Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

Central to health insurance reform discussions was the recurring question: why are eligible children not enrolled in public insurance programs? We interviewed families with children eligible for public insurance to (1) learn how they view available services and (2) understand their experiences accessing care.

METHODS

Semi-structured, in-depth interviews with 24 parents of children eligible for public coverage but not continuously enrolled were conducted. We used a standard iterative process to identify themes, followed by immersion/crystallization techniques to reflect on the findings.

RESULTS

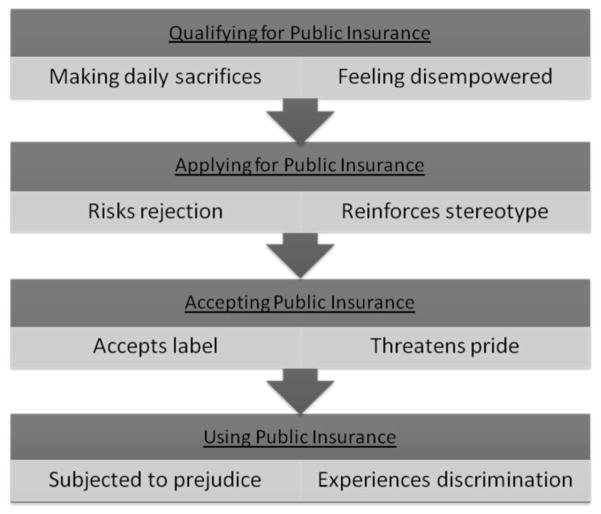

Respondents identified four barriers: (1) confusion about insurance eligibility and enrollment, (2) difficulties obtaining public coverage and/or services, (3) limited provider availability, and (4) non-covered services and/or coverage gaps. Regardless of whether families had overcome these barriers, all had experienced stigma associated with needing and using public assistance. There was not just one point in the process where families felt stigmatized. It was, rather, a continual process of stigmatization. We present a theoretical framework that outlines how families continually experience stigma when navigating complex systems to obtain care: when they qualify for public assistance, apply for assistance, accept the assistance, and use the public benefit. This framework is accompanied by four illustrative archetypes.

CONCLUSIONS

This study provides further insight into why some families forego available public services. It suggests the need for a multi-pronged approach to improving access to health care for vulnerable children, which may require going beyond incremental changes within the current system.

Central to the controversy surrounding the reauthorization of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) in the United States was the recurring question—why are eligible children not enrolled?1,2 Having health insurance coverage improves financial access to care, yet an estimated two thirds of uninsured US children are eligible for public coverage.3–6 Not surprisingly, states with more extensive enrollment requirements have higher rates of eligible children not enrolled.7,8 Further, some parents know their uninsured child is eligible but voluntarily forego the option to enroll.2

Health disparities are due, in part, to differential access to and use of health insurance.3–5,9–11 However, narrowing disparities will require more than expanding public insurance programs. Beyond insurance, access to services requires not only a way to pay for services but also a place to obtain care—both financial access and structural access.3,12–16 Federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and many community-oriented primary care clinicians provide vital structural access in underserved communities.4,17–19 Just as expanding insurance is not the ultimate solution, it is unlikely that increasing the supply of safety net services will solve all access problems.

Understanding why eligible children are not enrolled in public insurance programs, why others cannot access basic health care services, and how to fix these complex problems will be central to the success of any state or federal health insurance reform efforts. Further, this important research task calls for expanding upon commonly used methodologies. Secondary analyses of administrative claims and utilization data, or household surveys, quantify the numbers of eligible children not enrolled, but most do not explore families’ decision-making processes.14,20–22 Even studies that incorporate qualitative methods to achieve more in-depth analyses usually target insurance administrators, health professionals, families enrolled in Medicaid/CHIP, or patients recruited from physicians’ offices. These approaches can miss key insights from invisible families who have no insurance coverage and/or who rarely visit health care facilities. The primary purpose of this study was to learn how families with children eligible but not continuously enrolled in public insurance programs view insurance and health care resources available to their children. Secondarily, we wanted to gain a better understanding of the personal experiences these families faced when accessing public resources. To our knowledge, limited information is available on these topics from the point of view of the families themselves. Specifically, this study was designed to add richness and depth to the current literature by exploring the lived experiences of families struggling to provide adequate health care for their children.

Methods

This study used a qualitative approach: semi-structured, in-depth interviews with 24 families who responded to the Oregon Children’s Access to Healthcare Study (CAHS) survey in 2005, which surveyed a stratified, random sample of Oregon families receiving food stamps. The survey was intended to collect quantitative data regarding why eligible children were not enrolled in the Oregon Health Plan (Oregon’s combined Medicaid and CHIP). More details about CAHS sampling procedures and findings are reported elsewhere.5,23,24

For this qualitative phase of the study, we purposefully identified all CAHS respondent families who had a child with no insurance coverage (coverage gap) for at least 1 month during the prior year (n=851), then selected a random sample of approximately half of these respondents (n=432). In July 2008, we sent informational letters, in both English and Spanish, to all families describing our intent to have a researcher contact them to set up an interview. The letter provided an opportunity to leave a voicemail message declining further contact or to update telephone numbers; we received five refusals via this method. Sixty-four letters were returned with no forwarding address, and an additional 228 families were found to have disconnected telephone numbers, leaving 135 potential participant households. Interviewers attempted to reach all potential participants with working telephone numbers, making up to five attempts, on different days at varied times. We talked with 48 individuals, and 24 agreed to participate in a face-to-face interview at a location of their choosing. Family informants who declined participation cited work or family obligations that precluded them from participating. There were no significant sociodemographic differences between those who agreed and those who refused participation. After completing interviews with 24 families, preliminary data analysis indicated that we had reached saturation on several major themes.25 We conducted descriptive analyses using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS+, Version 16.0) to confirm that this subsample represented a diverse group, with patterns of insurance discontinuity and unmet health care needs similar to the sample population (See Table 1 for comparison).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Qualitative Study Participants to Random Subsample of Children With Coverage Gaps

| Qualitative Study Participants n=24 (Unweighted %) | Qualitative Study Subsample With Coverage Gaps n=432 (Unweighted %) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Sociodemographics | ||

|

| ||

| Child’s age | ||

| 1–4 years | 20.8 | 25.4 |

| 5–9 years | 33.3 | 29.6 |

| 10–14 years | 25.0 | 28.0 |

| 15–18 years | 20.8 | 17.0 |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| White | 66.7 | 66.7 |

| Black | 8.3 | 2.2 |

| Other race/more than one race | 25.0 | 31.1 |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 20.8 | 23.4 |

| Not Hispanic | 79.2 | 76.6 |

|

| ||

| Parental employment | ||

| Not employed | 45.8 | 50.8 |

| Employed | 54.2 | 49.2 |

|

| ||

| Household income as % of federal poverty level (FPL) | ||

| 0 | 4.2 | 13.5 |

| 1%–50% FPL | 29.2 | 29.2 |

| 51%–100% FPL | 29.2 | 29.5 |

| 101%–133% FPL | 33.3 | 19.9 |

| >133% FPL | 4.2 | 7.8 |

|

| ||

| Child has special health care need(s) | ||

| No | 87.0 | 87.2 |

| Yes | 13.0 | 12.8 |

|

| ||

| Insurance descriptives | ||

|

| ||

| Child’s insurance status/type | ||

| Privately insured | 25.0 | 11.2 |

| Publicly insured | 25.0 | 46.1 |

| Not insured | 50.0 | 42.7 |

|

| ||

| Parent’s insurance status/type | ||

| Privately insured | 19.0 | 18.6 |

| Publicly insured | 4.8 | 28.6 |

| Not insured | 76.2 | 52.9 |

|

| ||

| Child continuity of insurance coverage | ||

| <6-month gap | 60.9 | 71.9 |

| >6-month gap | 39.1 | 28.1 |

|

| ||

| Oregon Health Plan enrollment status | ||

| Currently enrolled | 26.1 | 53.5 |

| Previous enrollment but not current | 52.2 | 41.0 |

| Never enrolled | 21.7 | 5.5 |

|

| ||

| How long since child had health insurance | ||

| <1 year or current enrollment | 70.9 | 77.3 |

| >1 year | 20.8 | 14.3 |

| Never had coverage | 8.3 | 6.4 |

|

| ||

| Health care utilization and unmet needs | ||

|

| ||

| Has no current usual source of care | 13.6 | 19.4 |

|

| ||

| Unmet medical need | 33.3 | 38.9 |

|

| ||

| Unmet prescription need | 29.2 | 38.0 |

|

| ||

| No doctor visit in past 12 months | 16.7 | 18.8 |

|

| ||

| Big problem accessing specialty care | 40.0 | 47.1 |

|

| ||

| Big problem accessing dental care | 47.8 | 46.5 |

Note: Oregon Health Plan is Oregon’s combined Medicaid and state children’s health insurance program

Two research assistants with in-depth interviewing skills conducted all interviews using the same semi-structured guide, which included a series of open-ended questions designed to elicit factual information as well as informants’ knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes about particular topics. Questions were designed to explore possible facilitators and barriers to children’s health insurance enrollment and health care service utilization. Interviewers asked respondents all questions in the same sequence, and they used inductive probing on key responses. Interviews were conducted statewide in both urban and rural areas throughout Oregon between July 8 and August 19, 2008; most were held in participants’ homes. One interview was conducted in Spanish. One interview was conducted with a father, one with both parents, one with a grandmother, and the remaining 21 were conducted with mothers. Prior to each interview, the interviewer reviewed consent documents and assisted participants in completing forms. Interviews averaged approximately 60–90 minutes in length. We digitally recorded (with participant agreement) all interviews and then subsequently transcribed all recordings in their entirety verbatim.

The qualitative analysis was done by a five-person, multidisciplinary team, including a physician researcher with doctoral training in both quantitative and qualitative research design and analysis (JD), a medical student from rural Oregon (NW), a medical student jointly enrolled in a public health master’s program (SC), a physician with rural practice experience, now enrolled in a public health master’s program (SS), and a physician with international practice experience, who recently completed a master’s in public health (DE). Each of the five team members independently read all 24 interview transcripts and identified themes. We used a standard iterative process to create an initial thematic codebook.26 We then repeated our individual reviews, this time examining transcripts line by line applying the codes to specific text and revising the codebook with group consensus throughout. This process allowed us to methodically examine our data until the patterns that emerged could be well substantiated and articulated. After completing the standard iterative process, we also conducted a series of immersion/ crystallization cycles.27 These cycles of immersion and crystallization allowed each team member to not only become immersed in the transcripts but also to temporarily suspend the process to reflect upon the findings and to articulate to one another the overarching patterns and inter-connectedness of themes that had emerged. This process culminated in the development of a theoretical framework and four representative narrative archetypes. We received guidance and feedback throughout the process from co-authors with expertise in health literacy/health communication (LW) and qualitative analytical techniques (AB).

The study protocol was approved by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board (OHSU eIRB# 1717).

Results

In the initial thematic analyses, four major themes emerged as potential explanations for why eligible children were not enrolled in public insurance and/or not receiving public care options, including (1) confusion about eligibility and enrollment requirements, (2) difficulties associated with the complexity of obtaining coverage and/or health care services, (3) frustrations with limited provider availability for those with public coverage, and (4) frequent experiences with non-covered services and/or coverage gaps (Table 2). The themes encompass four real and/or perceived system barriers that are well known from previous research.8,22,28,29

Table 2.

System Barriers to Public Health Insurance and Health Care Services for Children

(1) Confusion about public program eligibility and enrollment requirements

|

(2) Difficulties associated with the complexity of obtaining health insurance coverage and/or health care services

|

(3) Frustrations with limited provider availability for those with public coverage

|

(4) Frequent experiences with non-covered services and/or gaps in coverage

|

In the second phase of our analytical process, we used immersion/crystallization cycles to probe deeper into these themes and to better understand parents’ decision making and themes “under the surface.”27 While each respondent had unique stories and had taken somewhat different paths to overcome system barriers, a common and pervasive theme emerged: stigma. For every family, regardless of the path taken, the process of accessing insurance and services was disempowering on at least one level; many experienced stigma on multiple levels, feeling disgraced by their struggles to obtain care for their children. In the words of one parent who had watched her child’s dental health deteriorate while waiting months to gain access to dental care, “I just felt almost violated, in a way, because as a parent, you want to protect your children, and there wasn’t anything that I could do… That’s it! I came into the dentist, his teeth are gone, they had to be removed, and there wasn’t anything else that could be done.”

Through the immersion/crystallization process, we developed a new theoretical framework that encompasses the multiple levels of stigma associated with how families experienced the process. These concepts are intended to provide further insight into why some families might chose to forego available public services (Figure 1). To access care, parents had to take action that reinforced a stereotype, accepted a derogatory label, led to discrimination, and/or required personal compromise. As expressed by one respondent, “It’s not anything like you have to step to the side because you’re on [Medicaid], it’s not blatant, it’s just an overall feeling, the long waits for appointments, the select few doctors that will take it, so just all those things rolled into one makes you feel almost like you’re lower class or less important.”

Figure 1.

Layers of Stigma

The theoretical framework in Figure 1 illustrates the complexity of choices faced by parents and their associated experiences. First, simply qualifying for public insurance meant the family was disadvantaged, often feeling disempowered. Being in a “qualifying” low socioeconomic class, these families were already making sacrifices, choosing between basic needs such as food, housing, and health care. One parent remarked, “There were times we’d have to pick: ‘Let’s see, the first of the month, do we pay the insurance or do we pay the water, sewer, and electricity?’ So, there were a couple times we got behind because we had to make that decision. If you have to choose between water and electricity, and insurance you’re not using on a daily basis, you have to pick your utilities.” Parents wanted to provide the basic needs for their children and felt guilty when they were unable to do so. One mother reported, “It was really frustrating because you feel like—you’ve got children, you need to be able to provide for them…but we were struggling for groceries then; so, it was really hard.” Another mother expressed frustration with people who have never walked in her shoes, “Maybe they’ve never been poor, or had to live in their car, or had to stand in line for food...There are people that really just want to provide the best home they can for their kids, and part of that is being able to treat their kids when they’re sick and not worry about where the money is going to come from.”

Applying for public health insurance meant making an active choice to risk rejection and to reinforce stereotypes associated with poverty. One parent reported on her experience during the application process, “They look at you like ‘uh-ha, single white trash mom applying for the Oregon Health Plan.’ ‘No, I’m working three jobs, thank you.’” To make the choice to apply, parents weighed the benefits against the costs. If their child was healthy and few providers in their community accepted public insurance, the process was deemed not worth the cost. One mother dropped public insurance because she was concerned about the quality of care she could obtain: “The only problem was you had to take them to certain doctors, and those weren’t generally the best doctors, I didn’t trust their judgment…” Another parent reported, “It’s not like I want to have all the luxuries, it’s not like I want so much, only to be able to have private health insurance for the kids. It’s what I want most.”

Next, choosing to accept the assistance from public insurance was further stigmatizing because it accepted the label of being poor, further eroding a personal and family sense of pride. One parent remarked on the difficulty finding providers due to the stigma, “I was calling around to offices where it’s ‘no, no, no, we don’t deal with those kinds of people.’” Another reported on how she had to swallow her pride every time she had to provide insurance information, “Those ladies at the front desk are very snooty, they are very rude. As soon as people find out that you are on the Oregon Health Plan, it is a whole different ballgame than Blue Cross or Blue Shield.”

Finally, using public insurance subjected their family to potential prejudice from providers, and they experienced discrimination at the point of service. According to one parent, “As soon as the medical providers figure out that you are on the Oregon Health Plan, you are treated like a lower class citizen.” Similarly, another reported frustration with being turned away by an office that did not accept public insurance, “When you really have something you think your kid needs to be seen for, you want them in, you want it taken care of and there’s no bending on that, it’s not a matter of ‘can we talk about it?’ There’s no room for compromise.” Most respondents were grateful to have the option available to them but also felt bad about the system: “I’m one of the lucky few, as bad as this sounds, one of the lucky few that because I’m in severe poverty, I get health insurance, which is a shame, you either have to have a very nice income or have hardly any income…The middle class is so screwed. As bad as it sounds to be lucky to be in poverty, we’re lucky to be in poverty.” Table 3 outlines four archetypes, or empirical examples, based on data from this study that demonstrate how the framework in Figure 1 applies to the lived experiences of families in this study.

Table 3.

Four Archtypes Illustrating the Theoretical Layers of Stigma (Presented in Figure 1)

|

Qualifying for Public Insurance

|

| This family qualifies for public insurance, but they only obtain employer-sponsored insurance when they can afford it. Other times, they pay out-of-pocket, and care is rationed, delayed, or neglected. During hard times, all family resources are rationed, including food. At these times, getting injured or sick is feared the most. For them, health insurance is a coveted luxury—they wish their family could have private insurance “forever.” This family lives in fear, every day, of losing their private coverage, especially since mom’s coworker just lost her job. |

| They understand that no insurance is perfect. Their private plan has more options but at higher cost; public insurance would offer them fewer services but at minimal cost. For them, it is important to have access to providers based upon trust and experience, rather than type of insurance. They desire a simpler system with better continuity of care. Although they qualify for public coverage, they are too proud to apply. They have become accustomed to having access to the system while insured but to forego care while uninsured.

|

|

Applying for Public Insurance

|

| This family is frustrated with the public insurance application process. Last year, mom had to find a second job, so they lost their public insurance but could not afford private. Now, no one is insured, including the kids. Their kids may again qualify for public insurance, but repeating the onerous application process would take time away from work, which is top priority to be able to afford basic needs. Rationing of food and clothing is a daily reality. |

| They use alternative means of accessing health care. Sometimes, they borrow from family, which increases family tensions. Other times, they negotiate payment plans or shop around for cheaper options. Mostly, they wait until it is absolutely necessary to seek care, which heightens anxiety. They worry about a child falling ill, feel disempowered with few options for care, and live with the guilt of not being able to insure their children. Recently, their kids have been healthy, so the burden of applying for public insurance has not been worth it.

|

|

Accepting Public Insurance

|

| This single-parent family struggles every day to stay afloat. In the past, mom and her two kids were covered by public insurance; however, mom lost coverage last year after Medicaid eligibility rules changed. Mom worries about the limited access to providers with public insurance and is grateful that her children’s physician continues to accept Medicaid. She takes comfort in knowing she can bring her kids to their doctor whenever necessary but still worries about not being able to access dental care. |

| She believes accepting public coverage is worth it to her family because she has experienced the stress of being uninsured. In fact, she recently declined a $1.50/hour pay raise, for fear of losing her children’s insurance. She is frustrated that getting pregnant again would be the only way for her to access public coverage for herself.

|

|

Using Public Insurance

|

| This family desperately needs health insurance—of any type. Currently, the entire family is covered by public insurance, for which they are grateful. Several months ago, mom was diagnosed with a terminal illness. The “silver lining”: she now qualifies and has successfully obtained public disability and health insurance benefits, which have helped immensely with financial stressors. |

| Mom has a master’s degree, and dad was a high school dropout; both are confused by the processes to obtain health insurance and the fragmented way in which health care is delivered. They are frustrated by limited access to providers, and they wish their children had more options. Their insurance only covers some care, so they opt out of recommended treatments to avoid out-of-pocket costs, especially dental care and prescription medications. For them, however, the need for the public insurance outweighs the frustrations with using it. |

Discussion

Our study confirmed well-known barriers, outlined in Table 2, that prevent eligible children from staying continuously enrolled in public insurance programs.6–8,22,29 Beyond what is known, these findings provide policy-relevant insight about the lived experiences of families eligible for public insurance programs and their perceptions about the quality and acceptability of public programs. Even if new health insurance reform policies fix many of the system barriers, our findings suggest that layers of stigma might still remain. Through immersion/crystallizations techniques, we extended findings from existing literature by demonstrating the complexity of choices faced by low-income families. For some parents, the stigma associated with applying for, accepting, and using public health insurance was worth the hassle to gain necessary care for an ill child. For others, accepting derogatory labels and the risk of discrimination weighed heavily in decisions to forego coverage and/or care. Further, interviewees choosing to forego public options expressed feelings of shame and guilt about not being able to provide private insurance or a private clinic for their children.

This study highlights the need for innovative solutions—beyond current changes—to ensure that every child has access to care. For example, expanding the Children’s Health Insurance Program may give more children financial access and possibly improve the process of applying for insurance; however, it may not alleviate the stigma associated with accepting and using it. On the other hand, increasing the number of primary care providers, without total redesign of financing and delivery mechanisms, may not increase provider choice for parents using public insurance. (For example, it would be interesting to observe how access and stigma might change if public insurance paid the highest reimbursement rates rather than the lowest.)

Relevance to Policy and Practice

How can we minimize barriers to public care options, especially as health reform initiatives move toward mandates requiring all American families to obtain coverage? First, we must accept that investments in children’s health are a public good30 and support policies that expand public insurance programs (eg, Medicaid, CHIP), ease enrollment and retention barriers to coverage, expand public care options (eg, FQHCs), and achieve better coordination between current financing and delivery structures. These solutions and their effectiveness have been described in great detail elsewhere.2,7,22,31,32

As we take these steps, there is an important central consideration that must not be lost as reform initiatives are implemented: How can future reforms minimize stigma? As illustrated by our findings, addressing the root of the problem may be more complicated than making incremental changes within the current structure that expand CHIP and mandate coverage. Tackling some of the social determinants of health, including stigma, can lead to reductions in health-related disparities.33 If we persist with incremental reforms that expand stigmatizing programs, barriers to apply, and to accept and to use services will remain. As argued by Courtwright, stigma can create health disparities directly by impacting health-seeking behaviors and indirectly through an individual’s internalization of negative perceptions of him/herself.34 Further, incremental reforms propagate perverse incentives that keep people poor and enable private companies to continue their exclusions of the poor, disabled, and elderly—those most likely to have costly medical bills (paid by the government). Lastly, even if CHIP is incrementally expanded to allow universal eligibility for all children, the current model will not achieve universal coverage unless it adopts the same continuous coverage model provided to elders under Medicare.

Study Considerations

Our study has several limitations. First, we conducted the interviews in one state and limited the study to children with coverage gaps, thus the experiences described may reflect barriers encountered only by this population. The sub-sample (n=24) did include a demographically diverse group, with most characteristics similar to the original population of randomly selected families (n=432). Nonetheless, Oregon has fewer ethnic and racial minorities than many other states. By design, this qualitative study was not intended to obtain widely generalizeable results. Rather, it was intended to provide a rich, in-depth picture of individual experiences and to uncover new themes not explored by past research. Second, interviews were conducted by two interviewers, which may have contributed to response variability. We attempted to minimize this potential bias by providing standardized interview training and by using the same semi-structured questionnaire and probing techniques. We acknowledge the differential impact on the type of response given or the degree to which individuals felt at ease and willing to talk. The nature of open-ended qualitative interviews is not to be completely standardized but instead to reflect the respondents’ unique interests, attitudes, and circumstances. Third, we contacted participants 3 years after the initial survey, and many potential subjects had moved with no forwarding address or telephone numbers, as is common with this mobile population. Fourth, interviewers were representatives of an academic health center with inherent biases associated with their role. This may have biased how respondents answered certain questions. Finally, while we recruited a multidisciplinary group of reviewers representing different viewpoints, there is a certain inevitable degree of homogeneity in the perspectives of a highly educated group of researchers from an academic health center, which has the potential to bias the interpretation of qualitative data.

Conclusions

There are multiple explanations for why eligible children are not enrolled in public health insurance programs. We confirm previous evidence documenting the need to fix system barriers that prevent children from obtaining and maintaining public coverage. We present a theoretical discussion about the multiple layers of stigma experienced by families as they qualify for public insurance, apply for, accept, and use public coverage. Further recognition of these complex layers of stigma help to better explain why some families might continue to forego public health insurance and health care services for their children, even if system barriers were removed (and as mandates are implemented). It is important for policy-makers, researchers, and clinicians to understand the circumstances surrounding these families’ decision-making processes and experiences. Beyond reforms to fix both financial and delivery system barriers, we must think critically about whether proposed changes will preserve or eliminate associated stigmas.

Acknowledgments

Jennifer DeVoe’s time on this project was partially funded by grant numbers F32 HS014645, K08 HS16181, and R01 HS018569 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Nicholas Westfall’s and Stephanie Crocker’s time on this project was supported by a medical student research grant from the Oregon Health & Science University Department of Family Medicine.

References

- 1.US Bureau of the Census. Current population survey. Washington, DC: US Bureau of the Census; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sommers A, Dubay L, Blumberg L, Blavin F, Czajka J. Dynamics in Medicaid and SCHIP eligibility among children in SCHIP’s early years: implications for reauthorization. Health Aff. 2007;26(5):w598–w607. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.w598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starfield B. Access, primary care, and medical home: rights of passage. Med Care. 2008;46(10):1015–6. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817fae3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olson LM, Tang SF, Newacheck PW. Children in the United States with discontinuous health insurance coverage. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(4):382–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeVoe JE, Graham A, Krois L, Smith J, Fairbrother GL. “Mind the gap” in children’s health insurance coverage: does the length of a child’s coverage gap matter? Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8(2):129–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szilagyi PG, Schuster MA, Cheng TL. The scientific evidence for child health insurance. Academic Pediatrics. 2009;9(1):4–6. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kenney G, Yee J. SCHIP at a crossroads: experiences to date and challenges ahead. Health Aff. 2007;26(2):356–69. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fairbrother G, Dutton MJ, Bachrach D, Newell K-A, Boozang P, Cooper R. Costs of enrolling children in Medicaid and SCHIP. Health Aff. 2004;23(1):237–43. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phillips RJ, Bazemore A, Dodoo M, Shipman S, Green L. Family physicians in the child health care workforce: opportunities for collaboration in improving the health of children. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):1200–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevens GD, Seid M, Mistry R, Halfon N. Disparities in primary care for vulnerable children: the influence of multiple risk factors. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(2):507–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeVoe J, Graham A, Angier H, Baez A, Krois L. Obtaining healthcare services for low-income children: a hierachy of needs. J Healthc Poor Underserved. 2008;19(4):1192–1211. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Starfield B. Insurance and the US health care system. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(4):418–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newacheck P, Hughes D, Stoddard J. Children’s access to primary care: differences by race, income, and insurance status. Pediatrics. 1996;97:26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kemper AD, Diaz G, Jr, Clark J. Willingness of eye care practices to evaluate children and accept Medicaid. Amb Pediatr. 2004;4:303–7. doi: 10.1367/A03-203R.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mangione-Smith R, DeCristofaro AH, Setodji CM, et al. The quality of ambulatory care delivered to children in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(15):1515–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valet R, Kutny D, Hickson G, Cooper W. Family reports of care denials for children enrolled in TennCare. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e37–e42. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Starfield B, Shi L. The medical home, access to care, and insurance: a review of evidence. Pediatrics. 2004;113(Suppl):1493–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kempe A, Beaty B, Crane L, et al. Changes in access, utilization, and quality after enrollment into a state child health insurance plan. Pediatrics. 2005;155(2) doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shipman S, Lurie J, Goodman D. The general pediatrician: projecting future workforce supply and requirements. Pediatrics. 2004;113:435–42. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyers D, Mishori R, McCann J, Delgado J, O’Malley A, Fryer G. Primary care physicians’ perceptions of the effect of insurance status on clinical decision making. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(5):399–402. doi: 10.1370/afm.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang E, Choe M, Meara J, Koempel J. Inequality of access to surgical specialty health care: why children with goverment-funded insurance have less access than those with private insurance in Southern California. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e584–e590. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fairbrother GL, Emerson HP, Partridge L. How stable is Medicaid coverage for children? Health Aff. 2007;26(2):520–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeVoe J, Krois L, Edlund C, Smith J, Carlson N. Uninsurance among children whose parents are losing Medicaid coverage: results from a statewide survey of Oregon families. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(1 Part II):401–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00764.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeVoe JE, Krois L, Edlund C, Smith J, Carlson N. Uninsured but eligible children: are their parents insured? Recent findings from Oregon Med Care. 2007;46(1):3–8. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815b97ac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacQueen K, et al. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cultural Anthropology Methods Journal. 1998;10(12):31–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borkan J. Immersion/crystallization. In: Crabtree BF, Miller W, editors. Doing qualitative research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. pp. 179–94. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holahan J, Dubay LC, Kenney G. Which children are still uninsured and why: a Discussion Paper. Health Insurance for Children. The Future of Children; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Selden T, Hudson J. Access to care and utilization among children: estimating the effects of public and private coverage. Med Care. 2006;44(5 Suppl):I19–I26. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000208137.46917.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frick KD, Ma S. Overcoming challenges for the economic evaluation of investments in children’s health. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(3):136–7. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sommers B. Why millions of children eligible for Medicaid and SCHIP are uninsured: poor retention versus poor take-up. Health Aff. 2007;26(5):w560–w567. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.w560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hudson JL, Selden TM. Children’s eligibility and coverage: recent trends and a look ahead. Health Aff. 2007;26(5):w618–w629. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.w618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams DR, Costa MV, Odumlami AO, Mohammed SA. Moving upstream: how interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14 (Suppl):S8–S17. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000338382.36695.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Courtwright AM. Justice, stigma, and the new epidemiology of health disparities. Bioethics. 2009;23(2):90–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeVoe JE. EDUCAID: What if the US systems of education and health care were more alike? Fam Med. 2009;41(9):652–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]