AR* ( %) | EF** (%) | |

| Relative with NPC | ||||||||||

| 1st degree | 75 (7.4) | 23 (2.9) | 2.65 | 1.64-4.27 | < 0.001 | 2.81 | 1.69-4.67 | < 0.001 | 5 | |

| 1st, 2nd & 3rd degree | 100 (9.9) | 29 (3.7) | 2.86 | 1.87-4.37 | < 0.001 | 3.09 | 1.97-4.86 | < 0.001 | 6 | 0.6 |

| Salty fish | 0.5 | |||||||||

| Never | 633 (65.1) | 573 (75.6) | ||||||||

| < 3 times/month | 274 (28.2) | 156 (20.6) | 1.59 | 1.27-1.99 | < 0.001 | 1.23 | 0.83-1.81 | 0.304 | ||

| ≥ 3 times/month | 65 (6.7) | 29 (3.8) | 2.03 | 1.29-3.19 | 0.002 | 1.9 | 1.05-3.47 | 0.035 | 3 | |

| Preserved meat | ||||||||||

| Never | 691 (71.2) | 612 (81.2) | ||||||||

| < 3 times/month | 238 (24.5) | 119 (15.8) | 1.77 | 1.39-2.26 | < 0.001 | 1.29 | 0.84-1.96 | 0.24 | ||

| ≥ 3 times/month | 41 (4.2) | 23 (3.1) | 1.58 | 0.94-2.66 | 0.086 | 1.03 | 0.51-2.05 | 0.94 | ||

| Smoking | ||||||||||

| Never | 488 (48.3) | 384 (49.2) | ||||||||

| Smoker | 522 (51.7) | 396 (50.8) | 1.04 | 0.86-1.25 | 0.701 | 0.92 | 0.76-1.12 | 0.405 | ||

| < 10 cig. ‡/day | 33 (3.3) | 32 (4.1) | 0.81 | 0.49-1.34 | 0.417 | 0.7 | 0.41-1.19 | 0.186 | ||

| 10-20 cig./day | 385 (38.5) | 307 (39.6) | 0.99 | 0.81-1.21 | 0.897 | 0.89 | 0.72-1.10 | 0.272 | ||

| > 20 cig./day | 94 (9.4) | 53 (6.8) | 1.4 | 0.97-2.01 | 0.071 | 1.23 | 0.84-1.81 | 0.286 | ||

| Wood fire | 0.9 | |||||||||

| Never | 9 (0.9) | 23 (2.9) | ||||||||

| Exposure | 999 (99.1) | 761 (97.1) | 3.35 | 1.54-7.30 | 0.002 | 5.04 | 2.18-11.65 | < 0.001 | 70 | |

| ≤ 10 years | 22 (2.2) | 56 (7.2) | 1 | 0.40-2.51 | 0.993 | 1.3 | 0.49-3.46 | 0.601 | ||

| > 10 years | 963 (96.9) | 697 (89.8) | 3.53 | 1.62-7.68 | 0.001 | 5.82 | 2.50-13.57 | < 0.001 | 69 | |

| Solvent | 0.7 | |||||||||

| Never | 914 (91.7) | 739 (96.1) | ||||||||

| Exposure | 83 (8.3) | 30 (3.9) | 2.24 | 1.46-3.44 | <0.001 | 2.17 | 1.32-3.58 | 0.002 | 5 | |

| ≤ 10 years | 62 (6.2) | 17 (2.2) | 2.95 | 1.71-5.09 | < 0.001 | 2.61 | 1.43-4.78 | 0.002 | 4 | |

| > 10 years | 20 (2.0) | 8 (1.0) | 2.02 | 0.88-4.62 | 0.095 | 1.56 | 0.66-3.70 | 0.315 | ||

| Sum of factor EFs | 2.7 | |||||||||

Adjusting for all environmental exposures;

Attributable risk;

Explained fraction;

Cigarettes

Table 3.

Joint effects of NPC family history, dietary salty fish, wood fire and solvent exposure with the risk of NPC

| Risk factors | No. Cases | No. Controls | OR | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 3 | 12 | 0.22 | 0-0.67 |

| Solvent | 1 | 3 | 0.29 | 0-1 nf† |

| Wood fire‡ | 750 | 659 | 1.0 | |

| NPC family history | 5 | 3 | 1.46 | 0.29-Inf |

| Salty fish/Wood fire | 47 | 25 | 1.65 | 1.02-2.82 |

| Wood fire/Solvent | 56 | 21 | 2.34 | 1.44-4.22 |

| Family/Wood fire | 73 | 25 | 2.57 | 1.66-4.33 |

Infinity;

Wood fire was used as a reference

Table 4.

The association of having no or 2 or more risk factors^ with NPC

| No. of risk factors | No. Cases | No. Controls | OR | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | 12 | 0.22 | 0-0.65 |

| 1* | 756 | 665 | 1.0 | |

| ≥2 | 205 | 73 | 2.47 | 1.87-3.38 |

NPC family history, dietary salty fish, domestic wood fire or occupational solvent exposures;

Having 1 risk factor was used as a reference group.

Results

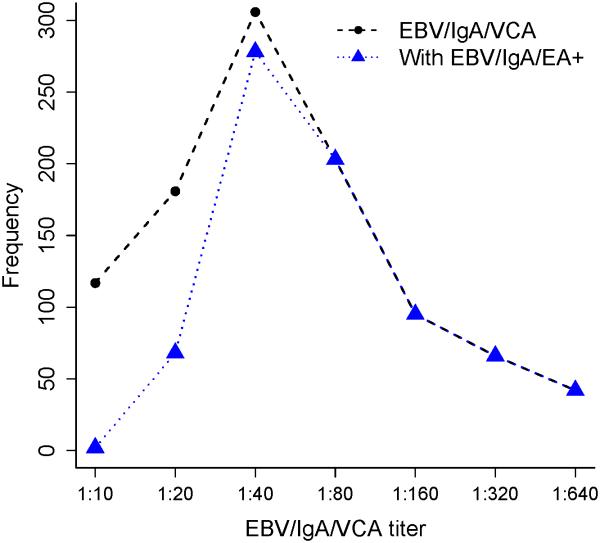

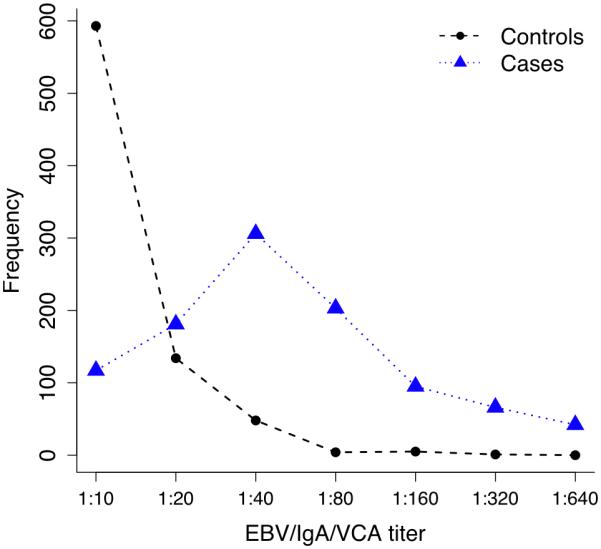

The mean age of 1049 cases at NPC diagnosis was 45±11 (range: 8-77) years and of 785 IgA+ controls at enrollment was 47±12 (range: 20-84) years (p>0.05); the male to female ratio was 2.6 for both cases and controls. The majority of the NPC cases (n=1010, 96.3%) were positive for EBV/IgA/VCA antibodies and EBV/IgA/EA (n=752, 72%). The mean titers for the NPC cases were 1:92 and 1:23 for EBV/IgA/VCA and EBV/IgA/EA antibodies, respectively. There was a strong positive correlation between the presence of EBV/IgA/EA antibodies and titer of IgA/VCA antibodies (r2 = 0.81, p <0.0001) (See Fig.1). The mean EBV/IgA/VCA titer was lower in IgA+ controls (1:15) compared to titers in NPC cases (p <0.0001). Figure 2 presents the EBV/IgA/VCA titer in NPC cases and IgA+ controls. Only 5% of EBV/IgA/VCA positive control subjects were EBV/IgA/EA positive.

Figure 1.

EBV/IgA/VCA antibody titer distribution and correlation with EBV/IgA/EA antibody positive status for NPC patients.

Figure 2.

EBV/IgA/VCA antibody titer distribution in NPC cases and IgA+ controls.

Tumor histological types were available for 1038 out of 1049 NPC cases (99%). Using the World Health Organization (WHO) classification for NPC (1991) criteria37, 14.9% of NPC patients had keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (KSCC) and 85.1% NPC cases had non-keratinizing carcinoma (NKC). Among the 39 EBV/IgA/VCA negative NPC cases, 28.2% had KSCC and 71.8% had NKC. The clinical stage at diagnosis was available for 1043 (99.4%) cases, 38.9% of whom were in early stage (stage I and II) and 61.1% were late stage (stage III and IV) at presentation. Among EBV/IgA/VCA negative NPC cases, 53.8% were early stage and 46.2% were late stage at presentation. For those with keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma, 50.3% were early stage and 49.7% were late stage. EBV/IgA/VCA negative patients have a higher rate of keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (p = 0.02) and lower rate of diagnosis at late stage (p = 0.055). Patients with non-keratinizing carcinoma had a higher rate of late stage NPC at diagnosis (p = 0.002).

Risk associated with a family history of NPC

Table 1 lists the characteristics of NPC cases who had first-, second- or third-degree relatives with a history of NPC (familial NPC), and NPC cases who reported having no NPC-affected relatives (non-familial NPC). There were no significant differences between familial NPC and non-familial NPC on gender, age of onset, histological types, clinical stage, EBV/IgA/VCA and EBV/IgA/EA antibody status. Among NPC cases, 104 of 1049 cases (9.9%) reported having a first-, second- or third-degree blood relative with NPC. More NPC cases (9.9%) than controls (3.7%) reported having one or more first, second or third degree relatives with NPC. Comparing NPC cases with IgA+ and IgA+ controls, we found individuals with a first, second or third-degree relative with NPC were 3-fold more likely to develop NPC (p < 0.001), after adjusting for all other risk factors, i.e., salted fish, preserved meat, smoking, wood fire and solvents (see below).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics for familial and nonfamilial NPC cases.

| Familial NPC ( n=104) |

Nonfamilial NPC ( n=945) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M/F ratio | 3.3:1 (80/24) | 2.5:1 (674/271) | 0.25 |

| Age† | 43.7 ± 11.3 | 45.2 ± 10.8 | 0.18 |

| EBV/IgA/VCA* | 96.2% | 96.3% | 0.79 |

| EBV/IgA/EA** | 77.9% | 71.2% | 0.17 |

| Histology | 0.46 | ||

| KSCC§ | 11.8% | 15.3% | |

| NKC§§ | 88.2% | 84.7% | |

| Stage | 0.53 | ||

| Early | 35.60% | 39.3% | |

| Late | 64.40% | 60.7% |

Mean ± SD;

IgA antibody to EBV viral capsid antigen, titer ≥ 1:10;

IgA antibody to EBV early antigen, titer ≥ 1:5;

Keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma;

Non-keratinizing carcinoma.

Risk associated with environmental factors

Table 2 lists the information and distribution of NPC family history, salty fish and preserved meat consumption, smoking habits, and wood fire and solvent exposures in NPC cases and IgA+ controls, plus the association between these factors and NPC risk in simple and multivariant models, adjusted for all environmental exposures. In a simple analysis, consumption of salty fish and preserved meats, domestic exposure to wood cooking fires, and occupational exposure to solvents were NPC risk factors (OR=1.58-3.53; p ≤ 0.002). After adjusting for all risk factors in a multivariant analysis, only consuming salty fish 3 or more than 3 times per month at the time of the interview (OR=1.9, 95% CI= 1.1-3.5), exposure to wood cooking fires for more than 10 years (OR=5.8, 95% CI =2.5-13.6), and exposure to solvents for 10 or less 10 years (OR=2.6, 95% CI=1.4-4.8) remained significant NPC risk factors. The exposure rates in cases and controls for occupational solvents, salty fish, and domestic exposures to wood cooking fires were 6%, 30%, and 98%, respectively. Half of cases (51.7%) and controls (50.8%) reported a history of smoking, but there were no significant associations between smoking and NPC.

To investigate the possible joint effects of family history of NPC, salty fish, wood fire and solvent exposure, we examined the association between one or two of these risk factors and NPC. Because the most frequent risk exposure was to wood cooking fires, we used wood fire exposure as the referent group in the analysis. Table 3 presents the results of single and pairwise combinations of exposure factors and family history on NPC risk. Individuals with no exposures to these risk factors were significantly less likely to develop NPC (OR=0.2, 95%CI=0-0.7). On the other hand, individuals reporting any 2 combination of risk factors were at greater risk (OR=1.5-2.6). We also analyzed the risk for individuals having none or having ≥ 2 risk factors compared to the reference group who have only 1 risk factor (Table 4). Consistent with the results presented in Table 3, there was increasing NPC risk for individuals with multiple environmental risk factors (OR=2.47, 95%CI=1.87-3.38).

To measure the impact of multiple environmental factors on nasopharyngeal carcinoma, the attributable risk (AR) was determined. The attributable risk for NPC to occupational exposure to solvents, NPC family history, salty fish consumption, and domestic exposure to wood cooking fires were 5%, 6%, 3%, and 70%, respectively (table 2). We also determined the risk attributable to EBV replication status using an NPC prevalence rate (59/100,000, IgA+ proportion (5%) in the general population, IgA+ rate (95%) in NPC cases and the incident of NPC (4.6%) in IgA+ population in the geographic catchment area of this study10. The attributable risk of NPC due to IgA+ status was 93% and explained fraction (EF) was 32.2%. In contrast, the family history and environmental risk factors cumulatively explained only 2.7% of NPC.

Since 15% of the NPC cases were KSCC, we sought to determine whether the risk factors were significantly different between KSCC and NKC. We found a significant association between preserved meat and NPC-KSCC but not with NPC-NKC—other factors were not significantly different between the two forms of NPC.

Discussion

The present study enrolled participants from a catchment area of 6 million people in southern China reporting one of the world’s highest NPC prevalence rates. The peak age of NPC at diagnosis was 35 to 55 years old with 96% of NPC cases seropositive for EBV/IgA/VCA antibodies in agreement with previous sampling38. Significant risk predictors for NPC include: 1) first, second or third degree relative with NPC; 2) diet that included consumption of salty fish 3 or more times a month; 3) exposure to home wood cooking fires; and 4) occupational exposures to solvents.

In the catchment area over 95% of NPC cases were EBV/IgA/VCA antibody positive compared to only 5% of the general population. Our study is unique in that we compared NPC cases who were EBV/IgA/VCA antibody positive to controls who were also EBV/IgA/VCA antibody positive to determine familial and environmental factors associated with NPC in the setting of active EBV replication. To our knowledge this is the largest investigation to date to systematically evaluate the role of NPC family history, salty fish, preserved meat, domestic and occupational exposures on risk of NPC in NPC high-risk population. EBV is widely believed to be a necessary (but not sufficient) cause of NPC, EBV/IgA/VCA antibodies have been used as a prospective marker of NPC in southern China for over two decades39-42. However, as we show in this study, EBV/IgA/VCA antibody status explains only 32% portion of the risk. Our findings indicated that EBV/IgA/VCA titer may offer a quantitative indicator for NPC risk as titers are significantly higher in NPC cases than in EBV/IgA/VCA controls (p <0.0001, Fig. 2).

Consistent with many other studies in southeast Asia that report that 6 to 8% of NPC have a first degree relative with NPC in NPC cases14, 21, 43, we also found that 7% of NPC cases had a first degree relative with NPC. In the absence of twin studies, it is not possible to determine if the recurrence rate in families is due to shared genetic or shared environmental factors or both. There were no significant differences on sex, age onset, tumor histological types and clinical stages between familial and nonfamilial NPC, confirming previous reports13, 43. Several researchers have reported the excess risk was from 6 to 19-fold among individuals with a first-degree relatives of NPC21, 43, 44, much more than we estimate in the present study possibly because those studies were not controlling for EBV/IgA/VCA antibody status. It is also possible that recall bias may at least partially explain discrepancies among the studies. A recent prospective study in Singapore reported a 2- to 3-fold increased risk of NPC among first-degree relative with NPC20, similar to our results.

Salted fish consumption has been consistently reported to be moderate to strong risk predictor of NPC in Southern China in a series of small studies enrolling fewer than 300 cases from 1983-1998 14-16, 19, 27, 45, 46. A large study (935 NPC subjects) in Shanghai, China also reported that dietary salted fish was a risk factor for NPC in Shanghai, China17. NPC risk is also moderately associated with other preserved foods3. Along with economic development after 1978, there has been a gradual and current change in eating habits and life style in China. Our data show that less than one third of population were eating salted fish or preserved meat at enrollment and heavy consumption of these food products is less than 4% in the control group. This study provides evidence that only regular consumption (≥ 3 times/month) of salted fish is a significant NPC risk factor. The consumption of preserved meat was not significantly associated with risk of NPC after adjusting for all other factors in our study.

Although occupational exposures to solvents are uncommon in the general population, the use of wood as a domestic cooking fuel is very frequent in the countryside of southern China. About 98% of the study participants reported exposure to wood cooking fire—one of the strongest risk predictors for NPC in this study, confirming an earlier report from the same region46. Those exposed to wood fire for more than 10 years had a nearly 6-fold excess risk of NPC.

Formaldehyde is known to cause tumors by experimental observation in rodents47, 48, but epidemiologic evidence in human is limited, especially in the NPC endemic region. A meta-analysis of available studies suggested that formaldehyde exposure was associated with a 2-fold increase in risk of NPC49. In our study population, only 6% of the population reported unspecified, occupational solvent exposure. This study confirms earlier studies that individuals seropositive for EBV/VCA/IgA are at a 2-fold greater risk of developing NPC if they are exposed to solvents in the workplace 23, 32. Here (table 2) and in two earlier studies23, 32 an association is apparent for short (≤ 10 years), but not long-term exposure to solvents. The lack of association between NPC and long term exposure (>10 years) may reflect a frailty bias; e.g., long term exposure to solvents to may lead to mortality due to other causes.

The populations in Southern China are exposed to multiple environmental risk factors. Our results show that a combination of risk factors increased the risk of NPC in the 5% of the population that are also EBV/IgA/VCA seropositive (table 3, 4). Our results indicate that the AR of wood fire exposure for NPC is 70%; however, the AR measures how much of one disease state can be attributed to a given factor, but not how much of the absence of the disease state can be attributed to the absence of the factor. This study shows that in high risk population who were EBV/IgA/VCA positive, only 2.7% of NPC can be explained by family history with NPC, consumption of salted fish, exposure to domestic wood fires, and exposure to occupational solvents. Clearly, there are additional causal influences yet to be discovered, including genetic factors, which determine susceptibility to nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the EBC/IgA/VCA positive population. These results may provide the basis for a quantitative risk assessment instrument to screen the EBV/IgA/VCA seropositive population in endemic areas for NPC risk.

We did not find that cigarette smoking was associated with NPC risk. This result is consistent with some previous studies reporting that smoking is not a risk factor for NPC in endemic areas 14, 25, 46, 50. A population-based case-control study in the United States reported an association between cigarette smoking and keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (KSCC) of NPC, but there was no evidence that non-keratinizing carcinoma (NKC) were associated with cigarette smoking24. In our cases, 15% of NPC patients were KSCC. We analysis the association stratified by the histologic type and observed no associations between smoking, intensity of smoking and KSCC or NKC in either the unadjusted or adjusted analysis (data not shown).

A limitation of our study may have been recall bias—particularly for childhood exposures to wood fires or dietary fish. Family members may also not have precise knowledge of family members with NPC. During the face to face interview, the interviewers found most volunteers were not confident in recalling the events that occurred in childhood or early adulthood, such as childhood consumption salty fish, preserved meat or age smoking was initiated. We did not include questions which may not be accurate due to obvious recall bias. Although lower social class or educational level may be considered as a risk factor of NPC, it is difficult to define socio-economic status during a period of rapid economic development in China during past 30 years. For remediation, all the samples we collected came from same geographic region and the cases and controls were matched by district. Although 81.6% of NPC cases were prevalent, 97% of the prevalent cases developed NPC within 3-4 years of study. It is therefore unlikely that entry recall bias for recent events is different between seroprevalent and seroincident NPC cases. The positive associations between dietary salty fish and wood-cooking fires and NPC may be due to other socio-economic factors tracked by these exposures.

In summary, we observed a consistent association between NPC family history, consumption of salted fish, exposure to domestic wood fire, and occupational exposures to solvents with NPC risk in southern China. Familial aggregation among family members suggests that, in addition to viral and environmental factors, predisposing genetic factors may be important. An understanding of the interactions among genetic, viral, and environmental factors will lead to a better understanding of the carcinogenic pathways leading to NPC and provide insights into improving therapeutic options. In addition, this study indicates that public health policy aimed at reducing exposures to nitrosamines found in preserved foods, wood cooking fires, and solvents will reduce incidence of NPC.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues, Drs. James Lautenberger for invaluable statistical advice, Mr. Bailey Kessing for efficient data management, and Ms. Jan Martenson for her organizational expertise and her assistance in developing the questionnaire.

Grant support: This research was supported in part or in whole with national natural science foundation of China, grant #30672377. This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract N01-CO-12400. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Journal category: Epidemiology

This study systemically investigated environmental risk factors for nasopharyngeal carcinoma in high risk-population seropositive for IgA antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus capsid antigen —a predictive marker for NPC in Chinese populations. The attributable risk and explained fraction have been calculated showing that while the attributable risk for several of the exposures is large, these exposures explain less than 3% of the variance observed in NPC development.

References

- 1.Wu JJ, Guo H, Su R. Analysis and forecast of incidence and mortality of nasopharynx cancer by time series in Zhongshan city. Chinese Hospital Statistic. 2001;8:16–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jia WH, Huang QH, Liao J, Ye W, Shugart YY, Liu Q, Chen LZ, Li YH, Lin X, Wen FL, Adami HO, Zeng Y, et al. Trends in incidence and mortality of nasopharyngeal carcinoma over a 20-25 year period (1978/1983-2002) in Sihui and Cangwu counties in southern China. BMC cancer. 2006;6:178. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang ET, Adami HO. The enigmatic epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1765–77. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee AW, Foo W, Mang O, Sze WM, Chappell R, Lau WH, Ko WM. Changing epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Hong Kong over a 20-year period (1980-99): an encouraging reduction in both incidence and mortality. International journal of cancer. 2003;103:680–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li LD, Lu FZ, Zhang SW, Mu R, Sun XD, Huangpu XM, Sun J, Zhou YS, Ouyang NH, Rao KQ, Chen YD, Sun AM, et al. Trends and recent prediction in mortality of cancer during 20 years in China. Chin J Oncol. 1997;19:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dai XD, Li LD, Lu FZ, Zhang SW, Sun J, Lin YJ, Sun XW, Shi YP. Trends and recent prediction in mortality of nasopharyngeal carcinoma during 20 years in China. J Pract. Oncol. 1999;13:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hildesheim A, Levine PH. Etiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a review. Epidemiologic reviews. 1993;15:466–85. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henle G, Henle W. Epstein-Barr virus-specific IgA serum antibodies as an outstanding feature of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. International journal of cancer. 1976;17:1–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910170102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raab-Traub N. Epstein-Barr virus in the pathogenesis of NPC. Seminars in cancer biology. 2002;12:431–41. doi: 10.1016/s1044579x0200086x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeng Y, Deng H. A 10-year prospective study on nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Wuzhou City and Cangwu County, Guangxi, China. In: Tursz T, Pagano JS, Ablashi DV, De The G, Lenoir G, Pearson GR, editors. The Epstein-Barr Virus and Associated Diseases. Colloque INSERM/John Libbey Eurotext; 1993. pp. 735–41. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown TM, Heath CW, Lang RM, Lee SK, Whalley BW. Nasopharyngeal cancer in Bermuda. Cancer. 1976;37:1464–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197603)37:3<1464::aid-cncr2820370331>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coffin CM, Rich SS, Dehner LP. Familial aggregation of nasopharyngeal carcinoma and other malignancies. A clinicopathologic description. Cancer. 1991;68:1323–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910915)68:6<1323::aid-cncr2820680623>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loh KS, Goh BC, Lu J, Hsieh WS, Tan L. Familial nasopharyngeal carcinoma in a cohort of 200 patients. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:82–5. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu MC, Ho JH, Lai SH, Henderson BE. Cantonese-style salted fish as a cause of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: report of a case-control study in Hong Kong. Cancer research. 1986;46:956–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu MC, Huang TB, Henderson BE. Diet and nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a case-control study in Guangzhou, China. International journal of cancer. 1989;43:1077–82. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910430621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armstrong RW, Imrey PB, Lye MS, Armstrong MJ, Yu MC, Sani S. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Malaysian Chinese: salted fish and other dietary exposures. International journal of cancer. 1998;77:228–35. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980717)77:2<228::aid-ijc11>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan JM, Wang XL, Xiang YB, Gao YT, Ross RK, Yu MC. Preserved foods in relation to risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Shanghai, China. International journal of cancer. 2000;85:358–63. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000201)85:3<358::aid-ijc11>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zou J, Sun Q, Akiba S, Yuan Y, Zha Y, Tao Z, Wei L, Sugahara T. A case-control study of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the high background radiation areas of Yangjiang, China. Journal of radiation research. 2000;41(Suppl):53–62. doi: 10.1269/jrr.41.s53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu MC, Mo CC, Chong WX, Yeh FS, Henderson BE. Preserved foods and nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a case-control study in Guangxi, China. Cancer research. 1988;48:1954–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friborg JT, Yuan JM, Wang R, Koh WP, Lee HP, Yu MC. A prospective study of tobacco and alcohol use as risk factors for pharyngeal carcinomas in Singapore Chinese. Cancer. 2007;109:1183–91. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu MC, Garabrant DH, Huang TB, Henderson BE. Occupational and other non-dietary risk factors for nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Guangzhou, China. International journal of cancer. 1990;45:1033–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910450609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng YJ, Hildesheim A, Hsu MM, Chen IH, Brinton LA, Levine PH, Chen CJ, Yang CS. Cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Taiwan. Cancer Causes Control. 1999;10:201–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1008893109257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.West S, Hildesheim A, Dosemeci M. Non-viral risk factors for nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the Philippines: results from a case-control study. International journal of cancer. 1993;55:722–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910550504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaughan TL, Shapiro JA, Burt RD, Swanson GM, Berwick M, Lynch CF, Lyon JL. Nasopharyngeal cancer in a low-risk population: defining risk factors by histological type. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1996;5:587–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sriamporn S, Vatanasapt V, Pisani P, Yongchaiyudha S, Rungpitarangsri V. Environmental risk factors for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a case-control study in northeastern Thailand. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1992;1:345–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng X, Yan L, Nilsson B, Eklund G, Drettner B. Epstein-Barr virus infection, salted fish and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. A case-control study in southern China. Acta Oncol. 1994;33:867–72. doi: 10.3109/02841869409098448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ning JP, Yu MC, Wang QS, Henderson BE. Consumption of salted fish and other risk factors for nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) in Tianjin, a low-risk region for NPC in the People's Republic of China. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1990;82:291–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaughan TL, Stewart PA, Teschke K, Lynch CF, Swanson GM, Lyon JL, Berwick M. Occupational exposure to formaldehyde and wood dust and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Occupational and environmental medicine. 2000;57:376–84. doi: 10.1136/oem.57.6.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Armstrong RW, Imrey PB, Lye MS, Armstrong MJ, Yu MC, Sani S. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Malaysian Chinese: occupational exposures to particles, formaldehyde and heat. International journal of epidemiology. 2000;29:991–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.6.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marsh GM, Youk AO, Buchanich JM, Cassidy LD, Lucas LJ, Esmen NA, Gathuru IM. Pharyngeal cancer mortality among chemical plant workers exposed to formaldehyde. Toxicology and industrial health. 2002;18:257–68. doi: 10.1191/0748233702th149oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marsh GM, Youk AO. Reevaluation of mortality risks from nasopharyngeal cancer in the formaldehyde cohort study of the National Cancer Institute. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2005;42:275–83. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hildesheim A, Dosemeci M, Chan CC, Chen CJ, Cheng YJ, Hsu MM, Chen IH, Mittl BF, Sun B, Levine PH, Chen JY, Brinton LA, et al. Occupational exposure to wood, formaldehyde, and solvents and risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:1145–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li W, Ray RM, Gao DL, Fitzgibbons ED, Seixas NS, Camp JE, Wernli KJ, Astrakianakis G, Feng Z, Thomas DB, Checkoway H. Occupational risk factors for nasopharyngeal cancer among female textile workers in Shanghai, China. Occupational and environmental medicine. 2006;63:39–44. doi: 10.1136/oem.2005.021709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng H, Zeng Y, Lei Y, Zhao Z, Wang P, Li B, Pi Z, Tan B, Zheng Y, Pan W, et al. Serological survey of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in 21 cities of south China. Chin Med J (Engl) 1995;108:300–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo XC, Scott K, Liu Y, Dean M, David V, Nelson GW, Johnson RC, Dilks HH, Lautenberger J, Kessing B, Martenson J, Guan L, et al. Genetic factors leading to chronic Epstein-Barr virus infection and nasopharyngeal carcinoma in South East China: study design, methods and feasibility. Hum Genomics. 2006;2:365–75. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-2-6-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson GW, O'Brien SJ. Using mutual information to measure the impact of multiple genetic factors on AIDS. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2006;42:347–54. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000219786.88786.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ou SH, Zell JA, Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H. Epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the United States: improved survival of Chinese patients within the keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma histology. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:29–35. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo X, O'Brien SJ, Zeng Y, Nelson GW, Winkler CA. GSTM1 and GSTT1 Gene Deletions and the Risk for Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma in Han Chinese. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1760–3. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeng Y, Pi GH, Deng H, Zhang JM, Wang PC, Wolf H, De The G. 1986;2(Suppl 1):S7–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zeng Y, Liu Y, Liu C, Chen S, Wei J, Zhu J, Zai H. Application of immunoenzymic method and immunoautoradiographic method for the mass survey of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Chin J Oncol. 1979;1:2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeng Y, Zhang LG, Li HY, Jan MG, Zhang Q, Wu YC, Wang YS, Su GR. Serological mass survey for early detection of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Wuzhou City, China. International journal of cancer. 1982;29:139–41. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910290204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeng Y, Zhang LG, Wu YC, Huang YS, Huang NQ, Li JY, Wang YB, Jiang MK, Fang Z, Meng NN. Prospective studies on nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Epstein-Barr virus IgA/VCA antibody-positive persons in Wuzhou City, China. International journal of cancer. 1985;36:545–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910360505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ung A, Chen CJ, Levine PH, Cheng YJ, Brinton LA, Chen IH, Goldstein AM, Hsu MM, Chhabra SK, Chen JY, Apple RJ, Yang CS, et al. Familial and sporadic cases of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Taiwan. Anticancer research. 1999;19:661–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen CJ, Liang KY, Chang YS, Wang YF, Hsieh T, Hsu MM, Chen JY, Liu MY. Multiple risk factors of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Epstein-Barr virus, malarial infection, cigarette smoking and familial tendency. Anticancer research. 1990;10:547–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Armstrong RW, Armstrong MJ, Yu MC, Henderson BE. Salted fish and inhalants as risk factors for nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Malaysian Chinese. Cancer research. 1983;43:2967–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng YM, Tuppin P, Hubert A, Jeannel D, Pan YJ, Zeng Y, de The G. Environmental and dietary risk factors for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a case-control study in Zangwu County, Guangxi, China. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:508–14. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swenberg JA, Kerns WD, Mitchell RI, Gralla EJ, Pavkov KL. Induction of squamous cell carcinomas of the rat nasal cavity by inhalation exposure to formaldehyde vapor. Cancer research. 1980;40:3398–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Albert RE, Sellakumar AR, Laskin S, Kuschner M, Nelson N, Snyder CA. Gaseous formaldehyde and hydrogen chloride induction of nasal cancer in the rat. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1982;68:597–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Partanen T. Formaldehyde exposure and respiratory cancer--a meta-analysis of the epidemiologic evidence. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1993;19:8–15. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee HP, Gourley L, Duffy SW, Esteve J, Lee J, Day NE. Preserved foods and nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a case-control study among Singapore Chinese. International journal of cancer. 1994;59:585–90. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910590502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]