Abstract

Rationale: Children who are young, malnourished, and infected with HIV have significant risk of tuberculosis (TB) morbidity and mortality following TB infection. Treatment of TB infection is hindered by poor detection and limited pediatric data.

Objectives: Identify improved testing to detect pediatric TB infection.

Methods: This was a prospective community-based study assessing use of the tuberculin skin test and IFN-γ release assays among children (n = 1,343; 6 mo to <15 yr) in TB-HIV high-burden settings; associations with child characteristics were measured.

Measurements and Main Results: Contact tracing detects TB in 8% of child contacts within 3 months of exposure. Among children with no documented contact, tuberculin skin test and QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube positivity was greater than T-SPOT.TB. Nearly 8% of children had IFN-γ release assay positive and skin test negative discordance. In a model accounting for confounders, all tests correlate with TB contact, but IFN-γ release assays correlate better than the tuberculin skin test (P = 0.0011). Indeterminate IFN-γ release assay results were not associated with age. Indeterminate QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube results were more frequent in children infected with HIV (4.7%) than uninfected with HIV (1.9%), whereas T-SPOT.TB indeterminates were rare (0.2%) and not affected by HIV status. Conversion and reversion were not associated with HIV status. Among children infected with HIV, tests correlated less with contact as malnutrition worsened.

Conclusions: Where resources allow, use of IFN-γ release assays should be considered in children who are young, recently exposed, and infected with HIV because they may offer advantages compared with the tuberculin skin test for identifying TB infection, and improve targeted, cost-effective delivery of preventive therapy. Affordable tests of infection could dramatically impact global TB control.

Keywords: HIV, latent tuberculosis infection, pediatrics, IFN-γ release tests, tuberculin test

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Treating latent tuberculosis infection prevents tuberculosis disease. Improved detection of infection in children could increase the cost-effectiveness of postexposure preventive treatment.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Contact tracing detects tuberculosis in nearly 8% of child contacts within 3 months of exposure. In a model accounting for confounders, all tests correlate with tuberculosis contact, but IFN-γ release assays correlate better than the tuberculin skin test (P = 0.0011). The frequency of IFN-γ release assay indeterminate results did not differ in younger compared with older children. Among children infected with HIV, the correlation between tuberculosis contact and all tests of infection declines as malnutrition worsens. Resources permitting, the use of IFN-γ release assays should be considered in children who are young, recently exposed, and infected with HIV.

Following infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the 5-year risk of tuberculosis (TB) is 33% in children younger than 5 years and 20% for 5–14 years of age (1). TB risk is greatest in the year following infection and highest among young, malnourished, and immune-compromised children; up to 50% of children infected during the first year of life develop disease in the absence of preventive therapy (PT) (2). PT decreases TB morbidity and mortality among adult contacts (3, 4) and markedly reduces TB risk in child contacts (5, 6). Nevertheless, in 2010, of 7.6 million children infected with M. tuberculosis, more than 650,000 developed TB (7), and 74,000 children not infected with HIV died of TB (8).

In low-burden countries, most TB occurs in foreign-born persons (9), making screening, diagnosing, and treating latent TB infection (LTBI) at immigration a cost-effective control strategy (10); diagnosis of M. tuberculosis infection guides LTBI treatment. In high-burden settings, guidelines recommend PT based on TB exposure history, with proof of infection not mandatory (11).

In young children with highest risk of TB, bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination limits tuberculin skin test (TST) specificity and consequent targeted delivery of PT. IFN-γ release assays (IGRAs) are more specific tests quantifying the in vitro production of IFN-γ by T cells after ex vivo stimulation with M. tuberculosis–specific antigens (12). In children, the estimated specificity for LTBI is 94, 91, and 88% for the ELISPOT-based test, ELISA-based test, and TST, respectively (13). Systematic reviews in children failed to identify a superior test of infection (13, 14), but suggest that host factors affect test performance (13).

Programmatic TB screening guidelines vary considerably (15). U.S. guidelines preferentially recommend IGRAs in BCG-vaccinated individuals, whereas the TST is preferred in young children because data on IGRAs are limited (16). U.S. guidelines further recommend IGRA in conjunction with TST to improve sensitivity in high-risk populations including young and HIV-infected persons. The UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines recommend stepwise IGRA use in TST-positive individuals (17). In contrast, the World Health Organization (WHO) does not recommend IGRAs for high-burden settings (18), in the absence of data on benefit. Additional data regarding IGRA sensitivity in children could inform current guidelines.

We assessed the use of the TST and commercial IGRAs for the detection of M. tuberculosis infection in children living in a TB-HIV high-burden setting while measuring associations between test outcome and host characteristics.

Methods

Study Setting and Design

We conducted a prospective, household-contact study in Cape Town, Western Cape Province, South Africa, of children recently exposed to a TB source case identified at community TB clinics, and children with documented recent TB exposure from routine outpatient care. Children with no documented TB exposure were recruited from neighboring households and outpatient care to measure background community exposure. BCG coverage (single vaccination at birth; Danish strain, intradermal) is greater than 98% (19).

Eligibility

Children infected and uninfected with HIV aged 3 months to 15 years with and without documented TB exposure were eligible. Children with documented TB exposure were recruited within 3 months of the source case starting treatment. Weight less than 5 kg, hemoglobin less than 9 g/dl, and current TB treatment were exclusion criteria. Enrollment was deferred in the presence of TST (preceding 12 wk); live attenuated vaccination (preceding 6 wk); or acute severe respiratory, diarrheal, or neurologic illness.

Study Measures

Data on age, ethnicity, BCG vaccination (scar and written history), household death (preceding year), passing a worm (preceding 3 mo), and previous TB exposure or disease were collected from parents and caregivers and data verified from TB registers. Source case sputum specimens underwent smear and culture.

We used well-quantified TB exposure as a surrogate measure of M. tuberculosis infection (20). Pediatric-specific exposure data from a subset of children negative for HIV with documented TB exposure were used to derive a contact score (range, 0–10) assigning a higher value as exposure intensity increases (20). Additional detail on these methods is provided in the online supplement.

HIV testing and counseling was completed on children with unknown or negative status (Abbott Determine HIV-1/2 rapid test). Positive or indeterminate HIV rapid tests were confirmed with ELISA (children >18 mo) or DNA polymerase chain reaction (children ≤18 mo). Children infected with HIV had access to combination antiretroviral therapy (cART).

Children completed three tests to assess M. tuberculosis infection status, at enrolment and 3 months. TST (two Tuberculin Units RT-23; Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark) was placed and read by study nurses (who completed repeat standardization training) 48–72 hours after administration. Children with history of TST ulceration did not complete TST. IGRAs were completed following manufacturers’ guidelines: QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT; Cellestis Limited, Carnegie, Victoria, Australia) and T-SPOT.TB (TSpot; Oxford Immunotec, Oxford, UK). IGRA samples were obtained immediately before TST and transported to the research laboratory within 3 hours. Because of funding limitations, children older than 5 years of age recruited from two entry points did not complete TSpot. Laboratory and clinical teams were masked to clinical data and IGRA results, respectively.

Children were screened for TB through standardized symptom screening (21), chest radiography (anteroposterior and lateral), and mycobacterial culture (MGIT; Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) of gastric aspirates or sputum. Two masked independent experts read chest radiographs, using a standardized pediatric tool (22). If discordant, a third masked reviewer’s classification was used. Standard weight and height measurements were completed. Additional detail regarding TB evaluation and the protocol-specific TB case definition are provided in the online supplement.

Children younger than 6 years and children infected with HIV with a positive TST or documented TB exposure were referred for 6-month PT (isoniazid, 10–15 mg/kg/d); children diagnosed with TB were referred for 6-month directly observed treatment.

The research ethics committees of Baylor College of Medicine, Stellenbosch University, Case Western Reserve University, and local health authorities approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all parents and caregivers; children older than 7 years gave assent. Standards for studies of diagnostic accuracy were followed (23).

Statistical Analysis

The TST was coded positive if greater than or equal to 10 mm in children uninfected with HIV and greater than or equal to 5 mm in children infected with HIV. IGRAs were interpreted following manufacturers’ guidelines. Indeterminate results were recorded and excluded from analysis. Operational challenges recorded included failed phlebotomy, laboratory error, and insufficient specimen. To capture children with test conversions, M. tuberculosis infection status was also defined by a composite measure defining a child as infected by a specific test if positive at either baseline or 3 months. The proportion of positive results was compared across tests using McNemar chi-square test.

Comparisons between children infected and uninfected with HIV were performed using Pearson chi-square and the Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Agreement between tests was assessed using the κ statistic (24). The association between covariates and each test was assessed using logistic regression while controlling for M. tuberculosis exposure (20). Models with common variables and interaction terms were developed to support simultaneous comparison of the index tests. Interactions with HIV status were considered and retained if P less than 0.05. Final models were also run in subgroups stratified by age and subgroups excluding children diagnosed with TB within 3 months of enrollment. To estimate and compare contact score association across index tests a generalized estimating equation model (25, 26) was fitted, treating tests as the multivariate dependent variable. A covariate was included to distinguish between tests and was interacted with the contact score. An assessment was performed to understand if any differences were found between children with complete or missing TST or IGRA results at baseline and 3-month visit. Because no significant differences were found, no adjustment for missing data was considered. Analyses used Stata v10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) and SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Characteristics of Study Population

Between January 2008 and July 2012, a total of 1,343 children (median age, 59 mo; interquartile range [IQR], 27–103 mo) were enrolled including 836 with documented TB exposure and 507 without documented TB exposure. A total of 912 children were recruited from the community and 431 from the hospital outpatient department. A total of 22% (299 of 1,343) were infected with HIV; 169 from community and 130 from hospital-based antiretroviral clinics. Children infected with HIV were more likely of black race, stunted, to have acute malnutrition, and report past TB treatment, but less likely to have documented TB exposure in the past 3 months. Children infected with HIV had a median CD4 count of 1,317 per microliter (IQR, 867–1,804), CD4% of 30 (IQR, 23–36), and viral load of 1,882 copies per milliliter (IQR, 140–20,176); 88% were receiving cART (median, 22 mo; IQR, 9–43 mo) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Children Infected and Uninfected with HIV (n = 1,343)

| All Children (n = 1,343) [Median (IQR) or n/N (%)] | Children Infected with HIV (n = 299) [Median (IQR) or n/N (%)] | Children Uninfected with HIV (n = 1,044) [Median (IQR) or n/N (%)] | P Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mo | 58.6 (27.3 to 102.7) | 46.4 (25.0 to 72.8) | 61.8 (29.0 to 108.5) | <0.0001 |

| Male | 645/1,343 (48) | 152/299 (51) | 493/1,044 (47) | 0.2701 |

| Race | ||||

| African/black | 451/1,343 (34) | 220/299 (74) | 231/1,044 (22) | |

| Mixed-race | 887/1,343 (66) | 78/299 (26) | 809/1,044 (78) | <0.0001 |

| Indian/Asian/white | 5/1,343 (0.4) | 1/299 (0.3) | 4/1,044 (0.4) | |

| Height–age z score | −1.57 (−2.31 to −0.81) | −1.94 (−2.77 to −1.18) | −1.46 (−2.19 to −0.70) | <0.0001 |

| Weight–height z score | 0.51 (−0.22 to 1.27) | 0.68 (−0.02 to 1.47) | 0.45 (−0.31 to 1.14) | 0.0002 |

| Reported recent worm infection | 84/1,340 (6) | 23/298 (8) | 61/1,042 (6) | 0.2775 |

| Prior TB treatment | 162/1,340 (12) | 113/297 (38) | 49/1,043 (5) | <0.0001 |

| BCG vaccination† | 1,165/1,343 (87) | 261/299 (87) | 904/1,044 (87) | 0.7526 |

| cART at enrollment‡ | 251/289 (88) | |||

| CD4 count | 1,317 (867 to 1,804) | |||

| CD4 percentage | 30 (23 to 36) | |||

| Viral load§ | 1,882 (140 to 20,176) | |||

| Current TB contact | 836/1,340 (62) | 54/298 (18) | 782/1,042 (75) | <0.0001 |

| TB contact scoreǁ | 3 (0 to 5) | 0 (0 to 0) | 4 (0 to 6) | <0.0001 |

| TB contact score¶ | 5 (4 to 7) | 4 (2 to 6) | 5 (4 to 7) | 0.0051 |

| Recent household death | 118/1,338 (9) | 26/298 (9) | 92/1,040 (9) | 1.0000 |

Definition of abbreviations: BCG = bacillus Calmette-Guérin; cART = combination antiretroviral treatment; IQR = interquartile range; TB = tuberculosis.

Represents comparison of proportions (chi-square test) or medians (Wilcoxon rank-sum test) between children infected and not infected with HIV.

Children were considered BCG vaccinated if a BCG scar was noted or a record of vaccination was available.

Among the 38 children infected with HIV not receiving cART at baseline, five had started cART by the 3-month follow-up.

Viral load was lower than detectable limits in 126 children and missing in 31 children. Hence, the median and IQR were calculated in 142 children with detectable viral load values.

Calculated among all children.

Calculated only in children with a current TB contact.

Six percent (85 of 1,343) of children were diagnosed with TB within 3 months following enrollment (1). Of these, 76% (65 of 85) were diagnosed within 6 weeks; the sensitivity of the TST (75%), TSpot (71%), and QFT (79%) were similar. Test sensitivity increased if two tests were considered: TST/TSpot (83%), TST/QFT (84%), and TSpot/QFT (88%). Initial test sensitivity was lower among children diagnosed with TB greater than 6 weeks following enrollment: TST (48%), TSpot (37%), and QFT (47%).

Summary of Test Results, Agreement, and Concordance in Univariate Analyses

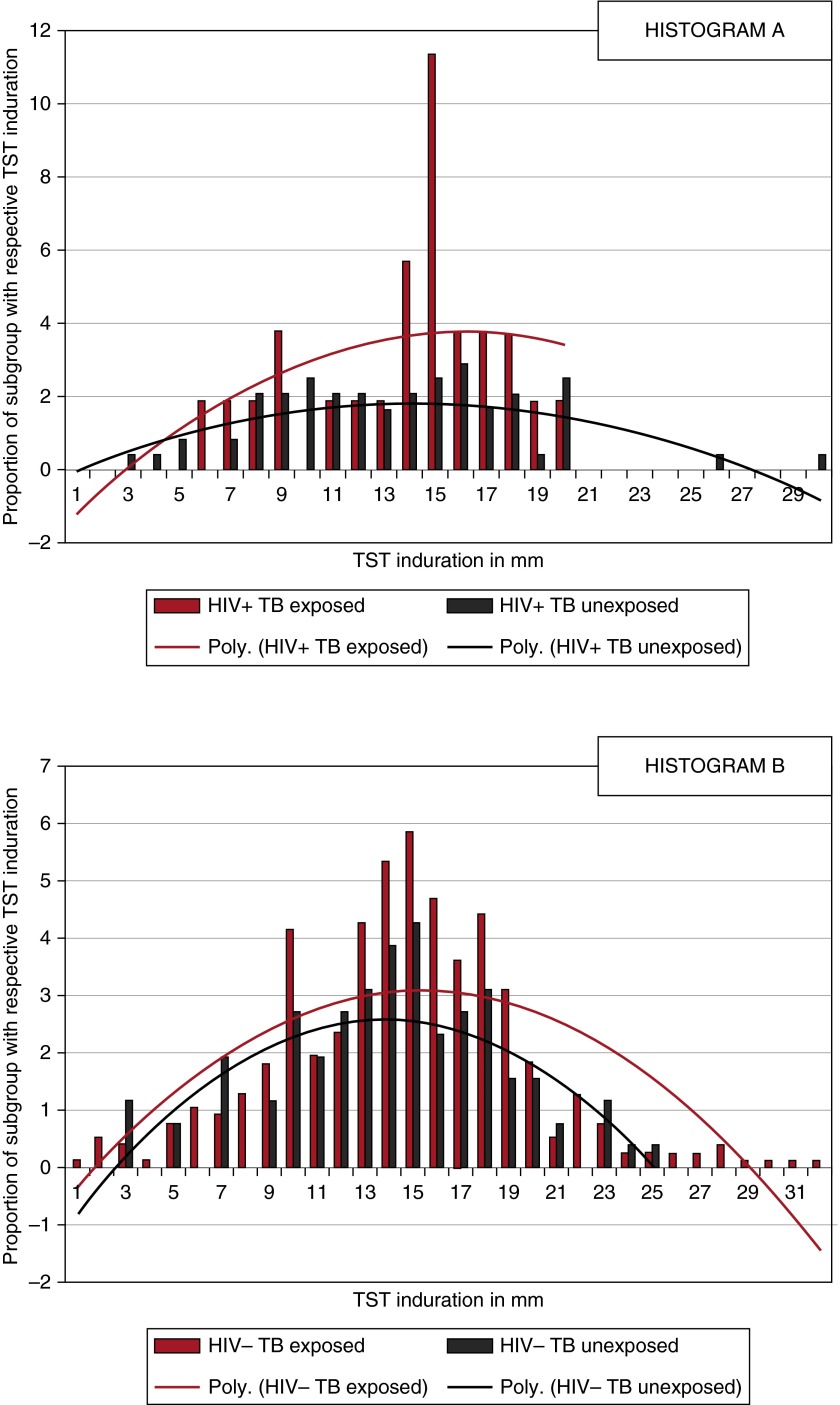

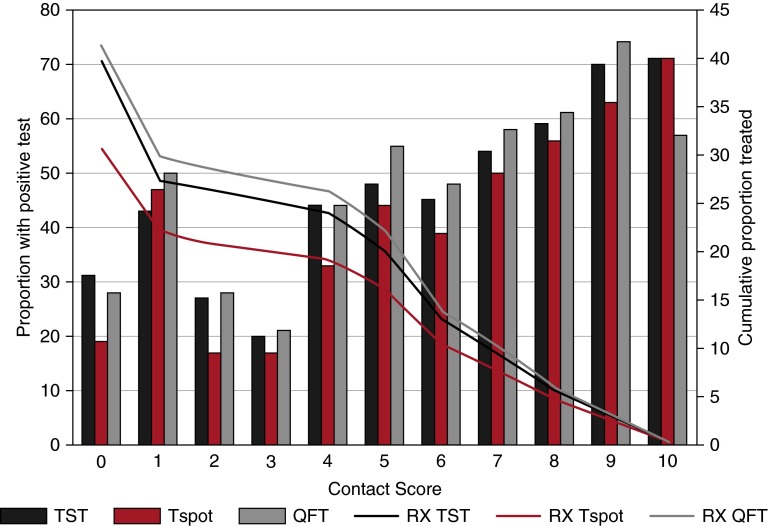

All baseline tests and composite measure of infection were more likely positive in children not infected with HIV (Table 2). TST distribution varied by HIV and TB exposure status (Figure 1). Positivity of all tests varied along the contact score continuum and would therefore result in differences in targeted treatment (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Measures of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection in Children Infected and Uninfected with HIV

| All Children (n = 1,343) [Median (IQR) or n/N (%)] | Children Infected with HIV (n = 299) [Median (IQR) or n/N (%)] | Children Uninfected with HIV (n = 1,044) [Median (IQR) or n/N (%)] | P Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TST, mm† | 14.5 (11.0–17.3) | 13.8 (10.0–16.3) | 14.6 (11.5–17.5) | 0.0390 |

| Baseline TST | ||||

| Positive‡ | 529/1,325 (39.9) | 93/295 (31.5) | 436/1,030 (42.3) | 0.0008§ |

| Missing|| | 18 | 4 | 14 | |

| Follow-up TST¶ | ||||

| Conversions | 71/645 (11.0) | 13/157 (8.3) | 58/488 (11.9) | 0.2094 |

| Reversions | 58/391 (14.8) | 11/62 (17.7) | 47/329 (14.3) | 0.4825 |

| TST composite** | 603/1,332 (45.3) | 107/296 (36.2) | 496/1,036 (47.8) | 0.0004 |

| Baseline QFT | ||||

| Positive | 520/1,261 (41.2) | 59/271 (21.8) | 461/990 (46.6) | <0.0001§ |

| Indeterminate | 34/1,343 (2.5) | 14/299 (4.7) | 20/1,044 (1.9) | 0.0114 |

| Insufficient volume | 4/1,343 (0.3) | 0/299 (0) | 4/1,044 (0.4) | 0.5810 |

| Failed runs/error | 8/1,343 (0.6) | 3/299 (1.0) | 5/1,044 (0.5) | 0.3870 |

| Missing†† | 36/1,343 (2.7) | 11/299 (3.7) | 25/1,044 (2.4) | 0.2259 |

| Follow-up QFT‡‡ | ||||

| Conversions | 55/602 (9.1) | 11/180 (6.1) | 44/422 (10.4) | 0.0925 |

| Reversions | 32/387 (8.3) | 6/47 (12.8) | 26/340 (7.6) | 0.2323 |

| QFT composite** | 591/1,318 (44.8) | 73/293 (24.9) | 518/1,025 (50.5) | <0.0001 |

| TSpot sample size | n = 1,093§§ | n = 297 | n = 796 | |

| Baseline TSpot | ||||

| Positive | 302/991 (30.5) | 39/263 (14.8) | 263/728 (36.1) | <0.0001§ |

| Indeterminate | 2/1,093 (0.2) | 1/297 (0.3) | 1/796 (0.1) | 0.4698 |

| Insufficient volume | 13/1,093 (1.2) | 4/297 (1.4) | 9/796 (1.1) | 0.7580 |

| Failed runs/error | 27/1,093 (2.5) | 9/297 (3.0) | 18/796 (2.3) | 0.5114 |

| Missing†† | 60/1,093 (5.5) | 20/297 (6.7) | 40/796 (5.0) | 0.2960 |

| Follow-up TSpot|||| | ||||

| Conversions | 61/576 (10.6) | 18/178 (10.1) | 43/398 (10.8) | 0.5173 |

| Reversions | 27/255 (10.6) | 3/30 (10.0) | 24/225 (10.7) | 0.0730 |

| TSpot composite** | 377/1,057 (35.7) | 59/290 (20.3) | 318/767 (41.5) | <0.0001 |

Definition of abbreviations: IQR = interquartile range; QFT = QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube; TSpot = T-SPOT.TB; TST = tuberculin skin test.

Represents comparison of proportions (chi-square) or medians (Wilcoxon rank-sum) between participants infected and uninfected with HIV.

Data only used if TST is greater than 0 mm.

TST greater than or equal to 10 mm were considered as positive for participants uninfected with HIV and TST greater than or equal to 5 mm for participants infected with HIV.

Statistical test is comparing positive and negative index test results.

Reasons for missing baseline TST include two TSTs read but result not recorded; three TSTs deferred because of history of extensive blistering following prior TST; one family refused because child had been previously treated for TB; one TST placed but did not return for reading; and 11 subjects with missing data.

Follow-up TST result not available in 158 children: 96 did not complete testing because of current tuberculosis treatment (47), refusal of parent or child (20), recent receipt of live vaccination (two), prior TST ulceration (12), and withdrawal from study because of relocation (24). Data are missing for 53 children.

M. tuberculosis infection status defined considering both baseline and 3-month test results. A child was defined as infected by a specific test if positive at either baseline or 3 months.

Blood was taken according to source documents, but samples were not logged or received at laboratory.

Follow-up QFT results were not available in 162 children because of the following reasons: indeterminate (eight), insufficient blood volumes (two), failed runs/laboratory error (21), refusal to provide a sample at the 3-month visit (36), withdrawal from study because of relocation (24), and missing data (71).

Because of funding limitations, children older than 5 years of age recruited from two entry points did not complete TSpot testing. Hence, the TSpot sample size is reduced compared with that of TST and QFT.

Follow-up TSpot results were not available in 150 children because of the following reasons: indeterminate (11), insufficient blood volumes (five), failed runs/laboratory error (53), refusal to provide a blood sample at the 3-month visit (23), withdrawal from the study because of relocation (20), and missing data (38).

Figure 1.

Tuberculin skin test (TST) distribution stratified by HIV status and tuberculosis (TB) exposure. (A) Data from TB-exposed (red bars) and TB-unexposed (black bars) children infected with HIV and two normalized lines for recent contacts (red line) and nonexposed control subjects (black line). (B) Data from TB-exposed (red bars) and TB-unexposed (black bars) children not infected with HIV and two normalized lines for recent contacts (red line) and nonexposed control subjects (black line). The normalized lines are derived using polynomial (Poly.) expressions because this fits our bell-shaped curve data best. Nonresponsive children were excluded from the histogram but varied by HIV and exposure status: HIV-infected and TB-exposed (53%); HIV-infected and no documented TB exposure (70%); HIV-uninfected and TB-exposed (47%); HIV-uninfected and no documented TB exposure (62%).

Figure 2.

Test positivity and treatment implications in relationship to contact score. Bars represent the proportion of children with respective positives test results along the continuum of exposure ranging from no known exposure (contact score = 0) to the highest level of exposure (contact score = 10). Lines demonstrate the cumulative proportion of children that would be offered IPT based on test positivity if contact score were considered a cut-point for IPT eligibility. If testing were used to guide IPT among children with a contact score greater than or equal to 2, TST, Tspot, and QFT would result in 26, 21, and 29% of children being offered treatment, respectively. In contrast, if testing were used to guide IPT among children with a contact score of greater than or equal to 5, TST, Tspot, and QFT would result in 20, 16, and 22% of children being offered treatment. Finally, if testing were used to guide IPT among children with a contact score greater than or equal than 10, no child would be treated because the highest contact score possible is 10. IPT = isoniazid preventive therapy; QFT = QuantiFERON; RX QFT = treatment guided by QFT response; RX Tspot = treatment guided by Tspot response; RX TST = treatment guided by TST response; Tspot = T-Spot.TB; TST = tuberculin skin test.

Indeterminate QFT results were more frequent in children infected (4.7%) than children not infected with HIV (1.9%), whereas TSpot indeterminate results were rare (0.2%) and did not vary by HIV status. Test conversion, reversion, and other operational measures were not associated with HIV status, age, or nutritional status. Conversions were common among children diagnosed with TB following enrollment: TST (14.2%), TSpot (27.2%), and QFT (14.2%).

Children who were older, uninfected with HIV, or TB exposed were more likely to have positive results for each test (see Tables E1–E3 in the online supplement). Children with negative TST or QFT results were more likely to be BCG-vaccinated than children with positive results. Acute malnutrition was associated with negative QFT and TSpot (P = 0.010 and 0.010, respectively), but not TST (P = 0.052). Children with a recent household death or who were receiving PT at the 3-month follow-up were more likely to have a positive TST (see Tables E1–E3); the latter reflecting TST positivity being an indication for referral.

Test agreement ranged from 0.71 to 0.78 in children not infected with HIV and 0.45 to 0.68 in children infected with HIV (Table 3). IGRA-positivity in children negative for TST occurred more often in children not infected with HIV and for the QFT (6.8%) than the TSpot (4.3%). The mean QFT response was 18.5 IU/ml (SD, 9.8) in TST concordant and 16.7 IU/ml (SD, 7.8) in TST discordant samples. TST-QFT positive concordance was more common among children with a QFT response greater than 5 IU/ml and negative concordance with a QFT response less than 5 IU/ml. There was no association between discordance patterns and the magnitude of QFT response (see Table E5). Overall, IGRA-negativity in children positive for TST occurred in 11%, and in 19% of children infected with HIV. IGRA-negative/TST-positive discordance was more common in children with limited or no documented contact compared with those with more substantial contact (see Table E4). Test agreement did not vary using the composite measure of TB infection rather than the baseline measure only.

Table 3.

Agreement for Tests of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection and Discordance between Tests Stratified by HIV Status in Children

| TST versus TSpot Discordant Results |

TST versus QFT Discordant Results |

TSpot versus QFT Discordant Results | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSpot +ve TST −ve [n/N (%)] | TSpot −ve TST +ve* [n/N (%)] | κ (95% CI) | QFT +ve TST −ve [n/N (%)] | QFT −ve TST +ve* [n/N (%)] | κ (95% CI) | TSpot +ve QFT −ve [n/N (%)] | TSpot −ve QFT +ve [n/N (%)] | κ (95% CI) | |

| Baseline measures | |||||||||

| All children | 42/983 (4.3) | 108/983 (11.0) | 0.66 (0.61–0.71) | 85/1,246 (6.8) | 79/1,246 (6.3) | 0.73 (0.69–0.77) | 23/940 (2.4) | 72/940 (7.7) | 0.78 (0.73–0.82) |

| Children infected with HIV | 4/259 (1.5) | 49/259 (18.9) | 0.45 (0.33–0.56) | 12/267 (4.5) | 41/267 (15.4) | 0.50 (0.38–0.61) | 5/245 (2.0) | 19/245 (7.8) | 0.68 (0.56–0.80) |

| Children not infected with HIV | 38/724 (5.2) | 59/724 (8.2) | 0.71 (0.66–0.77) | 73/979 (7.5) | 38/979 (3.9) | 0.77 (0.73–0.81) | 18/695 (2.6) | 53/695 (7.6) | 0.78 (0.74–0.83) |

| Composite measures† | |||||||||

| All children | 38/1,052 (3.6) | 111/1,052 (10.6) | 0.70 (0.66–0.75) | 83/1,310 (6.3) | 97/1,310 (7.4) | 0.72 (0.68–0.76) | 29/1,046 (2.8) | 73/1,046 (7.0) | 0.79 (0.76–0.83) |

| Children infected with HIV | 8/287 (2.8) | 56/287 (19.5) | 0.46 (0.36–0.57) | 14/290 (4.8) | 50/290 (17.2) | 0.49 (0.38–0.59) | 11/287 (3.8) | 23/287 (8.0) | 0.66 (0.56–0.77) |

| Children not infected with HIV | 30/765 (3.9) | 55/765 (7.2) | 0.77 (0.73–0.82) | 66/1,020 (6.8) | 47/1,020 (4.6) | 0.77 (0.73–0.81) | 18/759 (2.4) | 50/759 (6.6) | 0.82 (0.78–0.86) |

Definition of abbreviations: +ve = positive; −ve = negative; CI = confidence interval; QFT = QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube; TSpot = T-SPOT.TB; TST = tuberculin skin test.

TST greater than or equal to 10 mm was considered as positive for participants uninfected with HIV and TST greater than or equal to 5 mm for participants infected with HIV.

M. tuberculosis infection status defined considering both baseline and 3-month test results. A child was defined as infected by a specific test if positive at either baseline or 3 months.

Child Characteristics Associated with Test Performance in Multivariate Analysis

While controlling for the effect of all variables (adjusted models), the odds of TST, QFT, and TSpot positivity increased 17, 18, and 21% for each 1-point increase in the contact score, respectively. For all tests, the odds of test positivity increased 1% for each increasing month of age (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association between Tests of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection and Covariates of Interest in Children

| Covariates | TST* [Odds Ratio (95% CI)] |

TSpot [Odds Ratio (95% CI)] |

QFT [Odds Ratio (95% CI)] |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted† |

Unadjusted |

Adjusted† |

Unadjusted |

Adjusted† |

|

| (n = 1,324) | (n = 1,315) | (n = 991) | (n = 986) | (n = 1,261) | (n = 1,253) | |

| TB contact score | 1.16 (1.11–1.22)‡ | 1.17 (1.11–1.23)‡ | 1.23 (1.16–1.29)‡ | 1.21 (1.14–1.29)‡ | 1.21 (1.16–1.26)‡ | 1.18 (1.12–1.24)‡ |

| BCG vaccination (referent: unvaccinated) | 1.30 (0.85–1.99) | 1.91 (1.07–3.42)§ | 1.44 (0.92–2.24) | |||

| Prior TB treatment (referent: no prior treatment) | 1.47 (0.93–2.31) | 1.96 (1.13–3.41)§ | 2.74 (1.64–4.45)‡ | |||

| Age (years) effect | 1.01 (1.01–1.02)‡ | 1.01 (1.01–1.02)‡ | 1.02 (1.01–1.02) | |||

| HAZ score effect | ||||||

| HIV-uninfected | 0.99 (0.94–1.04) | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | |||

| HIV-infected | 1.29 (1.07–1.57)§ | 1.19 (1.00–1.40)§ | 1.30 (1.05–1.61)§ | |||

| HIV effect (referent: HIV-infected)|| | ||||||

| HAZ score, 0 | 0.61 (0.35–1.04) | 1.85 (1.04–3.28)§ | 1.55 (0.85–2.82) | |||

| HAZ score, −1 | 0.79 (0.51–1.23) | 2.21 (1.32–3.70)§ | 2.02 (1.23–3.33)§ | |||

| HAZ score, −2 | 1.04 (0.69–1.56) | 2.64 (1.58–4.40)§ | 2.66 (1.65–4.28)‡ | |||

Definition of abbreviations: BCG = bacillus Calmette-Guérin; CI = confidence interval; HAZ = height for age z score; QFT = QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube; TB = tuberculosis; TSpot = T-SPOT.TB; TST = tuberculin skin test.

TST greater than or equal to 10 mm was considered as positive for participants uninfected with HIV and TST greater than or equal to 5 mm for participants infected with HIV.

Logistic regression adjusted for age, prior BCG vaccination, prior TB treatment, chronic malnutrition status, and HIV status. All models included interaction for HIV status and HAZ score.

Significant difference at P < 0.001.

Significant difference at P < 0.05.

Fixed HAZ score status (0, −1, and −2) represents no, mild, and moderate chronic malnutrition.

The TSpot and QFT were 2 and 2.7 times more likely to be positive in children with previous TB treatment than children without (Table 4).

There was an interaction between HIV status and chronic malnutrition (stunting; height-for-age z score) in all models. Among children infected with HIV, tests were less likely to be positive as stunting worsened (Table 4). The association between test positivity and acute malnutrition (wasting; weight-for-height z score) was not retained in multivariate regression models.

In the TST and QFT models, test positivity was not associated with BCG vaccination. In the TSpot model, test positivity was almost twofold higher in BCG-vaccinated than -unvaccinated children (Table 4); among children less than or equal to 5 years, BCG-vaccinated children were 5.5 times more likely to be TSpot positive. Results of TST and QFT regression analysis did not change in age-stratified subgroups.

For all tests, results of regression analysis did not change when children diagnosed with TB within 3 months of enrollment were excluded or when the composite measure of infection was considered.

Comparison of Test Performance for the Detection of M. tuberculosis Infection

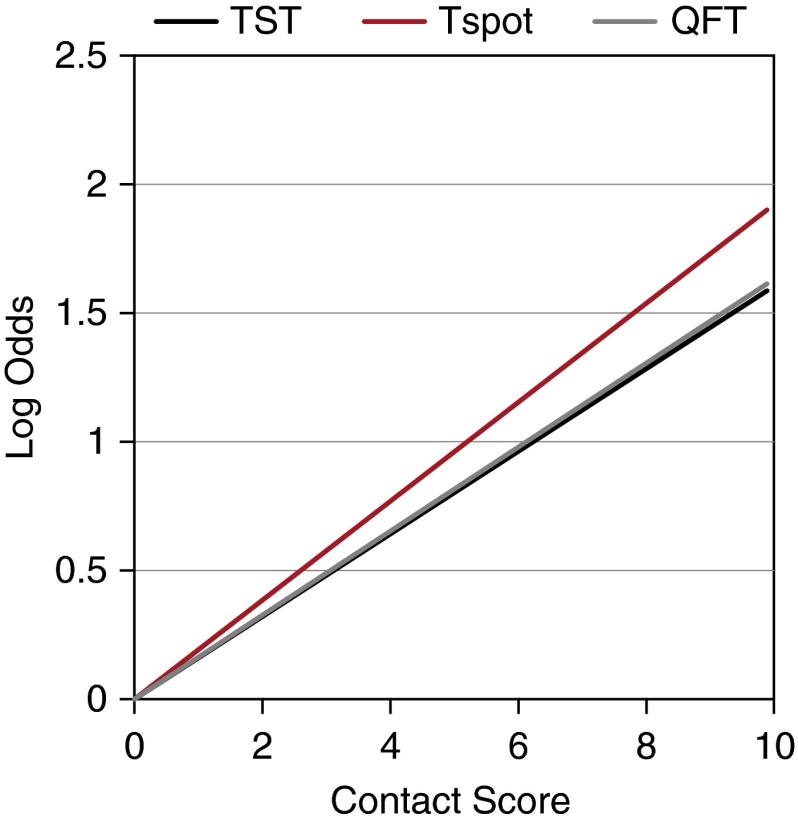

Regression of the log of the odds ratios illustrated that positivity of all tests increases as TB exposure increases with TSpot having the highest rate of increase (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Regression slopes for exposure continuum expressed as contact score. To visually represent the association between the contact score and test outcome, the odds ratio for each positive level of the score versus a zero score was estimated from each adjusted logistic regression model. The natural logarithm of the odds ratio was then plotted against the contact score to allow for comparison between the tests. The slopes of the lines are estimated from the regression of the logs of odds ratios of each successive higher exposure compared with the least exposed group. Hence, a steeper slope represents a greater change in the log odds ratio as exposure increases. A greater change in the log odds ratio in response to increasing exposure (i.e., steeper slope) indicates that test results are better correlated with the likelihood of infection. This finding suggests that tests with a steeper slope are better able to detect infection. QFT = QuantiFERON; Tspot = T-Spot.TB; TST = tuberculin skin test.

Generalized estimating equation modeling illustrated that the effect of the contact score on each test was significantly different (P = 0.0004). The association between an increasing contact score and test positivity was greater for both IGRAs than TST, and did not differ between TSpot and QFT.

In models using combinations of two baseline tests, test results and contact score were significantly associated (P < 0.0001); more so for the TSpot-QFT combination than the TST-TSpot and TST-QFT combination (P = 0.0011).

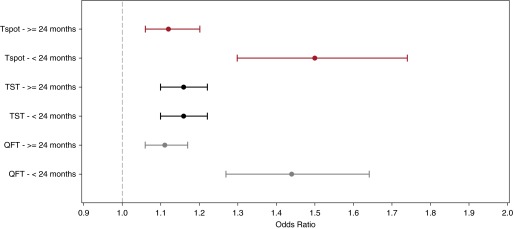

In models including age dichotomized at 24 months, there was no association between age and TST. In contrast, IGRAs were more strongly associated with contact score in younger children (P < 0.0001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Odds ratio of test positivity in young children compared with older children. The figure compares the aOR of test positivity for each test in children younger than 24 months compared with children greater than or equal to 24 months. The aOR are indicated by the circles and the 95% confidence intervals are illustrated with the lines; Tspot in red, TST in black, and QFT in gray. For the QFT model and the Tspot, there were interactions between age and contact score. Hence, the association between the IFN-γ release assay results and contact score is most accurately measured within each of the respective age strata. The aOR of QFT positivity was higher for younger children (P < 0.001): children younger than 24 months, aOR of 1.44 (95% CI, 1.27–1.64) and children greater than or equal to 24 months, aOR of 1.11 (95% CI, 1.06–1.17). Similarly, the aOR of Tspot positivity was higher for younger children (P < 0.001): children younger than 24 months, aOR of 1.50 (95% CI, 1.30–1.74) and children greater than or equal to 24 months, aOR of 1.12 (95% CI, 1.06–1.20). For the TST model, there was no significant association between age and TST result. Therefore, the aOR of TST was 1.16 (95% CI, 1.10, 1.22) for children younger than and greater than or equal to 24 months. aOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; QFT = QuantiFERON; Tspot = T-Spot.TB; TST = tuberculin skin test.

Discussion

The WHO aims to eliminate TB by the year 2050. Global TB elimination depends on many activities including LTBI treatment to reduce potential disease burden. Targeted LTBI treatment has been a TB control strategy for more than a decade (27), but remains hampered by poor LTBI detection and PT implementation. Our study provides new data and demonstrates some advantages of IGRAs for LTBI detection in children who are young, malnourished, and infected with HIV with recent TB contact, those children at highest risk of TB progression (2).

The high proportion of children with undocumented or minimal TB exposure who had LTBI demonstrates substantial community exposure and past infection in this high-burden setting. Among children with no documented contact and increasing TB exposure, TST and QFT positivity remained greater than TSpot positivity and would result in treating a higher proportion of children with little to no documented TB exposure. Positivity of all tests steadily increased among children with contact scores greater than or equal to 4, likely reflecting recent infection and supporting targeted screening among children with higher risk of LTBI (higher pretest probability) in conjunction with tests of infection to guide delivery of PT.

The lack of a gold standard for LTBI complicates studies of diagnostic accuracy (23). The association between IGRA positivity and TB exposure is well described in low-burden countries (28–30). Our regression analysis included a standardized measure of recent M. tuberculosis exposure (20) previously associated with IGRA and TST positivity in child contacts in high-burden settings (31, 32). These studies provide conflicting evidence and suggest both advantages of the TSpot (31) and no difference in TSpot performance compared with TST and QFT (32). Previously published pooled analysis retrospectively standardizing measures of M. tuberculosis exposure was unable to identify a superior test of infection (13). Strengthened by our prospective approach, comprehensive quantification of TB exposure, and robust sample size, we developed a model that accounts for covariates and demonstrates that IGRAs correlate better with TB exposure than the TST (P = 0.0011). Further longitudinal research is needed to fully understand the practical significance of these findings.

Similar to data from other pediatric studies (32, 33), nearly 8% of children in our study were IGRA-positive/TST-negative, thus potentially identifying an additional 81 children with LTBI. Lack of association between this discordance pattern and the magnitude of the QFT response argues against QFT false-positivity. This pattern of discordance occurred more frequently with QFT than TSpot and more commonly in children not infected with HIV, who were also more likely to have had recent TB exposure because of our recruitment strategy. Among Indian children identified with presumed TB detected through active case finding, the IGRA-positive/TST-negative pattern occurred in only 3% (34). However, in that study, a positive TST was an inclusion criterion and introduced a selection bias decreasing the frequency of the IGRA-positive/TST-negative pattern. Using IGRA testing only after positive TST is recommended by UK guidelines (17), but as we have shown, may miss recent M. tuberculosis infection.

Similar to studies in low-burden settings (35, 36), IGRA-negativity in children positive for TST occurred more often in children with little to no contact, suggesting that a portion of these TST results were false positives. We noted this discordance pattern in 19% of children infected with HIV who were more likely to have been evaluated and treated for TB. We hypothesize that frequent TST may have had a boosting effect. This finding may suggest that TST lacks specificity for detecting recent M. tuberculosis infection in HIV coinfected children. Because IGRAs were associated with past TB treatment in our study unlike TST, the IGRA-negative/TST-positive pattern is unlikely to reflect a subclinical, quiescent mycobacterial phase following treatment. Nevertheless, the absence of a gold standard of infection precludes confirmation of TST false positivity.

Among children infected with HIV, tests were less likely to be positive as chronic malnutrition (stunting) worsened. Delayed initiation of cART is associated with long-term impairment of M. tuberculosis–specific immune response (37). Adults infected with HIV can have an impaired effector memory pool of CD4 T cells despite normal or restored CD4 counts (38, 39), which may impair IFN-γ secreting ability. We suspect that children infected with HIV with evidence of stunting had advanced immune suppression at cART initiation with impairment of mycobacterial immune response and depressed IFN-γ production. Consistent with a smaller pediatric study (40), our findings in a larger, more diverse, community-based setting further confirm the compromised performance of TST and IGRAs in children who are malnourished and children infected with HIV highlighting the need for additional data to guide population-specific test interpretation.

With the high annual and age-related risk of M. tuberculosis infection in high-burden TB settings, older children were more likely to have positive tests of infection. Unlike previous studies (33, 41, 42), we detected no difference in IGRA performance or the frequency of indeterminate results in younger children, even in children 6 months of age. These contradictory findings likely result from differences in covariates considered and study populations (i.e., contacts vs. children with broadly defined presumed TB and administrative screening). Consistent with our findings, the performance of IGRAs did not diminish among Thai children aged 2 months to 16 years (32) and children younger than 5 years of age have sufficient immunologic capacity for IFN-γ production quantified by the QFT (43). Our findings suggest that even in young children test performance improves in a population with increased risk of infection, such as household contacts.

Studies of children not infected with HIV have found an association between BCG vaccination and IGRA-negativity suggesting a BCG protective effect against LTBI (30, 33). However, we found no association between BCG vaccination and QFT, and a positive association between BCG vaccination and TSpot. Our current analysis does not support a definitive interpretation of this finding.

The sensitivity of detecting M. tuberculosis infection in children with TB was comparable among the three tests. Similar to the TST, IGRAs cannot differentiate between TB infection and disease and a negative result does not exclude TB. Clinically significant TB exposure, symptoms, and chest radiography remain the cornerstone of TB diagnosis in children.

Baseline test sensitivity was low among children diagnosed with TB more than 6 weeks following enrollment, suggesting that none of the tests have ability to forecast TB disease. Replication of these findings in a cohort with extended follow-up may provide additional insight.

Despite our large, representative cohort, our study has limitations. Our measure of TB exposure may most accurately measure household TB exposure in children not infected with HIV. To accommodate this limitation, we controlled for HIV status and age, and included a control group with no documented TB exposure to measure background community exposure. Analyses in this control group supported interpretation of regression models and assessment of the influence of background community TB exposure. Our analysis did not consider the HIV status of the source case because of colinearity between HIV status of source case and child. We preferentially included the child’s HIV status in models because it was biologically more relevant to our questions. Our recruitment strategy captured children infected with HIV routinely attending antiretroviral clinic who were less likely to have documented recent TB exposure. We adjusted for this difference by including a measure of TB exposure in all regression models. Assessment of prognostic utility and confirmation of the erroneous result in the case of test discordance requires analysis of longitudinal disease outcomes in the absence of PT beyond the scope of this manuscript. We did not measure micronutrient levels or helminth status, which may affect test performance (34, 42). Our results may underestimate the frequency of indeterminate and false-negative results encountered in routine care settings.

Our study provides new evidence to inform TB screening and contact investigation guidelines. Contact tracing detects TB in nearly 8% of child contacts within 3 months of recent exposure. In a robust model accounting for confounders, IGRAs correlated better with TB contact than the TST in children with recent TB exposure. The IGRA-positive/TST-negative discordance pattern occurred at clinically significant rates, suggesting that screening algorithms using stepwise testing with IGRA only after positive TST (17) may under detect LTBI in children.

Where resources allow, IGRAs can potentially improve LTBI detection, guide targeted PT, and improve TB control in children. Paradoxically, increased investment in IGRAs may increase the value of PT in a public health setting. Because of financial constraints, IGRAs are currently not recommended by the WHO in low- and middle-income countries where TB incidence is greatest. Models using 2011 estimates of IGRA performance suggest that provision of PT to contacts without testing for infection is the most cost-effective strategy in children younger than 3 years of age in high-burden settings (44). However, this strategy overburdens health systems struggling to provide PT to large numbers of TB-exposed children and children infected with HIV with consequent overtreatment, poor adherence, and incongruous allocation of limited resources. An affordable and even more accurate test of infection is still urgently needed and could dramatically impact global TB control.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the children and families who graciously participated in the study. Special thanks is given to Claudia Francis, Felicity Stevens, Bradley Isaacs, Catherine Wiseman, Susan van Wyk, Karen Du Preez, Nelda van Soelen, Heidi van Deventer, and other members of the Desmond Tutu TB Centre Childhood TB team for the endless support. The authors also thank Belinda Kriel, and Angela Menezes from the SUN Immunology Group at Stellenbosch University for laboratory support and completion of interferon-γ release assays.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health NIAID (R01A076199), Thrasher Research Fund (02826), Norwegian Cooperation for Higher Education (NUFUPRO2007/10183), US Fulbright Scholar Program, and Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics.

Author Contributions: A.M.M., H.L.K., R.P.G., and A.C.H. designed the study. A.M.M. and A.C.H. alternately served as on-site project leaders during study implementation. A.M.M. and H.L.K. planned and executed the statistical analyses, which were reviewed by all authors. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings. A.M.M. wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors commented extensively, critically revised the report, and approved the final version.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1165OC on January 26, 2015

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Sloot R, Schim van der Loeff MF, Kouw PM, Borgdorff MW. Risk of tuberculosis after recent exposure. A 10-year follow-up study of contacts in Amsterdam. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:1044–1052. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1159OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marais BJ, Gie RP, Schaaf HS, Hesseling AC, Obihara CC, Starke JJ, Enarson DA, Donald PR, Beyers N. The natural history of childhood intra-thoracic tuberculosis: a critical review of literature from the pre-chemotherapy era. Int J Tubercul Lung Dis. 2004;8:392–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smieja M, Marchetti C, Cook D, Smaill F. Isoniazid for preventing tuberculosis in non-HIV infected persons. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1999;(1):CD001363. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woldehanna S Volmink J. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in HIV infected persons. Cochrane Databases Syst Rev. 2004;(1):CD000171. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000171.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu KH. Isoniazid in the prevention and treatment of tuberculosis. A 20-year study of the effectiveness in children. JAMA. 1974;229:528–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayieko J, Abuogi L, Simchowitz B, Bukusi EA, Smith AH, Reingold A. Efficacy of isoniazid prophylactic therapy in prevention of tuberculosis in children: a meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:91. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodd PJ, Gardiner E, Coghlan R, Seddon JA. Burden of childhood tuberculosis in 22 high-burden countries: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e453–e459. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70245-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Getahun H, Sculier D, Sismanidis C, Grzemska M, Raviglione M. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of tuberculosis in children and mothers: evidence for action for maternal, neonatal, and child health services. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:S216–S227. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Trends in tuberculosis—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:181–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pareek M, Bond M, Shorey J, Seneviratne S, Guy M, White P, Lalvani A, Kon OM. Community-based evaluation of immigrant tuberculosis screening using interferon gamma release assays and tuberculin skin testing: observational study and economic analysis. Thorax. 2012;68:230–239. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health OrganizationGuidance for national tuberculosis programmes on the management of tuberculosis in children. Geneva: WHO2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersen P, Munk ME, Pollock JM, Doherty TM. Specific immune-based diagnosis of tuberculosis. Lancet. 2000;356:1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02742-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandalakas AM, Detjen AK, Hesseling AC, Benedetti A, Menzies D. Interferon-gamma release assays and childhood tuberculosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Tubercul Lung Dis. 2011;15:1018–1032. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Machingaidze S, Wiysonge CS, Gonzalez-Angulo Y, Hatherill M, Moyo S, Hanekom W, Mahomed H. The utility of an interferon gamma release assay for diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection and disease in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:694–700. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318214b915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pareek M, Baussano I, Abubakar I, Dye C, Lalvani A. Evaluation of immigrant tuberculosis screening in industrialized countries. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:1422–1429. doi: 10.3201/eid1809.120128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazurek M, Jereb J, Vernon A, LoBue P, Goldberg S, Castro K. Updated guidelines for using interferon gamma release assays to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection—United States, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions, Centre for Clinical Practice at NICE.Tuberculosis: clinical diagnosis and management of tuberculosis, and measures for its prevention and control. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2011

- 18.World Health OrganizationUse of tuberculosis interferon-gamma release assays in low- and middle-income countries. Geneva: WHO; 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corrigal J.Western Cape Provincial EPI vaccination survey [serial online]. 2005[cited 2009 September 29]. Available from: www.capegateway.gov.za/Text/2007/6/cd_volume_7_childhood_diseases_overview.pdf

- 20.Mandalakas A, Kirchner HL, Lombard C, Wazyl G, Gie R, Hesseling A. Well quantified tuberculosis exposure is a reliable surrogate measure of tuberculosis infection in children. Int J Tubercul Lung Dis. 2012;16:1033–1039. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marais BJ, Gie RP, Hesseling AC, Schaaf HS, Lombard C, Enarson DA, Beyers N. A refined symptom-based approach to diagnose pulmonary tuberculosis in children. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1350–e1359. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marais BJ, Gie RP, Schaaf HS, Starke JR, Hesseling AC, Donald PR, Beyers N. A proposed radiological classification of childhood intra-thoracic tuberculosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:886–894. doi: 10.1007/s00247-004-1238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig LM, Lijmer JG, Moher D, Rennie D, de Vet HC Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy. Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: the STARD initiative. BMJ. 2003;326:41–44. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7379.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diggle P, Liang K, Zeger S.Analysis of longitudinal data. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:1049–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Thoracic Society. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(Suppl 3):S221–S247. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.supplement_3.ats600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arend SM, Thijsen SF, Leyten EM, Bouwman JJ, Franken WP, Koster BF, Cobelens FG, van Houte AJ, Bossink AW. Comparison of two interferon-gamma assays and tuberculin skin test for tracing tuberculosis contacts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:618–627. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1099OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ewer K, Deeks J, Alvarez L, Bryant G, Waller S, Andersen P, Monk P, Lalvani A. Comparison of T-cell-based assay with tuberculin skin test for diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in a school tuberculosis outbreak. Lancet. 2003;361:1168–1173. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12950-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soysal A, Millington KA, Bakir M, Dosanjh D, Aslan Y, Deeks JJ, Efe S, Staveley I, Ewer K, Lalvani A. Effect of BCG vaccination on risk of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children with household tuberculosis contact: a prospective community-based study. Lancet. 2005;366:1443–1451. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67534-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hesseling AC, Mandalakas AM, Kirchner HL, Chegou NN, Marais BJ, Stanley K, Zhu X, Black G, Beyers N, Walzl G. Highly discordant T cell responses in individuals with recent exposure to household tuberculosis. Thorax. 2009;64:840–846. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.085340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tieu HV, Suntarattiwong P, Puthanakit T, Chotpitayasunondh T, Chokephaibulkit K, Sirivichayakul S, Buranapraditkun S, Rungrojrat P, Chomchey N, Tsiouris S, et al. Thai TB Px Study Group. Comparing interferon-gamma release assays to tuberculin skin test in Thai children with tuberculosis exposure. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Basu Roy R, Sotgiu G, Altet-Gómez N, Tsolia M, Ruga E, Velizarova S, Kampmann B. Identifying predictors of interferon-γ release assay results in pediatric latent tuberculosis: a protective role of bacillus Calmette-Guerin? A pTB-NET collaborative study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:378–384. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0026OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jenum S, Selvam S, Mahelai D, Jesuraj N, Cardenas V, Kenneth J, Hesseling A, Doherty M, Vaz M, Grewal H. Influence of age and nutritional status on the performance of the tuberculin skin test and QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube in young children evaluated for tuberculosis in Southern India. Ped Infectious Dis J. 2014;33:e260–e269. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cruz AT, Geltemeyer AM, Starke JR, Flores JA, Graviss EA, Smith KC. Comparing the tuberculin skin test and T-SPOT.TB blood test in children. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e31–e38. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rose W, Read S, Bitnun A, Rea E, Stephens D, Pongsamart W, Kitai I. Relating tuberculosis (TB) contact characteristics to QuantiFERON-TB-Gold and tuberculin skin test results in the Toronto pediatric TB clinic. J Ped Infect Dis [online ahead of print] 8 Apr 2014; DOI: 10.1093/jpids/piu024. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Lawn SD, Badri M, Wood R. Tuberculosis among HIV-infected patients receiving HAART: long term incidence and risk factors in a South African cohort. AIDS. 2005;19:2109–2116. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000194808.20035.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sutherland R, Yang H, Scriba TJ, Ondondo B, Robinson N, Conlon C, Suttill A, McShane H, Fidler S, McMichael A, et al. Impaired IFN-gamma-secreting capacity in mycobacterial antigen-specific CD4 T cells during chronic HIV-1 infection despite long-term HAART. AIDS. 2006;20:821–829. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000218545.31716.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsieh SM, Hung CC, Pan SC, Wang JT, Tsai HC, Chen MY, Chang SC. Restoration of cellular immunity against tuberculosis in patients coinfected with HIV-1 and tuberculosis with effective antiretroviral therapy: assessment by determination of CD69 expression on T cells after tuberculin stimulation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;25:212–220. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200011010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mandalakas AM, van Wyk S, Kirchner HL, Walzl G, Cotton M, Rabie H, Kriel B, Gie RP, Schaaf HS, Hesseling AC. Detecting tuberculosis infection in HIV-infected children: a study of diagnostic accuracy, confounding and interaction. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;32:e111–e118. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31827d77b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Critselis E, Amanatidou V, Syridou G, Spyridis NP, Mavrikou M, Papadopoulos NG, Tsolia MN. The effect of age on whole blood interferon-gamma release assay response among children investigated for latent tuberculosis infection. J Pediatr. 2012;161:632–638. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mukherjee A, Saini S, Kabra SK, Gupta N, Singh V, Singh S, Bhatnagar S, Saini D, Grewal HM, Lodha R Delhi TB Study Group. Effect of micronutrient deficiency on QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube test and tuberculin skin test in diagnosis of childhood intrathoracic tuberculosis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68:38–42. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2013.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Riazi S, Zeligs B, Yeager H, Peters SM, Benavides GA, Di Mita O, Bellanti JA. Rapid diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children using interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs) Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012;33:217–226. doi: 10.2500/aap.2012.33.3574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mandalakas AM, Hesseling AC, Gie RP, Schaaf HS, Marais BJ, Sinanovic E. Modelling the cost-effectiveness of strategies to prevent tuberculosis in child contacts in a high-burden setting. Thorax. 2012;68:247–255. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]