Abstract

Background

There exists a wide variation in the reported incidence of coeliac disease in recent decades. We aimed to evaluate the incidence rate of coeliac diagnoses performed in an Italian region, Campania, between 2011 and 2013 and its variation therein.

Methods

All coeliac diagnoses made from 2011 to 2013 and registered within the Campania coeliac disease register (CeliacDB) were identified. Incidence rates were analysed by sex, age and province of residence, with a Poisson model fitted to determine incidence rate ratios.

Results

We found 2049 coeliac disease diagnoses registered in the CeliacDB between 2011 and 2013; 1441 of these patients were female (70.4%) and 1059 were aged less than 19 years (51.7%). The overall incidence of coeliac disease in Campania was 11.8 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 11.3–12.3) during the study period, with marked variation by age [27.4 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 25.8–29.1) in children under 19 years of age and 7.3 per 100,000 (95% CI 6.8–7.8) in adults] and sex [16.1 per 100,000 person-years in females (95% CI 15.3–16.9) and 7.2 per 100,000 person-years in males (95% CI 6.6–7.8)]. Coeliac disease incidence was roughly similar in Naples, Salerno, Caserta and Avellino, but about half in Benevento. More than 80% of our study population was diagnosed by the combination of positive antitransglutaminase IgA and Marsh 3. More than half of the patients were symptomatic at the time of coeliac disease diagnosis (39.7% had a classical presentation and 21.1% a non-classical one according to the Oslo definition).

Conclusions

Coeliac disease incidence was roughly similar among Campania provinces, except in Benevento where it was about half, probably due to less awareness of coeliac disease in this area. The incidence of coeliac disease in Campania appears to be lower than that reported by most of the previous literature, suggesting the necessity of new coeliac awareness programmes.

Keywords: Coeliac disease, incidence, clinical presentation, Italy

Introduction

Epidemiological studies have described a two- to six-fold increase in the incidence of coeliac disease (CD) in the populations of Western countries1 in the last two decades; however, there exists a wide variation of the reported CD incidence since the year 2000, possibly due to differences in the study populations and ascertainment of cases in these countries,2–11 but the data from Italy come only from small studies. In Italy, coeliac patients need to receive a disease certificate from secondary outpatient clinics to benefit from a monthly payment to spend on gluten-free food. Therefore, patients diagnosed with CD are evaluated by at least one CD secondary centre which confirms the diagnosis and releases the disease certificate.

Two Italian studies have reported the CD incidence in two small Italian provinces, retrieving the number of CD patients from two different sources. The first study was conducted in Brescia10 and reported the data on newly diagnosed coeliac patients collected by the Celiac Disease Study Group (composed of gastroenterologists, paediatricians and pathologists working in the eight hospitals of the area), between 2000 and 2003. The authors found an incidence of CD of 17 per 100,000 person-years. Another study, conducted in Terni,7 found an incidence of CD of 27.35 and 4.52 per 100,000 inhabitants in females and males, respectively, in 2010. However, because of the small sample size and small areas considered, these findings cannot be considered representative of the overall incidence of CD in Italy. In Campania the secondary CD centres have been asked to register every new patient (since 2006) with a CD diagnosis on an online platform to generate the certificate (CeliaDB).12 Therefore, through this platform it is possible to retrieve information on each patient at the time of CD diagnosis including date of diagnosis, region of diagnosis, demographics and mode of diagnosis.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the incidence rate of CD diagnoses performed in Campania between 2011 and 2013, employing the data registered online by all the secondary regional CD centres, looking at the differences in age, sex and province of residence.

Material and methods

Database (CeliaDB)

In Campania, only two university medical centres located in Naples (one for children, the other one for adults) have been exclusively committed since the 1980s to the diagnosis and follow-up of CD. However, the increasing number of diagnoses in recent decades has required an increase in the number of specialized centres spread throughout the region. The Campania Region Celiac Network was established in 2006, and the individuals responsible for the centres were trained to pursue the diagnosis of CD following shared protocols. Moreover, all secondary centres were progressively invited to register all previous CD diagnoses and each newly diagnosed person into the CeliaDB. This database was created as part of an educational project on CD sponsored by the Regione Campania.12,13 At the end of 2010, 31 secondary centres were invited to take part to the project (16 in Naples, seven in Salerno, four in Caserta, two in Avellino and two in Benevento). All residents newly identified as affected with CD in the Campania region need a certificate from one of these centres to receive a monthly payment to spend on gluten-free food. Every participating centre was provided with a username and password to access the database. Demographic data, signs and symptoms at diagnosis and modes of diagnosis of each new coeliac patient are inserted into the database, after informed consent, by each centre at the time of CD diagnosis to obtain the CD certificate. Data from this register have been recently used in national multicentre epidemiological studies on complications of CD.14--16

Study population

All new coeliac diagnoses made from 2011 to 2013 and registered within the CeliaDB17 in Campania were identified. Patients received a CD diagnosis and were included in the database if they had a duodenal biopsy showing intestinal damage, including lesions at scoring least 1 according to Marsh classification,18 associated with positive anti-tissue transglutaminase/endomysial antibodies, or in the case of no biopsy, positive anti-tissue transglutaminase/endomysial antibodies and genetic predisposition (HLA testing), accompanied by a clinical reason explaining why the biopsy was not performed. In the case of IgA deficiency, or in the case of seronegative CD, details on IgA total value, HLA testing and biopsy result had to be always reported in the database.

Data on sex, age, signs and symptoms at diagnosis, how the CD diagnosis was performed (serology, histology, HLA), and province of residence were collected for each patient. Patients living outside Campania’s provinces at the time of diagnosis but who received their CD certificate in one of the Campania centres were excluded.

The resident population in Campania was defined according to Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) data.19 ISTAT’s activities include the census of the population, economic censuses and a number of social, economic and environmental surveys and analyses. ISTAT is by far the largest producer of statistical information in Italy, and is an active member of the European Statistical System.

Statistical analyses

We calculated the incidence rate of CD by dividing the number of newly diagnosed CD cases by the time that people spent during the study period (person-years) and estimated 95% Confidence Intervals (CI). The date of CD diagnosis was the date of the duodenal biopsy which confirmed the diagnosis or, when it was missing, the date of certificate release. We assumed that each resident in Campania in 2011–2013 spent the whole year being “at risk,” so our denominator was estimated from the sum of the residents in 2011, 2012 and 2013, respectively, according to ISTAT data. We stratified disease incidence by sex, age group (categorized as 0–4, 5–19, 20–29, 30–49, 50–69 and 70 years and over, similarly to those present in the ISTAT data), calendar year and province of residence, (Naples, Salerno, Caserta, Avellino, Benevento). Incidence rates were presented per 100,000 person-years with a Poisson model fitted to determine incidence rate ratio (IRR). These IRRs were fully adjusted for sex, age group, calendar year (2011, 2012, 2013) and province of residence. We assessed the potential interaction between age and province of residence using the likelihood ratio test (LRT). The percentages of mode of CD diagnosis and the clinical presentation at the time of diagnosis were reported in each age group. Missing data were always considered as a separated category.

Results

In total, 26 CD centres actively used the CeliacDB from 2011 and 2013 to produce certification. Five centres were considered to be inactive as they registered fewer than 10 patients in the period of study (two in Naples, one in Salerno, one in Avellino and one in Benevento). In 2011 the total population of Campania was 5,834,056 persons, in 2012 5,764,424 persons and 5,769,750 in 2013, with a percentage of females of 51.5% in each year. Therefore, the study had a total follow-up time of 17,368,230 person-years. According to ISTAT data, in 2013 most people lived in Naples with a population of 3,055,339, followed by Salerno with 1,093,453 inhabitants, Caserta with 908,784 inhabitants and Avellino and Benevento with 428,523 and 283,651, respectively. The population distribution in the previous years was roughly similar.

Overall incidence

All patients with a CD diagnosis gave their written informed consent to be included in the Campania registry. The Campania register listed 10,511 patients at the time of data extraction (June 2014). In 381 (3.6%) of them, the date of CD diagnosis was missing, and therefore they were excluded. In 2049 (19.5%), the CD diagnoses were made between 2011 and 2013 and thus they were included in our study. Among these, 668 diagnoses occurred in 2011, 678 took place in 2012 and 703 in 2013. For the whole of Campania the incidence rate of CD was 11.8 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 11.3–12.3) and CD incidence was not statistically significantly different among the three years of analysis, even after adjusting for sex, age and province of residence (Table 1).

Table 1.

Incidence rate of coeliac disease in Campania by province of residence, sex, age at diagnosis and year of diagnosis during the period 2011–2013

| Cases | Person-yearsa | CD Incidence per 100,000 person-years (95% CI) | Crude IRR (95% CI) | Adjusted IRRb (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 2049 | 17,368,230 | 11.8 (11.3–12.3) | ||

| Years | |||||

| 2011 | 668 | 5,834,056 | 11.4 (10.6–12.3) | 1 | 1 |

| 2012 | 678 | 5,764,424 | 11.8 (10.9–12.7) | 1.03 (0.92–1.14) | 1.04 (0.93–1.16) |

| 2013 | 703 | 5,769,750 | 12.2 (11.3–13.1) | 1.06 (0.95–1.18) | 1.09 (0.98–1.21) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 608 | 8,420,803 | 7.2 (6.6–7.8) | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 1441 | 8,947,427 | 16.1 (15.3–16.9) | 2.23 (2.02–2.45) | 2.39 (2.18–2.63) |

| Age sub-groups | |||||

| <4 | 467 | 874,461 | 53.4 (48.7–58.5) | 1 | 1 |

| 5–19 | 592 | 2,989,882 | 19.8 (18.2–21.5) | 0.37 (0.33–0.42) | 0.37 (0.32–0.42) |

| 20–29 | 325 | 2,278,981 | 14.2 (12.7–15.9) | 0.27 (0.23–0.31) | 0.26 (0.23–0.31) |

| 30–49 | 532 | 5,145,380 | 10.3 (9.5–11.2) | 0.19 (0.17–0.22) | 0.19 (0.16–0.21) |

| 50–69 | 111 | 3,999,399 | 2.8 (2.3–3.3) | 0.05 (0.04–0.06) | 0.05 (0.04–0.06) |

| 70+ | 22 | 2,080,127 | 1.1 (0.6–1.6) | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) |

| Province of residence | |||||

| Naples | 1082 | 9,189,459 | 11.8 (11.1–12.5) | 1 | 1 |

| Salerno | 473 | 3,295,732 | 14.3 (13.1–15.7) | 1.22 (1.09–1.35) | 1.32 (1.19–1.47) |

| Caserta | 281 | 2,730,439 | 10.3 (9.1–11.6) | 0.87 (0.76–0.99) | 0.87 (0.77–1.0) |

| Avellino | 156 | 1,296,515 | 12.0 (10.2–14.1) | 1.02 (0.86–1.21) | 1.15 (0.97–1.36) |

| Benevento | 57 | 856,085 | 6.6 (5.0–8.6) | 0.56 (0.43–0.73) | 0.64 (0.49–0.84) |

ISTAT data 2011 and 2012 and 2013.

Adjusted for all other variables in the table.

Age and sex

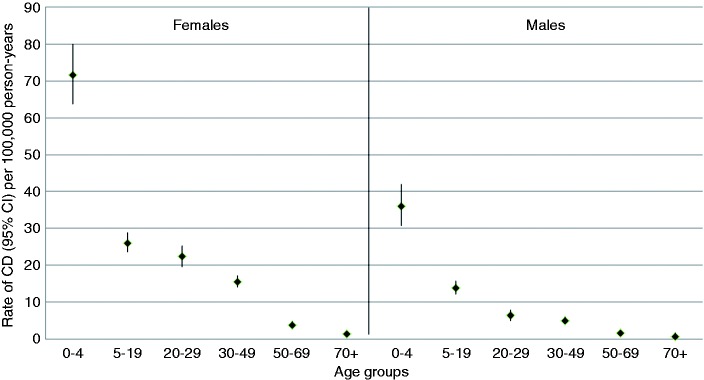

The rate of CD of 16.1 per 100,000 person-years was about 2.4 times higher in females than in males (IRR 2.39, 95% CI 2.18–2.64) after adjusting for year of diagnosis, age at diagnosis and province of residence. The highest incidence rate was found in people aged less than 4 years, in whom the CD incidence was 53.4 per 100,000 person-years. CD incidence rate progressively decreased as the age increased (LRT p for trend <0.001), with the lowest CD incidence rate found in people aged more than 70 years, in whom the incidence rate was 98% lower than that in children aged under 4 (IRR 0.02, 95% CI 0.01–0.03). As Figure 1 shows, the incidence rate of CD in females was higher than in males in each age group, with the highest difference between sexes in subjects aged 20–29, when the incidence of CD was 3.52 higher in females than in males (IRR 3.52, 95% CI 2.71–4.57).

Figure 1.

Incidence rates of CD per 100,000 person-years according to age group in females and males.

Dividing our population into two age groups, i.e. those who received their CD diagnosis during childhood (0–19 years) and during adulthood (>19 years), the incidence rate of CD was 27.4 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 25.8–29.1) in children and 7.3 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 6.8–7.8) in adults, corresponding to an CD incidence 73% lower in adults than in children (IRR 0.27, 95% CI 0.24–0.29).

As Table 1 shows, the highest CD incidence rate was found in Salerno, 14.3 per 100,000 person-years, which was 32% higher compared with that found in Naples after adjusting for calendar period, sex and age at CD diagnosis (IRR 1.32, 95% CI 1.19–1.47). The lowest rate was reported in Benevento, 6.6 per 100,000 person-years, which was 36% lower than the incidence found in Naples after adjusting for calendar period, sex and age at CD diagnosis (IRR 0.64, 95% CI 0.49–0.84). CD incidence rates were similar in Naples, Caserta and Avellino. Age was not an effect modifier in the relationship between provinces and CD (LRT p interaction=0.1) as the age distribution was similar across the provinces (Table 2).

Table 2.

Incidence rate of coeliac disease in Campania by age at diagnosis in each province of residence during the period 2011–2013

| Cases | Person- yearsa | CD Incidence per 100,000 person- years (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NA | Age groups | |||

| <4 | 271 | 492,272 | 55 (48.7–62) | |

| 5–19 | 331 | 1,666,055 | 19.9 (17.8–22.1) | |

| 20–29 | 162 | 1,220,185 | 13.3 (11.3–15.5) | |

| 30–49 | 256 | 2,724,817 | 9.4 (8.3–10.6) | |

| 50–69 | 51 | 2,101,400 | 2.4 (1.8–3.2) | |

| 70+ | 11 | 984,730 | 1.1 (0.6–2) | |

| SA | Age groups | |||

| <4 | 101 | 149,464 | 67.6 (55–82.1) | |

| 5–19 | 129 | 517,908 | 24.9 (20.8–29.9) | |

| 20–29 | 69 | 422,656 | 16.3 (12.7–20.7) | |

| 30–49 | 131 | 967,082 | 13.5 (11.3–16.1) | |

| 50–69 | 34 | 782,476 | 4.3 (3–6.1) | |

| 70+ | 9 | 456,146 | 2 (0.9–3.7) | |

| CE | Age groups | |||

| <4 | 54 | 143,526 | 37.6 (28.2–49.1) | |

| 5–19 | 74 | 482,964 | 15.3 (12.0–19.2) | |

| 20–29 | 53 | 366,374 | 14.5 (10.8–18.9) | |

| 30–49 | 86 | 830,747 | 10.3 (8.2–12.8) | |

| 50–69 | 13 | 607,149 | 2.1 (1.1–3.6) | |

| 70+ | 1 | 299,679 | 0.3 (0.008–1.8) | |

| AV | Age groups | |||

| <4 | 24 | 53,986 | 44.4 (28.5–66.1) | |

| 5–19 | 44 | 194,527 | 22.6 (16.4–30.3) | |

| 20–29 | 33 | 163,487 | 20.2 (13.9–28.3) | |

| 30–49 | 42 | 378,442 | 11.1 (8.0–15.0) | |

| 50–69 | 12 | 306,644 | 3.9 (2.0–6.8) | |

| 70+ | 1 | 199,429 | 0.5 (0.01–2.7) | |

| BN | Age groups | |||

| <4 | 17 | 35,213 | 48.3 (28.1–77.3) | |

| 5–19 | 14 | 128,428 | 10.9 (5.9–18.3) | |

| 20–29 | 8 | 106,279 | 7.5 (3.2–14.8) | |

| 30–49 | 17 | 244,292 | 6.9 (4.0–11.1) | |

| 50–69 | 1 | 201,730 | 0.5 (0.01–2.7) | |

| 70+ | 0 | 140,143 | 0 |

ISTAT data 2011 and 2012 and 2013.

NA: Naples; SA: Salerno; CE: Caserta; AV: Avellino; BN: Benevento

Mode of diagnosis and clinical presentation at diagnosis

Table 3 shows the mode of CD diagnosis according to age group. The diagnosis was based on the combination of positive antitransglutaminase IgA and Marsh 3 on histological evaluation of the small bowel in 1732 subjects (84.6%); all 83 patients with Marsh 1 and the 63 patients with Marsh 2 on histological evaluation had positive serology, were HLA-DQ2 or DQ8 positive and were symptomatic. Endoscopy was not performed in 146 people (7.1%) and in particular among people aged less than 4 and more than 70 years. Among the 146 patients who did not undergo endoscopy, 105 children were included into a validated long-term trial for the ESPGHAN criteria, five women were pregnant at the time of CD diagnosis, three children were affected by Down’s Syndrome, two had undergone skin biopsy and 20 cases refused the procedure (in the other subjects the reasons were: very old age and anti-coagulant therapy, respiratory diseases, severe neurological diseases). In 25 cases (1.2%) the diagnosis was made in patients with negative CD serology but positive histology (Marsh 3 lesion) and HLA-DQ2 positivity. Among them, IgA deficiency was clearly reported in six subjects.

Table 3.

Modes of CD diagnosis in Campania register according to the age groups

| Only Marsh 3 (%) | Ab + Marsh 1 (%) | Ab + Marsh 2 (%) | Ab + Marsh 3 (%) | Ab + HLA + Symptoms (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All ages | 25 (1.2) | 83 (4) | 63 (3.1) | 1732 (84.6) | 146 (7.1) |

| Age groups | |||||

| <4 | 0 | 16 (3.4) | 6 (1.3) | 358 (76.7) | 87 (18.6) |

| 5–19 | 2 (0.3) | 30 (5.1) | 12 (2) | 508 (85.8) | 40 (6.8) |

| 20–29 | 10(3.1) | 12 (3.7) | 11 (3.4) | 288 (88.6) | 4 (1.2) |

| 30–49 | 7 (1.3) | 21 (3.9) | 27 (5.1) | 468 (88) | 9 (1.7) |

| 50–69 | 5 (4.5) | 3 (2.7) | 4 (3.6) | 97 (87.4) | 2 (1.8) |

| 70+ | 1 (4.6) | 1 (4.6) | 3 (13.6) | 13 (59) | 4 (18.2) |

Ab: antitransglutaminase and antiendomysial antibodies

Restricting our main analysis to patients with positive antitransglutaminase IgA antibodies and Marsh 3 lesion on histological evaluation (1732), we found an incidence rate of CD of 10 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 9.5–10.4).

Table 4 summarizes the clinical presentation, following the Oslo criteria20: 60.8% of our population reported at least one symptom at the time of CD diagnosis (classical and non-classical symptoms), 7.5% were investigated for anaemia without any symptoms, while 13% were asymptomatic (no symptoms/no anaemia). In 18.7% of cases clinicians did not report patients’ clinical history in the register. Some 55 (2.7%) had dermatitis herpetiformis at the time of CD diagnosis. Among them, 14 patients had no other signs or symptoms of CD. During the study period, two women received the CD diagnosis at the time of surgery for intestinal lymphoma and small bowel carcinoma, respectively.

Table 4.

Modes of CD clinical presentation

| Clinical presentation | Classical presentation (malabsorption symptomsa) (%) | Non-classical presentation (other symptomsb) (%) | Non-classical presentation (only anaemia) (%) | Asymptomatic (%) | Missing (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All age | 813 (39.7) | 433 (21.1) | 154 (7.5) | 266 (13) | 383 (18.7) |

| <4 | 207 (44.3) | 68 (14.7) | 25 (5.3) | 44 (9.4) | 123 (26.3) |

| 5–19 | 174 (29.4) | 123 (20.8) | 43 (7.3) | 114 (19.2) | 138 (23.3) |

| All children | 381 (36) | 191 (18) | 68 (6.4) | 158 (15) | 261 (24.6) |

| 20–29 | 148 (45.5) | 82 (25.2) | 22 (6.8) | 37 (11.4) | 36 (11.1) |

| 30–49 | 217 (40.7) | 138 (25.9) | 52 (10) | 63 (11.8) | 62 (11.6) |

| 50–69 | 55 (49.6) | 20 (18) | 9 (8.1) | 6 (5.4) | 21 (18.9) |

| 70+ | 12 (54.6) | 2 (9.1) | 3 (13.6) | 2 (9.1) | 3 (13.6) |

| All adults | 432 (43.6) | 242 (24.5) | 86 (8.7) | 108 (10.9) | 122 (12.3) |

At least one among: diarrhoea, weight loss, failure to thrive.

bAt least one among: lack of appetite, vomit, meteorism, abdominal pain, constipation, asthenia, dyspepsia.

Discussion

The overall incidence of CD in Campania was 11.8 per 100,000 person-years between 2011 and 2013, with the highest incidence observed in females (16.1 per 100,000 person-years) compared with males and in children aged 0–4 years (53.4 per 100,000 person-years) compared with older patients. The incidence rate decreased as age increased similarly in each province of residence. CD incidence was roughly similar in Naples, Salerno, Caserta and Avellino (range: 10.3–14.3 per 100,000), but was about half in Benevento (6.6 per 100,000). More than 80% of our study population was diagnosed by the combination of positive serology and histology, and more than half of the patients were symptomatic at the time of the CD diagnosis.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study which uses a regional register based on certification dedicated to CD where the secondary centres include all newly diagnosed coeliac patients with details on demographic aspects and mode of diagnosis across a region of the size of Campania, i.e. approximately 6 million inhabitants. Moreover, thanks to the recent years analysed and the large sample size, our study provides both contemporary and reasonably precise estimates. Also, having all information on the mode of diagnosis, the risk of false positives occurring in our population is low.

Some limitations of our study need to be considered. The CeliaDB was instituted in 2006, but only at the end of 2010 were all secondary centres invited to use the database. Therefore, we were not able to present either a trend of CD incidence over time or an accurate prevalence of CD in Campania, since the CD diagnoses performed before 2010 were retrospectively included in the register only by a few centres. Moreover, we cannot exclude an underestimation of our overall and age/sex-specific incidence rates in the different provinces of Campania, possibly due to either a different use of the register and a different CD awareness between paediatricians and gastroenterologists or among the centres of the different provinces. We reported only 6.5% of diagnoses in patients over the age of 50 years, which is lower compared with that reported from the previous literature.11,21 This may be related to the fact that clinical presentation in adults is more frequently characterized by non-classical presentation,20 often without any gastrointestinal symptoms22 and therefore still not recognized by GPs in our region, rather than a true difference in the incidence.

In addition, there is an unequal distribution of CD centres among the provinces, with the highest number of centres in Naples and just one active adult centre in Avellino and Benevento; this could influence the number of people who are routinely tested for CD. Five centres were considered to be inactive as they registered fewer than 10 patients in the study period; however, we think we may only have lost a few patients because of this, since next to each of these five centres there is always a fully active coeliac centre where patients can ask for consultation and get the CD certificate. Finally, in around 18% of our population, symptoms and signs at the time of diagnosis were missing and this could have compromised our findings on the clinical presentations; however, we tried to avoid this bias, considering patients with missing data as an independent group.

Comparison with previous reports

The CD incidence estimates reported in the 2000s vary fairly widely among the available studies, probably due to differences in study populations and study designs. A population-based study from the UK11 recently reported an overall CD incidence of 13.8 per 100,000 person-years from 1990 to 2011, with a near four-fold increase in the incidence during the study period, reaching a rate of 19.14 per 100,000 person-years in 2011, which is higher than the overall incidence we found in 2011 (11.4 per 100,000 person-years). Similarly, a population-based study in Olmsted Country, Minnesota,2 reported an overall age- and sex-adjusted incidence of CD of 17.3 per 100,000 person-years in 2008–2010. An even higher incidence rate was reported in a study conducted on adults in Finland. Virta et al.23 identified all coeliac patients aged over 16 years, reporting an annual age-adjusted CD incidence of 39.3 per 100,000 people in 2004–2006 (5020 new cases). Conversely, an American study4 reported a lower incidence rate of CD in adults compared with our findings. The authors used the clinical data of all subjects who were active duty US military personnel serving between 1999 and 2008.4 The authors reported a total of 455 cases of CD between 1999 and 2008, with an overall incidence of 3.55 per 100,000 person-years and in particular a CD incidence of 6.5 per 100,000 person-years in 2008. However, this study was not representative of the general population, since individuals with chronically ill health generally are not admitted into the military, and younger and older people were excluded. In children the highest CD was reported by a Swedish study9 which reported a CD incidence of 44 per 100,000 person-years in 2003 in subjects younger than 15. In particular, the authors found an incidence of 66 per 100,000 in children aged 0–1.9 years, 35 per 100,000 person-years in children aged 2–4.9 years, and 23 per 100,000 person-years in children aged 5–14.9 years, during the whole period of evaluation (1998–2003). Conversely, other previous studies conducted on children reported a lower CD incidence rate compared with our findings.5,6,24 Recently, Dixit et al.25 have confirmed a higher incidence of CD in females than in males, already known in the previous literature,26–28 but in particular the authors have described a lower proportion of newly diagnosed patients among young men (age 18–29 years) than in any other age groups. Similarly, we reported the highest difference between sexes in subjects aged 20–29.

Interpretation

The variation in CD incidence we have found among the five provinces of Campania is likely to be caused by patient and physician behaviour, and a different awareness of CD among provinces. For example, Benevento includes more rural areas compared with the other Campania provinces, so we can imagine that subjects tend to visit their doctors only in case of severe clinical conditions, making it more difficult to capture subclinical and non-classic forms of CD. The different CD incidence rates between children and adults should stimulate new coeliac awareness programmes based on teaching days and local meetings with general practitioners, looking at adults. Finally, the gender disparity, in particular in young subjects, may be related to the evidence that women at this age often attend the doctor due to fertility-related issues, and moreover, those who are menstruating are likely to show evidence of anaemia more commonly than men.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that this condition is common among children in Italy and that there are likely to be opportunities to improve case finding and diagnosis for adults in areas outside large urban populations, of which there are many in the South of Italy. Our use of a prospectively collected web-based coeliac database to describe this epidemiology indicates the potential value to researchers in the future who have an interest in the causes and consequences of CD.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Assessorato Sanità of the Campania Region for continuous support to the Celiac network (progetto Malattie Rare). They are grateful also to Eliana Rispoli and Savio Pisa for their expertise in management of CeliaDB and the education provided to all participating centres.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

None declared

References

- 1.Kang J, Kang A, Green A, et al. Systematic review: Worldwide variation in the frequency of coeliac disease and changes over time. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013; 38: 226–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ludvigsson JF, Rubio-Tapia A, van Dyke CT, et al. Increasing incidence of celiac disease in a north American population. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 818–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White LE, Merrick VM, Bannerman E, et al. The rising incidence of celiac disease in Scotland. Pediatrics 2013; 132: e924–e931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riddle MS, Murray JA, Porter CK. The incidence and risk of celiac disease in a healthy US adult population. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 1248–1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurley JJ, Lee B, Turner JK, et al. Incidence and presentation of reported coeliac disease in Cardiff and the Vale of Glamorgan: The next 10 years. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 24: 482–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dydensborg S, Toftedal P, Biaggi M, et al. Increasing prevalence of coeliac disease in Denmark: A linkage study combining national registries. Acta Paediatr 2012; 101: 179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angeli G, Pasquini R, Panella V, et al. An epidemiologic survey of celiac disease in the Terni area (Umbria, Italy) in 2002–2010. J Prev Med Hyg 2012; 53: 20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ress K, Luts K, Rägo T, et al. Nationwide study of childhood celiac disease incidence over a 35-year period in Estonia. Eur J Pediatr 2012; 171: 1823–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsson C, Stenlund H, Hörnell A, et al. Regional variation in celiac disease risk within Sweden revealed by the nationwide prospective incidence register. Acta Paediatr 2009; 98: 337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanzini A, Lanzini A, Villanacci V, et al. Epidemiological, clinical and histopathologic characteristics of celiac disease: Results of a case-finding population-based program in an Italian community. Scand J Gastroenterol 2005; 40: 950–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.West J, Fleming KM, Tata LJ, et al. Incidence and prevalence of celiac disease and dermatitis herpetiformis in the UK over two decades: Population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109: 757–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciacci C, De Florio M. Evaluation of an instrument for the surveillance of adult gluten intolerance diagnosis: Report of the first year of activity of the Campania Celiac Network for Adult Celiac Disease. Dig Liver Dis 2007; 39: 703–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Regione Campania. Available at: www.regione.campania.it.

- 14.Biagi F, Schiepatti A, Malamut G, et al. PROgnosticating COeliac patieNts SUrvivaL: The PROCONSUL Score. PloS one 2014; 9: e84163–e84163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biagi F, Marchese A, Ferretti F, et al. A multicentre case control study on complicated coeliac disease: Two different patterns of natural history, two different prognoses. BMC Gastroenterol 2014; 14: 139–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biagi F, Gobbi P, Marchese A, et al. Low incidence but poor prognosis of complicated coeliac disease: A retrospective multicentre study. Dig Liver Dis 2014; 46: 227–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Celiac DB – Registro Regionale per lo studio della malattia celiaca. Available at: www.registrocampaniaceliachia.org.

- 18.Marsh M. Gluten, major histocompatibility complex, and the small intestine. A molecular and immunobiologic approach to the spectrum of gluten sensitivity (‘celiac sprue'). Gastroenterology 1992; 102: 330–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The National Institute for Statistics (ISTAT). Available at: www.istat.it/en/.

- 20.Ludvigsson JF, Leffler DA, Bai JC, et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut 2013; 62: 43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vilppula A, Kaukinen K, Luostarinen L, et al. Increasing prevalence and high incidence of celiac disease in elderly people: A population-based study. BMC Gastroenterol 2009; 9: 49–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tursi A, Giorgetti G, Brandimarte G, et al. Prevalence and clinical presentation of subclinical/silent celiac disease in adults: An analysis on a 12-year observation. Hepatogastroenterology 2000; 48: 462–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Virta LJ, Kaukinen K, Collin P. Incidence and prevalence of diagnosed coeliac disease in Finland: Results of effective case finding in adults. Scand J Gastroenterol 2009; 44: 933–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White LE, Bannerman E, McGrogan P, et al. Childhood coeliac disease diagnoses in Scotland 2009–2010: The SPSU project. Arch Dis Child 2013; 98: 52–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dixit R, Lebwohl B, Ludvigsson JF, et al. Celiac disease is diagnosed less frequently in young adult males. Dig Dis Sci 2014, pp. 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green PHR, Stavropoulos SN, Panagi SG, et al. Characteristics of adult celiac disease in the USA: Results of a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96: 126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ciacci C, Cirillo M, Sollazzo R, et al. Gender and clinical presentation in adult celiac disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 1995; 30: 1077–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray JA, Dyke CV, Plevak MF, et al. Trends in the identification and clinical features of celiac disease in a North American community, 1950–2001. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003; 1: 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]