Abstract

Endothelial cell (EC) aging and senescence are key events in atherogenesis and cardiovascular disease development. Age-associated changes in the local mechanical environment of blood vessels have also been linked to atherosclerosis. However, the extent to which cell senescence affects mechanical forces generated by the cell is unclear. In this study, we sought to determine whether EC senescence increases traction forces through age-associated changes in the glycocalyx and antioxidant regulator deacetylase Sirtuin1 (SIRT1), which is downregulated during aging. Traction forces were higher in cells that had undergone more population doublings and changes in traction force were associated with altered actin localization. Older cells also had increased actin filament thickness. Depletion of heparan sulfate in young ECs elevated traction forces and actin filament thickness, while addition of heparan sulfate to the surface of aged ECs by treatment with angiopoietin-1 had the opposite effect. While inhibition of SIRT1 had no significant effect on traction forces or actin organization for young cells, activation of SIRT1 did reduce traction forces and increase peripheral actin in aged ECs. These results show that EC senescence increases traction forces and alters actin localization through changes to SIRT1 and the glycocalyx.

Keywords: Sirtuin1, heparan sulfate, vascular mechanobiology, actin

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is the primary pathology underlying cardiovascular disease and its development has been attributed to both changes in the local mechanical environment and endothelial cell (EC) aging. Changes in vessel composition and structure have been linked to the development and progression of atherosclerosis.58 There is also evidence of accelerated aging in atheroprone regions, including the presence of giant cells,4 elevated levels of β-galactosidase staining,34 and telomere shortening.37 Aging in atheroprone regions is likely due to high oxidative stress17 which causes apoptosis. The resulting increase in cell turnover leads to an increase in EC replication. The increased oxidative stress and EC replication can lead to localized senescence. Further, aging endothelium exhibits increased permeability to macromolecules11 and increased sensitivity to oxidative stress.10 A localized increase in the permeability of the endothelial layer to proteins24 is one of the earliest events in atherosclerosis development and influences the progression of atherosclerosis.36, 52

Traction forces in ECs play an important role in cell migration and adhesion, with forces being highest at the periphery of the cell.43 Bovine aortic ECs on stiff substrates had increased cell traction forces and permeability compared to those seeded on soft substrates.28 This result correlated with increased actomyosin contractility for cells isolated from old mice. This increase in contractility, traction force, and permeability could be reversed through inhibition of the Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) pathway.28

The environment surrounding the lesion tends to be highly oxidative. This is due to local variations in shear stress leading to the development of oscillatory and reversing flows that increase oxidative stress through NADPH-dependent oxidase,50 and is exacerbated by elevated levels of lipids and cholesterol. In vitro, exposure of ECs to oxidative stress from H2O2 treatment elevated their permeability. 5, 10, 38 Reactive oxygen species regulate the dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton35 and cell traction forces.32 Oxidative stress can disrupt the glycocalyx – a thin layer of glycoproteins and proteoglycans on the surface of endothelial cells both in vitro and in vivo.56,33 Damage to the glycocalyx can increase endothelial permeability and impair shear-mediated NO production.44, 48, 56

SIRT1 is a deacetylase that regulates antioxidant activity and the cellular energy balance. Levels of SIRT1 are reduced during aging or due to exposure to oxidative stress and disturbed fluid flow in atheroprone regions.9 Activation of SIRT1 reverses several age-associated phenotypes.10, 11, 40, 66 In ApoE-knockout mice, overexpression of SIRT1 in ECs decreased atherosclerosis.40 Furthermore, SIRT1 may regulate permeability through regulation of cell junction proteins, such as occludin.11

While changes in the mechanical environment and cell aging impact atherosclerosis development, the relationship between the two remains unclear. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that age-associated changes in the EC glycocalyx or SIRT1 increase cell traction forces due to changes in actin localization and actin filament thickness. To test this hypothesis, we used human cord blood-derived ECs (hCB-ECs) as a model for cell aging because of their low, physiological permeability at low population doublings,11 high proliferative potential in subconfluent cultures,11 and similarity to arterial ECs.3 We examined traction forces of aging ECs and assessed their dependence on activators and inhibitors of SIRT1 and heparan sulfate. We also examined the effect of these agents on the actin cytoskeleton.

Methods

Cell Culture

Human umbilical cord blood derived endothelial cells (hCB-ECs) were isolated from blood as previously described by Ingram et al.30 For isolation of hCB-ECs, umbilical cord blood was obtained from the Carolina Cord Blood Bank (n=3 donors). Prior to receipt, all patient identifiers were removed. The Duke University Health System IRB has determined that this protocol meets the definition of research not involving human subjects as described in 45 CFR 46.102(f), 21 CFR 56.102(e) and 21 CFR 812.3(p) and satisfies the Privacy Rule as described in 45CFR164.514.

After collection, blood was diluted 1:1 with Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS, Invitrogen), placed onto Histopaque 1077 (Sigma), and centrifuged at 740xg for 30 minutes. Buffy coat mononuclear cells were collected and washed three times with “complete EC growth medium,” comprising 8% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS) added to Endothelial Basal Media-2 (Cambrex) supplemented with Endothelial Growth Media-2 SingleQuots (containing 2% FBS plus growth factors, Cambrex), and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic solution (Invitrogen). Mononuclear cells were plated on plastic 6 well 35 mm diameter plates coated with collagen I (rat tail, BD Biosciences) in complete EC growth medium. Medium was exchanged every 24 hours for the first week in culture, to remove non-adherent cells. Colonies of EPC-derived ECs appeared 7-10 days after the initial isolation. The colonies were trypsinized and 200 cells were plated onto a collagen-coated T25 and labeled passage 1.

The hCB-ECs were grown in T75 flasks using EBM2 basal media supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin, EGM2 Singlequots Kit, and 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (10% complete media). Media was changed every other day until the time of experiment. The hCB-ECs were passaged 1:10 into new T75 flasks upon reaching confluence. Cells were then subsequently split 1:10. The number of population doublings (PDLs) that occurred between each passage was adjusted based upon a 75% attachment rate and calculated according to the formula ln(10)/ln(2)*(4/3) = 4.43 as previously described.57

EC Characterization

hCB-ECs with fewer than 31 population doublings (PDL) have been extensively studied and their function is very similar to vascular ECs.3, 7, 13, 29, 30 The hCB-ECs are positive for the endothelial-specific CD31 and CD34, and negative for CD14, CD45 and CD115 found on monocytes or hematopoietic cells.11 We previously characterized hCB-ECs and found that they also expressed von Willebrand factor and VE-cadherin.3 Following exposure to 15 dyne/cm2 for 24 or 48 hours, hCB-ECs aligned with the direction of flow,3, 7 increased nitric oxide production, and increased mRNA for endothelial cell specific genes sensitive to flow, KLF2, eNOS, cyclo-oxygenase 2, and thrombomodulin.3 The level and organization of actin filaments are similar in hCB-ECs and human aortic ECs (HAECs) as are the associated values of cell stiffness. hCB-ECs with 31 or fewer PDL had high levels of telomerase and low levels of senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining, so we refer to them as “young” ECs.11 hCB-ECs with 44 or more PDL had low levels of telomerase and high levels of senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining compared to hCB-ECs < 31 PDL, so we refer to them as “aged” ECs.11

Synthesis of Variably Compliant Polyacrylamide Gels

Coverslips were prepared as previously described.42, 59, 60 Briefly, square glass coverslips (No. 2, 22 × 22 mm, VWR) were coated with 0.1 N NaOH (Sigma), and allowed to dry. The coverslips were coated with 3-aminopropyl-trimethoxysilane (Sigma), washed in deionized water, and incubated with a coating of a 0.5% solution of glutaraldehyde (Sigma) in phosphate-buffered saline without calcium and magnesium ((PBS), Invitrogen) at room temperature for 30 min. The coverslips were washed with deionized water and allowed to dry.

Polyacrylamide gels with a Young's modulus of 15,000 Pascals were made with 12% acrylamide/0.13% bis-acrylamide ratio in the gel solution mixture.64 The solutions were adjusted to pH 6.0 with 1N HCl (Sigma) and degassed for 30 min to remove oxygen that may inhibit polymerization. 0.5 μm diameter fluorescent beads (Invitrogen) were added to the gel for traction force experiments. Polymerization was initiated by the addition of a 0.1% ammonium persulfate (Bio-Rad) solution in water to the acrylamide mixture. A total of 20 μL of the mixture was pipetted onto an activated coverslip and a circular coverslip (No. 2, 18 mm diameter, VWR) was used to flatten the drop. Polymerization was allowed to occur for 30 min at room temperature. The circular coverslip was removed, and the gel was glutaraldehyde-immobilized31 with 10 μg/mL of fibronectin (Sigma) for two hours at 4 °C. Gels were washed with DI water and stored in DI water in 35mm petri dishes at 4°C. Gels were used for experiments within two weeks.

Traction Force Microscopy

Traction force microscopy was performed as previously described.25-27, 43 Briefly, low or high passage hCB-ECs were seeded at 100,000 cells on 15,000 Pascal polyacrylamide gels embedded with 0.5-μm-diameter fluorescent beads. The cells were allowed to adhere for 24 hours. Cells were imaged with differential interference contrast microscopy and the fluorescent bead field beneath the cell was imaged immediately after with a XD Spinning Disk Confocal Microscope (Andor). A second fluorescent image of the bead field was taken after the cells were removed with 0.025% trypsin/EDTA (Invitrogen). Removal of the cells with trypsin takes less than 5 minutes. Bead displacements were used to compute cellular traction vectors, T, by using a gradient-based digital image correlation technique to map the displacement of fluorescent beads in the gel.27 The displacement map was converted to the stress distribution, using a numerical algorithm based on the integral Boussinesq solution. The root mean square of the force, |F|, was calculated using the individual components of the traction vectors integrated over the cell area,

| (1) |

where T(x,y) = [Tx(x,y), Ty(x,y)] is the continuous field of traction vectors defined at any spatial position (x,y) within the cell.42 Because the cells have negligible acceleration, the sum of forces should equal zero in order to satisfy Newton's first law of motion. In these studies, the sum of the force on the cell was about 0.01pN, far below the reported root mean square force.

For each experiment, at least 5 cells were examined per condition. These traction forces were averaged together to obtain results for a single experiment.

Actin Visualization

For these experiments, each coverslip with a gel was attached to six-well plates with vacuum grease (Corning). ECs were plated on polyacrylamide for these experiments to maintain consistency with traction force measurements, which were performed on gels. hCB-ECs were seeded at 100,000 cells/well on 6-well plates. At 24 hours post plating, cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 30 minutes at room temperature and permeabilized with 1% Triton in PBS for 5 minutes at room temperature. The cells were then incubated with fluorescein phalloidin (1:40, Invitrogen) to stain for F-actin for 1 hour at room temperature. Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) was used to stain for cell nuclei (1:2000). The stains were visualized with a Zeiss 510 Upright Microscope.

Immunofluorescence

hCB-ECs were seeded at 100,000 cells on 15,000 Pa polyacrylamide gels for consistency with traction force measurements which were performed on gels. At 24 hours post plating, cells were fixed and permeabilized for 3 minutes with methanol or fixed with 2% formaldehyde. Samples fixed with formaldehyde were then blocked with PBS/0.02% Tween 20 (Biorad)/3% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) for 1 hour at room temperature. The samples were then incubated with mouse antibody against heparan sulfate proteoglycan, perlecan (1:250 dilution, clone 7E12, Thermo Scientific) or with mouse antibody against heparan sulfate (1:100 dilution, clone 10E4, US Biological) for 1-2 hours at room temperature. This was followed by secondary antibody incubation with goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 546 (1:250 dilution, Invitrogen) or goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (1:250 dilution, Invitrogen) for 1 hour at room temperature. All antibodies were diluted in PBS/1% BSA. The stains were visualized with a Zeiss 510 Upright Microscope. To examine localization of the antibodies, some samples were not permeabilized.

Glycocalyx Thickness and Density Measurements

The heparan sulfate and perlecan core protein components of the glycocalyx and the nucleus were stained as described above. To measure glycocalyx thickness, z-stack images were taken on the Zeiss 510 Upright Confocal Microscope at 63x at 0.33μm intervals. A pinhole of 1 airy unit was used.45 The numerical aperture of the lens was 1.0 and the refractive index of PBS is about 1.33, which resulted in a axial resolution of about 0.7 μm. The measurements of the glycocalyx thickness, either with or without treaments, are all greater than the axial resolution of 0.7 μm. The results we obtained with this method are similar to other established methods to measure the glycocalyx thickness in cultured ECs using fluorescence and optical sectioning.16, 53 The Zeiss LSM Image Browser was used for generation of z-stack images, 3-D reconstructions, and cross-sectional images. With the cross-sectional images, heparan sulfate or perlecan thickness was measured for each individual EC for the region over the center of the cell nucleus. Only cells that were completely in the field of view and whose surface glycocalyx was continuous were included in the data.16 For each condition, at least 2 fields of view were analyzed. Within each field of view, at least 5 cells were analyzed.

To measure the glycocalyx density, images were taken on the Zeiss 510 Upright Confocal Microscope at 63x. Fluorescence intensity of the samples was measured with ImageJ (NIH). An IgG isotype control was used to determine background fluorescence values. For each experiment at a specific condition, at least 5 fields of view were analyzed. In each field of view, there are 4-5 cells.

Quantification of Actin Filaments

Distribution of actin was determined by drawing a line perpendicular to the direction of actin fibers at random locations with ImageJ. This plot profile was saved as a text file and imported into a custom Matlab program to replot the data as a function of the percentage of distance across the cell in the direction perpendicular to the actin fibers. The fiber thickness was calculated by measuring the distance between line scan peaks at 1/3 of the maximum fluorescence intensity.

Modulation of SIRT1

Modulation of SIRT1 activity was performed using an inhibitor, EX-527 (5μmol/L, Sigma) for 6 hours prior to the start of the experiment, or with an activator SRT1720 (0.16μmol/L, Sigma) for 1 hour prior to the start of the experiment.

Modulation of Glycocalyx

Degradation of the glycocalyx was performed with Flavobacterium heparinum heparinase III (Sigma) at 15 mU/mL for 2 hours prior to the start of the experiment.8, 21, 39, 63 Cells were incubated with Angiopoietin-1 (R&D Systems) at 100 ng/mL for 30 minutes prior to the start of the experiment to increase the thickness of the glycocalyx.47

Statistical Analysis

For Figure 1B and 1C, an ANOVA was performed to determine whether cell age significantly affected hCB-EC traction forces. This was followed by a post-hoc Tukey test to determine between the different ages examined. For Figure 3, a two-factor ANOVA was performed to determine the effect of treatment and age on glycocalyx and cell traction force, respectively. For Figure 5A, a 2-factor ANOVA was performed to determine the effect of treatment and age on cell traction force. For Figure 5B, a two-factor ANOVA was performed to determine the effect of treatment and age on junction tension. For Tables 1-3, a two-factor ANOVA for age and treatment was performed to determine the effect of both factors on actin filament thickness or number of fibers per cell width. A post-hoc Tukey test was then performed to determine differences between treatment groups. All statistical analysis was performed in JMP. The value of n represents the number of experiments performed. All data is reported as mean ± S.E.

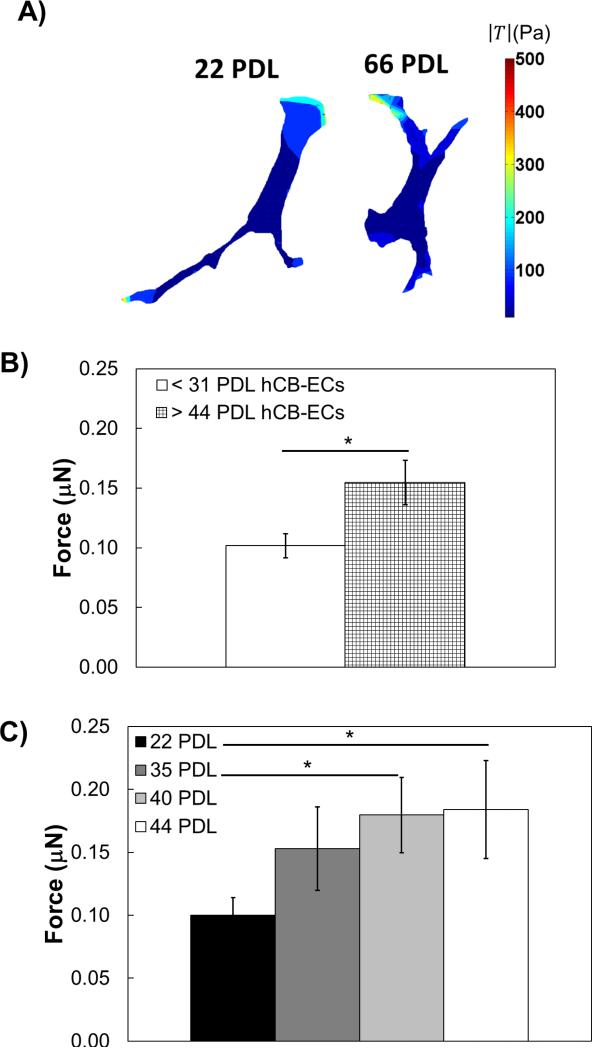

Figure 1.

Aged hCB-ECs exhibit increased traction forces and altered actin localization. A) Representative contour plot of cell traction stresses; B) Aged (> 44 PDL) hCB-ECs have higher total traction force than young (< 31 PDL) hCB-ECs; n=4-5. *p<0.05.C) Traction forces increase with increasing cell age for cells from one isolation. n=4. *:p<0.05.

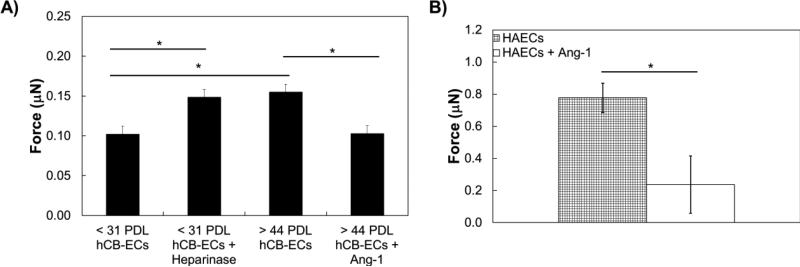

Figure 3.

Traction forces are glycocalyx-dependent. A) Heparinase, which degrades the glycocalyx, significantly increases traction forces in < 31 PDL hCB-ECs. Angipoietin-1, which increases the glycocalyx thickness, significantly decreases traction forces in > 44 PDL hCB-ECs; B) Angiopoietin-1 significantly decreases traction forces in HAECs. n=3-5. *p<0.05.

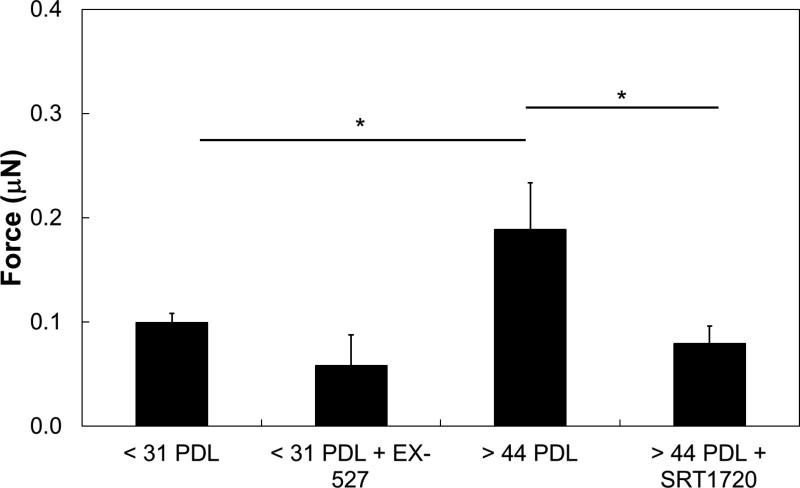

Figure 5.

Effect of SIRT1 on traction forces. For isolated cells, inhibition of SIRT1 in young (< 31 PDL) with 5μM EX-527 has no significant effect on traction forces compared to untreated control. Elevation of SIRT1 in aged (> 44 PDL) with 0.16μM SRT1720 decreases traction forces compared to untreated control n=3-7. *:p<0.05.

Table 1.

Glycocalyx Alters Actin Filament Thickness.

| Condition | Actin filament Thickness (μm) |

|---|---|

| < 31 PDL | 1.1 ± 0.2 |

| < 31 PDL + Heparinase | 1.8 ± 0.1* |

| > 44 PDL | 2.2 ± 0.2# |

| > 44 PDL + Angiopoietin-1 | 1.5 ± 0.1* |

p<0.05 compared to untreated control

p<0.01 compared to < 31 PDL. n=3.

Table 3.

Effect of SIRT1 on Actin Filament Thickness.

| Condition | Actin Filament Thickness (μm) |

|---|---|

| < 31 PDL | 1.4 ± 0.1 |

| < 31 PDL + EX-527 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| > 44 PDL | 1.7 ± 0.1* |

| > 44 PDL + SRT1720 | 1.4 ± 0.1* |

p<0.05 compared to >44 PDL

^p<0.05 compared to < 31 PDL. n=3.

Results

Aged hCB-ECs from Multiple Isolations Exhibit Increased Traction Forces

To determine whether traction forces differed between young and old hCB-ECs, we measured the traction forces for isolated young (< 31 PDL) and aged (> 44 PDL) hCBECs from 3 separate isolations. For these experiments, hCB-ECs of all ages were seeded on 15 kPa gels. In our method, the resolution of the displacement is 0.1 pixel and the resolution of the traction stress is 10Pa. While the distribution pattern of traction stresses are similar for young and old hCB-ECs on 15kPa gels (Figure 1A), aged hCB-ECs exhibited total traction forces that were about 50% higher than young hCB-ECs (Figure 1B, p<0.05). There was no statistically significant effect of EC donor on the traction forces.

Traction Forces Increase with Increasing Cell Age for hCB-ECs from One Isolation

To eliminate any effect of the donor on the traction force results, we examined traction forces with increasing cell age for hCB-ECs from a single isolation and seeded on 15,000 Pa gels. The traction forces significantly increased with increasing cell age (Figure 1C, p<0.05). Older hCB-ECs at 40 PDL and 44 PDL exhibited significantly higher forces than younger hCB-ECs at 22 PDL (p<0.05). These results show that aging of hCB-ECs increases their traction forces for cells from a single isolation.

Modulation of Glycocalyx Alters hCB-EC Traction Forces

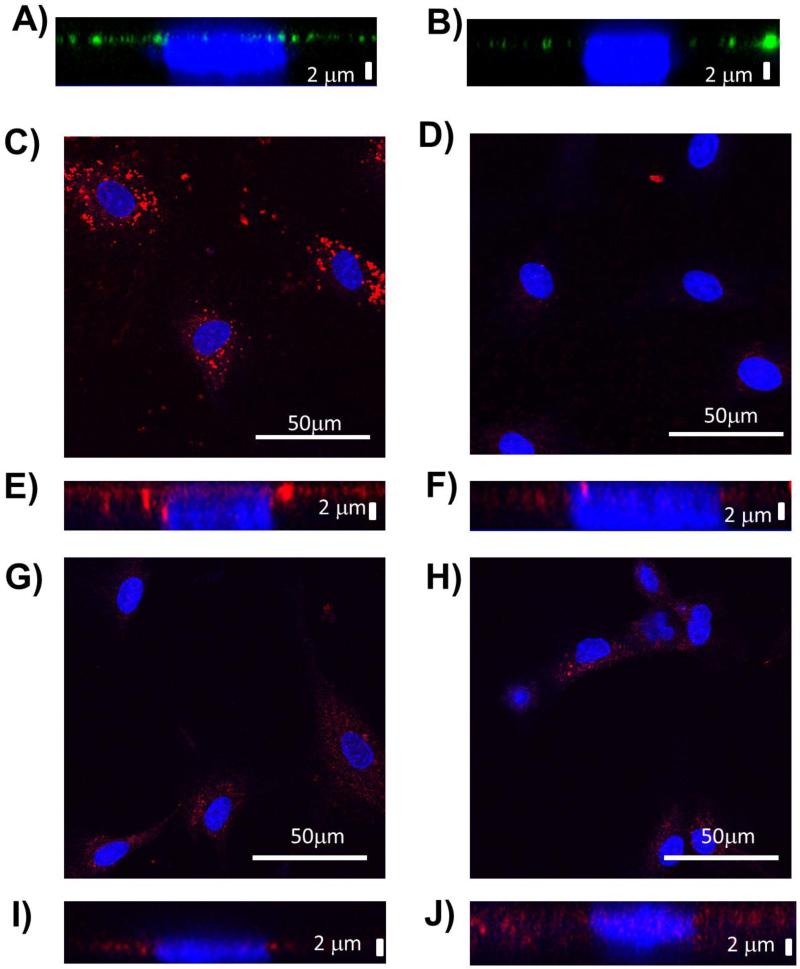

Because the glycocalyx plays an important role in regulation of endothelial mechanotransduction56, we examined whether the glycocalyx differed between young and old cells and whether disruption of the glycocalyx in isolated cells led to elevated traction forces. To examine the glycocalyx, we quantified immunofluorescence for both a heparan sulfate core protein, perlecan, and heparan sulfate. Both of these proteins have been used to measure glycocalyx thickness and density and are secreted onto the endothelial cell surface.16, 22, 23 The glycocalyx thickness was determined from confocal Z-sections. For young cells, a clear band was noticeable in the Z-sections above the nucleus with a thickness of 1.7 ± 0.2 μm for heparan sulfate (Figure 2A) and 2.0 ± 0.4 μm for perlecan (Figure 2E). The difference in layer thickness for the two antibodies was not statistically significant. The perlecan band was located on the luminal surface and the location of the perlecan layer was not affected by permeabilization of the cells, suggesting that the conditions only labeled perlecan in the glycocalyx. Heparan sulfate was significantly thicker (p<0.05) in young hCB-ECs (1.7 ± 0.2 μm, Figure 2A) compared to aged hCB-ECs (1.2 ± 0.1 μm, Figure 2B). Immunofluorescence for the heparan sulfate core protein, perlecan, was visible on the luminal surface of young cells (Figure 2E) and the fluorescence intensity was greatly reduced for older cells (Figure 2I). For both young and old cells, the fluorescence was above background isotype control values

Figure 2.

Representative images of Z-stack images of heparan sulfate layer thickness for A) young hCB-ECs and B) old hCB-ECs. Heparan sulfate core protein perlecan for C) young hCB-ECs and D) young hCB-ECs after treatment with heparinase. Z-stack images of perlecan layer thickness for E) young hCB-ECs and F) young hCB-ECs after treatment with heparinase. Representative images of heparan sulfate core protein perlecan for G) old hCB-ECs and H) old hCB-ECs after treatment with angiopoietin-1. Z-stack images of perlecan layer thickness for I) old hCB-ECs and J) old hCB-ECs after treatment with angiopietin-1.

In older cells, the perlecan layer thickness was 1.6 ± 0.2 μm (Figure 2I), which is a 20% decrease compared to young hCB-ECs (2.0 ± 0.4 μm, Figure 2E) (p<0.05). Perlecan density also decreased noticeably by 47% in aged hCB-ECs (Figure 2G) compared to young (Figure 2C). There was a significant effect of both age (p<0.05) and treatment (p<0.05) on perlecan immunofluorescence.

Heparinase treatment decreased the perlecan density of < 31 PDL hCB-ECs by 21±9% compared to untreated controls (Figures 2C and 2D, p<0.05). Heparinase did not significantly alter glycocalyx thickness which is consistent with previously reported results (Figures 2E and 2F).16 Angiopoietin-1 treatment enhanced the perlecan thickness in > 44 PDL hCB-ECs by 90±11% compared to untreated controls (Figures 2I and 2J, p<0.05), but had no significant effect on perlecan density (Figures 2G and 2H). Angiopoietin-1 has been shown to increase the perlecan thickness by increasing translocation of glycosaminoglycans from the Golgi.47

We then applied these treatments to the cells to determine the effect of the glycocalyx on traction forces. The heparinase treatment increased traction forces in < 31 PDL hCB-ECs by 48% (Figure 3A, p<0.05). Conversely, angiopoietin-1 decreased traction forces in > 44 PDL hCB-ECs by 51% (Figure 3A, p<0.05) compared to untreated controls. HAECs, which have telomerase activity similar to older hCB-ECs (45-71 doublings),11 have substantially greater traction forces (Figure 3B). Treatment with angiopoietin-1 also decreased traction forces in HAECs by 71% (Figure 3B, p<0.05). Taken together, these results show that traction forces are lower for cells with thicker and/or more abundant heparan sulfate or perlecan in the glycocalyx.

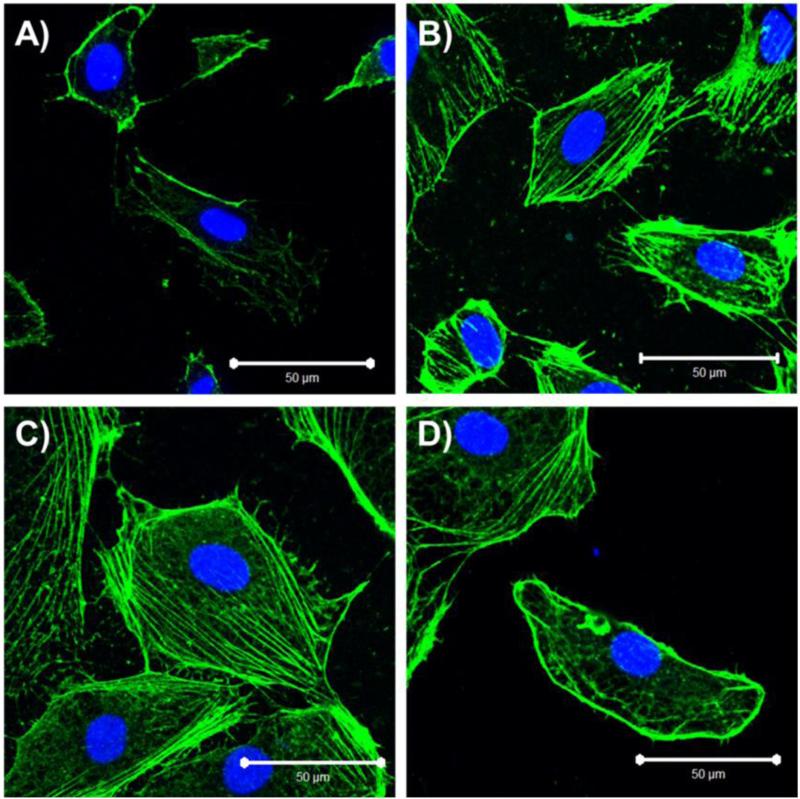

Modulation of Glycocalyx Alters Actin Filament Formation

To determine whether altered traction forces due to disruption of the glycocalyx affect actin size and density, we examined actin filament localization and thickness after treatment with agents known to alter the glycocalyx. In 27 PDL hCB-ECs, actin was localized at the periphery of the cells (Figure 4A). However, in 27 PDL hCB-ECs treated with heparinase to degrade the glycocalyx, there is some formation of actin filaments along the length of the cell (Figure 4B). In 49 PDL hCB-ECs, actin filaments were present throughout the length of the cell (Figure 4C). When these cells were treated with angiopoietin-1 to increases the thickness of the glycocalyx, actin filaments appeared thinner and there was some increase in localization of actin to the periphery of the cell (Figure 4D). We also found that there was a significant effect of both age (p<0.01) and treatment (p<0.05) on actin filament thickness (Table 1). Heparinase led to an increase in actin filament thickness compared to untreated cells (Table 1, p<0.05). Actin fibers in aged hCB-ECs were thicker than in 27 PDL hCB-ECs (Table 1, p<0.01), but became thinner in aged hCB-ECs treated with angiopoietin-1 compared to the untreated control (Table 1, p<0.05). There was a significant effect of age (p<0.05) and treatment (p<0.05) on the number of actin filaments per cell width (Table 2). Treatment of aged hCB-ECs with angiopoietin-1 significantly reduced the number of actin filaments per cell width (Table 2, p<0.05). Taken together, these results show that age-associated changes in the glycocalyx can alter actin filament localization and thickness.

Figure 4.

Actin localization is glycocalyx-dependent. Actin is localized to the cell periphery in A) 22 PDL hCB-ECs, while fibers form along the length of the cell in B) 22 PDL hCB-ECs with heparinase. Actin filaments are present throughout the cell in C) 49 PDL hCB-ECs, while fibers begin to localize to periphery in D) 49 PDL hCB-ECs with angiopioetin-1.

Table 2.

Effect of Agents that Affect SIRT1 or the Glycocalyx on Number of Actin Filaments per Cell Width.

| Condition | Number of F-actin Fibers per Cell Width |

|---|---|

| < 31 PDL | 10.8 ± 0.9 |

| < 31 PDL + EX-527 | 9.7 ± 1.2 |

| < 31 PDL + Heparinase | 12.8 ± 0.9 |

| > 44 PDL | 15.7 ± 2.6^ |

| > 44 PDL + SRT1720 | 10.4 ± 1.3 |

| > 44 PDL + Angiopioetin-1 | 8.3 ± 0.9* |

p<0.05 compared to > 44 PDL

p<0.05 compared to < 31 PDL. n=7-12.

Effect of SIRT1 Treatments on Traction Forces

Because elevating SIRT1 plays an important role in reversal of senescence-associated phenotypes10, 11, 14, 40, 66 and regulation of shear stress-induced eNOS,9 we sought to determine whether modulation of SIRT1 altered cell traction forces. Isolated aged ECs (> 44 PDL) had significantly higher traction forces compared to the untreated young (< 31 PDL) hCB-EC control (Figure 5, p<0.05). Inhibition of SIRT1 in isolated young hCBECs with EX-527 had no significant effect on traction forces compared to the untreated young hCB-EC condition. However, activation of SIRT1 with SRT1720 in aged (> 44 PDL) hCB-ECs did significantly reduce traction forces compared to the untreated aged hCB-EC control (Figure 4, p<0.05).

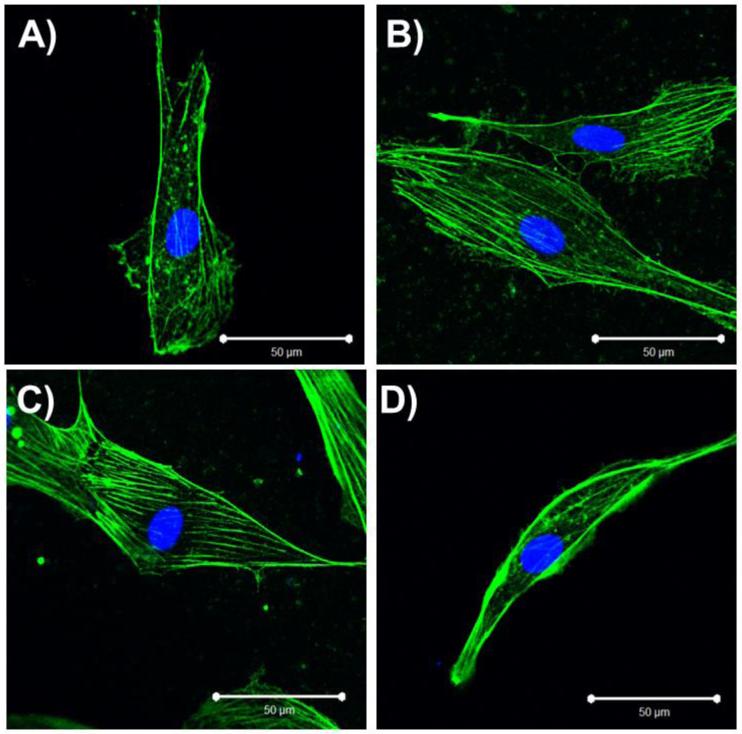

Effect of SIRT1 Treatments on Actin Filaments

Aged (> 44 PDL) hCB-ECs exhibited more actin filaments present throughout the length of the cell (Figure 6C) compared to young (< 31 PDL) hCB-ECs (Figure 6A) (Table 2). Filaments in aged hCB-ECs were also significantly thicker than those in young hCBECs (Table 3, p<0.05). Treatment of young hCB-ECs with EX-527 to inhibit SIRT1 increased the number of filaments present in the cell (Figure 6B) compared to the untreated condition (Figure 6A). There was no statistically significant change in filament thickness after treatment of young hCB-ECs with EX-527 (Table 3). Treatment of aged hCB-ECs with SRT1720 to activate SIRT1 led to increased actin at the periphery of the cells (Figure 6D) compared to the untreated aged hCB-ECs (Figure 6C). Treatment with SRT1720 also significantly decreased actin filament thickness compared to aged hCB-ECs (Table 2, p<0.05). There was a significant effect of age (p<0.05) and treatment (p<0.05) on the number of actin filaments per cell width (Table 3). These results suggest that activating SIRT1 in older cells may affect actin filament formation and localization.

Figure 6.

Effect of SIRT1 on actin filaments. A) Actin filaments localize to periphery in young hCB-ECs; B) Treatment of young hCB-ECs with 5μM EX-527 to inhibit SIRT1 leads to some formation of filaments throughout the length of the cell; C) Aged hCBECs have actin fibers present throughout the length of the cell; D) Aged hCB-ECs with 0.16μM SRT1720 have more actin localization at periphery of the cell.

Discussion

EC cell traction forces are affected by actin localization and actomyosin contractility,12, 28, 41 integrin levels,49 focal adhesion formation,13, 17 and Rho activity.28, 62 Actin binding to vinculin is necessary for cell traction force generation.54 Furthermore, elevated Rho or Rho-associated kinase activity can stimulate cell contractility by modulating actomyosin contraction. In this study, we demonstrated that senescent hCB-ECs exhibited increased traction forces and thicker and more abundant actin filaments due to age-associated changes in the glycocalyx and SIRT1. The traction force increase in senescent hCB-ECs correlated with decreased glycocalyx intensity and thickness as well as increased actin fiber thickness. Altering glycocalyx thickness and density affected actin filament thickness and localization. Likewise, activating SIRT1 in aged EC led to a decrease in actin filament thickness, although direct inhibition of SIRT1 with EX-527 for 6 hours prior to the start of the experiment was not sufficient to elevate traction forces or altering actin fiber thickness in young (< 31 PDL) hCB-ECs.

hCB-ECs were used in this study because of their low, physiological permeability,11 high proliferative potential,11 and similarity to arterial ECs.3 Traction forces for both young and aged hCB-ECs were low compared to those previously reported for BAECs.6, 28 For reference, we found that when attached to polyacrylamide gels with an elastic modulus of 15 kPa, the traction force for human aortic ECs were 0.78±0.09μN, which is close to previously reported values in BAECs.28 This traction force result correlates with the reduced permeability in hCB-ECs compared to HAECs.11 Both hCB-ECs and HAECs exhibited a decline in traction force after exposure to angiopoietin-1.

There is increasing evidence that the method of fibronectin immobilization can affect the interactions of fibronectin with integrins, which can modify cell adhesion to polymer substrates. The method of immobilization may alter adhesion and traction force. As long as the treatments do not have a differential effect upon signaling resulting from integrin engagement, we do not expect the method of immobilization to alter the trends following the various treatments. Further, varying linker density can affect collagen protein tethering on polyacrylamide gels.61 However, stiffness-induced stem cell differentiation was independent of changes to protein tethering or gel porosity.61

The glycocalyx thickness of the aged ECs measured in this study using antibodies to either heparan sulfate or perlecan is comparable to the previously measured value of 1.38±0.07μm in bovine aortic ECs.16 Additionally, we stained for both a heparan sulfate core protein, perlecan, and heparan sulfate. Both stains yielded similar trends with age. Although perlecan is a core protein, it can be secreted into the glycocalyx22 and has been used as to measure glycocalyx thickness.23 Henderson-Toth et al. showed that treatment with heparinase does reduce the abundance of perlecan, which is consistent with our observations.23 Although we did not find a significant effect of heparinase on perlecan thickness, it is possible that a longer exposure of the cells to heparinase could alter the results. This suggests that the heparan sulfate does have a role in anchoring perlecan to the endothelial glycocalyx on the abluminal surface.

Z-stack sections of 0.33 μm were used to visualize the glycocalyx. The resolution of the confocal microscope section images was calculated to be 0.7 μm (refractive index of PBS = 1.33, wavelengths used = 405, 488, and 546 nm, numerical aperture = 1.0),45 which is less than the values of the glycocalyx thickness that we measured in this study. Using antibodies to different components of the glycocalyx, we were able to resolve the glycocalyx (Figure 2). With these values of glycocalyx thickness, we then determined changes in both thickness and density with age. The values of the glycocalyx thickness, either with or without treatment, are greater than the axial resolution of 0.7 μm. An alternative way to visualize the glycocalyx is with cryo-TEM as this eliminates the need for aldehyde fixation or alcohol dehydration. The thickness of bovine aortic EC glycocalyx measured by cryo-TEM was about 11 μm,16 which is significantly thicker than any estimate obtained from confocal imaging or from functional measurements. Cryo-TEM would provide additional insight into the structure and appearance of the glycocalyx, but the trends with age and treatments would remain the same.

There are several other factors that could contribute to elevated traction forces in aging hCB-ECs, including integrin levels and changes in Rho activity. Integrin α5β1 plays an important role in cell force generation through the RhoA-Rock pathway.49 Integrin β4 has been shown to be elevated in a mouse model during aging and atherosclerosis.51 Knockdown of integrin β4 in the mouse attenuated the decrease in endothelial nitric oxide synthase associated with senescent ECs,51 suggesting that the integrins may play an important role in aging EC mechanotransduction.

Interaction between integrins and the extracellular matrix can lead to clustering and the formation of focal adhesions.1, 2, 19, 46 Focal adhesions mediate force transmission between integrins and the actin cytoskeleton.13, 18 Vinculin, a focal adhesion protein, has been demonstrated to be important in regulating myosin contractility dependent adhesions and traction forces.15 Senescent human umbilical vein ECs have inhibited migration due to an increased amount of focal adhesion sites.20 Therefore, it is possible that changes in the amount of focal adhesions in senescent ECs play a role in altering cell traction forces.

Rho GTPases have also been shown to be important in mediating cell contractility and cell traction forces. In human umbilical vein ECs, inhibition of RhoA and Rac1 decreased permeability, cell contractility, and assembly of actin filaments.62 Dominant-negative Cdc42 reduced actin filament formation and contractility, but did not alter permeability.62 In bovine aortic ECs, increases in traction force and permeability on stiff substrates was attributed to increased activation of RhoA.28 When the downstream effector Rho-dependent kinase was inhibited, there was a reduction in monolayer permeability and cell traction force.28

To fully understand the role of endothelial cell force generation in atherosclerosis development, the effect of shear stress and intracellular forces would have to be considered. After exposure to flow for 16 hours, the traction force for confluent ECs was slightly greater for cells exposed to steady shear stress than for cells under static conditions or cells exposed to recirculating flow.55 Steady flow also caused the surface traction force vectors to align in the direction of flow and increased intracellular forces.55 Static conditions or recirculating flow did not alter alignment of surface traction forces.55 Interestingly, the tension induced by shear stress was significantly less than the intracellular tension,55 suggesting that while changes to the intracellular tension are initiated by shear stress, the magnitude of the intracellular tension reflects both biochemical changes within the cell as well as cell-cell and cell-substrate interactions.

Under shear stress, the glycocalyx is necessary for rearrangement of the cytoskeleton and alignment in the direction of flow for ECs.65 Our results for cells under static conditions on soft substrates also show a relationship between the cytoskeleton and glycocalyx. Modulation of the glycocalyx with heparinase or angiopoietin-1 altered both cell traction forces and actin localization and fiber thickness. There was also an age-related decline in glycocalyx thickness and density, suggesting that cell senescence can alter the mechanosensing ability of the actin cytoskeleton.

In summary, we showed that senescence of isolated hCB-ECs increases traction forces. Furthermore, traction forces can be modulated by altering the glycocalyx or SIRT1 in an age-associated manner. Changes in actin localization and actin filament thickness also correlated with changes in aging hCB-EC traction forces.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a NSF Graduate Research Fellowship (T.M.C.), a McChesney Graduate Fellowship (T.M.C.), an Undergraduate Research Support Assistantship (J.B.Y.), and a Pratt Research Fellowship (J.J.F.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Tracy M. Cheung, Jessica B. Yan, Justin J. Fu, Jianyong Huang, Fan Yuan, and George A. Truskey declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standards

No human or animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

References

- 1.Balaban NQ, Schwarz US, Riveline D, Goichberg P, Tzur G, Sabanay I, Mahalu D, Safran S, Bershadsky A, Addadi L, Geiger B. Force and focal adhesion assembly: A close relationship studied using elastic micropatterned substrates. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(5):466–72. doi: 10.1038/35074532. doi: http://www.nature.com/ncb/journal/v3/n5/suppinfo/ncb0501_466_S1.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beningo KA, Dembo M, Kaverina I, Small JV, Wang Y.-l. Nascent focal adhesions are responsible for the generation of strong propulsive forces in migrating fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 2001;153(4):881–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.881. doi:10.1083/jcb.153.4.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown MA, Wallace CS, Angelos M, Truskey GA. Characterization of umbilical cord blood-derived late outgrowth endothelial progenitor cells exposed to laminar shear stress. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15(11):3575–87. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0444. doi:10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burrig K. The endothelium of advanced arteriosclerotic plaques in humans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1991;11(6):1678–89. doi:10.1161/01.atv.11.6.1678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai H. Hydrogen peroxide regulation of endothelial function: Origins, mechanisms, and consequences. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68(1):26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.06.021. doi:10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Califano J, Reinhart-King C. Substrate stiffness and cell area predict cellular traction stresses in single cells and cells in contact. Cel Mol Bioeng. 2010;3(1):68–75. doi: 10.1007/s12195-010-0102-6. doi:10.1007/s12195-010-0102-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao L, Wu A, Truskey GA. Biomechanical effects of flow and coculture on human aortic and cord blood-derived endothelial cells. J Biomech. 2011;44(11):2150–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chappell D, Jacob M, Rehm M, Stoeckelhuber M, Welsch U, Conzen P, Becker BF. Heparinase selectively sheds heparan sulfate from the endothelial glycocalyx. Biological Chemistry. 2007;389(1):79–82. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Z, Peng I-C, Cui X, Li Y-S, Chien S, Shyy JY-J. Shear stress, sirt1, and vascular homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sc. 2010;107(22):10268–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003833107. doi:10.1073/pnas.1003833107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheung T, Ganatra M, Fu J, Truskey G. The effect of stress-induced senescence on aging human cord blood-derived endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Eng Tech. 2013;4(2):220–30. doi: 10.1007/s13239-013-0128-8. doi:10.1007/s13239-013-0128-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheung TM, Ganatra MP, Peters EB, Truskey GA. The effect of cellular senescence on the albumin permeability of blood-derived endothelial cells. Am J Physiol -Heart C. 2012;303(11):H1374–H83. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00182.2012. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00182.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chi Q, Yin T, Gregersen H, Deng X, Fan Y, Zhao J, Liao D, Wang G. Rear actomyosin contractility-driven directional cell migration in three-dimensional matrices: A mechano-chemical coupling mechanism. Journal of The Royal Society Interface. 11(95):2014. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2013.1072. doi:10.1098/rsif.2013.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choquet D, Felsenfeld DP, Sheetz MP. Extracellular matrix rigidity causes strengthening of integrin–cytoskeleton linkages. Cell. 1997;88(1):39–48. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81856-5. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81856-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cullere X, Shaw SK, Andersson L, Hirahashi J, Luscinskas FW, Mayadas TN. Regulation of vascular endothelial barrier function by epac, a camp-activated exchange factor for rap gtpase. Blood. 2005;105(5):1950–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1987. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-05-1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dumbauld DW, Lee TT, Singh A, Scrimgeour J, Gersbach CA, Zamir EA, Fu J, Chen CS, Curtis JE, Craig SW, García AJ. How vinculin regulates force transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sc. 2013;110(24):9788–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216209110. doi:10.1073/pnas.1216209110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ebong EE, Macaluso FP, Spray DC, Tarbell JM. Imaging the endothelial glycocalyx in vitro by rapid freezing/freeze substitution transmission electron microscopy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(8):1908–15. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.225268. doi:10.1161/atvbaha.111.225268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erusalimsky JD, Skene C. Mechanisms of endothelial senescence. Exp Physiol. 2009;94(3):299–304. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.043133. doi:10.1113/expphysiol.2008.043133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galbraith CG, Yamada KM, Sheetz MP. The relationship between force and focal complex development. J Cell Biol. 2002;159(4):695–705. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200204153. doi:10.1083/jcb.200204153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallant ND, Michael KE, García AJ. Cell adhesion strengthening: Contributions of adhesive area, integrin binding, and focal adhesion assembly. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(9):4329–40. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-02-0170. doi:10.1091/mbc.E05-02-0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garfinkel S, Hu X, Prudovsky IA, McMahon GA, Kapnik EM, McDowell SD, Maciag T. Fgf-1-dependent proliferative and migratory responses are impaired in senescent human umbilical vein endothelial cells and correlate with the inability to signal tyrosine phosphorylation of fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 substrates. J Cell Biol. 1996;134(3):783–91. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.3.783. doi:10.1083/jcb.134.3.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giantsos-Adams K, Koo A-A, Song S, Sakai J, Sankaran J, Shin J, Garcia-Cardena G, Dewey CF., Jr. Heparan sulfate regrowth profiles under laminar shear flow following enzymatic degradation. Cel Mol Bioeng. 2013;6(2):160–74. doi: 10.1007/s12195-013-0273-z. doi:10.1007/s12195-013-0273-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haraldsson B, Nyström J, Deen WM. Properties of the glomerular barrier and mechanisms of proteinuria. Physiol Rev. 2008;88(2):451–87. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00055.2006. doi:10.1152/physrev.00055.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henderson-Toth CE, Jahnsen ED, Jamarani R, Al-Roubaie S, Jones EAV. The glycocalyx is present as soon as blood flow is initiated and is required for normal vascular development. Dev Biol. 2012;369(2):330–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.07.009. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herrmann RA, Malinauskas RA, Truskey GA. Characterization of sites of elevated low density lipoprotein at the intercostal, celiac, and iliac branches of the rabbit aorta. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1994;14(313–323) doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang J, Deng H, Peng X, Li S, Xiong C, Fang J. Cellular traction force reconstruction based on a self-adaptive filtering scheme. Cel Mol Bioeng. 2012;5(2):205–16. doi:10.1007/s12195-012-0224-0. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang J, Peng X, Qin L, Zhu T, Xiong C, Zhang Y, Fang J. Determination of cellular tractions on elastic substrate based on an integral boussinesq solution. J Biomech Eng. 2009;131(6):061009. doi: 10.1115/1.3118767. doi:10.1115/1.3118767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang J, Zhu T, Pan X, Qin L, Peng X, Xiong C, Fang J. A high-efficiency digital image correlation method based on a fast recursive scheme. Meas Sci Technol. 2010;21:025101. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huynh J, Nishimura N, Rana K, Peloquin JM, Califano JP, Montague CR, King MR, Schaffer CB, Reinhart-King CA. Age-related intimal stiffening enhances endothelial permeability and leukocyte transmigration. Science Translational Medicine. 2011;3(112):112ra22. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002761. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3002761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ingram DA, Mead LE, Moore DB, Woodard W, Fenoglio A, Yoder MC. Vessel wall-derived endothelial cells rapidly proliferate because they contain a complete hierarchy of endothelial progenitor cells. Blood. 2005;105(7):2783–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3057. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-08-3057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ingram DA, Mead LE, Tanaka H, Meade V, Fenoglio A, Mortell K, Pollok K, Ferkowicz MJ, Gilley D, Yoder MC. Identification of a novel hierarchy of endothelial progenitor cells using human peripheral and umbilical cord blood. Blood. 2004;104(9):2752–60. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuddannaya S, Chuah YJ, Lee MHA, Menon NV, Kang Y, Zhang Y. Surface chemical modification of poly(dimethylsiloxane) for the enhanced adhesion and proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2013;5(19):9777–84. doi: 10.1021/am402903e. doi:10.1021/am402903e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lam CRI, Tan C, Teo Z, Tay CY, Phua T, Wu YL, Cai PQ, Tan LP, Chen X, Zhu P, Tan NS. Loss of tak1 increases cell traction force in a ros-dependent manner to drive epithelial-mesenchymal transition of cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e848. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.339. doi:10.1038/cddis.2013.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marechal X, Favory R, Joulin O, Montaigne D, Hassoun S, Decoster B, Zerimech F, Neviere R. Endothelial glycocalyx damage during endotoxemia coincides with microcirculatory dysfunction and vascular oxidative stress. Shock. 2008;29(5):572–6. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318157e926. 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318157e926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minamino T, Miyauchi H, Yoshida T, Ishida Y, Yoshida H, Komuro I. Endothelial cell senescence in human atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1541–4. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013836.85741.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moldovan L, Mythreye K, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Satterwhite LL. Reactive oxygen species in vascular endothelial cell motility. Roles of nad(p)h oxidase and rac1. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71(2):236–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.05.003. doi:10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nielsen LB, Nordestgaard BG, Stender S, Kjeldsen K. Aortic permeability to ldl as a predictor of aortic cholesterol accumulation in cholesterol-fed rabbits. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1992;12:1402–9. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.12.12.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogami M, Ikura Y, Ohsawa M, Matsuo T, Kayo S, Yoshimi N, Hai E, Shirai N, Ehara S, Komatsu R, Naruko T, Ueda M. Telomere shortening in human coronary artery diseases. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:546–50. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000117200.46938.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okayama N, Kevil CG, Correia L, Jourd'Heuil D, Itoh M, Grisham MB, Alexander JS. Nitric oxide enhances hydrogen peroxide-mediated endothelial permeability in vitro. Am J Physiol-Cell Ph. 1997;273(5):C1581–C7. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.5.C1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pahakis MY, Kosky JR, Dull RO, Tarbell JM. The role of endothelial glycocalyx components in mechanotransduction of fluid shear stress. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2007;355(1):228–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.137. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park S-J, Ahmad F, Philp A, Baar K, Williams T, Luo H, Ke H, Rehmann H, Taussig R, Brown Alexandra L., Kim Myung K., Beaven Michael A., Burgin Alex B., Manganiello V, Chung Jay H. Resveratrol ameliorates aging-related metabolic phenotypes by inhibiting camp phosphodiesterases. Cell. 2012;148(3):421–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.017. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pollard T, Earnshaw W, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Cell biology. Elsevier, Inc.; Philadelphia, PA, USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reinhart-King CA, Dembo M, Hammer DA. The dynamics and mechanics of endothelial cell spreading. Biophys J. 2005;89(1):676–89. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.054320. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1529/biophysj.104.054320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reinhart-King CA, Dembo M, Hammer DA. Endothelial cell traction forces on rgd-derivatized polyacrylamide substrata. Langmuir. 2002;19(5):1573–9. doi:10.1021/la026142j. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reitsma S, Slaaf D, Vink H, van Zandvoort MMJ, oude Egbrink MA. The endothelial glycocalyx: Composition, functions, and visualization. Pflugers Arch -Eur J Physiol. 2007;454(3):345–59. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0212-8. doi:10.1007/s00424-007-0212-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Resolution in a confocal system. http://microscopy.berkeley.edu/courses/TLM/clsm/resolution.html.

- 46.Riveline D, Zamir E, Balaban NQ, Schwarz US, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S, Kam Z, Geiger B, Bershadsky AD. Focal contacts as mechanosensors: Externally applied local mechanical force induces growth of focal contacts by an mdia1-dependent and rock-independent mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2001;153(6):1175–86. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1175. doi:10.1083/jcb.153.6.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salmon AHJ, Neal CR, Sage LM, Glass CA, Harper SJ, Bates DO. Angiopoietin-1 alters microvascular permeability coefficients in vivo via modification of endothelial glycocalyx. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;83(1):24–33. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp093. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvp093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salmon AHJ, Satchell SC. Endothelial glycocalyx dysfunction in disease: Albuminuria and increased microvascular permeability. J Pathol. 2012;226(4):562–74. doi: 10.1002/path.3964. doi:10.1002/path.3964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schiller HB, Hermann M-R, Polleux J, Vignaud T, Zanivan S, Friedel CC, Sun Z, Raducanu A, Gottschalk K-E, Théry M, Mann M, Fässler R. Β1-and αv-class integrins cooperate to regulate myosin ii during rigidity sensing of fibronectin-based microenvironments. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(6):625–36. doi: 10.1038/ncb2747. doi:10.1038/ncb2747 http://www.nature.com/ncb/journal/v15/n6/abs/ncb2747.html#supplementary-information. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silacci P, Desgeorges A, Mazzolai L, Chambaz C, Hayoz D. Flow pulsatility is a critical determinant of oxidative stress in endothelial cells. Hypertension. 2001;38(5):1162–6. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.095993. doi:10.1161/hy1101.095993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun C, Liu X, Qi L, Xu J, Zhao J, Zhang Y, Zhang S, Miao J. Modulation of vascular endothelial cell senescence by integrin β4. J Cell Physiol. 2010;225(3):673–81. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22262. doi:10.1002/jcp.22262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tarbell JM. Shear stress and the endothelial transport barrier. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87(2):320–30. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq146. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvq146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thi MM, Tarbell JM, Weinbaum S, Spray DC. The role of the glycocalyx in reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton under fluid shear stress: A “bumper-car” model. Proc Natl Acad Sc. 2004;101(47):16483–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407474101. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407474101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thompson Peter M., Tolbert Caitlin E., Shen K, Kota P, Palmer Sean M., Plevock Karen M., Orlova A, Galkin Vitold E., Burridge K, Egelman Edward H., Dokholyan Nikolay V., Superfine R, Campbell Sharon L. Identification of an actin binding surface on vinculin that mediates mechanical cell and focal adhesion properties. Structure. 2014;22(5):697–706. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.03.002. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.str.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ting L, Jessica J, Jahn R, Jung J, Shuman B, Feghhi S, Han S, Rodriguez M, Sniadecki N. Flow mechanotransduction regulates traction forces, intercellular forces, and adherens junctions. Am J Physiol. 2012;302:H2220–H9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00975.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van den Berg BM, Spaan JAE, Rolf TM, Vink H. Atherogenic region and diet diminish glycocalyx dimension and increase intima-to-media ratios at murine carotid artery bifurcation. Am J Physiol -Heart C. 2006;290(2):H915–H20. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00051.2005. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00051.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van der Loo B, Fenton MJ, Erusalimsky JD. Cytochemical detection of a senescence-associated β-galactosidase in endothelial and smooth muscle cells from human and rabbit blood vessels. Exp Cell Res. 1998;241(2):309–15. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4035. doi:10.1006/excr.1998.4035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Popele NM, Grobbee DE, Bots ML, Asmar R, Topouchian J, Reneman RS, Hoeks APG, van der Kuip DAM, Hofman A, Witteman JCM. Association between arterial stiffness and atherosclerosis: The rotterdam study. Stroke. 2001;32(2):454–60. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.2.454. doi:10.1161/01.str.32.2.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wallace CS, Strike SA, Truskey GA. Smooth muscle cell rigidity and extracellular matrix organization influence endothelial cell spreading and adhesion formation in coculture. Am J Physiol-Cell Ph. 2007;293(3):H1978–H86. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00618.2007. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00618.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Y-L, Pelham RJ., Jr Preparation of a flexible, porous polyacrylamide substrate for mechanical studies of cultured cells. Methods in Enzymology. 1998;298:489–96. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)98041-7. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0076-6879(98)98041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wen JH, Vincent LG, Fuhrmann A, Choi YS, Hribar KC, Taylor-Weiner H, Chen S, Engler AJ. Interplay of matrix stiffness and protein tethering in stem cell differentiation. Nat Mater. 2014;13(10):979–87. doi: 10.1038/nmat4051. doi:10.1038/nmat4051 http://www.nature.com/nmat/journal/v13/n10/abs/nmat4051.html#supplementary-information. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wojciak-Stothard B, Potempa S, Eichholtz T, Ridley AJ. 9rgr; and rac but not cdc42 regulate endothelial cell permeability. J Cell Science. 2001;114(7):1343–55. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.7.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yao Y, Rabodzey A, Dewey CF. Glycocalyx modulates the motility and proliferative response of vascular endothelium to fluid shear stress. Am J Physiol -Heart C. 2007;293(2):H1023–H30. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00162.2007. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00162.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yeung T, Georges PC, Flanagan LA, Marg B, Ortiz M, Funaki M, Zahir N, Ming W, Weaver V, Janmey PA. Effects of substrate stiffness on cell morphology, cytoskeletal structure, and adhesion. Cell Motility and the Cytoskeleton. 2005;60(1):24–34. doi: 10.1002/cm.20041. doi:10.1002/cm.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zeng Y, Tarbell JM. The adaptive remodeling of endothelial glycocalyx in response to fluid shear stress. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e86249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086249. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0086249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zu Y, Liu L, Lee MYK, Xu C, Liang Y, Man RY, Vanhoutte PM, Wang Y. Sirt1 promotes proliferation and prevents senescence through targeting lkb1 in primary porcine aortic endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2010;106(8):1384–93. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.215483. doi:10.1161/circresaha.109.215483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]