Abstract

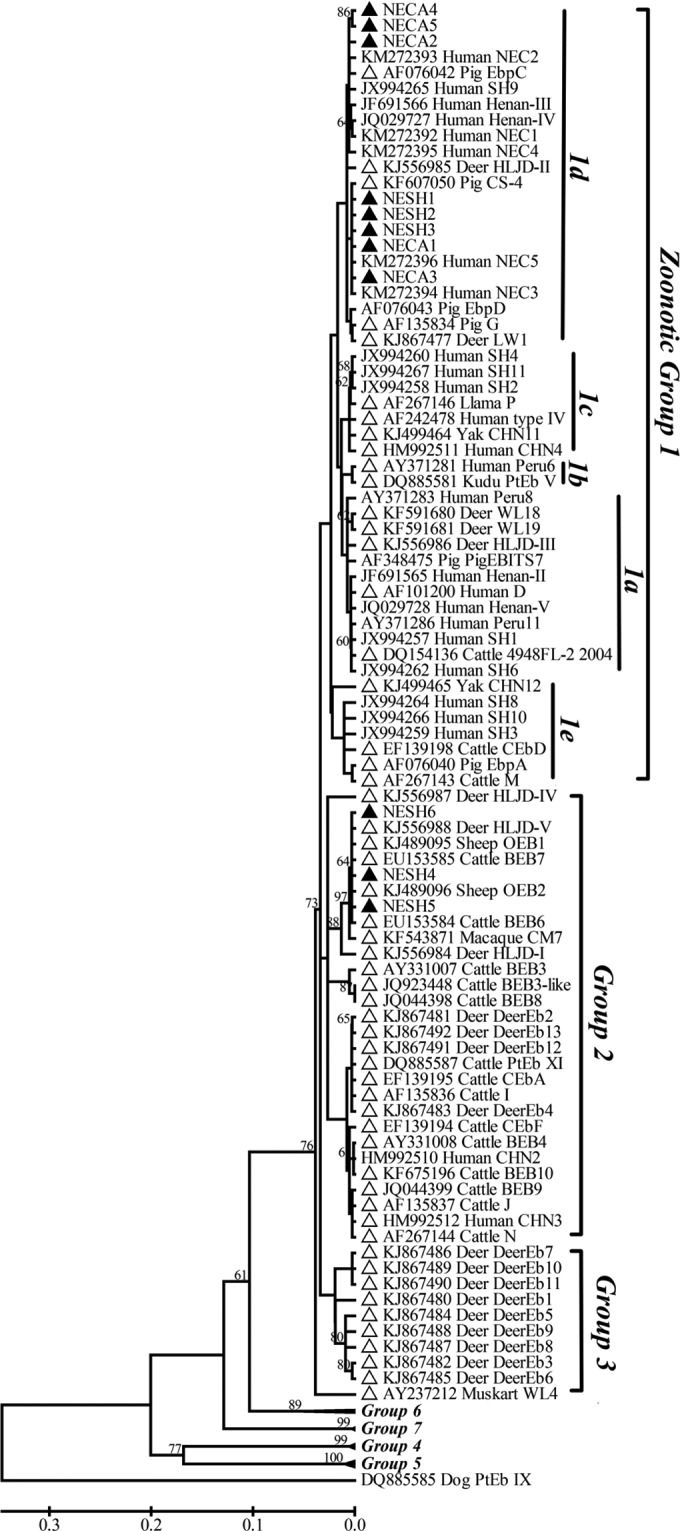

This study investigated fecal specimens from 489 sheep and 537 cattle in multiple cities in northeast China for the prevalence and genetic characteristics of Enterocytozoon bieneusi by PCR and sequencing of the ribosomal internal transcribed spacer. Sixty-eight sheep specimens (13.9%) and 32 cattle specimens (6.0%) were positive for E. bieneusi. Sequence polymorphisms enabled the identification of 9 known genotypes (BEB4, BEB6, CM7, CS-4, EbpC, G, I, J, and OEB1) and 11 new genotypes (NESH1 to NESH6 and NECA1 to NECA5). The genotypes formed two genetic clusters in a phylogenetic analysis, with CS-4, EbpC, G, NESH1 to NESH3, and NECA1 to NECA5 distributed in zoonotic group 1 and BEB4, BEB6, CM7, EbpI, J, OEB1, and NESH4 to NESH6 distributed in potentially host-adapted group 2. Nearly 70% of cases of E. bieneusi infections in sheep were contributed by human-pathogenic genotypes BEB6, CS-4, and EbpC, and over 80% of those in cattle were by genotypes BEB4, CS-4, EbpC, I, and J. The cooccurrence of genotypes BEB4, CS-4, EbpC, I, and J in domestic ruminants and children in northeast China and the identification of BEB6 and EbpC in humans and water in central China imply the possibility of zoonotic transmission. This study also summarizes E. bieneusi genotypes obtained from ruminants worldwide and displays their host ranges, geographical distributions, and phylogenetic relationships. The data suggest a host range expansion in some group 2 genotypes (notably BEB4, BEB6, I, and J) that were previously considered to be adapted to ruminants. We should be concerned about the increasing zoonotic importance of group 2 genotypes with low host specificity.

INTRODUCTION

Microsporidia are a large and diverse group of obligately intracellular parasites that have been implicated as both human and animal pathogens (1). These parasitic protists are genetically related to fungi and feature environmentally resistant spore forms (1). Microsporidia differentiate from meronts into spores that are then defecated by the host into the environment and start a new round of eukaryotic cell invasion by using a highly specialized organelle, the polar tube, followed by intracellular replication (2). Of approximately 1,300 microsporidian species in 160 genera reported thus far, 14 species in 8 genera have been documented in human infections (3). Enterocytozoon bieneusi has emerged as an opportunistic pathogen leading to infectious diarrhea in humans; it has been associated with immune suppression and is responsible for almost 90% of reported cases of human microsporidiosis (4). It also affects immunocompetent individuals and a variety of domestic and wild animals, and even birds (4). Contact with infected humans and animals or contaminated food and water may contribute to the acquisition of E. bieneusi infections (1, 5–7).

At present, genotyping of E. bieneusi on the basis of the ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) has characterized over 200 distinct genotypes (5). The genotype nomenclature used here is according to the established naming system (8). Coupled with phylogeny, these genotypes form several genetically isolated clusters, among which a large cluster (group 1) includes zoonotic genotypes, some of which have been found in both humans and animals and have established zoonotic potential (9). The remaining ones are clustered into several potentially host-adapted groups and previously were considered to be specific to animals (9). Nevertheless, with improvements of genotypic identification of E. bieneusi from various host species and geographic regions, some of the genotypes in host-adapted group 2 were recognized to have expanded their host range and even to have infected humans, and they should also be considered to have zoonotic importance (10, 11).

E. bieneusi has repeatedly been reported to infect humans, nonhuman primates, cats, cattle, dogs, horses, pigs, birds, and a range of wild mammals (4). Both zoonotic and potentially host-adapted genotypes can be the causative agents of E. bieneusi infections in many human and animal species, and animals are potential reservoirs for genotypes leading to human infections (4, 9). The genotypes of E. bieneusi in specific hosts usually vary (9). Humans and pigs are predominantly infected with group 1 genotypes (D, EbpC, IV, etc.), and potential zoonotic transmission of microsporidiosis between humans and pigs has been proposed (4–6, 12–14). Regarding ruminants, cattle, deer, and goats are colonized dominantly with group 2 genotypes and sporadically with group 1 genotypes, but this was believed to have limited public health significance (11, 15–36). Yet some group 2 genotypes that were previously considered to be ruminant specific, such as BEB6, have been shown to have less host specificity and are becoming of increasing zoonotic concern (10). To date, very limited genetic data have been generated for sheep-harbored E. bieneusi. Two recent studies described the occurrence of group 2 genotypes BEB6, OEB1, and OEB2 in lambs (10, 14). However, it is still unknown if sheep can carry group 1 genotypes.

In China, domestic ruminants are commonly in close contact with humans, and the environmental shedding of E. bieneusi spores may be a threat to public health. This study was carried out to explore the prevalence and genetic characteristics of E. bieneusi in 489 sheep and 537 cattle of different age categories from suburban areas of the cities of Harbin, Daqing, Qiqihar, and Songyuan, northeast China, and to evaluate the potential role of sheep and cattle in transmission of human microsporidiosis. This study also summarizes E. bieneusi genotypes identified from ruminants worldwide, displaying their host ranges, geographical distributions, and phylogenetic relationships, and attempts to explore the increased public health concerns of ruminant-harbored genotypes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

This study was performed in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Ministry of Health, China (37). Prior to experiments, the protocol of the current study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Northeast Agricultural University (approved protocol number SRM-08). For specimen collection, we obtained permission from animal owners. No specific permits were required for the described field studies, and the locations where we sampled are not privately owned or protected in any way. The field studies did not involve endangered or protected species.

Specimen collection.

Fecal specimen collection was done from household sheep in suburban Harbin (n = 164) in September 2013 and from intensively bred sheep on a farm in suburban Daqing (n = 154) in July 2014 and on a farm in suburban Qiqihar (n = 171) in July 2014. The ages of the animals in Harbin are unknown. Sheep younger than 1 year old were sampled from Daqing. Stools were obtained from lambs (<1 year; n = 148) and adult sheep (>1 year; n = 23) in Qiqihar. Fecal specimens from intensively bred dairy cattle (n = 526) were collected on three farms, in suburban areas of Harbin (n = 196) in October 2013, Daqing (n = 140) in July 2014, and Qiqihar (n = 190) in April 2014, and samples from household dairy cattle (n = 11) in Songyuan were collected in October 2014. Sixty-nine and 127 specimens were from preweaned (<2 months) and weaned (>2 months) cattle, respectively, in Harbin. Cattle sampled in Daqing and Songyuan were older than 2 months of age, and those in Qiqihar were younger than 2 months of age. Each specimen (about 30 g) was collected immediately after being defecated on the ground of the pen, using a sterile disposable latex glove. Specimens from Harbin were placed individually in 50-ml plastic containers and stored in 2.5% (wt/vol) potassium dichromate at 4°C, while specimens from Daqing, Qiqihar, and Songyuan were packaged individually in disposable plastic bags and stored directly at −20°C for DNA extraction. One specimen per animal was used, and the animals were all healthy at the time of sampling. Harbin, Daqing, Qiqihar, and Songyuan are neighboring cities located in the southwestern end of Heilongjiang Province, northeast China.

DNA extraction, PCR, and statistical analysis.

Feces stored in potassium dichromate were washed twice with distilled water by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature prior to DNA extraction. Genomic DNAs were extracted from approximately 0.3-g washed specimens from Harbin and frozen specimens from Daqing, Qiqihar, and Songyuan, using Stool DNA rapid extraction kits (Spin-Column; Tiangen, China) according to the manufacturer-recommended procedures. PCRs were performed using a set of nested primers specific to E. bieneusi that amplified the entire ITS region and portions of the flanking large- and small-subunit rRNAs (392 bp), as previously described (38). PCR products were visualized by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide. Infection rates between age groups and between animal groups from various locations were compared by use of the chi-square test, with significance indicated by P values of <0.05, as implemented in SPSS software, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Genotyping and phylogeny.

The secondary PCR products of expected size were sequenced in both directions at the Beijing Genomics Institute, China. After being edited using Chromas Pro 1.33 (Technelysium Pty. Ltd., Helensvale, Queensland, Australia), the nucleotide sequences were aligned with the reference sequences already deposited in GenBank by use of the program ClustalX 1.81 (ftp://ftp-igbmc.u-strasbg.fr/pub/ClustalX/) to determine E. bieneusi genotypes. Mixed E. bieneusi infections were determined by the appearance of double, overlapping peaks at the ITS region on the sequencing chromatogram and by subsequent TA cloning. A neighbor-joining tree was constructed to better present the diversity of genotypes and the genetic relationships of newly obtained isolates to known ones, using the software Mega 4 (http://www.megasoftware.net/), based on evolutionary distances calculated by the Kimura two-parameter model. The ITS tree was rooted with an outlier sequence under GenBank accession no. DQ885585. Bootstrap analysis was used to evaluate the reliability of clusters by using 1,000 replicates.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Unique nucleotide sequences of the new genotypes NESH1 to NESH6 and NECA1 to NECA5 obtained in this study were deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers KP732475 to KP732485.

RESULTS

Infection rates of E. bieneusi in sheep and cattle.

Nested PCR analysis of the ITS region detected E. bieneusi in 68 of 489 (13.9%) sheep fecal specimens, giving infection rates of 6.7% (11/164 specimens) in Harbin, 20.1% (31/154 specimens) in Daqing, and 15.2% (26/171 specimens) in Qiqihar (Table 1). Lambs (24/148 specimens [16.2%]) had an infection rate that was slightly higher than that of adult sheep (2/23 specimens [8.7%]) in Qiqihar (P > 0.05; χ2 = 0.4). The difference in infection rates between intensively bred animals in Daqing and household animals in Harbin was significant (P < 0.01; χ2 = 12.5). A significant difference in infection rates was also observed between animal groups from Qiqihar and Harbin (P < 0.05; χ2 = 6.2).

TABLE 1.

Prevalences and genotype distributions of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in sheep and cattle of different age categories from various cities, northeast China

| Animal host | City | Host age | Prevalence (% [no. of positive animals/total no. of animals tested]) | Genotype(s) (no. of specimens) | Group 1 genotype(s)b (no. of specimens) | Human-pathogenic genotype(s)c (no. of specimens) | % human-pathogenic genotypes (no. of positive specimens/total no. of specimens) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheep | Harbin | 6.7 (11/164) | BEB6 (3), CS-4 (4), NESH1 (1), NESH2 (1), NESH3 (1), CS-4/EbpCa (1) | CS-4 (4), NESH1 (1), NESH2 (1), NESH3 (1), CS-4/EbpCa (1) | BEB6 (3), CS-4 (4), CS-4/EbpCa (1) | 75.0 (9/12) | |

| Daqing | <1 yr | 20.1 (31/154) | BEB6 (10), CM7 (2), BEB6/CM7a (3), BEB6/NESH4a (3), BEB6/OEB1a (5) | BEB6 (21) | 61.8 (21/34) | ||

| Qiqihar | <1 yr | 16.2 (24/148) | BEB6 (14), CM7 (1), NESH5 (1), OEB1 (2), BEB6/CM7a (2), BEB6/NESH6a (1) | BEB6 (17) | 70.8 (17/24) | ||

| Qiqihar | >1 yr | 8.7 (2/23) | BEB6 (1), OEB1 (1) | BEB6 (1) | 50.0 (1/2) | ||

| Total | 13.9 (68/489) | BEB6 (28), CM7 (3), CS-4 (4), NESH1 to NESH3 (1 each), NESH5 (1), OEB1(3), BEB6/CM7a (5), BEB6/NESH4a (3), BEB6/NESH6a (1), BEB6/OEB1a (5), CS-4/EbpCa (1) | CS-4 (4), NESH1 to NESH3 (1 each), CS-4/EbpCa (1) | BEB6 (42), CS-4 (4), CS-4/EbpCa (1) | 66.7 (48/72) | ||

| Cattle | Harbin | <2 mo | 5.8 (4/69) | BEB4 (1), J (1), CS-4/EbpCa (1), CS-4/NECA1a (1) | CS-4/EbpCa (1), CS-4/NECA1a (1) | BEB4 (1), CS-4 (1), J (1), CS-4/EbpCa (1) | 83.3 (5/6) |

| Harbin | >2 mo | 7.1 (9/127) | CS-4 (3), EbpC (1), J (1), BEB4/Ja (1), CS-4/NECA3a (1), EbpC/NECA2a (1) | CS-4 (3), EbpC (1), CS-4/NECA3a (1), EbpC/NECA2a (1) | CS-4 (4), EbpC (2), J (1), BEB4/Ja (1) | 81.8 (9/11) | |

| Daqing | >2 mo | 1.4 (2/140) | |||||

| Qiqihar | <2 mo | 8.4 (16/190) | G (1), J (4), I/Ja (3), NECA4/NECA5a (1) | G (1), NECA4/NECA5a (1) | J (4), I/Ja (3) | 76.9 (10/13) | |

| Songyuan | >2 mo | 9.1 (1/11) | J (1) | J (1) | 100 (1/1) | ||

| Total | 6.0 (32/537) | BEB4 (1), CS-4 (3), EbpC (1), G (1), J (7), BEB4/Ja (1), CS-4/EbpCa (1), CS-4/NECA1a (1), CS-4/NECA3a (1), EbpC/NECA2a (1), I/Ja (3), NECA4/NECA5a (1) | CS-4 (3), EbpC (1), G (1), CS-4/EbpCa (1), CS-4/NECA1a (1), CS-4/NECA3a (1), EbpC/NECA2a (1), NECA4/NECA5a (1) | BEB4 (1), CS-4 (5), EbpC (2), J (7), BEB4/Ja (1), CS-4/EbpCa (1), I/Ja (3) | 80.6 (25/31) |

Thirty-two of 537 (6.0%) dairy cattle surveyed were infected with E. bieneusi, with rates of 6.6% (13/196 specimens) in Harbin, 1.4% (2/140 specimens) in Daqing, 8.4% (16/190 specimens) in Qiqihar, and 9.1% (1/11 specimens) in Songyuan (Table 1). Infection rates of E. bieneusi in cattle of various ages are shown in Table 1. A slight difference in total infection rates was observed between preweaned (20/259 specimens [7.7%]) and weaned (12/278 specimens [4.3%]) cattle (P > 0.05; χ2 = 2.8).

Genotype distribution.

Nucleotide DNA sequences were obtained for 57 of 68 pathogen-positive sheep specimens and 22 of 32 pathogen-positive cattle specimens (Table 1). Sequence alignment and analysis revealed the presence of 11 distinct E. bieneusi genotypes in sheep (5 known [BEB6, CM7, CS-4, EbpC, and OEB1] and 6 novel [NESH1 to NESH6]) and 11 different genotypes in cattle (6 known [BEB4, CS-4, EbpC, G, I, and J] and 5 novel [NECA1 to NECA5]) (Table 1), among which genotypes BEB4, BEB6, CS-4, EbpC, I, and J have been reported for human infections (Table 2). The differences in DNA sequences between any two of genotypes CS-4, EbpC, G, NESH1 to NESH3, and NECA1 to NECA5 and between any two of genotypes BEB4, BEB6, CM7, I, J, OEB1, and NESH4 to NESH6 were smaller than three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (data not shown). Nevertheless, the DNA sequences of genotypes CS-4, EbpC, G, NESH1 to NESH3, and NECA1 to NECA5 differed from those of the remaining ones by over 20 SNPs (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Geographical distributions and host ranges of Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes identified from sheep and cattle in northeast China

| Genotype | Citya (no. of positive specimens) | Host/sourceb (locationc) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BEB4 | Harbin (2) | Humans (China and CZE), cattle (Argentina, China, South Africa, and USA), yaks (China), and pigs (China) | 4, 11, 16–18, 27, 44, 48 |

| BEB6 | Daqing (21), Harbin (3), Qiqihar (18) | Humans (China), NHP (China), cattle (USA), sheep (China and Sweden), goats (Peru), deer (China), cats (China), and WW (China and Tunisia) | 4, 10, 12, 14–16, 40–43 |

| CM7 | Daqing (5), Qiqihar (3) | NHP (China) | 42 |

| CS-4 | Harbin (11) | Humans (China), NHP (China), and pigs (China) | 5, 14, 38, 42 |

| EbpC | Harbin (4) | Humans (China, Peru, Thailand, and Vietnam), NHP (China), cattle (Argentina), pigs (China, Germany, Japan, Switzerland, and Thailand), dogs (China), beavers (USA), foxes (USA), muskrats (USA), otters (USA), raccoons (USA), wild boar (Austria, Czech Republic, Poland, and Slovak Republic), DSW (China), lake water (China), and WW (China) | 5, 6, 12–14, 16, 17, 38–42, 50, 51 |

| G | Qiqihar (1) | Pigs (China and Germany), horses (CZE), wild boar (CZE), and DSW (China) | 4, 14, 49, 50 |

| I | Qiqihar (3) | Humans (China), NHP (China), cattle (Argentina, China, CZE, Germany, South Korea, South Africa, and USA), deer (USA), yaks (China), pigs (Spain), and cats (China) | 4, 11, 16–18, 27, 31, 35, 41, 42, 45, 48 |

| J | Harbin (3), Qiqihar (7), Songyuan (1) | Humans (China), cattle (China, Germany, South Korea, Portugal, and USA), yaks (China), deer (USA), chickens (Germany), and birds (Iran) | 4, 11, 16–18, 35, 47, 48 |

| OEB1 | Daqing (5), Qiqihar (3) | Sheep (Sweden) | 10 |

| NESH1 | Harbin (1) | Sheep | This study |

| NESH2 | Harbin (1) | Sheep | This study |

| NESH3 | Harbin (1) | Sheep | This study |

| NESH4 | Daqing (3) | Sheep | This study |

| NESH5 | Qiqihar (1) | Sheep | This study |

| NESH6 | Qiqihar (1) | Sheep | This study |

| NECA1 | Harbin (1) | Cattle | This study |

| NECA2 | Harbin (1) | Cattle | This study |

| NECA3 | Harbin (1) | Cattle | This study |

| NECA4 | Qiqihar (1) | Cattle | This study |

| NECA5 | Qiqihar (1) | Cattle | This study |

City where E. bieneusi was detected in this study.

NHP, nonhuman primates; WW, wastewater; DSW, drinking source water.

Location where E. bieneusi was detected before this work; CZE, Czech Republic.

Household sheep in Harbin were dominantly affected by genotypes CS-4 (4/11 specimens) and BEB6 (3/11 specimens), followed by NESH1 to NESH3 (1 each) and a mixed CS-4/EbpC genotype (1/11 specimens) (Table 1). In Daqing, 21 E. bieneusi-positive specimens analyzed contained the BEB6 genotype sequence, with 10 single infections and 11 mixed infections of the BEB6/CM7 (n = 3), BEB6/NESH4 (n = 3), or BEB6/OEB1 (n = 5) genotype, and 2 specimens contained the CM7 genotype sequence (Table 1). Single-genotype infections (BEB6, n = 15; CM7, n = 1; NESH5, n = 1; and OEB1, n = 3) were seen in 20 farm animals from Qiqihar, and mixed-genotype infections (BEB6/CM7, n = 2; and BEB6/NESH6, n = 1) were seen in 3 animals (Table 1). Taken together, the data showed that E. bieneusi infections in sheep from Heilongjiang were contributed by genotypes BEB6 (n = 28), CM7 (n = 3), CS-4 (n = 4), NESH1 to NESH3 (n = 1 each), NESH5 (n = 1), and OEB1 (n = 3) and by the mixed genotypes BEB6/CM7 (n = 5), BEB6/NESH4 (n = 3), BEB6/NESH6 (n = 1), BEB6/OEB1 (n = 5), and CS-4/EbpC (n = 1) (Table 1).

Genotypes CS-4 (3/12 specimens), J (2/12 specimens), BEB4 (1/12 specimens), EbpC (1/12 specimens), and BEB4/J (1/12 specimens) and mixed genotypes CS-4/EbpC (1/12 specimens), CS-4/NECA1 (1/12 specimens), CS-4/NECA3 (1/12 specimens), and EbpC/NECA2 (1/12 specimens) were the contributors to E. bieneusi infections in Harbin cattle, J (4/9 specimens), G (1/9 specimens), and mixed I/J (3/9 specimens) and NECA4/NECA5 (1/9 specimens) in Qiqihar cattle, and J (1/1 specimen) in Songyuan cattle (Table 1). In total, genotype J (7/22 specimens) was the most prevalent E. bieneusi genotype in cattle, followed by CS-4 (3/22 specimens), BEB4, EbpC, and G (1/22 specimens [each]), mixed I/J (3/22 specimens), and mixed BEB4/J, CS-4/EbpC, CS-4/NECA1, CS-4/NECA3, EbpC/NECA2, and NECA4/NECA5 (1/22 specimens [each]) (Table 1).

Phylogenetic relationships.

The genetic relationships of the ITS nucleotide sequences of the new genotypes determined in this study and of known genotypes were assessed as illustrated in Fig. 1. The 20 E. bieneusi genotypes identified herein formed two genetic clusters, with CS-4, EbpC, G, NESH1 to NESH3, and NECA1 to NECA5 distributed in zoonotic group 1 and BEB4, BEB6, CM7, I, J, OEB1, and NESH4 to NESH6 distributed in potentially host-adapted group 2. Group 1 also included genotypes detected in HIV-positive and -negative individuals from Henan Province, central China (D, EbpC, EbpD, IV, Peru8, Peru11, PigEBITS7, and Henan-I to Henan-V) (6), and in children from Shanghai, central China, and the cities of Changchun, Harbin, and Daqing, northeast China (CHN4, CS-4, D, EbpA, EbpC, Henan-I, Henan-IV, IV, NEC1 to NEC5, Peru11, SH1 to SH4, SH6, and SH8 to SH11) (5, 11, 12). In addition, genotypes 4948 FL-2 2004, CEbD, CHN11, CHN12, HLJD-II, HLJD-III, LW1, M, P, Peru6, PtEb V, WL18, and WL19, reported for ruminants in previous studies, were also seen in group 1. Group 2 contained genotypes OEB1 and OEB2, originally identified in sheep from Sweden (10); I, J, and N, identified in cattle from Germany (20, 21); BEB3, BEB4, and BEB6 to BEB9, identified in cattle from the United States (16, 29, 32); BEB10, identified in cattle from Argentina (17); BEB3-like, identified in cattle from South Africa; CEbA and CEbF, identified in cattle from South Korea (22); PtEb XI, identified in cattle from Portugal (25); CHN2 and CHN3, identified in humans from China (11); DeerEb2, DeerEb12, and DeerEb13, identified in deer from the United States (35); CM7, identified in monkeys from China; and HLJD-I, HLJD-IV, and HLJD-V, identified in deer from China (15).

FIG 1.

Phylogenetic relationships among Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes identified in this study and others already deposited in GenBank, as inferred by a neighbor-joining analysis of the ITS rRNA gene, based on genetic distances calculated by the Kimura two-parameter model. Bootstrap values of >60% for 1,000 replicates are shown on nodes. The known genotypes identified in ruminants around the world and the new genotypes found in sheep and cattle in this study are indicated by open and filled triangles, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Heilongjiang is a poor agricultural province in China, with an extensive livestock breeding industry and low socioeconomic status. Harbin, Daqing, Qiqihar, and Songyuan are located at the southern end of Heilongjiang, and persons are in close contact with livestock, which is kept free range or housed individually there, notably in the suburban regions. Fecal shedding of E. bieneusi spores by domestic animals into the environment might be a threat to public health. Despite advances in exploring the genotypic and phylogenetic characteristics of E. bieneusi in a wide range of mammals and birds, very limited genetic data have been documented for sheep (4, 14). Our previous study reported the existence of E. bieneusi group 2 genotype BEB6 in 2 preweaned lambs (2/40 specimens [5.0%]) from the city of Suihua, northeast China (14). A closely following report described the presence of E. bieneusi group 2 genotypes BEB6, OEB1, and OEB2 in 49/72 (68.1%) fecal samples from Swedish lambs, while 37 samples from adult sheep that were older than 1 year of age were negative (10). The present study confirmed infections by E. bieneusi in 11 of 164 sheep of unspecified age (6.7%) from Harbin, 31 of 154 lambs of <1 year of age (20.1%) from Daqing, and 24 of 148 lambs of <1 year of age (16.2%) and 2 of 23 adult sheep of >1 year of age (8.7%) from Qiqihar. Here we described the detection of the organism in adult sheep and showed that there was no significant difference in infection rates between young and adult sheep. Nevertheless, the data generated clearly exhibited higher infection rates of E. bieneusi in intensively bred sheep on farms in Daqing and Qiqihar than in household sheep from Harbin. This may result from the more frequent contact among farm animals.

As shown in Table 1, household sheep from Harbin were chiefly colonized by group 1 genotypes with zoonotic potential, among which CS-4 and EbpC have been reported to be the main genotypes leading to human microsporidiosis in the same city (5). This may be attributed to the close contact of household sheep with their owners, or the animals may acquire E. bieneusi infections from human fecal sources. Genotype EbpC was also the major causative agent of E. bieneusi infections in HIV-positive and -negative individuals from Henan (6) and in infected hospitalized children from Shanghai (12). It has been documented to appear in the upper Huangpu River (a drinking water source in Shanghai) (39) and in wastewater in the cities of Qingdao, Shanghai, and Wuhan, central China (40). As summarized in Table 2, genotype EbpC, with wide host and geographic ranges, has also been found in human infections in many study areas other than China. The zoonotic importance of this genotype has been well established (4). In addition, clustering of the newly determined genotypes NESH1 to NESH3 from sheep into zoonotic group 1 is of potential zoonotic concern. To our knowledge, this is the first study to indicate the carriage of group 1 genotypes in sheep. These data suggest the possibility of zoonotic transmission of microsporidiosis between sheep and humans in northeast China.

In contrast, farm sheep from Daqing and Qiqihar were infected only with potentially host-adapted group 2 genotypes (dominantly BEB6), which may be due to the restriction from human daily activity of farm animals kept in pens or because E. bieneusi circulated only among animals. Genotype BEB6 was originally recognized as a cattle-specific genotype (32), but it seems to be more popular in sheep and deer, as shown in Table 3 (10, 14, 15). This genotype was also responsible for sporadic infections in other hosts, including monkeys, goats, and cats, as shown in Table 2 (24, 41, 42). Recently, BEB6 was found to infect a child (reported as SH5) from Shanghai and to exist in wastewater in China and Tunisia (12, 40, 43). Thus, it should be considered to have less host specificity than originally thought. In addition, two other known group 2 genotypes carried by sheep, CM7 and OEB1, appeared in previous records, in a Chinese macaque and Swedish lambs, respectively (10, 42).

TABLE 3.

Prevalences and genotype distributions of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in ruminants worldwide

| Country | Host | Prevalence (% [no. of positive animals/total no. of animals tested]) | Genotype(s)a (no. of specimens) | Group 1 genotype(s)b (no. of specimens) | Human-pathogenic genotype(s)c (no. of specimens) | % zoonotic genotypes (no. of positive specimens/total no. of specimens) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | Cattle | 14.3 (10/70) | BEB4 (1), BEB10 (1), D (1), EbpC (1), I (2), J (4) | D (1), EbpC (1) | BEB4 (1), D (1), EbpC (1), I (2), J (4) | 90.0 (9/10) | 17 |

| China | Cattle | 7.9 (70/886) | BEB4 (19), CHN3 (16), CHN4 (4), CHN11 (4), I (31), J (25) | CHN4 (4), CHN11 (4) | BEB4 (19), CHN3 (16), CHN4 (4), I (31), J (25) | 100 (96/96) | 11, 48 |

| Deer | 31.9 (29/91) | BEB6 (20), HLJD-I to HLJD-IV (1 each), HLJD-V (5) | HLJD-II (1), HLJD-III (1) | BEB6 (20) | 75.9 (22/29) | 15 | |

| Sheep | 4.4 (2/45) | BEB6 (2) | BEB6 (2) | 100 (2/2) | 14 | ||

| Yak | 7.0 (23/327) | BEB4 (16), CHN11 (4), CHN12 (1), I (1), J (1) | CHN11 (4), CHN12 (1) | BEB4 (16), I (1), J (1) | 100 (23/23) | 18 | |

| Czech Republic | Cattle | 15.4 (37/240) | I (6) | I (6) | 100 (6/6) | 19 | |

| Germany | Cattle | 11.4 (10/88) | EbpA (1), I (3), J (4), M (1), N (1) | EbpA (1), M (1) | EbpA (1), I (3), J (4) | 90.0 (9/10) | 20, 21 |

| Llama | 100 (1/1) | P (1) | P (1) | 100 (1/1) | 21 | ||

| South Korea | Cattle | 13.2 (95/718) | CEbA (1), CEbD (4), CEbF (1), D (2), I (10), IV (2), J (5) | CEbD (4), D (2), IV (2) | D (2), I (10), IV (2), J (5) | 92.0 (23/25) | 22, 23 |

| Peru | Goat | 100 (1/1) | BEB6 (1) | BEB6 (1) | 100 (1/1) | 24 | |

| Portugal | Cattle | 10.0 (5/50) | IV (3), J (1), PtEb XI (1) | IV (3) | IV (3), J (1) | 80.0 (4/5) | 25, 26 |

| Kudu | 100 (1/1) | PtEb V (1) | PtEb V (1) | 100 (1/1) | 25 | ||

| South Africa | Cattle | 18.0 (9/50) | BEB3-like (4), BEB4 (3), D (1), I (1) | D (1) | BEB4 (3), D (1), I (1) | 55.6 (5/9) | 27 |

| Spain | Goat | 14.2 (1/7) | 28 | ||||

| Sweden | Sheep | 68.1 (49/72) | BEB6 (40), OEB1 (10), OEB2 (6) | BEB6 (40) | 71.4 (40/56) | 10 | |

| USA | Cattle | 19.3 (797/4123) | BEB3 (6), BEB4 (130), BEB6 (2), BEB7 (1), BEB8 (41), BEB9 (6), I (379), IV (4), J (168), Peru 6 (1), 4948 FL-2 2004 (1) | IV (4), Peru 6 (1), 4948 FL-2 2004 (1) | BEB4 (130), BEB6 (2), I (379), IV (4), J (168), Peru 6 (1) | 92.7 (685/739) | 16, 26, 29–34 |

| Deer | 24.8 (32/129) | DeerEb1 to DeerEb13 (1 each), I (7), J (1), LW1 (1), WL4 (13), WL18 (2), WL19 (2) | LW1 (1), WL18 (2), WL19 (2) | I (7), J (1), LW1 (1) | 33.3 (13/39) | 35, 36 |

Infections by E. bieneusi have been reported for cattle from Argentina, Germany, South Korea, Portugal, South Africa, Sweden, the Czech Republic, and the United States, with infection rates ranging from 3.2% to 36.2% (16, 17, 19–23, 25–27, 29–34). Table 3 explicitly demonstrates that genotypes BEB4, I, and J represent the most common E. bieneusi genotypes in cattle, and no infection reports for these genotypes have been documented in sheep thus far. These genotypes were previously considered to be highly specific to cattle and genetically segregated from the genotypes found in humans and pigs (20). However, as shown in Table 2, like BEB6, genotypes BEB4, I, and J also have expanded host ranges, with BEB4 also infecting humans from the Czech Republic and pigs from China (11, 44), I infecting monkeys from China, deer from the United States, pigs from Spain, and cats from China (35, 41, 42, 45), and J infecting deer from the United States, chickens from Germany, and birds from Iran (35, 46, 47). A recent survey from Qinghai Province, northwest China, characterized E. bieneusi group 1 genotypes CHN11 (4/23 specimens) and CHN12 (1/23 specimens) and group 2 genotypes BEB4 (16/23 specimens), I (1/23 specimens), and J (1/23 specimens) from 7.0% (23/327 specimens) of yaks (18). Thirty-five of 793 (4.4%) cattle from Henan, Hunan, and Shandong Provinces, central China, were shown to harbor genotype I (17/35 specimens), J (9/35 specimens), BEB4 (5/35 specimens), or CHN11 (4/35 specimens), and the differences in infection rates between animals of various age groups (preweaned, postweaned, juvenile, and adult) were not significant (48). E. bieneusi also infected 35 of 93 cows (37.6%; age unknown) from Changchun, Jilin Province, northeast China (11). Single- or mixed-genotype infections with BEB4 (reported as CHN1), CHN3, CHN4, I, and J have occurred in cows, and the same genotypes were examined in Changchun children (11).

The present study identified E. bieneusi in 32 of 537 (6.0%) cattle from Songyuan, Jilin Province, and Harbin, Daqing, and Qiqihar, Heilongjiang Province, northeast China, and found a slightly higher infection rate of preweaned animals than weaned ones. Frequent mixed-genotype infections of E. bieneusi were seen in the study animals, which is likely to result from fecal cross contamination of animals that interact with each other in pens. Except for the common group 2 genotypes BEB4, I, and J found in cattle, this study also detected the group 1 genotypes CS-4, EbpC, G, and NECA1 to NECA5. It is interesting that CS-4 and EbpC were the dominant genotypes infecting cattle in Harbin, which also contributed significantly to E. bieneusi infections in children in the same study area (5). The close genetic relationship of genotypes G and NECA1 to NECA5 with many human-pathogenic genotypes in group 1 is also of potential zoonotic concern. In addition to cattle, genotype G also existed in pigs from China and Germany, horses and wild boar from the Czech Republic, and a drinking water source in China, and genotype CS-4 was found in pigs from China (4, 14, 38, 49, 50). We concluded that cattle-harbored E. bieneusi genotypes have zoonotic potential and are implicated in public health.

Besides the above-described human-pathogenic group 1 genotypes CHN4, CS-4, and EbpC, as shown in Table 4, genotypes D, EbpA, IV, and Peru6, previously reported for cattle from other locations, also represented human E. bieneusi pathogens. Together with human-pathogenic group 2 genotypes BEB4, BEB6, CHN3, I, and J, as reflected in Table 3, they accounted for the high level of potential for zoonotic transmission of microsporidiosis between sheep/cattle and humans. Nevertheless, the uncertainty of the zoonotic importance of some other ruminant-harbored group 1 genotypes (CHN11, CHN12, G, M, etc.) and group 2 genotypes (BEB3, BEB7 to BEB10, N, OEB1, OEB2, etc.) highlights the need for further efforts to fully understand the role of ruminants in transmission of human microsporidiosis.

TABLE 4.

Geographical distributions and host ranges of human-pathogenic Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in ruminants from around the world

| Genotype | Host/source (location)a | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| BEB4 | See Table 2 | See Table 2 |

| BEB6 | See Table 2 | See Table 2 |

| CHN3 | Humans (China) and cattle (China) | 11 |

| CHN4 | Humans (China) and cattle (China) | 11 |

| D | Humans (China, Congo, Cameroon, England, Gabon, Malawi, Netherlands, Niger, Nigeria, Peru, Russia, Spain, Thailand, and Vietnam), NHP (China, Kenya, Rwanda, and USA), cattle (Argentina, South Korea, South Africa, and USA), horses (Colombia), pigs (China, CZE, Japan, and USA), cats (China), dogs (China and Portugal), beavers (USA), foxes (USA and Spain), falcons (Abu Dhabi), mice (CZE and Germany), muskrats (USA), birds (Iran), raccoons (USA), otters (USA), rabbits (Spain), wild boar (Austria, CZE, and Slovak Republic), DSW (China), WW (China and Tunisia), and WWTP (Spain) | 4, 6, 12, 16, 17, 27, 36, 38–43, 45, 47, 50, 52–61 |

| EbpA | Humans (China, CZE, and Nigeria), NHP (Rwanda), cattle (Germany), pigs (China, CZE, Germany, Japan, Switzerland, and USA), horses (CZE), dogs (China), birds (Brazil), mice (CZE and Germany), wild boar (CZE and Poland), DSW (China), and WW (China) | 12, 14, 16, 38–42, 44, 50, 52, 58, 60, 62 |

| EbpC | See Table 2 | See Table 2 |

| LW1 | Humans (China), deer (USA), pigs (China), wild boar (Austria), and lake water (China) | 6, 12, 14, 35, 38, 50, 51, 58 |

| I | See Table 2 | See Table 2 |

| IV | Humans (China, Gabon, Cameroon, England, France, Malawi, Netherlands, Niger, Nigeria, Peru, and Uganda), NHP (China), cattle (South Korea, Portugal, and USA), cats (Colombia, Germany, Japan, and Portugal), dogs (China and Colombia), bears (USA), ostriches (Spain), snakes (China), squirrels (USA), voles (USA), lake water (China), and WW (China, Ireland, and Tunisia) | 4, 6, 12, 16, 36, 40–43, 45, 51, 59, 61, 63, 64 |

| J | See Table 2 | See Table 2 |

| Peru6 | Humans (Peru), cattle (USA), dogs (Portugal), birds (Portugal), and WW (China and Tunisia) | 4, 40, 43 |

CZE, Czech Republic; NHP, nonhuman primates; DSW, drinking source water; WW, wastewater; WWTP, wastewater treatment plant.

In conclusion, the results of this study confirmed the high prevalence of human-pathogenic E. bieneusi genotypes in domestic sheep and cattle from northeast China. The potential role of the study animals in zoonotic transmission of human microsporidiosis was elaborately assessed as well. An overview of the host and geographical ranges and the phylogenetic characteristics of ruminant-harbored E. bieneusi genotypes suggested a host range expansion in some group 2 genotypes previously considered to be ruminant adapted. We should be concerned about the increasing zoonotic importance of group 2 genotypes with low host specificity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the farm workers for assisting in specimen collection.

We acknowledge financial support from the 5th Heilongjiang Special Postdoctoral Research Fund (grant LBH-TZ0502), the 7th Special Financial Grant from the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant 2014T70307), the Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (grant 20122325120004), and the fund from Northeast Agricultural University (grant 2012RCA01).

REFERENCES

- 1.Mathis A, Weber R, Deplazes P. 2005. Zoonotic potential of the microsporidia. Clin Microbiol Rev 18:423–445. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.3.423-445.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vavra J, Lukes J. 2013. Microsporidia and ‘the art of living together.' Adv Parasitol 82:253–319. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407706-5.00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keeling P. 2009. Five questions about microsporidia. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000489. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santin M, Fayer R. 2011. Microsporidiosis: Enterocytozoon bieneusi in domesticated and wild animals. Res Vet Sci 90:363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang J, Song M, Wan Q, Li Y, Lu Y, Jiang Y, Tao W, Li W. 2014. Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in children in northeast China and assessment of risk of zoonotic transmission. J Clin Microbiol 52:4363–4367. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02295-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L, Zhang H, Zhao X, Zhang L, Zhang G, Guo M, Liu L, Feng Y, Xiao L. 2013. Zoonotic Cryptosporidium species and Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in HIV-positive patients on antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Microbiol 51:557–563. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02758-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matos O, Lobo ML, Xiao L. 2012. Epidemiology of Enterocytozoon bieneusi infection in humans. J Parasitol Res 2012:981424. doi: 10.1155/2012/981424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santin M, Fayer R. 2009. Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotype nomenclature based on the internal transcribed spacer sequence: a consensus. J Eukaryot Microbiol 56:34–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2008.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thellier M, Breton J. 2008. Enterocytozoon bieneusi in human and animals, focus on laboratory identification and molecular epidemiology. Parasite 15:349–358. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2008153349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stensvold CR, Beser J, Ljungstrom B, Troell K, Lebbad M. 2014. Low host-specific Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotype BEB6 is common in Swedish lambs. Vet Parasitol 205:371–374. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Wang Z, Su Y, Liang X, Sun X, Peng S, Lu H, Jiang N, Yin J, Xiang M, Chen Q. 2011. Identification and genotyping of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in China. J Clin Microbiol 49:2006–2008. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00372-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L, Xiao L, Duan L, Ye J, Guo Y, Guo M, Liu L, Feng Y. 2013. Concurrent infections of Giardia duodenalis, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, and Clostridium difficile in children during a cryptosporidiosis outbreak in a pediatric hospital in China. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7:e2437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li W, Tao W, Jiang Y, Diao R, Yang J, Xiao L. 2014. Genotypic distribution and phylogenetic characterization of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in diarrheic chickens and pigs in multiple cities, China: potential zoonotic transmission. PLoS One 9:e108279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li W, Li Y, Li W, Yang J, Song M, Diao R, Jia H, Lu Y, Zheng J, Zhang X, Xiao L. 2014. Genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in livestock in China: high prevalence and zoonotic potential. PLoS One 9:e97623. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao W, Zhang W, Wang R, Liu W, Liu A, Yang D, Yang F, Karim MR, Zhang L. 2014. Enterocytozoon bieneusi in sika deer (Cervus nippon) and red deer (Cervus elaphus): deer specificity and zoonotic potential of ITS genotypes. Parasitol Res 113:4243–4250. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-4100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santin M, Dargatz D, Fayer R. 2012. Prevalence and genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in weaned beef calves on cow-calf operations in the USA. Parasitol Res 110:2033–2041. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2732-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Del Coco VF, Cordoba MA, Bilbao G, de Almeida Castro P, Basualdo JA, Santin M. 2014. First report of Enterocytozoon bieneusi from dairy cattle in Argentina. Vet Parasitol 199:112–115. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma J, Cai J, Ma J, Feng Y, Xiao L. 2015. Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in yaks (Bos grunniens) and their public health potential. J Eukaryot Microbiol 62:21–25. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jurankova J, Kamler M, Kovarcik K, Koudela B. 2013. Enterocytozoon bieneusi in bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) infected and noninfected cattle herds. Res Vet Sci 94:100–104. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rinder H, Thomschke A, Dengjel B, Gothe R, Loscher T, Zahler M. 2000. Close genotypic relationship between Enterocytozoon bieneusi from humans and pigs and first detection in cattle. J Parasitol 86:185–188. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0185:CGRBEB]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dengjel B, Zahler M, Hermanns W, Heinritzi K, Spillmann T, Thomschke A, Loscher T, Gothe R, Rinder H. 2001. Zoonotic potential of Enterocytozoon bieneusi. J Clin Microbiol 39:4495–4499. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.12.4495-4499.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JH. 2007. Prevalence and molecular characteristics of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in cattle in Korea. Parasitol Res 101:391–396. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0468-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JH. 2008. Molecular detection of Enterocytozoon bieneusi and identification of a potentially human-pathogenic genotype in milk. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:1664–1666. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02110-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng Y, Li N, Dearen T, Lobo ML, Matos O, Cama V, Xiao L. 2011. Development of a multilocus sequence typing tool for high-resolution genotyping of Enterocytozoon bieneusi. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:4822–4828. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02803-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lobo ML, Xiao L, Cama V, Stevens T, Antunes F, Matos O. 2006. Genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in mammals in Portugal. J Eukaryot Microbiol 53(Suppl 1):S61–S64. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2006.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sulaiman IM, Fayer R, Yang C, Santin M, Matos O, Xiao L. 2004. Molecular characterization of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in cattle indicates that only some isolates have zoonotic potential. Parasitol Res 92:328–334. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-1049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abu Samra N, Thompson PN, Jori F, Zhang H, Xiao L. 2012. Enterocytozoon bieneusi at the wildlife/livestock interface of the Kruger National Park, South Africa. Vet Parasitol 190:587–590. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lores B, del Aguila C, Arias C. 2002. Enterocytozoon bieneusi (microsporidia) in faecal samples from domestic animals from Galicia, Spain. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 97:941–945. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762002000700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fayer R, Santin M, Trout JM. 2007. Enterocytozoon bieneusi in mature dairy cattle on farms in the eastern United States. Parasitol Res 102:15–20. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0746-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santin M, Fayer R. 2009. A longitudinal study of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in dairy cattle. Parasitol Res 105:141–144. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1374-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fayer R, Santin M, Macarisin D. 2012. Detection of concurrent infection of dairy cattle with Blastocystis, Cryptosporidium, Giardia, and Enterocytozoon by molecular and microscopic methods. Parasitol Res 111:1349–1355. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-2971-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santin M, Trout JM, Fayer R. 2005. Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in dairy cattle in the eastern United States. Parasitol Res 97:535–538. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-1482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santin M, Trout JM, Fayer R. 2004. Prevalence of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in post-weaned dairy calves in the eastern United States. Parasitol Res 93:287–289. doi: 10.1007/s00436-004-1132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fayer R, Santin M, Trout JM. 2003. First detection of microsporidia in dairy calves in North America. Parasitol Res 90:383–386. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-0870-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santin M, Fayer R. 2014. Enterocytozoon bieneusi, Giardia, and Cryptosporidium infecting white-tailed deer. J Eukaryot Microbiol 62:34–43. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo Y, Alderisio KA, Yang W, Cama V, Feng Y, Xiao L. 2014. Host specificity and source of Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in a drinking source watershed. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:218–225. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02997-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ministry of Health. 1998. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Ministry of Health, Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li W, Diao R, Yang J, Xiao L, Lu Y, Li Y, Song M. 2014. High diversity of human-pathogenic Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in swine in northeast China. Parasitol Res 113:1147–1153. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3752-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu Y, Feng Y, Huang C, Xiao L. 2014. Occurrence, source, and human infection potential of Cryptosporidium and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in drinking source water in Shanghai, China, during a pig carcass disposal incident. Environ Sci Technol 48:14219–14227. doi: 10.1021/es504464t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li N, Xiao L, Wang L, Zhao S, Zhao X, Duan L, Guo M, Liu L, Feng Y. 2012. Molecular surveillance of Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, and Enterocytozoon bieneusi by genotyping and subtyping parasites in wastewater. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6:e1809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karim MR, Dong H, Yu F, Jian F, Zhang L, Wang R, Zhang S, Rume FI, Ning C, Xiao L. 2014. Genetic diversity in Enterocytozoon bieneusi isolates from dogs and cats in China: host specificity and public health implications. J Clin Microbiol 52:3297–3302. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01352-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karim MR, Wang R, Dong H, Zhang L, Li J, Zhang S, Rume FI, Qi M, Jian F, Sun M, Yang G, Zou F, Ning C, Xiao L. 2014. Genetic polymorphism and zoonotic potential of Enterocytozoon bieneusi from nonhuman primates in China. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:1893–1898. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03845-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ben Ayed L, Yang W, Widmer G, Cama V, Ortega Y, Xiao L. 2012. Survey and genetic characterization of wastewater in Tunisia for Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, Cyclospora cayetanensis and Eimeria spp. J Water Health 10:431–444. doi: 10.2166/wh.2012.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sak B, Brady D, Pelikanova M, Kvetonova D, Rost M, Kostka M, Tolarova V, Huzova Z, Kvac M. 2011. Unapparent microsporidial infection among immunocompetent humans in the Czech Republic. J Clin Microbiol 49:1064–1070. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01147-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galvan-Diaz AL, Magnet A, Fenoy S, Henriques-Gil N, Haro M, Gordo FP, Miro G, del Aguila C, Izquierdo F. 2014. Microsporidia detection and genotyping study of human pathogenic E. bieneusi in animals from Spain. PLoS One 9:e92289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reetz J, Rinder H, Thomschke A, Manke H, Schwebs M, Bruderek A. 2002. First detection of the microsporidium Enterocytozoon bieneusi in non-mammalian hosts (chickens). Int J Parasitol 32:785–787. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pirestani M, Sadraei J, Forouzandeh M. 2013. Molecular characterization and genotyping of human related microsporidia in free-ranging and captive pigeons of Tehran, Iran. Infect Genet Evol 20:495–499. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma J, Li P, Zhao X, Xu H, Wu W, Wang Y, Guo Y, Wang L, Feng Y, Xiao L. 2015. Occurrence and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in dairy cattle, beef cattle and water buffaloes in China. Vet Parasitol 207:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagnerova P, Sak B, Kvetonova D, Bunatova Z, Civisova H, Marsalek M, Kvac M. 2012. Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon cuniculi in horses kept under different management systems in the Czech Republic. Vet Parasitol 190:573–577. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nemejc K, Sak B, Kvetonova D, Hanzal V, Janiszewski P, Forejtek P, Rajsky D, Kotkova M, Ravaszova P, McEvoy J, Kvac M. 2014. Prevalence and diversity of Encephalitozoon spp. and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in wild boars (Sus scrofa) in Central Europe. Parasitol Res 113:761–767. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3707-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ye J, Xiao L, Ma J, Guo M, Liu L, Feng Y. 2012. Anthroponotic enteric parasites in monkeys in public park, China. Emerg Infect Dis 18:1640–1643. doi: 10.3201/eid1810.120653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sak B, Kvac M, Kvetonova D, Albrecht T, Pialek J. 2011. The first report on natural Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon spp. infections in wild East-European house mice (Mus musculus musculus) and West-European house mice (M. m. domesticus) in a hybrid zone across the Czech Republic-Germany border. Vet Parasitol 178:246–250. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sokolova OI, Demyanov AV, Bowers LC, Didier ES, Yakovlev AV, Skarlato SO, Sokolova YY. 2011. Emerging microsporidian infections in Russian HIV-infected patients. J Clin Microbiol 49:2102–2108. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02624-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Galvan AL, Magnet A, Izquierdo F, Fenoy S, Rueda C, Fernandez Vadillo C, Henriques-Gil N, del Aguila C. 2013. Molecular characterization of human-pathogenic microsporidia and Cyclospora cayetanensis isolated from various water sources in Spain: a year-long longitudinal study. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:449–459. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02737-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wumba R, Longo-Mbenza B, Menotti J, Mandina M, Kintoki F, Situakibanza NH, Kakicha MK, Zanga J, Mbanzulu-Makola K, Nseka T, Mukendi JP, Kendjo E, Sala J, Thellier M. 2012. Epidemiology, clinical, immune, and molecular profiles of microsporidiosis and cryptosporidiosis among HIV/AIDS patients. Int J Gen Med 5:603–611. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S32344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li W, Kiulia NM, Mwenda JM, Nyachieo A, Taylor MB, Zhang X, Xiao L. 2011. Cyclospora papionis, Cryptosporidium hominis, and human-pathogenic Enterocytozoon bieneusi in captive baboons in Kenya. J Clin Microbiol 49:4326–4329. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05051-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ye J, Xiao L, Li J, Huang W, Amer SE, Guo Y, Roellig D, Feng Y. 2014. Occurrence of human-pathogenic Enterocytozoon bieneusi, Giardia duodenalis and Cryptosporidium genotypes in laboratory macaques in Guangxi, China. Parasitol Int 63:132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao W, Zhang W, Yang F, Cao J, Liu H, Yang D, Shen Y, Liu A. 2014. High prevalence of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in asymptomatic pigs and assessment of zoonotic risk at the genotype level. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:3699–3707. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00807-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ayinmode AB, Zhang H, Dada-Adegbola HO, Xiao L. 2014. Cryptosporidium hominis subtypes and Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in HIV-infected persons in Ibadan, Nigeria. Zoonoses Public Health 61:297–303. doi: 10.1111/zph.12072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sak B, Petrzelkova KJ, Kvetonova D, Mynarova A, Pomajbikova K, Modry D, Cranfield MR, Mudakikwa A, Kvac M. 2014. Diversity of microsporidia, Cryptosporidium and Giardia in mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei) in Volcanoes National Park, Rwanda. PLoS One 9:e109751. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ayinmode AB, Ojuromi OT, Xiao L. 2011. Molecular identification of Enterocytozoon bieneusi isolates from Nigerian children. J Parasitol Res 2011:129542. doi: 10.1155/2011/129542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lallo MA, Calabria P, Milanelo L. 2012. Encephalitozoon and Enterocytozoon (microsporidia) spores in stool from pigeons and exotic birds: microsporidia spores in birds. Vet Parasitol 190:418–422. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Karim MR, Yu F, Li J, Li J, Zhang L, Wang R, Rume FI, Jian F, Zhang S, Ning C. 2014. First molecular characterization of enteric protozoa and the human pathogenic microsporidian, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, in captive snakes in China. Parasitol Res 113:3041–3048. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3967-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Graczyk TK, Lucy FE, Mashinsky Y, Thompson RCA, Koru O, daSilva AJ. 2009. Human zoonotic enteropathogens in a constructed free-surface flow wetland. Parasitol Res 105:423–428. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1400-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]