Abstract

Purpose

Brain metastasis is the most common complication of brain cancer; nevertheless, primary lung cancer accounts for approximately 20%–40% of brain metastases cases. Surgical resection is the preferred treatment for brain metastases. However, no studies have reported the outcome of surgical resection of brain metastases from non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in the People’s Republic of China. Moreover, the optimal treatment for primary NSCLC in patients with synchronous brain metastases is hitherto controversial.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively analyzed the cases of NSCLC patients with brain metastases who underwent neurosurgical resection at the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, and assessed the efficacy of surgical resection and the necessity of aggressive treatment for primary NSCLC in synchronous brain metastases patients.

Results

A total of 62 patients, including 47 men and 15 women, with brain metastases from NSCLC were enrolled in the study. The median age at the time of craniotomy was 54 years (range 29–76 years). At the final follow-up evaluation, 50 patients had died. The median OS time was 15.1 months, and the survival rates were 70% and 37% at 1 and 2 years, respectively. The median OS time of synchronous brain metastases patients was 12.5 months. Univariate analysis revealed that radical treatment of primary NSCLC was positively correlated with survival, and it was an independent prognostic factor in the multivariate analysis.

Conclusion

Surgical resection is an effective treatment for brain metastases. Besides craniotomy, radical therapy is necessary for the management of primary NSCLC in patients with synchronous brain metastases.

Keywords: synchronous brain metastases, neurosurgery, whole-brain radiation therapy

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide; it accounted for 13% (1.6 million) of the total diagnosed cancer cases and 18% (1.4 million) of total cancer-related deaths in 2008.1 In the USA, it accounts for 26% and 28% of all cancer-related deaths among women and men, respectively.2 Non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), including its types adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, large-cell carcinoma, and bronchioloalveolar carcinoma, accounts for nearly 85% of all lung cancer cases.3 The risk of developing brain metastases is up to 10% for patients in the early stages of NSCLC.4 Furthermore, brain metastasis occurs in 30%–50% patients with advanced NSCLC.5,6

The development of brain metastases is often considered as the terminal stage of any cancer, and the prognosis of patients with brain metastases from NSCLC is generally poor. Without treatment, the median survival time is only 1 month.7 Whole-brain radiation therapy (WBRT) alone can extend the median survival time to 3–6 months.8,9 Two randomized control trials have reported that patients with extracranial primary cancer and single brain metastasis who underwent surgical resection followed by WBRT had longer survival time and better quality of life than did similar patients who underwent WBRT alone.8,10 Nevertheless, the median survival time of patients undergoing combination therapy is also not more than 1 year. Thus, management of brain metastasis continues to be a significant challenge in the treatment of NSCLC.

No studies have hitherto reported the outcomes of NSCLC patients in the People’s Republic of China who underwent surgical treatment for brain metastases in the People’s Republic of China. In the present study, we retrospectively analyzed the cases of patients with brain metastases from NSCLC who underwent neurosurgical resection at a single hospital, and assessed the efficacy of this treatment and the necessity of radical treatment for primary NSCLC in patients with synchronous brain metastases.

Materials and methods

Patients

We analyzed the cases of NSCLC patients who underwent craniotomy for brain metastases between January 2000 and June 2012 at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. Brain metastases were diagnosed using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and serial MRI was used for follow up. Clinical parameters included patient demographics, number of brain metastases, location of brain metastases, tumor histology, treatment modality, and thoracic disease stage and treatment. Additionally, recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) was performed to facilitate stage classification.11 Patients <65 years old with Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) ≥70, controlled primary cancer, and no extracranial metastases were grouped under class 1. Class 3 included all patients with KPS <70. Patients not fitting any of the above-mentioned criteria were grouped under class 2. NSCLC stage was classified according to the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging criteria,12 excluding the metastases in the brain. Overall survival (OS) time was calculated as the duration between the time of diagnosis of brain metastases and death or the date of last follow up (November 2013) for patients who survived until the end of the analysis period. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS v16.0 software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Survival data were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method and logrank test. The Cox proportional hazard model was used to identify the independent prognostic factors for survival. P<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Patient demographics

A total of 62 patients, including 47 men and 15 women, with brain metastases from NSCLC were enrolled in the study. The median age at the time of craniotomy was 54 years (range 29–76 years). The histopathological subtype was adenocarcinoma in 50 patients, squamous cell carcinoma in eight patients, adenosquamous carcinoma in two patients, large-cell carcinoma in one patient, and bronchioloalveolar carcinoma in one patient. According to the NSCLC classification, 15 patients had stage I cancer, 19 had stage II cancer, and 28 had stage III cancer. Of these 62 patients, 49 had single brain metastasis, and 13 had two or more brain metastases. Only 22 patients had synchronous brain metastases from NSCLC. Synchronous presentation was defined as diagnosis of brain metastases within 2 months of diagnosis of NSCLC. According to RPA classification, 34 patients belonged to stage I; 20 belonged to stage II; and eight belonged to stage III. Patients’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Characteristic | All patients n=62 n (%) |

MBM n=40 n (%) |

SBM n=22 n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| <54 | 29 (46.8) | 18 (45.0) | 11 (55.0) |

| ≥54 | 33 (53.2) | 22 (55.0) | 11 (55.0) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 47 (75.8) | 32 (82.5) | 14 (63.6) |

| Female | 15 (24.2) | 8 (17.5) | 8 (36.4) |

| Histology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 49 (79.0) | 32 (80.0) | 17 (77.3) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 9 (14.5) | 6 (15.0) | 3 (13.6) |

| Others | 4 (6.5) | 2 (5.0) | 2 (9.1) |

| NSCLC stage | |||

| I | 15 (24.2) | 13 (32.5) | 2 (9.1) |

| II | 19 (30.6) | 13 (32.5) | 6 (27.3) |

| III | 28 (45.2) | 14 (35.0) | 14 (63.6) |

| Number of brain metastases | |||

| 1 | 49 (79.0) | 32 (80.0) | 17 (77.3) |

| ≥2 | 13 (21.0) | 8 (20.0) | 5 (22.7) |

| RPA | |||

| I | 34 (54.8) | 24 (60.0) | 10 (45.5) |

| II | 20 (32.3) | 11 (27.5) | 9 (40.9) |

| III | 8 (12.9) | 5 (12.5) | 3 (13.6) |

Abbreviations: MBM, metachronous brain metastases; NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer; RPA, recursive partitioning analysis; SBM, synchronous brain metastases.

Management of brain metastases

All symptomatic patients diagnosed with brain metastases and presenting with brain edema received intravenous dexamethasone. All patients underwent craniotomy, of which 50 underwent complete resection. For patients with two or more brain metastases, only a single life-threatening brain lesion was excised. A total of 45 patients underwent metastasectomy followed by WBRT, whereas nine patients with multiple brain metastases underwent stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) followed by metastasectomy. Eight patients underwent metastasectomy alone because of poor physical condition. The most commonly used fractionation schedule for WBRT was 30 Gy doses in 10 fractions. The median maximal and marginal doses for SRS were 36 Gy (range 32–40 Gy) and 18 Gy (range 14–24 Gy), respectively.

Management of lung cancer

Patients were considered to have had radical therapy if they underwent surgical resection and/or received sequential or concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Patients who received only chemotherapy for thoracic disease were considered to have had palliative thoracic therapy. A total 35 patients underwent lobectomy, eight underwent wedge resection, five underwent chemoradiotherapy, and seven patients only underwent chemotherapy. The various management approaches are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Management of lung cancer

| Management of lung cancer | All patients n=62 n (%) |

MBM n=40 n (%) |

SBM n=22 n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radical treatment | 48 (77.4) | 36 (85.0) | 10 (45.5) |

| Surgical resection | 43 (69.4) | 33 (77.5) | 9 (40.9) |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 5 (8.0) | 3 (7.5) | 1 (4.6) |

| Palliative treatment | 7 (11.3) | 4 (10.0) | 8 (36.4) |

| Supportive treatment | 7 (11.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (18.1) |

Abbreviations: MBM, metachronous brain metastases; SBM, synchronous brain metastases.

Outcomes and survival analysis

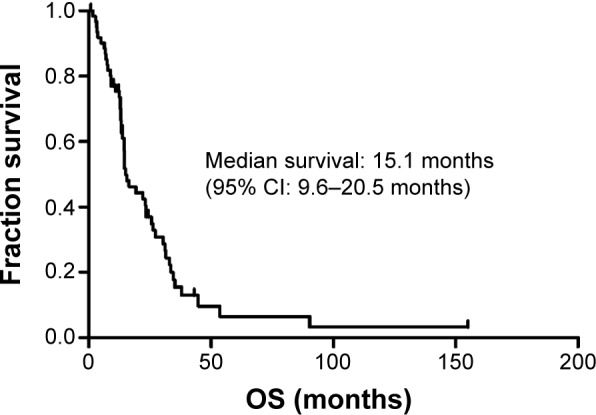

Kaplan–Meier analysis and logrank test were used to identify potential predictive factors of survival. At the final follow-up visit, 50 patients had died. Of these, 21 patients died from the progression of brain metastases, and 29 patients died because of systemic metastasis. The median OS time was 15.1 months, with survival rates of 70% and 37% at 1 and 2 years, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier analysis for overall survival of all patients.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OS, overall survival.

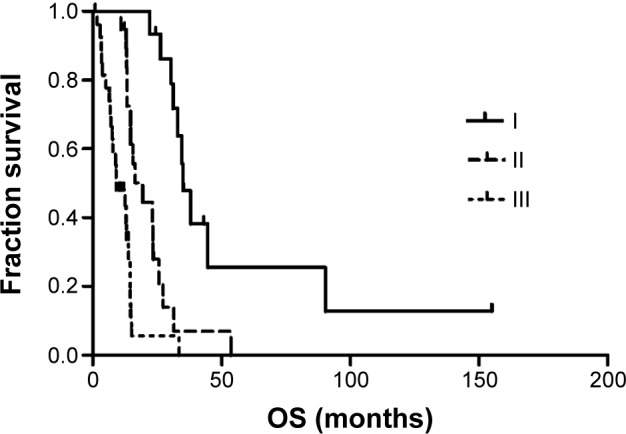

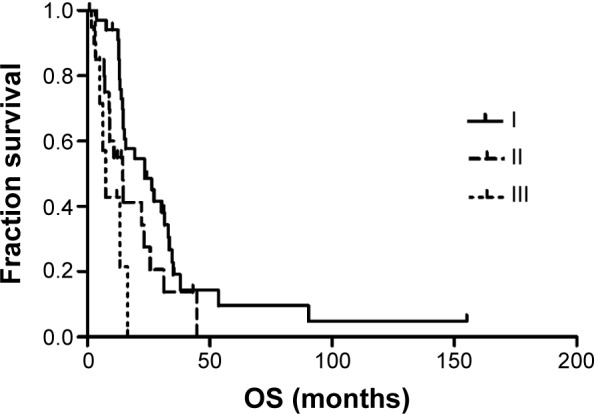

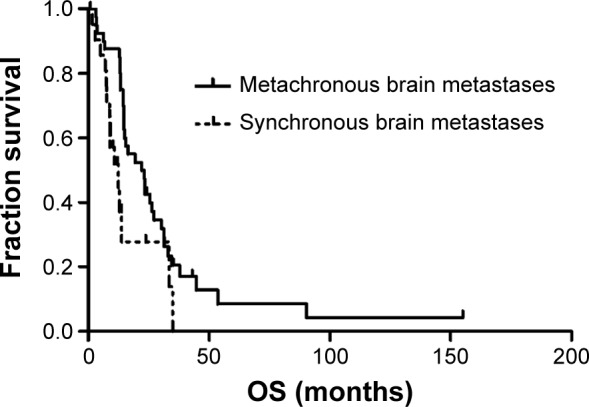

Table 3 shows the results of the univariate analysis for the prognostic factors of OS for all patients. The stage of primary NSCLC correlated with OS, with a median OS time of 34.9 months for stage I patients, 19.2 months for stage II patients, and 9.0 months for stage III patients (Figure 2). The RPA stage also correlated with OS, with a median OS of 23.4 months for stage I patients, 14.5 months for stage II patients, and 7.4 months for stage III patients (Figure 3). In addition, absence of synchronous brain metastases was associated with longer survival (Figure 4). The primary NSCLC (P<0.001) and RPA (P=0.001) stages were also independent prognostic factors in the multivariate analysis.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis to identify factors affecting overall survival of patients with brain metastases

| Variable | Cases | Median OS (months) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.235 | ||

| <54 | 29 | 19.2 | |

| ≥54 | 33 | 14.5 | |

| Sex | 0.790 | ||

| Male | 47 | 15.1 | |

| Female | 15 | 14.7 | |

| Histology | 0.148 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 49 | 22.0 | |

| Nonadenocarcinoma | 13 | 12.9 | |

| NSCLC stage | 0.000 | ||

| I | 15 | 34.9 | |

| II | 19 | 19.2 | |

| III | 28 | 9.0 | |

| Number of BM | 0.526 | ||

| 1 | 49 | 15.5 | |

| ≥2 | 13 | 14.7 | |

| RPA | 0.002 | ||

| I | 34 | 23.4 | |

| II | 20 | 14.5 | |

| III | 8 | 7.4 | |

| Synchronous BM | 0.015 | ||

| Yes | 22 | 12.5 | |

| No | 40 | 22.0 |

Abbreviations: BM, brain metastases; NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer; OS, overall survival; RPA, recursive partitioning analysis.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier analysis for overall survival by NSCLC stage.

Abbreviations: NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer; OS, overall survival.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier analysis for overall survival by RPA classification.

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; RPA, recursive partitioning analysis.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier analysis for overall survival of patients with synchronous and metachronous brain metastases.

Abbreviation: OS, overall survival.

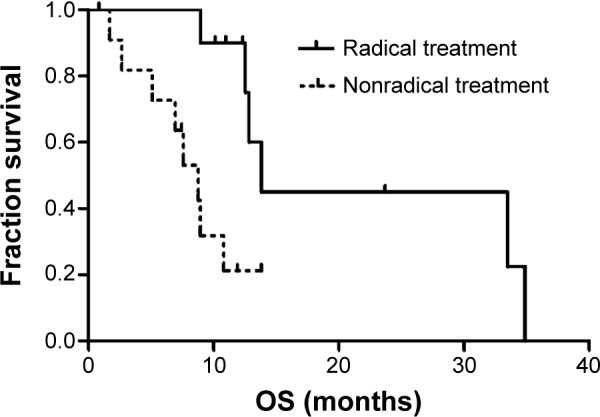

Table 4 shows the results of the univariate analysis for prognostic factors of OS for synchronous brain metastases patients. The median OS time for patients with synchronous brain metastases was 12.5 months. In the univariate analysis, radical treatment of primary NSCLC was found to be positively correlated with survival (P=0.005) and was an independent prognostic factor in the multivariate analysis (P=0.007) (Table 4 and Figure 5). Stage I and II NSCLC patients achieved longer survival than stage III patients (P=0.020); however, NSCLC stage was not an independent prognostic factor in the multivariate analysis (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate analysis to identify factors affecting overall survival of patients with synchronous brain metastases

| Variable | Cases | Median OS (months) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.144 | ||

| <54 | 10 | 13.8 | |

| ≥54 | 12 | 10.8 | |

| Sex | 0.746 | ||

| Male | 16 | 10.8 | |

| Female | 6 | 34.9 | |

| NSCLC stage | 0.020 | ||

| I and II | 7 | 34.9 | |

| III | 15 | 8.9 | |

| Number of brain metastases | 0.515 | ||

| 1 | 16 | 12.5 | |

| ≥2 | 6 | 8.8 | |

| Management of lung cancer | 0.005 | ||

| Radical treatment | 10 | 13.8 | |

| Nonradical treatment | 12 | 8.7 |

Abbreviations: NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer; OS, overall survival.

Figure 5.

Kaplan–Meier analysis for overall survival by type of treatment for primary NSCLC in patients with synchronous brain metastases.

Abbreviations: NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer; OS, overall survival.

Discussion

Lung cancer burden in People’s Republic of China is continuously increasing because of an increased aging population, smoking habits, and air pollution. Brain metastasis is the most common complication of brain cancer; however, approximately 20%–40% of brain metastases originate from lung cancer.13,14 As the incidence rates for various cancers increases and mortality from cancers decreases, the incidence rates of brain metastases appear to be increasing.

Since 2000, our center has been the first in the People’s Republic of China to systematically treat brain metastases. Surgical resection followed by WBRT has become the standard management practice for brain metastases patients. In the present study, we retrospectively analyzed the cases of patients from a single center who underwent craniotomy for brain metastases from NSCLC. A median OS time of 15.1 months could be achieved for all patients, and the survival rates at 1 and 2 years were 70% and 37%, respectively. Consistent with published data,8,10,15 we found that surgical resection could prolong survival and improve quality of life. Especially in patients with significant mass effect, surgical resection could relieve edema secondary to brain metastases and rapidly increase intracranial pressure to allow sufficient time for further treatment.

Low stages of primary NSCLC and RPA and absence of synchronous brain metastases were also associated with significantly longer survival times. However, there was no significant difference between the survival of single and multiple brain metastases patients. Of the 13 patients with multiple brain metastases, nine patients underwent SRS and four patients received chemotherapy followed by metastasectomy. They had a median OS time of 14.7 months. SRS offers a minimally invasive option to treat unresectable multiple brain metastases; therefore, patients with multiple lesions but a low total volume of disease can be treated with SRS.16–18 Nevertheless, surgical resection remains the primary approach for larger brain lesions that are accessible.17,19

The optimal treatment for primary NSCLC after aggressive management of brain metastases is hitherto controversial. Many studies have focused on the treatment of synchronous brain metastases from NSCLC.20–23 Lind et al suggested that radical thoracic treatment is acceptable for patients <65 years who are eligible to undergo surgery/radiosurgery for synchronous brain metastases from NSCLC.20 Bonnette et al reported that after complete resection of a single brain metastasis, it is legitimate to proceed with lung resection.22 Furthermore, Hu et al recommended aggressive treatment of the primary lung cancer, particularly for stage I NSCLC patients with single brain metastasis.21

Consistent with these studies, we found that patients who received radical treatment of primary NSCLC had a significantly longer OS (13.8 months) than did those receiving nonradical treatment (8.7 months). In addition, stage I and II NSCLC patients (34.9 months) had a significantly longer survival than did stage III patients (8.9 months). Thus, radical treatment was necessary for certain patients who could undergo sequential or concurrent chemoradiotherapy for primary NSCLC.

The present study had certain limitations. First, some selection bias could have been introduced because of the low sample size, and additional studies using a large sample size are necessary to substantiate the findings of our study. Second, the effect of chemotherapy could not be assessed because of the heterogeneous chemotherapy courses employed in our patients. Prospective clinical trials employing a standardized chemotherapy course will be required to evaluate the effect of chemotherapy on prognosis.

In summary, the findings of our study suggest that surgical resection is an effective treatment for brain metastases from NSCLC. With the establishment of novel neurosurgical techniques, neurosurgery could provide diverse treatment options for brain metastases. Moreover, radical therapy for primary NSCLC is necessary in addition to craniotomy for patients with synchronous brain metastases patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Wu Jieping Medical Foundation [grant number 320675012373]; The Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province, China [grant number Z012B031800382]; National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 81401908].

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramalingam SS, Owonikoko TK, Khuri FR. Lung cancer: New biological insights and recent therapeutic advances. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):91–112. doi: 10.3322/caac.20102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hubbs JL, Boyd JA, Hollis D, Chino JP, Saynak M, Kelsey CR. Factors associated with the development of brain metastases: analysis of 975 patients with early stage nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2010;116(21):5038–5046. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mamon HJ, Yeap BY, Jänne PA, et al. High risk of brain metastases in surgically staged IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(7):1530–1537. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsiao SH, Chung CL, Chou YT, Lee HL, Lin SE, Liu HE. Identification of subgroup patients with stage IIIB/IV non-small cell lung cancer at higher risk for brain metastases. Lung Cancer. 2013;82(2):319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lagerwaard FJ, Levendag PC, Nowak PJ, Eijkenboom WM, Hanssens PE, Schmitz PI. Identification of prognostic factors in patients with brain metastases: a review of 1,292 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43(4):795–803. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00442-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Walsh JW, et al. A randomized trial of surgery in the treatment of single metastases to the brain. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(8):494–500. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199002223220802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mintz AH, Kestle J, Rathbone MP, et al. A randomized trial to assess the efficacy of surgery in addition to radiotherapy in patients with a single cerebral metastasis. Cancer. 1996;78(7):1470–1476. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19961001)78:7<1470::aid-cncr14>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vecht CJ, Haaxma-Reiche H, Noordijk EM, et al. Treatment of single brain metastasis: radiotherapy alone or combined with neurosurgery? Ann Neurol. 1993;33(6):583–590. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaspar L, Scott C, Rotman M, et al. Recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) of prognostic factors in three Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) brain metastases trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37(4):745–751. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaal EC, Niël CG, Vecht CJ. Therapeutic management of brain metastasis. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(5):289–298. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Sloan AE, Davis FG, Vigneau FD, Lai P, Sawaya RE. Incidence proportions of brain metastases in patients diagnosed (1973 to 2001) in the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance System. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(14):2865–2872. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muacevic A, Wowra B, Siefert A, Tonn JC, Steiger HJ, Kreth FW. Microsurgery plus whole brain irradiation versus Gamma Knife surgery alone for treatment of single metastases to the brain: a randomized controlled multicentre Phase III trial. J Neurooncol. 2008;87(3):299–307. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9510-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman WA. Expanding indications for stereotactic radiosurgery in the treatment of brain metastases. Neurosurgery. 2013;60(Suppl 1):S9–S12. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000430329.25516.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baschnagel AM, Meyer KD, Chen PY, et al. Tumor volume as a predictor of survival and local control in patients with brain metastases treated with Gamma Knife surgery. J Neurosurg. 2013;119(5):1139–1144. doi: 10.3171/2013.7.JNS13431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohammadi AM, Recinos PF, Barnett GH, et al. Role of Gamma Knife surgery in patients with 5 or more brain metastases. J Neurosurg. 2012;117(Suppl):S5–S12. doi: 10.3171/2012.8.GKS12983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang HC, Kano H, Lunsford LD, Niranjan A, Flickinger JC, Kondziolka D. What factors predict the response of larger brain metastases to radiosurgery? Neurosurgery. 2011;68(3):682–690. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318207a58b. discussion 690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lind JS, Lagerwaard FJ, Smit EF, Postmus PE, Slotman BJ, Senan S. Time for reappraisal of extracranial treatment options? Synchronous brain metastases from nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(3):597–605. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu C, Chang EL, Hassenbusch SJ, et al. Nonsmall cell lung cancer presenting with synchronous solitary brain metastasis. Cancer. 2006;106(9):1998–2004. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonnette P, Puyo P, Gabriel C, et al. Groupe Thorax Surgical management of non-small cell lung cancer with synchronous brain metastases. Chest. 2001;119(5):1469–1475. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.5.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee DH, Han JY, Kim HT, et al. Primary chemotherapy for newly diagnosed nonsmall cell lung cancer patients with synchronous brain metastases compared with whole-brain radiotherapy administered first: result of a randomized pilot study. Cancer. 2008;113(1):143–149. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]