Abstract

Angiogenesis inhibitors are beneficial for the prevention and treatment of angiogenesis-dependent diseases including cancer. We examined the cytotoxic, anti-metastatic, anti-cancer and anti-angiogenic effects of diallyl trisulfide (DATS). In HT29 cells, DATS inhibited migration and invasion through the inhibition of focal adhesion kinase (FAK), extracellular signal-regulated kinase, c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p38 which was associated with inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases-2, -7 and -9 and VEGF. In human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), DATS inhibited the migration and angiogenesis through FAK, Src and Ras. DATS also inhibited the secretion of VEGF. The capillary-like tube structure formation and migration by HUVEC was inhibited by DATS. The chicken egg chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay indicated that DATS treatment inhibited ex-vivo angiogenesis. We investigated the anti-tumour effects of DATS against human colon cancer xenografts in BALB/cnu/nu mice and its anti-angiogenic activity in vivo. In this in-vivo study, DATS also inhibited the tumour growth, tumour weight and angiogenesis (decreased the levels of haemoglobin) in HT29 cells. In conclusion, the present results suggest that the inhibition of angiogenesis may be an important mechanism in colon cancer chemotherapy by DATS.

Keywords: DATS, migration and invasion, angiogenesis, HUVEC, HT-29 human colon adenocarcinoma cells

Introduction

Cancer is one of the major causes of death in the human population 1,2. Colorectal cancer is the third ranking cancer for causing death in Taiwan based on the 2010 report of the Department of Health, R.O.C. (Taiwan). Surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy are widely used treatments of human colorectal cancer 2. To date, these treatments of human colorectal cancer are not satisfactory and the mortality in patients with advanced colorectal cancer remains high. Cancer cells invading adjacent tissues and stimulating neovascularization play an important role in tumour growth and metastasis 3,4. Tumours can stimulate the formation of new vessels; without such stimulation they cannot grow beyond 1–2 mm and cannot metastasize 5. Therefore, angiogenesis is an important determinant of tumour progression and it is also a potential target of cancer therapy 6,7. Angiogenesis is the growth of new capillaries from pre-existing capillaries and post-capillary. Tumour growth is angiogenesis-dependent and every increment of tumour growth requires an increment of vascular growth 8,9. It is well known that many diseases, including diabetes mellitus and inflammation are driven by persistent deregulated angiogenesis 10,11. Alternatively, tumour endothelial cells may divide up to 50 times more than normal endothelial cells and they will become activated through the release of pro-angiogenic growth factors including VEGF, fibroblast growth factor (FGF), the transforming growth factors (TGF-α and TGF-β), tumour necrosis factor, platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), interleukin-8, and angiopoietins from tumour and stromal cells 12,13. Angiogenesis is necessary for growth of the primary tumour as well as metastatic spread and invasion 10. It was reported that angiogenesis can be divided into two major stages: the upstream activators of VEGF synthesis and downstream signalling pathways 14. The upstream activators of VEGF synthesis include nitric oxide, H2O2, hypoxia inducible factor, oncogenes, PDGF, insulin-like growth factor 1, epidermal growth factor, bFGF and interleukin-6 which will stimulate the cancer cells to release VEGF 15–17. The VEGF will then bind and activate the VEGF receptor of endothelial cells leading to downstream signalling pathways, involving inhibition of apoptosis, degradation of the extracellular matrix and cytoskeletal changes and stimulation associated with motility 18.

Regular consumption of fruit and vegetables can reduce certain cancers 19,20. Garlic (Allium sativum), for example, has been shown to reduce deaths caused by malignant diseases 21. The major components of garlic include diallyl sulphide (DAS), diallyl disulfide (DADS) and diallyl trisulfide (DATS) and these compounds can inhibit neoplastric cell growth 22. We have demonstrated that DATS > DADS > DAS in affecting drug resistance, migration, invasion and caused cell death in human colon cancer colo 205 cells 23. DAS, DADS and DATS differ in their magnitude of effects which is related to the number of sulphur atoms in each compound 24. Although DAS and DADS have been shown to have antiangiogenic activity 25,26, effects of DATS on angiogenesis have not been reported. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine effects of DATS on angiogenesis in human colon cancer cells in vitro and in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) ex vivo.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and regents

Diallyl trisulfide was purchased from LKT Laboratories (St. Paul, MN, USA), and it was dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, USA). All antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Cell lines

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells were purchased from the Food Industry Research and Development Institute (Hsinchu, Taiwan), and cultured in 75-cm2 plastic tissue flasks then grown at 37°C under a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere in M199 medium (Invitrogen Crop., Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 20% foetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen Crop.) and 15 μg/ml endothelial cell growth supplements. Confirmation of endothelial cells was performed through the detection of CD31 (PECAM-1) by flow cytometry. The human colon adenocarcinoma cell line (HT-29) was purchased from the Food Industry Research and Development Institute. HT-29 cells were placed separately in 75 cm3 tissue culture flasks and grown at 37°C under a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen Crop.) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 Units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen Crop.).

Determination of cell viability

Approximately, 2 × 105 cells/well of HT-29 or HUVEC were maintained in 12-well plates and then were incubated without (1% DMSO vehicle control) or with 1.5625, 3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25 or 50 μM of DATS for 24 hrs. Cells from each treatment were harvested for viability determination, and harvested cells were stained with PI (5 μg/ml) and then analysed with a flow cytometer equipped with an argon ion laser at 488 nm wavelength (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) as previously described 27.

Cell migration assay

The 24-well Transwell inserts with 8 μm porosity polycarbonate filters (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA, USA) were coated with 30 μg type I collagen (Millipore) for 1 hr at room temperature to form a genuine reconstituted basement membrane. HT-29 cells (104 cells/0.4 ml medium) were placed in the upper compartment and exposed to 1.56 and 3.12 μM of DATS. Cells then were incubated at 37°C for 24 and 48 hrs. At the end of the incubation, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 2% crystal violet. The cells on the upper surface of the filter were removed by wiping with a cotton swab, and the cells that penetrated through the collagen to the lower surface of the filter were counted under a light microscope at 200× magnification 28.

Cell invasion assay

The 24-well Transwell inserts with 8 μm porosity polycarbonate filters (Millipore) were coated with 30 μg Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) at room temperature for 1 hr to form a basement membrane. HT-29 cells (104 cells/0.4 ml medium) were placed in the upper compartment and exposed to 1.56 and 3.12 μM of DATS. Cells then were incubated at 37°C for 24 and 48 hrs. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 2% crystal violet. Cells on the upper surface of the filter were removed by wiping with a cotton swab, and the cells that penetrated through the matrigel to the lower surface of the filter were counted under a light microscope at 200× magnification 29.

Determinations of VEGF secretion by ELISA

HT-29 cells (approximately, 5 × 105 cells/well) were placed in 12-well plates and treated with 0, 1.56, 3.12 and 6.25 μM of DATS for 24 hrs-incubation, after which the supernatant was collected by centrifugation. All samples were assayed for VEGF concentrations by ELISA assay kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) that were used according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Absorbance was monitored at 450 nm with a reference wavelength of 570 nm with an ELISA reader 30.

Real-time PCR of MMP-2, -7 -9 and VEGF genes levels

Total RNA was extracted from HT-29 cells after treatment with 0, or 12.5 μM of DATS for 24 or 48 hrs, using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) as previously described 31. Briefly, the RNA samples from each treatment were reverse-transcribed for 30 min. at 4°C with High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit according to the standard protocol of the supplier (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Quantitative PCR was performed with the following conditions: 2 min. at 50°C, 10 min. at 95°C, and 40 cycles of 15 sec. at 95°C, 1 min. at 60°C using 1 μl of the cDNA reverse-transcribed as described above, 2× SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and 200 nM of forward (F) and reverse (R) primers.

MMP-2-F: CCCCAGACAGGTGATCTTGAC, MMP-2-R: GCTTGCGAGGGAAGAAGTTG; MMP-7-F: GGATGGTAGCAGTCTAGGGATTAACT, MMP-7-R: AGGTTGGATACATCACTGCATTAGG; MMP-9-F: CGCTGGGCTTAGATCATTCC, MMP-9-R: AGGTTGGATACATCACTGCATTAGG; VEGF-F: CTTGCCTTGCTGCTCTACCT, VEGF-R: TGATGTTGGACTCCTCAGTGG; GAPDH-F: ACACCCACTCCTCCACCTTT, GAPDH-R: TAGCCAAATTCGTTGTCATACC.

Each assay was run on an Applied Biosystems 7300 Real-Time PCR system in triplicate and expression fold-changes were derived using the comparative CT method 28,31.

Western blotting analysis

HT-29 cells were placed in 6-well plates treated with or without 12.5 μM of DATS for 0, 6, 12, 24 and 48 hrs. HUVEC were seeded in 6-well plates and exposed to 12.5, 25 and 50 μM of DATS for 24 hrs. Cells were harvested and centrifuged, and the isolated cells were washed twice with PBS. The cells were lysed in 200 μl of the PRO-PREP protein extraction solution (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, Gyeonggi-Do, Korea) for 2 hrs. The samples were then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min. at 4°C. The supernatants were collected and the protein levels were determined by the Bio-Rad detergent-compatible protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) with bovin serum albumin (BSA) as a standard 31,32. Proteins (40 μg/lane) from each sample were individually separated on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and blotted onto polyvinyliene difluoride (PVDF, Immobilon-P Transfer Membrane, Millipore) membranes. The membranes were individually incubated with 5% BSA and primary antibodies (anti-iNOS, Cox II, uPA, Ras, RhoA, FAS, SOS, PI3K, MKK7, MEKK3, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1/2 (JNK1/2), p38, ROCK-1, Src, focal adhesion kinase (FAK), protein kinase C α (PKCα), p-ERK1/2, ERK, H-Ras, K-Ras, N-Ras) overnight at 4°C. Blots were then washed three times in PBS with 0.04% Tween-20 (PBST) for 5 min. before being incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody at 1:1000 dilutions in PBST containing 5% milk for 2 hrs at room temperature. The membranes were washed with PBST and were visualized using ECL kit (Immobilon Western HRP substrate, Millipore) and were quantified by densitometry using Image J image analysis 31,32.

Wound healing assay

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells migration was measured by using a wound-healing assay. HUVEC (1 × 105 cells/well) were placed for 24 hrs in six-well plates and at confluence a wound was made by using a pipette tip and cell debris was removed by washing with serum-free medium. Cells on the plates were then photographed under phase-contrast microscope (time = 0) and then incubated in media with or without DATS (0 and 25 μM) at 37°C and 5% CO2 and allowed to migrate into the wound area for up to 24 hrs. Cells were then gently washed with PBS, and the wound area was photographed under phase-contrast microscope 33.

Tube formation assay

Matrigel (30 μl) was pipetted into a 24-well flat bottomed plate and kept for 30 min. at 37°C. HUVEC (2 × 105 cells) were seeded into the layer of polymerized Matrigel with or without 12.5 and 25 μM of DATS and VEGF in a chamber slide (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL, USA). Matrigel cultures were incubated for 24 hrs at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. Following incubation, the tube formation was visualized, evaluated and photographed using a phase-contrast microscope (200× magnification) 34.

Chick chorioallantoic membrane assay for angiogenesis

Effects of DATS on ex vivo angiogenesis was measured by the chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay. Fertilized White Leghorn chicken eggs were incubated at 37°C under conditions of constant humidity. On embryonic day 6, the developing CAM was separated from the shell by opening a small circular window at the broad end of the egg above the air sac. The opening was sealed with Parafilm, and the eggs were incubated for two more days. DATS (6.25 μM) was prepared in PBS supplemented with 30 ng/ml of VEGF. On day 8, 20 μl was loaded onto 2-mm3 gelatin sponges (Gelfoam; Pharmacia and Upjohn Co., Donmills, Canada) that were placed on the surface of the developing CAM. Sponges containing vehicle alone (20 μl of PBS) were used as negative controls, whereas sponges containing 20 μl of 30 ng/ml of VEGF in PBS were used as positive controls. Eggs were resealed and returned to the incubator. On day 10, images of CAM were captured digitally using an Olympus SZX9 (Olympus; Tokyo, Japan) stereomicroscope equipped with a Spot RT digital imaging system (Diagnostic instruments Inc., Sterling Heights, MI, USA) 35.

BALB/cnu/nu mouse HT-29 xenograft model in vivo

Male nude mice (BALB/cnu/nu) at 6–8 weeks of age were obtained from the National Laboratory Animal Center (Taipei, Taiwan). All animals were maintained in standard vinyl cages with air filter tops in a filtered laminar air flow room at 25°C on a 12-hr light/dark cycle. Water and food were autoclaved and provided for all animals. HT-29 cells (5 × 106) in RPMI-1640 medium were subcutaneously injected into the flanks of mice. Tumour-bearing mice were then randomly divided into treatment groups (ten mice per group) and treatment initiated when the xenografted solid tumours reached a volume of about 100 mm3. Each mouse received either 100 μl of control vehicle (olive oil), or DATS (10 and 50 mg/kg) by oral administration daily beginning at day 4 and ending on day 32. All experiments were conducted according to institutional guidelines and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of China Medical University. After xenograft transplantation, mice exhibiting tumours were monitored and tumour size was measured once every 4 days using callipers. The tumour volume in each animal was estimated according to the formula: tumour volume (mm3) = L × W2/2 (where L is the length and W is the width) with the final measurement taken 4 weeks after tumour cell inoculation. Body weights of all mice were measured once every 4 days. At the end of the experiment (4 weeks after cell inoculation), animals were anaesthetized by CO2 and killed. Tumours from each animal were removed, measured and weighted 36.

Angiogenesis assay in vivo

Tumours from each animal were removed, and haemoglobin was measured as an indication of blood vessel formation using the Drabkin method (Drabkin reagent kit 525; Sigma-Aldrich) 34. The concentration of haemoglobin was calculated from a known amount of haemoglobin assayed in parallel.

Statistical analysis

Student's t-test was used to analyse differences between treatment and control groups. A statistical significance was shown as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

Results

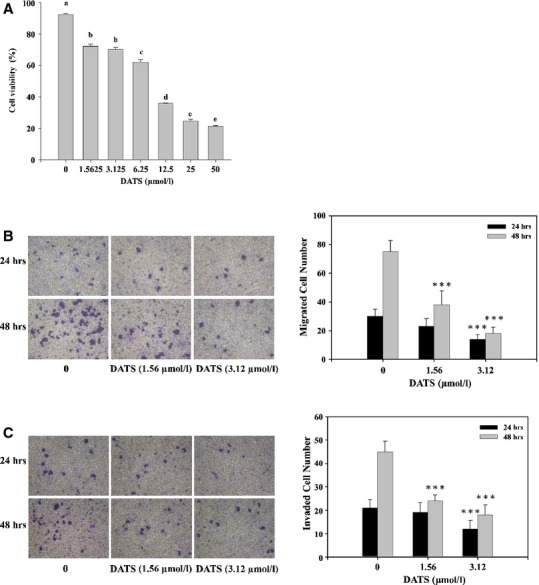

DATS inhibited the cell migration and invasion of HT-29 cells

Results from the flow cytometric assay are shown in Figure1A, which indicated that DATS-induced cytotoxic effects in HT-29 cells in a concentration-dependent manner. As shown in Figure1, there were fewer viable cells (P < 0.001) as DATS concentration increased from 1.5625 to 50 μM when compared with the control group. Next, we determined the effects of DATS treatment on migration and invasion of HT-29 cells by using a Boyden chamber assay. In control sample, a large fraction of HT-29 cells migration and invasion to the bottom face of the membrane was decreased markedly in the presence of DATS. DATS significantly inhibited the HT-29 cell migration and invasion in a time- and concentration-dependent manner (Fig.1B and C).

Fig 1.

DATS affected the percentage of viable cells and migration and invasion of HT-29 cells in vitro. Cells were placed in RPMI1640 medium + 10% FBS with different doses of DATS for 24 hrs to measure the percentages of viable cells (A). The cells were collected and analysed for viability by flow cytometry as described in Materials and methods. Cell migration was examined using Transwell inserts with polycarbonate filters (pore size, 8 μm; B). Cell invasion was examined in Transwell inserts with polycarbonate filters (pore size, 8 μm) pre-coated with matrigel (C). Figure 1A used anova analysis for Statistical analysis. Different letters (a-e) represent statistically significant difference among treatments (P < 0.05). Migration and invasion ability of HT-29 cells were quantified by counting the number of cells that invaded the underside of the porous polycarbonate membrane under microscopy and represent the average of three experiments. Figures 1B and C were used Student's t-test for control and treated group. A statistical significance was shown as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

DATS inhibited MMP-2, MMP-7, MMP-9 and VEGF secretion in HT-29 cells

We investigated the mechanisms of this cell invasive phenotype by looking at the involvement of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP)-2, -7, -9 and VEGF by Western blot and ELISA. As shown in Figure2A, DATS inhibited protein levels of MMP-2, MMP-7 and -9 in a time-dependent manner. The VEGF secretion was also reduced in HT-29 cells after treatment with DATS (Fig.2B). As shown in Figure2B, DATS-mediated secretion of VEGF was evident at 3.12 μM DATS compared to the control, and the secretion of VEGF into the medium was inhibited by 56% and 48% at a 24 hrs treatment with 3.12 and 6.25 μM DATS, respectively (Fig.2B). Real-time PCR also showed that DATS inhibited mRNA expression of MMP-2, MMP-7, MMP-9 and VEGF in HT-29 cells after a 48 hrs treatment (Fig.2C).

Fig 2.

DATS affected the level of proteins of associated migration and invasion MMP-2, -7 and -9 mRNA expressions in HT-29 cells. Cells were treated with 0, 3.12 μM of DATS for 24 and 48 hrs. The total proteins were collected and the proteins levels (MMP-2,-7 and -9) were examined by Western blot (A) as described in Materials and methods. Cells were treated with 0, 1.56, 3.12 and 6.25 μM of VEGF by ELISA assay (B) as described in Materials and methods. Cells were treated with 3.12 μM DATS then were incubated for 24 and 48 hrs. The total RNA was extracted and RNA samples were reverse-transcribed cDNA then for real-time PCR assay (C) as described in ‘Materials and methods’. The ratios of MMP-2,-7 and VEGF mRNA/GAPDH are presented. Data represent mean ± SD of three experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 were considered significantly.

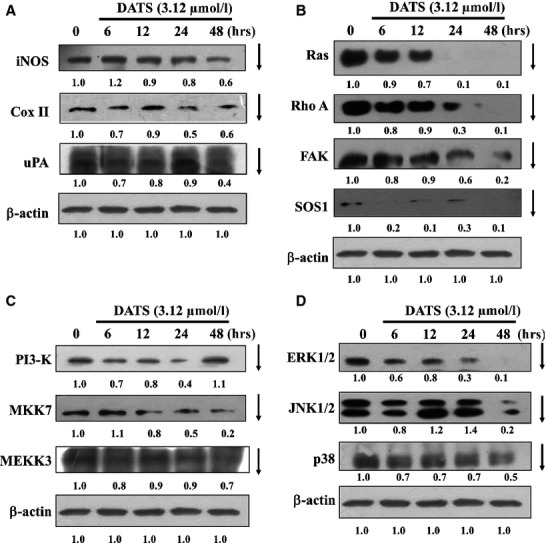

DATS affected the upstream signal of the metastasis associated proteins in HT-29 cells

To examine the possible signalling pathways for DATS inhibiting metastasis of HT-29 cells, the cells were treated with 12.5 μM of DATS for different time periods to observe changes of associated protein levels by Western blot. Results are shown in Figure3A–D. DATS-reduced proteins levels of iNOS, Cox II, uPA (Fig.3A), Ras, RhoA, FAK, SOS (Fig.3B), PI3-K, MKK7, MEKK3 (Fig.3C), ERK, JNK and p38 (Fig.3D). These results suggest that DATS down-regulated upstream signalling proteins followed by inhibition MMP-2, -7, -9 and VEGF secretion which was associated with inhibition of migration and invasion. The possible signal pathways for DATS inhibited the migration and invasion of HT-29 cells are shown in Figure4.

Fig 3.

DATS affected on the levels of up-signals proteins associated with migration and invasion in HT-29 cells. Cells were treated with 3.12 μM of DATS for 0, 6, 12, 24 and 48 hrs. The total proteins were collected and the proteins levels iNOS, COX II, uPA (A); Ras, Rho A, FAK and SOS (B); PI3-K, MKK7 and MEKK3 (C); ERK1/2, JNK1/2 and p38 (D) were examined by Western blot as described in Materials and methods.

Fig 4.

Proposed signal pathways of DATS inhibited the migration and invasion of HT-29 cells in vitro.

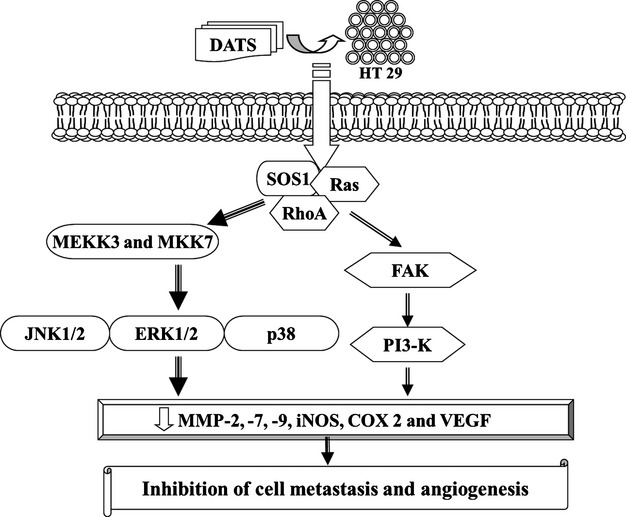

DATS-inhibited HUVEC migration

We determined effects of DATS-treated HT-29 supernatant on inhibition of HUVEC growth. Results are shown in Figure5A–C. Figure5A indicated that DATS significantly inhibited HUVEC viability in a concentration-dependent manner. To examine whether DATS affected the migratory behaviour of HUVEC, we performed a wound healing assay and a transwell migration assay. Results of the wound healing assay showed that DATS significantly inhibited HUVEC migration (Fig.5B) and as seen in Figure5C, DATS inhibited cell migration in a dose-dependent manner.

Fig 5.

DATS decreased the percentage of viable cells, and inhibited the cells migration of HUVEC. Cells were treated with the supernatant of DATS-treated HT-29 cells before HUVEC were examined for the morphological changes and the percent of viable cells (A) and the migration in vitro by wound healing examination (B) and Transwell migration assay (C) as described in Materials and methods. Data represent mean ± SD of three experiments. ***P < 0.001 was considered significant.

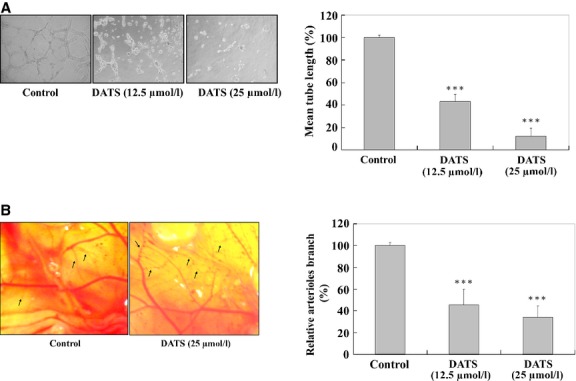

Effects of DATS on VEGF-induced tube formation in HUVEC and an in vivo CAM assay

Formation of new blood vessels requires endothelial cells to invade the extracellular matrix, raising the possibility that DATS also inhibits angiogenesis. Effects of DATS on angiogenesis ex vivo was tested using an in vitro tube formation assay and an ex vivo CAM assay. DATS (12.5 and 25 μM) of caused a concentration-dependent blockage of the capillary tubes (Fig.6A and B). Microscopic examination of the CAM revealed highly vascularized structure among tabulate of the control group (Fig.6B). In the CAM assay, angiogenesis in response to VEGF (30 ng/ml) was reduced in embryos by treatment with 25 μM of DATS (Fig.6B). Results of the CAM assay demonstrated that DATS has the ability to block VEGF-induced in vitro and in vivo angiogenesis (Fig.6A and B).

Fig 6.

DATS affected on VEGF-induced tube formation of HUVEC and an in vivoCAM assay. HUVEC (2 × 105 cells) were incubated with or without 12.5 and 25 μM of DATS and then seeded in a 96-well culture plate pre-coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and then were incubated for 24 hrs at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. After incubation, the cells morphology were evaluated by using a phase-contrast microscope and were photographed (200 × ; A). The quantitative data were determined using Image analysis software (B). On embryonic day 6 of fertilized White Leghorn chicken eggs, the developing CAM was separated from the shell by opening a small circular window at the broad end of the egg above the air sac. The eggs were incubated for two more days. Twenty-five μM DATS was prepared in PBS supplemented with 30 ng/ml of VEGF. On day 8, 20 μl was loaded onto 2-mm3 gelatin sponges as described in Materials and methods. Eggs were resealed and returned to the incubator. On day 10, images of CAM were captured digitally using an Olympus SZX9 stereomicroscope equipped with a Spot RT digital imaging system (C). The quantitative data indicated that the concentration of DATS was significantly different compared with control (D). ***P < 0.001 was considered significant.

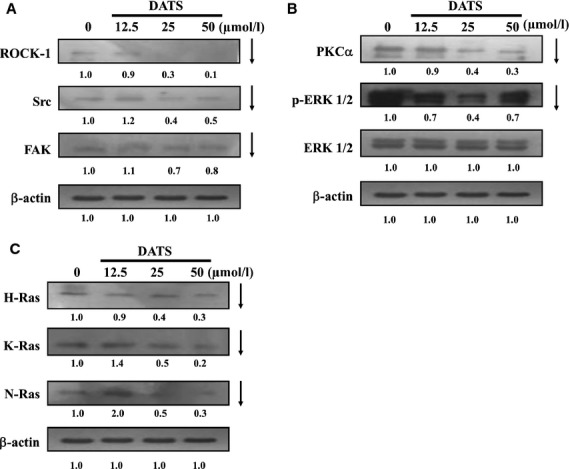

DATS affected angiogenesis associated proteins in HUVEC

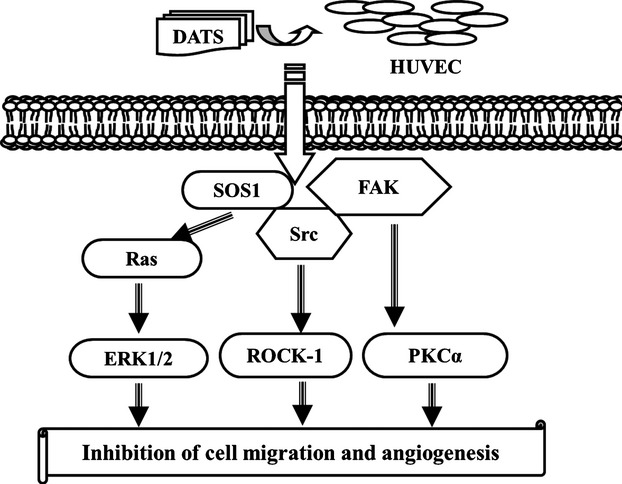

To examine the possible signalling pathways of DATS inhibition of angiogenesis in HUVEC in vitro, the cells were treated with DATS (0, 12.5, 25 and 50 μM) of for 24 hrs and in and protein levels determined by Western blots. Results are shown in Figure7A–C. DATS reduced protein levels of ROCK-1, Src, FAK (Fig.7A), PKCα, p-ERK (Fig.7B), H-Ras, K-Ras and N-Ras (Fig.7C). These results suggest that DATS down-regulated upstream signalling proteins associated with inhibition of angiogenesis. The possible signalling pathways for DATS inhibiting the angiogenesis of HUVEC are summarized in Figure8.

Fig 7.

DATS affected the upstream signal of the angiogenesis associated proteins in HUVEC. Cells were treated with 0, 12.5, 25, 50 μM of DATS for 24 hrs. The total proteins were collected and the proteins levels (A: ROCK-1, Src and FAK; B: PKCα, p-ERK1/2 and ERK; C: H-Ras, K-Ras and N-Ras) were examined by SDS-PAGE and Western blot as described in Materials and methods.

Fig 8.

Proposed signal pathways of DATS inhibited the angiogenesis associated proteins in HUVEC.

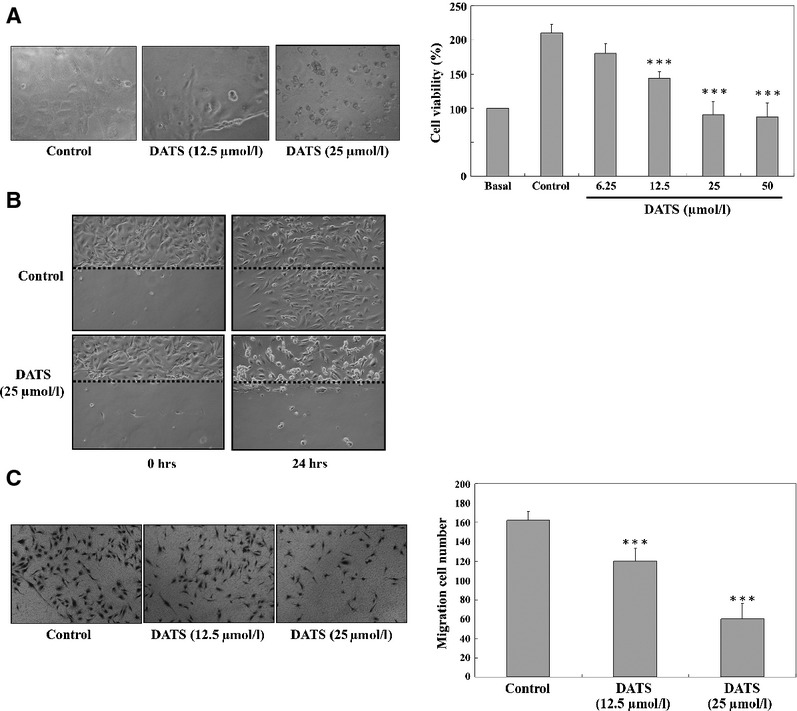

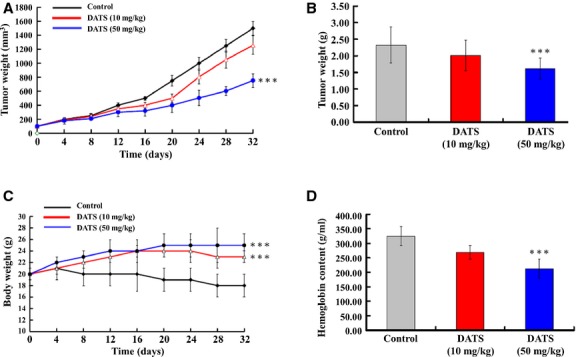

BALB/cnu/nu mouse HT-29 xenograft model in vivo

On the basis of our in-vitro studies, we further examined the in-vivo anti-colon cancer activities of DATS in a BALB/cnu/nu mouse HT-29 xenograft model. As shown in Figure9A, DATS (10 and 50 mg/kg) reduced tumour volume compared to control groups. Representative tumour weight in the HT-29 xenograft mice treated with or without DATS are shown in Figure9B; DATS significantly decreased the tumour weight compared to control groups. Body weights of the xenograft mice were not significantly changed after DATS (10 and 50 mg/kg) treatment when compared with control groups (Fig.9C). However, the control group of mice was only injected by HT-29 cells, and the body weight was decreased from day 8th to 32nd. Both DATS doses (10 and 50 mg/kg) significantly prevented the loss of body weight as compared with control group. The concentration of haemoglobin of tumour sections significantly decreased in DATS (50 mg/kg) treated-HT-29 xenograft mice as compared with the control group. Our results suggest that DATS causes anti-tumour and anti-angiogenesis activities in a HT-29 xenograft animal model in vivo.

Fig 9.

DATS affected HT29 tumour and angiogenesis in BALB/cnu/nu mouse HT29 xenograft model in vivo. HT-29 cells (5 × 106) in RPMI-1640 medium were subcutaneously injected into the flanks of BALB/cnu/nu mice. Tumour-bearing mice were then randomly divided into treatment groups (ten mice per group) and treatment initiated when the xenografted solid tumours reached a volume of about 100 mm3. Each mouse was orally receiving, every day, either 100 μl of control vehicle (olive oil), or DATS (10 and 50 mg/kg). The tumour volume in each animal was estimated according to the formula: tumour volume (mm3) = L × W2/2 (where L is the length and W is the width) with the final measurement taken 4 weeks after tumour cell inoculation (A). At the same time, the body weight of each animal was measured once every 4 days (C). At the end of the experiment (4 weeks after cell inoculation), animals were anaesthetized by CO2 and killed. Tumours from each animal were removed, measured and weighted individually (B). Tumours from each animal were removed, haemoglobin was measured as an indication of blood vessel formation, using the Drabkin method (D). The concentration of haemoglobin was calculated from a known amount of haemoglobin assayed in parallel. ***P < 0.001 was considered significant.

Discussion

Diallyl trisulfide is one of the major organosulphur compounds of garlic, and it has been recognized to have antioxidant, antiproliferative and anticarcinogenic properties 37. Studies in-vivo found that oral administration of DATS inhibited the growth, metastasis and angiogenesis of orthotopically implanted human prostate PC-3 tumours 38. Although anti-cancer effects of DATS have been demonstrated, there is no information about the effects of DATS on angiogenesis in human colon cancer cells. In this study, our results demonstrated that DATS decreased cell numbers of human colon cancer HT-29 cells and HUVEC in a dose- and time-dependent manner. DATS inhibited the migration and invasion of HT-29 cells and HUVEC. This is the first report to show that DATS reduces the growth of HT-29 cell tumour xenografts with a decrease in blood vessel density (Fig.9), suggesting that one mechanism whereby DATS decreases tumour cell proliferation is via reducing angiogenesis. Results also showed that DATS inhibited tubule formation and reduced the number of blood vessels in a CAM experiments (Fig.6). Furthermore, we found that DATS markedly reduced VEGF in both human colon HT29 cells and HUVEC, suggesting that VEGF is involved in the anti-angiogenic responses of DATS. We propose that the inhibition of angiogenesis maybe one of the major mechanisms of DATS induced cancer chemoprevention.

It is well known that metastases formation is a major factor in disease progression and accounts for the majority of cancer deaths 39,40. Recently, the invasion of tumour cells into Matrigel has been widely used for characterizing the involvement of extracellular matrix receptors and matrix degrading enzymes, in tumour progression. Our in-vitro Matrigel invasion assay demonstrated marked impairment of the invasive capability of HT29 cells after treatment with DATS. It is well known that cell migration and invasion involve many factors and to examine which of these associated factors are affected by DATS, we looked at specific protein levels. DATS reduced proteins levels of iNOS, Cox II, uPA (Fig.3A), Ras, RhoA, FAK, SOS (Fig.3B), PI3-K, MKK7, MEKK3 (Fig.3C), ERK, JNK and p38 (Fig.3D) in HT29 cells. These results suggest that DATS down-regulated upstream signalling proteins followed by reducing protein secretion of MMP-2, -7, -9 (Fig.2A) which was associated with the inhibition of migration and invasion. Furthermore, real time PCR assays also showed that DATS inhibited mRNA expression of MMP-2, -7, -9 and VEGF (Fig.2C).

Exposure of HUVEC to DATS caused suppression of VEGF secretion to the medium (Fig.2B). The precise molecular mechanism(s) for the DATS-mediated decrease in VEGF is not known. Because VEGF mRNA of HT29 cells after treatment with DATS was also reduced, DATS may activate signalling pathways to inhibit VEGF transcription. VEGF expression has been reported to be regulated at transcription by RNA stability, at translation by mRNA capping proteins, and at post-translation by glycosylation 41. VEGF was reported to be a proangiogenic growth factor most closely associated with aggressive human cancer cells 42. Therefore, the precise molecular mechanism(s) for the DATS-mediated decrease in VEGF secretion is currently under investigation.

Our results also showed that DATS reduced the protein levels of COX-II (Fig.3A) and MMP-2 and-9 (Fig.2A) in HT-29 cells. It was reported that the overexpression of COX-II is associated with the initiation of angiogenesis and COX-2 inhibitors can block angiogenesis 30. COX-2 inhibitors suppress the expression and secretion of MMP-2 and-9, suggesting that COX-2 also promotes tumour angiogenesis and tumour invasion. Furthermore, it was also reported that the downstream products of COX-2 stimulate VEGF to promote angiogenesis 30. Taken together, our studies suggest that the decrease in angiogenesis by DATS may be due to the reduction in COX-2, VEGF which leads to the inhibition of MMP-2, -7 and -9 and inhibition of migration and invasion (Fig.4).

The ability of colon cancer cells to induce angiogenesis plays an important role in tumour invasion and metastasis Development of effective therapeutic strategies for blockage of angiogenesis is required. Angiogenesis is one of the physiological processes involving the growth of new blood vessels from pre-existing vessels and it is required for tumour growth and metastasis 43. Angiogenesis is regulated by multiple factors 44 such as VEGF, FGF, and hepatocyte growth factor. It was reported that VEGF plays a key role in angiogenesis and tumour cell metastasis 45,46. VEGF is the primary proangiogenic factor released from cancer cell leading to endothelial proliferation, survival, and tube formation 47,48. Inhibition of angiogenesis is cancer treatment 49. In addition to VEGF, we also found out that DATS decreased the protein levels of PKC in HT-29 cells. VEGF mainly binds to its receptor, KDR/Flk-1, and activates MAP kinase via PKC. PKC inhibitors have been reported to inhibit angiogenesis 50. We found that DATS inhibited the growth of colon cancer in vivo in the subcutaneous xenograft model at 50 mg/kg: at this dose, DATS had a significant reducing effect on tumour growth.

Our results also showed that DATS inhibited the secretion of VEGF in HT29 cells. These observations support the hypothesis that DATS may inhibit HUVEC angiogenesis through the suppression of VEGF-mediated signalling pathways. We also found that DATS alone significantly inhibited the protein levels and gene expression mRNA levels of MMP-2, MMP-7, MMP-9 and VEGF in HT-29 cells. Based on the results of this study, we propose the signalling pathways of DATS-inhibited metastasis in HT-29 cells and DATS-inhibited angiogenesis in HUVEC which are shown in Figure6B. Taken together, our results suggest that DATS is a potent angiogenesis inhibitor with the potential to become a useful agent in the treatment of human colon cancer and other angiogenesis-dependent diseases.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the grant NSC 97-2320-B-039-017-MY3 from the National Science Council, R.O.C. (Taiwan). All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

Author contribution

KCL, SCH and CCY performed the research. SCH designed the research study. JSY and JCL analysed the data. SCH and JGC wrote the article.

References

- Jaramillo S, Lopez S, Varela LM, et al. The flavonol isorhamnetin exhibits cytotoxic effects on human colon cancer cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:10869–75. doi: 10.1021/jf102669p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nautiyal J, Banerjee S, Kanwar SS, et al. Curcumin enhances dasatinib-induced inhibition of growth and transformation of colon cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:951–61. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimeault M, Batra SK. New advances on critical implications of tumor- and metastasis-initiating cells in cancer progression, treatment resistance and disease recurrence. Histol Histopathol. 2010;25:1057–73. doi: 10.14670/hh-25.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elzer KL, Heitzman DA, Chernin MI, et al. Differential effects of serine proteases on the migration of normal and tumor cells: implications for tumor microenvironment. Integr Cancer Ther. 2008;7:282–94. doi: 10.1177/1534735408327250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkgraaf I, Boerman OC. Radionuclide imaging of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2009;24:637–47. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2009.0694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azam F, Mehta S, Harris AL. Mechanisms of resistance to antiangiogenesis therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1323–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppenberger M, Zlobec I, Baumhoer D, et al. Role of the VEGF ligand to receptor ratio in the progression of mismatch repair-proficient colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:93. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanjoormana M, Kuttan G. Antiangiogenic activity of ursolic acid. Integr Cancer Ther. 2010;9:224–35. doi: 10.1177/1534735410367647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurje G, Lenz HJ. EGFR signaling and drug discovery. Oncology. 2009;77:400–10. doi: 10.1159/000279388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgambato A, Cittadini A. Inflammation and cancer: a multifaceted link. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2010;14:263–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniyama Y, Sanada F, Morishita R. Therapeutic angiogenesis for diabetes mellitus related ischemic disease. Nippon Rinsho. 2010;68:949–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz M, Hartmann A. Angiogenesis–anti-angiogenesis. Significance for tumor growth and metastasis. Hautarzt. 2002;53:373–84. doi: 10.1007/s00105-002-0361-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpanty G, Smyth E, Sullivan LA, et al. Antiangiogenic therapy in lung cancer: focus on vascular endothelial growth factor pathway. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2010;235:3–9. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2009.009191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winder T, Lenz HJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor and epidermal growth factor signaling pathways as therapeutic targets for colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2163–76. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matrai Z, Peley G, Renyi Vamos F, et al. [The similarities between the mechanism of wound healing and tumor development–literature review on the occasion of a patient with colonic adenocarcinoma metastasis in a dog-bite wound] Orv Hetil. 2005;146:99–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan C, Shao J, Gilbert SR, et al. Role of HIF-1alpha in skeletal development. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1192:322–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05238.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer C, Soria JC. The role of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapies in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2010;11:82–90. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2010.n.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Chapuli R, Quesada AR, Angel Medina M. Angiogenesis and signal transduction in endothelial cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:2224–43. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4070-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandera EV, Kushi LH, Moore DF, et al. Fruits and vegetables and endometrial cancer risk: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Nutr Cancer. 2007;58:6–21. doi: 10.1080/01635580701307929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weikert S, Boeing H, Pischon T, et al. Fruits and vegetables and renal cell carcinoma: findings from the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC) Int J Cancer. 2006;118:3133–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao D, Zeng Y, Singh SV. Diallyl trisulfide-induced apoptosis in human cancer cells is linked to checkpoint kinase 1-mediated mitotic arrest. Mol Carcinog. 2009;48:1018–29. doi: 10.1002/mc.20553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram SG, Milner JA. Impact of organosulfur compounds in garlic on canine mammary tumor cells in culture. Cancer Lett. 1993;74:85–90. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(93)90048-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JS, Chen GW, Hsia TC, et al. Diallyl disulfide induces apoptosis in human colon cancer cell line (COLO 205) through the induction of reactive oxygen species, endoplasmic reticulum stress, caspases casade and mitochondrial-dependent pathways. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47:171–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu XJ, Hu Y, Lamy E, et al. Apoptosis induction in human lung adenocarcinoma cells by oil-soluble allyl sulfides: triggers, pathways, and modulators. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2009;50:266–75. doi: 10.1002/em.20467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thejass P, Kuttan G. Inhibition of angiogenic differentiation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells by diallyl disulfide (DADS) Life Sci. 2007;80:515–21. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thejass P, Kuttan G. Antiangiogenic activity of diallyl sulfide (DAS) Int Immunopharmacol. 2007;7:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JS, Hour MJ, Huang WW, et al. MJ-29 inhibits tubulin polymerization, induces mitotic arrest and triggers apoptosis via CDK1-mediated Bcl-2 phosphorylation in human leukemia U937 cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;334:477–88. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.165415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai KC, Huang AC, Hsu SC, et al. Benzyl isothiocyanate (BITC) inhibits migration and invasion of human colon cancer HT29 cells by inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase-2/-9 and urokinase plasminogen (uPA) through PKC and MAPK signaling pathway. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:2935–42. doi: 10.1021/jf9036694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YY, Chiang SY, Lin JG, et al. Emodin, aloe-emodin and rhein inhibit migration and invasion in human tongue cancer SCC-4 cells through the inhibition of gene expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Int J Oncol. 2010;36:1113–20. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasalandra C, Coviello M, Falco G, et al. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor and adiponectin levels in patients with benign and malignant gynecological diseases. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:507–12. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181c54fc5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang JH, Yang JS, Ma CY, et al. Danthron, an anthraquinone derivative, induces DNA damage and caspase cascades-mediated apoptosis in SNU-1 human gastric cancer cells through mitochondrial permeability transition pores and Bax-triggered pathways. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24:20–9. doi: 10.1021/tx100248s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu CC, Yang JS, Huang AC, et al. Chrysophanol induces necrosis through the production of ROS and alteration of ATP levels in J5 human liver cancer cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2010;54:967–76. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JC, Yan HC, Chen WT, et al. JNK signaling pathway is required for bFGF-mediated surface cadherin downregulation on HUVEC. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:421–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AC, Pan SL, Sun HL, et al. CHM-1, a new vascular targeting agent, induces apoptosis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells via p53-mediated death receptor 5 up-regulation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:5497–506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.036277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Pantoja DR, Menon J, Gallagher PE, et al. Angiotensin-(1-7) inhibits tumor angiogenesis in human lung cancer xenografts with a reduction in vascular endothelial growth factor. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1676–83. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tentler JJ, Bradshaw-Pierce EL, Serkova NJ, et al. Assessment of the in vivo antitumor effects of ENMD-2076, a novel multitargeted kinase inhibitor, against primary and cell line-derived human colorectal cancer xenograft models. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2989–98. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao D, Singh SV. Diallyl trisulfide, a constituent of processed garlic, inactivates Akt to trigger mitochondrial translocation of BAD and caspase-mediated apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:533–40. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar S, Chen Q, Ganapathy S, et al. Diallyl trisulfide increases the effectiveness of TRAIL and inhibits prostate cancer growth in an orthotopic model: molecular mechanisms. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2328–38. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford LJ, Vaidya KS, Welch DR. Metastasis suppressors genes in cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:874–91. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albini A, Mirisola V, Pfeffer U. Metastasis signatures: genes regulating tumor-microenvironment interactions predict metastatic behavior. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:75–83. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro RM, D'Amore PA. Transcriptional regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao D, Singh SV. Phenethyl isothiocyanate inhibits angiogenesis in vitro and ex vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2239–46. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. Angiogenesis and proteins of the hemostatic system. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:1681–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya NM, Dhalla NS, Santani DD. Angiogenesis–a new target for future therapy. Vascul Pharmacol. 2006;44:265–74. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:669–76. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh PP, Sze DM, Roufogalis BD. Molecular and cellular regulators of cancer angiogenesis. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7:743–58. doi: 10.2174/156800907783220462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor: basic science and clinical progress. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:581–611. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machein MR, Plate KH. VEGF in brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 2000;50:109–20. doi: 10.1023/a:1006416003964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. The influence of angiogenesis research on management of patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1995;36:109–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00666033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spyridopoulos I, Luedemann C, Chen D, et al. Divergence of angiogenic and vascular permeability signaling by VEGF: inhibition of protein kinase C suppresses VEGF-induced angiogenesis, but promotes VEGF-induced, NO-dependent vascular permeability. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:901–6. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000020006.89055.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]