Abstract

Background

Celiac disease (CD) is a lifelong disorder. Patients are at increased risk of complications and comorbidity.

Objectives

We conducted a review of the literature on patient support and information in CD and aim to issue recommendations about patient information with regards to CD.

Methods

Data source: We searched PubMed for English-language articles published between 1900 and June 2014, containing terms related to costs, economics of CD, or education and CD.

Study selection: Papers deemed relevant by any of the participating authors were included in the study.

Data synthesis: No quantitative synthesis of data was performed. Instead we formulated a consensus view of the information that should be offered to all patients with CD.

Results

There are few randomized clinical trials examining the effect of patient support in CD. Patients and their families receive information from many sources. It is important that health care personnel guide the patient through the plethora of facts and comments on the Internet. An understanding of CD is likely to improve dietary adherence. Patients should be educated about current knowledge about risk factors for CD, as well as the increased risk of complications. Patients should also be advised to avoid other health hazards, such as smoking. Many patients are eager to learn about future non-dietary treatments of CD. This review also comments on novel therapies but it is important to stress that no such treatment is available at present.

Conclusion

Based on mostly observational data, we suggest that patient support and information should be an integral part of the management of CD, and is likely to affect the outcome of CD.

Keywords: Celiac (American spelling), coeliac (British spelling), gluten-free diet, support

Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) occurs in approximately 1% of the Western population.1 It is triggered by exposure to gluten in susceptible individuals with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DQ2+ or DQ8+.2 While most patients have villous atrophy (VA), minor enteropathy is also compatible with CD,3 and the vast majority of individuals show elevated levels of antibodies against endomysium and tissue transglutaminase.4,5

CD is a lifelong disorder, requiring dietary treatment. It is associated with a number of complications and comorbidities,6 including excess mortality.7 Earlier research has shown that patients with CD perceive their disease and its treatment as a burden.8,9

Considering that some data suggest that one out of four patients with CD is dissatisfied with the information offered by their physician (a smaller proportion reporting dissatisfaction with the information offered by the dietitian),10 and that patient support may have a direct bearing on levels of or likelihood to adhere to a gluten-free diet (GFD),10 we were motivated to review the existing literature relating to patient support in CD.

A secondary aim of this paper was to issue recommendations about patient information with regards to CD.

Methods

This project was initiated by JFL and DS as part of a review on the management of CD supported by the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG). This paper constitutes the background for the shorter text on patient support in our Gut paper on management of CD.11 The task force for the current paper consisted of eight individuals from three countries (Britain: n = 6, Sweden: n = 1, and Italy: n = 1).

We searched PubMed for English-language articles published between 1900 and June 2014, containing terms related to costs, economics of CD, or education and CD (Appendix). We did not specifically search PubMed for the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) term “Diet, Gluten-Free.” Although a GFD is important to the management of CD, its role has been described in detail in our main review on celiac management11 and was not the main topic of the current literature review.

Through the PubMed search for papers on costs and economics of CD, we identified 115 hits (see Appendix for actual search algorithm). Of these, three were classified as randomized clinical trials in PubMed,12–14 but on detailed scrutiny, none of them was actually a randomized clinical trial. Therefore, none of the data on costs and economics in this paper represent grade A evidence.15

The PubMed search for education in CD yielded 291 hits (see Appendix for actual search algorithm), 15 of which were classified as randomized clinical trials in PubMed. On closer examination four studies were true randomized clinical trials and relevant to this literature review.16–19 Given the paucity of randomized clinical trials, no quantitative synthesis of data was performed. Neither did we examine potential bias in the included studies. Instead we formulated a consensus view of the information that should be offered to all patients with CD.

Almost all evidence in this literature review represents grade C or D evidence. We did not specify what items reflect grade C or D, respectively.

No database other than PubMed (such as EMBASE) was searched for the purpose of this study. Neither did we consider unpublished data. For the current literature review, five authors (JFL, PJC, TC, IN and CC) took a greater responsibility and carried out the literature searches and the data collection, while GLS and DSS reviewed the paper and contributed to the intellectual content of the paper. Papers deemed relevant by any of the participating authors were included in the literature review. The literature review was not preceded by any protocol registration.

Finally, when examining Web content that may be of help to support patients with CD, we used Google (June 5, 2014) to search for “celiac OR coeliac” (American and British spelling). This search yielded more than 4 million hits.

Recommendations of this paper are also consistent with our first main review published in Gut, where a synopsis of this paper was published.11 Here we expand and elaborate on patient support in CD. All authors agree with the conclusions of this paper.

Results

General aspects of patient support

Patient support is not a one-way communication but should be a dialogue with the patient and his or her family. Employers may also need information about CD. In pediatric cases, nannies, school nurses, teachers and kitchen staff may require information and education, but not necessarily from health care personnel. To the greatest extent possible, the patient and his or her family should be given the opportunity to actively participate in decisions regarding the care of CD. It is important to assign enough time for providing information and answering questions.

Whenever possible, the first information about CD and treatment with a GFD should be given at time of diagnosis, or shortly thereafter.10 Patient information may improve symptoms in patients with CD. Key points of information for the patient are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key points in information to the patient

| *Patient support involves dialogue and engagement. The patients and their family should be encouraged to actively participate in the care of celiac disease (CD). |

| *CD is a life-long disorder. |

| *Patient societies and support groups can offer support and information. |

| *A gluten-free diet relieves most symptoms, and is likely to offer some protection against certain complications but not all. |

Means of informing patients

Information is usually given orally, but particularly in English-speaking countries a large number of books and booklets aimed at patients with CD are also available.20,21 Increasing access to the Internet means that more and more people learn about CD through peers and non-medical personnel22 rather than exclusively from interaction with health care personnel. In a randomized controlled trial, Sainsbury et al. found that online intervention improved dietary adherence in CD.16

Before the CD diagnosis

Often symptoms and signs lead up to a visit to a physician before the diagnosis is confirmed. Informing the patient about the planned investigation for CD and/or other gastrointestinal disorders can increase the patient’s confidence in health care and strengthen the patient-physician relationship. Patients can be informed about serological testing, but also about HLA-testing, if appropriate (as a means to rule out current or future CD), and of endoscopy with biopsy as the standard means to confirm a CD diagnosis. Pre-procedure concerns are common,23 with one study showing that six out of 10 patients worry before an endoscopy. Worries include finding something that is wrong, but also fear of detecting cancer and of pain during the procedure. Upper endoscopy is generally a safe24 and well-tolerated procedure. Patients may feel some relief knowing that there is no pain from obtaining the tissue from the small intestine. Since many patients receive local anesthesia, it is wise to inform patients that they must inform their doctor of any known allergy to local anesthetic agents, including dentistry anesthesia. After endoscopy, it may take up to weeks to a month before the pathologist has reviewed the slides and can write a definite report regarding the small intestinal appearance.

Finally, patients should be strongly advised not to start a gluten-free diet (GFD) before serological tests or upper endoscopy and biopsy as changes may resolve and give a false-negative result.11

First information about the diagnosis of CD

Patients’ requirements for information may vary at different consultations. Some newly diagnosed patients may have undergone extensive investigations, and some may have had severe disease symptoms for many years. To these patients, a diagnosis of CD can provide relief: “At last someone has found out what was wrong with me” or “I knew there was something wrong with me, this was not just my imagination.” To others, a diagnosis of a life-long disorder can mean shock and disbelief.

In order to establish a positive long-term relationship with the patient, it is important to give the patient ample time for questions and answers. A recent Finnish study suggested10 that many patients were dissatisfied with the amount and the quality of information they get from their physician. Among patients’ complaints were that the physician limits his or her information to “the diagnosis,” or “refers” to the dietitian or to the Internet for further information. Low-quality information is associated with more negative attitudes toward having CD.10 Caregivers should know that the patient’s reaction to the impact of a CD diagnosis might be related to personal resources, for example there is an immediate financial burden associated with purchasing gluten-free products particularly in countries where no financial support is provided to patients with CD. Other possible negative influences may be a significant delay between the beginning of symptoms and diagnosis, type of symptoms, as well as the degree of family support.25–27

What is CD and “where” does it occur?

CD is a chronic, systemic, autoimmune disorder in genetically predisposed individuals. Gluten proteins and related prolamins found in wheat, barley, and rye trigger an autoimmune injury to the gut, skin, liver, joints, uterus, and other organs.28 VA is identified on small-bowel biopsy, which is considered the gold standard for diagnosing this condition. False-negative small-bowel histology can occur because of the patchy nature of small-bowel mucosal changes.28

CD affects on average 1% of individuals in Western Europe.1 The investigation of milder clinical features and use of serology has led to an increased detection rate.29 The age of presentation varies but the frequent age range for presenting adults is between the fourth and sixth decade. Adult presentations of CD are more common than pediatric cases and there are even patients now being recognized and diagnosed who are elderly.30 The classical presentation in children occurs at age under 2 years with symptoms of malabsorption and poor growth.31–33 This typically occurs after introduction of gluten in the diet. There is, however, a trend toward fewer patients presenting with symptomatic CD characterized by diarrhea and a significant shift toward more patients presenting with milder symptoms or as asymptomatic adults detected at screening.34

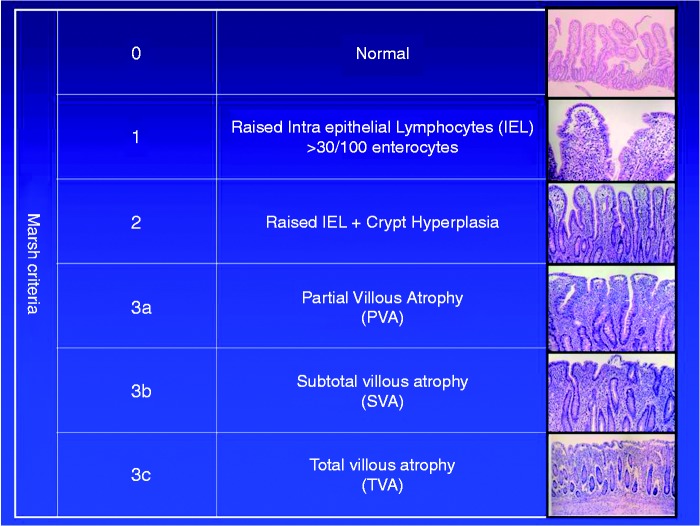

Although we are unaware of any evidence supporting our recommendation, briefly informing the patient about the function of the small intestine is likely to help patients understand their symptoms, as well as the need to adhere to a GFD. This may form a natural starting point in patient education. Showing pictures of normal and abnormal mucosa can help illustrate the detrimental effect that gluten has in patients with CD, but also may show the patient the potential of mucosal healing (by adhering to a GFD). While there is a relative paucity of literature on the long-term effects of mucosal healing in CD35–37 such seems to confer better health in CD,38,39 but not affect overall mortality.40

A picture of VA can be used to illustrate inflammation (Figure 1), but also the impaired uptake of micronutrients (and secondary consequences, including B12 deficiency, anemia and osteoporosis), water (contributing to diarrhea), and sources of energy (lack of energy leading to fatigue; and in children to growth failure).

Figure 1.

Small intestinal mucosa.

The decrease in villous height (and increased crypt depth) in Marsh 3. Showing the patient these figures can help explain concepts such as inflammation and malabsorption.

Etiology of CD

CD is an intestinal disorder with multifactorial etiology. HLA and non-HLA genes together with gluten and possibly additional environmental factors predispose to CD.41 This complex interplay between intrinsic and extrinsic factors produces a range of clinical presentation from asymptomatic individuals to severe malabsorption.42

CD is strongly associated with HLA class II gene (DR3, DR5/DR7 or DR4) known as HLA-DQ2 (>90%) and HLA-DQ843 located on chromosome 6p21.2 These haplotypes bind toxic gluten peptides and are located in antigen-presenting cells (APCs) of the mucosa. The absence of these molecules (DQ2 or DQ8) has a negative predictive value for CD close to 100%,44 i.e. a negative test rules out CD.

Reactive CD4+ T-cells recognize gluten-derived peptides bound to HLA-DQ2//8 on APCs.45 The binding of these peptides to APCs is enhanced by the action of the intracellular and extracellular enzyme transglutaminase (TTG) by selective deamidation of glutamine residues to negatively charged glutamic acid.45,46 Following activation, T-cells release proinflammatory cytokines resulting in an inflammatory cascade, primarily in the upper small intestine, characterized by infiltration of the lamina propria and the epithelium with chronic inflammatory cells and VA.45

An understanding of the basics of genetics underlying CD can allow the patient to understand a) why some people are at risk of CD while others are not; b) that comorbid conditions in CD may occur both before and after diagnosis of CD;47,48 c) and that some comorbid conditions may not be preventable since their increased frequency in celiac patients are due to shared genetics,2,49 and that environmental factors are contributory to the risk of CD but cannot alone explain CD. The latter can alleviate stress in the parents of children with CD, who sometimes accuse themselves of short breast-feeding or otherwise non-optimal infant feeding.

Current research on the role of breast-feeding at time of gluten introduction and the risk of CD is controversial,50–52 and although many pediatricians recommend breast-feeding at the time of gluten introduction, parents should be informed that “lack of breast-feeding” is never the sole reason for developing CD. Parents should be informed that the evidence that infection at time of gluten introduction may trigger CD in the child is limited.53 The role of infection in CD etiology is unclear.54–57 A recent paper found a higher risk of CD in patients with ongoing infection at time of gluten introduction although the risk estimates failed to attain statistical significance.58 Some data also indicate that psychological stress may be involved in the development of CD.59

GFD and dietary adherence

Currently, the GFD constitutes the only available treatment for CD. It is crucial that the patient understands the role of GFD in order to achieve a high dietary adherence.60 Ideally information on GFD should be given in collaboration with a dietitian.10

Although, strong evidence that a GFD protects against all complications and comorbidity in CD is lacking,11,40 it seems clear that patient symptoms improve on a GFD. Patients with newly diagnosed CD often report substantial improvements in symptoms and well-being after starting on a GFD.10 Empirical data strongly suggest that GFD will lead to catch-up growth in children with growth failure at diagnosis.61 Education of the patient should include detailed information about the food to avoid and how to read the labels of processed food. Poor dietary adherence in pregnant women is also likely to influence intrauterine growth of the fetus, since women giving birth before CD diagnosis (but not those giving birth after) suffer an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcome.62,63 Several studies, although none of them attained statistical significance, also suggest that dietary adherence influences the risk of future lymphoma in CD.64 Finally, dietary adherence also seems to have a beneficial effect on bone mineral density in individuals with CD,65 and mucosal healing on control biopsy has been linked to a lower risk of hip fracture.38

Dietary adherence may be especially difficult to achieve in patients diagnosed through screening. From the physician’s perspective, a strict GFD may seem an easy task to pursue, but this may not be the case for many patients. Children and adults with CD report reduced quality of life because of dietetic restrictions.27,66–68 For the physician this situation is difficult also since in the absence of symptoms that can be improved, the benefit of the diet we are recommending must lie in reducing future complications, and as noted above we lack clear evidence of this. Hence in the screen-detected patient we may be proposing dietary restrictions that the patient finds unpleasant without evidence of definite benefit. Nevertheless, despite the limited literature in this field, some investigators suggest that screen-detected CD patients may still derive symptomatic benefit.69–71

Figures on the adherence to GFD are limited to small series or to data collected by self-administered questionnaires among members of patient associations, with non-adherence varying between 5% and 70%, depending on the methods used and the patient age.72,73

Successful management of CD both from the medical and the psychological aspects requires proper education of patients and their families. Adherence to a GFD seems to be correlated with the knowledge and understanding of the disease both in adults and in children.74–76

Adherence to a GFD requires education, attention and time. Commercially available processed foods, although made out of safe cereals, may be contaminated by unknown amounts of wheat, rye, or barley. This is often a cause of stress in patients,77 and a reason for failing dietary adherence.10 The labeling of food is still a matter of debate in many countries and at the moment there is not a general rule for labeling food containing traces of gluten. Most European countries have accepted the definition of “gluten-free” as <20 parts per million (ppm; 6 mg equivalent), while those food products that contain 20–100 ppm gluten (up to 30 mg equivalent) are classified as “very low gluten.”78

Improving dietary adherence and defining GFD are among the key tasks of health care personnel meeting with patients with CD. One recent Finnish paper also suggested that treatment of children with a GFD might reduce the use of health care services.79

Risk of CD in family members

Informing the patient about the genetic background of CD, may prompt many patients to ask about the risk of CD in their parents, siblings, and children. The general consensus is that about 10% of first-degree relatives of patients with CD have CD.80 Most countries therefore recommend screening of first-degree relatives. Patients themselves should not be asked to shoulder the responsibility of having their relatives undergo screening, but they may still inform their relatives about their excess risk of CD—this may be especially important in relatives with gastrointestinal symptoms, signs of malabsorption and/or other immune-mediated disease.

Social activities and eating together

CD is not only about having a life-long disease, it is also about not always being able to join dinners, and eat the food that is served. This is of special concern in teenagers81 for whom belonging to a group and not standing out may be of major importance. This can potentially lead to lower dietary adherence. There is clear evidence that patients with CD are less likely to dine out in restaurants or at friends’ houses as a result of concerns regarding cross-contamination or inadvertent exposure to gluten.82

Patients may worry about the consequences of social situations leading to difficulties in dietary adherence. Unlike, for example. lactose intolerance, where patients can add lactase to help digest lactose if they choose to consume lactose, there are no such opportunities in CD.

Not all symptoms disappear

The GFD does not produce instantaneously normal duodenal mucosa, and in fact persistent mucosal abnormality is common.83,84 It is perhaps not surprising therefore that while patients generally feel better on a GFD, with an improved health-related quality of life having been demonstrated,85 not all symptoms will vanish in all patients. For most patients diarrhea will respond within six months, and on average within four weeks,86 but a small proportion will have persistent diarrhea after this even on a GFD,87 and in these patients it is often possible to find a second cause of diarrhea that needs treating. Some other symptoms respond less well to diet, and constipation and gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms may even be more common on the diet.88 The reasons for persisting symptoms can in essence be reduced to three groups (in patients who are truly adherent to diet89). Some symptoms will be those of another condition (the symptoms of this may have prompted the investigation leading to a diagnosis of CD, or it may have arisen since diagnosis, and the disease could be organic or functional), some symptoms as in the case of constipation may in effect be revealed by the removal of the features of CD (in this example removing the laxative effect of CD reveals the underlying constipation), and finally some may be due to CD truly refractory to GFD. Examples of second diagnoses that can be important in this setting include among many others Crohn’s disease, irritable bowel syndrome and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.90 Perhaps most important among the causes of ongoing symptoms due to second diagnoses is the small number of malignancies that present this way. There is good evidence that malignancies are more common in the period after diagnosis of CD, but not in long-term follow-up.91–93 Hence a lack of response to a GFD within 12 months should entail a more detailed investigation,11 and it is important for health care personnel to stress to patients that while it can take several months or even years before symptoms of CD improve, they should not deteriorate after the initiation of a GFD. In the event of such deterioration the patient must seek health care advice.

Internet

The Internet means that anyone with digital access can obtain an unlimited amount of information about CD. Among the top 10 hits from a Google search for Web sites about CD were two from Wikipedia, one from the Mayo Clinic, one from the United States (US) National Institutes of Health (NIH), one from Kidshealth.org, and five from patient organizations and support groups.

Many but not all of the top Internet sources on CD present peer-reviewed content. Access to Internet-based data on CD empowers the patient. This is almost exclusively for the good, but at the same time Internet content may not be updated, and it sometimes reinforces myths, and can therefore make the work of health care personnel harder. A recent evaluation of 100 top English-language Web sites showed that only 4% achieved the overall quality score that a priori was set as the minimum score for a Web site to be judged trustworthy and reliable. The authors concluded that the information on many Web sites addressing celiac disease was not sufficiently trustworthy and reliable for patients and also health care providers, thus they had the potential to mislead in decision making in CD.94 Another way to promote correct information is for physicians and other health care personnel to be present on the Internet themselves (e.g. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/celiac-disease/DS00319 or http://sklad.cumc.columbia.edu/celiacdiseasecenter/celiac-disease/). Directing the patient to more reputable sites may also ensure that the patient has the greatest chance of accessing accurate information. The Internet may also be used as an educational tool and resource, and an online intervention has been shown to improve dietary adherence.16

Currently, the biggest social media site is Facebook (www.facebook.com). Recent reports suggest that Facebook has more than 1 billon members (Wall Street Journal, October 4, 2012), which is more than the number of inhabitants in the US, Brazil, Russia, United Kingdom (UK) and Italy combined. Facebook contains a large number of celiac support groups, but also the gluten industry is amply represented on Facebook. Social media sites often have chat forums, and saved conversations between forum members make up valuable information resources.

YouTube (www.youtube.com) is a video-sharing Web site. It currently hosts more than 543,000 English-language films about either “celiac” or “coeliac” or “gluten” (June 5, 2014). A large proportion of these videos show how to bake without gluten, but some tell patient stories, or are presentations by health professionals.

Family involvement

Family involvement is almost inevitable in CD. It is common in chronic disease generally and CD specifically for family members to take on some responsibility for dietary adherence (even in adults).95 The role of the family in diet is of course even greater when the patient is a child, but there is little evidence to suggest that sharing the responsibility for diet with parents improves adherence.96 In general also though a GFD may not be fully adopted by unaffected family members, it will influence at least cooked meals they eat within the home.97 For this reason the family as a whole is likely to benefit from education on a GFD, and there is some evidence to suggest at least in children that those whose parents worry more about the long-term consequences of CD (but less about health in general), will comply with diet better.96

The involvement of the family in CD of course is not just their support in aiding dietary adherence, but also the effect that the diagnosis has on them. An accompanying family member will have all the same social restrictions of a GFD placed on them (for example, choice of restaurants when they are with the patient), or will be likely to face dilemmas around their relationship with the patient, or to impair dietary adherence.98 Further it can be demonstrated that these effects amount to an important reduction in the quality of life,99 and clearly the recognition of this by health care professionals is desirable.

Economics of CD

It is remarkable how few peer-reviewed publications there are on the cost of having CD confers on the individual. A PubMed search of the terms (“Celiac Disease” (MeSH)) AND “Cost of Illness” (MeSH) returns only 18 references (June 1, 2014). Recent primary care data from the UK indicate that CD is associated with increased costs both before and after diagnosis.100 Other data suggest that society and health care may actually save money after diagnosis (undiagnosed CD is often associated with frequent medical visits101), while the patient experiences increased costs after diagnosis.8,101 This increase is due at least largely to the cost of a GFD. US and UK studies have demonstrated that gluten-free products cost far more than their gluten-containing equivalents, and are less widely available than them.8,102 It has also been demonstrated that this cost and the difficulty in meeting it can affect the adherence with a GFD60 and that the difficulty in complying with diet has an important effect on quality of life.26 In recognition of the importance of these costs, some help in meeting them is provided in a variety of nations. Examples include tax relief on gluten-free products in Canada,103 the prescription of gluten-free products in the UK, and the provision of a lump sum of up to $5000 USD at diagnosis to children covered by certain private insurance companies in Sweden. For this reason it is important for patients to familiarize themselves with the financial help available to them within their own health care/tax system.

Another important aspect of the economics of CD from the patient perspective is its effect on employment. Again there are few data available regarding this, but in this regard at least what data are available are reassuring for patients since adult patients with CD do not appear to have reduced participation in the labor force.13

Complications and comorbidity

Patients with CD are at increased risk of a number of comorbid conditions, especially before but also after CD diagnosis.

CD causes gastrointestinal-related symptoms including malabsorption and anemia. Non-gastrointestinal manifestations are recognized and these include autoimmune diseases,104,105 dermatitis herpitiformis,106 neurological disorders,107 and amenorrhea.108 In CD, like type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis, particular HLA alleles are overrepresented among the patients.109 Patients can go into complete remission when they are put on a GFD, and they relapse when gluten is reintroduced into the diet. CD is in this respect unique among the chronic inflammatory HLA-associated diseases in that a critical environmental factor has been identified.41

With increasing use of antibody screening for CD, the number of patients with another disorder, such as type 1 diabetes and autoimmune thyroid disorder already at time of CD diagnosis, is increasing. Patients with more than one chronic disorder demand special consideration. They often express a need for information about complications, and health care personnel play an important role in quantifying risks, and explaining the difference between (often high) relative risks versus more moderate absolute risks for complications.

One complication is osteoporosis and fractures. Patients with CD suffer from malabsorption of calcium and despite treatment with a GFD, bone mineral density may not normalize.110 This can be one explanation why fractures are more common in CD both before and after diagnosis.111 Although the relative fracture risk decreases after CD diagnosis it does not seem to fully normalize over time, especially not in individuals with persistent VA.38

Malignancy is another complication. Recent research has, however, shown that overall malignancy risk in CD is similar to that of non-celiac individuals, with the exception of an increased risk of lymphoproliferative cancer92,112 and potentially also gastrointestinal cancer.6,91 The risk is obvious, so patients and their family focus on the high relative risk of lymphoproliferative cancer, while the absolute risk of this cancer is more relevant to the individual patient.

One way to explain relative risks is to describe the risk of lymphoproliferative cancer, which is perhaps the most feared complication in CD. In a given year, three out of any 10,000 individuals will develop lymphoma.92 In that same year, seven out of 10,000 patients with CD will develop lymphoma. Seven divided by three is between two and three, which means patients with CD are at a two- to three-fold increased risk of developing lymphoma. Turning the absolute risks (three of 10,000 and seven of 10,000) around is another way of giving the patient a perspective on his or her lymphoma risk (and other risks as well). A total of 99.97% (that is one minus three of 10,000) of healthy individuals will not have lymphoma in the coming year, while 99.93% of CD patients will not have lymphoma in the coming year.

Subfertility in CD has been much debated. Three large papers have shown a normal overall fertility in women with CD113–115 (and one paper in men with CD116). In the largest of these studies, Zugna et al. found a decrease in fertility just before diagnosis114 (a decrease that may be due to increased inflammation just prior to diagnosis, but also due to postponement of pregnancy because of medical investigation), but importantly women with diagnosed CD had the same fertility as women from the general population.

The advent of serological markers has meant that more high-risk individuals now undergo screening for CD. This includes patients with certain autoimmune diseases such as patients with type 1 diabetes and autoimmune thyroid disease. Hence, a large share of CD patients already have other diagnoses when the CD is discovered. Dietary treatment in patients with concomitant type 1 diabetes and CD can become complicated, and support from a dietitian is important. Some data117–120 suggest that CD influences the prevalence of complications in patients with type 1 diabetes. Whether a GFD will have a positive influence on the long-term HbA1C in patients with both type 1 diabetes and CD is still under debate.121

Promoting health in CD

Some patients may have heard or read that smoking is negatively associated with CD. The relationship with smoking is intricate and there are studies suggesting that smoking actually decreases the risk of CD,122 as well as studies suggesting a neutral or positive association.123 However, no matter what the effect of smoking on the risk of developing CD, it is likely to increase the risk of a number of diseases, and will not alleviate CD once it has developed. For patients with CD as for the rest of the population, cardiovascular disease and cancer (both linked to smoking) are the most common causes of death in CD.7 Patients with CD should therefore be encouraged not to smoke.

CD is associated with low body mass index.124 Institution of a GFD is often followed by a weight increase. Patients often report or perceive that the sugar content of gluten-free products (and thus calories) may be higher than in gluten-containing products. The only study to try and address this did not support this commonly held perception.125,126

Though a risk of increasing lipid levels and thereby cardiovascular disease has been postulated, Lewis et al. 2009127 did not see an increase in adverse lipid levels with GFD. It seems unlikely therefore that GFD will increase cardiovascular risk by this route. It is nonetheless sensible that excessive weight gain after diagnosis of CD should be discouraged.

Relevant societies

Patients should be encouraged to seek out community support. Patients’ associations all over the world provide practical information and sensitize society and support the diffusion of knowledge about GFD requirements. Membership of CD support groups has been linked to higher dietary adherence.60 See also: http://celiacdisease.about.com/od/theceliactraveler/a/IntlSocieties.htm.

Future treatment of CD

Future treatment is one of the topics patients most often want to discuss with their physicians,10 and a large number of substances are currently undergoing early testing (the NIH currently lists almost 100 clinical trials (enrolling, recruiting, or completed) on CD, although not all of them concern GFD alternatives; http://clinicaltrials.gov). Future medications may either improve the prognosis of CD, or allow patients to consume a gluten-containing diet.

The currently available potential therapies focus on three main strategies: reduced gluten availability via either gluten enzyme degradation by oral protaeses128–131 or oral polymeric resins that interfere with the binding of gluten,132 inhibition of small intestinal permeability by the zonulin antagonist AT-1001 (which is undergoing Phase II clinical trials133,134) and modulation of the immune response. The third strategy includes a different class of drugs interfering with the inflammation cascade. Among them are the TG2 inhibitors,135 blockers of HLA-DQ-mediated T-cell activation,136 vaccines,137,138 and inhibitors of cytokines and interferon gamma (IFN-γ)139,140 that are being investigated for other autoimmune diseases. There are also several ongoing trials with Larazotide acetate.133,134

Finally, infestation with the hookworm Necator americanus has also been suggested as a possible treatment for CD. The rationale behind this therapy is that the increased prevalence of autoimmune disorders in developed countries is closely paralleled by a disappearance of intestinal parasites. These parasites are thought to play an important role in modulating the host’s immune system. A Phase II clinical trial has been undertaken with this hookworm in CD.141

Alternatives to dietary treatment142,143 can actually serve as an opportunity for a discussion about the characteristics of CD with the patient (properties of gluten, uptake of gluten from the mucosa, how inflammation is involved in CD, etc.).

At the same time we the authors want to stress that most, if not all, alternatives to the GFD are in early phases of testing and physicians should at this stage not give patients the false impression that treatments other than the GFD are just around the corner. At least in the near future, and probably longer, a GFD will be the dominant, if not the only, available treatment in CD. Furthermore, it should be emphasized that a GFD has a long-established safety profile and is non-toxic while newer agents are as yet unproven.

Discussion

In this paper we have discussed patient support in CD. This should be an integral part of CD management. Despite its likely importance for management success, there are few data we could find on issues such as the economic burden of CD, patient-centered care in CD, and continuity of patient care in CD. It is important to recognize that patients themselves wish for high-quality information and access to both a dietitian and physician with an interest in CD.144

Physicians should take patient support and information seriously because research suggests that better content and quality of patient information improves dietary adherence that currently is the only available treatment in CD. Two Swedish randomized clinical trials have shown that patient education may have an impact on both gastrointestinal symptoms and on general well-being in CD.17,18

It was also beyond the scope of this paper to give recommendations on supplements.

As for any wide-ranging narrative review, there are limitations to our paper. Among those we would like the reader to recognize are that it was beyond the scope of this paper to review economic benefits and patient support groups in more than a limited number of countries. We have also not reviewed topics such as GFD and complications in CD in detail. Readers seeking further information on these topics may like to start by reading the recent review on CD management to which the current authors contributed.11

In our section on the etiology of CD we tried to outline some key facts about CD, but in a way that may help health care personnel inform patients with CD.

This study has some limitations: We did not formalize patient involvement in the writing of our paper, but tried to reach out to the CD community through social media (www.facebook.com), through which six different organizations were contacted. Individual authors decided on what paper to include or exclude in the literature study. Generally it is preferable if every paper is read by at least two experts who then decide on what papers (and for what reason) should be included in the review. Hence, we cannot say that this review was systematic. Neither can we rule out that there are relevant data on patient support in other databases than PubMed (we restricted our literature search to this database). Finally, there are few randomized clinical trials in our field of research, and hence the grade of evidence is low.

In conclusion, we suggest that patient support and information should be an integral part of the management of CD.

Appendix—Search terms

We performed the following two searches for this paper. PubMed was searched through June 1, 2014

((“Costs and Cost Analysis” (MeSH) OR “Economics” (MeSH) OR “economics” (Subheading) OR “Cost-Benefit Analysis” (MeSH) OR “Cost Control” (MeSH) OR “Cost Sharing” (MeSH) OR “Cost Savings” (MeSH) OR “Health Care Costs” (MeSH) OR “Direct Service Costs” (MeSH) OR “Hospital Costs” (MeSH) OR “Employer Health Costs” (MeSH) OR “Drug Costs” (MeSH)) AND “Celiac Disease” (MeSH)) = 115 hits.

(“education” (Subheading) OR “education” (all fields) OR “educational status” (MeSH Terms) OR (“educational” (all fields) AND “status” (all fields)) OR “educational status” (all fields) OR “education” (all fields) OR “education” (MeSH Terms)) AND (“coeliac disease” (all fields) OR “celiac disease” (MeSH terms) OR (“celiac” (all fields) AND “disease” (all fields)) OR “celiac disease” (all fields)) = 291 hits.

Funding

JFL was supported by grants from The Swedish Society of Medicine, the Swedish Research Council-Medicine (522-2A09-195), the Fulbright commission.

Conflict of interest

DSS has received an educational grant from Dr Schär (a gluten-free food manufacturer) to undertake an investigator-led research study on gluten sensitivity. The other authors have nothing to declare.

References

- 1.Dubé C, Rostom A, Sy R, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in average-risk and at-risk Western European populations: A systematic review. Gastroenterology 2005; 128: S57–S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gutierrez-Achury J, Coutinho de Almeida R, Wijmenga C. Shared genetics in coeliac disease and other immune-mediated diseases. J Intern Med 2011; 269: 591–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker MM, Murray JA. An update in the diagnosis of coeliac disease. Histopathology 2010; 59: 166–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hadithi M, von Blomberg BM, Crusius JB, et al. Accuracy of serologic tests and HLA-DQ typing for diagnosing celiac disease. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147: 294–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hopper AD, Hadjivassiliou M, Hurlstone DP, et al. What is the role of serologic testing in celiac disease? A prospective, biopsy-confirmed study with economic analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6: 314–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.West J, Logan RF, Smith CJ, et al. Malignancy and mortality in people with coeliac disease: Population based cohort study. BMJ 2004; 329: 716–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ludvigsson JF, Montgomery SM, Ekbom A, et al. Small-intestinal histopathology and mortality risk in celiac disease. JAMA 2009; 302: 1171–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee AR, Ng DL, Zivin J, et al. Economic burden of a gluten-free diet. J Hum Nutr Diet 2007; 20: 423–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitaker JK, West J, Holmes GK, et al. Patient perceptions of the burden of coeliac disease and its treatment in the UK. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 29: 1131–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ukkola A, Maki M, Kurppa K, et al. Patients’ experiences and perceptions of living with coeliac disease—implications for optimizing care. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2012; 21: 17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ludvigsson JF, Bai JC, Biagi F, et al. Diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease: Guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut 2014; 63: 1210–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinos S, Kurppa K, Ukkola A, et al. Burden of illness in screen-detected children with celiac disease and their families. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012; 55: 412–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calsbeek H, Rijken M, Dekker J, et al. Disease characteristics as determinants of the labour market position of adolescents and young adults with chronic digestive disorders. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 18: 203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pettersson HB, Fälth-Magnusson K, Persliden J, et al. Radiation risk and cost-benefit analysis of a paediatric radiology procedure: Results from a national study. Br J Radiol 2005; 78: 34–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine –Levels of Evidence. Oxford: Centre for Evidence-based Medicine, Oxford University, 2009.

- 16.Sainsbury K, Mullan B, Sharpe L. A randomized controlled trial of an online intervention to improve gluten-free diet adherence in celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 811–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobsson LR, Friedrichsen M, Göransson A, et al. Impact of an active patient education program on gastrointestinal symptoms in women with celiac disease following a gluten-free diet: A randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology Nurs 2012; 35: 200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ring Jacobsson L, Friedrichsen M, Göransson A, et al. Does a Coeliac School increase psychological well-being in women suffering from coeliac disease, living on a gluten-free diet? J Clin Nurs 2012; 21: 766–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer KG, Fasshauer M, Nebel IT, et al. Comparative analysis of conventional training and a computer-based interactive training program for celiac disease patients. Patient Educ Couns 2004; 54: 353–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dennis M, Leffler D. Real life with celiac disease, Bethesda: American Gastroenterology Association, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green PH, Jones R. Celiac disease: A hidden epidemic, New York: HarperCollins, 2010, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomlin J, Slater H, Muganthan T, et al. Parental knowledge of coeliac disease. Inform Health Soc Care. Epub ahead of print 30 April 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Drossman DA, Brandt LJ, Sears C, et al. A preliminary study of patients’ concerns related to GI endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91: 287–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quine MA, Bell GD, McCloy RF, et al. Prospective audit of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in two regions of England: Safety, staffing, and sedation methods. Gut 1995; 36: 462–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ciacci C, Iavarone A, Mazzacca G, et al. Depressive symptoms in adult coeliac disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 1998; 33: 247–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barratt SM, Leeds JS, Sanders DS. Quality of life in coeliac disease is determined by perceived degree of difficulty adhering to a gluten-free diet, not the level of dietary adherence ultimately achieved. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2011; 20: 241–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Byström IM, Hollén E, Fälth-Magnusson K, et al. Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with celiac disease: From the perspectives of children and parents. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2012; 2012: 986475–986475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rewers M. Epidemiology of celiac disease: What are the prevalence, incidence, and progression of celiac disease? Gastroenterology 2005; 128: S47–S51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murray JA, Van Dyke C, Plevak MF, et al. Trends in the identification and clinical features of celiac disease in a North American community, 1950–2001. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003; 1: 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vilppula A, Kaukinen K, Luostarinen L, et al. Increasing prevalence and high incidence of celiac disease in elderly people: A population-based study. BMC Gastroenterol 2009; 9: 49–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Talley NJ, Valdovinos M, Petterson TM, et al. Epidemiology of celiac sprue: A community-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 1994; 89: 843–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Catassi C, Fasano A. New developments in childhood celiac disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2002; 4: 238–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ludvigsson JF, Ansved P, Fälth-Magnusson K, et al. Symptoms and signs have changed in Swedish children with coeliac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2004; 38: 181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rampertab SD, Pooran N, Brar P, et al. Trends in the presentation of celiac disease. Am J Med 2006; 119: 355.e9–355.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haines ML, Anderson RP, Gibson PR. Systematic review: The evidence base for long-term management of coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008; 28: 1042–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tuire I, Marja-Leena L, Teea S, et al. Persistent duodenal intraepithelial lymphocytosis despite a long-term strict gluten-free diet in celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 1563–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rubio-Tapia A, Rahim MW, See JA, et al. Mucosal recovery and mortality in adults with celiac disease after treatment with a gluten-free diet. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 1412–1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lebwohl B, Michaelsson K, Green PH, et al. Persistent mucosal damage and risk of fracture in celiac disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014; 99: 609–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lebwohl B, Granath F, Ekbom A, et al. Mucosal healing and risk for lymphoproliferative malignancy in celiac disease: A population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2013; 159: 169–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lebwohl B, Granath F, Ekbom A, et al. Mucosal healing and mortality in coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013; 37: 332–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sollid LM. Molecular basis of celiac disease. Annu Rev Immunol 2000; 18: 53–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ludvigsson JF, Green PH. Clinical management of coeliac disease. J Intern Med 2011; 269: 560–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Green PH, Jabri B. Coeliac disease. Lancet 2003; 362: 383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolters VM, Wijmenga C. Genetic background of celiac disease and its clinical implications. Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103: 190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Craig D, Robins G, Howdle PD. Advances in celiac disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2007; 23: 142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rostom A, Murray JA, Kagnoff MF. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2006; 131: 1981–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ludvigsson JF, Ludvigsson J, Ekbom A, et al. Celiac disease and risk of subsequent type 1 diabetes: A general population cohort study of children and adolescents. Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 2483–2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cosnes J, Cellier C, Viola S, et al. Incidence of autoimmune diseases in celiac disease: Protective effect of the gluten-free diet. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6: 753–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhernakova A, van Diemen CC, Wijmenga C. Detecting shared pathogenesis from the shared genetics of immune-related diseases. Nat Rev Genet 2009; 10: 43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lionetti E, Castellaneta S, Francavilla R, et al. Introduction of gluten, HLA status, and the risk of celiac disease in children. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 1295–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vriezinga SL, Auricchio R, Bravi E, et al. Randomized feeding intervention in infants at high risk for celiac disease. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 1304–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Akobeng AK, Ramanan AV, Buchan I, et al. Effect of breast feeding on risk of coeliac disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Arch Dis Child 2006; 91: 39–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ludvigsson JF, Fasano A. Timing of introduction of gluten and celiac disease risk. Ann Nutr Metab 2012; 60(Suppl 2): 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sandberg-Bennich S, Dahlquist G, Kallen B. Coeliac disease is associated with intrauterine growth and neonatal infections. Acta Paediatr 2002; 91: 30–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roberts SE, Williams JG, Meddings D, et al. Perinatal risk factors and coeliac disease in children and young adults: A record linkage study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 29: 222–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ludvigsson JF, Ludvigsson J. Parental smoking and risk of coeliac disease in offspring. Scand J Gastroenterol 2005; 40: 336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kagnoff MF, Paterson YJ, Kumar PJ, et al. Evidence for the role of a human intestinal adenovirus in the pathogenesis of coeliac disease. Gut 1987; 28: 995–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Welander A, Tjernberg AR, Montgomery SM, et al. Infectious disease and risk of later celiac disease in childhood. Pediatrics 2010; 125: e530–e536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ciacci C, Siniscalchi M, Bucci C, et al. Life events and the onset of celiac disease from a patient’s perspective. Nutrients 2013; 5: 3388–3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leffler DA, Edwards-George J, Dennis M, et al. Factors that influence adherence to a gluten-free diet in adults with celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci 2008; 53: 1573–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bardella MT, Molteni N, Prampolini L, et al. Need for follow up in coeliac disease. Arch Dis Child 1994; 70: 211–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ludvigsson JF, Montgomery SM, Ekbom A. Celiac disease and risk of adverse fetal outcome: A population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology 2005; 129: 454–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khashan AS, Henriksen TB, Mortensen PB, et al. The impact of maternal celiac disease on birthweight and preterm birth: A Danish population-based cohort study. Hum Reprod 2010; 25: 528–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Olén O, Askling J, Ludvigsson JF, et al. Coeliac disease characteristics, compliance to a gluten free diet and risk of lymphoma by subtype. Dig Liver Dis 2011; 43: 862–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ciacci C, Iovino P, Amoruso D, et al. Grown-up coeliac children: The effects of only a few years on a gluten-free diet in childhood. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005; 21: 421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ford S, Howard R, Oyebode J. Psychosocial aspects of coeliac disease: A cross-sectional survey of a UK population. Br J Health Psychol 2012; 17: 743–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee AR, Ng DL, Diamond B, et al. Living with coeliac disease: Survey results from the USA. J Hum Nutr Diet 2012; 25: 233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nachman F, del Campo MP, González A, et al. Long-term deterioration of quality of life in adult patients with celiac disease is associated with treatment noncompliance. Dig Liver Dis 2010; 42: 685–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mustalahti K, Lohiniemi S, Collin P, et al. Gluten-free diet and quality of life in patients with screen-detected celiac disease. Eff Clin Pract 2002; 5: 105–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vilppula A, Kaukinen K, Luostarinen L, et al. Clinical benefit of gluten-free diet in screen-detected older celiac disease patients. BMC Gastroenterol 2011; 11: 136–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Paavola A, Kurppa K, Ukkola A, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms and quality of life in screen-detected celiac disease. Dig Liver Dis 2012; 44: 814–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hall NJ, Rubin G, Charnock A. Systematic review: Adherence to a gluten-free diet in adult patients with coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 30: 315–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zarkadas M, Cranney A, Case S, et al. The impact of a gluten-free diet on adults with coeliac disease: Results of a national survey. J Hum Nutr Diet 2006; 19: 41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ciacci C, Cirillo M, Cavallaro R, et al. Long-term follow-up of celiac adults on gluten-free diet: Prevalence and correlates of intestinal damage. Digestion 2002; 66: 178–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jackson PT, Glasgow JF, Thom R. Parents’ understanding of coeliac disease and diet. Arch Dis Child 1985; 60: 672–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hauser W, Stallmach A, Caspary WF, et al. Predictors of reduced health-related quality of life in adults with coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 25: 569–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Veen M, te Molder HF, Gremmen B, et al. Quitting is not an option: An analysis of online diet talk between celiac disease patients. Health (London) 2010; 14: 23–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.European Commission. COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 41/2009 of 20 January 2009 concerning the composition and labelling of foodstuffs suitable for people intolerant to gluten, 2009.

- 79.Mattila E, Kurppa K, Ukkola A, et al. Burden of illness and use of health care services before and after celiac disease diagnosis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013; 57: 53–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rubio-Tapia A, Van Dyke CT, Lahr BD, et al. Predictors of family risk for celiac disease: A population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6: 983–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ljungman G, Myrdal U. Compliance in teenagers with coeliac disease—a Swedish follow-up study. Acta Paediatr 1993; 82: 235–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Karajeh MA, Hurlstone DP, Patel TM, et al. Chefs’ knowledge of coeliac disease (compared to the public): A questionnaire survey from the United Kingdom. Clin Nutr 2005; 24: 206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hutchinson JM, West NP, Robins GG, et al. Long-term histological follow-up of people with coeliac disease in a UK teaching hospital. QJM 2010; 103: 511–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wahab PJ, Meijer JW, Mulder CJ. Histologic follow-up of people with celiac disease on a gluten-free diet: Slow and incomplete recovery. Am J Clin Pathol 2002; 118: 459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gray AM, Papanicolas IN. Impact of symptoms on quality of life before and after diagnosis of coeliac disease: Results from a UK population survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2010; 10: 105–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Murray JA, Watson T, Clearman B, et al. Effect of a gluten-free diet on gastrointestinal symptoms in celiac disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 79: 669–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fine KD, Meyer RL, Lee EL. The prevalence and causes of chronic diarrhea in patients with celiac sprue treated with a gluten-free diet. Gastroenterology 1997; 112: 1830–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Carroccio A, Ambrosiano G, Di Prima L, et al. Clinical symptoms in celiac patients on a gluten-free diet. Scand J Gastroenterol 2008; 43: 1315–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Leffler DA, Dennis M, Hyett B, et al. Etiologies and predictors of diagnosis in nonresponsive celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 5: 445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rubio-Tapia A, Barton SH, Murray JA. Celiac disease and persistent symptoms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9: 13–17 quiz e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Elfstrom P, Granath F, Ye W, et al. Low risk of gastrointestinal cancer among patients with celiac disease, inflammation, or latent celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 10: 30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Elfström P, Granath F, Ekström Smedby K, et al. Risk of lymphoproliferative malignancy in relation to small intestinal histopathology among patients with celiac disease. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011; 103: 436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Askling J, Linet M, Gridley G, et al. Cancer incidence in a population-based cohort of individuals hospitalized with celiac disease or dermatitis herpetiformis. Gastroenterology 2002; 123: 1428–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McNally SL, Donohue MC, Newton KP, et al. Can consumers trust web-based information about celiac disease? Accuracy, comprehensiveness, transparency, and readability of information on the internet. Interact J Med Res 2012; 1: e1–e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gregory S. Living with chronic illness in the family setting. Sociol Health Illn 2005; 27: 372–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Anson O, Weizman Z, Zeevi N. Celiac disease: Parental knowledge and attitudes of dietary compliance. Pediatrics 1990; 85: 98–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.van Overbeek FM, Uil-Dieterman IG, Mol IW, et al. The daily gluten intake in relatives of patients with coeliac disease compared with that of the general Dutch population. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1997; 9: 1097–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sverker A, Ostlund G, Hallert C, et al. Sharing life with a gluten-intolerant person—the perspective of close relatives. J Hum Nutr Diet 2007; 20: 412–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.de Lorenzo CM, Xikota JC, Wayhs MC, et al. Evaluation of the quality of life of children with celiac disease and their parents: A case-control study. Qual Life Res 2012; 21: 77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Violato M, Gray A, Papanicolas I, et al. Resource use and costs associated with coeliac disease before and after diagnosis in 3,646 cases: Results of a UK primary care database analysis. PLoS One 2012; 7: e41308–e41308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Long KH, Rubio-Tapia A, Wagie AE, et al. The economics of coeliac disease: A population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010; 32: 261–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Singh J, Whelan K. Limited availability and higher cost of gluten-free foods. J Hum Nutr Diet 2011; 24: 479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gluten-free products: Incremental cost of Gluten-free (GF) products, an eligible medical expense. Canada Revenue Agency, 2012.

- 104.Cronin CC, Shanahan F. Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and coeliac disease. Lancet 1997; 349: 1096–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Counsell CE, Taha A, Ruddell WS. Coeliac disease and autoimmune thyroid disease. Gut 1994; 35: 844–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bizzaro N, Villalta D, Tonutti E, et al. Association of celiac disease with connective tissue diseases and autoimmune diseases of the digestive tract. Autoimmun Rev 2003; 2: 358–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hadjivassiliou M, Gibson A, Davies-Jones GA, et al. Does cryptic gluten sensitivity play a part in neurological illness? Lancet 1996; 347: 369–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Santonicola A, Iovino P, Cappello C, et al. From menarche to menopause: The fertile life span of celiac women. Menopause 2011; 18: 1125–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Thorsby E. Invited anniversary review: HLA associated diseases. Hum Immunol 1997; 53: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bode S, Hassager C, Gudmand-Hoyer E, et al. Body composition and calcium metabolism in adult treated coeliac disease. Gut 1991; 32: 1342–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ludvigsson JF, Michaelsson K, Ekbom A, et al. Coeliac disease and the risk of fractures—a general population-based cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 25: 273–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Grainge MJ, West J, Solaymani-Dodaran M, et al. The long-term risk of malignancy following a diagnosis of coeliac disease or dermatitis herpetiformis: A cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012; 35: 730–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tata LJ, Card TR, Logan RF, et al. Fertility and pregnancy-related events in women with celiac disease: A population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology 2005; 128: 849–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zugna D, Richiardi L, Akre O, et al. A nationwide population-based study to determine whether coeliac disease is associated with infertility. Gut 2010; 59: 1471–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hogen Esch CE, Van Rijssen MJ, Roos A, et al. Screening for unrecognized coeliac disease in subfertile couples. Scand J Gastroenterol 2011; 46: 1423–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zugna D, Richiardi L, Akre O, et al. Celiac disease is not a risk factor for infertility in men. Fertil Steril 2011; 95: 1709–1713.e1–e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Leeds JS, Hopper AD, Hadjivassiliou M, et al. High prevalence of microvascular complications in adults with type 1 diabetes and newly diagnosed celiac disease. Diabetes Care 2011; 34: 2158–2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mollazadegan K, Fored M, Lundberg S, et al. Risk of renal disease in patients with both type 1 diabetes and coeliac disease. Diabetologia 2014; 57: 1339–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mollazadegan K, Sanders DS, Ludvigsson J, et al. Long-term coeliac disease influences risk of death in patients with type 1 diabetes. J Intern Med 2013; 274: 273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mollazadegan K, Kugelberg M, Montgomery SM, et al. A population-based study of the risk of diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 1 diabetes and celiac disease. Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 316–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hansen D, Brock-Jacobsen B, Lund E, et al. Clinical benefit of a gluten-free diet in type 1 diabetic children with screening-detected celiac disease: A population-based screening study with 2 years’ follow-up. Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 2452–2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Snook JA, Dwyer L, Lee-Elliott C, et al. Adult coeliac disease and cigarette smoking. Gut 1996; 39: 60–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ludvigsson JF, Montgomery SM, Ekbom A. Smoking and celiac disease: a population-based cohort study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 3: 869–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Olén O, Montgomery SM, Marcus C, et al. Coeliac disease and body mass index: A study of two Swedish general population-based registers. Scand J Gastroenterol 2009; 44: 1198–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ohlund K, Olsson C, Hernell O, et al. Dietary shortcomings in children on a gluten-free diet. J Hum Nutr Diet 2010; 23: 294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wild D, Robins GG, Burley VJ, et al. Evidence of high sugar intake, and low fibre and mineral intake, in the gluten-free diet. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010; 32: 573–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lewis NR, Sanders DS, Logan RF, et al. Cholesterol profile in people with newly diagnosed coeliac disease: A comparison with the general population and changes following treatment. Br J Nutr 2009; 102: 509–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lahdeaho ML, Kaukinen K, Laurila K, et al. Glutenase ALV003 attenuates gluten-induced mucosal injury in patients with celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2014; 146: 1649–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tye-Din JA, Stewart JA, Dromey JA, et al. Comprehensive, quantitative mapping of T cell epitopes in gluten in celiac disease. Sci Transl Med 2010; 2: 41ra51–41ra51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Mitea C, Havenaar R, Drijfhout JW, et al. Efficient degradation of gluten by a prolyl endoprotease in a gastrointestinal model: Implications for coeliac disease. Gut 2008; 57: 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ehren J, Morón B, Martin E, et al. A food-grade enzyme preparation with modest gluten detoxification properties. PLoS One 2009; 4: e6313–e6313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Liang L, Pinier M, Leroux JC, et al. Interaction of alpha-gliadin with polyanions: Design considerations for sequestrants used in supportive treatment of celiac disease. Biopolymers 2010; 93: 418–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Leffler DA, Kelly CP, Abdallah HZ, et al. A randomized, double-blind study of larazotide acetate to prevent the activation of celiac disease during gluten challenge. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 1554–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kelly CP, Green PH, Murray JA, et al. Larazotide acetate in patients with coeliac disease undergoing a gluten challenge: A randomised placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013; 37: 252–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Grosso H, Mouradian MM. Transglutaminase 2: Biology, relevance to neurodegenerative diseases and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol Ther 2012; 133: 392–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kapoerchan VV, Wiesner M, Hillaert U, et al. Design, synthesis and evaluation of high-affinity binders for the celiac disease associated HLA-DQ2 molecule. Mol Immunol 2010; 47: 1091–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Anderson RP, Degano P, Godkin AJ, et al. In vivo antigen challenge in celiac disease identifies a single transglutaminase-modified peptide as the dominant A-gliadin T-cell epitope. Nat Med 2000; 6: 337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Huibregtse IL, Marietta EV, Rashtak S, et al. Induction of antigen-specific tolerance by oral administration of Lactococcus lactis delivered immunodominant DQ8-restricted gliadin peptide in sensitized nonobese diabetic Abo Dq8 transgenic mice. J Immunol 2009; 183: 2390–2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Yokoyama S, Watanabe N, Sato N, et al. Antibody-mediated blockade of IL-15 reverses the autoimmune intestinal damage in transgenic mice that overexpress IL-15 in enterocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106: 15849–15854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Reinisch W, de Villiers W, Bene L, et al. Fontolizumab in moderate to severe Crohn’s disease: A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple-dose study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010; 16: 233–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.McSorley HJ, Gaze S, Daveson J, et al. Suppression of inflammatory immune responses in celiac disease by experimental hookworm infection. PLoS One 2011; 6: e24092–e24092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Sollid LM, Khosla C. Novel therapies for coeliac disease. J Intern Med 2011; 269: 604–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Rashtak S, Murray JA. Review article: Coeliac disease, new approaches to therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012; 35: 768–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Bebb JR, Lawson A, Knight T, et al. Long-term follow-up of coeliac disease—what do coeliac patients want? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006; 23: 827–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]