Abstract

Introduction

NR4A1 (TR3, Nur77) is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily of transcription factors and there is evidence that this receptor is highly expressed in multiple tumor types. Moreover, RNA interference studies indicate that NR4A1 exhibits growth promoting, angiogenic and prosurvival activity in most cancers.

Areas Covered

This review summarizes studies on several apoptosis-inducing agents that activate nuclear export of NR4A1 which subsequently forms a mitochondrial NR4A1-bcl-2 complex that induces the intrinsic pathway for apoptosis. Cytosporone B and related compounds that induce NR4A1-dependent apoptosis in cancer cells through both modulation of nuclear NR4A1 and nuclear export are also discussed. A relatively new class of diindolylmethane analogs (C-DIMs) including 1,1-bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-methoxyphenyl)methane (DIM-C-pPhOCH3) (NR4A1 activator) and 1,1-bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-hydroxyphenyl)methane (DIM-C-pPhOH) (NR4A1 deactivator) are discussed in more detail. These anticancer drugs (C-DIMs) act strictly through nuclear NR4A1 and induce apoptosis in cancer cells and tumors.

Expert Opinion

It is clear that NR4A1 plays an important pro-oncogenic role in cancer cells and tumors, and there is increasing evidence that this receptor can be targeted by anticancer drugs that induce cell death via NR4A1-dependent and -independent pathways. Moreover, since many of these compounds exhibit relatively low toxicity, they represent an important class of mechanism-based anticancer drugs with excellent potential for clinical applications.

1. Introduction

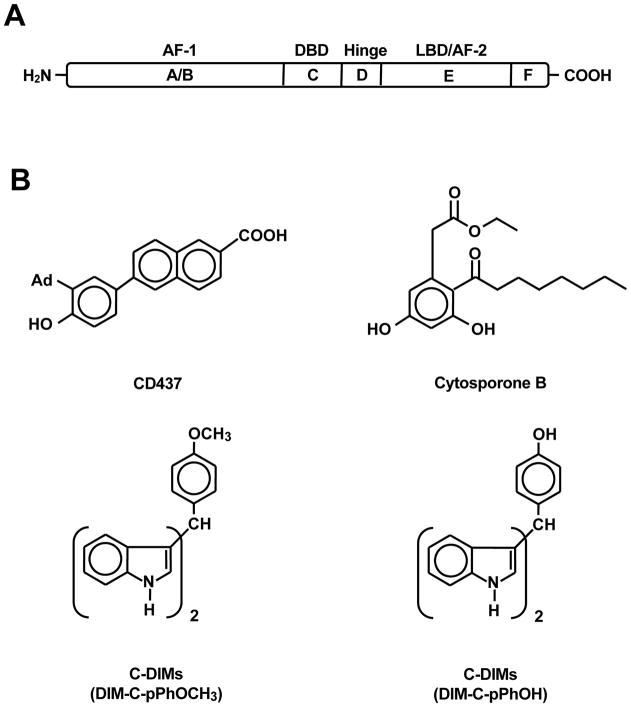

The nuclear receptor (NR) superfamily of transcription factors contains 48 members which exhibit significant structural similarities [1–4]. NRs contain an N-terminal domain (A/B), zinc finger DNA-binding domain (C), an adjacent hinge (D), and a C-terminal ligand-binding domain (E/F), and both N- and C-terminal domains may also contain activation functions (AFs) necessary for transactivation. NRs have been divided into three major classes which include endocrine receptors which have known endogenous ligands, adopted orphan receptors which have endogenous or synthetic ligands, and orphan receptors for which no endogenous ligands have been identified [5]. NR4A receptors are a subset of adopted orphan receptors which include NR4A1 (Nur77, TR3, NGFI-B), NR4A2 (Nurr1) and NR4A3 (NOR-1); these receptors exhibit 91–95% and approximately 50% homology in their DNA binding and C-terminal ligand binding domains, respectively, but have different N-terminal domains [6–8]. NR4A receptors are early-immediate genes induced by stimuli/stressors and their function in cellular homeostasis are continually being identified [9, 10]. In addition, NR4A receptors and particularly NR4A1 are important in carcinogenesis and these orphan receptors are exciting and novel targets for development of new mechanism-based anticancer drugs [11].

2. Expression and Function of NR4A1 in Cancer Cells and Tumors

A systematic study of NR4A1 expression in multiple human tumors has not been determined; however, Immunostaining of pancreatic, bladder and colon tumors and non-tumor tissues show that expression is higher in tumors [12–15]. For example, 80% of human pancreatic tumors exhibited moderate to high immunostaining for NR4A1, whereas in approximately 80% of non-tumor pancreatic tissues, the receptor could not be detected [15]. In a carcinogen-induced mouse colon tumor model, NR4A1 was induced in the tumors but not in surrounding non-tumor tissue, suggesting a possible role for NR4A1 in colon tumorigenesis [14]. The overexpression of NR4A1 in human and murine tumors is consistent with the expression of this receptor in cells derived from breast, lung, colon, prostate, bladder, pancreatic, gastric, ovarian, melanoma, neuronal, and cervical tumors [12–25]. Knockdown or overexpression of NR4A1 has also provided insights on NR4A1 function in various cancer cell lines. For example, knockdown of NR4A1 in pancreatic cancer cells decreases cell growth and induces apoptosis and this is accompanied by downregulation of survivin and bcl-2 and induction of caspase-3 and PARP cleavage [15]. Results of knockdown or overexpression of NR4A1 in cervical, lymphoma, lung and colon cancer and melanoma cells suggest that this receptor exhibits pro-oncogenic activity and enhances either survival and/or cell proliferation [14, 22, 23, 26, 27] and decreased expression also inhibited cancer cell transformation [23]. There is also evidence that NR4A1 plays an important role in angiogenesis in human umbilical vein endothethial cells and gastrointestinal tumors [28, 29]. NR4A1 also inhibited retinoid-induced anticancer activity in lung cancer cells and this activity may be due, in part, to inhibition of RXR signaling [30, 31]. In contrast, overexpression of NR4A1 in breast cancer cell lines inhibited cancer cell migration and this correlated with the low expression of this receptor in more highly metastatic mammary tumors [24]. Microarray studies of several solid tumors showed that NR4A1 mRNA levels were decreased in metastatic human lung, breast, prostate, colorectal, uterine and ovarian tumors compared to primary tumors [32]. Thus, the pro-oncogenic activity and expression levels of NR4A1 mRNA or protein may be variable and dependent on tumor type, cell context and tumor stage, and further research is required to resolve these issues.

3. NR4A1 as a Drug Target via Nuclear Export

Zhang has summarized a novel and exciting drug-dependent pro-apoptotic pathway associated with nuclear export of NR4A1 [11]. 6-[3-(1-Adamantyl)-4-hydroxyphenyl]-2-naphthalene carboxylic acid (AHPN or CD437) is a caged retinoid (Fig. 1) that induces NR4A1 expression in cancer cell lines and this is accompanied by cancer cell death [16, 17, 27, 30, 31, 33–37]. Drug-induced apoptosis is not due to direct binding to NR4A1 and is independent of retinoic acid receptors but is abrogated after knockdown of NR4A1 [11]. Overexpression of wild-type and deletion variant forms of NR4A1 demonstrated that CD437-induced apoptosis was not dependent on the DNA-binding domain of NR4A1 but was blocked by leptomycin B, an inhibitor of nuclear protein export [35, 37]. Subsequent studies showed that drug-induced nuclear export of NR4A1 resulted in formation of a pro-apoptotic mitochondrial NR4A1-bcl-2 complex which induced opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore channel, release of cytochrome c, and subsequent activation of the apoptosome [35, 37]. NR4A1 interaction with bcl-2 induced a conformation change in bcl-2, resulting in exposure of its BH3 domain which is required for apoptotic activity. Kolluri and coworkers [38] have identified a nonapeptide derived from NR4A1 which interacts with bcl-2 and exposes the BH3 domain to convert bcl-2 into an apoptotic complex, and Paclitaxel, a taxane-derived anticancer drug, exhibits similar activity [39]. These results clearly demonstrate important new concepts for inducing apoptosis in cancer cells in which NR4A1 mimics can be developed for future clinical applications.

Figure 1.

(A) Domain structure of NR4A1 and (B) structures of various ligands that activate or deactivate NR4A1.

Moreover, a large number of agents that activate apoptosis also induce NR4A1 expression and/or export, and these include 5-fluorouracil, sulindac, HDAC inhibitors, calcium ionophores, cadmium, tin derivatives, cytosporone B (Fig. 1) and related analogs, n-butylenephthalide, acetylshikonin derivatives, phorbol ester (TPA), butyrate, viruses, VP16, insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 (IGFBP3), and synthetic chenodeoxycholic acid derivatives, [18, 19, 40–48]. Moreover, in colon cancer cells, butyrate-induced apoptosis was associated with nuclear export of NR4A1 to the cytosol and not mitochondria [41]. These results demonstrate the complexity of drug-induced apoptosis that is related to nuclear export of NR4A1 and further studies are required to define these pathways and undoubtedly this will result in new approaches for anticancer drug development.

Cytosporone B (CsnB) (Fig. 1) and related compounds represent a novel subclass of NR4A1-dependent pro-apoptotic compounds in cancer cells [49, 50]. CsnB induces NR4A1 expression and this is accompanied by nuclear export of the receptor; however, the function of extranuclear NR4A1 has not been fully investigated. In contrast, to other apoptosis-inducing agents such as CD437, CsnB binds to nuclear NR4A1 and decreases expression of brain- and reproductive organ-expressed (BRE) protein, an anti-apoptotic protein [49]. This response is due to altered transcription of BRE by the liganded nuclear receptor, demonstrating the CsnB and related compounds modulate NR4A1-dependent extranuclear and nuclear pathways.

Although the pathways associated with nuclear export of NR4A1 to mitochondria and subsequent apoptosis have been well documented [11], the factors required for nuclear NR4A1 export and the extranuclear location of the receptor may be cell context and drug-dependent. For example, in different cell lines, there is some variability with respect to specific kinases and the requirement for RXR in mediating nuclear export of NR4A1 [17, 19, 27, 33, 34, 51–55]. One study showed that in gastric cancer cells, both RXRα and NR4A1 were both localized in the nucleus and after treatment with 9-cis-retinoic acid, both receptors were translocated from the nucleus to the cytoplasm [51]. NR4A1 subsequently becomes associated with mitochondria but RXRα was not required for mitochondrial-NR4A1 interactions. RXR was also required for nuclear-mitochondrial targeting of NR4A1 in LNCaP and HEK293T cells [33]; however, in this study, the RXR-NR4A1 heterodimer interacted with mitochondria and 9-cis-retinoic acid inhibited the response. Thus, the effects of the RXR agonist 9-cis-retinoic acid were remarkably dependent on cell context. Trans-retinoic acid inhibited growth but did not induce apoptosis (or NR4A1 expression) or nuclear export of NR4A1 in gastric cancer cells and it was concluded that the growth inhibition was due to nuclear NR4A1 [19]. In contrast, the synthetic retinoid, fenretinide induced apoptosis in liver cancer cells and this was due to induction of NR4A1 and its subsequent interaction with mitochondria [55].

The interplay between retinoids and their receptors clearly plays an important role in NR4A1 nuclear export and interactions with mitochondria that results in induction of apoptosis. Recent studies in hepatocellular carcinoma demonstrate a proapoptotic role for NR4A1 which resembles the drug-induced responses noted above [56, 57]. The chromodomain helicase/adenosine triphosphatase DNA binding protein 1-like (CHD1L) gene exhibits oncogenic activity for hepatocellular carcinoma and enhances survival of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. This activity of CHD1L has been linked to interactions with nuclear NR4A1 and inhibition of NR4A1 nuclear export and subsequent receptor-mediated apoptosis [56, 57], demonstrating ligand-independent regulation of the apoptotic activity of NR4A1 through expression of an endogenous gene.

4. Nuclear NR4A1 as a Drug Target

4.1 Modulation of nuclear receptor-dependent activity by analogs of 1,1-bis(3′-indolyl)methane (DIM)

1,1-Bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-substituted phenyl)methanes (C-DIMs) (Fig. 1) are triarylmethane derivatives of 1,1-bis(3′-indolyl)methane (DIM) which is an acid-catalyzed metabolite of indole-3-carbinol (I3C), a major chemoprotective phytochemical present in cruciferous vegetables [58, 59]. Both DIM and I3C exhibit a broad spectrum of anticancer activities in multiple tumor types, and DIM binds and activates/inactivates the estrogen, androgen and aryl hydrocarbon (AhR) receptors [60–64]. Methylene-substituted DIMs (C-DIMs) were initially synthesized in this laboratory during studies on DIM and several ring-substituted DIMs as AhR agonists and partial antagonists and the C-DIMs served as negative controls since it was assumed that addition of the bulky phenyl substituent would abrogate AhR binding. C-DIMs did not bind the AhR; however, initial testing showed that like DIM, several C-DIM analogs inhibit carcinogen-induced rat mammary tumor growth [65]. A screening set of C-DIMs containing different para-substituents identified the p-trifluoromethyl (DIM-C-pPhCF3), t-butyl (DIM-C-pPhtBu), phenyl (DIM-C-pPhC6H5), and cyano (DIM-C-pPhCN) analogs as activators of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) that inhibited growth of breast, colon, bladder, ovarian, cervical, endometrial, prostate, lung, pancreatic and kidney cancer cells and/or tumors in murine xenograft or orthotopic models [65–77]. It was also observed that most of anticancer activities of PPARγ-active C-DIMs were receptor-independent and involved perturbation of mitochondria [67], induction of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [78–80], and activation of multiple kinase pathways including stress kinases [71, 78–81]. However, the receptor-dependent and -independent activities of PPARγ-active C-DIMs did not account for the potent anticancer activities of other C-DIM analogs, and this has resulted in identification of other receptors targeted by C-DIMs.

4.2 Activation of nuclear NR4A1

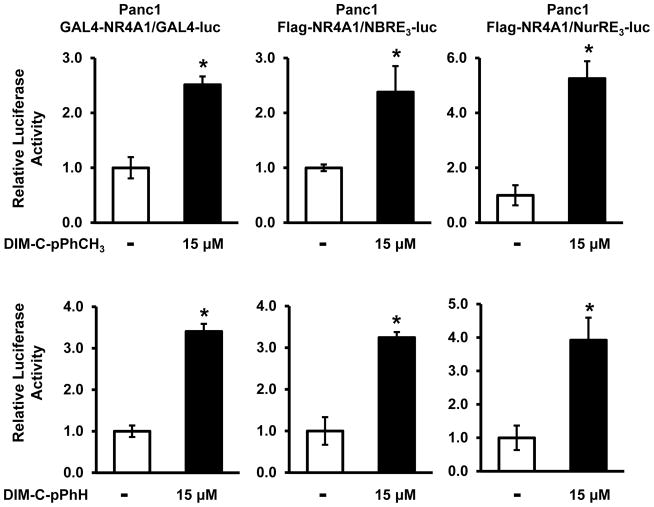

The limited role of PPARγ in mediating the anticancer activities of C-DIMs prompted further studies on the potential role of other NRs in mediating the effects of these compounds in cancer cell lines. The same set of C-DIM compounds was used for screening several orphan receptors that are linked to pro-apoptotic/growth inhibitory pathways. Results of transactivation studies using mouse GAL4-Nr4a1 constructs [82] identified C-DIMs that activated Nr4a1 [12, 13, 83], and the p-methoxy derivative (DIM-C-pPhOCH3) has been used as a prototype. Transfection with the mouse constructs resulted in relatively high induction responses; however, using GAL4-NR4A1 (human) chimeras, DIM-C-pPhOCH3 and DIM-C-pPhH induced only a 2- to 3-fold response in Panc1 cells and similar results were observed using NBRE-luc and NuRE-luc constructs (Fig. 2). The NBRE-luc construct contains three tandem AAGGTCA sequences linked to a luciferase reporter gene and the NuRE-luc construct contains three tandem pro-opiomelanocortin Nur77 response elements (TGATATTTACCTCCAAATGCCA) linked to a luciferase reporter gene. The NBRE and NuRE sequences bind NR4A1 as a monomer and homodimer, respectively [84, 85]. Like other C-DIMs, DIM-C-pPhOCH3 induced receptor-independent pro-apoptotic responses [86]; however, treatment of bladder, colon and pancreatic cancer cells with this compound enhanced expression of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), a death receptor ligand, and transfection with a small inhibitory RNA against NR4A1 (siNR4A1) decreased induction of TRAIL [12, 13, 83]. In contrast to results obtained with CD437 and other apoptosis-inducing agents, DIM-C-pPhOCH3 did not enhance expression of NR4A1 and did not induce nuclear export of this receptor. DIM-C-pPhOCH3-induced apoptosis was also observed in the presence or absence of leptomycin B, confirming that NR4A1-dependent responses were due to nuclear localization of the receptor. Moreover, the induction of growth inhibitory/pro-apoptotic genes by DIM-C-pPhOCH3 was accompanied by inhibition of growth and induction of apoptosis in cancer cell lines and tumors [12, 13, 83, 86].

Figure 2.

Activation of GAL4-NR4A1 (human)/GAL4-luc and NuRE-luc and NBRE3-luc (cotransfected with FLAG-NR4A1) by DIM-C-pPhOCH3 and DIM-C-pPhH. *, Significant (p<0.05) induction is indicated.

p21 expression was induced in pancreatic cancer cells treated with DIM-C-pPhOCH3 and transfection with siNR4A1 decreased the induction response [87]. However, inspection of the p21 promoter did not reveal putative NuREs or NBREs and deletion analysis of the promoter showed that the proximal GC-rich region of the promoter was NR4A1-responsive. RNA interference and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays showed that induction of p21 in pancreatic cancer cells by DIM-C-pPhOCH3 was associated with formation of an NR4A1/Sp1 and NR4A1/Sp4 complex bound to the proximal GC-rich promoter of the p21 gene [87]. These results are comparable to induction of p21 by PPARγ/Sp4 interaction with the GC-rich promoter region [67] and this mechanism of p21 activation has been observed for other NRs [88–90].

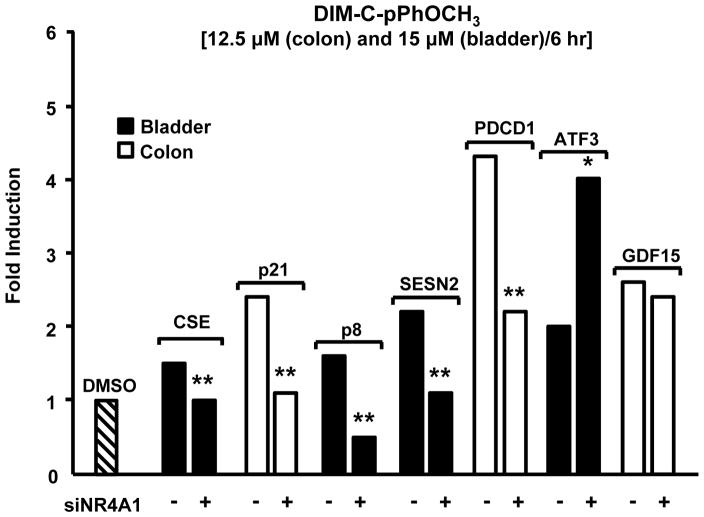

Microarray experiments in bladder, prostate, colon and pancreatic cancer cells show that DIM-C-pPhOCH3 induced genes were associated with growth inhibition, apoptosis, metabolism and homeostasis, signal transduction, protein folding, stress, transport and other functional categories and a similar diversity of induced gene functional groups were observed in other cancer cell lines [12, 13 and unpublished results]. Only 19 genes were induced by DIM-C-pPhOCH3 in all 4 cell lines (Table 1) and the receptor-dependent and -independent activation/deactivation of these genes is currently being investigated. The role of NR4A1 in mediating induction of selected pro-apoptotic/growth inhibitory genes in colon and bladder cancer cells has been investigated by RNA interference (Fig. 3) [12, 13]. Induction of these genes by DIM-C-pPhOCH3 is cell context-dependent and with the exception of GDF15 (NAG-1) and ATF3, transfection of siNR4A1 significantly decreased induction of the cystathionase (CSE), p21, p8, sestrin 2 (SESN2) and programmed cell death 1 (PDCD1) genes in one or both cell lines. Surprisingly, NR4A1 knockdown enhanced ATF3 expression indicating that the receptor may constitutively repress ATF3, whereas induction of GDF15 by DIM-C-pPhOCH3 is receptor-independent. Induction of CSE by DIM-C-pPhOCH3 was NR4A1-dependent in bladder but NR4A1-independent in colon cancer cells [12, 13]. Thus, induction of NR4A1-dependent genes by DIM-C-pPhOCH3 was highly dependent on the cancer cell line, and differences were observed in cell lines derived from the same tumor (e.g. colon) [13]. Nevertheless, DIM-C-pPhOCH3 and related C-DIMs represent the first group of compounds that activate nuclear NR4A1 and current studies are focused on identification of new agonists, NR4A1-regulated genes, and the mechanisms of receptor-dependent activation or deactivation.

Table 1.

Genes significantly induced or repressed after treatment of bladder, pancreatic, colon and prostate cancer cells with DIM-C-pPhOCH3 for 2 or 6 hr.

| Gene | Modulation after 2 or 6 hr (DMSO = 1.0) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder | Pancreatic | Prostate | Colon | |

| TNF receptor-associated factor 5 (TRAF5) | 0.63/0.26 | 0.57/0.57 | 0.84/0.72 | 0.69/0.64 |

| DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily B, member 9 (DNAJB9) | 1.34/4.31 | 1.81/5.48 | 0.89/0.70 | 1.04/1.59 |

| Cyclin E2 (CCNE2) | 0.90/0.32 | 0.88/0.52 | 0.96/0.30 | 0.93/0.43 |

| Thyroid hormone receptor interactor 10 (TRIP10) | 0.77/0.67 | 0.81/0.52 | 0.68/0.47 | 0.78/0.71 |

| Thioredoxin interacting protein (TXNIP) | 1.40/2.87 | 0.65/1.17 | 0.39/0.52 | 0.57/0.88 |

| Sema domain, immunoglobulin domain (Ig), transmembrane domain (TM) and short cytoplasmic domain, (semaphorin) 4D (SEMA4D) | 0.90/0.51 | 0.78/0.54 | 0.95/0.73 | 1.00/0.82 |

| CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), beta (CEBPB) | 1.45/3.61 | 1.39/2.73 | 0.94/1.98 | 1.06/2.66 |

| Regulator of G-protein signaling 19 (RGS19) | 0.99/1.28 | 0.84/0.69 | 0.66/0.54 | 0.70/0.63 |

| Heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 (HMOX1) | 1.25/2.67 | 1.41/2.87 | 0.97/2.05 | 1.02/2.43 |

| Flap structure-specific endonuclease (FEN1) | 0.88/0.59 | 0.95/0.71 | 0.88/0.38 | 0.65/0.46 |

| Sestrin 2 (SESN2) | 1.65/4.59 | 1.65/3.67 | 0.99/2.56 | 1.34/2.96 |

| Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 3 (LAMP3) | 1.14/1.60 | 1.08/1.14 | 0.80/3.05 | 1.88/1.93 |

| Jagged 2 (JAG2) | 0.97/0.42 | 0.69/0.41 | 0.80/0.37 | 0.87/0.60 |

| Growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) | 5.58/22.74 | 1.83/3.71 | 1.87/5.08 | 1.13/1.83 |

| Protein phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 15A (PPP1R15A) | 1.87/2.35 | 2.88/2.34 | 1.00/1.94 | 1.60/2.62 |

| Ras association (RalGDS/AF-6) domain family 5 (RASSF5) | 1.04/1.50 | 1.08/0.51 | 1.02/0.45 | 0.80/0.42 |

| Jun dimerization protein 2 (JCP2) | 1.02/1.84 | 0.85/1.19 | 1.03/5.16 | 1.09/3.33 |

| Three prime repair exonuclease 1 (TREX1) | 0.91/0.62 | 0.90/0.68 | 0.80/0.53 | 0.87/0.67 |

| Class II bHLH protein MIST1 (MIST1) | 1.04/1.63 | 0.94/5.09 | 0.75/0.45 | 1.10/0.79 |

Figure 3.

Effects of siNR4A1 on DIM-C-pPhOCH3-inducible genes in colon and bladder cancer cells [12, 13]. Significant (p<0.05) decreases (*) or increases (*) are indicated.

4.3 Deactivation of nuclear NR4A1

The hydroxyl C-DIM analog (DIM-C-pPhOH) (Fig. 1) did not activate GAL4-NR4A1 in initial studies and appeared to exhibit receptor antagonist activities in several assays [15, 83]. Unlike DIM-C-pPhOCH3, the hydroxyl compound decreased p21 expression [76] but inhibited growth and induced apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cell lines [15, 83]. DIM-C-pPhOH did not alter expression or location (nuclear) of NR4A1. Moreover, in transactivation assays using GAL4-NR4A1 (human)/GAL4-luc constructs in pancreatic cancer cells, DIM-C-pPhOH decreased luciferase in GAL4-receptor chimeras expressing wild-type receptor the truncated A/B domain, whereas the GAL4-NR4A1 (C–F domain) exhibited low activity and was not affected by treatment with DIM-C-pPhOH [15]. This contrasted to CsnB and related analogs that interact with the ligand binding domain of NR4A1 [49, 50]. These results suggest that DIM-C-pPhOH is more than an inhibitor (antagonist) of DIM-C-pPhOCH3-mediated activation of NR4A1 and appears to act as a deactivator of NR4A1 via the A/B domain of the receptor, and the specific sites of DIM-C-pPhOH-mediated deactivation of NR4A1 (A/B) domain are currently being investigated.

Since previous studies show that knockdown of NR4A1 by RNA interference or antisense oligonucleotides decreases growth and/or induces apoptosis in several cancer cell lines, if DIM-C-pPhOH truly inactivates NR4A1, then both siNR4A1 and DIM-C-pPhOH should exhibit comparable activities. Both DIM-C-pPhOH and siNR4A1 inhibit growth of multiple pancreatic cancer cell lines and induce apoptosis in these cells [15]. Moreover, DIM-C-pPhOH inhibits tumor growth and induces apoptosis in tumors in an orthotopic murine pancreatic tumor model. The growth inhibitory/pro-apoptotic effects of DIM-C-pPhOH and siNR4A1 in pancreatic cancer cells and tumors was accompanied by activation of caspase-3 and PARP cleavage and downregulation of the pro-survival genes survivin and bcl-2. Identification of a NR deactivator such as DIM-C-pPhOH is rare but not unprecedented among this family of transcriptions. The orphan receptor estrogen-related receptor (ERRα) also exhibits pro-oncogenic activity in breast cancer cells and small molecules that deactivate ERRα inhibit breast cancer cell and tumor growth [91–93].

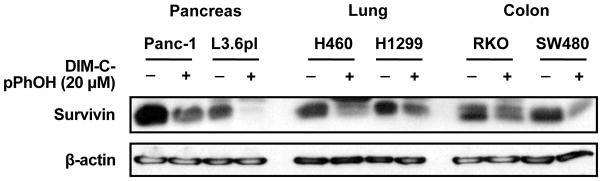

In pancreatic cancer cells, DIM-C-pPhOH decreased expression of survivin, and Figure 4 shows that this response is commonly observed in other cancer cell lines. Basal expression of survivin in cancer cell lines is complex and due to multiple transcription factors [94, 95]. RNA interference studies in this laboratory show that survivin is regulated in pancreatic and other cancer cells lines by Sp1, Sp3 and Sp4 [96, 97]. Although DIM-C-pPhOH downregulates survivin mRNA and protein expression and also decreases transactivation in cells transfected with GC-rich survivin constructs, these responses are not accompanied by downregulation of Sp transcription factors [15]. Further analysis of the mechanism of DIM-C-pPhOH-dependent downregulation of survivin showed that endogenous expression of survivin was dependent on an Sp1/NR4A1/p300 complex and results of chromatin immunoprecipitation assays showed that treatment with DIM-C-pPhOH resulted in loss of p300 from the complex which is bound to GC-rich sites. Thus, downregulation of survivin by DIM-C-pPhOH involved inactivation of NR4A1 which decreased binding to p300 and this was not accompanied by changes in NR4A1, p300 or Sp1 protein levels. The role of DIM-C-pPhOH-dependent deactivation of NR4A1 on other responses/genes in cancer cells and tumors is currently being investigated, and identification of other NR4A1 deactivators and their potential for clinical applications is also ongoing.

Figure 4.

Treatment of cancer cell lines with 15 μM DIM-C-pPhOH for 24 hr decreases expression of survivin protein as previously described in pancreatic cancer cells [15].

5. Summary

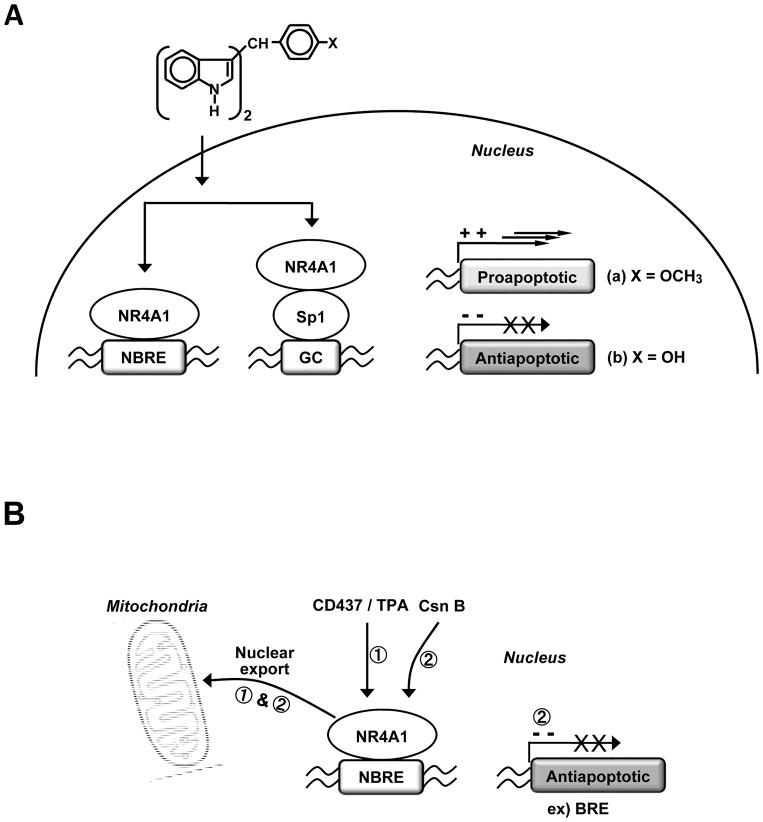

The orphan receptor NR4A1 is important in cellular homeostasis and ongoing studies in several laboratories clearly demonstrate that this receptor has an important role in carcinogenesis and is a novel target for cancer chemotherapy. In most cancer cells, NR4A1 is a pro-oncogenic factor involved in cell survival and growth. Many pro-apoptotic agents such as CD437 and TPA which do not bind NR4A1 induce receptor expression and nuclear export resulting in formation of a mitochondrial NR4A1-bcl-2 pro-apoptotic complex (Fig. 5). In contrast, cytosporone B and related compounds bind NR4A1 and activate apoptosis through both nuclear localization and nuclear export pathways. C-DIM compounds such as DIM-C-pPhOCH3 and DIM-C-pPhOH activate and deactivate nuclear NR4A1 to induce growth inhibition and apoptosis through different pathways. As illustrated in Figure 5, NR4A1 can be targeted by different mechanism-based anticancer drugs, suggesting several novel strategies for developing new analogs for cancer chemotherapy and for combination with radiotherapy and other drugs.

Figure 5.

Multiple pathways for nuclear export and activation/deactivation of NR4A1 to induce apoptosis in cancer cells.

6. Expert Opinion

NR4A1 is highly expressed in many tumors, and RNA interference studies suggest that this orphan receptor and perhaps all three NR4A receptors are pro-oncogenic factors. In order to use NR4A1 as a drug target, the tumor type-specific expression patterns and function of this receptor need to be more comprehensively investigated. NR4A1 is also an intriguing drug target because of its novel and diverse mechanisms of action which involve (i) drug-induced nuclear export that results in formation of a pro-apoptotic mitochondrial NR4A1-bcl-2 complex; (ii) drug-induced nuclear export that results in mitochondrial-independent apoptosis; (iii) ligand-dependent activation, and (iv) deactivation of nuclear NR4A1 leading to apoptosis and growth inhibition. It is critical to continue development of agents that activate individual and multiple pathways in order to assess their potential effectiveness as anticancer agents. Drug-induced activation of nuclear and extranuclear NR4A1-dependent pathways and the effectiveness of these agents may be tumor type-specific and this needs further investigation. Despite the gap in knowledge on NR4A1, in our opinion, this orphan receptor may be an important drug target for cancer chemotherapy.

Highlights.

NR4A receptors and particularly NR4A1 are important in carcinogenesis.

These orphan receptors are exciting and novel targets for development of new mechanism-based anticancer drugs.

These results clearly demonstrate important new concepts for inducing apoptosis in cancer cells in which NR4A1 mimics can be developed for future clinical applications.

These anticancer drugs (C-DIMs) act strictly through nuclear NR4A1 to induce apoptosis in cancer cells and tumors.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Gronemeyer H, Gustafsson JA, Laudet V. Principles for modulation of the nuclear receptor superfamily. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:950–964. doi: 10.1038/nrd1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKenna NJ, Cooney AJ, DeMayo FJ, et al. Minireview: Evolution of NURSA, the Nuclear Receptor Signaling Atlas. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:740–746. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benoit G, Cooney A, Giguere V, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. LXVI. Orphan nuclear receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:798–836. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bookout AL, Jeong Y, Downes M, et al. Anatomical profiling of nuclear receptor expression reveals a hierarchical transcriptional network. Cell. 2006;126:789–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi Y. Orphan nuclear receptors in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12:440–445. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paulsen RF, Granas K, Johnsen H, et al. Three related brain nuclear receptors, NGFI-B, Nurr1, and NOR-1, as transcriptional activators. J Mol Neurosci. 1995;6:249–255. doi: 10.1007/BF02736784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy EP, Dobson AD, Keller C, et al. Differential regulation of transcription by the NURR1/NUR77 subfamily of nuclear transcription factors. Gene Expr. 1996;5:169–179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saucedo-Cardenas O, Kardon R, Ediger TR, et al. Cloning and structural organization of the gene encoding the murine nuclear receptor transcription factor, NURR1. Gene. 1997;187:135–139. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00736-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maxwell MA, Muscat GE. The NR4A subgroup: immediate early response genes with pleiotropic physiological roles. Nucl Recept Signal. 2006;4:e002. doi: 10.1621/nrs.04002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pearen MA, Muscat GE. Minireview: Nuclear hormone receptor 4A signaling: implications for metabolic disease. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:1891–1903. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11*.Zhang XK. Targeting Nur77 translocation. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2007;11:69–79. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.1.69. Recent review summarizing Nur77/TR3 nuclear export. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho SD, Lee SO, Chintharlapalli S, et al. Activation of nerve growth factor-induced Bα by methylene-substituted diindolylmethanes in bladder cancer cells induces apoptosis and inhibits tumor growth. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77:396–404. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.061143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho SD, Yoon K, Chintharlapalli S, et al. Nur77 agonists induce proapoptotic genes and responses in colon cancer cells through nuclear receptor-dependent and independent pathways. Cancer Res. 2007;67:674–683. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu H, Lin Y, Li W, et al. Regulation of Nur77 expression by {beta}-catenin and its mitogenic effect in colon cancer cells. FASEB J. 2010 doi: 10.1096/fj.10-166462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15**.Lee SO, Abdelrahim M, Yoon K, et al. Inactivation of the orphan nuclear receptor TR3/Nur77 inhibits pancreatic cancer cell and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6824–6836. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1992. First identification of a deactivator of nuclear TR3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmes WF, Soprano DR, Soprano KJ. Comparison of the mechanism of induction of apoptosis in ovarian carcinoma cells by the conformationally restricted synthetic retinoids CD437 and 4-HPR. J Cell Biochem. 2003;89:262–278. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmes WF, Soprano DR, Soprano KJ. Early events in the induction of apoptosis in ovarian carcinoma cells by CD437: activation of the p38 MAP kinase signal pathway. Oncogene. 2003;22:6377–6386. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shin HJ, Lee BH, Yeo MG, et al. Induction of orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 gene expression and its role in cadmium-induced apoptosis in lung. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:1467–1475. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Q, Liu S, Ye XF, et al. Dual roles of Nur77 in selective regulation of apoptosis and cell cycle by TPA and ATRA in gastric cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1583–1592. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.10.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milbrandt J. Nerve growth factor induces a gene homologous to the glucocorticoid receptor gene. Neuron. 1988;1:183–188. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu Q, Dawson MI, Zheng Y, et al. Inhibition of trans-retinoic acid-resistant human breast cancer cell growth by retinoid X receptor-selective retinoids. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6598–6608. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li QX, Ke N, Sundaram R, et al. NR4A1, 2, 3--an orphan nuclear hormone receptor family involved in cell apoptosis and carcinogenesis. Histol Histopathol. 2006;21:533–540. doi: 10.14670/HH-21.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ke N, Claassen G, Yu DH, et al. Nuclear hormone receptor NR4A2 is involved in cell transformation and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8208–8212. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexopoulou AN, Leao M, Caballero OL, et al. Dissecting the transcriptional networks underlying breast cancer: NR4A1 reduces the migration of normal and breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R51. doi: 10.1186/bcr2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uemura H, Chang C. Antisense TR3 orphan receptor can increase prostate cancer cell viability with etoposide treatment. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2329–2334. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.5.5969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bras A, Albar JP, Leonardo E, et al. Ceramide-induced cell death is independent of the Fas/Fas ligand pathway and is prevented by Nur77 overexpression in A20 B cells. Cell Death Differ. 2000;7:262–271. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolluri SK, Bruey-Sedano N, Cao X, et al. Mitogenic effect of orphan receptor TR3 and its regulation by MEKK1 in lung cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8651–8667. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8651-8667.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeng H, Qin L, Zhao D, et al. Orphan nuclear receptor TR3/Nur77 regulates VEGF-A-induced angiogenesis through its transcriptional activity. J Exp Med. 2006;203:719–729. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Azoitei N, Pusapati GV, Kleger A, et al. Protein kinase D2 is a crucial regulator of tumour cell-endothelial cell communication in gastrointestinal tumours. Gut. 2010;59:1316–1330. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.206813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen GQ, Lin B, Dawson MI, et al. Nicotine modulates the effects of retinoids on growth inhibition and RAR beta expression in lung cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:171–178. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Q, Li Y, Liu R, et al. Modulation of retinoic acid sensitivity in lung cancer cells through dynamic balance of orphan receptors nur77 and COUP-TF and their heterodimerization. EMBO J. 1997;16:1656–1669. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramaswamy S, Ross KN, Lander ES, et al. A molecular signature of metastasis in primary solid tumors. Nat Genet. 2003;33:49–54. doi: 10.1038/ng1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao X, Liu W, Lin F, et al. Retinoid X receptor regulates Nur77/TR3-dependent apoptosis [corrected] by modulating its nuclear export and mitochondrial targeting. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9705–9725. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.9705-9725.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dawson MI, Hobbs PD, Peterson VJ, et al. Apoptosis induction in cancer cells by a novel analogue of 6-[3-(1-adamantyl)-4-hydroxyphenyl]-2-naphthalenecarboxylic acid lacking retinoid receptor transcriptional activation activity. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4723–4730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35**.Li H, Kolluri SK, Gu J, et al. Cytochrome c release and apoptosis induced by mitochondrial targeting of nuclear orphan receptor TR3. Science. 2000;289:1159–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1159. Detailed molecular description on drug-induced nuclear export of TR3 and mitochondrial targeting. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Y, Lin B, Agadir A, et al. Molecular determinants of AHPN (CD437)-induced growth arrest and apoptosis in human lung cancer cell lines. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4719–4731. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37**.Lin B, Kolluri SK, Lin F, et al. Conversion of Bcl-2 from protector to killer by interaction with nuclear orphan receptor Nur77/TR3. Cell. 2004;116:527–540. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00162-x. Detailed molecular description on drug-induced nuclear export of TR3 and mitochondrial targeting. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kolluri SK, Zhu X, Zhou X, et al. A short Nur77-derived peptide converts Bcl-2 from a protector to a killer. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:285–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferlini C, Cicchillitti L, Raspaglio G, et al. Paclitaxel directly binds to Bcl-2 and functionally mimics activity of Nur77. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6906–6914. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jeong JH, Park JS, Moon B, et al. Orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 translocates to mitochondria in the early phase of apoptosis induced by synthetic chenodeoxycholic acid derivatives in human stomach cancer cell line SNU-1. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1010:171–177. doi: 10.1196/annals.1299.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson AJ, Arango D, Mariadason JM, et al. TR3/Nur77 in colon cancer cell apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5401–5407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee JM, Lee KH, Weidner M, et al. Epstein-Barr virus EBNA2 blocks Nur77- mediated apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11878–11883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182552499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee JM, Lee KH, Farrell CJ, et al. EBNA2 is required for protection of latently Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells against specific apoptotic stimuli. J Virol. 2004;78:12694–12697. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12694-12697.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee KW, Ma L, Yan X, et al. Rapid apoptosis induction by IGFBP-3 involves an insulin-like growth factor-independent nucleomitochondrial translocation of RXRα/Nur77. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16942–16948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412757200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gennari A, Bleumink R, Viviani B, et al. Identification by DNA macroarray of nur77 as a gene induced by di-n-butyltin dichloride: its role in organotin-induced apoptosis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2002;181:27–31. doi: 10.1006/taap.2002.9357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chinnaiyan P, Varambally S, Tomlins SA, et al. Enhancing the antitumor activity of ErbB blockade with histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1041–1050. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen YL, Jian MH, Lin CC, et al. The induction of orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 expression by n-butylenephthalide as pharmaceuticals on hepatocellular carcinoma cell therapy. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1046–1058. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.044800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu J, Zhou W, Li SS, et al. Modulation of orphan nuclear receptor Nur77-mediated apoptotic pathway by acetylshikonin and analogues. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8871–8880. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49**.Liu JJ, Zeng HN, Zhang LR, et al. A unique pharmacophore for activation of the nuclear orphan receptor Nur77 in vivo and in vitro. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3628–3637. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3160. New ligands that bind and activate TR3/Nur77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50**.Zhan Y, Du X, Chen H, et al. Cytosporone B is an agonist for nuclear orphan receptor Nur77. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:548–556. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.106. New ligands that bind and activate TR3/Nur77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin XF, Zhao BX, Chen HZ, et al. RXRalpha acts as a carrier for TR3 nuclear export in a 9-cis retinoic acid-dependent manner in gastric cancer cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5609–5621. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Katagiri Y, Takeda K, Yu ZX, et al. Modulation of retinoid signalling through NGF-induced nuclear export of NGFI-B. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:435–440. doi: 10.1038/35017072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Han YH, Cao X, Lin B, et al. Regulation of Nur77 nuclear export by c-Jun N-terminal kinase and Akt. Oncogene. 2006;25:2974–2986. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen HZ, Zhao BX, Zhao WX, et al. Akt phosphorylates the TR3 orphan receptor and blocks its targeting to the mitochondria. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:2078–2088. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang H, Bushue N, Bu P, et al. Induction and intracellular localization of Nur77 dictate fenretinide-induced apoptosis of human liver cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:948–954. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen L, Hu L, Chan TH, et al. Chromodomain helicase/adenosine triphosphatase DNA binding protein 1-like (CHD1l) gene suppresses the nucleus-to-mitochondria translocation of nur77 to sustain hepatocellular carcinoma cell survival. Hepatology. 2009;50:122–129. doi: 10.1002/hep.22933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen L, Yuan YF, Li Y, et al. Clinical significance of CHD1L in hepatocellular carcinoma and therapeutic potentials of virus-mediated CHD1L depletion. Gut. 2010 doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Safe S, Papineni S, Chintharlapalli S. Cancer chemotherapy with indole-3-carbinol, bis(3′-indolyl)methane and synthetic analogs. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:326–338. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aggarwal BB, Ichikawa H. Molecular targets and anticancer potential of indole-3-carbinol and its derivatives. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1201–1215. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.9.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Le HT, Schaldach CM, Firestone GL, et al. Plant-derived 3,3′-diindolylmethane is a strong androgen antagonist in human prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21136–21145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300588200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shilling AD, Carlson DB, Katchamart S, et al. 3,3′-diindolylmethane, a major condensation product of indole-3-carbinol, is a potent estrogen in the rainbow trout. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2001;170:191–200. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.9100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen I, Safe S, Bjeldanes L. Indole-3-carbinol and diindolylmethane as aryl hydrocarbon (Ah) receptor agonists and antagonists in T47D human breast cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;51:1069–1076. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen I, McDougal A, Wang F, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated antiestrogenic and antitumorigenic activity of diindolylmethane. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:1631–1639. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.9.1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bjeldanes LF, Kim JY, Grose KR, et al. Aromatic hydrocarbon responsiveness-receptor agonists generated from indole-3-carbinol in vitro and in vivo - comparisons with 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:9543–9547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Qin C, Morrow D, Stewart J, et al. A new class of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) agonists that inhibit growth of breast cancer cells: 1,1-bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-substitutedphenyl)methanes. Mol Cancer Therap. 2004;3:247–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chintharlapalli S, Smith R, III, Samudio I, et al. 1,1-Bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-substitutedphenyl)methanes induce peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ mediated growth inhibition, transactivation and differentiation markers in colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5994–6001. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hong J, Samudio I, Liu S, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ dependent activation of p21 in Panc-28 pancreatic cancer cells involves Sp1 and Sp4 proteins. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5774–5785. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chintharlapalli S, Papineni S, Baek SJ, et al. 1,1-Bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-substitutedphenyl)methanes are peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists but decrease HCT-116 colon cancer cell survival through receptor-independent activation of early growth response-1 and NAG-1. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:1782–1792. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.017046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kassouf W, Chintharlapalli S, Abdelrahim M, et al. Inhibition of bladder tumor growth by 1,1-bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-substitutedphenyl)methanes: a new class of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ agonists. Cancer Res. 2006;66:412–418. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chintharlapalli S, Papineni S, Safe S. 1,1-Bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-substituted phenyl)methanes inhibit colon cancer cell and tumor growth through PPARγ-dependent and PPARγ-independent pathways. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1362–1370. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chintharlapalli S, Papineni S, Safe S. 1,1-Bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-substitutedphenyl)methanes inhibit growth, induce apoptosis, and decrease the androgen receptor in LNCaP prostate cancer cells through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ-independent pathways. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:558–569. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.028696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Su Y, Vanderlaag K, Ireland C, et al. 1,1-Bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-biphenyl)methane inhibits basal-like breast cancer growth in athymic nude mice. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R56. doi: 10.1186/bcr1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.York M, Abdelrahim M, Chintharlapalli S, et al. 1,1-Bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-substitutedphenyl)methanes induce apoptosis and inhibit renal cell carcinoma growth. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6743–6752. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vanderlaag K, Su Y, Frankel AE, et al. 1,1-Bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-substituted phenyl)methanes inhibit proliferation of estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer cells by activation of multiple pathways. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;109:273–283. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9648-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ichite N, Chougule MB, Jackson T, et al. Enhancement of docetaxel anticancer activity by a novel diindolylmethane compound in human non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:543–552. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guo J, Chintharlapalli S, Lee SO, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-dependent activity of indole ring-substituted 1,1-bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-biphenyl)methanes in cancer cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;66:141–150. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1144-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lei P, Abdelrahim M, Safe S. 1,1-Bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-substituted phenyl)methanes inhibit ovarian cancer cell growth through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-dependent and independent pathways. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2324–2336. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lei P, Abdelrahim M, Cho SD, et al. 1,1-Bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-substituted phenyl)methanes inhibit colon cancer cell and tumor growth through activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1139–1147. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lei P, Abdelrahim M, Cho SD, et al. Structure-dependent activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis in pancreatic cancer by 1,1-bis(3′-indoly)-1-(p-substituted phenyl)methanes. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3363–3372. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Abdelrahim M, Newman K, Vanderlaag K, et al. 3,3′-Diindolylmethane (DIM) and derivatives induce apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells through endoplasmic reticulum stress-dependent upregulation of DR5. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:717–728. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Contractor R, Samudio I, Estrov Z, et al. A novel ring-substituted diindolylmethane 1,1-bis[3′-(5-methoxyindolyl)]-1-(p-t-butylphenyl)methane inhibits ERK activation and induces apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2890–2898. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sohn YC, Kwak E, Na Y, et al. Silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors and activating signal cointegrator-2 as transcriptional coregulators of the orphan nuclear receptor Nur77. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43734–43739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chintharlapalli S, Burghardt R, Papineni S, et al. Activation of Nur77 by selected 1,1-Bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-substituted phenyl)methanes induces apoptosis through nuclear pathways. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24903–24914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Maira M, Martens C, Batsche E, et al. Dimer-specific potentiation of NGFI-B (Nur77) transcriptional activity by the protein kinase A pathway and AF-1-dependent coactivator recruitment. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:763–776. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.3.763-776.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Philips A, Lesage S, Gingras R, et al. Novel dimeric Nur77 signaling mechanism in endocrine and lymphoid cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5946–5951. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.5946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cho SD, Lei P, Abdelrahim M, et al. 1,1-Bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-methoxyphenyl)methane activates Nur77-independent proapoptotic responses in colon cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2008;47:252–263. doi: 10.1002/mc.20378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lee SO, Chintharlapalli S, Liu S, et al. p21 Expression is induced by activation of nuclear nerve growth factor-induced Bα (NGFI-Bα, Nur77) in pancreatic cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:1169–1178. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liu M, Iavarone A, Freedman LP. Transcriptional activation of the human p21(WAF1/CIP1) gene by retinoic acid receptor. Correlation with retinoid induction of U937 cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31723–31728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Owen GI, Richer JK, Tung L, et al. Progesterone regulates transcription of the p21WAF1 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor gene through Sp1 and CBP/p300. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10696–10701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lu S, Jenster G, Epner DE. Androgen induction of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 gene: role of androgen receptor and transcription factor Sp1 complex. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:753–760. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.5.0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stein RA, Gaillard S, McDonnell DP. Estrogen-related receptor alpha induces the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in breast cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;114:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Stein RA, Chang CY, Kazmin DA, et al. Estrogen-related receptor alpha is critical for the growth of estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8805–8812. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chisamore MJ, Wilkinson HA, Flores O, et al. Estrogen-related receptor-alpha antagonist inhibits both estrogen receptor-positive and estrogen receptor-negative breast tumor growth in mouse xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:672–681. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pennati M, Folini M, Zaffaroni N. Targeting survivin in cancer therapy: fulfilled promises and open questions. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1133–1139. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Stauber RH, Mann W, Knauer SK. Nuclear and cytoplasmic survivin: molecular mechanism, prognostic, and therapeutic potential. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5999–6002. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chadalapaka G, Jutooru I, Chintharlapalli S, et al. Curcumin decreases specificity protein expression in bladder cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5345–5354. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jutooru I, Chadalapaka G, Lei P, et al. Inhibition of NFκB and pancreatic cancer cell and tumor growth by curcumin is dependent on specificity protein downregulation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:25332–25344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.095240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]