Abstract

PI3K-AKT-mTOR and Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK are the most commonly altered oncogenic pathways in solid malignancies. There has been a lot of enthusiasm to develop inhibitors to these pathways for cancer therapy. Unfortunately, the antitumor activities of single-agent therapies have generally been disappointing, excluding B-Raf mutant melanoma and renal cell cancer. Preclinical studies have suggested that concurrent targeting of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR and Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathways is an active combination in various solid malignancies. In the current work, we review the preclinical data of the PI3K and MEK dual targeting as a cancer therapy and the results of early-phase clinical trials, and propose future directions.

Keywords: inhibition, MEK, PI3K, solid tumors, targeted therapy

Introduction

Constitutive activation of oncogenic pathways occurs in cancers with very high frequency. It is thought to be a central factor behind the hallmarks of cancer phenotype such as cell cycle progression, inhibition of apoptosis and reprogramming of metabolism. In solid malignancies, the PI3K-AKT-mTOR and Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathways are thought to play a central role in transmitting these oncogenic signals. Genetic alterations, such as receptor mutations or amplifications, or mutations in intermediate signal transducers, can lead to the constitutive activation of the pathways. The high frequency of genetic alterations causing constitutive activation of PI3K-AKT or Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK and the addiction of cancer cells on their signals have generated enthusiasm to develop pathway inhibitors.

Considering the central role of the pathways in transmitting upstream oncogenic signals, inhibition of these pathways could be an effective therapy in various cancer genotypes [Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011]. Despite the undisputed rationale of this approach, the clinical activity of the single pathway inhibition has been limited to B-Raf inhibition in B-Raf mutant melanoma and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibition in renal cell cancer [Solit et al. 2006; Hudes et al. 2007; Motzer et al. 2008]. The effectiveness of single pathway inhibition could be suppressed by de novo dependency on multiple signaling pathways or feedback activation of other signaling pathways [Faber et al. 2009; Chandarlapaty et al. 2010]. This has led to studies combining phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mTOR and Raf/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) inhibitors.

PI3K pathway

PI3Ks are divided by structure, regulation and lipid substrate specificity into three subclasses: class I, II and III. Of the three subclasses of PI3K, class I has been related to cancer. Class I PI3K is composed of a p110 catalytic subunit, coded by PIK3CA, PIK3CB, PIK3CD and PIK3CG genes, and a p85 regulatory subunit. The kinase activity of p110 is regulated downstream of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) by the binding of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins to its regulatory p85 subunit, resulting in reduction of its autoinhibitory activity. Furthermore, p110 has a Ras motif in which activated Ras proteins can bind leading to optimal lipid kinase activity. Activated PI3K produce phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3), which can activate downstream targets, such as AKT which further activates mTOR [Engelman et al. 2006].

The PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway has an important role in cell survival and proliferation, and constitutive activation of the pathway is common in solid malignancies. The hyperactivation of the pathway is most frequently caused by the activation of RTKs, somatic mutations in specific signaling components of the pathway such as PIK3CA, or the loss of PTEN tumor suppressor. PIK3CA mutations are frequently detected in endometrial, breast, lung, urinary tract, colorectal, gliomas and gastric cancers [Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, 2008, 2012a, 2012b, 2012c, 2013, 2014a, 2014b, 2014c] while amplification of the gene is commonly seen in head and neck, lung, gastric and ovarian cancers [Lin et al. 2005; Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, 2011, 2012a, 2014a]. Genetic PTEN loss occurs recurrently in endometrial, prostate, gliomas, lung and breast cancers [Cancer Genome Atlas Research, 2008, 2012, 2012, 2013; Bismar et al. 2011] (Table 1, Figure 1).

Table 1.

Frequencies of genetic alterations leading to activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR and RAS-Raf-MEK-ERK pathways in specific solid cancers.

| Gene | Cancer | Alteration |

|---|---|---|

| PI3KCA | Mutation | |

| Endometrial | 51% | |

| Breast | 25% | |

| Lung (SQC) | 16% | |

| Urinary tract | 15% | |

| Glioma | 15% | |

| Colon | 12% | |

| Gastric | 12% | |

| PI3KCA | Amplification | |

| Head and neck | 43% | |

| Ovarian | 18% | |

| Lung (SQC) | 12% | |

| Gastric | 12% | |

| PTEN | Inactivation | |

| Endometrial | 59% | |

| Prostate | 42% | |

| Glioma | 36% | |

| Lung (SQC) | 15% | |

| Breast | 10% | |

| K-RAS | Mutation | |

| Pancreatic | 95% | |

| Colorectal | 43% | |

| Lung (AC) | 32% | |

| Endometrial | 18% | |

| NF1 | Inactivation | |

| Glioma | 14% | |

| Sarcoma | 11% | |

| Lung (AC) | 11% | |

| B-Raf | Mutation | |

| Melanoma | 66% | |

| Thyroid (PAP) | 36% |

AC, adenocarcinoma; PAP, papillary; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

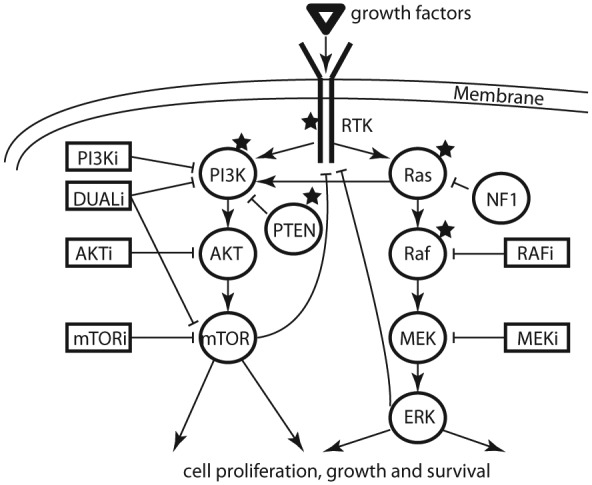

Figure 1.

Signaling of PI3K-AKT-mTOR and Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathways and inhibitors currently tested in cancer clinical trials. Signaling molecules are drawn with circles and inhibitors with boxes. Stars indicate signaling molecules that are frequently altered in solid malignancies.

AKTi, AKT inhibitor; DUALi, dual PI3K; ERK, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase; MEKi, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibitor; mTORi, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor; NF1, neurofibromin; PI3Ki, phosphoinositide-3 kinase inhibitor; RAFi, RAF inhibitor; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase.

PI3K-pathway inhibitors

Several small molecular inhibitors targeting the PI3K pathway have been developed, including dual PI3K–mTOR-, PI3K-, AKT- and mTOR inhibitors. Allosteric, rapalog analog mTOR inhibitors were the first to enter clinical trials but, unfortunately, showed activity only in a limited number of solid tumor types. Limited clinical activity of the rapalogs has been suggested to result from various drug-induced feedback loops leading to mTORC2-IRS-1 mediated hyperactivation of PI3K-AKT [O’Reilly et al. 2006].

Rapalog-induced PI3K-AKT hyperactivation has led to the development of upstream inhibitors, which could overcome the hyperactivation and have more clinical activity [Wander et al. 2011]. These upstream inhibitors include dual PI3K-mTOR (BEZ235), pan PI3K (GDC-0941 and BKM120) and AKT inhibitors (MK-2206, GDC-0068) (Table 2). Of these drugs, most fall into adenosine triphosphate (ATP) competitive class, while both ATP and non-ATP competitive AKT inhibitors do exist. Recently, a newer generation of inhibitors has entered clinical trials including isoform specific PI3K inhibitors and ATP competitive inhibitors of mTORC1/2.

Table 2.

Examples of PI3K and MEK inhibitors tested in clinic.

| PI3K inhibitors | |

| GDC-0941 | GDC-0941 is a potent and selective, orally bioavailable class I PI3K inhibitor which inhibits the growth of a wide of human tumor cell lines. The compound has shown strong inhibition of the growth of IGROV-1 ovarian cancer and U87M glioblastoma xenografts. GDC-0941 has already been tested in clinical trials. |

| BEZ235 | The imidazo[4,5-c]quinoline derivative BEZ235 is a dual PI3K-mTOR inhibitor. The compound blocks abnormal PI3K activation causing G1 cell cycle arrest. In vivo studies showed BEZ235 to be well tolerated and suitable for combinations studies. The inhibitor has entered clinical trials. |

| BKM120 | The 2-morpholino pyrimidine derivative BKM120 is a selective pan-PI3K inhibitor which inhibits all four class I isoforms of PI3K. The compound preferentially inhibits tumor cells with PIK3CA mutations over KRAS and PTEN mutated tumor cells. The biologic, pharmacological and preclinical safety profile of BKM120 h support its clinical use and the compound has been tested in phase II clinical trials with cancer patients. |

| MEK inhibitors | |

| CI-1040 | CI-1040 (PD-184352) is a specific small-molecule drug that inhibits MEK1/MEK2. The compound has been suggested to act as an allosteric inhibitor of MEK since it is known not to compete with the binding of ATP or protein substrates. CI-1040 blocks ERK phosphorylation and inhibits the growth of multiple human tumor cell lines as well as tumor growth in xenograft models. It has been shown that the cell growth inhibitory effect of CI-1040 is rapidly reversed after it is removed from the growth media. CI-1040 was the first MEK inhibitor to enter clinical trials where it was shown to be well tolerated, but was found to have insufficient antitumor activity in patients. PD-0325901 is a CI-1040 derivate with higher solubility and improved pharmacological properties currently being tested in clinical trials. |

| GDC-0973 | GDC-0973 (XL518) is methanone derived, potent, orally bioavailable MEK1/2 inhibitor which has a 100-fold MEK1 selectivity over MEK2. The compound has shown tumor growth inhibition in BRAF and KRAS mutated cancer cell lines in vivo and in vitro. |

| Trametinib | Trametinib (GSK1120212), a selective MEK1 and MEK2 inhibitor, dephosphorylates phosphorylated MEK and also stabilizes the unphosphorylated form, thereby blocking the downstream signaling. At the moment, it is the only MEK inhibitor, which has showed promising results in phase III clinical trials. |

| Pimasertib | Pimasertib (AS703026, MSC1936369B) is an orally available, selective second generation inhibitor of MEK1/2 which binds ATP non-competitively to the distinctive allosteric site of MEK1/2 causing G0–G1 cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Pimasertib has been shown to cause significant tumor regression in human multiple myeloma and KRAS mutated colorectal cancer xenografts. |

ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ERK, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; PI3K, phosphoinositide-3 kinase.

Currently, only the rapalog inhibitors of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway have entered the clinic for the treatment of cancer. Rapalogs have previously been widely tested in various solid malignancies but have shown clinical activity in a limited number of indications. Everolimus has been approved for renal cell cancer (RCC) and neuroendocrine cancers as a single-agent and for breast cancer in combination with hormonal therapy [Motzer et al. 2008; Yao et al. 2011; Baselga et al. 2012]. Another mTOR inhibitor, temsirolimus, has also been approved to the treatment of RCC [Hudes et al. 2007]. In contrast to most solid malignancies, activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) is a central oncogenic event in RCC, which might relate to the clinical activity of the rapalogs in this disease. mTOR is an indirect upstream regulator of HIF-1α and therefore may represent an easier clinical target for mTOR inhibition compared with most solid malignancies in which the RTK pathways upstream of mTOR dominate in oncogenesis [Bellmunt et al. 2013].

Numerous clinical trials are testing the safety and efficiency of dual PI3K-mTOR, PI3K and AKT inhibitors in various solid malignancies. Treatment with these inhibitors seems to be well tolerated with dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) from hyperglycemia, rash, gastrointestinal side effects and stomatitis [Dienstmann et al. 2011; Bran and Siu, 2012]. Various methods have been used to analyze the dose–effect relationship of these drugs, such as the measurement of biomarkers pAKT and pS6 in cells and tissues. With the maximum tolerated dose (MTD), inhibitors induce 30–90% inhibition of pAKT and/or pS6 biomarkers [Bendell et al. 2011; Moreno Garcia et al. 2011].

Based on early-phase clinical trials, the single-agent clinical activity of PI3K-mTOR, PI3K and AKT inhibitors seems to be modest in unselected solid malignancies. The drugs appear to be more active in tumors bearing genetic alterations in PIK3CA or PTEN, but no clear correlation between genotype and response have been established [Brachmann et al. 2009; Weigelt et al. 2011]. General lack of clinical benefit could result from various factors, such as limited target inhibition or feedback activation of other pathways. As low as 30% target inhibition has been reported in clinical trials and it is unlikely that this magnitude of inhibition could result in clinical activity. Furthermore, feedback activation of other pathways has been reported in preclinical studies but general landscape of this phenomenon has not been characterized. Preclinical studies with PI3K and AKT inhibitors have shown that these drugs induce feedback activation of the extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER) family, which at least partly results in decreased anticancer activity [Chandarlapaty et al. 2010; Serra et al. 2011]. Similar feedback activation phenomenon of the ERK and HER family has also been recapitulated in clinical trials of the agents [Yan et al. 2013].

Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathway

The binding of cytokines, growth factors or mitogens to their receptors causes activation of the Shc/Grb2/SOS coupling complex, which in turn stimulates the inactive Ras (H-, K, N-isotypes). Stimulated Ras exchanges guanosine diphosphate (GDP) to guanosine triphosphate (GTP) and undergoes conformational change to active stage. Ras proteins have an intrinsic GTPase activity, required for inactivation of the GTP bound active state. The GTPase activity of Ras protein is strongly enhanced by binding of GTPase proteins such as nuclear factor 1 (NF1). Ras proteins have multiple downstream targets, with Raf kinase being the most well characterized. Raf kinase activates MEK1/2, which catalyzes activation of ERK1/2. Activation of ERK1/2 further phosphorylates a series of downstream targets involved in various cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, cell survival and angiogenesis.

Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK hyperactivation is very frequently evident in solid malignancies and is transforming in multiple cancer models. In cancers, activation of Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK occurs through various mechanisms. Hyperactivation of RTKs can induce constitutive activation of the pathway. Furthermore, genetic alterations in the pathway members are common mechanisms behind the hyperactivation. Ras mutations or loss of NF1 cause activation of the pathway at the level of Ras. Ras mutations are commonly found in pancreatic, colorectal, lung, and endometrial cancers [Almoguera et al. 1988; Cancer Genome Atlas Network, 2012b, 2013, 2014c] and NF1 mutations are seen in gliomas, sarcomas and lung cancers [Cancer Genome Atlas Research, 2008, 2014c; Barretina et al. 2010]. Mutations in the Raf genes are another level where genetic constitutive activation occurs repeatedly, while MEK or ERK mutations are rare. Raf mutations are frequent in melanoma and thyroid cancers [Davies et al. 2002; Kimura et al. 2003] (Table 1, Figure 1).

Inhibitors of Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathway

Considerable efforts have been made to develop Ras targeted drugs, such as farnesyl transferase inhibitors, but so far clinical trials have been unsuccessful [Sousa et al. 2008]. Various Raf inhibitors have been developed, of which sorafenib was the first to enter the clinic in the treatment of renal and hepatocellular cancers [Escudier et al. 2007; Llovet et al. 2008]. Even though sorafenib is an inhibitor of wildtype and mutant B-Raf, its clinical activity is limited in B-Raf driven cancers such as melanoma [Eisen et al. 2006; Gollob et al. 2006]. It is likely that the MTD of sorafenib does not lead to meaningful inhibition of mutant B-Raf [<10% by phosphorylated ERK (pERK) assessment] [Davies et al. 2012].

The clinical activity of sorafenib in renal and hepatocellular cancers is largely related to the other kinases inhibited by it such as VEGFR2-3, FGFR-1, PDGFR-b, Flt-3 and c-Kit [Wilhelm et al. 2008]. Later, inhibitors preferentially targeting mutant B-Raf, such as vemurafenib and dabrafenib, were developed. These inhibitors induce marked downregulation of B-Raf signaling and >80% inhibition of pERK in tumors correlates with responses [Bollag et al. 2010]. Dabrafenib and vemurafenib have significant clinical activity in B-Raf mutant melanoma and have been approved for this indication [Chapman et al. 2011; Hauschild et al. 2012]. Conversely, mutant B-Raf targeted inhibitors paradoxically hyperactivate MEK/ERK signaling in cells with wildtype protein and therefore do not have antitumor activity in B-Raf wildtype tumors. Paradoxical hyperactivation of signaling by B-Raf inhibitors has been linked to increased C-Raf dimerization-mediated activation of downstream targets MEK/ERK [Poulikakos et al. 2010]. Paradoxical MEK/ERK hyperactivation in patients undergoing B-Raf inhibitor therapy can be manifested by presentation of skin squamous cell cancers, keratoachantomas or even leukemias. These clinical manifestations strongly associate with presence of Ras mutations in them [Callahan et al. 2012; Su et al. 2012].

MEK inhibitors are classed into ATP competitive and ATP non-competitive agents. Most of the known MEK inhibitors fall into the latter category, and hence are not directly competing for the ATP-binding site but bind to a unique allosteric binding site adjacent to the ATP binding site. Thus, non-ATP competitive MEK inhibitors have high specificity for the target [Wallace et al. 2005]. CI-1040 was the first allosteric MEK1/2 inhibitor to enter clinical trials. CI-1040 was shown to be well tolerated but possessed insufficient antitumor activity in patients [Rinehart et al. 2004]. Most of the newer MEK inhibitors following CI-1040 share a similar chemical structure but are more potent inhibitors of the target. These inhibitors include agents such as trametinib, selumetinib, GDC-0973 and BAY869766. Treatment with these agents seems to be well tolerated with DLTs from rash, diarrhea and periferial edema [Adjei et al. 2008; Bennouna et al. 2011; Infante et al. 2012; Lorusso et al. 2012]. Various methods have been used to analyze the dose–effect relationship of the drugs, such as measurement of pERK levels in normal tissues and tumors. With MTDs, these inhibitors induce >80% reduction of pERK levels in various tissues [Adjei et al. 2008; Weekes et al. 2013]. Even if true with B-Raf inhibitors, it is unknown whether MEK inhibitor induced target inhibition of >80% surpasses the required level for cytotoxicity.

MEK inhibitors are currently tested as single agents or in combination with other targeted agents or chemotherapy. Single-agent activity has been seen in Ras and Raf mutant patients [Zimmer et al. 2014]. The most promising results are in thyroid cancer in combination with I-131 and in B-Raf mutant melanoma in combination with B-Raf inhibitors [Flaherty et al. 2012; Ho et al. 2013] (Table 2).

Dual inhibition

Even though PI3K-AKT-mTOR and Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK are the most commonly altered signaling pathways in solid malignancies, the clinical efficiency of single pathway inhibitors has generally been disappointing with some exclusion such as B-Raf mutant melanoma or renal cell cancer. Cancers can be de novo dependent concurrently on these two parallel pathways and cross-signaling of the pathways is also evident, such as direct K-Ras mediated activation of PI3K [Faber et al. 2009; Chandarlapaty et al. 2010]. Many in vivo and in vitro studies have shown that PI3K-AKT-mTOR and Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathways regulate each other’s activity through feedback mechanisms, i.e. MEK inhibition causes PI3K/Akt activation via ERBB receptors [Turke et al. 2012]. Furthermore, PI3K-AKT-mTOR and Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK have also been shown to coregulate shared downstream targets including forkhead box transcription factor class O (FOXO), Bcl-2-associated death promoter (BAD) and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) [Mendoza et al. 2011]. The interaction of the parallel PI3K-AKT-mTOR and Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK signaling pathways is thought to explain the inefficiency of single-agent treatments in most malignancies and gives rationale for the concurrent targeting of both pathways.

To date, most efforts to dual target the PI3K-AKT-mTOR and Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathways have been carried out with a combination of PI3K and MEK inhibitors. However, many studies with mTOR and AKT inhibitors do also exist. PI3K targeting agents are theoretically the most potent inhibitors of the pathway since they lack the downstream feedback activation of mTOR inhibitors [O’Reilly et al. 2006]. Furthermore, PI3K is also known to have other important, cancer-associated downstream targets than AKT making PI3K inhibitors more potent than AKT inhibitors from that perspective [Vasudevan et al. 2009]. Allosteric MEK inhibitors are highly specific for their targets and are known to also induce high inhibition of the pathway in patients [Adjei et al. 2008; Weekes et al. 2013], while the current RAF inhibitors are significantly less effective in inhibiting downstream signaling in tumors with wildtype Raf.

Preclinical models have shown that dual targeting with PI3K and MEK inhibitors possesses antitumor activity in various cancer models and genotypes. Activity is also seen in difficult to treat genotypes, such as Ras mutant tumors and basal like breast cancer [Engelman et al. 2008; Hoeflich et al. 2009; Sos et al. 2009]. Even though Ras is generally thought to be a direct upstream activator of Raf, responses to MEK inhibitors are variable in Ras mutant cancer models. Variable responses could be explained by Ras mediated activation of other signaling pathways such as PI3K and, therefore, dual targeting with MEK and PI3K inhibitors is potentially more effective [Mendoza et al. 2011]. Some models, such as basal-like breast cancer, have shown that treatment with MEK inhibitors induces feedback activation of RTKs which signal downstream to PI3K and therefore, dual targeting is more active [Hoeflich et al. 2009]. Many preclinical studies have investigated predictive factors for dual PI3K and MEK inhibitor therapy [Sos et al. 2009; Jokinen et al. 2012]. Even though some studies have suggested that responses are commonly seen in some cancer genotypes, no clear predictive markers have been found. Existence of measurable predictive factors would make the design and execution of clinical trials more fruitful.

Dual inhibition: clinical studies

Numerous early-phase clinical studies investigating dual PI3K and MEK targeting are ongoing and some results have been presented in meetings during the past three years. Because of the heterogeneity and early-phase nature of the studies, it is difficult to derive a strong conclusion of the activity in various cancer subgroups and general toxicities. Therefore, we review four different phase I clinical studies and present their results.

Generally, combined PI3K and MEK inhibitor therapy seems to be feasible with manageable safety and toxicity profile. The most common adverse events (AEs) of therapy include diarrhea, rash, fatigue, vomiting and hyperglycemia. Unfortunately, the rate of response seems to be quite low with an overall response rate of 4.7% and a disease control rate of 19.2% when all four presented studies are combined. As in the preclinical models, no clear predictive factors for response have been identified. However, responses have been seen in Ras or Raf mutated cancers, and later studies have enriched these patient populations.

The clinical activity of GDC-0973 (MEK1/2 inhibitor) and GDC-0941 (class I PI3K inhibitor) was studied in 78 patients with advanced solid tumors. The patients received daily both GDC-0973 and GDC-0941 with a 21 day on, 7 days off schedule or with an intermittent schedule where GDC-0973 was dosed on days 1, 4, 8, 11, 15 and 18 with a 28 day cycle and GDC-0941 daily with a 21/7 schedule. DLTs included elevation of grade 3 lipase and grade 4 creatine phosphokinase (CPK). Reported AEs were diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, rash, vomiting, dysgeusia, decreased appetite and CPK elevation. The combination therapy was found to be well tolerated, with toxicities comparable with those reported with single agents in phase I trials. Higher drug doses were tolerated with the intermitted dosing schedule. Partial responses were seen in three patients: one patient with B-Raf mutated melanoma, one with B-Raf mutated pancreatic cancer, and one with K-Ras mutated endometrial cancer. Stable disease lasting over 5 months was observed in five patients [Lorusso et al. 2012].

Daily dosing of BKM120 (pan-PI3K inhibitor) and trametinib (MEK inhibitor) was evaluated with 49 patients with advanced Ras- or B-Raf-mutant cancers. The combination was found to be safe on patients. Grade 3 DLTs included stomatitis, dyspahgia, ejection fraction decrease, CPK elevation, nausea and anorexia. The most commonly observed AEs were listed as dermatitis, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, rash, asthenia, increase in CPK, loss of appetite, pyrexia, stomatitis and hyperglycemia. Partial responses were seen in three patients with K-Ras mutant ovarian cancer and stable disease was observed with two patients with B-Raf mutated melanoma [Bedard et al. 2012].

In another combination study, 49 patients were treated with the pan-PI3K inhibitor copanlisib and the MEK inhibitor refametinib. DLTs included grade 3 aspartate transaminase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevation, hyperglycemia, hypertension, diarrhea, mucositis and rash. The most common AEs included diarrhea, nausea, hyperglycemia, fatigue, rash, anorexia and hypertension. One partial response was seen in a patient with endometrial cancer, and stable disease lasting >4 cycles in 9 patients [Ramanathan et al. 2014].

The combination of BYL719 (PI3Kα inhibitor) and binimetinib (MEK inhibitor) was studied in patients with advanced solid tumors with Ras or B-Raf mutations. A total of 58 patients were treated once a day with BYL719 (80–270 mg) and twice a day with 30 or 45 mg of binimetinib. Common AEs were diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, reduced appetite, rash, pyrexia, fatigue and hyperglycemia. Confirmed partial responses were seen with three of the four patients with K-Ras-mutant ovarian cancer, with one patient with N-Ras mutated melanoma. Stable disease status lasting for over 6 weeks was seen with 18 patients [Juric et al. 2014].

Further directions

A strong rationale and preclinical results have established the groundwork for the clinical development of dual PI3K and MEK inhibitor therapy to solid malignancies. However, early-phase clinical trials presented to date have only shown modest activity of the combination. There is room for new ideas and approaches to improve the antitumor activity and tolerability of the dual PI3K and MEK inhibitor therapy.

Optimal dosing schedule for PI3K and MEK inhibitor combination is unknown. Current clinical dosing regimens of PI3K and MEK inhibitors mainly investigate longer drug exposures with subtotal suppression of their targets. It is likely that more robust target inhibition with higher drug doses would have more antitumor activity. It is possible that higher drug doses with short exposure times could be clinically as tolerable as longer exposure with lower doses, but poses more antitumor activity. Some preclinical studies have shown that short, alternative dosing schedules of PI3K and MEK inhibitor combination can be as effective as longer exposures [Hoeflich et al. 2012; Jokinen et al. 2012]. Furthermore, it is currently unknown if both PI3K and MEK inhibitors need to be administered concurrently for the same period of time, or if either of the drugs could be used intermittently. There is some preclinical evidence for the intermittent uses of the drugs and some clinical studies have also tried to answer this question [Hoeflich et al. 2012; Jokinen et al. 2012; Lorusso et al. 2012]. We believe that studying numerous, highly dual PI3K and MEK therapy-sensitive preclinical models could be a useful way to figure out the optimal dosing schedules from the perspective of cytotoxicity. The dosing regimens could be brought forward for early-phase clinical trials to test their safety and toxicity.

An open question remains if the current PI3K and MEK inhibitors are optimal drugs for cancer therapy. Allosteric MEK inhibitors are well-tolerated agents and do induce robust target inhibition with daily MTD [Adjei et al. 2008; Weekes et al. 2013]. Based on the clinical trials, current PI3K inhibitors are only able to induce modest target inhibition (30–90% inhibition of pAKT and pS6 biomarkers) with daily MTD [Bendell et al. 2011; Moreno Garcia et al. 2011]. Isoform-specific PI3K inhibitors could have less off-tumor effects and, therefore, enable more robust target inhibition with MTD. Promising phase I results of this approach (PI3Kα and MEK inhibitor combination) have recently been presented [Juric et al. 2014]. Furthermore, it is possible that blocking other members of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway could be more effective and tolerable than inhibiting PI3K itself.

Enriching the therapy-sensitive patients in clinical trials is an efficient way to speed up the development of an agent or a combination. Despite the robust preclinical and clinical efforts, no clear predictive factors for dual PI3K and MEK inhibitor therapy have been identified [Sos et al. 2009; Bedard et al. 2012; Jokinen et al. 2012; Lorusso et al. 2012]. From this perspective, it is unlikely that an easily measurable predictive factor to the dual therapy will be identified.

Cytotoxic drug combinations are the backbone of the current cancer therapy. Much less is known about targeted therapy combinations. It is possible that combining either cytotoxics or targeted agents to PI3K and MEK therapy could increase the number of tumors sensitive to them. As an example, novel preclinical works presented recently that antitumor activity of a MEK or mTOR inhibitors can be markedly increased by blocking of BCL-XL anti-apoptotic protein by BH3 mimetic drugs [Corcoran et al. 2012; Faber et al. 2014]. We feel that large-scale preclinical modeling would be appropriate to try to identify the best combinations for ‘dual or triple inhibition’ therapy. However, it remains highly challenging to bring two or three investigational agents concurrently to clinical trials.

Summary

PI3K-AKT-mTOR and Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK are the most commonly altered signaling pathways in solid malignancies, but the clinical efficiency of single-pathway inhibitors have generally been disappointing. Failure of the single-pathway targeting could result from various factors, such as feedback activation of the other pathways or shared downstream targets. Therefore, a strong rationale for dual PI3K and MEK inhibitor therapy for cancer treatment exists. Various preclinical models have identified this therapy to be efficient in various cancers and genotypes. Currently, numerous early-phase clinical trials investigating dual PI3K and MEK therapy are ongoing. Clinical results presented to date have shown that dual targeting is feasible with manageable toxicity and safety profile, but the rate of response is quite low. It is possible that efficiency of dual targeting could be increased by alternative dosing schedules, newer generations of agents, intelligent drug combinations, or enriching the patients with predictive factors.

Footnotes

Funding: The study was supported by Cancer Society of Northern Finland, Emil Aaltonen Foundation, Finnish Foundation for Tuberculosis Resistance, Finnish Oncological Society, Oulu University Hospital, Orion-Farmos Science Foundation, Sigrid Juselius Foundation and Thelma Mäkikyrö foundation.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing this article.

Contributor Information

E. Jokinen, Department of Oncology and Radiotherapy, Oulu University Hospital, Oulu, Finland, PB20, 90029 OYS

J.P. Koivunen, Department of Oncology and Radiotherapy, Oulu University Hospital, Oulu, Finland

References

- Adjei A., Cohen R., Franklin W., Morris C., Wilson D., Molina J., et al. (2008) Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the oral, small-molecule mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) in patients with advanced cancers. J Clin Oncol 26: 2139–2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almoguera C., Shibata D., Forrester K., Martin J., Arnheim N., Perucho M. (1988) Most human carcinomas of the exocrine pancreas contain mutant C-K-Ras genes. Cell 53: 549–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barretina J., Taylor B., Banerji S., Ramos A., Lagos-Quintana M., Decarolis P., et al. (2010) Subtype-specific genomic alterations define new targets for soft-tissue sarcoma therapy. Nat Genet 42: 715–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baselga J., Campone M., Piccart M., Burris H., 3rd, Rugo H., Sahmoud T., et al. (2012) Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 366: 520–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard P., Tabernero J., Kurzrock R., Britten C., Stathis A., Perez-Garcia J., et al. (2012) A phase Ib, open-label, multicenter, dose-escalation study of the oral PAN-PI3K inhibitor BKM120 in combination with the oral MEK1/2 inhibitor GSK1120212 in patients (pts) with selected advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 30(Suppl.): abstract 3003. [Google Scholar]

- Bellmunt J., Teh B., Tortora G., Rosenberg J. (2013) Molecular targets on the horizon for kidney and urothelial cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 10: 557–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendell J., Rodon J., Burris H., De Jonge M., Verweij J., Birle D., et al. (2011) Phase I, dose-escalation study of BKM120, an oral pan-class I PI3K inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 30: 282–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennouna J., Lang I., Valladares-Ayerbes M., Boer K., Adenis A., Escudero P., et al. (2011) A phase II, open-label, randomised study to assess the efficacy and safety of the MEK1/2 Inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) versus capecitabine monotherapy in patients with colorectal cancer who have failed one or two prior chemotherapeutic regimens. Invest New Drugs 29: 1021–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bismar T., Yoshimoto M., Vollmer R., Duan Q., Firszt M., Corcos J., et al. (2011) PTEN genomic deletion is an early event associated with ERG gene rearrangements in prostate cancer. BJU Int 107: 477–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollag G., Hirth P., Tsai J., Zhang J., Ibrahim P., Cho H., et al. (2010) Clinical efficacy of a RAF inhibitor needs broad target blockade in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nature 467: 596–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann S., Hofmann I., Schnell C., Fritsch C., Wee S., Lane H., et al. (2009) Specific apoptosis induction by the dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 in HER2 amplified and PIK3CA mutant breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 22299–22304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brana I., Siu L. (2012) Clinical development of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors for cancer treatment. BMC Med 10: 161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan M., Rampal R., Harding J., Klimek V., Chung Y., Merghoub T., et al. (2012) Progression of RAS-mutant leukemia during raf inhibitor treatment. N Engl J Med 367: 2316–2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2008) Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature 455: 1061–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2011) Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 474: 609–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2012a) Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature 489: 519–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network (2012b) Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 487: 330–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network (2012c) Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 490: 61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2013) Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 497: 67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2014a) Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature 513: 202–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2014b) Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature 507: 315–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2014c) Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 511: 543–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandarlapaty S., Sawai A., Scaltriti M., Rodrik-Outmezguine V., Grbovic-Huezo O., Serra V., et al. (2010) AKT inhibition relieves feedback suppression of receptor tyrosine kinase expression and activity. Cancer Cell 19: 58–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman P., Hauschild A., Robert C., Haanen J., Ascierto P., Larkin J., et al. (2011) Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med 364: 2507–2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran R., Cheng K., Hata A., Faber A., Ebi H., Coffee E., et al. (2012) Synthetic lethal interaction of combined BCL-XL and MEK inhibition promotes tumor regressions in KRAS mutant cancer models. Cancer Cell 23: 121–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies H., Bignell G., Cox C., Stephens P., Edkins S., Clegg S., et al. (2002) Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 417: 949–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M., Fox P., Papadopoulos N., Bedikian A., Hwu W., Lazar A., et al. (2012) Phase I study of the combination of sorafenib and temsirolimus in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 18: 1120–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienstmann R., Rodon J., Markman B., Tabernero J. (2011) Recent developments in anti-cancer agents targeting PI3K, AKT and mTORC1/2. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov 6: 210–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen T., Ahmad T., Flaherty K., Gore M., Kaye S., Marais R., et al. (2006) Sorafenib in advanced melanoma: a phase II randomised discontinuation trial analysis. Br J Cancer 95: 58–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman J., Chen L., Tan X., Crosby K., Guimaraes A., Upadhyay R., et al. (2008) Effective use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors to treat mutant KRAS G12D and PIK3CA H1047R murine lung cancers. Nat Med 14: 1351–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman J., Luo J., Cantley L. (2006) The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat Rev Genet 7: 606–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escudier B., Eisen T., Stadler W., Szczylik C., Oudard S., Siebels M., et al. (2007) Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 356: 125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber A., Coffee E., Costa C., Dastur A., Ebi H., Hata A., et al. (2014) mTOR inhibition specifically sensitizes colorectal cancers with KRAS or BRAF mutations to BCL-2/BCL-Xl inhibition by suppressing MCL-1. Cancer Discov 4: 42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber A., Li D., Song Y., Liang M., Yeap B., Bronson R., et al. (2009) Differential Induction of apoptosis in HER2 and EGFR addicted cancers following PI3K inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 19503–19508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty K., Infante J., Daud A., Gonzalez R., Kefford R., Sosman J., et al. (2012) Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med 367: 1694–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollob J., Wilhelm S., Carter C., Kelley S. (2006) Role of RAF kinase in cancer: therapeutic potential of targeting the RAF/MEK/ERK signal transduction pathway. Semin Oncol 33: 392–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D., Weinberg R. (2011) Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144: 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauschild A., Grob J., Demidov L., Jouary T., Gutzmer R., Millward M., et al. (2012) Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 380: 358–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho A., Grewal R., Leboeuf R., Sherman E., Pfister D., Deandreis D., et al. (2013) Selumetinib-enhanced radioiodine uptake in advanced thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med 368: 623–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeflich K., Merchant M., Orr C., Chan J., Den Otter D., Berry L., et al. (2012) Intermittent administration of MEK inhibitor GDC-0973 plus PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941 Triggers robust apoptosis and tumor growth inhibition. Cancer Res 72: 210–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeflich K., O’Brien C., Boyd Z., Cavet G., Guerrero S., Jung K., et al. (2009) In vivo antitumor activity of MEK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors in basal-like breast cancer models. Clin Cancer Res 15: 4649–4664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudes G., Carducci M., Tomczak P., Dutcher J., Figlin R., Kapoor A., et al. (2007) Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 356: 2271–2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infante J., Fecher L., Falchook G., Nallapareddy S., Gordon M., Becerra C., et al. (2012) Safety, pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and efficacy data for the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol 13: 773–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokinen E., Laurila N., Koivunen J. (2012) Alternative dosing of dual PI3K and MEK inhibition in cancer therapy. BMC Cancer 12: 612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juric D., Soria J., Sharma S., Banerjee U., Azaro A., Desai J., et al. (2014) A phase 1b Dose-escalation study of BYL719 plus binimetinib (MEK162) in patients with selected advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 32:5s (Suppl.): abstract 9051. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura E., Nikiforova M., Zhu Z., Knauf J., Nikiforov Y., Fagin J. (2003) High prevalence of BRAF mutations in thyroid cancer: genetic evidence for constitutive activation of the RET/PTC-RAS-BRAF signaling pathway in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Res 63: 1454–1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S., Liu C., Ko S., Chang H., Liu T., Chang K. (2005) Copy number amplification of 3Q26-27 oncogenes in microdissected oral squamous cell carcinoma and oral brushed samples from areca chewers. J Pathol 206: 417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llovet J., Ricci S., Mazzaferro V., Hilgard P., Gane E., Blanc J., et al. (2008) Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 359: 37–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorusso P., Shapiro G., Panday S., Kwak E., Jones C., Belvin M., et al. (2012) A first-in-human phase Ib study to evaluate the MEK inhibitor GDC-0973, combined with the pan-PI3K Inhibitor GDC-0941, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 30(Suppl.): abstract 2566. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza M., Er E., Blenis J. (2011) The RAS-Erk and PI3K-mTOR pathways: cross-talk and compensation. Trends Biochem Sci 36: 320–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Garcia V., Baird R., Shah K., Basu B., Tunariu N., Blanco M., et al. (2011) A phase I study evaluating GDC-0941, an oral phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K) inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors or multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol 29(Suppl.): abstract 3021. [Google Scholar]

- Motzer R., Escudier B., Oudard S., Hutson T., Porta C., Bracarda S., et al. (2008) Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet 372: 449–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly K., Rojo F., She Q., Solit D., Mills G., Smith D., et al. (2006) mTOR inhibition induces upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and activates AKT. Cancer Res 66: 1500–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulikakos P., Zhang C., Bollag G., Shokat K., Rosen N. (2010) RAF inhibitors transactivate RAF dimers and ERK signalling in cells with wild-type BRAF. Nature 464: 427–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan R., Von Hoff D., Eskens F., Blumenschein G., Richards D., Renshaw F., et al. (2014) A Phase 1b trial of PI3K inhibitor copanlisib (BAY 80-6946) combined with the allosteric-MEK Inhibitor refametinib (BAY 86-9766) in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 32:5s(Suppl.): abstract 2588. [Google Scholar]

- Rinehart J., Adjei A., Lorusso P., Waterhouse D., Hecht J., Natale R., et al. (2004) Multicenter phase II study of the oral MEK inhibitor, CI-1040, in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung, breast, colon, and pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 22: 4456–4462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra V., Scaltriti M., Prudkin L., Eichhorn P., Ibrahim Y., Chandarlapaty S., et al. (2011) PI3K inhibition results in enhanced HER Signaling and acquired ERK dependency in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer. Oncogene 30: 2547–2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solit D., Garraway L., Pratilas C., Sawai A., Getz G., Basso A., et al. (2006) BRAF mutation predicts sensitivity to MEK inhibition. Nature 439: 358–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sos M., Fischer S., Ullrich R., Peifer M., Heuckmann J., Koker M., et al. (2009) Identifying genotype-dependent efficacy of single and combined PI3K- and MAPK-pathway inhibition in cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 18351–18356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa S., Fernandes P., Ramos M. (2008) Farnesyltransferase inhibitors: a detailed chemical view on an elusive biological problem. Curr Med Chem 15: 1478–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su F., Viros A., Milagre C., Trunzer K., Bollag G., Spleiss O., et al. (2012) RAS mutations in cutaneous squamous-cell carcinomas in patients treated with BRAF inhibitors. N Engl J Med 366: 207–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turke A., Song Y., Costa C., Cook R., Arteaga C., Asara J., et al. (2012) MEK inhibition leads to PI3K/AKT activation by relieving a negative feedback on ERBB receptors. Cancer Res 72: 3228–3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan K., Barbie D., Davies M., Rabinovsky R., McNear C., Kim J., et al. (2009) AKT-independent signaling downstream of oncogenic PIK3CA mutations in human cancer. Cancer Cell 16: 21–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace E., Lyssikatos J., Yeh T., Winkler J., Koch K. (2005) Progress towards therapeutic small molecule MEK inhibitors for use in cancer therapy. Curr Top Med Chem 5: 215–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wander S., Hennessy B., Slingerland J. (2011) Next-generation mTOR inhibitors in clinical oncology: how pathway complexity informs therapeutic strategy. J Clin Invest 121: 1231–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weekes C., Von Hoff D., Adjei A., Leffingwell D., Eckhardt S., Gore L., et al. (2013) Multicenter phase I trial of the mitogen-activated protein kinase 1/2 inhibitor BAY 86-9766 in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res 19: 1232–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigelt B., Warne P., Downward J. (2011) PIK3CA mutation, but not PTEN loss of function, determines the sensitivity of breast cancer cells to mTOR inhibitory drugs. Oncogene 30: 3222–3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S., Adnane L., Newell P., Villanueva A., Llovet J., Lynch M. (2008) Preclinical overview of sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor that targets both RAF and VEGF and PDGF Receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Mol Cancer Ther 7: 3129–3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y., Serra V., Prudkin L., Scaltriti M., Murli S., Rodriguez O., et al. (2013) Evaluation and clinical analyses of downstream targets of the AKT inhibitor GDC-0068. Clin Cancer Res 19: 6976–6986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J., Shah M., Ito T., Bohas C., Wolin E., Van Cutsem E., et al. (2011) Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med 364: 514–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer L., Barlesi F., Martinez-Garcia M., Dieras V., Schellens J., Spano J., et al. (2014) Phase I expansion and pharmacodynamic study of the oral MEK inhibitor RO4987655 (CH4987655) in selected patients with advanced cancer with RAS-RAF mutations. Clin Cancer Res 20: 4251–4261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]