Abstract

Objective

Children with acute myeloid leukemia are at risk for sepsis and organ failure. Outcomes associated with intensive care support have not been studied in a large pediatric acute myeloid leukemia population. Our objective was to determine hospital mortality of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia patients requiring intensive care.

Design

Retrospective cohort study of children hospitalized between 1999 and 2010. Use of intensive care was defined by utilization of specific procedures and resources. The primary endpoint was hospital mortality.

Setting

Forty-three children’s hospitals contributing data to the Pediatric Health Information System database.

Patients

Patients who are newly diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia and who are 28 days through 18 years old (n = 1, 673) hospitalized any time from initial diagnosis through 9 months following diagnosis or until stem cell transplant. A reference cohort of all nononcology pediatric admissions using the same intensive care resources in the same time period (n = 242,192 admissions) was also studied.

Interventions

None.

Measurements and Main Results

One-third of pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia (553 of 1,673) required intensive care during a hospitalization within 9 months of diagnosis. Among intensive care admissions, mortality was higher in the acute myeloid leukemia cohort compared with the nononcology cohort (18.6% vs 6.5%; odds ratio, 3.23; 95% CI, 2.64–3.94). However, when sepsis was present, mortality was not significantly different between cohorts (21.9% vs 19.5%; odds ratio, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.89–1.53). Mortality was consistently higher for each type of organ failure in the acute myeloid leukemia cohort versus the nononcology cohort; however, mortality did not exceed 40% unless there were four or more organ failures in the admission. Mortality for admissions requiring intensive care decreased over time for both cohorts (23.7% in 1999–2003 vs 16.4% in 2004–2010 in the acute myeloid leukemia cohort, p = 0.0367; and 7.5% in 1999–2003 vs 6.5% in 2004–2010 in the nononcology cohort, p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

Pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia frequently required intensive care resources, with mortality rates substantially lower than previously reported. Mortality also decreased over the time studied. Pediatric acute myeloid leukemia patients with sepsis who required intensive care had a mortality comparable to children without oncologic diagnoses; however, overall mortality and mortality for each category of organ failure studied was higher for the acute myeloid leukemia cohort compared with the nononcology cohort.

Keywords: acute myeloid leukemia, intensive care, multiple organ failure, neoplasms, pediatric intensive care units, sepsis

Advances in treatment regimens have improved outcomes for children with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) over the past several decades with 5-year mortality rates decreasing from over 80% in the mid-1970s to approximately 40–60% currently (1). These improvements are largely due to intensification of chemotherapy regimens, which carries the risk of increased treatment-related morbidity and mortality (2–5). Data suggest that children treated for AML are at high risk for sepsis, respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, and circulatory shock requiring inotropic support (2, 6, 7).

Initial reports of children with cancer receiving mechanical ventilation showed ICU mortality rates as high as 70–74% (8, 9). These outcomes led to wide variations in practice, presumably due to concerns regarding the appropriateness of offering intensive care to children with cancer (10–12). Although more recent studies have shown lower mortality rates in children with cancer receiving mechanical ventilation (25–65%) (13–22), these rates are substantially higher than the reported 7.2% mortality rate for a general population of mechanically ventilated children (23). Notably, among children with cancer who receive both mechanical ventilation and inotropic support, reported mortality rates have ranged from 54% to 69% (20, 24, 25).

Despite the intensity of modern AML treatment regimens, there are few contemporary data documenting the frequency of ICU care, risk of specific organ failures, and mortality in admissions requiring ICU care within this patient population. A single-center study of hospital resource utilization in children with cancer demonstrated that approximately 50% of all charges were incurred by 12.7% of patients and these patients were more likely to have AML or to have received hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) or ICU care (26). These results support the hypothesis that patients with AML are at substantial risk of treatment-related complications requiring intensive supportive care services. However, to our knowledge, there are no data on outcomes relative to need for ICU resources in pediatric patients with AML.

To address this gap in outcome data, we analyzed the Pediatric Health Information Systems (PHIS) database to study a large cohort of children treated for de novo AML prior to stem cell transplant at freestanding pediatric hospitals across the United States. The primary objective of this study was to describe the prevalence of ICU care, organ failure, sepsis, and hospital mortality rates in a homogenous pediatric AML population relative to nononcology pediatric patients. Based on our institutional experience, we hypothesized that a majority of children with AML requiring ICU care would survive but that children with AML would have higher mortality in admissions requiring ICU care than children without cancer. Furthermore, we hypothesized that among those requiring ICU care, the mortality rate would be substantially higher in children with AML who had sepsis than in the corresponding group of children without cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

A retrospective cohort study design was used. The source population consisted of patients who are 28 days old to 18 years old or younger (at the time of their index admission) hospitalized in a PHIS-contributing hospital between January 1, 1999, and March 31, 2010. Patients were excluded if hospital data were deemed invalid or incomplete by PHIS administrative standards during their hospitalization.

Data Source

Data were collected from PHIS, an administrative database containing inpatient data for over 18 million patient encounters from 43 tertiary children’s hospitals affiliated with the Child Health Corporation of America (Overland Park, KS). Contributing hospitals are located in 17 major metropolitan areas and account for 85% of all freestanding children’s hospitals in the United States registered with the National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions. The PHIS database collects demographic information, admission and discharge dates, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis and procedure codes, specific financial/utilization data (pharmacy, imaging, and clinical services), and discharge disposition. Oversight of PHIS data quality has been previously described (27).

Defining the Cohorts of Admissions

To establish the AML cohort, we identified patients with an ICD-9-CM code for any type of myeloid or unspecified leukemia (205.xx–208.xx) and excluded patients assigned an ICD-9-CM discharge diagnosis code consistent with another malignancy. To limit the population to de novo AML, patients were subsequently excluded if they received an HSCT within 60 days of index admission as this typically only occurs in the relapsed setting. Finally, the billing data for chemotherapy agents commonly used for the treatment of AML were manually reviewed for each remaining patient. Those patients who did not receive a chemotherapy regimen consistent with AML induction therapy were excluded (28). Patients entered the cohort on the day of their first hospitalization containing induction chemotherapy for AML (index admission). For each patient, all admissions starting within 9 months of index admission were included. For patients receiving HSCT more than 60 days from index admission, the HSCT admission and all subsequent admissions were excluded. As standard upfront AML therapy typically lasts 6–9 months, a 9-month study period was chosen to capture all courses of AML therapy and limit the number of relapsed patients.

The reference cohort consisted of patients who are 28 days old to 18 years old or younger with a nononcologic admission requiring ICU care (defined below) in a PHIS-contributing hospital between January 1, 1999, and March 31, 2010. An admission was excluded if it contained an ICD-9-CM code (140-0x–208.9x and 235.0x–239.9x) that indicated the presence of an oncologic condition. Neonates less than 28 days old at the time of hospitalization were excluded to limit the contribution of premature infants in a neonatal ICU to the study results. For consistency, neonates less than 28 days were also excluded from the AML cohort, resulting in exclusion of 13 neonates with AML.

Defining ICU Level of Care

An admission containing ICU care was defined by resource utilization rather than physical location, using the presence of at least one ICD-9-CM procedure code and/or clinical resource considered a priori as a marker of ICU care. These definitions were designed by the authors. Appendix 1 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/PCC/A76) lists the procedures and resources that were used to define ICU care.

Defining Organ Failure

Specific organ failures were defined by using a composite of ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes, ICD-9-CM procedure codes, and resource utilization billing codes (Appendix 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/PCC/A76). Each organ failure was dichotomized as present or absent within each admission. Sepsis was defined by a subset of previously described ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes and more recently revised codes (Appendix 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/PCC/A76) (29–34).

Variables

Demographic data were ascertained for each patient at the first day of the index admission. Age in years was analyzed both as a continuous and as a categorical variable. Insurance status was based on each patient’s index AML admission. Up to 41 ICD-9-CM procedure and discharge diagnostic codes were reviewed for each hospitalization to determine ICU care and organ failures. Length of each admission, number of admissions, and number of admissions with ICU care per patient during the study period were also calculated.

Main Outcome Measure

Hospital mortality for each admission was the main outcome measure.

Statistical Analysis

Demographics of Patient with AML were summarized by descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages for categorical variables; mean and sd, median, and range for continuous variables). AML patient’s demographics were compared between the patients with AML who had at least one admission containing ICU care and those who did not, using Pearson chi-square test for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables.

We investigated potential risk factors for mortality in AML admissions requiring ICU care. Because patients could have multiple ICU admissions, logistic regression with generalized estimating equations (GEE) method of exchangeable correlation structure was used to account for potential correlations among the admissions containing ICU care occurring for the same patient. Both univariable and multivariable regressions were constructed, and the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% CIs were reported.

The prevalence of each type of organ failure and rate of hospital mortality were described for AML and nononcology admissions containing ICU care. To compare the mortality rates and prevalence of organ failures between admissions containing AML ICU care and nononcology ICU care, we used logistic regression with GEE method to account for the potential within-subject correlations. Similar logistic regression with GEE method was used for the comparison of admissions in the two time epochs (before and after 2004). All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Human Subjects

The Institutional Review Board at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia approved the proposed research and waived informed consent.

RESULTS

AML Cohort

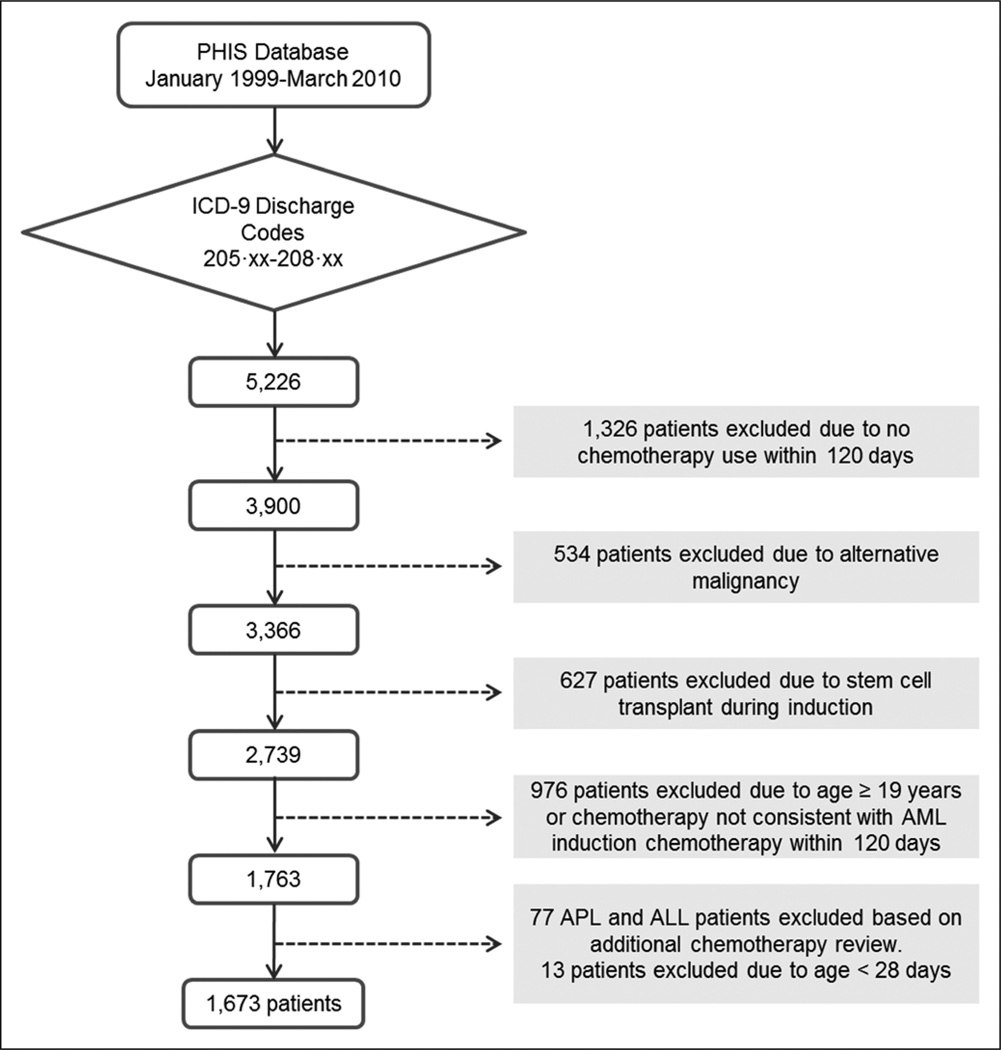

The AML cohort comprised 1,673 patients with 8,701 hospital admissions (Fig. 1). In this cohort, 553 patients (33.1%) had an admission containing ICU care. Most patients were between 1 and 15 years old (72.9%) and white (69.7%), with a slight male predominance (Table 1). AML patients with an admission containing ICU care were compared with those without such an admission (Table 1). Children 10 years old and older were significantly more likely than children less than 10 years old to receive ICU care (p < 0.0001).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. A cohort of children with de novo acute myeloid leukemia (AML) prior to stem cell transplant was defined by searching for discharge codes for myeloid or unspecified leukemia and then identifying treatment with an induction chemotherapy regimen consistent with AML therapy. PHIS = Pediatric Hospital Information System, ICD-9 = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, APL = acute promyelocytic leukemia, ALL = acute lymphocytic leukemia.

Table 1.

Comparison of Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukemia Receiving and Not Receiving Intensive Care

| Variable | All Patients (n = 1,673) (%) |

Non-ICU (n = 1,120) (%) |

ICU (n = 553) (%) |

pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, n | ||||

| ≥ 28 d and < 1 yr | 166 | 107 (9.6) | 59 (10.7) | 0.053 |

| ≥ 1 and < 3 yr | 390 | 307 (27.4) | 83 (15.0) | 0.1754 |

| ≥ 3 and < 10 yr | 394 | 294 (26.3) | 100 (18.1) | Reference |

| ≥ 10 and < 15 yr | 436 | 262 (23.4) | 174 (31.5) | < 0.0001 |

| ≥ 15 and ≤ 18 yr | 287 | 150 (13.4) | 137 (24.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Gender, n | ||||

| Male | 890 | 608 (54.3) | 282 (51.0) | Reference |

| Female | 783 | 512 (45.7) | 271 (49.0) | 0.205 |

| Race, n | ||||

| White | 1,166 | 791 (70.6) | 375 (67.8) | Reference |

| Black | 221 | 138 (12.3) | 83 (15.0) | 0.118 |

| Otherb | 286 | 191 (17.1) | 95 (17.2) | 0.732 |

| Insurance at first admission, n | ||||

| Private | 624 | 422 (37.7) | 202 (36.5) | Reference |

| Government | 653 | 442 (39.5) | 211 (38.2) | 0.982 |

| Otherc | 396 | 256 (22.9) | 140 (25.3) | 0.326 |

p value is from logistic regression.

Other includes Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian, other, and unknown.

Other includes self-pay, other, and unknown.

Comparison to Admissions Without Documentation of Malignancy

Admissions that included ICU care in the cohort of children with AML were compared over the same time period with admissions inclusive of ICU care for children without an oncologic diagnosis (Table 2). There were 674 admissions containing ICU care for 553 patients in the AML cohort, with an average of 1.2 admissions containing ICU care per patient in this group. Among 3,565,959 hospital admissions for children with no cancer diagnosis, 242,192 admissions contained ICU care for 179,667 patients.

Table 2.

Frequency of Sepsis, Organ Failure, and Mortality Among All Admissions With Intensive Care

| Variable | Total Number | Percent of Total ICU Care Admissions |

Percent Mortality (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall admissions with ICU care | |||

| AML admissions | 674 | 100.0 | 18.6 (15.6–21.5) |

| Nononcology admissions | 242,192 | 100.0 | 6.5 (6.4–6.6) |

| Sepsis | |||

| AML admissions | 319 | 47.3 | 21.9 (17.4–26.5) |

| Nononcology admissions | 20,027 | 8.3 | 19.5 (19.0–20.1) |

| Type of organ failure | |||

| Cardiovascular failure | |||

| AML admissions | 528 | 78.3 | 22.2 (18.6–25.7) |

| Nononcology admissions | 122,082 | 50.4 | 10.8 (10.6–11.0) |

| Respiratory failure | |||

| AML admissions | 347 | 51.5 | 30.6 (25.7–35.4) |

| Nononcology admissions | 189,212 | 78.1 | 7.7 (7.6–7.8) |

| Renal failure | |||

| AML admissions | 174 | 25.8 | 32.2 (25.2–39.1) |

| Nononcology admissions | 22,670 | 9.4 | 15.4 (14.9–15.9) |

| Liver failure | |||

| AML admissions | 124 | 18.4 | 35.5 (27.1–43.9) |

| Nononcology admissions | 14,945 | 6.2 | 15.2 (14.6–15.7) |

| Neurologic failure | |||

| AML admissions | 21 | 3.1 | 38.1 (17.3–58.9) |

| Nononcology admissions | 12,481 | 5.1 | 28.8 (28.0–29.6) |

| Number of organ failures | |||

| Total organ failures: 1 | |||

| AML admissions | 289 | 42.9 | 3.8 (1.6–6.0) |

| Nononcology admissions | 145,340 | 60.0 | 1.6 (1.51–1.64) |

| Total organ failures: 2 | |||

| AML admissions | 201 | 29.8 | 23.4 (17.5–29.2) |

| Nononcology admissions | 75,889 | 31.3 | 9.0 (8.8–9.2) |

| Total organ failures: 3 | |||

| AML admissions | 111 | 16.5 | 38.7 (29.7–47.8) |

| Nononcology admissions | 17,094 | 7.1 | 29.4 (28.8–30.1) |

| Total organ failures: 4 or more | |||

| AML admissions | 43 | 6.4 | 55.8 (40.9–70.7) |

| Nononcology admissions | 3,205 | 1.3 | 46.4 (44.6–48.1) |

AML = acute myeloid leukemia.

The overall mortality rate for admissions with ICU-level care in the AML cohort was 18.6% (Table 2), whereas the mortality rate for admissions with ICU care in the nononcology group was 6.5% (OR, 3.23; 95% CI, 2.64–3.93; p < 0.0001). Some of this differential in mortality rate may be related to differences in frequency of organ failure between AML and nononcology admissions. AML admissions with ICU care more frequently were associated with two or more organ failures (52.7% vs 39.7%; OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.40–1.92; p < 0.0001), and the percentage of AML admissions with ICU care characterized by cardiovascular failure was much higher than that of nononcology admissions (78.3% vs 50.4%; OR, 3.03; 95% CI, 2.49– 3.68; p < 0.0001). When comparing admissions with ICU care and a single-organ failure, mortality rates were statistically different between the AML cohort (3.8%) and nononcology cohort (1.6%) (OR, 2.45; 95% CI, 1.34–4.50; p = 0.004). Mortality was higher for AML admissions compared with nononcology admissions with ICU care for each type of organ failure studied (Table 2). For admissions with multiple organ failures in both cohorts (Table 2), mortality increased with increasing numbers of organ failures (p < 0.0001 for increasing trend within each cohort).

Within both groups, admissions requiring ICU care for sepsis resulted in higher rates of hospital mortality relative to admissions requiring ICU care without sepsis. Specifically, within AML admissions containing a sepsis event and requiring ICU care, mortality was 21.9% versus 15.5% with no sepsis (Table 3) (adjusted OR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.07–2.39; p = 0.022). However, among admissions requiring ICU care and containing a diagnosis of sepsis (Table 2), the mortality rate for the AML admissions was not significantly different from that for the nononcology admissions (21.9% vs 19.5%; OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.89–1.53; p = 0.265).

Table 3.

Hospital Mortality in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Admissions With Intensive-Level Care by Sepsis or Demographics

| Variable | Mortality (%) | ORa | pa | Adjusted ORb | Adjusted pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis | |||||

| Yes | 21.9 | 1.55 | 0.027 | 1.60 | 0.022 |

| No | 15.5 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Age at baseline | |||||

| ≥ 28 d and < 1 yr | 27.5 | 2.07 | 0.055 | 2.21 | 0.047 |

| ≥ 1 and < 3 yr | 15.8 | 0.99 | 0.978 | 0.99 | 0.986 |

| ≥ 3 and < 10 yr | 15.6 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| ≥ 10 and < 15 yr | 13.7 | 0.87 | 0.861 | 0.89 | 0.725 |

| ≥ 15 and ≤ 18 yr | 24.7 | 1.75 | 0.072 | 1.88 | 0.049 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 17.0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 20.1 | 1.22 | 0.324 | 1.26 | 0.278 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 16.9 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Black | 20.9 | 1.35 | 0.276 | 1.28 | 0.405 |

| Otherc | 22.8 | 1.48 | 0.138 | 1.47 | 0.184 |

| Insurance at first admission | |||||

| Private | 16.5 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Government | 23.6 | 1.58 | 0.046 | 1.53 | 0.088 |

| Otherd | 14.0 | 0.83 | 0.504 | 0.79 | 0.396 |

OR = odds ratio.

OR and p value from univariate generalized estimating equations (GEE) model.

Adjusted OR and p value from multivariate GEE model.

Other includes Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian, other, and unknown.

Other includes self-pay, other, and unknown.

Risk Factors for Increased Mortality

Table 3 presents the probability of mortality for AML admissions with ICU care by demographic variables and by presence of sepsis, with an adjusted analysis for all variables in the table. There was an approximately two-fold increased probability of mortality in an ICU admission for infants and for adolescents 15 years old or older (adjusted OR, 2.21; p = 0.047 and adjusted OR, 1.88; p = 0.049, respectively). Government insurance approached but did not reach statistical significance as a risk factor for increased mortality (adjusted OR, 1.53; p = 0.088). Neither gender nor race was associated with variation in mortality.

Mortality Over Time

Admissions before 2004 were compared with admissions in 2004 and later, based on the time period when AML chemotherapy regimens became more standardized toward a single regimen, which corresponded to a decrease in induction mortality (35). Although the proportion of admissions requiring ICU care remained the same in both time epochs, hospital mortality significantly decreased in the more recent time epoch in both the AML and nononcology cohorts (Table 4). The mortality for AML admissions with ICU care was 23.7% in 1999–2003 versus 16.4% in 2004–2010 (p = 0.037), and the mortality for the nononcology admissions with ICU care was 7.5% in 1999–2003 versus 6.0% in 2004–2010 (p < 0.0001).

Table 4.

ICU-Level Care and Hospital Mortality in Admissions Requiring ICU Care by Time Epoch

| Time Epoch | Total AML Admissions, n |

Total Nononcology Admissions, n |

AML ICU Admissions, n |

Nononcology ICU Admissions, n |

Hospital Mortality, AML ICU Admissions |

Hospital Mortality, Nononcology ICU Admissions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2010 | 8,701 | 4,070,720 | 674 (7.7%) | 242,192 (5.9%) | 18.5% | 6.5% |

| 1999–2003 | 2,684 | 1,301,866 | 198 (7.4%) | 78,352 (6.0%) | 23.7% | 7.5% |

| 2004–2010 | 6,017 | 2,768,854 | 467 (7.9%) | 163,840 (5.9%) | 16.4% | 6.0% |

| pa | NA | NA | 0.7218 | < 0.0001 | 0.0367 | < 0.0001 |

AML = acute myeloid leukemia, NA = not applicable.

p value is for comparison of the two time epochs.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that although one third of children with de novo AML require ICU care in the first 9 months of treatment and prior to any stem cell transplant, the mortality rate of these AML admissions containing ICU care is less than 20% and has decreased over time. Admission of an oncology patient to the PICU was previously reported to carry a dismal prognosis (8, 36), but more recent studies suggest that the survival of pediatric oncology patients can approach that of children without cancer in the ICU (14, 15, 19, 24, 37). None of these studies included large cohorts of patients with AML, often thought to have the worst prognosis for ICU survival. To our knowledge, the 18.6% hospital mortality for pediatric patients with AML requiring ICU care is the lowest reported among oncology cohorts (1, 13–22). Although direct comparison of our reported mortality rates to previous studies is limited by variation in the methodology of defining ICU care across studies, these data do suggest that, in pediatric AML, survival from admissions with ICU care continues to improve over time, similar to the improved survival described in the general pediatric oncology population. Despite this lower mortality, these data still demonstrate a difference in mortality risk when comparing the AML population with children without cancer. However, a substantial proportion of patients in both groups survived, and there is significant decrease in mortality over the two time epochs in both cohorts, an encouraging finding.

Hospital mortality in children receiving ICU care with single-organ failure in both AML and nononcology admissions was remarkably low (3.8% and 1.6%, respectively). Yet, when examining individual types of organ failure, the AML cohort had higher mortality for each type of organ failure examined (cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, liver, and neurologic). A striking finding was that among admissions identified with both sepsis and ICU care, the mortality rate did not significantly differ between patients with AML and nononcology patients, 21.9% versus 19.5%, respectively. The surprisingly low mortality rate in AML admissions with sepsis likely reflects advances in current standardized monitoring and treatment strategies for infectious complications in pediatric patients with AML, including hospitalization through neutrophil count recovery and use of prophylactic antimicrobials during periods of myelosuppression. Although prior reports describe four or more organ failures as almost universally fatal (15, 36, 37), a mortality rate of 55.8% was observed in the cohort of pediatric AML patients with four or more organ system failures. This mortality rate approaches the 46.4% mortality rate seen in the nononcology cohort with four or more organ failures.

Children with AML who are 10 years old or older were more likely to require ICU care, and admissions requiring ICU care had increased mortality for infants and older adolescents (age, 15–18 yr) compared with admissions for children who are 3 years old to less than 10 years old. This observation is consistent with previous reports of worse outcomes in older children and children under 2 years (38–40). Race and gender were not associated with an increased risk of requiring ICUlevel care or increased mortality. The absence of a disparity in mortality associated with race or gender is encouraging, given prior reports demonstrating higher treatment-related mortality in black patients (41).

These data substantively improve on previous knowledge in several ways. Prior to this study, the available data on outcomes of ICU care in pediatric patients with AML were embedded in larger studies of children with multiple cancers (8, 9, 15, 16, 36, 37). For example, the largest cohort of mechanically ventilated children with AML studied to date is only 37 patients within a larger leukemia cohort (18). In addition, prior studies were not nationally representative of freestanding pediatric hospitals, and none compared the outcomes of patients with AML with those of nononcology patients. To our knowledge, these are the first data demonstrating that pediatric AML patients with sepsis survive to discharge at a comparable rate to children without an oncologic diagnosis and that pediatric patients with AML have a substantial chance to survive admissions that involve the failure of up to four organ systems. Finally, this AML cohort is a rich resource for future investigations of risk factors for mortality in pediatric patients with AML and for comparison with other subsets of pediatric patients with cancer requiring ICU care.

Despite the strengths of PHIS data and the use of chemotherapy billing data in cohort establishment (28), this study has limitations. The definition if ICU care was based on resource utilization codes rather than physical patient location. This could lead to misclassification of patients if coding errors were present or if patients received these resources outside of the ICU. However, this strategy should decrease the potential center-level variation in ICU admission criteria and should bias toward a higher illness severity as “observation only” patients should be excluded from this analysis. Analyses were admission based rather than patient based. Additional work is needed to define patient-specific mortality probabilities for particular organ failures. Although PHIS hospitals are representative of U.S. freestanding pediatric institutions, approximately half of pediatric patients with AML are treated outside of PHIS sites (42) in institutions that treat both children and adults. Institutions with fewer pediatric patients and pediatric-specific hospital resources may have different mortality rates in admissions requiring ICU care (43). Diagnosis and reason for admission, laboratory data, information about remission status, and care limitations are not currently available through PHIS, limiting more extensive evaluation of outcomes. The use of ICD-9-CM codes to define clinical conditions has well-recognized limitations, particularly a lack of sensitivity that may vary by clinical condition and underestimation of true organ failure (34, 44–46). Given the sample size and lack of laboratory, pathology, and radiology results in PHIS, we were unable to validate the use of specific ICD-9-CM code clusters to identify individual organ failures. However, we mitigated this potential problem by using a previously validated methodology for cohort definition (28). Furthermore, to define sepsis, we used a subset of the ICD-9-CM codes originally validated by Angus et al (29) and Watson et al (30) that has been shown to have high positive predictive value for sepsis (32), updated with more recent sepsis-specific codes (31). Most importantly, the overall limitations of ICD-9-CM codes should not be different for the AML and nononcology cohorts as the same methodology was applied to both, yielding little impact on comparisons between the two groups.

CONCLUSIONS

We have demonstrated that hospital admissions for children with AML frequently require ICU-level care and that mortality in such admissions is substantially lower than previously reported. Furthermore, pediatric AML patients with sepsis survive to discharge at a comparable rate to children without an oncologic diagnosis, and overall hospital mortality is decreasing over time. Future work should focus on patient-specific survival probabilities in pediatric AML and in other pediatric malignancies, including analysis of the impact of duration of ICU resource utilization, such as duration of mechanical ventilation or vasoactive medication use, on outcome; analysis of the outcomes of pediatric patients with AML after relapse and after stem cell transplantation; and identifying modifiable risk factors to further improve the outcomes of pediatric AML therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was performed at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Dr. Maude is supported by the Abramson Cancer Center’s Paul Calabresi Career Development Award K12 CA076931 from the National Institutes of Health and the When Everyone Survives Foundation. Dr. Fisher is currently receiving a grant from Pfizer. Dr. Seif received an Alex’s Lemonade Stand/Center for Childhood Cancer Research Seed Grant for this study. She is currently receiving grants from the Canuso Foundation, the American Society of Blood & Marrow Transplantation, and the American Cancer Society. Dr. Kavcic receives research funding from the Slovenian Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sport (grant J3-4220). Dr. Zaoutis is a consultant for Merck, Pfizer, Astellas, Hemocue, and Cubist and is currently receiving a grant from Merck. Dr. Nadkarni is currently receiving grant support from Laerdal. Dr. Thomas is on the Scientific Advisory Board for Discovery Laboratories. Dr. Aplenc received grant R01 CA165277 from National Institutes of Health for this study.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/pccmjournal).

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith MA, Seibel NL, Altekruse SF, et al. Outcomes for children and adolescents with cancer: Challenges for the twenty-first century. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2625–2634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Creutzig U, Zimmermann M, Reinhardt D, et al. Early deaths and treatment-related mortality in children undergoing therapy for acute myeloid leukemia: Analysis of the multicenter clinical trials AML-BFM 93 and AML-BFM 98. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4384–4393. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riley LC, Hann IM, Wheatley K, et al. Treatment-related deaths during induction and first remission of acute myeloid leukaemia in children treated on the Tenth Medical Research Council acute myeloid leukaemia trial (MRC AML10). The MCR Childhood Leukaemia Working Party. Br J Haematol. 1999;106:436–444. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubnitz JE, Lensing S, Zhou Y, et al. Death during induction therapy and first remission of acute leukemia in childhood: The St. Jude experience. Cancer. 2004;101:1677–1684. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slats AM, Egeler RM, van der Does-van den Berg A, et al. Causes of death–other than progressive leukemia–in childhood acute lymphoblastic (ALL) and myeloid leukemia (AML): The Dutch Childhood Oncology Group experience. Leukemia. 2005;19:537–544. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson BE, Webb DK, Howman AJ, et al. United Kingdom Childhood Leukaemia Working Group and the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group: Results of a randomized trial in children with acute myeloid leukaemia: Medical research council AML12 trial. Br J Haematol. 2011;155:366–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perel Y, Auvrignon A, Leblanc T, et al. French LAME (Leucémie Aiguë Myéloblastique Enfant) Cooperative Group: Treatment of childhood acute myeloblastic leukemia: Dose intensification improves outcome and maintenance therapy is of no benefit–multicenter studies of the French LAME (Leucémie Aiguë Myéloblastique Enfant) Cooperative Group. Leukemia. 2005;19:2082–2089. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butt W, Barker G, Walker C, et al. Outcome of children with hematologic malignancy who are admitted to an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1988;16:761–764. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198808000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heney D, Lewis IJ, Lockwood L, et al. The intensive care unit in paediatric oncology. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67:294–298. doi: 10.1136/adc.67.3.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodman DM, Wilde RA, Green TP. Oncology patients in the pediatric intensive care unit: Room for optimism? Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3768–3769. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200011000-00051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orlowski JP, McHugh MJ, Lockrem JD. Outcome of children with hematologic malignancy. Crit Care Med. 1989;17:847. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198908000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Randolph AG, Zollo MB, Egger MJ, et al. Variability in physician opinion on limiting pediatric life support. Pediatrics. 1999;103:e46. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.4.e46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dursun O, Hazar V, Karasu GT, et al. Prognostic factors in pediatric cancer patients admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31:481–484. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181a330ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hallahan AR, Shaw PJ, Rowell G, et al. Improved outcomes of children with malignancy admitted to a pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3718–3721. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200011000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heying R, Schneider DT, Körholz D, et al. Efficacy and outcome of intensive care in pediatric oncologic patients. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:2276–2280. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keengwe IN, Stansfield F, Eden OB, et al. Paediatric oncology and intensive care treatments: Changing trends. Arch Dis Child. 1999;80:553–555. doi: 10.1136/adc.80.6.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyer S, Gottschling S, Biran T, et al. Assessing the risk of mortality in paediatric cancer patients admitted to the paediatric intensive care unit: A novel risk score? Eur J Pediatr. 2005;164:563–567. doi: 10.1007/s00431-005-1695-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinbach D, Wilhelm B, Kiermaier HR, et al. Long term survival in children with acute leukaemia and complications requiring mechanical ventilation. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:1026–1032. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.205567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamburro RF, Barfield RC, Shaffer ML, et al. Changes in outcomes (1996–2004) for pediatric oncology and hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9:270–277. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31816c7260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Veen A, Karstens A, van der Hoek AC, et al. The prognosis of oncologic patients in the pediatric intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:237–241. doi: 10.1007/BF01712243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ha EJ, Kim S, Jin HS, et al. Early changes in SOFA score as a prognostic factor in pediatric oncology patients requiring mechanical ventilatory support. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010;32:e308–e313. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181e51338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owens C, Mannion D, O’Marcaigh A, et al. Indications for admission, treatment and improved outcome of paediatric haematology/oncology patients admitted to a tertiary paediatric ICU. Ir J Med Sci. 2011;180:85–89. doi: 10.1007/s11845-010-0634-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Payen V, Jouvet P, Lacroix J, et al. Risk factors associated with increased length of mechanical ventilation in children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:152–157. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182257a24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dalton HJ, Slonim AD, Pollack MM. Multicenter outcome of pediatric oncology patients requiring intensive care. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;20:643–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiser RT, West NK, Bush AJ, et al. Outcome of severe sepsis in pediatric oncology patients. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:531–536. doi: 10.1097/01.pcc.0000165560.90814.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenman MB, Vik T, Hui SL, et al. Hospital resource utilization in childhood cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27:295–300. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000168724.19025.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Narus SP, Srivastava R, Gouripeddi R, et al. Federating clinical data from six pediatric hospitals: Process and initial results from the PHIS+Consortium. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:994–1003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kavcic M, Fisher BT, Torp K, et al. Assembly of a cohort of children treated for acute myeloid leukemia at free-standing children’s hospitals in the United States using an administrative database. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:508–511. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: Analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watson RS, Carcillo JA, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. The epidemiology of severe sepsis in children in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:695–701. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-682OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall MJ, Williams SN, DeFrances CJ, et al. Inpatient care for septicemia or sepsis: A challenge for patients and hospitals. NCHS Data Brief. 2011;62:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, et al. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1546–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Odetola FO, Gebremariam A, Freed GL. Patient and hospital correlates of clinical outcomes and resource utilization in severe pediatric sepsis. Pediatrics. 2007;119:487–494. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss SL, Parker B, Bullock ME, et al. Defining pediatric sepsis by different criteria: Discrepancies in populations and implications for clinical practice. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:e219–e226. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31823c98da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kavcic M, Fisher BT, Li Y, et al. Induction mortality and resource utilization in children treated for acute myeloid leukemia at freestanding pediatric hospitals in the United States. Cancer. 2013;119:1916–1923. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sivan Y, Schwartz PH, Schonfeld T, et al. Outcome of oncology patients in the pediatric intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 1991;17:11–15. doi: 10.1007/BF01708402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ben Abraham R, Toren A, Ono N, et al. Predictors of outcome in the pediatric intensive care units of children with malignancies. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2002;24:23–26. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lange BJ, Smith FO, Feusner J, et al. Outcomes in CCG-2961, a children’s oncology group phase 3 trial for untreated pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: A report from the children’s oncology group. Blood. 2008;111:1044–1053. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-084293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Razzouk BI, Estey E, Pounds S, et al. Impact of age on outcome of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: A report from 2 institutions. Cancer. 2006;106:2495–2502. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Molgaard-Hansen L, Möttönen M, Glosli H, et al. Nordic Society of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology (NOPHO): Early and treatment-related deaths in childhood acute myeloid leukaemia in the Nordic countries: 1984–2003. Br J Haematol. 2010;151:447–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Children's Oncology Group. Aplenc R, Alonzo TA, Gerbing RB, et al. Ethnicity and survival in childhood acute myeloid leukemia: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Blood. 2006;108:74–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aplenc R, Fisher BT, Huang YS, et al. Merging of the National Cancer Institute-funded cooperative oncology group data with an administrative data source to develop a more effective platform for clinical trial analysis and comparative effectiveness research: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(Suppl 2):37–43. doi: 10.1002/pds.3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Randolph AG, Gonzales CA, Cortellini L, et al. Growth of pediatric intensive care units in the United States from 1995 to 2001. J Pediatr. 2004;144:792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Howard AE, Courtney-Shapiro C, Kelso LA, et al. Comparison of 3 methods of detecting acute respiratory distress syndrome: Clinical screening, chart review, and diagnostic coding. Am J Crit Care. 2004;13:59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quan H, Li B, Saunders LD, et al. IMECCHI Investigators: Assessing validity of ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data in recording clinical conditions in a unique dually coded database. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:1424–1441. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00822.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waikar SS, Wald R, Chertow GM, et al. Validity of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification Codes for Acute Renal Failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1688–1694. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.