Abstract

Background

Numerous, often multi-faceted regimens are available for treating complex wounds, yet the evidence of these interventions is recondite across the literature. We aimed to identify effective interventions to treat complex wounds through an overview of systematic reviews.

Methods

MEDLINE (OVID interface, 1946 until October 26, 2012), EMBASE (OVID interface, 1947 until October 26, 2012), and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Issue 10 of 12, 2012) were searched on October 26, 2012. Systematic reviews that examined adults receiving care for their complex wounds were included. Two reviewers independently screened the literature, abstracted data, and assessed study quality using the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) tool.

Results

Overall, 99 systematic reviews were included after screening 6,200 titles and abstracts and 422 full-texts; 54 were systematic reviews with a meta-analysis (including data on over 54,000 patients) and 45 were systematic reviews without a meta-analysis. Overall, 44% of included reviews were rated as being of high quality (AMSTAR score ≥8). Based on data from systematic reviews including a meta-analysis with an AMSTAR score ≥8, promising interventions for complex wounds were identified. These included bandages or stockings (multi-layer, high compression) and wound cleansing for venous leg ulcers; four-layer bandages for mixed arterial/venous leg ulcers; biologics, ultrasound, and hydrogel dressings for diabetic leg/foot ulcers; hydrocolloid dressings, electrotherapy, air-fluidized beds, and alternate foam mattresses for pressure ulcers; and silver dressings and ultrasound for unspecified mixed complex wounds. For surgical wound infections, topical negative pressure and vacuum-assisted closure were promising interventions, but this was based on evidence from moderate to low quality systematic reviews.

Conclusions

Numerous interventions can be utilized for patients with varying types of complex wounds, yet few treatments were consistently effective across all outcomes throughout the literature. Clinicians and patients can use our results to tailor effective treatment according to type of complex wound. Network meta-analysis will be of benefit to decision-makers, as it will permit multiple treatment comparisons and ranking of the effectiveness of all interventions.

Please see related article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0326-3

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0288-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Complex wound, Effectiveness, Systematic review, Treatment, Ulcer, Wounds

Background

Chronic wounds are those that have not progressed through the ordered process of healing to yield a functional result [1]. Recently, the terminology for chronic wounds has changed. The preferred term to refer to a chronic wound is a “complex wound” [2]. One of the following characteristics is necessary for a wound to be classified as being complex: i) has not healed in 3 months, ii) infection is present, iii) compromised viability of superficial tissues, necrosis, or circulation impairment, and iv) association with systemic pathologies, impairing normal healing [2]. The main types of complex wounds include diabetic leg/foot ulcers, pressure ulcers [3], chronic venous ulcers, infected wounds [1,4,5], and those related to vasculitis and immunosuppressive therapy that have not healed using simple care [2].

Complex wounds are a significant burden on society. It has been estimated that complex wounds cost the healthcare system $10 billion annually in North America alone [6]. These estimates often fail to capture indirect costs, including patient/caregiver frustration, economic loss, and decreased quality of life.

Healthcare providers and patients have numerous regimens available for treating wounds [7], including dressings, wound cleansing agents, skin replacement therapy, biologic agents, stockings, nutritional supplementation, complementary and alternative medicine, bandages, and surgery, to name a few. Furthermore, wound care is often multi-faceted, and several interventions may be used concurrently. Some of these interventions have been examined in overviews of Cochrane reviews [8,9]. As the evidence of these interventions is recondite across the literature, we sought to elucidate optimal treatment strategies for complex wounds through an overview of all available systematic reviews, including Cochrane reviews and non-Cochrane reviews.

Methods

Protocol

A protocol for our overview of reviews was developed using the Cochrane Handbook for overviews of reviews [10]. The draft protocol was circulated for feedback from systematic review methodologists, policy-makers, and clinicians with expertise in wound care. It was revised as necessary and the final version is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Eligibility criteria

We included systematic reviews that focused on interventions to treat complex wounds (including venous and arterial ulcers due to chronic illness, diabetic ulcers, pressure ulcers, and infected surgical wounds) amongst adults aged 18 years and older. We used the definition for a systematic review put forth by the Cochrane Collaboration, “A systematic review attempts to collate all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria in order to answer a specific research question. It uses explicit, systematic methods that are selected with a view to minimizing bias, thus providing more reliable findings from which conclusions can be drawn and decisions made” [10].

A list of the 14 different intervention categories can be found in Additional file 1. All comparators, such as other wound care interventions, no treatment, placebo, and usual care were eligible for inclusion. To be included, a systematic review also had to report on our outcomes of interest as identified by decision-makers, including healing (e.g., number of ulcers healed, improvement of ulcers, and time to ulcer healing) or admission to hospital (including readmissions). Systematic reviews that were published or unpublished and conducted at any point in time were included. Due to resource limitations, only systematic reviews written in English were included. However, authors were contacted to obtain translations of reviews written in languages other than English.

Literature search

Comprehensive literature searches were conducted from inception until October 2012 across MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The search terms included both medical subject headings (MeSH) and free text terms related to wound care interventions. Literature searches were conducted by an experienced librarian (LP) on October 26, 2012. Using validated search filters, the search strategies were limited to human participants, adults, and systematic reviews. The electronic database search was supplemented by searching for systematic review protocols in the PROSPERO database [11], contacting authors of conference proceeding abstracts for their unpublished data, and scanning the reference lists of the included systematic reviews.

The search strategy was peer reviewed by another expert librarian on our team (EC) using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies checklist [12] and amended, as necessary. The final search strategy for the MEDLINE database is presented in Additional file 2. The literature search was limited to adults, reviews, and economic studies. The latter limitation was employed to identify cost-effectiveness analyses for a second paper that examines the cost-effectiveness of complex wounds [Tricco et al., unpublished paper submitted to BMC Medicine]. The MEDLINE search was modified for the other two databases, as necessary. Search strategies for the EMBASE and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews are available from the corresponding author, upon request.

Screening

Prior to commencing the screening process, a calibration exercise was conducted to ensure reliability in correctly selecting articles for inclusion. This exercise entailed screening a random sample of 50 of the included titles and abstracts by all team members, independently. The eligibility criteria were modified, as necessary, to optimize clarity. Subsequently, reviewer pairs (ACT, JA, AH, AV, PAK, CW, EC, LP) independently screened the remainder of the search results for inclusion using a pre-defined relevance criteria form for all levels of screening (e.g., title and abstract, full-text review of potentially relevant articles). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion or the involvement of a third reviewer.

Data items

Data abstraction forms were pilot-tested by all team members independently on a random sample of five articles. The data abstraction forms were revised after this exercise, as necessary. Subsequently, reviewer pairs (ACT, JA, AH, AV, PAK, CW, LP, WH) independently read each article and abstracted relevant data. Differences in abstraction were resolved by discussion or the involvement of a third reviewer. Data items included study characteristics (e.g., number of studies identified, type of study designs included, interventions and comparators examined), patient characteristics (e.g., clinical population, wound types, age category), and outcome results (e.g., healing, hospitalizations).

Methodological quality appraisal

The methodological quality of the included systematic reviews were appraised using the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) tool [13]. The reliability and validity of this tool has been established [14]. Items include the use of a protocol, study selection by two reviewers, comprehensive literature search, inclusion of unpublished material, list of included and excluded studies, reporting of study characteristics, quality appraisal, appropriate pooling of data methods, assessment of publication bias, and statement of conflicts of interest. Each included systematic review was appraised by two team members (ACT, JA, AH, AV, PAK, CW, EC, LP) and conflicts were resolved by discussion or the involvement of a third reviewer.

Synthesis

Literature search results and the abstracted data were summarized descriptively. An in-depth comparison of included systematic reviews was compiled and depicted in tables and figures. Conclusion statements for systematic reviews without a meta-analysis were categorized by two reviewers (ACT, JA, AH, AV, PAK, CW, LP, WH), independently, using a pre-existing framework, as follows: positive (authors stated that there is evidence of effectiveness); neutral (no evidence of effectiveness or they reported no opinion); negative (authors advised against the use of the intervention or it was not recommended); or indeterminate (authors stated that there is insufficient evidence or that more research is required) [15]. Conflicts were resolved through discussion and a third reviewer (ACT) verified the categorizations to ensure accuracy.

Results

Literature search

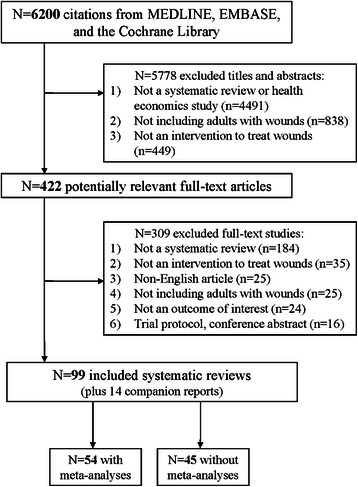

The literature search resulted in 6,200 titles and abstracts, of which 5,778 were excluded for not fulfilling the eligibility criteria (Figure 1). Of the 422 full-texts retrieved and screened in duplicate, 309 articles were excluded. Ninety-nine systematic reviews of wound care interventions were included in this overview of systematic reviews; 54 were systematic reviews with meta-analysis results [16-67] and 45 were systematic reviews without a meta-analysis [68-112]. In addition, 14 companion reports were included [21,113-125], the majority of which were Cochrane updates.

Figure 1.

Study flow. Details the flow of information through the different phases of the review. The flow maps out the number of records identified, included and excluded, and the reasons for their exclusion.

Systematic review characteristics

The reviews were conducted between 1997 and 2012, with 28% taking place after 2011 (Table 1; Additional file 3). The first authors of the systematic reviews were predominantly based in Europe (66%), North America (19%), and Australia or New Zealand (7%). The number of studies included in each review ranged from 0 to 130, with 80% including between 2 and 30 studies. Ninety-three systematic reviews included randomized clinical trials. Five systematic reviews were unpublished [43,58,83,104,106].

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of included systematic reviews

| Characteristic | Number of systematic reviews (n = 99) | Percentage of systematic reviews |

|---|---|---|

| Year | ||

| 1997–1999 | 6 | 6.1 |

| 2000–2002 | 9 | 9.1 |

| 2003–2005 | 15 | 15.2 |

| 2006–2008 | 21 | 21.2 |

| 2009–2011 | 36 | 36.4 |

| 2012 | 12 | 12.1 |

| Country of conduct | ||

| Europe (38 of these are from the United Kingdom) | 65 | 65.7 |

| North America | 19 | 19.2 |

| Australasia (Australia, New Zealand) | 7 | 7.1 |

| Asia (Malaysia, China, Taiwan, India) | 6 | 6.1 |

| South America | 2 | 2.0 |

| Number of studies included | ||

| 0–1 | 3 | 3.0 |

| 2–10 | 53 | 53.5 |

| 11–20 | 16 | 16.2 |

| 21–30 | 10 | 10.1 |

| 31–40 | 6 | 6.1 |

| 41–100 | 8 | 8.1 |

| >100 | 3 | 3.0 |

| Study designs included * | ||

| Randomized clinical trials | 93 | 70.5 |

| Observational studies | ||

| Non-randomized clinical trials | 20 | 15.2 |

| Controlled before-after studies, interrupted | 17 | 12.9 |

| Time series | 2 | 1.5 |

| Patient population | ||

| Not specifically reported | 65 | 65.7 |

| Diabetes | 21 | 21.2 |

| Chronic venous disease | 4 | 4.0 |

| Complex lower limb wounds | 4 | 4.0 |

| Inpatients/institutionalized | 3 | 3.0 |

| Ambulatory patients | 1 | 1.0 |

| Elderly | 1 | 1.0 |

| Type of wound * | ||

| Venous leg ulcers | 36 | 31.3 |

| Diabetic foot/leg ulcers | 26 | 22.6 |

| Pressure ulcers | 20 | 17.4 |

| Mixed arterial/venous leg ulcers | 16 | 13.9 |

| Mixed complex wound unspecified | 10 | 8.7 |

| Infected surgical wounds | 7 | 7.0 |

| Interventions examined * | ||

| Adjuvant | 33 | 20.3 |

| Dressings | 26 | 16.0 |

| Biologics | 16 | 9.8 |

| Other topical | 14 | 8.6 |

| Other oral | 11 | 6.8 |

| Stockings | 10 | 6.1 |

| Support surfaces | 10 | 6.1 |

| Wound cleansing | 10 | 6.1 |

| Skin replacement | 9 | 5.5 |

| Bandages | 7 | 4.3 |

| Surgery | 7 | 4.3 |

| Nutritional supplementation | 4 | 2.5 |

| Wound care program | 4 | 2.5 |

| Complementary and alternative medicine | 2 | 1.2 |

| Comparators examined * | ||

| Usual care | 63 | 45.7 |

| Dressings | 34 | 24.6 |

| Bandages | 8 | 5.8 |

| Not reported | 8 | 5.8 |

| Support surfaces | 7 | 5.1 |

| Other topical | 5 | 3.6 |

| Wound cleansing | 5 | 3.6 |

| Stockings | 4 | 2.9 |

| Other oral | 2 | 1.5 |

| All other treatments | 1 | 0.7 |

| Skin replacement | 1 | 0.7 |

| Number of treatment comparisons per outcome | ||

| Systematic reviews with a meta-analysis | n = 143 comparisons | % |

| Wound area/size reduction | 10 | 7.0 |

| Time to healing or rate of healing | 10 | 7.0 |

| Ulcer healing | 20 | 14.0 |

| Proportion of patients with healed wounds | 97 | 67.8 |

| No healing improvement | 5 | 3.5 |

| Length of hospitalization | 1 | 0.7 |

| Systematic reviews without a meta-analysis | n = 184 comparisons | % |

| Wound area/size reduction | 18 | 9.8 |

| Time to healing or rate of healing | 53 | 28.8 |

| Ulcer healing | 92 | 50.0 |

| Proportion of patients with healed wounds | 21 | 11.4 |

*Numbers do not add up to 99, as the systematic reviews contributed data to more than one category.

Study and patient characteristics

Thirty-four systematic reviews provided information about the patient population under study (Table 1; Additional file 3) and 21% included patients with diabetes. Six categories of complex wounds were examined: venous leg ulcers (31%), diabetic foot/leg ulcers (23%), pressure ulcers (17%), mixed arterial/venous leg wounds (14%), unspecified mixed complex wounds (9%), and infected surgical wounds (6%). The five most common interventions were adjuvant therapies (20%), dressings (16%), biologic agents (10%), other topical agents (9%), and other oral agents (7%). The five most common comparators were usual care (46%), dressings (25%), bandages (6%), support surfaces (5%), and other topical agents (4%). The duration of treatment ranged from 2 days to 160 months and the duration of follow-up ranged from 2 days to 195 months across the included studies in the systematic reviews.

A total of 327 treatment comparisons were included in the 99 systematic reviews. As such, only statistically significant results from systematic reviews with a meta-analysis are reported in our outcome results section below in the text. Specific results for all treatment comparisons can be found in Table 2. To facilitate the summary and comparison of a large number of reviews, we have presented the review results using positive, negative, or neutral conclusions (Tables 2,3,4,5,6,7); however, we have also included the statistical effect sizes from each of the included meta-analyses in Additional file 4.

Table 2.

Summary of evidence for venous ulcer management

| Outcome | Intervention | Systematic reviews with MA | Systematic reviews without MA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-quality* | Low/moderate quality | High-quality** | Low/moderate quality | ||

|

Wound size reduction

(MAs: 2; non-MAs: NA) [36,56] |

Cadexomer iodine (topical) | + | NA | NA | NA |

| Micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF) (oral) | NA | + | NA | NA | |

|

Time to healing or rate of healing

(MAs: 5 [34,39,44,45,56]; non-MAs: 1 [77]) |

Four-layer bandage | + | NA | NA | NA |

| MPFF (oral) | NA | + | NA | NA | |

| Stockings | NA | + | NA | +/− | |

| Silver-impregnated dressings | NA | – | NA | NA | |

| Applied freeze-dried keratinocyte lysate (topical) | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Collagenase (topical) | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Compression stockings | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Flavonoids + compression | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Intermittent pneumatic compression + compression | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Larval therapy | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Laser therapy | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Leg ulcer clinics, wound care program | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Multi-layer elastomeric high-compression | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Platelet-derived growth factor (oral) | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Rutosides (oral) | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Semi-occlusive dressings: foam, film, hyaluronic acid-derived dressings, collagen, cellulose, or alginate | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Stockings: multi-layer elastic system, multi-layer elastomeric (or non-elastomeric) high-compression regimens | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Sulodexide (oral) + compression | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Thromboxane α2 antagonists (oral) | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Topical negative pressure (vacuum-assisted closure) | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Ultrasound | NA | NA | NA | – | |

|

Ulcer healing

(MAs: 8 [29,30,39,51,62]; non-MAs: 5 [72,73,77,89,103,119]) |

Elastic high compression bandages | + | NA | NA | + |

| Cryopreserved allografts (Skin grafting) | NA | – | NA | +/− | |

| Cultured keratinocytes/epidermal grafts (Skin grafting) | NA | – | NA | +/− | |

| Fresh allografts (Skin grafting) | NA | – | NA | +/− | |

| Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (topical) | NA | + | NA | NA | |

| Pentoxifylline (oral) | + | NA | NA | NA | |

| Stockings | NA | + | NA | ||

| Tissue engineered skin | NA | + | NA | NA | |

| Electromagnetic therapy | NA | NA | + | NA | |

| Hydrocolloid (occlusive) dressings + compression | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Intermittent pneumatic compression (Flowtron, sequential gradient Jobst extremity pump) | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Maggot debridement therapy | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Mesoglycan (topical) | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Superficial venous surgery | NA | NA | + | NA | |

|

Proportion of patients with healed wounds

(MAs: 39 [21,23,25,30,31,36,40,45,46,48,52,53,55,58,62,64-67]; non-MAs: 2 [77,102]) |

Four-layer bandage | – | NA | ||

| Any laser (unspecified low level laser, ultraviolet therapy, non-coherent unpolarized red light) | NA | – | NA | NA | |

| Artificial skin graft and standard wound care | NA | – | NA | NA | |

| Autologous platelet-rich plasma (topical) | NA | – | NA | – | |

| Cadexomer iodine (topical) plus compression therapy | + | NA | NA | NA | |

| Systemic ciprofloxacin (oral) | NA | – | NA | NA | |

| Skin replacement therapy (Dermagraft) | NA | + | NA | + | |

| Elastic high compression bandages | + | NA | NA | NA | |

| Foam dressing | – | NA | NA | NA | |

| Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (perilesional injection) | NA | + | NA | + | |

| High frequency ultrasound | – | NA | NA | NA | |

| Honey (topical) | – | NA | NA | NA | |

| Hydrocolloid dressings | – | NA | NA | NA | |

| Hydrogel dressing | – | NA | NA | NA | |

| Intermittent pneumatic compression stockings | +/− | – | NA | NA | |

| Low frequency ultrasound | – | NA | NA | NA | |

| Multi-layer high compression bandages | +/− | NA | NA | + | |

| Pentoxifylline (oral) with and without compression | + | NA | NA | + | |

| Stockings | + | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Two-component (outer elastic) bandages | +/− | NA | NA | NA | |

| Ultrasound | NA | – | NA | NA | |

| Unna’s boot | NA | – | NA | NA | |

| Zinc (oral) | – | NA | NA | NA | |

| Antimicrobial (topical) | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Calcitonin gene-related peptide (topical) | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Prostaglandin EI (IV) | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Subfascial endoscopic perforator surgery | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Superficial vein surgery | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Systemic mesoglycan (IM, oral) + compression | NA | NA | NA | + | |

*At least one systematic review with meta-analysis and AMSTAR score ≥8.

**At least one systematic review without meta-analysis and AMSTAR score ≥8.

+ Effective (statistically significant difference between interventions and comparators); – No difference (no statistically significant difference between interventions and comparators); +/− Unknown (conflicting evidence between meta-analysis or indeterminate results); NA, No studies available; MA, Meta-analysis.

Table 3.

Summary of evidence for mixed arterial/venous ulcer management

| Outcome | Intervention | Systematic reviews with MA | Systematic reviews without MA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-quality* | Low/moderate quality | High-quality** | Low/moderate quality | ||

|

Wound area/size reduction

(MAs: 3) [34,65] |

Silver treatments (topical) and silver-impregnated dressings | NA | +/− | NA | NA |

| Ultrasound | NA | + | NA | NA | |

|

Ulcer healing

(MAs: NA; non-MAs: 6) [80,82-84,101,110] |

Antimicrobial (topical and oral) | NA | NA | NA | – |

| Electromagnetic therapy | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Honey (topical) | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Ketanserin ointment, 2% (topical) | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Standardized wound treatment protocol | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Silver releasing dressing | NA | NA | – | NA | |

|

Time to healing or rate of healing

(MAs: 5) [45,49,55,56] |

Topical negative pressure | NA | + | NA | NA |

| Four-layer bandage | + | NA | NA | NA | |

| Micronized purified flavonoid fraction (oral) | NA | + | NA | NA | |

| Micronized purified flavonoid fraction (oral) | NA | + | NA | NA | |

| Polyurethane (dressing) | – | NA | NA | NA | |

| Alginate (beads, paste + dressing, alginate dressing) | – | NA | NA | NA | |

|

Proportion of patients with healed wounds

(MAs: 3) [49,50] |

Silver dressings (topical or impregnated) | NA | – | NA | NA |

| Topical negative pressure | NA | + | NA | NA | |

*At least one systematic review with meta-analysis and AMSTAR score ≥8.

**At least one systematic review without meta-analysis and AMSTAR score ≥8.

+ Effective (statistically significant difference between interventions and comparators); – No difference (no statistically significant difference between interventions and comparators); +/− Unknown (conflicting evidence between meta-analysis or indeterminate results); NA, No studies available; MA, Meta-analysis.

Table 4.

Summary of evidence for diabetic ulcer management

| Outcome | Intervention | Systematic reviews with MA | Systematic reviews without MA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-quality* | Low/moderate quality | High-quality** | Low/moderate quality | ||

|

Wound area/size reduction

(MAs: NA; non-MAs: 2) [79,88] |

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (systemic + usual care) | NA | NA | NA | – |

| Stem cell therapy | NA | NA | NA | + | |

|

Time to healing or rate of healing

(MAs: NA; non-MAs: 3) |

Human skin equivalent | NA | NA | NA | + |

| Human cultured dermis | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Laser therapy and complex intervention | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| [79,88,95] | Platelet derived growth factors (topical) | NA | NA | NA | + |

| Pressure off-loading, felted foam | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Pressure off-loading, total contact or non-removable cast | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Stem cell therapy | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Skin grafts | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Topical negative pressure | NA | NA | – | NA | |

|

Ulcer healing

(MAs: 4 [24,35,57]; non-MAs: 10 [69,70,74,79,81,86,88,93,112,122]) |

Chinese herbal medicine + standard therapy | NA | + | NA | NA |

| Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (SC, IV) + antibiotics (oral, IV) | +/− | – | NA | +/− | |

| Alginate, foam, hydrogel, hydrocolloid dressings | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Alginate, hydrogel, hydrocellulose, semi-permeable membrane dressings | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid (oral), ofloxacin, imipenem/cilastatin, ampicillin/sulbactam (IV) | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Antibiotics, choice based on bone biopsy (IV, oral) | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Ayurvedic preparations (oral + topical) | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Clindamycin, fluoroquinolone, rifampicin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (oral, topical) +/− surgical intervention | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Compression | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Cultured human dermis | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Dressings + debridement (hydrogel) | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Early surgical intervention + antibiotics | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Electrical stimulation | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Endovascular or open bypass revascularization surgery of an ulcerated foot | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Foot care clinic interventions | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Growth factors (topical) | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Hydrogel, cadexomer iodine ointment, dressings, larval therapy, sugar (topical) systemic antibiotics | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Hyperbaric oxygen therapy | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (systemic + usual care) | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Imipenem/cilastatin, cefazolin, Ampicillin/sulbactam, Linezolid, Piperacillin/tazobactam. Amoxycillin + clavulanic acid, clindamycin hydrochloride (oral), pexiganan cream | NA | NA | – | NA | |

| Ketanserin (oral, topical) | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Larval therapy | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Lyophilized collagen, platelets and derived products (topical) | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Magnet and normothermic therapy | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Patient education | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Percutaneous flexor tenotomy | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Procaine + polyvinylpyrrolidone (IM) | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Resection of the complex wound | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Sharp debridement | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Skin grafts | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Stem cell therapy | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Superoxidized water and soap, povidone iodine (topical) | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Therapeutic footwear | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Thrombin-induced human platelet growth factor, recombinant platelet derived growth factor, recombinant basic fibroblast growth factor,arginine-glycine-aspartic acid peptide matrix (topical) | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Topical negative pressure | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Negative pressure therapy | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Total contact casting | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Ultrasound | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Zinc oxide tape | NA | NA | NA | + | |

|

No healing improvement/non-healed wounds

(MAs: 5) |

Chinese herbal medicine | NA | + | NA | NA |

| [22,33,35] | Hyaluronic acid-based scaffold and keratinocytes | – | NA | NA | NA |

| Hyaluronic acid-based derivative | + | NA | NA | NA | |

| Low frequency low intensity noncontact ultrasound | + | NA | NA | NA | |

|

Proportion of patients with healed wounds

(MAs: 18) [17-20,22,24,27,28,35,38,46,47,57-59] |

Alginate dressing | – | NA | NA | NA |

| Artificial skin graft and standard care | NA | + | NA | NA | |

| Chinese herbal medicine plus standard treatment | NA | + | NA | NA | |

| Skin graft (Dermagraft) | NA | – | NA | NA | |

| Fibrous-hydrocolloid (hydrofibre) dressing | – | NA | NA | NA | |

| Foam dressing | – | NA | NA | NA | |

| Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (SC, IV) + antibiotics (oral, IV) | + | + | NA | NA | |

| Hyaluronic acid-based scaffold and keratinocytes | – | NA | NA | NA | |

| Hydrogel dressing | + | + | NA | NA | |

| Hyperbaric oxygen therapy | – | NA | NA | ||

| Platelet-rich plasma | NA | + | NA | NA | |

| Skin replacement therapy (keratinocyte allograft, meshed skin autograft, split thickness autograft) | NA | + | NA | NA | |

*At least one systematic review with meta-analysis and AMSTAR score ≥8.

**At least one systematic review without meta-analysis and AMSTAR score ≥8.

+ Effective (statistically significant difference between interventions and comparators); – No difference (no statistically significant difference between interventions and comparators); +/− Unknown (conflicting evidence between meta-analysis or indeterminate results); NA, No studies available; MA, Meta-analysis.

Table 5.

Summary of evidence for pressure ulcer management

| Outcome | Intervention | Systematic reviews with MA | Systematic reviews without MA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-quality* | Low/moderate quality | High-quality** | Low/moderate quality | ||

|

Wound area/size reduction

(MAs: NA; non-MAs: 3) [78,87,94] |

Air-fluidized support | NA | NA | NA | + |

| Alternating pressure mattress, low-air-loss mattress, air-fluidized mattress | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Collagenase | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Collagenase, hydrogel dressings | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Electric current, electromagnetic therapy | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Foam, calcium alginate, radiant heat dressing, dextranomer powder dressings | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Hydrocolloid dressings | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Hydrocolloid, hydrogel wafer, hydrogel, occlusive polyurethane, transparent moisture-permeable dressings | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Hydrogel, cadexomer iodine, semelil gel, radiant heat, zinc salt spray, aluminum hydroxide, vitamin A ointment, streptokinase-streptodornase, dialysate, topical insulin, moist saline gauze and whirlpool, semelil dressings | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Low level laser therapy, laser and standard care | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Polarized light, monochromatic light and cadexomer iodine or hydrocolloid | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Ultrasound | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Vacuum therapy | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Vitamin C and ultrasound, consistent wound care and controlled nutritional support, vitamin C, zinc sulfate | NA | NA | NA | – | |

|

Time to healing or rate of healing

(MAs: NA; non-MAs: 3) [68,78,94] |

Ascorbic acid, high-protein diet, concentrated, fortified, collagen protein hydrolysate supplement, disease-specific nutrition treatment | NA | NA | NA | +/− |

| Amorphous hydrogel dressing derived from Aloe vera wound dressings | NA | NA | +/− | NA | |

| Electromagnetic therapy, low-intensity direct current, negative-polarity and positive-polarity electrotherapy, and alternating-polarity electrotherapy | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Hydrocolloid dressings | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Low air-loss beds | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Low level laser therapy | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Low-tech constant low-pressure supports | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Phenytoin ointment (topical) | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Seat cushions | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Topical negative pressure | NA | NA | NA | +/− | |

| Triple antibiotic ointment, active cream dressings | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Ultrasound | NA | NA | NA | – | |

|

Ulcer healing

(MAs: 8 [16,43,60,62,64]; non-MAs: 11 [75,76,78,85,90,92,94,97,99,104,106]) |

Air-fluidized bed/supports | + | + | +/− | NA |

| Air-fluidized beds, air suspension beds, foam replacement mattress | NA | NA | – | NA | |

| Alternating pressure surfaces | NA | NA | +/− | ||

| Alternating pressure surfaces (alternating pressure mattress + pressure relief cushion) | NA | NA | +/− | NA | |

| Ascorbic acid, zinc sulfate | NA | NA | +/− | NA | |

| Collagen protein, standard hospital diet and high protein, standard hospital diet and high protein and zinc and arginine and vitamin C | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Collagenase (topical) | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Fibroblast-derived dermal replacement | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Hydrocolloid, polyurethane, dextranomer, hydrogel, polyhydroxyethyl methacrylate, amino acid copolymer dressings | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Low air-loss mattress, alternating pressure mattress, air-fluidized mattress | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Phenytoin solution, antibiotics dressings | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Protease-modulating matrix, recombinant platelet-derived growth factor BB, nerve growth factor, transforming growth factor beta, granulocyte-macrophage/colony stimulating factor, basic fibroblast growth factor (topical) | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Saline spray containing Aloe vera, silver chloride and decyl glucoside, saline, whirlpool | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Topical negative pressure | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Topical negative pressure (vacuum assisted wound closure) | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Alternative foam mattress | + | NA | NA | NA | |

| Electrotherapy | + | NA | NA | NA | |

| High protein, oral nutritional support, enteral tube feeding | – | NA | NA | NA | |

| Hydrocolloid dressings | + | NA | NA | NA | |

| Polyurethane dressings | – | NA | NA | NA | |

|

Proportion of patients with healed wounds

(MAs: 25 [43,54,62]; non-MAs: 2 [78,94]) |

Collagenase debridement (topical) | NA | – | NA | NA |

| Dextranomer (beads + dry dressing) | NA | – | NA | NA | |

| Electrical stimulation | NA | – | NA | NA | |

| Electrotherapy | NA | – | NA | – | |

| Growth Factors (topical) | NA | – | NA | ||

| Hydrocolloid dressings | NA | +/− | NA | – | |

| Hydrogel (gel) | NA | + | NA | – | |

| Hydropolymer dressing | NA | – | NA | NA | |

| Low air-loss beds | – | – | NA | NA | |

| Low level laser therapy | NA | – | NA | NA | |

| Alternating pressure mattress | NA | +/− | NA | NA | |

| Non-contact normothermic dressing | NA | – | NA | NA | |

| Polyurethane dressings | NA | – | NA | – | |

| Ultrasound | – | – | NA | +/− | |

| Zinc supplement (oral) | NA | – | NA | ||

| Collagenase, dressings | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Laser therapy + moist saline gauze | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Monochromatic phototherapy, UV light | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Oxyquinoline, radiant heat, soft silicone, hydrogel or foam, active ointment with live yeast derivative, topical insulin (dressings) | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Resin salve absorbent dressings | NA | NA | NA | – | |

| Specialized foam mattress, alternating pressure mattress | NA | NA | NA | – | |

*At least one systematic review with meta-analysis and AMSTAR score ≥8.

**At least one systematic review without meta-analysis and AMSTAR score ≥8.

+ Effective (statistically significant difference between interventions and comparators); – No difference (no statistically significant difference between interventions and comparators); +/− Unknown (conflicting evidence between meta-analysis or indeterminate results); NA, No studies available; MA, Meta-analysis.

Table 6.

Summary of evidence for mixed complex wounds management

| Outcome | Intervention | Systematic reviews with MA | Systematic reviews without MA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-quality* | Low/moderate quality | High-quality** | Low/moderate quality | ||

| Wound area/size reduction (MAs:5) [21,32,41,42] | Autologous platelet-rich plasma/platelet-rich plasma (topical) | – | – | NA | NA |

| Silver releasing dressings | + | NA | NA | NA | |

| Topical negative pressure | NA | + | NA | NA | |

| Ulcer healing (MA: 1 [63]; non-MAs: 5 [91,100,105,107,111]) | Laser therapy | NA | – | NA | NA |

| Adhesive zinc oxide tape | NA | NA | + | NA | |

| Dextranomer polysaccharide beads or paste, cadexomer iodine polysaccharide beads or paste | NA | NA | _ | NA | |

| Enzymatic agents (topical) | NA | NA | – | NA | |

| Hydrogel dressings | NA | NA | – | NA | |

| Hyperbaric oxygen therapy | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| No-sting barrier film bandages | NA | NA | NA | + | |

| Silver releasing dressing, non-releasing silver-activated charcoal dressing, hydrocolloid silver Vaseline-impregnated dressing, silver coated dressing, hydrocolloid silver-releasing dressing, silver-releasing foam dressing | NA | NA | + | NA | |

| Topical negative pressure (open-cell foam dressing with continuous suction) | NA | NA | + | NA | |

| Proportion of patients with healed wounds (MAs: 10) [21,55,58,61,62,125] | Skin replacement (skin substitute) and standard care | NA | + | NA | NA |

| Skin replacement (dermal substitute) and standard care | NA | + | NA | NA | |

| Artificial skin grafts and standard care | NA | + | NA | NA | |

| Autologous platelet-rich plasma/platelet-rich plasma (topical) | NA | – | NA | NA | |

| Hydrocolloid dressings | – | + | NA | NA | |

| Laser therapy | – | NA | NA | NA | |

| Ultrasound | +/− | NA | NA | NA | |

*At least one systematic review with meta-analysis and AMSTAR score ≥8.

**At least one systematic review without meta-analysis and AMSTAR score ≥8.

+ Effective (statistically significant difference between interventions and comparators); – No difference (no statistically significant difference between interventions and comparators); +/− Unknown (conflicting evidence between meta-analysis or indeterminate results); NA, No studies available); MA, Meta-analysis.

Table 7.

Summary of evidence for infected surgical wounds management

| Outcome | Intervention | Systematic reviews with MA | Systematic reviews without MA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-quality* | Low/moderate quality | High-quality** | Low/moderate quality | ||

| Proportion of patients with healed wounds (MAs: 1) [37] | Topical negative pressure/vacuum-assisted closure | NA | + | NA | NA |

| Vacuum-assisted closure | NA | + | NA | NA | |

| Wound area/size reduction (MAs: NA; non-MAs: 2) [71,108] | Alginate dressings | NA | NA | – | NA |

| Foam dressings | NA | NA | – | NA | |

| Time to healing or rate of healing (MAs: NA; non-MAs: 5) [68,71,96,108,109] | Alginate dressings | NA | NA | +/− | NA |

| Aloe vera dermal gel (topical) | NA | NA | +/− | NA | |

| Dextranomer polysaccharide bead dressings | NA | NA | +/− | NA | |

| Foam dressings | NA | NA | – | NA | |

| Gauze + Aloe vera dressings | NA | NA | +/− | NA | |

| Honey (topical) | NA | NA | + | ||

| Hydrocolloid dressings | NA | NA | – | NA | |

| Plaster casting | NA | NA | + | NA | |

| Polyurethane foam and sheets dressings | NA | NA | +/− | NA | |

| Silicone elastomer foam dressings and polyurethane foam dressings | NA | NA | – | NA | |

| Topical negative pressure | NA | NA | – | NA | |

| Ulcer healing (MAs: NA; non-MAs: 2) [71,108] | Dextranomer polysaccharide bead dressings | NA | NA | +/− | NA |

| Polyurethane foam dressings | NA | NA | +/− | NA | |

*At least one systematic review with meta-analysis and AMSTAR score ≥8.

**At least one systematic review without meta-analysis and AMSTAR score ≥8.

+ Effective (statistically significant difference between interventions and comparators); – No difference (no statistically significant difference between interventions and comparators); +/− Unknown (conflicting evidence between meta-analysis or indeterminate results); NA, No studies available; MA, Meta-analysis.

Methodological quality appraisal

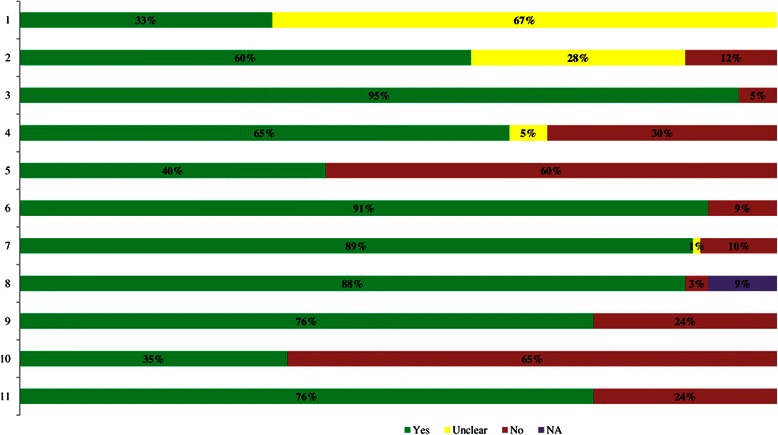

Almost half (45%) of the systematic reviews were deemed high quality with an AMSTAR score ≥8 out of a possible 11 (Figure 2; Additional file 5). Many systematic reviews did not provide a list of excluded studies from screening potentially relevant full-text articles (60%) or address publication bias (65%). Conversely, 95% searched at least two electronic databases, 91% provided the characteristics of included studies, and 89% adequately used the quality appraisal results in formulating conclusions. Half of the systematic reviews including a meta-analysis had an AMSTAR score ≥8, and 40% of the systematic reviews without a meta-analysis had an AMSTAR score ≥8.

Figure 2.

AMSTAR methodological quality results. NA, Not applicable. 1. A priori design. 2. Duplicate selection/DA. 3. Literature search. 4. Publication status. 5. List of studies. 6. Study characteristics. 7. Quality assessed. 8. Quality used. 9. Methods appropriate. 10. Publication bias assessed. 11. Conflicts stated.

Outcome results for venous leg ulcers

Wound area/size reduction

Two systematic reviews including two meta-analyses examined venous leg ulcer area/size reduction [56] (Table 2; Additional file 4), one of which had an AMSTAR score ≥8 [36]. Topical cadexomer iodine [36] and oral micronized purified flavonoid fraction [56] were more effective than placebo in each meta-analysis comparing these interventions.

Time to healing or rate of healing

Five systematic reviews including six meta-analyses [34,39,44,45,56] and one systematic review without a meta-analysis [77] (Table 2; Additional files 4 and 6) examined the time to healing for venous leg ulcers. Two of these had an AMSTAR score ≥8 [44,45].

Two systematic reviews (AMSTAR score ≥8) including two meta-analyses found that four-layer bandages were more effective than short stretch bandages [44] and compression systems [45]. One systematic review including two meta-analyses found conflicting results for bandages versus stockings [39]. Oral micronized purified flavonoid fraction was more effective than placebo in one meta-analysis [56].

Ulcer healing

Five systematic reviews including eight meta-analyses [29,30,39,51,62] and five systematic reviews without a meta-analysis [72,73,77,89,103] (Table 2; Additional files 4 and 6) examined venous leg ulcer healing. Four of these had an AMSTAR score ≥8 [30,62,73,89].

Elastic high compression was more effective than multi-layer inelastic compression in a systematic review (AMSTAR score ≥8) with a meta-analysis [62] and stockings were more effective than bandages in another meta-analysis [39]. Tissue engineered skin was more effective than dressings in one meta-analysis [51], topical granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor was more effective than placebo in another meta-analysis [29], and oral pentoxifylline was more effective with (or without) compression than placebo in another meta-analysis (AMSTAR score ≥8) [30].

Proportion of patients with healed wounds

Nineteen systematic reviews with 39 meta-analyses [21,23,25,30,31,36,40,45,46,48,52,53,55,58,62,64-67] and two systematic reviews without a meta-analysis [77,102] (Table 2; Additional files 4 and 6) examined the proportion of patients with healed venous leg ulcers. Twelve of these had an AMSTAR score ≥8 [23,25,30,31,36,40,45,52,55,62,64,67].

Multi-layered, high compression bandages reduced ulcers compared with single layer bandages in two meta-analyses [62,67]. Elastic high compression was more effective than inelastic bandages [45] and versus inelastic compression bandages (AMSTAR score ≥8) [67] in two meta-analyses. Intermittent pneumatic compression was more effective than compression stockings or Unna’s boot in one meta-analysis (AMSTAR score ≥8) [67] and high compression stockings were more effective than compression bandages in another meta-analysis (AMSTAR score ≥8) [62]. Two-layer stockings were more effective than short-stretch bandages in another meta-analysis [44]. Ultrasound was more effective than no ultrasound in one meta-analysis [65] and cleaning wounds with cadexomer iodine plus compression therapy was more effective than standard care in another meta-analysis (AMSTAR score ≥8) [36]. Skin replacement therapy was more effective than standard compression therapy in one meta-analysis [46] and oral pentoxifylline with (or without) compression was more effective than placebo in two meta-analyses (AMSTAR score ≥8) [30]. Periulcer injection with granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor was more effective than control in another meta-analysis [53].

Outcome results for mixed arterial/venous leg ulcers

Wound area/size reduction

Two systematic reviews including three meta-analyses examined wound area/size reduction for mixed arterial/venous leg ulcers [34,65] (Table 3; Additional file 4). None had an AMSTAR score ≥8. One meta-analysis found topical silver and silver dressings more effective than placebo or conservative wound care or non-silver therapies [34] and another that ultrasound was more effective than standard treatment or placebo [65].

Time to healing or rate of healing

Four systematic reviews including five meta-analyses examined the time to healing for mixed arterial/venous leg ulcers [45,49,55,56] (Table 3; Additional file 4). Two had an AMSTAR score ≥8 [45,55]. One meta-analysis found topical negative pressure more effective than conventional therapy [49], a second found oral micronized purified flavonoid more effective than placebo or standard compression [56], and a third found that four-layer bandage was more effective than compression systems [45].

Ulcer healing

Six systematic reviews without a meta-analysis examined ulcer healing for mixed arterial/venous leg ulcers [80,82-84,101,110] (Table 3; Additional file 6). Two had an AMSTAR score ≥8 [80,84]. Details of these study results can be found in Additional file 6.

Proportion of patients with healed wounds

Two systematic reviews including three meta-analyses examined the proportion of patients with healed mixed arterial/venous wounds [49,50] (Table 3; Additional file 4). None had an AMSTAR score ≥8. Topical negative pressure was more effective than conventional therapy in one meta-analysis [49].

Outcome results for diabetic foot/leg ulcers

The following outcome results were only reported in systematic reviews without meta-analysis: wound area/size reduction (n = 2) [79,88] and time to healing or rate of healing (n = 3) [79,88,95]. Details of these study results can be found in Additional file 6.

Ulcer healing

Three systematic reviews including four meta-analyses [24,35,57] and 10 systematic reviews without a meta-analysis [69,70,74,79,81,86,88,93,98,112] (Table 4; Additional files 4 and 6) examined healing improvements of diabetic foot/leg ulcers. Three had an AMSTAR score ≥8 [24,74,98].

One meta-analysis found that subcutaneous or intravenous granulocyte colony-stimulating factor plus oral or intravenous antibiotics was more effective than control (high quality) [24]. Another meta-analysis found that Chinese herbal medicine (see Table 4 and Additional file 4 for the exact preparation) plus unspecified standard therapy was more effective than standard therapy alone [35].

No healing improvement or non-healed wounds

Three systematic reviews including five meta-analyses [22,33,35] examined no healing improvement for diabetic wounds (Table 4; Additional file 4). Two of these had an AMSTAR score ≥8 [22,33].

Hyaluronic acid derivative was more effective than standard care in one meta-analysis (AMSTAR score ≥8) [22]. Low frequency low intensity noncontact ultrasound was more effective than sharps debridement in two meta-analyses (AMSTAR score ≥8) [33] and Chinese herbal medicine (see Additional file 4 for the exact preparation) plus unspecified standard therapy was more effective than standard therapy alone in another meta-analysis [35].

Proportion of patients with healed wounds

Fifteen systematic reviews including 18 meta-analyses [17-20,22,24,27,28,35,38,46,47,57-59] (Table 4; Additional file 4) examined the proportion of patients with healed diabetic foot and leg ulcers. Eight of these had an AMSTAR score ≥8 [17,18,20,22,24,27,28,59].

Hydrogel dressings were more effective than basic wound dressings, basic contact dressings, and gauze in three meta-analyses (two with an AMSTAR score ≥8) [17,19,28]. Artificial skin grafts were more effective than usual care in one meta-analysis [58] and skin replacement therapy was more effective than usual care in another [47]. Chinese herbal medicine (see Additional file 4 for the exact preparation) plus unspecified standard therapy was more effective than standard therapy alone in a meta-analysis [35] and subcutaneous or intravenous granulocyte colony-stimulating factor was more effective than usual care in another (AMSTAR score ≥8) [24]. Finally, a meta-analysis found platelet-rich plasma more effective than control [38].

Outcome results for pressure ulcers

The following outcome results were only reported in systematic reviews without meta-analysis: wound area/size reduction (n = 3) [78,87,94] and time to healing or rate of healing (n = 3) [68,78,94]. Details of these study results can be found in Additional file 6.

Ulcer healing

Five systematic reviews reporting on eight meta-analyses [16,43,60,64,62] and 11 systematic reviews without a meta-analysis [75,76,78,85,90,92,94,97,99,104,106] (Table 5; Additional files 4 and 6) focused on pressure ulcer healing. Of these, eight had an AMSTAR score ≥8 [16,60,62,64,75,76,90,106].

Hydrocolloid dressings were more effective than usual care in a meta-analysis (AMSTAR score ≥8) [64], electrotherapy was more effective than sham therapy in another meta-analysis (AMSTAR score ≥8) [62], and air-fluidized beds were more effective than standard care or conventional mattresses in three meta-analyses [43,60,125]. In addition, alternate foam mattresses were more effective than standard foam mattresses in a meta-analysis (AMSTAR score ≥8) [60].

Proportion of patients with healed wounds

Three systematic reviews including 25 meta-analyses [43,54,62] and two systematic reviews without a meta-analysis [78,94] (Table 5; Additional files 4 and 6) examined the proportion of patients with healed pressure ulcers. Only one had an AMSTAR score ≥8 [62].

One meta-analysis found that hydrocolloid dressings were more effective than traditional dressings and another that hydrogel dressings were more effective than hydrocolloid dressings [43]. Different brands of alternating pressure mattresses were more effective than others in a meta-analysis [43].

Outcome results for mixed complex wounds (unspecified)

Wound area/size reduction

Four systematic reviews including five meta-analyses examined the area/size reduction of mixed complex wounds (unspecified) [21,32,41,42] (Table 6; Additional file 4). Two had an AMSTAR score ≥8 [41,42]. Silver-impregnated dressings were more effective than dressings not containing silver in a meta-analysis (AMSTAR score ≥8) [41]. Topical negative pressure was more effective than standard wound care in another meta-analysis [32].

Ulcer healing

One systematic review including a meta-analysis [63] and five systematic reviews without a meta-analysis [91,100,105,107,111] (Table 6; Additional files 4 and 6) examined ulcer healing for mixed complex wounds. Three had an AMSTAR score ≥8 [91,107,111].

Proportion of patients with healed wounds

Five systematic reviews including 10 meta-analyses [21,55,58,61,62] (Table 6; Additional file 4) examined the proportion of patients with healed complex wounds. Two had an AMSTAR score ≥8 [55,62]. Hydrocolloid dressings were more effective than conventional dressings in a meta-analysis [61] and ultrasound was more effective than no ultrasound in another (AMSTAR score ≥8) [62]. In addition, artificial skin grafts were more effective than standard care in three meta-analyses [58].

Outcome results for surgical wound infections

The following outcome results were only reported in systematic reviews without meta-analysis: wound area/size reduction (n = 2) [71,108], time to healing or rate of healing (n = 5) [68,71,96,108,109], and ulcer healing (n = 2) [71,108]. Details of these study results can be found in Additional file 6.

Proportion of patients with healed wounds

One systematic review including a meta-analysis (AMSTAR <8) found that topical negative pressure was more effective than standard treatment [37] (Table 7; Additional file 4).

Length of hospital stay

One systematic review and meta-analysis (AMSTAR <8) found that vacuum-assisted closure was more effective than conventional therapy for decreasing the length of hospital stay associated with surgical wound infections [26] (Table 7; Additional file 4).

Discussion

We conducted a comprehensive overview of systematic reviews to identify optimal interventions for complex wounds. Data from 99 systematic reviews were scrutinized and interventions that are likely optimal were identified. These reviews examined numerous treatments and comparators and used different outcomes to assess effectiveness. Frequently, treatments considered as the intervention in one review were administered to the control in another. This renders the interpretation of our findings difficult.

We found that some interventions are likely to be effective based on data from systematic reviews including a meta-analysis with an AMSTAR score ≥8. For venous leg ulcers, four-layer bandages [44,45], elastic high compression [62], oral pentoxifylline with (or without) compression [30], compression bandages (multi-layer, elastic) [62,67], high compression [62] or multi-layer stockings [45], and wound cleansing with cadexomer iodine plus compression therapy [36] were effective compared with usual care. Only four-layer bandages [45] were effective in healing mixed arterial/venous leg ulcers versus compression systems. For diabetic foot/leg ulcers, subcutaneous or intravenous granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [24], hyaluronic acid derivative [22], low frequency, low intensity noncontact ultrasound [33], and hydrogel dressings [17,28] were effective interventions compared with usual care. For pressure ulcers, hydrocolloid dressings [64], electrotherapy [62], air-fluidized beds [60], and alternate foam mattresses [60] were effective compared with usual care. For mixed complex wounds, silver dressings [41] and ultrasound [62] were found to be more effective than no treatment. Finally, effective treatments were not identified for surgical wound infections amongst those with an AMSTAR score ≥8 including a meta-analysis. It is important to note that many of these interventions had conflicting results versus other comparators or were based on meta-analyses including few studies with a small number of patients. As such, these results should be interpreted with caution.

There are some limitations to our overview of systematic reviews. An inherent drawback of including systematic reviews is that the studies included in each of the reviews will have been published well before the search date. The inclusion of close to 100 systematic reviews, however, provides a breadth of information that is unlikely to significantly change with the inclusion of recently published studies. Although we appraised the methodological quality of the included reviews, we did not assess the risk of bias in the included studies in the systematic reviews. This is because a risk of bias tool for systematic reviews currently does not exist, but we are aware of one being developed by the Cochrane Collaboration [126]. Furthermore, we only included systematic reviews that were disseminated in English due to resource constraints. However, we attempted contacting authors to receive English translations. In addition, although we included five unpublished systematic reviews, we attempted to obtain unpublished data from a further 10 systematic reviews that were available as conference abstracts, yet we didn’t receive a response from the review authors. As such, our findings are likely representative of published literature written in English. Since we did not conduct a meta-analysis, we were unable to formally test for publication bias.

Our results suggest the need for a network meta-analysis [127], given the numerous interventions and comparators available and examined across the literature. Policy-makers focus their decisions at the systems level so require information on all treatment comparisons available. Patients and their healthcare providers need to know if the treatment they are prescribed or recommending is the most effective and safest compared with all others available. Conducting a high-quality, comprehensive systematic review and network meta-analysis is the only feasible tool available to examine multiple treatment comparisons. As the healthcare system shifts towards more complex problems and a resource-scarce environment, systematic reviews and meta-analysis of only one treatment comparison become obsolete. This is indeed the case for complex wound care interventions; despite the availability of almost 100 systematic reviews, optimal management is still unclear. Network meta-analysis also allows the ranking of all treatments for each effectiveness and safety outcome examined, making it a particularly attractive tool for decision-makers.

Almost half of the included systematic reviews were rated as being of high methodological quality according to the AMSTAR tool [13]. Consistent methodological shortcomings include not using a protocol to guide their conduct, not including a list of excluded studies at the full-text level of screening, and not addressing or referring to publication bias. Results reported in systematic reviews with higher scores on the AMSTAR tool are likely the most reliable. Furthermore, some studies only gave wound care patients two days of treatment or followed patients for two days. The utility of these short studies is questionable and studies of longer duration are recommended.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results confirm that there are numerous interventions that can be utilized for patients with complex wounds. However, few treatments were consistently effective throughout the literature. Clinicians and patients can use our results as a guide towards tailoring effective treatment according to type of wound. Planned future analysis of this data through network meta-analysis will further assist decision-makers as it will permit multiple treatment comparisons as well as the ranking of the effectiveness of all available wound care interventions.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the Toronto Central Local Health Integrated Network. ACT is funded by a Canadian Institutes for Health Research/Drug Safety and Effectiveness Network (CIHR/DSEN) New Investigator Award on Knowledge Synthesis Methodology. SES is funded by a CIHR tier 1 Research Chair in Knowledge Translation.

We thank Dr. James Mahoney and Chris Shumway from the Toronto Central Local Health Integrated Network who provided invaluable feedback on our original report. As well, we thank Geetha Sanmugalingham for screening some citations and full-text articles, John Ivory for screening some citations, Judy Tran for obtaining the potentially relevant full-text articles, and Wasifa Zarin and Inthuja Selvaratnam for helping to format the paper.

Abbreviation

- AMSTAR

Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews

Additional files

Classification of wound care interventions and comparators. Lists the interventions and the corresponding comparators for each wound care treatment/comparator identified in our review.

MEDLINE search strategy. Lists MEDLINE search terms.

Systematic review characteristics. Lists the characteristics of studies included in the overview of reviews.

Meta-analysis results. Provides relevant findings from the included reviews with a meta-analysis.

AMSTAR results for each systematic review. Results of the AMSTAR quality assessment for included reviews.

Non-meta-analysis results. Provides relevant findings from the included reviews without a meta-analysis.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ACT conceived the study, helped obtain funding for the study, screened citations, abstracted data, appraised quality, analyzed the data, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. JA coordinated the study, screened citations and full-text articles, abstracted data, appraised quality, cleaned the data, generated tables and figures, and helped write the manuscript. AH, AV, PAK, CW screened citations and full-text articles, abstracted data, appraised quality and edited the manuscript. AH also located full-texts of conference abstracts, and scanned reference lists. EC screened citations and full-text articles, peer-reviewed the literature search, and edited the manuscript. LP screened citations and full-text articles, abstracted data, appraised quality and conducted the literature search. WH abstracted data, created data tables, formatted the paper, and edited the manuscript. SES conceived the study, designed the study, obtained the funding, interpreted the results, and edited the manuscript. All authors interpreted the results, read, edited, and approved the final paper. SES accepts full responsibility for the finished article, had access to all of the data, and controlled the decision to publish. SES affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned and registered have been explained.

Contributor Information

Andrea C Tricco, Email: triccoa@smh.ca.

Jesmin Antony, Email: antonyj@smh.ca.

Afshin Vafaei, Email: vafaeia@smh.ca.

Paul A Khan, Email: khanp@smh.ca.

Alana Harrington, Email: harringtona@smh.ca.

Elise Cogo, Email: cogoe@smh.ca.

Charlotte Wilson, Email: charlotte.wilson@rogers.com.

Laure Perrier, Email: l.perrier@utoronto.ca.

Wing Hui, Email: wing.hui@mail.utoronto.ca.

Sharon E Straus, Email: sharon.straus@utoronto.ca.

References

- 1.Akagi I, Furukawa K, Miyashita M, Kiyama T, Matsuda A, Nomura T, et al. Surgical wound management made easier and more cost-effective. Oncol Lett. 2012;4:97–100. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferreira MC, Tuma P, Jr, Carvalho VF, Kamamoto F. Complex wounds. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2006;61:571–578. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322006000600014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stansby G, Avital L, Jones K, Marsden G, Guideline Development Group Prevention and management of pressure ulcers in primary and secondary care: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2014;348:g2592. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adderley U, Smith R. Topical agents and dressings for fungating wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003948.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abidia A, Laden G, Kuhan G, Johnson BF, Wilkinson AR, Renwick PM, et al. The role of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in ischaemic diabetic lower extremity ulcers: a double-blind randomised-controlled trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003;25:513–518. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apelqvist J, Ragnarson TG. Cavity foot ulcers in diabetic patients: a comparative study of cadexomer iodine ointment and standard treatment. An economic analysis alongside a clinical trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 1996;76:231–235. doi: 10.2340/0001555576231235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harding KG, Morris HL, Patel GK. Science, medicine and the future: healing chronic wounds. BMJ. 2002;324:160–163. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7330.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brolmann FE, Ubbink DT, Nelson EA, Munte K, van der Horst CM, Vermeulen H. Evidence-based decisions for local and systemic wound care. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1172–1183. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ubbink DT, Santema TB, Stoekenbroek RM. Systemic wound care: a meta-review of cochrane systematic reviews. Surg Technol Int. 2014;24:99–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. www.cochrane-handbook.org.

- 11.National Institute for Health Research (NIH). PROSPERO database http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/Prospero/.

- 12.Sampson M, McGowan J, Cogo E, Grimshaw J, Moher D, Lefebvre C. An evidence-based practice guideline for the peer review of electronic search strategies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:944–952. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shea BJ, Hamel C, Wells GA, Bouter LM, Kristjansson E, Grimshaw J, et al. AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1013–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shea BJ, Bouter LM, Peterson J, Boers M, Andersson N, Ortiz Z, et al. External validation of a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews (AMSTAR) PLoS One. 2007;2:e1350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tricco AC, Tetzlaff J, Pham B, Brehaut J, Moher D. Non-Cochrane vs. Cochrane reviews were twice as likely to have positive conclusion statements: cross-sectional study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stratton RJ, Ek AC, Engfer M, Moore Z, Rigby P, Wolfe R, et al. Enteral nutritional support in prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2005;4:422–450. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dumville JC, Deshpande S, O’Meara S, Speak K. Hydrocolloid dressings for healing diabetic foot ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009099.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dumville JC, O’Meara S, Deshpande S, Speak K. Alginate dressings for healing diabetic foot ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009110.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edwards J, Stapley S. Debridement of diabetic foot ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003556.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kranke P, Bennett MH, Martyn-St James M, Schnabel A, Debus SE. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for chronic wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004123.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinez-Zapata MJ, Marti-Carvajal AJ, Sola I, Exposito JA, Bolibar I, Rodriguez L, et al. Autologous platelet-rich plasma for treating chronic wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006899.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voigt J, Driver VR. Hyaluronic acid derivatives and their healing effect on burns, epithelial surgical wounds, and chronic wounds: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Wound Repair Regen. 2012;20:317–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2012.00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkinson EA. Oral zinc for arterial and venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001273.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cruciani M, Lipsky BA, Mengoli C, de Lalla F. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factors as adjunctive therapy for diabetic foot infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;5 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cullum N, Al-Kurdi D, Bell-Syer SEM. Therapeutic ultrasound for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001180.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Damiani G, Pinnarelli L, Sommella L, Tocco MP, Marvulli M, Magrini P, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure therapy for patients with infected sternal wounds: a meta-analysis of current evidence. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:1119–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dumville JC, Deshpande S, O’Meara S, Speak K. Foam dressings for healing diabetic foot ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009111.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dumville JC, O’Meara S, Deshpande S, Speak K. Hydrogel dressings for healing diabetic foot ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009101.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu X, Sun H, Han C, Wang X, Yu W. Topically applied rhGM-CSF for the wound healing: a systematic review. Burns. 2011;37:729–741. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jull AB, Arroll B, Parag V, Waters J. Pentoxifylline for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001733.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson EA, Mani R, Thomas K, Vowden K. Intermittent pneumatic compression for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001899.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suissa D, Danino A, Nikolis A. Negative-pressure therapy versus standard wound care: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:498e–503e. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Voigt J, Wendelken M, Driver V, Alvarez OM. Low-frequency ultrasound (20–40 kHz) as an adjunctive therapy for chronic wound healing: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis of eight randomized controlled trials. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2011;10:190–199. doi: 10.1177/1534734611424648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carter MJ, Tingley-Kelley K, Warriner RA., 3rd Silver treatments and silver-impregnated dressings for the healing of leg wounds and ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:668–679. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen M, Zheng H, Yin LP, Xie CG. Is oral administration of Chinese herbal medicine effective and safe as an adjunctive therapy for managing diabetic foot ulcers? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:889–898. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Meara S, Al-Kurdi D, Ologun Y, Ovington LG. Antibiotics and antiseptics for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003557.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan A, Cauda R, Concia E, Esposito S, Sganga G, Stefani S, et al. Consensus document on controversial issues in the treatment of complicated skin and skin-structure infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:S39–S53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Villela DL, Santos VL. Evidence on the use of platelet-rich plasma for diabetic ulcer: a systematic review. Growth Factors. 2010;28:111–116. doi: 10.3109/08977190903468185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amsler F, Willenberg T, Blattler W. In search of optimal compression therapy for venous leg ulcers: a meta-analysis of studies comparing diverse [corrected] bandages with specifically designed stockings. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:668–674. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jull AB, Rodgers A, Walker N. Honey as a topical treatment for wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005083.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lo SF, Chang CJ, Hu WY, Hayter M, Chang YT. The effectiveness of silver-releasing dressings in the management of non-healing chronic wounds: a meta-analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:716–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martinez-Zapata MJ, Marti-Carvajal A, Sola I, Bolibar I, Angel Exposito J, Rodriguez L, et al. Efficacy and safety of the use of autologous plasma rich in platelets for tissue regeneration: a systematic review. Transfusion (Paris). 2009;49:44–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Health Quality Ontario. Management of chronic pressure ulcers: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2009;9(3):1–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.O’Meara S, Tierney J, Cullum N, Bland JM, Franks PJ, Mole T, et al. Four layer bandage compared with short stretch bandage for venous leg ulcers: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials with data from individual patients. BMJ. 2009;338:b1344. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Meara S, Cullum NA, Nelson EA. Compression for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000265.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barber C, Watt A, Pham C, Humphreys K, Penington A, Mutimer K, et al. Influence of bioengineered skin substitutes on diabetic foot ulcer and venous leg ulcer outcomes. J Wound Care. 2008;17:517–527. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2008.17.12.31766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blozik E, Scherer M. Skin replacement therapies for diabetic foot ulcers: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:693–694. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flemming K, Cullum NA. Laser therapy for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sadat U, Chang G, Noorani A, Walsh SR, Hayes PD, Varty K. Efficacy of TNP on lower limb wounds: a meta-analysis. J Wound Care. 2008;17:45–48. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2008.17.1.28371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chambers H, Dumville JC, Cullum N. Silver treatments for leg ulcers: a systematic review. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15:165–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jones JE, Nelson EA. Skin grafting for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001737.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palfreyman S, Nelson EA, Michaels JA. Dressings for venous leg ulcers: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;335:244. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39248.634977.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O’Donnell TF, Jr, Lau J. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of wound dressings for chronic venous ulcer. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:1118–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sari BA, Flemming K, Cullum NA, Wollina U. Therapeutic ultrasound for pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001275.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bouza C, Munoz A, Amate JM. Efficacy of modern dressings in the treatment of leg ulcers: a systematic review. Wound Repair Regen. 2005;13:218–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2005.130302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coleridge-Smith P, Lok C, Ramelet AA. Venous leg ulcer: a meta-analysis of adjunctive therapy with micronized purified flavonoid fraction. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;30:198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cruciani M, Lipsky BA, Mengoli C, de Lalla F. Are granulocyte colony-stimulating factors beneficial in treating diabetic foot infections? A meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:454–460. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.2.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ho C, Tran K, Hux M, Sibbald G, Campbell K. Artificial skin grafts in chronic wound care: a meta-analysis of clinical efficacy and a review of cost-effectiveness. In: Technology Report no 52. Ottawa: Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment; 2005.

- 59.Roeckl-Wiedmann I, Bennett M, Kranke P. Systematic review of hyperbaric oxygen in the management of chronic wounds. Br J Surg. 2005;92:24–32. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cullum N, Deeks J, Sheldon TA, Song F, Fletcher AW. Beds, mattresses and cushions for pressure sore prevention and treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Singh A, Halder S, Menon GR, Chumber S, Misra MC, Sharma LK, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on hydrocolloid occlusive dressing versus conventional gauze dressing in the healing of chronic wounds. Asian J Surg. 2004;27:326–332. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]