Abstract

Fungal plant pathogens are persistent and global food security threats. To invade their hosts they often form highly specialized infection structures, known as appressoria. The cAMP/ PKA- and MAP kinase-signaling cascades have been functionally delineated as positive-acting pathways required for appressorium development. Negative-acting regulatory pathways that block appressorial development are not known. Here, we present the first detailed evidence that the conserved Target of Rapamycin (TOR) signaling pathway is a powerful inhibitor of appressorium formation by the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. We determined TOR signaling was activated in an M. oryzae mutant strain lacking a functional copy of the GATA transcription factor-encoding gene ASD4. Δasd4 mutant strains could not form appressoria and expressed GLN1, a glutamine synthetase-encoding orthologue silenced in wild type. Inappropriate expression of GLN1 increased the intracellular steady-state levels of glutamine in Δasd4 mutant strains during axenic growth when compared to wild type. Deleting GLN1 lowered glutamine levels and promoted appressorium formation by Δasd4 strains. Furthermore, glutamine is an agonist of TOR. Treating Δasd4 mutant strains with the specific TOR kinase inhibitor rapamycin restored appressorium development. Rapamycin was also shown to induce appressorium formation by wild type and Δcpka mutant strains on non-inductive hydrophilic surfaces but had no effect on the MAP kinase mutant Δpmk1. When taken together, we implicate Asd4 in regulating intracellular glutamine levels in order to modulate TOR inhibition of appressorium formation downstream of cPKA. This study thus provides novel insight into the metabolic mechanisms that underpin the highly regulated process of appressorium development.

Author Summary

Many fungal pathogens destroy important crops by first gaining entrance to the host using specialized appressorial cells. Understanding the molecular mechanisms that control appressorium formation could provide new routes for managing severe plant diseases. Here, we describe a previously unknown regulatory pathway that suppresses appressorium formation by the rice pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae. We provide evidence that a mutant M. oryzae strain, unable to form appressoria, accumulates intracellular glutamine that, in turn, inappropriately activates a conserved signaling pathway called TOR. Reducing intracellular glutamine levels, or inactivating TOR, restored appressorium formation to the mutant strain. TOR activation is thus a powerful inhibitor of appressorium formation and could be leveraged to develop sustainable mitigation practices against recalcitrant fungal pathogens.

Introduction

Fungal pathogens cause some of the most devastating crop diseases and constitute globe-wide challenges to socioeconomic growth and food security. To facilitate entry into their hosts, many filamentous pathogens form highly specialized infection structures, known as appressoria, on the leaf surface [1 – 3]. Appressoria breach the host cuticle and allow access to the underlying epidermal cells. Appressoria have varying morphologies that range from undifferentiated germ tube swellings to discrete dome-shaped cells separated from the germ tube tip by septa [1, 4, 5]. In addition to facilitating plant invasion, appressoria can act as sites of effector delivery and thus mediate the molecular host-pathogen interaction [6, 7]. Despite their widespread occurrence and long-acknowledged importance to plant health, detailed mechanistic descriptions of the regulatory pathways necessary for appressorium formation are limited to two molecular pathways, the cAMP/ PKA- and MAP kinase—signaling cascades [2, 5, 8 – 10].

One filamentous pathogen that has been widely studied as a model to understand the molecular biology of appressorium development is the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae [5, 10]. This pathogen is notable for the serious threat it poses to rice production worldwide, destroying 10–30% of the global rice harvest each year. Infection begins when a three-celled spore of M. oryzae adheres to the surface of a rice leaf and germinates. At 4 hours post inoculation (hpi), the germ tube hooks and begins to swell. By 8 hpi the swelling has developed into a dome-shaped appressorium that becomes melanized, pressurized, and infection competent by 16–24 hpi [3, 5, 11]. The tightly regulated morphological transitions that occur during appressorium development are dependent on a range of external cues, including surface hardness and hydrophobicity [12, 13], that act to trigger internal regulatory processes such as adenylate cyclase activation and cAMP production [5, 8, 9]. cAMP acts by binding the regulatory subunit of protein kinase A (PKA) to release the protein kinase A catalytic subunit (cPKA). Genetic lesions in the cAMP/ PKA signaling pathway significantly reduce appressorium formation and those that do form are small and non-functional [5, 14, 15]. Appressorium formation can be remediated by the addition of cAMP when pathway mutations occur upstream of PKA. Moreover, activating cPKA by exogenous cAMP can induce appressorium formation in wild type strains (WT) on non-inductive hydrophilic surfaces [14]. Another internal regulatory process that has been well documented to control appressorium morphogenesis is the Pmk1 MAP kinase signaling cascade. The MAP kinase orthologue of Fus3/Kss1, Pmk1, is essential for appressorial formation and works in a MAP kinase cascade instigated by hydrophobicity and cutin monomer sensing [9, 10, 16]. Disruptions to MAP kinase signaling abolish the initiation of appressorium formation, and the germ tubes of Δpmk1 mutants remain undifferentiated [17]. Thus, the positive-acting cAMP/ PKA and MAP kinase morphogenetic regulatory cascades are integral to appressorium initiation and development.

Here, we present genetic and biochemical evidence for a previously unknown, negative-acting regulator that inhibits appressorium formation downstream of cPKA. In a previous study [18], we showed that the GATA family [19] transcription factor Asd4 was essential for sporulation, optimal growth on undefined complete media (CM) and appressorium formation [18]. Spores of Δasd4 mutant strains lacking a functional ASD4 allele due to homologous gene replacement produced germ tubes that could not elaborate appressoria at the apical tips. However the mechanisms involved, and any relationship of the GATA factor Asd4 to cAMP/ PKA and MAP kinase signaling, were unknown [18]. Here, we show that Asd4 regulates the expression of genes involved in nitrogen assimilation and glutaminolysis in order to modulate intracellular glutamine pools. Elevated intracellular pools of glutamine in Δasd4 mutant strains activated the target of rapamycin (TOR) nutrient-sufficiency signaling pathway [20] and prevented appressorium formation. Remediating glutamine levels in Δasd4 mutant strains by genetic manipulation, or bypassing the elevated glutamine signal using the specific TOR inhibitor rapamycin, promoted appressorium formation by Δasd4 mutant strains. Rapamycin treatment also induced appressorium formation in ΔcpkA mutant strains. However, cAMP treatment did not restore appressorium formation to Δasd4 mutant strains, and rapamycin treatment did not stimulate appressorium formation in Δpmk1 mutant strains. When considered together, the results presented here implicate Asd4, glutamine metabolism and TOR as fundamental but previously unknown regulators of plant disease that act on the cAMP/ cPKA signaling pathway to control appressorium formation.

Results

Asd4 is involved in nitrogen metabolism

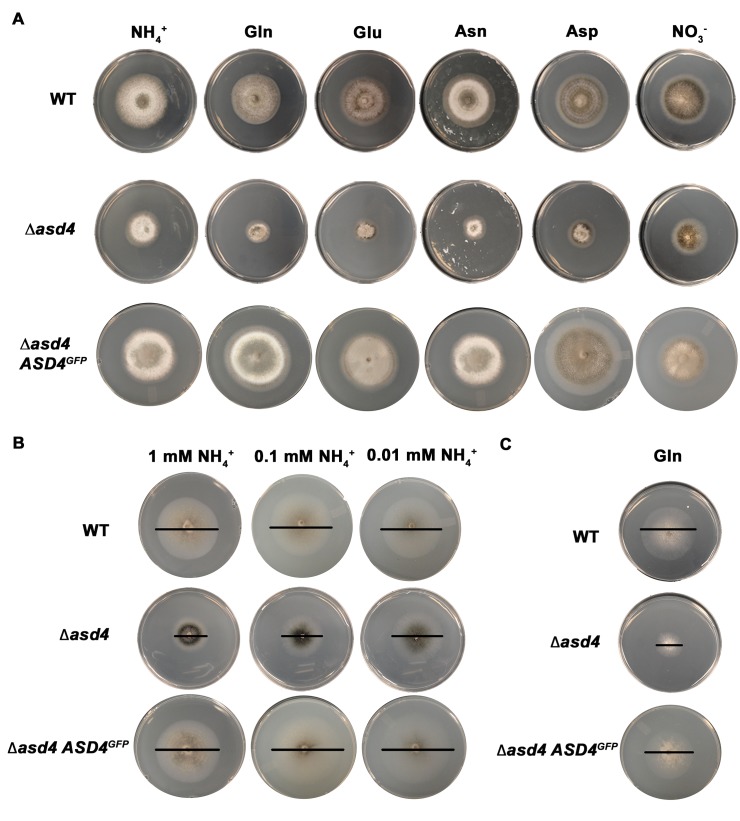

To investigate the role of Asd4 in appressorium formation, we first turned our attention to the connection between Asd4 function and optimal axenic growth on plate media. In common with other fungi, M. oryzae preferentially utilizes glucose and ammonium (NH4 +) over other carbon and nitrogen sources [21, 22]. When grown on defined minimal media containing 1% (w/v) glucose (GMM) and 10 mM NH4 + as the sole carbon and nitrogen source, respectively, Δasd4 mutant strains, compared to the Guy11 wild type (WT) isolate used in our studies, were reduced for growth (Fig 1A and S1 Table). Reduced growth on GMM with 10 mM NH4 + was similarly observed for Δasd4 mutant strains generated from the M. oryzae reference isolate 70–15 (S1A Fig) and, consistent with previous observations, loss of ASD4 function in 70–15 also abolished appressorium formation (S1B Fig). Reduced growth on NH4 +- media was not observed, however, for a Δasd4 ASD4 GFP complementation strain expressing Asd4 fused to GFP from its native promoter in the Guy11-derived Δasd4 mutant background (Fig 1A). The Δasd4 Asd4 GFP complementation strain was also restored for appressoria formation on hydrophobic surfaces (S1C Fig) and Asd4GFP localized, as expected for a transcription factor, to the appressorial nucleus (S1D Fig). Thus, the role of Asd4 in growth and appressorium formation is not idiosyncratic to the Guy11 isolate (nor does the Δasd4 phenotype result from off-target gene deletion effects) but is rather a fundamental function of this GATA factor in M. oryzae.

Fig 1. ASD4 is involved in nitrogen assimilation.

(A) Δasd4 mutant strains were grown for 10 days on minimal media (MM) containing 1% (w/v) glucose (GMM) and 10 mM of the indicated sole nitrogen sources. L-isomers were used throughout this study. (B) After 10 days, Δasd4 growth was not further attenuated on GMM containing low concentrations of ammonium as the sole nitrogen. (C) Strains were grown for 10 days on MM containing 10 mM L-glutamine as the sole carbon and nitrogen source. WT = wild type Guy11 isolate, Δasd4 ASD4GFP = Δasd4 complementation strain expressing Asd4 fused to GFP. Bars are added as a visual aid to the plate images in (B) and (C) to demarcate colony size.

Additional plate testing revealed that Δasd4 mutant strains (but not WT or Δasd4 ASD4 GFP complementation strains) were also defective for growth on glucose MM (GMM) regardless of the nitrogen source, including compounds less preferred than NH4 + such as amino acids and nitrate (NO3 -) (Fig 1A and S1 Table). Δasd4 radial growth was not further restricted by low (< 10 mM) concentrations of NH4 +, amino acids or GABA as sole nitrogen sources (Fig 1B and S1 Table), suggesting Asd4 is not involved in nitrogen uptake. Asd4 is also not involved in sugar utilization because we observed poor growth of Δasd4 mutant strains on MM with L-glutamine as a sole carbon and nitrogen source (Fig 1C); on MM lacking glucose but containing the less preferred, derepressing sugar xylose with L-glutamine or L-glutamate as a nitrogen source (S2 Table); and on MM with L-glutamine or L-GABA as sole carbon sources and with NH4 + as a nitrogen source (S2 Table). Taken together, these observations indicate Asd4 is not required for nitrogen uptake (Fig 1B) or sugar metabolism (S2 Table), but is required for nitrogen metabolism (Fig 1A) including glutaminolysis (Fig 1C).

Asd4 regulates the expression of genes involved in nitrogen assimilation and glutaminolysis

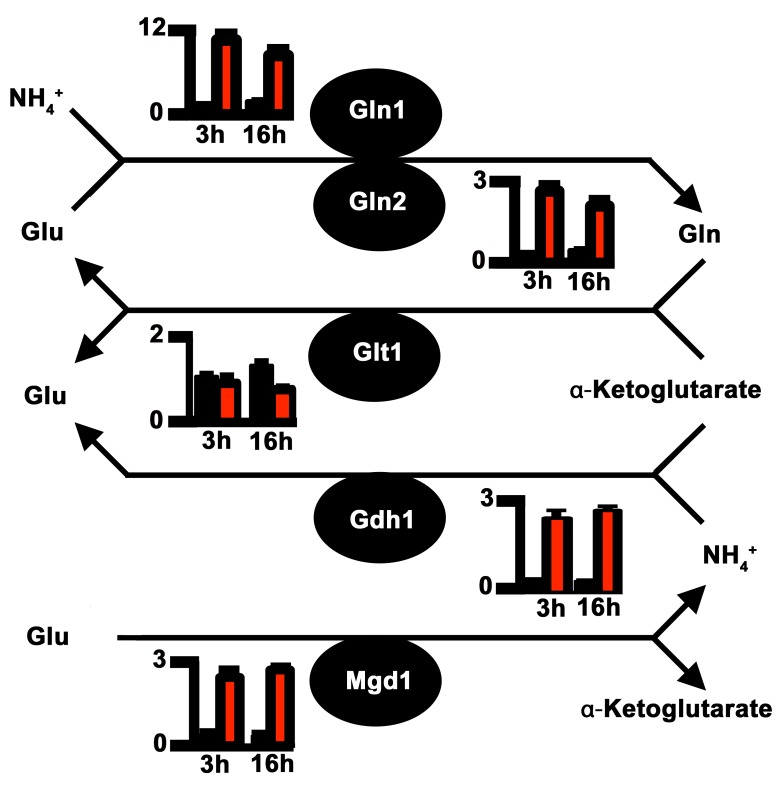

Impaired nitrogen assimilation in Δasd4 mutant strains could account for its poor growth on all the nitrogen sources tested regardless of the carbon source (Fig 1A and 1C). Based on sequence homology, we identified genes in the M. oryzae genome [23] encoding likely components of the nitrogen assimilatory and glutaminolytic pathways [24 – 26], including two glutamine synthetase-encoding orthologues, GLN1 and GLN2 (Fig 2 and S3 Table). To determine the expression profiles of these genes we used quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) to analyze RNA extracted from WT and Δasd4 mutant strains grown in liquid shake GMM with 10 mM NH4 + for 3 and 16 h [21]. Loss of Asd4 function induced the expression of GLN1 and up-regulated the expression of GLN2, GDH1 and MGD1 compared to WT (Figs 2 and S2). Thus, genes for assimilating and metabolizing nitrogen are misregulated in Δasd4 mutant strains when compared to WT.

Fig 2. Proposed pathway of nitrogen assimilation and glutaminolysis in M. oryzae based on sequence homology.

Nitrogen is assimilated and distributed via glutamine synthetase (Gln1 and Gln2) and glutamate synthase (Glt1) or anabolic NADP-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase (Gdh1) and Gln1-2 [24, 25]. Glutaminolysis [26] involves NAD-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase (Mgd1). Enzymes are depicted as solid circles with the adjacent bar graphs showing the relative expression levels of the encoding genes in WT (black bar) and Δasd4 mutant strains (red bar) following 3 h and 16 h growth in GMM with 10 mM NH4 + as the sole nitrogen source. Results were normalized against the expression of the β-tubulin gene TUB2. Values are the average of three results from at least two independent biological replicates. Error bars are standard deviation.

To understand how the gene expression perturbations in Fig 2might affect nitrogen metabolism, we measured the steady-state concentrations of amino acids in WT and Δasd4 mycelia following growth in GMM with 10 mM NH4 + for 16 h using LC-MS/MS (Table 1). Steady-state intracellular pools of glutamine were significantly (Student’s t-test p ≤ 0.05) increased in Δasd4 mycelial extracts compared to WT (Table 1). This suggests that defects in glutaminolysis (Fig 1C) and/ or the misregulation of nitrogen assimilation genes (Fig 2) significantly affected glutamine biosynthesis and turnover in Δasd4 mutant strains. The concentrations of other intracellular amino acids pools were also altered in Δasd4 mutant strains under these growth conditions. For instance, Table 1shows that steady-state intracellular pools of aspartate, alanine and arginine were reduced, while asparagine and valine levels were increased, in Δasd4 mycelia compared to WT. Collectively, these results demonstrate that glutamine turnover and the distribution of assimilated nitrogen into other nitrogenous compounds is perturbed in Δasd4 mutant strains compared to WT. These observations are consistent with our plate tests (Fig 1A, 1B and 1C) showing Δasd4 strains were impaired in nitrogen source utilization and glutaminolysis.

Table 1. aTRAQ values for mycelial amino acid concentrations following growth on minimal media with 1% (w/v) glucose and 10 mM NH4 +.

| Strains | WT | Δasd4 | Δasd4 Δgln1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acids | p-value | LSD a | Mean (μmole/g) b | SD c | Mean (μmole/g) b | SD c | Mean (μmole/g) b | SD c |

| Alanine | 0.001 | 12.455 | 75.53 | 10.11 | 47.89 | 2.86 | 41.69 | 2.48 |

| Arginine | 0.003 | 7.113 | 24.44 | 5.59 | 12.31 | 2.29 | 7.95 | 1.22 |

| Asparagine | 0.009 | 1.897 | 5.15 | 0.94 | 8.67 | 0.95 | 6.00 | 0.97 |

| Aspartate | 0.031 | 0.577 | 1.23 | 0.38 | 0.47 | 0.17 | 0.53 | 0.28 |

| Glutamate | 0.404 | - | 6.04 | 2.70 | 8.98 | 0.62 | 6.13 | 1.58 |

| Glutamine | 0.002 | 19.398 | 40.41 | 10.00 | 91.6 | 6.00 | 56.95 | 7.72 |

| Glycine | 0.030 | 0.438 | 2.25 | 0.24 | 1.88 | 0.18 | 1.60 | 0.23 |

| Histidine | 0.001 | 0.425 | 2.51 | 0.28 | 1.71 | 0.19 | 1.26 | 0.14 |

| Isoleucine | 0.009 | 0.628 | 1.52 | 0.18 | 2.67 | 0.17 | 2.48 | 0.48 |

| Leucine | 0.549 | - | 1.47 | 0.17 | 1.63 | 0.29 | 1.74 | 0.35 |

| Lysine | 0.018 | 0.643 | 2.40 | 0.37 | 2.46 | 0.08 | 1.49 | 0.40 |

| Methionine | 0.710 | - | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| Phenylalanine | 0.574 | - | 0.50 | 0.07 | 0.52 | 0.04 | 0.56 | 0.09 |

| Proline | 0.149 | - | 2.76 | 0.47 | 3.93 | 0.46 | 4.07 | 1.14 |

| Serine | 0.114 | 1.988 | 4.78 | 0.54 | 4.12 | 0.42 | 3.81 | 0.44 |

| Threonine | 0.0002 | 0.587 | 3.37 | 0.50 | 5.65 | 0.03 | 4.09 | 0.06 |

| Tryptophan | 0.234 | - | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.04 |

| Tyrosine | 0.848 | - | 3.98 | 0.60 | 4.71 | 1.11 | 5.09 | 3.91 |

| Valine | 0.004 | 0.854 | 3.89 | 0.43 | 5.89 | 0.48 | 4.63 | 0.37 |

aLSD = Fisher's Least Significant Difference.

bValues correspond to the average of three independent repetitions.

cStandard deviation.

Asd4-dependent silencing of the glutamine synthetase—Encoding gene GLN1 is essential for appressorium formation

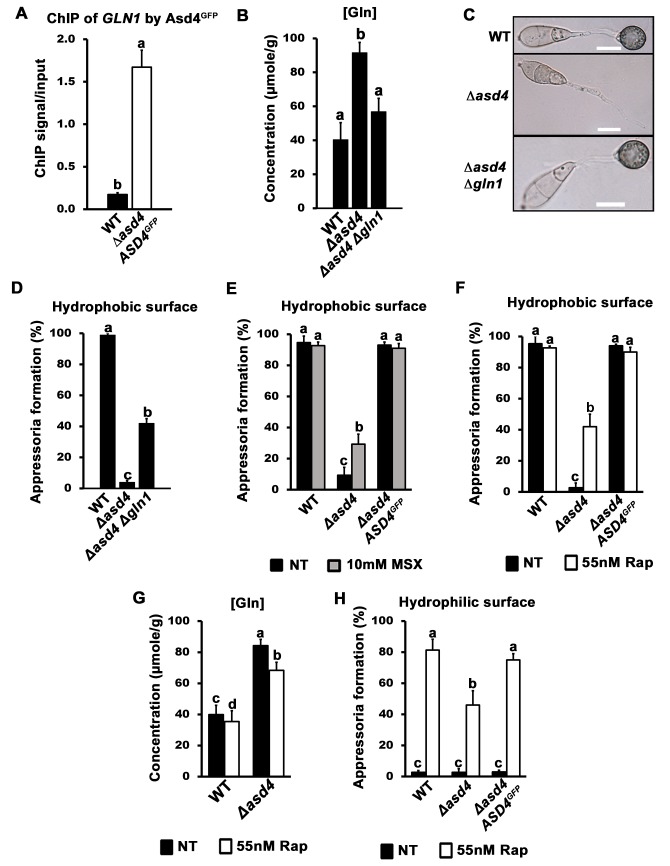

We hypothesized that the misregulation of GLN1/2, MGD1 and GDH1 gene expression might account for the accumulation of glutamine in Δasd4 mutant strains compared to WT. Of particular note, GLN1 expression was detected in Δasd4 mutant strains on NH4 + media but not in WT (Figs 2 and S2). To determine how GLN1 expression might contribute to the observed Δasd4 phenotypes, we first characterized how GLN1 was expressed under different developmental and growth conditions. We found that, in contrast to GLN2, GLN1 gene expression was not detected in WT during appressoria development [27] (S3A Fig). Furthermore, our qPCR transcript analysis showed that, unlike GLN2, GLN1 was not expressed during early in planta colonization by WT (S3B Fig), or during the growth of WT on a range of nitrogen sources in addition to NH4 + (S3C Fig). However, GLN1 was highly expressed in Δasd4 mutant strains compared to WT on all the nitrogen sources tested (S3C Fig). These expression data prompted us to perform chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) in order to determine whether Asd4 interacted with GLN1 DNA in vivo. Using Anti-GFP, we immunoprecipitated chromatin samples from Δasd4 ASD4 GFP strains, and from the WT lacking the ASD4 GFP allele, following growth on 1% GMM with 10 mM NH4 + as the sole nitrogen source. ChIP-qPCR detected a significant enrichment (Student’s t-test p ≤ 0.05) of GLN1 DNA in ChIP samples from strains expressing Asd4GFP compared to WT (Fig 3A). The GLN1 signal/ input ratio for Asd4GFP ChIP was 9.6-fold higher than for WT ChIP (ie. the background), thus demonstrating a physical interaction between Asd4GFP and GLN1 DNA that is consistent with the transcriptional data (Figs 2, S2 and S3). Also, the positioning of the ChIP-qPCR primers used to detect GLN1 suggests Asd4 binding occurs in the 5 ‘ region of the gene, which might be consistent with the presence of predicted GATA-binding sequences in the promoter region of GLN1 [23]. Taken together, we conclude that GLN1 is a cryptic glutamine synthetase-encoding gene normally silenced in WT by Asd4.

Fig 3. A real or perceived reduction in intracellular glutamine levels restores appressorium formation to Δasd4 mutant strains.

(A) Asd4 physically interacts with the GLN1 promoter in vivo following growth on GMM with 10 mM NH4 + as the sole nitrogen source. ChIP was performed using Anti-GFP. The eluted GLN1 DNA signal, normalized against the input control, was significantly (Student’s t-test p ≤ 0.05) enriched in Δasd4 ASD4GFP ChIP samples compared to WT controls lacking Asd4GFP. (B) Steady-state intracellular concentrations of glutamine were quantified using LC-MS/MS analysis of amino acid extracts from dried fungal mycelia of the indicated strains following growth on GMM + 10 mM NH4 + media. Values are the average of three independent biological replicates. (C) Appressorial development of WT, Δasd4 and Δasd4 Δgln1 strains on artificial hydrophobic surfaces (coverslips) at 24 hpi. Scale bar is 10 μm. (D) Appressorial formation rates of WT, Δasd4 and Δasd4 Δgln1 mutant strains on artificial hydrophobic surfaces (coverslips). (E) Treatment of Δasd4 spores with the glutamine synthetase inhibitor 10 mM L-methionine sulphoximine (MSX) partially remediated appressorium formation. (F) Δasd4 mutant strains formed appressoria at 24 hpi on artificial hydrophobic surfaces following treatment with 55 nM rapamycin (Rap). (G) Steady-state intracellular concentrations of glutamine were quantified following growth of the indicated strains on GMM + 10 mM NH4 + media with and without 55 nM rapamycin. Values are the average of three independent biological replicates. (H) Treating spore suspensions with 55 nM rapamycin induced appressorium formation by WT and Δasd4 mutant strains on non-inductive hydrophilic surfaces. NT is untreated. (A-B, D-H) Error bars are standard deviation. Bars with different letters are significantly different (Student’s t-test p ≤ 0.05). (D-F, H) Values are the average of the number of appressoria formed at 24 hpi from 50 spores per coverslip, repeated in triplicate.

To determine if GLN1 expression in Δasd4 mutant strains affected appressorium development, we deleted GLN1 from the WT and Δasd4 genomes using targeted homologous gene replacement. As expected for a gene that is not normally expressed (S3 Fig), loss of GLN1 in WT did not affect colony morphology, sporulation, appressorium formation or pathogenicity (S4A–S4D Fig). However, in the Δasd4 Δgln1 double mutant strain, steady-state intracellular glutamine pools were restored to WT levels when grown on NH4 +-media (Fig 3B and Table 1), indicating that inappropriate GLN1 expression in Δasd4 mutant strains affects nitrogen assimilation and/ or distribution into amino acids. Furthermore, Δasd4 Δgln1 germ tubes were found to develop melanized appressorium on artificial hydrophobic surfaces (Fig 3C) at a significantly higher rate (Student’s t-test p ≤ 0.05) than Δasd4 mutant strains (Fig 3D). Thus, Asd4-dependent silencing of GLN1 might be required for maintaining intracellular glutamine pools at levels optimal for promoting appressorium formation in WT.

GLN2 expression is also upregulated in Δasd4 mutant strains compared to WT (although not to the same extend as GLN1; S2 Fig) and deleting GLN2 in Δasd4 mutant strains might also affect glutamine levels and appressorium formation. However, despite numerous attempts, we were unable to generate Δasd4 Δgln2 double mutant strains in this study, perhaps indicating that whereas GLN2 functions without GLN1 under a range of developmental conditions (S3 Fig), GLN1 cannot substitute for GLN2 in Δasd4 mutant strains. The relationship between GLN2 and ASD4 requires more articulation but does not affect our central conclusion that altering intracellular glutamine levels in Δasd4 mutant strains due to GLN1 expression affects appressorium formation.

Appressorium formation requires a glutamine-dependent signal

In addition to restoring glutamine levels, deleting GLN1 in the Δasd4 background also restored intracellular pool levels of asparagine and valine (Table 1). However, three lines of evidence suggested that the reduction in intracellular glutamine levels (rather than global changes in nitrogen assimilation and distribution) was linked to appressorium formation in the Δasd4 Δgln1 double mutant compared to the Δasd4 parental strain. Firstly, Δasd4 Δgln1 strains continued to grow poorly on NH4 +- media (S4E Fig), and aspartate, alanine and arginine levels were not remediated in the Δasd4 Δgln1 double mutant strain (Table 1). This indicates that nitrogen assimilation and/ or distribution remained defective in Δasd4 Δgln1 strains but did not prevent appressorium formation. Secondly, treating Δasd4 spores with the glutamine synthetase inhibitor L-methionine sulphoximine (MSX), shown in yeast to reduce intracellular glutamine levels [28], significantly improved (Student’s t-test p ≤ 0.05) Δasd4 appressorium formation rates on artificial surfaces (Fig 3E). Thirdly, in yeast [20, 28, 29] and mammals [30], glutamine (amongst other metabolites) acts as a signal to activate the conserved target of rapamycin (TOR) pathway and facilitate growth under nutrient-sufficient conditions. The specific TOR kinase inhibitor rapamycin inactivates TOR and induces starvation-like responses in yeast and mammals [20, 31, 32]. Fig 3F shows that treatment of Δasd4 spores with rapamycin significantly (Student’s t-test p ≤ 0.05) induced appressorium formation on inductive, artificial hydrophobic surfaces compared to untreated controls (Fig 3F). Rapamycin treatment also induced appressorium formation in Δasd4 mutant strains derived from 70–15 (S5 Fig). Intracellular glutamine levels were not affected by treatment with rapamycin and remained elevated in Δasd4 mutant strains compared to the Guy11 WT (Fig 3G), suggesting rapamycin bypasses the elevated glutamine signal in Δasd4 mutant strains to promote appressoria formation. Moreover, whereas WT appressorium formation rates were not affected by rapamycin treatment on inductive hydrophobic surfaces (Fig 3F), rapamycin treatment significantly (Student’s t-test p ≤ 0.05) enhanced the rate of appressorial formation for WT and Δasd4 mutant strains on non-inductive hydrophilic surfaces (glass coverslips) (Fig 3H). Taken together, these results suggest that (i) Asd4-dependent glutamine metabolism and the resulting glutamine pool sizes are important determinants of appressorium formation, and (ii) glutamine signaling might regulate appressorium formation via the TOR signaling pathway.

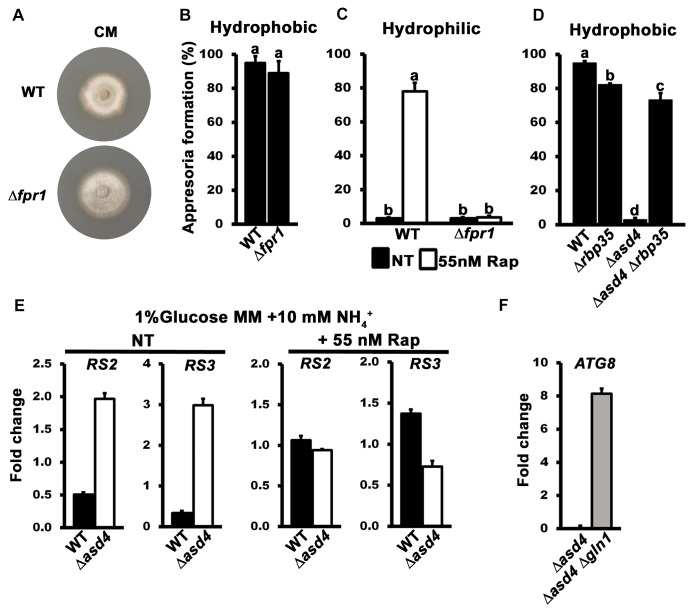

Evidence for a functional connection between Asd4 and TOR signaling

The previous section suggested that Asd4 might modulate intracellular glutamine levels to control appressorium formation via TOR. We next sought more evidence for a functional connection between Asd4 and TOR signaling. Firstly, we intended to confirm that rapamycin could affect appressorium formation by acting directly on TOR, as opposed to having off-target effects on unrelated processes. To achieve this goal, we identified MoFRP1, the M. oryzae homologue of the yeast FRP1 gene encoding the FK506/rapamycin-binding protein FKBP12. The FKBP-rapamycin complex physically interacts with TOR to inhibit its activity, and TOR is the conserved target of FKBP-rapamycin [20]. However, FKBP12 does not interact with TOR in the absence of rapamycin and consequently in yeast, FRP1 deletion strains are viable but are not responsive to rapamycin [33]. We generated Δfpr1 mutant strains that were indistinguishable from WT on plates (Fig 4A) and formed appressoria on hydrophobic surfaces (Fig 4B). These results are consistent with previous studies that showed how the Botrytis cinerea FKBP12 ortholog is not required for plant pathogenicity [34]. However, rapamycin failed to induce appressorium formation by Δfpr1 mutant strains on hydrophilic surfaces (Fig 4C). These results demonstrate that rapamycin treatment requires FKBP12 to affect appressorium formation and thus, a priori, FKBP-rapamycin must be acting on its conserved target TOR.

Fig 4. The TOR signaling pathway is misregulated in Δasd4 mutant strains.

(A) The colony morphology of Δfpr1 mutant strains on complete media was not altered compared to WT. Strains were grown for 10 days. (B) Appressorial formation rates of Δfpr1 mutant strains were not significantly different (Student’s t-test p > 0.5) from WT on hydrophobic artificial surfaces. (C) Treating spore suspensions with 55 nM rapamycin (Rap) did not induce appressorium formation in Δfpr1 mutant strains on non-inductive hydrophilic surfaces compared to WT. (D) Appressorial formation rates on artificial hydrophobic surfaces were significantly elevated in an Δasd4 Δrbp35 double mutant compared to the Δasd4 single mutant. (E) The expression of the M. oryzae ribosomal protein genes RS2 and RS3 was increased in Δasd4 mutant strains compared to WT after growth in 1% GMM with 10 mM NH4 + for 16h. Treatment with 55 nM Rap restored the expression of RS2 and RS3 in Δasd4 mutant strains to WT levels. Expression levels were normalized against TUB2 gene expression and are given as relative fold changes. (F) ATG8 gene expression is upregulated in Δasd4 Δgln1 mutant strains compared to the Δasd4 mutant when normalized against TUB2 gene expression. (B-D) Error bars are standard deviation. Bars with different letters are significantly different (Student’s t-test p ≤ 0.05). Values are the average of the number of appressoria formed at 24 hpi from 50 spores per coverslip, repeated in triplicate. NT = no treatment. (E-F) Values are the mean of three independent replicates. Error bars are SD.

Secondly, we sought genetic evidence that TOR inactivation restored appressoria formation in Δasd4 mutant strains in order to corroborate our pharmacological data. We hypothesized that disrupting the sole copy of the TOR-encoding geneTOR1 in Δasd4 mutant strains would restore appressorium formation. However, we were unable to generate Δtor1 mutant deletion strains in Guy11 or Δasd4 strains, likely due to an essential role for the TOR protein in cell viability. This is consistent with studies in Fusarium graminearum that were also unable to yield targeted deletions of the single FgTOR gene [35]. Future work might involve gene silencing of TOR1 rather than deletion, but we did not attempt that here, in part because gene silencing in M. oryzae has not been developed to the stage where targeted genes can be switched off at specific stages of development, and in part because we had an alternative strategy involving the Δrbp35 mutant strain. RBP35 encodes an M. oryzae RNA-binding protein involved in processing RNA transcripts essential for rice root colonization [36]. Loss of RBP35 leads to downregulation of the TOR signaling pathway [36, 37]. We hypothesized that deleting ASD4 in the Δrbp35 mutant strain would permit appressorium formation because the downregulation of TOR signaling resulting from the Δrbp35 allele would counteract the upregulation of the TOR signaling pathway resulting from intracellular glutamine accumulation in the Δasd4 mutant strain. Fig 4D shows that, as predicted, the Δasd4 Δrbp35 double mutant produced significantly more appressoria on inductive, hydrophobic surfaces than the Δasd4 single mutant strain. This provides genetic evidence that TOR signaling lies downstream of Asd4 and is activated in the Δasd4 mutant strains to prevent appressorium formation.

Finally, we sought to demonstrate that TOR signaling was perturbed in Δasd4 strains by analyzing the expression of TOR readout genes in WT and Δasd4 mutant strains. RS2 and RS3 encode ribosomal proteins that have been shown previously to be elevated in expression when TOR is active but reduced in expression when TOR is inactivated following rapamycin treatment [38]. Fig 4E shows that the RS2 and RS3 genes were elevated in expression in Δasd4 mutant strains following axenic growth compared to WT, and this expression pattern was reversed when rapamycin was added to the growth media. Furthermore, ATG8 is an autophagy gene whose expression is repressed by active TOR. Autophagy is required for appressorium maturation in M. oryzae [39], and is a processes inhibited by active TOR in yeast and mammals [40]. Fig 4F shows that ATG8 expression was repressed in Δasd4 mutant strains following axenic growth compared to the Δasd4 Δgln1 double mutant.

When considered together, these results indicate that Asd4 acts upstream of TOR (via glutamine) in order to regulate appressoria formation. Consequently, TOR signaling is perturbed in Δasd4 mutant strains.

TOR activation inhibits appressorium formation downstream of cAMP/ PKA signaling

A previously unknown outcome of this work is the discovery that rapamycin treatment can generate appressoria on non-inductive hydrophilic surfaces (Fig 3H). cAMP treatment, or mutations that constitutively activate cAMP/ PKA signaling, also enable appressoria to form on non-inductive hydrophilic surfaces [8]. We next asked if a relationship existed between TOR and the cAMP/ PKA- and MAP kinase-signaling pathways by first treating Δasd4 spores with cAMP. cAMP treatment did not restore appressorium formation to Δasd4 mutant strains on either inductive hydrophobic (Fig 5A) or, in contrast to WT, on non-inductive hydrophilic surfaces (Fig 5B). This indicates that activated TOR in Δasd4 mutant strains blocks appressorium formation downstream of cPKA. However, although downstream of cAMP/ PKA signaling, Asd4 is not under direct cPKA control because if so, cPKA would be required for Asd4 function and Δcpka strains would be expected to phenocopy Δasd4 strains. However, S6A Fig shows that Δcpka mutant strains grew better than Δasd4 strains on NH4 + media. Thus, CPKA is not likely epistatic to ASD4.

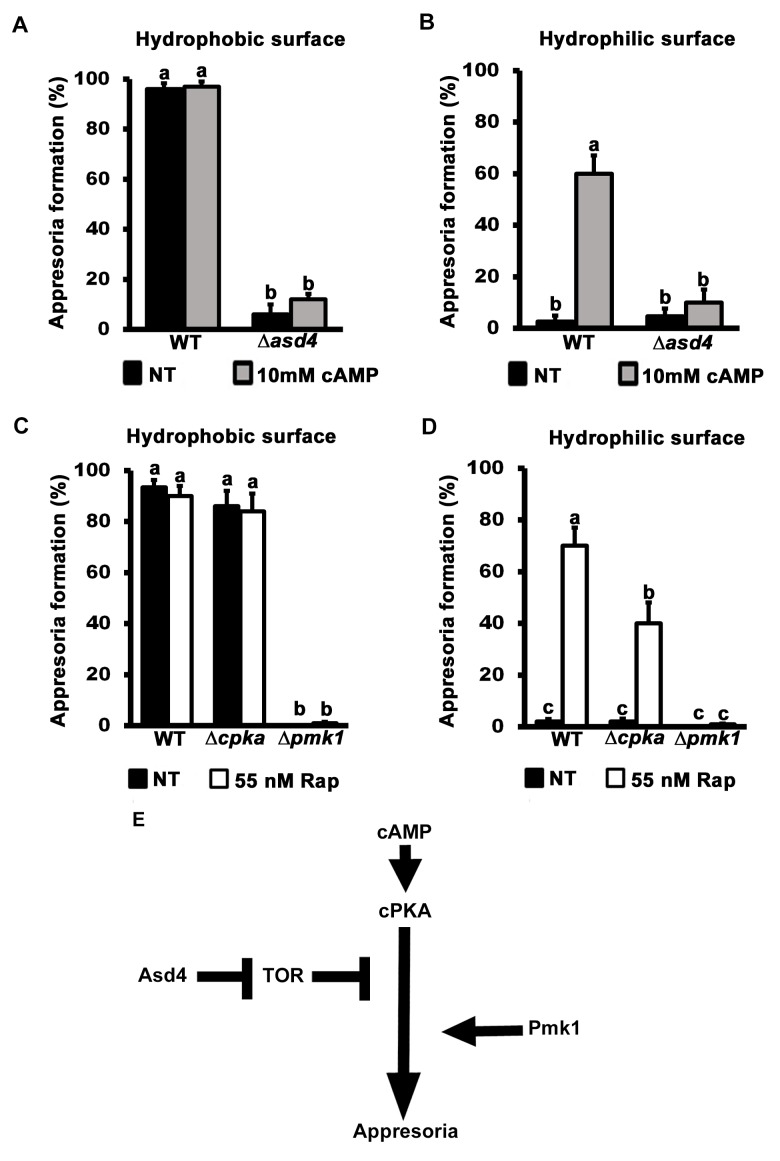

Fig 5. TOR inhibits appressorium formation downstream of cAMP/ PKA signaling.

Treating spore suspensions with 10 mM cAMP did not induce appressorium formation by Δasd4 mutant strains on hydrophobic (A) or (unlike WT) non-inductive hydrophilic surfaces (B). Treatment with 55 nM rapamycin (C and D) induced appressorium formation by Δcpka mutant strains on non-inductive hydrophilic surfaces but did not induce appressorium formation by Δpmk1 mutant strains on any surface. (A-D) Mean appressorial formation rates were determined at 24 hpi from 50 spores per hydrophilic slide or hydrophobic coverslip, repeated in triplicate. NT = no treatment. Error bars are the standard deviation. Bars with different letters are significantly different (Student’s t-test p ≤ 0.05). (E) Appressorium formation requires functional cAMP/ PKA- and MAP kinase-signaling pathways, and Asd4-dependent inactivation of TOR downstream of cPKA.

Further evidence that TOR acts downstream of cPKA is shown in Fig 5C and 5D. Spores of the cAMP/ PKA signaling mutant Δcpka and the MAP kinase mutant Δpmk1 were treated with rapamycin. In common with previous reports [15], by 24 hpi, Δcpka mutant strains had formed appressoria on inductive hydrophobic surfaces at the same rate as WT (Fig 5C). On non-inductive hydrophilic surfaces, Δcpka spores treated with rapamycin formed significantly more (Student’s t-test p ≤ 0.05) appressoria than untreated spores (Fig 5D). In contrast, appressorium formation by Δpmk1 strains was not induced by rapamycin treatment on hydrophobic (Fig 5C) or hydrophilic (Fig 5D) surfaces. Thus, inactivating TOR promotes appressorium formation in a cPKA-independent, Pmk1-dependent manner.

Treatment with cAMP results in germ tube tip differentiation in Δpmk1 strains [16] resulting in hooking and swelling but not appressorium formation S6B Fig). This places Pmk1 function downstream of cAMP/ PKA [16]. In contrast, Δasd4 mutant strains treated with 10 mM cAMP on hydrophilic surfaces did not exhibit hooking or swelling and the germ tube tips remained undifferentiated (S6B Fig). This places Asd4 function upstream of Pmk1.

Together, these results are consistent with the model shown in Fig 5E which shows that appressorium formation requires both activation of the cAMP/ PKA and MAP kinase signaling pathways and inactivation of the TOR signaling pathway, the latter via Asd4-dependent glutamine metabolism. Conversely, activated TOR in Δasd4 strains inhibits appressorium formation downstream of cAMP/ PKA but upstream of Pmk1 (Fig 5E).

Δasd4 appressoria resulting from rapamycin treatment or GLN1 deletion were not infection-competent

We next sought to determine the physiological relevance of the connection between Asd4 and TOR under infection conditions. Δasd4 spores that had been treated with rapamycin and applied to detached rice leaf sheath surfaces formed melanized appressoria (Fig 6A) at rates that were not significantly different to rapamycin treated WT spores (p = 0.08; Fig 6B). However, the resulting Δasd4 appressoria were non-functional and unable to penetrate rice leaf surfaces (Fig 6C and 6D). Similarly, untreated spores of the Δasd4 Δgln1 double mutant, compared to WT and the Δasd4 parental strain, formed appressoria on leaf sheaths (Fig 6E), but none were observed penetrating the host leaf surface (Fig 6D and 6F). These results provide evidence that, on the one hand, Asd4-dependent TOR inactivation is required for appressorium formation during rice infection. On the other hand, Asd4 is shown here to have roles in the pre-penetration stage of infection that might be independent of TOR and which are currently unknown.

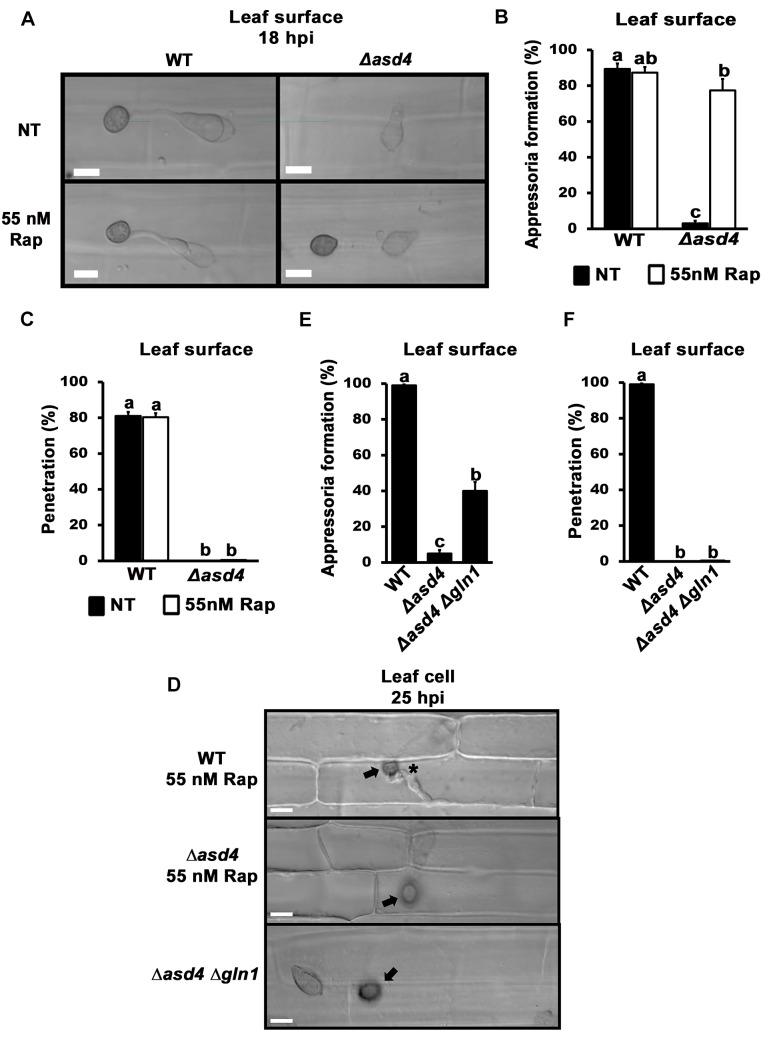

Fig 6. Δasd4 mutant strains treated with rapamycin or lacking GLN1 formed melanized appressoria on rice leaf surfaces that were not infection-competent.

Rapamycin treated spores of Δasd4 mutant strains formed melanized appressoria at 18 hpi on detached leaf sheath surfaces of the susceptible rice cultivar CO-39 (A) at rates that were not different to WT (B). However, the resulting Δasd4 appressoria were non-functional and had not penetrated the leaf cuticle (C), or (D) produced primary hyphae in the rice cell (indicated by the asterisk for WT), by 25 hpi. Arrows indicate appressoria on the surface of the leaf. (E) Like rapamycin treatment, deleting GLN1 in Δasd4 mutant strains also promoted appressorium formation on detached leaf surfaces by 18 hpi, but these Δasd4 Δgln1 appressoria were non-functional and, unlike WT, had not penetrated the leaf surface by 25 hpi (D, F). (B, E) Values are the average number of appressoria formed from 50 spores per rice leaf sheath, repeated in triplicate. (C, F) Mean penetration rates were calculated from 50 appressoria per leaf sheath, repeated in triplicate. Error bars are the standard deviation. Bars with different letters are significantly different (Student’s t-test p ≤ 0.05).

Discussion

New insights into the molecular pathways that regulate plant invasion by pests could reveal attractive targets for effectively managing a range of diseases. Many fungal pathogens rely on appressoria to infect host cells [2], and appressorial developmental, at least in M. oryzae, is dependent on positive-acting cAMP/ PKA- and MAP kinase-signaling pathways [5, 10]. Here, we undertook the first steps in providing a mechanistic account of a negative-acting regulator of appressorium formation in M. oryzae. Appressoria form under nutrient-free, hydrophobic conditions, and we showed here that an activated TOR signaling pathway blocks this process. TOR signaling was found to be constitutively active in the GATA factor mutant strain Δasd4, and characterizing Asd4 function provided several unique insights into the biology of infection-related development. Our results are consistent with a model whereby Asd4 represses the expression of a glutamine synthetase orthologue, GLN1, and down-regulates the expression of other structural genes involved in nitrogen assimilation and glutamine turnover. We propose this maintains intracellular glutamine pools at levels that are not sufficient to activate TOR. Perturbing glutaminolysis and activating GLN1 expression in Δasd4 mutant strains affected the intracellular steady-state pools of glutamine and activated TOR, resulting in inhibition of the cAMP/ PKA signaling pathway and loss of appressorium formation. Inactivating TOR restored appressorium formation by Δasd4 mutant strains. This was most evident on host leaf surfaces where Δasd4 appressoria formed at rates indistinguishable from WT after rapamycin treatment. When taken together, the key novel features of the work described here include elucidating a role for TOR in inhibiting appressorial formation; discovering TOR inactivation requires Asd4; and identifying TOR as a regulator of cAMP/ PKA signaling downstream of cPKA but upstream of its connection with the MAP kinase pathway.

In yeast, the GATA transcription factors Gln3 and Gat1 are required for utilizing non-preferred nitrogen sources and are downstream targets of TOR [20, 41]. TOR is activated in response to carbon and nitrogen sufficiency cues, including glutamine [20, 28, 29, 42], leading to the induction of anabolic processes and growth. Under these conditions, Gln3 and Gat1 are maintained in the cytoplasm. TOR inactivation due to nutrient limitation results in increased autophagy, reduced protein synthesis and increased nitrogen catabolic gene expression following Gln3 and Gat1 nuclear localization [20, 28, 29, 43]. Thus, TOR controls Gln3 and Gat1 activity in yeast. In addition to the Gln3 and Gat1 transcriptional activators, Dal80 and Gzf3 are yeast GATA factors that, like Asd4, act as transcriptional repressors [42]. However, in contrast to the situation described here (whereby Asd4 is upstream of TOR and mediates its activity by controlling glutamine metabolism), no comparable roles in controlling TOR signaling have been described for the yeast Dal80 and Gzf3 GATA factors [20, 44]. Moreover, GATA factors were not found in a recent screen of yeast genes necessary for TOR inactivation [44]. Thus, Asd4 is revealed here as a novel TOR regulator, but whether this role is conserved in other fungi, or necessitated in M. oryzae due to specific demands for TOR-related processes during the infection cycle, is not known.

This work has provided new mechanistic insights into the control of TOR during the M. oryzae-rice interaction. In general, though, the role of TOR in phytopathology is not well understood, although nonselective macroautophagy- an output of inactive TOR signaling in yeast—is necessary for the maturation of incipient appressoria in M. oryzae [45]. Evidence of a role for TOR in root colonization by M. oryzae has also been presented [36] whereby TOR signaling is downregulated in the non-pathogenic RNA processing mutant Δrbp35. In the wheat pathogen F. graminearum, loss of FgFKBP12 and mutations in FgTOR1 abolished the toxicity of rapamycin, while downstream components of the TOR pathway—FgSit4, FgPpg and FgTip41—were shown to have roles in virulence, development and mycotoxin production [35]. A separate study has characterized the serine/threonine-protein kinase SCH9, an important downstream target of yeast TORC1, in F. graminearum and M. oryzae [46]. ΔFgsch9 deletions strains were impaired for conidiation, mycotoxin production and virulence on wheat heads, and produced smaller spores than the F. graminearum parental strain. ΔMosch9 mutant strains exhibited reduced conidia and appressorial sizes than WT and were defective, though not abolished, in plant infection [46]. Recently, we have shown how the biotrophic growth of M. oryzae in rice cells requires a transketolase—dependent metabolic checkpoint involving the activation of TOR [38]. Loss of transketolase function resulted in Δtkl1 mutant strains that formed functional appressoria, penetrated the rice cuticle and elaborated invasive hyphae. However, Δtkl1 strains were depleted for ATP, an agonist of TOR, and these strains underwent mitotic delay and reduced hyphal growth in rice cells due to the inactivation of TOR [38]. How TOR controls the cell cycle during M. oryzae biotrophy is not known. Thus, extending these observations on the roles of TOR signaling during plant pathogenesis, and integrating them into testable models of phytopathogen growth and development, will be a future challenge.

Our results presented here indicate how nitrogen turnover is an important feature of appressorial morphogenesis. Because appressoria develop on the nutrient-free surface of the leaf, internal nitrogen sources that contribute to the glutamine pools affecting TOR must be generated from the recycling of endogenous proteins during autophagic cell death of the spore. This would be consistent with previous work that determined ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis was required for many aspects of M. oryzae development, including appressorium function [47]. How protein turnover during appressorium formation integrates with Asd4-dependent nitrogen assimilation, glutaminolysis and TOR activity is therefore an important question for rice blast research that could shed light on the relationships between GATA and TOR in different systems.

Downstream of Asd4, how the TOR pathway intersects and inhibits the cAMP/ PKA signaling pathway is not known. In yeast, controversy has developed regarding how TOR and PKA signaling pathways regulate common protein targets, with some models suggesting the pathways act in parallel, and some models suggesting TOR is upstream of PKA [48]. Both models are likely valid because recent work has shown that the regulatory subunit of PKA can be a direct target of TOR in yeast, although PKA phosphorylation by TOR occurs selectively and is not global [48]. Our study of M. oryzae places TOR downstream and inhibitory to cAMP/ PKA signaling during appressorium formation and thus provides an opportunity to uncover new relationships between these two fundamental pathways. This would include identifying common targets that control appressorium formation. One point of shared control for the two pathways could be autophagy because Δcpka and Δpmk1 mutants are unable to undergo autophagy in M. oryzae [39], and PKA is necessary for autophagy in yeast [49]. Thus, focusing on TOR, PKA and autophagy will likely yield important insights into appressorial biology.

Another important area of future study will be uncovering the role of Asd4 in cuticle penetration. Although Δasd4 Δgln1 strains and Δasd4 spores treated with rapamycin could form melanized, mature appressoria, they were unable to form penetration pegs. This suggests Asd4 might play a TOR-independent role in the late stages of appressorium maturation and/ or the regulation of penetration peg formation. Successful peg penetration is dependent on the Pmk1 MAP kinase target Mst12 [9, 50], and on NADPH oxidase-dependent control of septin and F-actin reorganization [51]. Also, in addition to the Pmk1 MAP kinase pathway that is essential for appressorium formation, another MAP kinase pathway in M. oryzae, involving Mps1, is not involved in appressorium formation but is required for penetration [52]. Determining if and how Asd4 intersects with these processes will likely yield important new discoveries about appressorium function.

In summary, this work demonstrates the utility of performing axenic physiological analyses to make testable inferences regarding the metabolic strategies underlying M. oryzae infection of host plants. This has revealed that TOR inactivation requires Asd4, and that the TOR pathway is a previously unknown negative-acting regulator of cAMP/ PKA signaling. The results presented here thus provide mechanistic insights that extend our basic knowledge of regulatory networks in fungi by revealing novel connections between GATA-, TOR- and PKA-mediated signaling within the context of appressorium morphogenesis. Given the wealth of knowledge about the role of TOR in yeast physiology and human pathologies, further explorations of the function of TOR in M. oryzae and other appressorium-forming phytopathogens could provide new tools and avenues for alleviating the global burden of plant diseases attributable to fungi. Conversely, revealing Asd4 as a new TOR regulator might shed light on aspects of developmental control that could be applicable to a wide range of cellular processes across taxa.

Materials and Methods

Strains and physiological tests

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 2. Strains were grown on complete medium (CM) containing 1% (W/V) glucose, 0.2% (W/V) peptone, 0.1% (W/V) yeast extract and 0.1% (W/V) casamino acids, or on minimal medium (MM) containing 1% glucose and 0.6% sodium nitrate, unless otherwise stated, as described in [18]. For the growth tests, nitrogen sources were used in MM at 10 mM concentrations, unless otherwise specified. Plate images were taken with a Sony Cyber-shot digital camera, 14.1 mega pixels. For spore counts, 10 mm2 blocks of mycelium were transferred to the center of each plate, and the strains grown for 12 days at 26 °C with 12 hr light/dark cycles. Spores were harvested in sterile distilled water, vortexed vigorously and counted on a haemocytometer (Corning). Spores were counted independently at least three times.

Table 2. Magnaporthe oryzae strains used in this study.

| Strains | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Guy11 | M. oryzae wild type isolate (WT) used throughout this study unless otherwise specified. | [18] |

| Δasd4 | GATA factor (MGG_06050) deletion mutant of Guy11 and used throughout this study unless otherwise specified. | [18] |

| Δasd4 ASD4 GFP | Asd4 complementation strain expressing the Asd4::GFP fusion protein under its native promoter in the Δasd4 mutant background. | This study |

| Δgln1 | Glutamine synthetase (MGG_06888) deletion mutant of Guy11. | This study |

| Δasd4 Δgln1 | Glutamine synthetase (MGG_06888) deletion mutant of Δasd4. | This study |

| Δpmk1 | Map-kinase deletion mutant of Guy11. | [16] |

| Δcpka | cAMP dependent kinase A deletion mutant of Guy11. | [15] |

| Δfpr1 | FKBP12 (MGG_06035) deletion mutant of Guy11. | This study |

| Δrbp35 | RNA-binding protein (MGG_02741) deletion mutant of Guy11. | [36] |

| Δasd4 Δrbp35 | GATA factor (MGG_06050) deletion mutant in the Δrbp35 mutant background. | This study |

| 70–15 | M. oryzae wild type isolate. | [23] |

| Δasd4 [70–15] | GATA factor (MGG_06050) deletion mutant of 70–15. | This study |

The spore suspensions were adjusted to a concentration of 1 x 105 spores/ml to perform the appressoria formation tests. Rapamycin (Rap; LC Laboratories, USA) and monobutyryl cyclic AMP (cAMP; Sigma-Aldritch, USA) were added to the spore suspensions at a concentration of 55 nM and 10 mM, respectively. Appressorial development was evaluated on inductive, hydrophobic plastic coverslips and non-inductive, hydrophilic glass slides. Both substrates were inoculated with 200 μl of each spore suspension and appressoria were observed 24 hrs post-inoculation (hpi). Rates were determined by counting the number of appressoria formed from 50 conidia per coverslip, repeated in triplicate for each strain [53]. Concentrations of 55 nM—1 μM rapamycin could induce appressorial formation of WT on hydrophilic surfaces.

Plant infection assays and live-cell imaging

Rice plant infections were made using a susceptible rice (Oryza sativa) cultivar, CO-39, as described previously [18]. Fungal spores were isolated from 12–14 day-old plate cultures and spray-inoculated onto rice plants of cultivar CO-39 in 0.2% gelatin at a concentration of 1 x 105 spores/ml, and disease symptoms were allowed to develop under conditions of high relative humidity for 120 hrs.

Live-cell imaging was performed as described previously [53] using 3 cm-long leaf sheath segments from 3–4 week-old rice plants and injecting one end of the sheath with a spore suspension of 1 x 105 spores/ml in 0.2% gelatin. At the time points indicated, leaf sheaths were trimmed and observed using a Nikon Eclipse 50i microscope and a Nikon D100 digital net camera. The average rates of appressorium formation and penetration were determined for each strain, in triplicate, by analyzing 50 spores or appressoria per rice cuticle [53].

Asd4GFP was imaged as described previously for H1:RFP [38] using 488 nm and 500–550 nm for excitation and emission wavelengths, respectively.

Genetic manipulations

Gene functional analysis was achieved by the split marker method described in [18], using the oligonucleotide primers shown in S4 Table. GLN1 was replaced in the Δasd4 parental strain using the hygromycin B resistance selectable marker, hph. MoFPR1 and GLN1 were replaced in the Guy11 genome using the ILV1 gene conferring resistance to sulphonyl urea [18]. ASD4 was deleted from the 70–15 background using ILV1. ASD4 was deleted in the Δrbp35 parental strain using the Bar gene conferring bialaphos resistance [18]. Gene deletions were verified by PCR as described previously [18]. The original Δasd4 mutant strain [18] was complemented with ASD4 GFP under its native promoter, constructed using the vector pDL2 and the primers ASD4-G F/R (S4 Table), following the protocol of Zhou et al. [54].

Gene transcript analysis

Strains were grown for 48 h in CM before switching to minimal media for 3 h and 16 h, as indicated. For in planta expression studies, detached rice leaf sheaths were inoculated with WT and harvested at the indicated timepoints. Mycelia and leaves were frozen in liquid nitrogen, and lyophilized for 36 hrs. RNA was extracted from fungal mycelium using the RNeasy mini kit from Qiagen. RNA was converted to cDNA using the qScript reagents from Quantas. Real time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed on an Eppendorf Mastercycler Realplex using the recommended reagents with primers designed using the netprimer software program (S4 Table). qPCR data was analyzed using the Realplex software. Thermocycler conditions were: 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 63°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 30 sec.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP was performed as described in [55]. WT and Δasd4 ASD4 GFP complementation strains were grown in liquid CM for 48 h before switching to 1% GMM with 10 mM NH4 + for 16 h. Three biological replicates were performed per strain. Thirty per cent of each DNA aliquot was saved prior to ChIP and served as the input controls. Anti-GFP mAB-Agarose (D125-8, MBL) was used to precipitate Asd4GFP-bound chromatin. A control ChIP was run in parallel using Mouse IgG-Agarose (A0919, Sigma). The quantification of input and precipitated GLN1 DNA was performed at least in triplicate using qPCR and the specific GLN1 primers shown in S4 Table. GLN1 DNA enrichment by Asd4GFP ChIP was confirmed by calculating the values of GLN1 DNA obtained following Anti-GFP immunoprecipitation (the signal) relative to the levels of GLN1 in the input controls, then comparing the GLN1 signal-to-input ratio derived from the Δasd4 ASD4 GFP samples against those of the WT negative control lacking Asd4GFP.

Amino acid quantification

Amino acid analysis was performed by LC-MS/MS using the aTRAQ kit provided by ABSciex (Framingham, MA). Samples of lyophilized ground mycelia were first washed with water by suspension and centrifugation at 4 oC. The supernatants were aspirated and the pellets were used for extraction. The extractions were performed using 90% MeOH with 128 μM Norleucine added as internal standard. After incubation at -55 oC, a 10 μL aliquot was removed and concentrated by SpeedVac Centrifugation followed by derivatization according to the aTRAQ protocol. The parameters for the MRM acquisition, chromatography and ion source operation were also according to the aTRAQ protocol (Curtain gas = 20, CAD = Medium, IS = 1500; TEM = 600, GS1 = GS2 = 60, heater on) employing a Nova Pak C-18 4 μm 3.9x150mm from Waters Corp. (Milford, MA) for the separation of the tagged amino acids with a sample injection volume of 2 μL. Amino acid concentrations were calculated from the ratio of areas (Heavy aTRAQ/light aTRAQ labeled standards) and corrected for losses for the entire procedure by means of the Nle Internal Standard area recovery.

Supporting Information

(A) Deleting ASD4 from the genome of the wild type isolate 70–15, like deleting ASD4 in the Guy11 background, resulted in Δasd4 (70–15) mutant strains that were reduced in radial growth after 10 days on GMM with 10 mM NH4 + compared to the 70–15 parental strain. Error bars are standard deviation. Bars with different letters are significantly different (Student’s t-test p ≤ 0.05). (B) Conidia of the parental strain 70–15 and the Δasd4 (70–15) mutant strain were applied to artificial hydrophobic surfaces. At 24 hpi, spores of 70–15 had germinated and formed melanized appressoria at the germ-tube tips (red arrow). In contrast, Δasd4 mutant spores (like those of Δasd4 in the Guy11 background) had germinated but failed to develop appressoria by 24 hpi. (C) Complementing the Δasd4 mutant strain derived from Guy11 with a copy of ASD4 fused to GFP and expressed under its native promoter resulted in Δasd4 ASD4 GFP complementation strains that were restored for appressoria formation (red arrows) on artificial hydrophobic surfaces at 24 hpi. (D) The GATA transcription factor Asd4 fused to GFP localizes to the nucleus during appressoria development on artificial hydrophobic surfaces. Scale bar is 10 μm.

(TIF)

GLN1, GLN2, GDH1, GLT1, and MGD1 gene expression was analyzed in strains of WT and Δasd4 after 3 h and 16 h growth in 1% (w/v) glucose MM (GMM) with 10 mM NH4 + as the sole nitrogen source. Results were normalized against the expression of the β-tubulin gene TUB2. Values are the average of three results from at least two independent biological replicates. Error bars are standard deviation.

(TIF)

(A) Mining the genome-wide transcriptional profiling data generated by the Talbot group using RNAseq and High-Throughput SuperSage analysis [27]—available at http://cogeme.ex.ac.uk/supersage/ - reveals how GLN2, GLT1 and MGD1 were expressed during appressorium development but GLN1 and GDH1 expression was not detectable. (B) In planta quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis of gene expression, using cDNAs obtained from rice leaf sheaths of the susceptible rice cultivar CO-39 inoculated with WT, shows GLN1 expression was not detected during M. oryzae infection. Leaf sheaths were inoculated with 1 x 105 spores mL-1. RNA was extracted for cDNA synthesis and gene expression analysis at the indicated time points. Results were normalized against the expression of the M. oryzae actin-encoding gene MoACT1 and are the average of three independent replications. Error bars are standard deviation. Hpi = hours post inoculation. (C) GLN1 gene expression was analyzed in WT and Δasd4 mutant strains after 16 h growth in 1% (w/v) glucose MM (GMM) containing the indicated concentrations of sole nitrogen sources. GLN1 expression following growth in MM containing glutamine as a sole carbon and nitrogen source was also examined. Gene expression results were normalized against expression of the β-tubulin gene (β-TUB2). Values are the average of three replicates. Error bars are standard deviation.

(TIF)

(A) Disrupting GLN1 in Guy11 does not affect colony morphology on complete media. Strains were grown for 10 days. (B) Δgln1 mutant strains were not affected in sporulation after 12 days growth on complete media. (C) Δgln1 mutant strains formed appressoria at the same rate as WT on hydrophobic artificial surface. Values are the average of the number of appressoria formed at 24 hpi from 50 spores per coverslip, repeated in triplicate. (D) Δgln1 mutant strains were fully pathogenic. Strains were inoculated onto rice (CO-39) at a rate of 1x105 spores mL-1. (E) Δasd4 and Δasd4 Δgln1 mutant strains were reduced in radial growth compared to WT after 10 days on GMM with 10 mM NH4 +. (B-C) Error bars are standard deviation. Bars with different letters are significantly different (Student’s t-test p ≤ 0.05).

(TIF)

Δasd4 mutant strains in the 70–15 parental strain background formed appressoria at 24 hpi on artificial hydrophobic surfaces (coverlips) following treatment with 55 nM rapamycin. Bars with different letters are significantly different (Student’s t-test p ≤ 0.05). Values are the average of the number of appressoria formed at 24 hpi from 50 spores per coverslip, repeated in triplicate. NT = no treatment.

(TIF)

(A) Asd4 acts downstream but independently of cAMP/ PKA signaling. Unlike Δasd4, Δcpka mutant strains were not significantly reduced in growth on GMM with 10 mM NH4 +, indicating Asd4 is not under cAMP/ PKA signaling control. (B) Asd4 regulates appressorium formation upstream of Pmk1. Treatment with 10 mM cAMP resulted in appressorium formation by WT on hydrophilic surfaces. Δpmk1 strains responded to cAMP by differentiating germ tube tips on hydrophilic surfaces that hooked and swelled but did not form appressoria, indicating Pmk1 functions downstream of cAMP/PKA signaling [16]. Δasd4 mutant strains did not respond to cAMP treatment on hydrophilic surfaces and their germ tube tips did not differentiate, indicating Asd4 functions upstream of Pmk1. Appressoria are denoted by black arrow. Red arrow denotes differentiated germ tube tips that do not progress beyond hooking and swelling. Bar is 10 μm. Images were made at 24 hpi. NT = no treatment.

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank Janet D. Wright, Department of Plant Pathology, UNL, and Christian Elowsky, Morrison Microscopy Core Research Facility, UNL, for technical assistance. Dr. Javier Seravalli at the Spectroscopy and Biophysics Core Facility, Redox Biology Center, UNL, performed metabolite analyses. We thank Dr. Diane Saunders, John Innes Centre, UK, for critiquing the manuscript. We thank Prof. Nicholas J. Talbot, University of Exeter, UK, for the gift of the strains Δcpka and Δpmk1. We thank Dr. Ane Sesma, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Spain, for the gift of the Δrbp35 mutant strain.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation (IOS-1145347). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Emmett RW, Parbery DG. Appressoria. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1975; 13: 147–65. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dean RA. Signal pathways and appressorium morphogenesis. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1997; 35: 211–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dagdas YF, Yoshino K, Dagdas G, Ryder LS, Bielska E, Steinberg G, et al. Septin-mediated plant cell invasion by the rice blast fungus, Magnaporthe oryzae . Science. 2012; 336:1590–5. 10.1126/science.1222934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mendgen K, Hahn M, Deising H. Morphogenesis and mechanisms of penetration by plant pathogenic fungi. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1996; 34:367–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilson RA, Talbot NJ. Under pressure: Investigating the biology of plant infection by Magnaporthe oryzae . Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009; 7:185–95. 10.1038/nrmicro2032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yi M, Valent B. Communication between filamentous pathogens and plants at the biotrophic interface. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2013; 51: 587–611. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-172916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O'Connell RJ, Thon MR, Hacquard S, Amyotte SG, Kleemann J, Torres MF, et al. Lifestyle transitions in plant pathogenic Colletotrichum fungi deciphered by genome and transcriptome analyses. Nat Genet. 2012; 44: 1060–5. 10.1038/ng.2372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Talbot NJ. On the trail of a cereal killer: Exploring the biology of Magnaporthe grisea . Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003; 57:177–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li G, Zhou X, Xu JR. Genetic control of infection-related development in Magnaporthe oryzae . Curr Opin Microbiol. 2012; 15: 678–84. 10.1016/j.mib.2012.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fernandez J, Wilson RA. Cells in cells: morphogenetic and metabolic strategies conditioning rice infection by the blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae . Protoplasma. 2014; 251: 37–47. 10.1007/s00709-013-0541-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fernandez J, Marroquin-Guzman M, Wilson RA. Mechanisms of Nutrient Acquisition and Utilization During Fungal Infections of Leaves. Ann Rev Phytopathol. 2014; 52: 155–74. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-102313-050135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee YH, Dean RA. cAMP regulates infection structure formation in the plant pathogenic fungus Magnaporthe grisea . Plant Cell. 1993; 5:693–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jelitto TC, Page HA, Read ND. Role of external signals in regulating the pre-penetration phase of infection by the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea . Planta. 1994; 194: 471–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adachi K, Hamer JE. Divergent cAMP signaling pathways regulate growth and pathogenesis in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea . Plant Cell. 1998; 10: 1361–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xu JR, Urban M, Sweigard JA, Hamer JE. The CPKA gene of Magnaporthe grisea is essential for appressorial penetration. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1997; 10:187–94. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xu JR, Hamer JE. MAP-kinase and cAMP signaling regulate infection structure formation and pathogenic growth in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea . Genes Dev. 1996; 10, 2696–2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Saunders DG, Dagdas YF, Talbot NJ. Spatial un-coupling of mitosis and cytokinesis during appressorium- mediated plant infection by the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae . Plant Cell. 2010; 22: 2417–28. 10.1105/tpc.110.074492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wilson RA, Gibson RP, Quispe CF, Littlechild JA, Talbot NJ. An NADPH-dependent genetic switch regulates plant infection by the rice blast fungus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010; 107: 21902–7. 10.1073/pnas.1006839107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wilson RA, Arst HN Jr. Mutational analysis of AREA, a transcriptional activator mediating nitrogen metabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans and a member of the "streetwise" GATA family of transcription factors. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998; 62: 586–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Loewith R, Hall MN. Target of rapamycin (TOR) in nutrient signaling and growth control. Genetics. 2011; 189:1177–1201. 10.1534/genetics.111.133363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fernandez J, Wright JD, Hartline D, Quispe CF, Madayiputhiya N, Wilson RA. Principles of carbon catabolite repression in the rice blast fungus: Tps1, Nmr1-3, and a MATE–Family Pump regulate glucose metabolism during Infection. PLoS Genet. 2012; 8: e1002673 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fernandez J, Wilson RA. Why no feeding frenzy? Mechanisms of nutrient acquisition and utilization during Infection by the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae . Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2012; 25: 1286–93. 10.1094/MPMI-12-11-0326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dean RA, Talbot NJ, Ebbole DJ, Farman ML, Mitchell TK, Orbach MJ, et al. The genome sequence of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea . Nature. 2005; 434: 980–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mora J. Glutamine metabolism and cycling in Neurospora crassa . Microbiol Rev. 1990; 54: 293–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yan D. Protection of the glutamate pool concentration in enteric bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007; 104: 9475–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Le A, Lane AN, Hamaker M, Bose S, Gouw A, Barbi J, et al. Glucose-independent glutamine metabolism via TCA cycling for proliferation and survival in B cells. Cell Metab. 2012; 15:110–121. 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Soanes DM, Chakrabarti A, Paszkiewicz KH, Dawe AL, Talbot NJ. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of appressorium development by the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae . PLoS Pathog. 2012; 8:e1002514 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Crespo JL, Powers T, Fowler B, Hall MN. The TOR-controlled transcription activators GLN3, RTG1, and RTG3 are regulated in response to intracellular levels of glutamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002; 99:6784–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Crespo JL, Hall MN. Elucidating TOR signaling and rapamycin action: lessons from Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002; 66:579–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gallinetti J, Harputlugil E, Mitchell JR. Amino acid sensing in dietary-restriction-mediated longevity: roles of signal-transducing kinases GCN2 and TOR. Biochem J. 2013; 449:1–10. 10.1042/BJ20121098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peng T, Golub TR, Sabatini DM. The immunosuppressant rapamycin mimics a starvation-like signal distinct from amino acid and glucose deprivation. Mol Cell Biol. 2002; 22: 5575–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Barbet NC, Schneider U, Helliwell SB, Stansfield I, Tuite MF, Hall MN. TOR controls translation initiation and early G1 progression in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1996; 7: 25–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Heitman J, Movva NR, Hall M. Targets for cell cycle arrest by the immunosuppresant rapamycin in yeast. Science. 1991; 253: 905–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gamboa- Melendez H, Billon-Grand G, Fevre M, Mey G. Role of the Botrytis cinerea FKBP12 ortholog in pathogenic development and in sulfur regulation. Fung Genet Biol. 2009; 46: 308–20. 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yu F, Gu Q, Yun Y, Yin Y, Xu JR, Shim WB, et al. The TOR signaling pathway regulates vegetative development and virulence in Fusarium graminearum . New Phytol. 2014; 203:219–32. 10.1111/nph.12776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Franceschetti M, Bueno E, Wilson RA, Tucker SL, Gomez-Mena C, Calder G, et al. Fungal virulence and development is regulated by alternative pre-mRNA 3′ end processing in Magnaporthe oryzae . PLoS Pathog. 2011; 7:e1002441 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rodriguez-Romero J, Franceschetti M, Bueno E, Sesma A. Multilayer Regulatory Mechanisms Control Cleavage Factor I Proteins in Filamentous Fungi. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; (43): 179–95. 10.1093/nar/gku1297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fernandez J, Marroquin-Guzman M, Wilson RA. Evidence for a transketolase-mediated metabolic checkpoint governing biotrophic growth in rice cells by the blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae . PLOS Pathogens 2014; 10 (9): e10004354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Veneault-Fourrey C, Barooah M, Egan M, Wakley G, Talbot NJ. Autophagic fungal cell death is necessary for infection by the rice blast fungus. Science. 2006; 312: 580–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Diaz-Troya S, Perez-Perez ME, Florencio FJ, Crespo JL. The role of TOR in autophagy regulation from yeast to plants and mammals. Autophagy. 2008; 4: 851–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Beck T, Hall MN. The TOR signaling pathway controls nuclear localization of nutrient-regulated transcription factors. Nature. 1999; 402:689–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Georis I, Feller A, Tate JJ, Cooper TG, Dubois E. Nitrogen catabolite repression-sensitive transcription as a readout of Tor pathway regulation: the genetic background, reporter gene and GATA factor assayed determine the outcomes. Genetics. 2009; 181:861–74. 10.1534/genetics.108.099051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Powers RW III, Kaeberlein M, Caldwell SD, Kennedy BK, Fields S. Extension of chronological life span in yeast by decreased TOR pathway signaling. Genes Dev. 2006; 20:174–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Neklesa TK, Davis RW. A Genome-Wide Screen for Regulators of TORC1 in Response to Amino Acid Starvation Reveals a Conserved Npr2/3 Complex. PLoS Genet. 2009; 5: e1000515 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kershaw MJ, Talbot NJ. Genome-wide functional analysis reveals that infection-associated fungal autophagy is necessary for rice blast disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009; 106: 15967–72 10.1073/pnas.0901477106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chen D, Wang Y, Zhou X, Wang Y, Xu J-R. The Sch9 Kinase Regulates Conidium Size, Stress Responses, and Pathogenesis in Fusarium graminearum . PLoS ONE. 2014; 9(8): e105811 10.1371/journal.pone.0105811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Oh Y, Franck WL, Han S, Shows A, Gokce E, Meng S, et al. Polyubiquitin is required for growth, development and pathogenicity in the Rice Blast Fungus Magnaporthe oryzae . PLoS One. 2012; 7: e42868 10.1371/journal.pone.0042868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Soulard A, Cremonesi A, Moes S, Schütz F, Jenö P, Hall MN. The rapamycin-sensitive phosphoproteome reveals that TOR controls protein kinase A toward some but not all substrates. Mol Biol Cell. 2010; 21: 3475–86. 10.1091/mbc.E10-03-0182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stephan JS, Yeh YY, Ramachandran V, Deminoff SJ, Herman PK. The Tor and PKA signaling pathways independently target the Atg1/Atg13 protein kinase complex to control autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009; 106:17049–54. 10.1073/pnas.0903316106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Park G, Xue C, Zheng L, Lam S, Xu JR. MST12 regulates infectious growth but not appressorium formation in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea . Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2002; 15:183–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ryder LS, Dagdas YF, Mentlak TA, Kershaw MJ, Thornton CR, Schuster M, et al. NADPH oxidases regulate septin-mediated cytoskeletal remodeling during plant infection by the rice blast fungus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013; 110:3179–84. 10.1073/pnas.1217470110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Xu JR, Staiger CJ, Hamer JE. Inactivation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase Mps1 from the rice blast fungus prevents penetration of host cells but allows activation of plant defense responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998; 95:12713–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fernandez J, Yang KT, Cornwell KM, Wright JD, Wilson RA. Growth in rice cells requires de novo purine biosynthesis by the blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae . Sci Rep. 2013; 3:2398 10.1038/srep02398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhou X, Li G, Xu JR. Efficient approaches for generating GFP fusion and epitope-tagging constructs in filamentous fungi. Methods Mol Biol. 2011; 722: 199–212. 10.1007/978-1-61779-040-9_15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fernandez J, Marroquin-Guzman M, Nandakumar R, Shijo S, Cornwell K, Li G, et al. Plant defense suppression is mediated by a fungal sirtuin during rice infection by Magnaporthe oryzae . Mol Micro. 2014; 94: 70–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) Deleting ASD4 from the genome of the wild type isolate 70–15, like deleting ASD4 in the Guy11 background, resulted in Δasd4 (70–15) mutant strains that were reduced in radial growth after 10 days on GMM with 10 mM NH4 + compared to the 70–15 parental strain. Error bars are standard deviation. Bars with different letters are significantly different (Student’s t-test p ≤ 0.05). (B) Conidia of the parental strain 70–15 and the Δasd4 (70–15) mutant strain were applied to artificial hydrophobic surfaces. At 24 hpi, spores of 70–15 had germinated and formed melanized appressoria at the germ-tube tips (red arrow). In contrast, Δasd4 mutant spores (like those of Δasd4 in the Guy11 background) had germinated but failed to develop appressoria by 24 hpi. (C) Complementing the Δasd4 mutant strain derived from Guy11 with a copy of ASD4 fused to GFP and expressed under its native promoter resulted in Δasd4 ASD4 GFP complementation strains that were restored for appressoria formation (red arrows) on artificial hydrophobic surfaces at 24 hpi. (D) The GATA transcription factor Asd4 fused to GFP localizes to the nucleus during appressoria development on artificial hydrophobic surfaces. Scale bar is 10 μm.

(TIF)

GLN1, GLN2, GDH1, GLT1, and MGD1 gene expression was analyzed in strains of WT and Δasd4 after 3 h and 16 h growth in 1% (w/v) glucose MM (GMM) with 10 mM NH4 + as the sole nitrogen source. Results were normalized against the expression of the β-tubulin gene TUB2. Values are the average of three results from at least two independent biological replicates. Error bars are standard deviation.

(TIF)

(A) Mining the genome-wide transcriptional profiling data generated by the Talbot group using RNAseq and High-Throughput SuperSage analysis [27]—available at http://cogeme.ex.ac.uk/supersage/ - reveals how GLN2, GLT1 and MGD1 were expressed during appressorium development but GLN1 and GDH1 expression was not detectable. (B) In planta quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis of gene expression, using cDNAs obtained from rice leaf sheaths of the susceptible rice cultivar CO-39 inoculated with WT, shows GLN1 expression was not detected during M. oryzae infection. Leaf sheaths were inoculated with 1 x 105 spores mL-1. RNA was extracted for cDNA synthesis and gene expression analysis at the indicated time points. Results were normalized against the expression of the M. oryzae actin-encoding gene MoACT1 and are the average of three independent replications. Error bars are standard deviation. Hpi = hours post inoculation. (C) GLN1 gene expression was analyzed in WT and Δasd4 mutant strains after 16 h growth in 1% (w/v) glucose MM (GMM) containing the indicated concentrations of sole nitrogen sources. GLN1 expression following growth in MM containing glutamine as a sole carbon and nitrogen source was also examined. Gene expression results were normalized against expression of the β-tubulin gene (β-TUB2). Values are the average of three replicates. Error bars are standard deviation.

(TIF)

(A) Disrupting GLN1 in Guy11 does not affect colony morphology on complete media. Strains were grown for 10 days. (B) Δgln1 mutant strains were not affected in sporulation after 12 days growth on complete media. (C) Δgln1 mutant strains formed appressoria at the same rate as WT on hydrophobic artificial surface. Values are the average of the number of appressoria formed at 24 hpi from 50 spores per coverslip, repeated in triplicate. (D) Δgln1 mutant strains were fully pathogenic. Strains were inoculated onto rice (CO-39) at a rate of 1x105 spores mL-1. (E) Δasd4 and Δasd4 Δgln1 mutant strains were reduced in radial growth compared to WT after 10 days on GMM with 10 mM NH4 +. (B-C) Error bars are standard deviation. Bars with different letters are significantly different (Student’s t-test p ≤ 0.05).

(TIF)

Δasd4 mutant strains in the 70–15 parental strain background formed appressoria at 24 hpi on artificial hydrophobic surfaces (coverlips) following treatment with 55 nM rapamycin. Bars with different letters are significantly different (Student’s t-test p ≤ 0.05). Values are the average of the number of appressoria formed at 24 hpi from 50 spores per coverslip, repeated in triplicate. NT = no treatment.

(TIF)

(A) Asd4 acts downstream but independently of cAMP/ PKA signaling. Unlike Δasd4, Δcpka mutant strains were not significantly reduced in growth on GMM with 10 mM NH4 +, indicating Asd4 is not under cAMP/ PKA signaling control. (B) Asd4 regulates appressorium formation upstream of Pmk1. Treatment with 10 mM cAMP resulted in appressorium formation by WT on hydrophilic surfaces. Δpmk1 strains responded to cAMP by differentiating germ tube tips on hydrophilic surfaces that hooked and swelled but did not form appressoria, indicating Pmk1 functions downstream of cAMP/PKA signaling [16]. Δasd4 mutant strains did not respond to cAMP treatment on hydrophilic surfaces and their germ tube tips did not differentiate, indicating Asd4 functions upstream of Pmk1. Appressoria are denoted by black arrow. Red arrow denotes differentiated germ tube tips that do not progress beyond hooking and swelling. Bar is 10 μm. Images were made at 24 hpi. NT = no treatment.

(TIF)