Abstract

Premise of the study:

Targeted sequencing using next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms offers enormous potential for plant systematics by enabling economical acquisition of multilocus data sets that can resolve difficult phylogenetic problems. However, because discovery of single-copy nuclear (SCN) loci from NGS data requires both bioinformatics skills and access to high-performance computing resources, the application of NGS data has been limited.

Methods and Results:

We developed MarkerMiner 1.0, a fully automated, open-access bioinformatic workflow and application for discovery of SCN loci in angiosperms. Our new tool identified as many as 1993 SCN loci from transcriptomic data sampled as part of four independent test cases representing marker development projects at different phylogenetic scales.

Conclusions:

MarkerMiner is an easy-to-use and effective tool for discovery of putative SCN loci. It can be run locally or via the Web, and its tabular and alignment outputs facilitate efficient downstream assessments of phylogenetic utility, locus selection, intron-exon boundary prediction, and primer or probe development.

Keywords: data mining, introns, marker development, next-generation sequencing, phylogenetics, single-copy nuclear genes, transcriptomes

The availability of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies and improved computational tools has revolutionized the field of plant molecular systematics (reviewed in Cronn et al., 2012; McCormack et al., 2013; Soltis et al., 2013). Access to genome-scale data presents exciting opportunities for researchers to develop hundreds or potentially thousands of informative, taxon-specific loci from nuclear genomes—large, multilocus data sets that can potentially resolve relationships at any phylogenetic scale (e.g., Godden et al., 2012).

Recently, there has been much interest in developing single-copy nuclear (SCN) loci from new or existing NGS resources such as transcriptomes (i.e., sequences representing the expressed portion of the genome; see Bräutigam and Gowik, 2010; Strickler et al., 2012) or genome skimming data (i.e., low-coverage genome sequencing; see Straub et al., 2012), and a few pioneering studies have reported great success in developing large sets of orthologous SCN loci with elaborately designed bioinformatic pipelines (e.g., Straub et al., 2011; Rothfels et al., 2013; Weitemier et al., 2014; Tonnabel et al., 2014; Pillon et al., 2014). Nevertheless, SCN locus discovery from NGS data remains a complex process for many researchers with limited bioinformatics training and access to computational resources. To address these challenges, we developed MarkerMiner 1.0, a fully automated, open-access bioinformatic workflow to aid plant researchers in the discovery of putative orthologous SCN loci and to facilitate downstream marker development activities such as primer or probe design with user-friendly output.

METHODS AND RESULTS

Overall design of the application

Transcriptome sequencing is a useful approach for acquiring new data for phylogenetic marker development, and it might offer some advantages over genome skimming approaches. For example, the high output of NGS platforms, coupled with the reduced representation afforded by transcriptome sequencing, permits multiplexing of more samples from a clade of interest. This provides a more comprehensive a priori survey of phylogenetic utility across both gene space and the clade of interest than genome skimming on a fixed budget. Moreover, researchers may find that expressed sequence tags (ESTs) or de novo transcriptome assemblies already exist for many groups of angiosperms (e.g., transcriptomes available through the 1000 Plants [oneKP] project; see www.onekp.com for more information), and use of these existing data resources can eliminate or reduce the overall costs and time investment for some marker discovery projects.

MarkerMiner is a novel, command line–based computational workflow that identifies putative orthologous SCN loci present in two or more user-provided angiosperm transcriptome assemblies and outputs detailed tabular results and sequence alignments for downstream assessment of phylogenetic utility, locus selection, intron-exon boundary prediction, and primer or probe development for targeted sequencing (see Figs. 1–3) . The tool features a user-configurable command line interface that is backed by a computational pipeline, and its job submission graphical user interface is accessible to researchers with limited bioinformatics training. Moreover, MarkerMiner is freely available via the iPlant cloud computing infrastructure (http://www.iplantcollaborative.org/ci/atmosphere; Goff et al., 2011 [also available at https://bitbucket.org/srikarchamala/markerminer]), providing a working solution for researchers with limited or no access to high-performance computing resources.

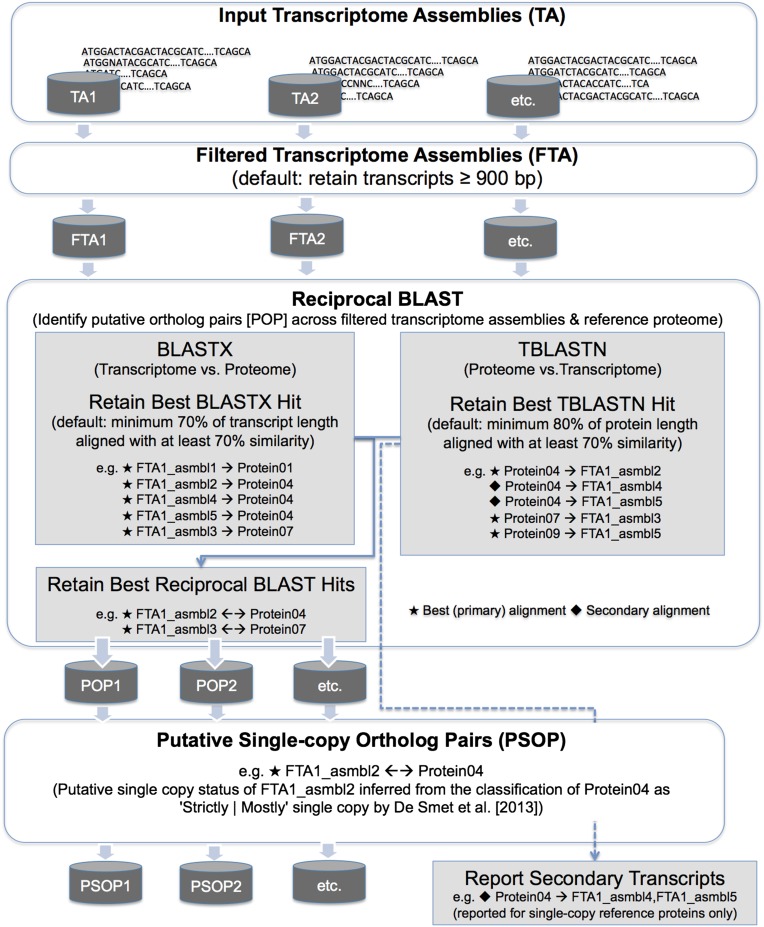

Fig. 1.

Filtering steps performed by MarkerMiner 1.0 to identify single-copy nuclear genes from angiosperm transcriptome assembly input. Best (primary) alignments are identified with a star, and secondary alignments are identified with a diamond.

Fig. 3.

Alignment output produced by MarkerMiner 1.0, including multiple sequence alignments and reference CDS profile alignments for single-copy nuclear loci. The alignment output is useful for assessing the phylogenetic utility of individual loci, predicting putative intron sizes and locations, and developing primers or probes for targeted sequencing.

MarkerMiner’s fully automated workflow (Figs. 1 and 2) is implemented in Python and makes use of specific open-source bioinformatic software to perform the following data filtering and processing steps: transcript length filtering, putative ortholog filtering, putative SCN locus filtering, secondary transcript reporting, transcript clustering and reorientation, DNA multiple sequence alignments, and DNA profile alignments with protein-coding reference sequences (CDS) containing masked introns. The tool offers convenient functions with regard to user-specified filtering parameters and reference CDS, and these are described in more detail below.

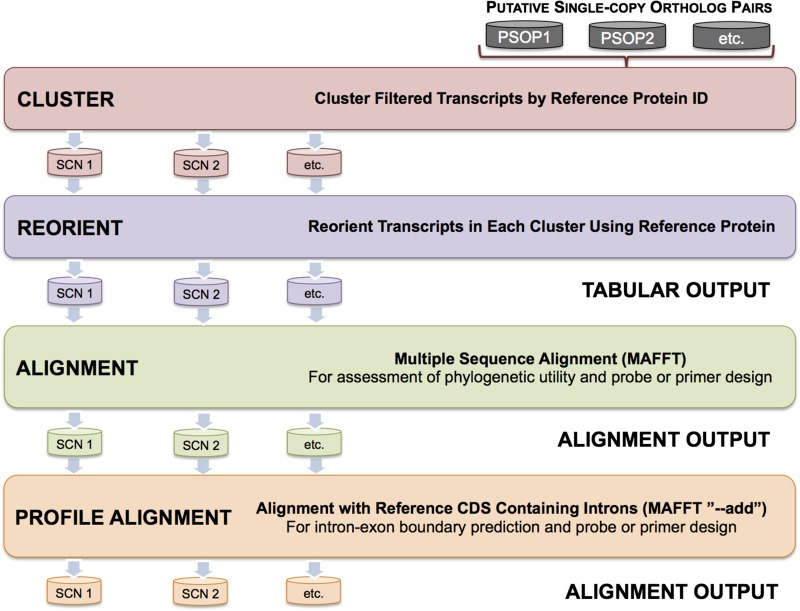

Fig. 2.

Additional data processing and output steps performed by MarkerMiner 1.0.

Filtering transcriptomes using minimum length parameters

As a first step, MarkerMiner filters each user-provided transcriptome assembly using a minimum length parameter. By default, the application removes transcripts less than 900 bp. However, users have the flexibility to specify an alternative length parameter based on their individual preferences and research needs. Decreasing the default length parameter (e.g., <900 bp) will facilitate retention of larger numbers of transcripts for downstream filtering steps. In contrast, increasing the default length parameter (e.g., >900 bp) may result in discovery of fewer orthologs between sampled taxa.

Filtering putative ortholog pairs with reciprocal BLAST queries

MarkerMiner employs independent reciprocal BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990, 1997) queries on each filtered transcriptome assembly to identify putative orthologs. By default, the application uses the Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. proteome from the PLAZA 2.5 database (Van Bel et al., 2012) as a reference. However, we offer the flexibility to use one of 15 additional reference options (see Box 1), and MarkerMiner is updated periodically as new references become available. Under the default settings, the filtered transcripts from each assembly are aligned against Arabidopsis proteins with NCBI-BLASTX using E-value 0.01 and, conversely, the Arabidopsis proteins are aligned against the filtered transcripts from each assembly with TBLASTN using E-value 0.01. The reciprocal top hits from each of the BLAST analyses are retained if they meet the following criteria, respectively: a minimum of 70% of the transcript length is aligned with a reference protein with at least 70% sequence similarity (BLASTX), and a minimum of 80% of the protein length is aligned to a transcript with at least 70% sequence similarity (TBLASTN). These stringency criteria for parsing BLAST output are default parameters, but users have the option to specify alternative criteria.

Box 1. Reference options available in MarkerMiner 1.0. The default option is indicated with an asterisk (*). Reference genomes and their corresponding annotations were downloaded from the PLAZA 2.5 database (Van Bel et al., 2012).

Arabidopsis lyrata (L.) O’Kane & Al-Shehbaz

Arabidopsis thaliana L.*

Brachypodium distachyon (L.) P. Beauv.

Carica papaya L.

Fragaria vesca L.

Glycine max (L.) Merr.

Malus domestica Borkh.

Manihot esculenta Crantz

Medicago truncatula Gaertn.

Oryza sativa L.

Populus trichocarpa Torr. & A. Gray

Ricinus communis L.

Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench

Theobroma cacao L.

Vitis vinifera L.

Zea mays L.

Filtering putative single-copy nuclear genes

De Smet et al. (2013) reported a carefully curated list of SCN genes as part of a gene family analysis that included 17 genomes broadly distributed across angiosperm phylogeny (i.e., five monocots and 12 eudicots). Of the SCN genes identified by the study, 177 were “strictly single-copy” in all 17 genomes, and 2809 were “mostly single-copy” (i.e., single-copy in most of the genomes, with duplicates detected in at least one to as many as three other genomes) (De Smet et al., 2013). As the evolution of these SCN genes is largely uninfluenced by gene duplication, their sequence evolution is expected to act in concordance with species evolution, making them an invaluable resource in mining for SCN loci from transcriptomes.

MarkerMiner employs a user-specified SCN gene reference set curated by DeSmet et al. (2013) as a final data filter. Putative ortholog pairs whose transcripts have top reciprocal BLAST hits against SCN reference proteins are retained and classified as putative single-copy ortholog pairs.

Secondary transcript reporting

There may be cases in which a single-copy protein has more than one transcript passing the BLAST filtering criteria. However, as previously indicated, only the transcript with the top scoring alignment is reported by MarkerMiner as a putatively orthologous single-copy transcript. For some researchers, information about additional transcripts with lower scores (which also align uniquely to a single-copy protein) may be of particular interest. These “secondary transcripts” may represent splice isoforms, putative paralogs, or partially assembled transcripts, although their characterization is difficult in the absence of a reference genome.

MarkerMiner provides additional information about secondary transcripts via additional output. Users can use these tabular results to guide decisions about which loci to pursue for downstream marker development or to investigate further the duplication status of secondary transcripts for particular genes of interest.

Clustering, reorientation, and alignment of single-copy transcripts and output

After the transcripts corresponding to SCN loci are filtered from all assemblies, MarkerMiner clusters transcripts by reference protein ID (Fig. 2). The transcripts within each of the resulting SCN gene clusters (or orthogroup sets) are reverse-complemented as necessary to ensure identical sequence orientation prior to multiple sequence alignment; the corresponding DNA reference sequence of A. thaliana (or an alternative, user-specified reference) is used to reorient sequences. Next, MarkerMiner outputs a detailed tabular report that includes the following details for each SCN locus detected: a reference gene ID, a single-copy classification (e.g., “strictly” or “mostly”) according to De Smet at al. (2013), a gene functional description, the number of putative orthologs detected across all assemblies, and a scaffold ID for each of the transcriptome assemblies included in the analysis (Fig. 2; see also the user manual [available at https://bitbucket.org/srikarchamala/markerminer], for example). All gene functional descriptions reported to users by MarkerMiner correspond to the TAIR10 Arabidopsis genome release (Lamesch et al., 2012).

MarkerMiner outputs two types of alignments to aid researchers with downstream assessments of phylogenetic utility, locus selection, intron-exon boundary prediction, and primer or probe development. First, a multiple sequence alignment is performed for each gene cluster with MAFFT (Katoh et al., 2002, 2009) using −quiet and −auto parameters, and alignment files are reported in FASTA format (Figs. 2 and 3). Users can edit these alignments, assess phylogenetic utility among detected loci, infer preliminary phylogenies (if appropriate), or proceed with downstream development of individual loci for phylogenetic applications (Figs. 2 and 3). Second, MarkerMiner aligns the user-specified reference CDS with intronic regions masked with the character ‘N’ to their respective MAFFT multiple sequence alignments (Fig. 3) by using MAFFT’s ‘−add’ functionality (Katoh and Frith, 2012); the intron coordinates correspond to data extracted from the PLAZA 2.5 database.

MarkerMiner provides all alignment output in FASTA format. The alignments can be useful for prediction of putative intron-exon boundaries and approximate intron size, which will facilitate design of primers or probes for amplification or capture of complete or partial intronic regions. For example, intronic regions can be recovered completely using exon-anchored primer pairs and PCR amplification (Lemmon and Lemmon, 2013; Pillon et al., 2014). Alternatively, intronic regions can also be recovered with hybrid enrichment approaches (e.g., sequence capture; see Lemmon and Lemmon, 2013), whereby probes are designed in the flanking exonic regions of targeted introns (e.g., close to the intron-exon junction). These probes will facilitate capture of partial or complete intronic regions along with their exonic counterparts during a hybridization step, followed by PCR enrichment and sequencing on NGS platforms. With current sequencing technologies capable of generating read lengths up to 2 × 300 bp (Illumina MiSeq; see http://www.illumina.com/systems/sequencing.html), sequencing of flanking intronic regions captured or amplified by exonic probes or primers is becoming straightforward. The use of MarkerMiner to develop intronic markers will therefore enable greater use of intron regions for phylogenetic applications.

Many of the SCN loci identified by De Smet et al. (2013) correspond to “housekeeping” genes. Due to their wide conservation across eukaryotes, the exonic regions of these genes may offer limited utility at shallow phylogenetic scales (Calonje et al., 2009). Fast-evolving intronic regions may represent more desirable choices for phylogenetic studies of closely related, recently derived, and rapidly diverging angiosperm lineages (see Godden et al., 2012). MarkerMiner’s intron-exon boundary predictions are based on a user-specified reference CDS; the accuracy of intron-exon boundaries and intron sizes will depend on the level of divergence between the user-specified reference and the taxa under study.

Accessibility and high-performance computing

MarkerMiner is open-source and is made freely accessible to the research community for use in a local computing environment as well as via the iPlant Collaborative Atmosphere cloud-computing infrastructure (http://www.iplantcollaborative.org/ci/atmosphere; Goff et al., 2011 [also available at https://bitbucket.org/srikarchamala/markerminer]). Dedicated instances based on a preconfigured MarkerMiner machine image can be requisitioned on iPlant for an analysis and terminated once the workflow is completed. Apart from providing command-line access, each instance also exposes a lightweight Web application with a graphical user interface that can be used to configure and invoke the workflow with the desired input files and job parameters. A user manual for the web application and instructions to access an example data set are provided at https://bitbucket.org/srikarchamala/markerminer.

Tests of MarkerMiner using oneKP transcriptomes

We evaluated the performance of MarkerMiner and tested its efficacy for SCN locus discovery with four data sets comprising transcriptome assemblies from the oneKP project: Lamiales (n = 77), Amaryllidaceae s.l. (n = 7), Draba L. (n = 6), and Solanum L. (n = 6) (see Appendix 1 for a list of samples). The selected data sets represent groups broadly distributed across angiosperm phylogeny (e.g., asterids, rosids, and monocots sensu APG III [2009]) and actual marker development projects (or test cases) focused on resolving relationships at different phylogenetic scales (e.g., interfamilial [Lamiales], intrafamilial [Amaryllidaceae s.l.], and intrageneric [Draba and Solanum]).

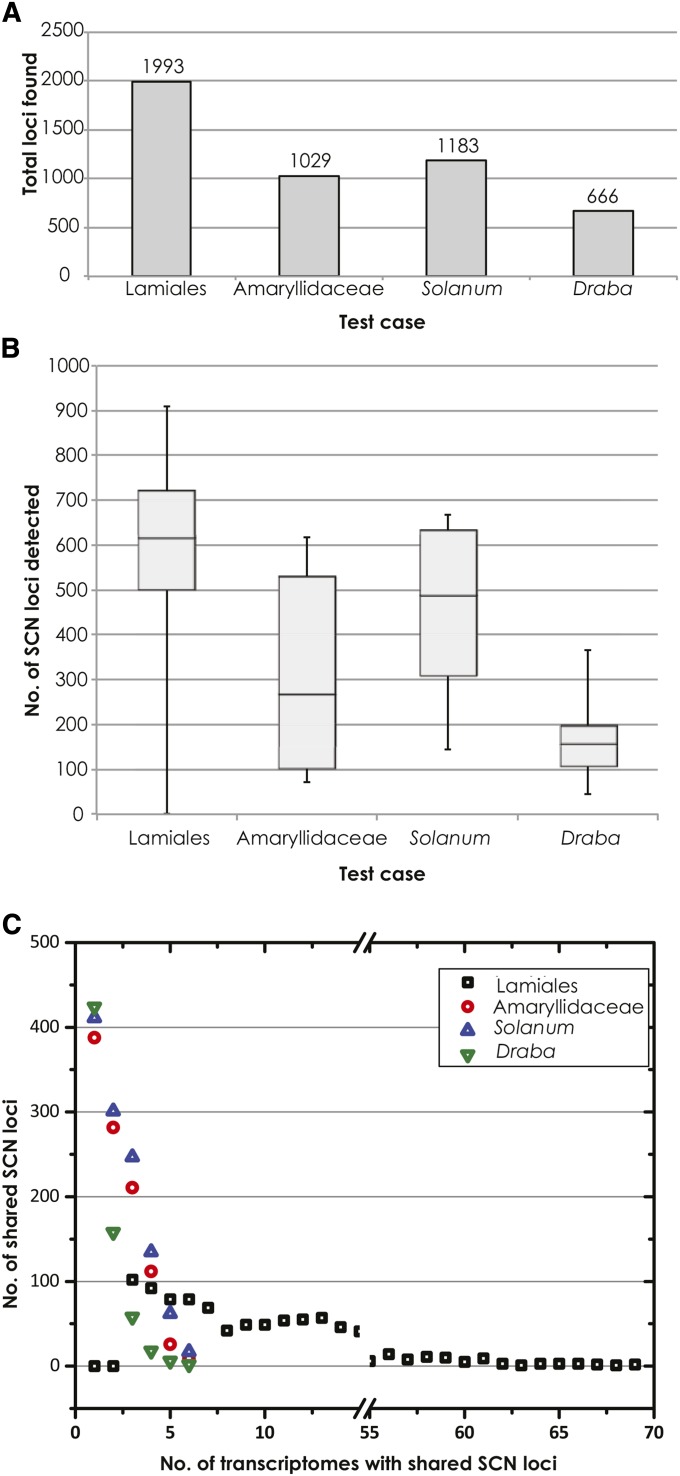

The total number of distinct, putative SCN loci detected by MarkerMiner (Fig. 4A) for each clade ranged from 666 (Draba) to 1993 (Lamiales) (mean = 1217, median = 1106, standard deviation = 560), with a mean of 535 loci detected per transcriptome accession across the four test cases (median = 584, standard deviation = 226, range = 0–909; results for individual data sets are reported in Fig. 4B). The distribution of shared SCN loci identified across all sampled accessions within each of the four test cases showed a negative trend (Fig. 4C); few loci were shared by all accessions, and most loci were detected in only one to three accessions. Nevertheless, at least 13% (Solanum) to 22% (Lamiales and Draba) of the SCN loci were shared by at least half of the sampled accessions in each test case (mean = 18%, median = 18%, and standard deviation = 0.05% across all four test cases), providing adequate data for downstream assessments of phylogenetic utility and primer or probe development.

Fig. 4.

MarkerMiner 1.0 results for four test cases involving SCN locus discovery at different phylogenetic scales: e.g., interfamilial (Lamiales: 77 transcriptomes), intrafamilial (Amaryllidaceae s.l.: 7 transcriptomes), and intergeneric (Solanum L. and Draba L.: 6 transcriptomes each). Three graphs illustrate the following for each of the test cases: (A) the total number of detected SCN loci, (B) the distribution of SCN loci detected per taxon, and (C) the distribution of shared SCN loci detected across sampled accessions.

The phylogenetic utility of putative single-copy genes amplified using primers developed via a preliminary version of MarkerMiner (developed by S. Chamala) was documented in Metrosideros Banks ex Gaertn. (Pillon et al., 2014). Intron regions were amplified by designing primers on flanking exons using putative intron-exon boundary information determined by aligning cDNA sequences with those of Arabidopsis genes.

Researchers should be aware that loci detected by MarkerMiner might not be single-copy in their clade of study. Evaluation of the single-copy status of genes is needed within the clade of interest, for example using phylogenetic (e.g., Pillon et al., 2013) or other (e.g., Duarte et al., 2010) approaches.

CONCLUSIONS

MarkerMiner, as demonstrated by our tests with oneKP data, represents an easy-to-use and effective tool for phylogenetic marker development. Researchers with limited bioinformatics training and limited access to high-performance computing resources can use MarkerMiner to identify hundreds of putative SCN genes for phylogenomic analyses of any angiosperm group of interest. While we acknowledge that transcriptomic approaches to marker development may result in large numbers of missing loci across the surveyed samples (as demonstrated by each of our four test cases with oneKP data), the cautionary emphasis placed on individual gene absences may be overstated. First, most of the putative single-copy genes detected by MarkerMiner have general “housekeeping” functions (Duarte et al., 2010; De Smet et al., 2013). Thus, individual gene absences across surveyed transcriptomes are more likely to represent differences in sequencing quality and coverage across samples than actual gene losses. These differences can be mitigated with careful sample preparation and planning of marker development projects involving NGS (e.g., standardized tissue collection practices and realistic limits to multiplexing). Second, our MarkerMiner results indicated that a large proportion of the putative SCN loci are generally shared by at least half of the surveyed transcriptomes. Despite missing data across our oneKP transcriptomes, MarkerMiner was able to recover ample data for assessments of phylogenetic utility and downstream marker development applications with as few as six transcriptomes.

The downstream processes for selecting and developing markers for targeted sequencing are more or less the same for approaches that use either transcriptomic or genome skimming data, with the caveat that the phylogenetic utility of noncoding loci cannot be assessed a priori from transcriptome data. Nevertheless, as suggested by our results, transcriptomic approaches using MarkerMiner are both economical and efficient, and MarkerMiner’s multipurpose output can facilitate marker development projects targeting coding and noncoding regions.

Appendix 1.

Transcriptome assemblies from the 1000 Plants (oneKP) project used for the development and testing of MarkerMiner 1.0. Four test cases are shown: (1) Amaryllidaceae s.l., (2) Lamiales (including outgroups from Boraginales, Gentianales, and Solanales), (3) Draba, and (4) Solanum.

| APG III clade | Order | Family | Taxon | oneKP sample ID |

| Amaryllidaceae s.l. | ||||

| Monocots | Asparagales | Amaryllidaceae s.l. | Allium sativum L. | GJPF |

| Monocots | Asparagales | Amaryllidaceae s.l. | Agapanthus africanus (L.) Hoffmanns. | PRFO |

| Monocots | Asparagales | Amaryllidaceae s.l. | Narcissus viridiflorus Schousb. | IQYY |

| Monocots | Asparagales | Amaryllidaceae s.l. | Phycella cyrtanthoides (Sims) Lindl. | DMIN |

| Monocots | Asparagales | Amaryllidaceae s.l. | Rhodophiala splendens (Renjifo) Traub | JDTY |

| Monocots | Asparagales | Amaryllidaceae s.l. | Traubia modesta (Phil.) Ravenna | ZKPF |

| Monocots | Asparagales | Amaryllidaceae s.l. | Zephyranthes treatiae S. Watson | DPFW |

| Lamiales | ||||

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Boraginales | Boraginaceae | Ehretia acuminata R. Br. | EMAL |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Boraginales | Boraginaceae | Lennoa madreporoides La Llave & Lex. | SMUR |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Boraginales | Boraginaceae | Mertensia paniculata (Aiton) G. Don | DKFZ |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Boraginales | Boraginaceae | Phacelia campanularia A. Gray | YQIJ |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Boraginales | Boraginaceae | Pholisma arenarium Nutt. | HANM |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Gentianales | Gentianaceae | Exacum affine Balf. f. | KPUM |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Gentianales | Rubiaceae | Galium boreale L. | WQRD |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Acanthaceae | Anisacanthus quadrifidus (Vahl) Nees | PCGJ |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Acanthaceae | Ruellia brittoniana Leonard | AYIY |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Acanthaceae | Sanchezia Ruiz & Pav. | NBMW |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Acanthaceae | Strobilanthes dyeriana Mast. | WEAC |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Bignoniaceae | Kigelia africana (Lam.) Benth. | QKEI |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Bignoniaceae | Kigelia africana (Lam.) Benth. | SVQC |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Bignoniaceae | Mansoa alliacea (Lam.) A. H. Gentry | TKEK |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Bignoniaceae | Tabebuia umbellata (Sond.) Sandwith | UTQR |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Byblidaceae | Byblis gigantea Lindl. | GDZS |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Calceolariaceae | Calceolaria pinifolia Cav. | DCCI |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Gesneriaceae | Saintpaulia ionantha H. Wendl. | RWKR |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Gesneriaceae | Sinningia tuberosa (Mart.) H. E. Moore | DTNC |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Gratiolaceae | Bacopa caroliniana (Walter) B. L. Rob. | CLRW |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Agastache rugosa (Fisch. & C. A. Mey.) Kuntze | PUCW |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Ajuga reptans L. | UCNM |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Lavandula angustifolia Mill. | FYUH |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Leonurus japonicus Houtt. | SNNC |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Marrubium vulgare L. | EAAA |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Melissa officinalis L. | TAGM |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Clinopodium serpyllifolium (M. Bieb.) Kuntze subsp. fruticosum (L.) Bräuchler | WHNV |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Nepeta cataria L. | FUMQ |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Oxera neriifolia (Montrouz.) Beauvis. | GNPX |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Oxera pulchella Labill. | RTNA |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Pogostemon cablin (Blanco) Benth. | GETL |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Poliomintha bustamanta B. L. Turner | XMBA |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Prunella vulgaris L. | PHCE |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Pycnanthemum tenuifolium Schrad. | DYFF |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Rosmarinus officinalis L. | FDMM |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Salvia L. | EQDA |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Scutellaria montana Chapm. | ATYL |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Plectranthus scutellarioides (L.) R. Br. | BAHE |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Teucrium chamaedrys L. | LRRR |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lamiaceae | Thymus vulgaris L. | IYDF |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lentibulariaceae | Pinguicula agnata Casper | MXFG |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lentibulariaceae | Pinguicula caudata Schltdl. | JCMU |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Lentibulariaceae | Utricularia L. | HRUR |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Oleaceae | Chionanthus retusus Paxton | KTAR |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Oleaceae | Forestiera segregata (Jacq.) Krug & Urb. | UEEN |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Oleaceae | Ligustrum sinense Lour. | MZLD |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Oleaceae | Olea europaea L. | TORX |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Orobanchaceae | Conopholis americana (L.) Wallr. | FAMO |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Orobanchaceae | Epifagus virginiana (L.) W. P. C. Barton | URZI |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Orobanchaceae | Epifagus virginiana (L.) W. P. C. Barton | XMOG |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Orobanchaceae | Lindenbergia philippinensis Benth. | WUZV |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Orobanchaceae | Lindenbergia philippinensis Benth. | ZVFS |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Orobanchaceae | Orobanche fasciculata Nutt. | PHOQ |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Orobanchaceae | Orobanche fasciculata Nutt. | VTOK |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Paulowniaceae | Paulownia fargesii Franch. | UMUL |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Pedaliaceae | Uncarina grandidieri (Baill.) Stapf | ZRIN |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Plantaginaceae | Antirrhinum majus L. | EBOL |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Plantaginaceae | Antirrhinum majus L. | TPUT |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Plantaginaceae | Antirrhinum braun-blanquetii Rothm. | YRHD |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Plantaginaceae | Digitalis purpurea L. | GNRI |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Plantaginaceae | Plantago maritima L. | YKZB |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Plantaginaceae | Plantago virginica L. | PTBJ |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Rhemanniaceae | Rehmannia glutinosa Steud. | OWAS |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Schlegeliaceae | Schlegelia parasitica (Sw.) Miers ex Griseb. | GAKQ |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Schlegeliaceae | Schlegelia parasitica (Sw.) Miers ex Griseb. | CWLL |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Schlegeliaceae | Schlegelia violacea Griseb. | EDXZ |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Scrophulariaceae | Anticharis glandulosa Asch. | EJBY |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Scrophulariaceae | Buddleja L. | GRFT |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Scrophulariaceae | Buddleja lindleyana Lindl. | XRLM |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Scrophulariaceae | Celsia arcturus Jacq. | SIBR |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Scrophulariaceae | Verbascum L. | XXYA |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Tetrachondraceae | Polypremum procumbens L. | COBX |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Verbenaceae | Lantana camara L. | PSHB |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Verbenaceae | Phyla dulcis (Trevir.) Moldenke | MQIV |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Lamiales | Verbenaceae | Verbena hastata L. | GCFE |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Solanales | Convolvulaceae | Ipomoea pubescens Lam. | EMBR |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Solanales | Solanaceae | Solanum ptychanthum Dunal | DLJZ |

| Draba | ||||

| Core eudicots/rosids/malvids | Brassicales | Brassicaceae | Draba aizoides L. | HABV |

| Core eudicots/rosids/malvids | Brassicales | Brassicaceae | Draba hispida Willd. | GTSV |

| Core eudicots/rosids/malvids | Brassicales | Brassicaceae | Draba magellanica Lam. | UVQL |

| Core eudicots/rosids/malvids | Brassicales | Brassicaceae | Draba oligosperma Hook. | LAPO |

| Core eudicots/rosids/malvids | Brassicales | Brassicaceae | Draba ossetica (Rupr.) Sommier & Levier | LJQF |

| Core eudicots/rosids/malvids | Brassicales | Brassicaceae | Draba sachalinensis Trautv. | BXBF |

| Solanum | ||||

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Solanales | Solanaceae | Solanum cheesmaniae (L. Riley) Fosberg | UGJI |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Solanales | Solanaceae | Solanum dulcamara L. | GHLP |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Solanales | Solanaceae | Solanum lasiophyllum Humb. & Bonpl. ex Dunal | DLAI |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Solanales | Solanaceae | Solanum ptychanthum Dunal | DLJZ |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Solanales | Solanaceae | Solanum sisymbriifolium Lam. | NMDZ |

| Core eudicots/asterids/lamiids | Solanales | Solanaceae | Solanum virginianum L. | LQJY |

LITERATURE CITED

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology 215: 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schäffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D. J. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Research 25: 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APG III. 2009. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 161: 105–121. [Google Scholar]

- Bräutigam A., Gowik U. 2010. What can next generation sequencing do for you? Next generation sequencing as a valuable tool in plant research. Plant Biology 12: 831–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calonje M., Martín-Bravo S., Dobeš C., Gong W., Jordon-Thaden I., Kiefer C., Kiefer M., et al. 2009. Non-coding nuclear DNA markers in phylogenetic reconstruction. Plant Systematics and Evolution 282: 257–280. [Google Scholar]

- Cronn R., Knaus B. J., Liston A., Maughan P. J., Parks M., Syring J. V., Udall J. 2012. Targeted enrichment strategies for next-generation plant biology. American Journal of Botany 99: 291–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smet R., Adams K. L., Vandepoele K., Van Montagu M. C. E., Maere S., Van de Peer Y. 2013. Convergent gene loss following gene and genome duplications creates single-copy families in flowering plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 110: 2898–2903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte J., Wall P. K., Edger P., Landherr L., Ma H., Pires J. C., Leebens-Mack J., dePamphilis C. W. 2010. Identification of shared single copy nuclear genes in Arabidopsis, Populus, Vitis, and Oryza and their phylogenetic utility across various taxonomic levels. BMC Evolutionary Biology 10: 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godden G. T., Jordon-Thaden I. E., Chamala S., Crowl A. A., García N., Germain-Aubrey C. C., Heaney J. M., et al. 2012. Making next-generation sequencing work for you: Approaches and practical considerations for marker development and phylogenetics. Plant Ecology & Diversity 5: 427–450. [Google Scholar]

- Goff S. A., Vaughn M., McKay S., Lyons E., Stapleton A. E., Gessler D., Matasci N., et al. 2011. The iPlant Collaborative: Cyberinfrastructure for plant biology. Frontiers in Plant Science 2: 10.3389/fpls.2011.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Misawa K., Kuma K., Miyata T. 2002. MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Research 30: 3059–3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Asimenos G., Toh H. 2009. Multiple alignment of DNA sequences with MAFFT. In D. Posada [ed.], Methods in molecular biology, vol. 537: Bioinformatics for DNA sequence analysis, 39–64. Humana Press, Totowa, New Jersey, USA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Frith M. C. 2012. Adding unaligned sequences into an existing alignment using MAFFT and LAST. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 28: 3144–3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamesch P., Berardini T. Z., Li D., Swarbreck D., Wilks C., Sasidharan R., Muller R., et al. 2012. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): Improved gene annotation and new tools. Nucleic Acids Research 40(D1): D1202–D1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon E. M., Lemmon A. R. 2013. High-throughput genomic data in systematics and phylogenetics. Annual Review of Ecology Evolution and Systematics 44: 99–121. [Google Scholar]

- McCormack J. E., Hird S. M., Zellmer A. J., Carstens B. C., Brumfield R. T. 2013. Applications of next-generation sequencing to phylogeography and phylogenetics. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 66: 526–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillon Y., Johansen J., Sakishima T., Chamala S., Barbazuk W. B., Stacy E. A. 2013. Primers for low-copy nuclear genes in the Hawaiian endemic Clermontia (Campanulaceae) and cross-amplification in Lobelioideae. Applications in Plant Sciences 1(6): 1200450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillon Y., Johansen J., Sakishima T., Chamala S., Barbazuk W. B., Stacy E. A. 2014. Primers for low-copy nuclear genes in Metrosideros and cross-amplification in Myrtaceae. Applications in Plant Sciences 2(10): 1400049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothfels C. J., Larsson A., Li F.-W., Sigel E. M., Huiet L., Burge D. O., Ruhsam M., et al. 2013. Transcriptome-mining for single-copy nuclear markers in ferns. PLoS ONE 8: e76957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis D. E., Gitzendanner M. A., Stull G., Chester M., Chanderbali A., Chamala S., Jordon-Thaden I. E., et al. 2013. The potential of genomics in plant systematics. Taxon 62: 886–898. [Google Scholar]

- Straub S. C. K., Fishbein M., Livshultz T., Foster Z., Parks M., Weitemier K., Cronn R. C., Liston A. 2011. Building a model: Developing genomic resources for a common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) with low coverage genome sequencing. BMC Genomics 12: 211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub S. C. K., Parks M., Weitemier K., Fishbein M., Cronn R. C., Liston A. 2012. Navigating the tip of the genomic iceberg: Next-generation sequencing for plant systematics. American Journal of Botany 99: 349–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickler S. R., Bombarely A., Mueller L. A. 2012. Designing a transcriptome next-generation sequencing project for a nonmodel plant species. American Journal of Botany 99: 257–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonnabel J., Olivieri I., Mignot A., Rebelo A., Justy F., Santoni S., Caroli S., et al. 2014. Developing nuclear DNA phylogenetic markers in the angiosperm genus Leucadendron (Proteaceae): A next-generation sequencing transcriptomic approach. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 70: 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bel M., Proost S., Wischnitzki E., Movahedi S., Scheerlinck C., Van de Peer Y., Vandepoele K. 2012. Dissecting plant genomes with the PLAZA comparative genomics platform. Plant Physiology 158: 590–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitemier K., Straub S. C. K., Cronn R. C., Fishbein M., Schmickl R., McDonnell A., Liston A. 2014. Hyb-Seq: Combining target enrichment and genome skimming for plant phylogenomics. Applications in Plant Sciences 2: 1400042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]