Abstract

Background

Despite the growing prevalence of prescription opioid dependence, longitudinal studies have not examined long-term treatment response. The current study examined outcomes over 42 months in the Prescription Opioid Addiction Treatment Study (POATS).

Methods

POATS was a multi-site clinical trial lasting up to 9 months, examining different durations of buprenorphine-naloxone plus standard medical management for prescription opioid dependence, with participants randomized to receive or not receive additional opioid drug counseling. A subset of participants (N=375 of 653) enrolled in a follow-up study. Telephone interviews were administered approximately 18, 30, and 42 months after main-trial enrollment. Comparison of baseline characteristics by follow-up participation suggested few differences.

Results

At Month 42, much improvement was seen: 31.7% were abstinent from opioids and not on agonist therapy; 29.4% were receiving opioid agonist therapy, but met no symptom criteria for current opioid dependence; 7.5% were using illicit opioids while on agonist therapy; and the remaining 31.4% were using opioids without agonist therapy. Participants reporting a lifetime history of heroin use at baseline were more likely to meet DSM-IV criteria for opioid dependence at Month 42 (OR=4.56, 95% CI=1.29-16.04, p<.05). Engagement in agonist therapy was associated with a greater likelihood of illicit-opioid abstinence. Eight percent (n=27/338) used heroin for the first time during follow-up; 10.1% reported first-time injection heroin use.

Conclusions

Long-term outcomes for those dependent on prescription opioids demonstrated clear improvement from baseline. However, a subset exhibited a worsening course, by initiating heroin use and/or injection opioid use.

Keywords: Opioids, prescription opioids, addiction, treatment, follow-up, heroin

1. INTRODUCTION

Despite the high rate of prescription opioid abuse and dependence in the U.S. (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2012), little research has been published on the treatment of patients dependent upon prescription opioids. Moreover, no follow-up studies to date have examined long-term response to treatment and course of illness in this population. Virtually all studies of the long-term course of opioid dependence examine heroin users (Darke et al., 2007; Flynn et al., 2003; Grella and Lovinger, 2011; Hser et al., 2001; Vaillant, 1973). However, as emerging data suggest that outcomes for those dependent upon prescription opioids may differ from those using heroin (Moore et al., 2007; Nielsen et al., 2013; Potter et al., 2010), we cannot assume that results from longer-term studies of heroin dependence apply to those abusing prescription opioids.

Longitudinal follow-up of substance-dependent patients generates important information regarding treatment response and course of illness. In particular, studies have shown that longer-term outcomes and predictors of outcome (Brecht and Herbeck, 2014; Grella et al., 2003; Project MATCH research group, 1998) at 3-5 years can differ from those found at shorter-term follow-up. This is consistent with viewing substance use disorder as a chronic disease with a course that spans years rather than a single episode (McLellan et al., 2000).

The Prescription Opioid Addiction Treatment Study (POATS), conducted by the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network, is, to date, the only large randomized controlled study examining the treatment of patients dependent upon prescription opioids with a history of minimal or no heroin use (Weiss et al., 2011). POATS compared different combinations of buprenorphine-naloxone (bup-nx) and counseling in this population. As the first large-scale controlled trial for prescription opioid dependence, POATS presented a unique opportunity to follow this patient population beyond the treatment period. Therefore, during the main trial, we decided to extend the assessment period to follow POATS participants 18, 30, and 42 months after randomization in the main trial. We previously reported results from the 18-month follow-up (Potter et al., 2014); the current paper extends this work to present results from the entire 42-month POATS follow-up study. The aim of this exploratory study was to examine the course of opioid use and related outcomes post-treatment and their relationship to baseline characteristics, treatment response in the main POATS trial, and current treatment.

2. METHODS

2.1. Description of the main POATS trial and outcomes

POATS was conducted from 2006-2009 at 10 sites from the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (Weiss et al., 2011). Briefly, individuals >age 18 who met DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for current opioid dependence (i.e., not physical dependence alone) were eligible unless they used heroin on >4 of the past 30 days, had a lifetime opioid dependence diagnosis due to heroin alone, had ever injected heroin, required opioids for ongoing pain management, were psychiatrically unstable, required urgent medical treatment for other substance dependence, had liver function tests >5 times normal, or were pregnant or nursing.

Using a two-phase, adaptive treatment design, participants were randomized in each phase to either standard medical management (SMM) or SMM plus individual opioid drug counseling (ODC), to investigate whether adding counseling to bup-nx and SMM led to better opioid use outcomes. Originally, SMM was designed to approximate office-based opioid dependence treatment in primary care (Fiellin et al., 1999). SMM consisted of brief visits with a physician, combining buprenorphine-naloxone administration with medically-focused counseling. This included reviewing substance use and treatment adherence; encouraging abstinence, self-help group participation, and a healthy lifestyle; asking about opioid craving and pain; and offering referrals as needed. ODC (Mercer and Woody, 1999; Pantalon et al., 1999) focused more extensively on relapse prevention issues, skill-building, and lifestyle change, while offering education on addiction and recovery and reinforcing the importance of abstinence and the benefits of self-help groups; these sessions lasted 45-60 minutes.

All participants received bup-nx and weekly SMM. In the first phase (“brief treatment”), participants received a 4-week bup-nx taper and were followed for 8 additional weeks; only 7% of participants had successful opioid use outcomes (abstinence or near-abstinence) in this phase. In the second phase (“extended treatment”), offered to participants who relapsed to opioid use during or soon after the initial taper, participants were stabilized on bup-nx for 12 weeks; the primary study outcome measure was “success:” self-reported, urine-confirmed opioid abstinence in week 12 of bup-nx stabilization and at least 2 of the previous 3 weeks (weeks 9-11). Forty-nine percent of participants had successful outcomes in extended treatment. Adding ODC (twice weekly in brief treatment; twice weekly for six weeks, then once a week for six weeks in extended treatment) to bup-nx and SMM did not improve outcomes. Secondary analyses suggested that outcomes did not vary by chronic pain, whereas even minimal lifetime heroin use (heavy heroin users were excluded) was associated with poorer outcomes. Participants were tapered off bup-nx over the next four weeks and were then followed for 8 weeks, with no more study contact until December 2008 (when the follow-up study was approved), when they were offered the opportunity to participate in the follow-up study.

2.2. Follow-up study procedures

Although not part of the original POATS protocol, long-term follow-up was added due to the unique nature of the study sample. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for the follow-up extension from each site. Participants provided written informed consent at their local site, and additional telephone oral consent with a lead team staff member. Telephone interviews were conducted by trained research assistants at the lead site (McLean Hospital) between March, 2009 and January, 2013. Targets for assessment dates were 18, 30, and 42 months after participants entered the first phase of the study. To maximize the opportunity to obtain data, assessments could occur from one month prior to the target assessment date until one month prior to the following assessment date. Assessments covered the past 12 months and lasted 45-60 minutes. Participants received $75 for each assessment, similar to other SUD treatment studies (Festinger et al., 2005); participants also received $5 per quarterly contact update, and $10 to keep the first scheduled assessment. A $25 bonus was offered as an additional incentive for participants at risk to miss their target date.

2.3. Follow-up study measures

Follow-up interviews consisted of a subset of questionnaires from the main POATS trial (Weiss et al., 2011 for details), supplemented by items to assess the participants' subsequent course of substance use and treatments received. The following measures were administered at all three follow-up points.

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Section L (World Health Organization, 1997) was used to diagnose opioid dependence. In this report, we distinguish between those with “current opioid dependence” (meeting current DSM-IV criteria for the disorder) and those with “opioid dependence on agonist therapy.” The latter category, according to DSM-IV, describes individuals on agonist therapy, with no DSM-IV symptoms of current opioid dependence (other than tolerance and withdrawal). Unless specified otherwise, “current opioid dependence” refers to participants’ meeting current symptomatic criteria.

Substance use at follow-up was assessed with drug and alcohol use items from the Addiction Severity Index (McLellan et al., 1992). Four items assessing overall health and pain were retained from the Medical Outcome Study Short Form-36 (Ware and Sherbourne, 1992). The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence measured severity of dependence among smokers (Heatherton et al., 1991). Substance use and treatment for SUD, pain, and mental health problems during the past year were assessed with questionnaires designed for the follow-up study. A subset of items from the Pain and Opiate Analgesic Use History (Weiss et al., 2010b) was retained.

In the absence of a generally accepted method to reliably distinguish opioid use as prescribed from illicit use, and our reliance on self-report, we did not attempt to distinguish these types of opioid use from each other (the only exception occurred when participants reported being prescribed buprenorphine or methadone to treat opioid dependence itself). This decision rule was consistent with our inclusion criteria and procedures during the main trial; patients who had been prescribed opioids for pain prior to the main trial had to receive permission from their prescribing physician to discontinue opioids and enter the study. Thus, the study sample reflected a group for which opioid management of pain was not considered the indicated treatment, at least at study entry.

2.4. Statistical analysis

In this exploratory analysis, we examined changes over time in opioid use, related clinical outcomes, and treatment utilization, as well as predictors of outcomes at 42-month follow-up. Bivariate associations were assessed with chi-square tests for categorical variables and two-tailed independent t-tests for continuous variables. For analyses examining longitudinal change in binary outcomes, marginal regression models were estimated using the generalized estimating equations (GEE) approach. These models are a natural extension of generalized linear models (e.g., logistic regression) to the longitudinal setting; GEE allows all available repeated measures per subject to be incorporated in the analysis while appropriately accounting for the positive correlation among repeated assessments. Mixed effects models were used in analysis of longitudinal change in continuous outcomes. All longitudinal models were adjusted for initial treatment condition; to account for potential clustering of data within study sites, these models also included site as fixed effects via inclusion of an indicator, or dummy variable, for each site. Models examining methadone maintenance and inpatient treatment as binary dependent variables did not adjust for site due to low prevalence of these outcomes. Adjusting the longitudinal models for gender and race did not alter the results. Multivariable models examined predictors of 42-month status, including the sociodemographic, clinical, and treatment study characteristics shown in Table 1 (only redundant characteristics were excluded); these models were adjusted for initial treatment condition and site. All analyses used SPSS v.20 (IBM Corporation, 2011).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of POATS participants by enrollment in the follow-up study (N=653)

| Follow-up study participation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | Yes (375) | No (278) |

| Sociodemographics | ||

| Female sex, % | 43.5 | 35.3* |

| Age, mean (sd) | 33.0 (9.6) | 33.5 (10.9) |

| White race, % | 89.9 | 93.5 |

| Never married, % | 48.0 | 52.5 |

| Employed full-time, % | 64.5 | 60.8 |

| Years education, mean (sd) | 13.0 (2.1) | 13.1 (2.3) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Substance use | ||

| Non-opioid substance dependence diagnoses, % | ||

| Alcohol, past year | 3.7 | 4.0 |

| Lifetime | 28.0 | 24.5 |

| Cannabis, past year | 5.9 | 4.3 |

| Lifetime | 17.1 | 13.3 |

| Cocaine, past year | 3.2 | 3.6 |

| Lifetime | 17.9 | 18.3 |

| Other stimulants, past year | 3.5 | 0** |

| Lifetime | 13.1 | 7.9* |

| Sedative-hypnotics, non-barbiturates, past year | 4.8 | 7.9 |

| Lifetime | 9.6 | 10.4 |

| None, past year | 84.3 | 84.2 |

| Lifetime | 52.5 | 52.9 |

| Opioid use history | ||

| Ever used heroin, % | 21.6 | 24.8 |

| Years opioid use, mean (sd) | 5.3 (4.6) | 5.1 (4.1) |

| Previous opioid use disorder treatment, % | 32.3 | 29.1 |

| First used opioids to relieve pain, % | 62.7 | 64.0 |

| Used extended-release oxycodone most, past 30 days, % | 35.2 | 35.3 |

| Route other than swallowing/sublingually, % | 77.9 | 77.0 |

| Tobacco dependence severity, mean (sd) | 3.3 (2.9) | 3.2 (2.9) |

| Other psychiatric | ||

| Major depressive disorder, past year, % | 21.3 | 21.9 |

| Lifetime, % | 34.7 | 34.5 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder, past year, % | 11.5 | 12.9 |

| Lifetime, %, n=647 | 15.9 | 21.5 |

| Beck Depression Inventory, mean (sd) | 22.1 (12.1) | 22.4 (11.5) |

| Study characteristics, % | ||

| Standard Medical Management-only initial treatment | 52.3 | 46.0 |

p<0.05

p<0.01

3. RESULTS

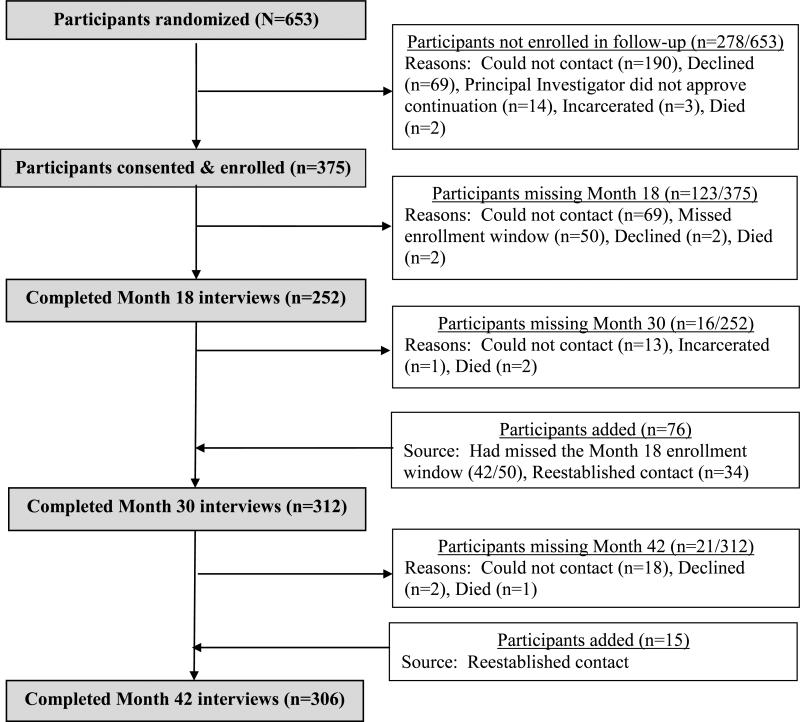

Among the 653 POATS participants, 375 (57%) enrolled in the follow-up study (Figure 1). The number of participants completing each follow-up assessment was 252 for Month 18 (67% of the follow-up sample; 39% of the entire study sample), 312 for Month 30 (83% of the follow-up sample; 48% of the study sample), and 306 for Month 42 (82% of the follow-up sample; 47% of the study sample). We conducted the fewest Month 18 assessments in part due to logistics: 50 participants enrolled in the follow-up study after their 18-month assessment window had passed.

Figure 1.

Participant flow in the POATS follow-up study

Retention within the follow-up study was high. Of the 252 participants who completed a Month 18 interview, 236 (94%) completed Month 30; of the 312 participants who completed a Month 30 interview, 291 (93%) completed Month 42. Five participants died during the follow-up period; causes of death were not determined.

3.1. Characteristics of follow-up participants vs. non-participants

POATS participants who enrolled in the follow-up study were more likely than those who did not enroll to be female (Table 1) and to have lifetime and past-year stimulant dependence at baseline, although stimulant dependence was uncommon (<5%). There were no statistically significant differences between follow-up participants and non-participants on any other baseline sociodemographic or clinical characteristics.

A comparison of follow-up participants and non-participants on post-baseline characteristics found no significant difference in rates of successful outcomes during brief treatment (7.5% vs. 5.4%, respectively) or extended treatment (49.4% vs. 48.6%). Follow-up participants were more likely to have entered the extended treatment phase than were non-follow-up participants (67.5% vs. 38.5%; χ2(1)=54.19, p< 0.001). Because only 338 of the 375 participants who enrolled in the follow-up study actually completed any follow-up assessments, we also compared baseline characteristics for these 338 to the 315 main-trial participants who completed no follow-up assessments; no new differences emerged.

Because participants who entered POATS during the initial months of the study had not been in contact with study personnel for up to 2.5 years, we posited that early participants in the main trial may have been less likely to participate in the follow-up study. As reported earlier (Potter et al., 2014), this was the case; those who did not participate in the follow-up were more likely to have participated earlier in the course of the POATS trial. The length of time between completion of the treatment study and the launch of the follow-up study was nearly double for non-participants (mean=14.1 (sd=7.5) vs. 7.5 months (sd=5.8), t(622.1)=12.54, p<.001).

3.2. Opioid use and related outcomes: Changes over time from baseline to Month 42

At entry to the treatment trial, all participants met DSM-IV criteria for dependence on prescription opioids; none were receiving opioid agonist therapy. At Month 42 follow-up, much improvement was seen: 31.7% (n=97) were abstinent from opioids and not on opioid agonist therapy; 29.4% (n=90) were receiving agonist therapy but abstained from other opioids (i.e., they met DSM-IV criteria for opioid dependence on agonist therapy; see Section 2.3); 7.5% (n=23) were using illicit opioids while on agonist therapy; and the remaining 31.4% (n=96) were using opioids without agonist therapy.

Longitudinal models present the three primary, discrete outcome variables: 1) opioid dependence, excluding those with a diagnosis of opioid dependence on agonist therapy; 2) abstinence from illicit opioids; and 3) opioid agonist therapy. Other substance use, health, and chronic pain outcomes were also compared from study entry across the three follow-up assessments (Table 2). Participants improved in a number of clinical characteristics from baseline (at which heavy current opioid use and opioid dependence were required for eligibility) to Month 18; overall, these gains were maintained or enhanced over the course of the 30-month and 42-month follow-up assessments. For example (see 1st row, Table 2), although all participants (100%) were opioid dependent at baseline, the majority (100-16.3=83.7%) of the follow-up sample was no longer opioid dependent (excluding those with a diagnosis of opioid dependence on agonist therapy; see Section 2.3) in the previous month at Month 18; longitudinal analysis indicated that the rate of past-month opioid dependence was stable from Month 18 to Month 30 (16.3% to 11.5%), then declined at Month 42 (to 7.8%). Examination of opioid dependence (excluding those with a diagnosis of opioid dependence on agonist therapy) over the past year also declined, with a rate of 32.4% at Month 42. Similar trends were observed for abstinence and mean days of past-month opioid use. Nearly half of the follow-up participants were abstinent from illicit opioids (i.e., abstinent from all opioids or receiving agonist therapy with no other opioid use) at Month 18; longitudinal analysis showed that these numbers increased significantly from Month 18 to Month 30, then were stable from Month 30 to Month 42. Mean days of past-month illicit opioid use significantly decreased from near-daily use at baseline to one out of 3 days at Month 18 and one out of 4 days at Month 42.

Table 2.

Change in clinical characteristics from study entry to follow-up 18, 30, and 42 months later

| Participant characteristics | Month 01 (n=338) | Month 18 (n=252) | Month 30 (n=312) | Month 42 (n=306) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substance use, past month | ||||

| Current opioid dependence2, %*** | 100 | 16.3a | 11.5 | 7.8b |

| Abstinent from illicit opioids3, %*** | 0 | 51.2a | 63.5b | 61.4b |

| Opioid agonist treatment, % | 0 | 31.8 | 38.1 | 36.9 |

| Days of illicit substance use, mean (sd) | ||||

| Prescription opioids3*** | 27.9 (3.2)a | 10.2 (12.8)b | 7.0 (11.4)c | 6.8 (11.3)c |

| Heroin*** | 0.1 (0.5)a | 0.5 (2.8)b | 0.9 (4.3)b | 0.8 (4.4)b |

| Alcohol* | 2.9 (6.1)a | 2.5 (5.5)a,b | 2.1 (4.9)b | 2.3 (5.5)a,b |

| Cannabis*** | 5.3 (10.0)a | 3.1 (7.5)b | 2.7 (7.0)b | 2.5 (6.7)b |

| Cocaine*** | 0.5 (2.3)a | 0.2 (1.0)b | 0.2 (1.8)b | 0.1 (0.7)b |

| Other stimulants | 0.7 (3.6) | 1.0 (4.8) | 1.0 (5.0) | 1.3 (5.4) |

| Sedative-hypnotics, non-barbiturate | 3.6 (7.7) | 3.6 (8.3) | 3.7 (8.9) | 3.9 (8.9) |

| >1 drug*** | 10.7 (11.4)a | 7.2 (10.4)b | 6.9 (10.6)b | 6.4 (10.2)b |

| Perceived health4, mean (sd) | ||||

| General health | 2.9 (0.8) | 2.8 (1.0) | 2.7 (1.0) | 2.8 (1.0) |

| General health compared to 1 year ago*** | 3.3 (0.8)a | 2.3 (1.2)b | 2.3 (1.1)b | 2.5 (1.1)c |

| Chronic pain | ||||

| Prevalence, %*** | 42.6a | 34.1b | 28.2b,c | 26.1c |

| Intensity, mean (sd)5*** | 4.0 (0.9)a | 3.6 (1.3)b | 3.5 (1.2)b | 3.5 (1.3)b |

| Interference with normal work, mean (sd)5*** | 2.8 (1.0)a | 2.4 (1.3)b | 2.4 (1.2)b | 2.3 (1.3)b |

Month 0= Initial randomization to treatment study, i.e., study entry

Excludes those diagnosed with opioid dependence on opioid agonist therapy (25.4% at Month 18, 32.1% at Month 30, and 29.4% at Month 42 were excluded)

Those whose opioid use is limited to taking agonist treatment as prescribed are considered abstinent from illicit opioids (25.4% at Month 18, 32.1% at Month 30, and 29.4% at Month 42 were included).

Higher numbers indicate worse perceptions of health.

Based on n=144 with chronic pain at main-trial entry

p<.05

**p<.02

p<.001

Different alphabetical superscripts in a row indicate change significant at p<.05.

Substance use other than prescription opioids evidenced small but significant declines in some substances, primarily from baseline to Month 18 (i.e., alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, and polydrug use). No significant change over time was seen in use of non-barbiturate sedativehypnotics or non-cocaine stimulants. The only exception was heroin use, which increased from baseline to Month 18, then remained stable (Section 3.3). Notably, as in the main trial, all of these substances were used infrequently.

Perception of change in general health over the past year improved over time, with the greatest gain from baseline to Month 18. The prevalence of chronic pain (self-reported “other than every day kinds of pains,” not related to withdrawal, for ≥3 months) decreased steadily over time. Among those with chronic pain at baseline, pain intensity and interference with work both improved significantly from baseline to Month 18, with gains retained throughout follow-up.

3.3. Heroin use over time

Among the 266 participants who denied ever using heroin before entering POATS, 10.2% (n=27) reported heroin use after study entry, all by the Month 30 assessment. Although heroin use for >4 days during the past month was an exclusion criterion in the main trial, 34.6% of heroin users reported this level of use at Month 18, 41.0% at Month 30, and 41.4% at Month 42. Conversely, two-thirds of participants who reported lifetime heroin use at baseline did not report heroin use in the follow-up period (66.7% of 72 lifetime users). Although a lifetime history of heroin injection was an exclusion criterion for POATS, 34 participants (10.1% of the follow-up sample) reported for the first time at a follow-up assessment injecting heroin intravenously >5 times during the past year.

3.4. Utilization of SUD treatment

Nearly two-thirds of the 338 follow-up participants continued in some SUD treatment after the main trial ended, ranging between 61-66% at the three follow-up assessments (treatment received in POATS ended by the conclusion of the main trial; thus, treatments reported during follow-up were not study-related). The most common treatment was buprenorphine maintenance, which was equally common across all follow-up visits (41-43%; no significant change). The use of medications other than buprenorphine was less common, with 6-9% of participants receiving methadone maintenance (no significant change) and 0-1% using other SUD medications (naltrexone and disulfiram) during follow-up. Treatments that were frequently utilized and declined over time were self-help groups (from 41% down to 35%; p<.02) and outpatient counseling (from 32% down to 23%; p<.002). Less frequently used treatments included medical detoxification (from 12% down to 6%; p<.005), inpatient/residential treatment (3-7%; no significant change), and intensive outpatient/day hospital treatment (2-3%).

3.5. Factors associated with 42-month outcomes

3.5.1. Baseline predictors of 42-month outcomes

Most baseline characteristics were not associated with Month 42 outcomes in bivariate analyses (Table 3). However, participants who met symptomatic criteria for opioid dependence at Month 42 were more likely to report lifetime heroin use at baseline (41.7%) than were participants who did not meet criteria for opioid dependence (19.9%). Additionally, the likelihood of receiving opioid agonist therapy at Month 42 varied: participants with more severe depressive symptoms at baseline were more likely than those with fewer depressive symptoms to be enrolled in opioid agonist therapy. Participants who had used extended-release oxycodone more than any other prescription opioid in the 30 days preceding study entry were less likely to be enrolled in opioid agonist therapy at Month 42 than were participants with another primary prescription opioid.

Table 3.

Associations between characteristics at study entry and Month 42 status (N=306 who participated in the Month 42 assessment)

| Month 42 abstinent from illicit opioids, past 30 days | Month 42 opioid dependence, past 30 days | Month 42 opioid agonist therapy, past 30 days | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics at study entry1 | Abstinent2 (61.4%) | Not (38.6%) | Dependence3 (7.8%) | Not (92.2%) | On opioid agonist therapy (36.9%) | Not (63.1%) |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Female sex, % | 46.8 | 43.2 | 41.7 | 45.7 | 51.3 | 42.0 |

| Age, mean (sd) | 32.5 (9.6) | 34.1 (10.2) | 32.4 (9.6) | 33.2 (9.9) | 33.6 (9.7) | 32.8 (10.0) |

| White race, % | 90.4 | 91.5 | 91.7 | 90.8 | 90.3 | 91.2 |

| Years education, mean years (sd) | 13.0 (2.1) | 13.1 (2.0) | 13.1 (1.8) | 13.0 (2.1) | 13.0 (1.9) | 13.1 (2.1) |

| Never married, % | 51.6 | 46.6 | 45.8 | 50.0 | 46.0 | 51.8 |

| Employed full-time, % | 63.8 | 65.3 | 75.0 | 63.5 | 61.1 | 66.3 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Tobacco smoker, % | 75.0 | 71.2 | 79.2 | 73.0 | 75.2 | 72.5 |

| Tobacco dependence severity, mean (sd) | 3.2 (2.9) | 3.1 (2.8) | 3.5 (2.9) | 3.1 (2.9) | 3.2 (2.9) | 3.1 (2.8) |

| Non-opioid substance dependence diagnoses, % | ||||||

| Past year | 15.4 | 19.5 | 25.0 | 16.3 | 16.8 | 17.1 |

| Lifetime | 45.2 | 49.2 | 54.2 | 46.1 | 46.0 | 47.2 |

| Opioid use history, % | ||||||

| Ever used heroin | 19.1 | 25.4 | 41.7 | 19.9* | 22.1 | 21.2 |

| Opioid use ≥4 years, n=305 | 48.4 | 47.9 | 50.0 | 48.0 | 49.6 | 47.4 |

| Previous opioid use disorder treatment | 30.9 | 39.8 | 33.3 | 34.4 | 35.4 | 33.7 |

| First used opioids to relieve pain | 64.4 | 58.5 | 54.2 | 62.8 | 63.7 | 61.1 |

| Used extended-release oxycodone most, past 30 days | 33.0 | 40.7 | 45.8 | 35.1 | 24.8 | 42.5** |

| Route other than swallowing/sublingually | 81.4 | 83.9 | 83.3 | 82.3 | 80.5 | 83.4 |

| Chronic pain | ||||||

| Prevalence, % | 42.6 | 41.5 | 37.5 | 42.6 | 45.1 | 40.4 |

| Severity (SF-36), mean (sd)4 | 4.0 (1.0) | 4.0 (0.8) | 3.9 (1.1) | 4.0 (0.9) | 4.0 (0.8) | 4.0 (1.0) |

| Interference with normal work (SF-36), mean (sd)4 | 2.8 (1.0) | 2.8 (1.0) | 3.0 (0.7) | 2.8 (1.0) | 3.0 (1.0) | 2.7 (1.0) |

| Other psychiatric | ||||||

| Major depressive disorder, % | ||||||

| Past year | 20.7 | 23.7 | 20.8 | 22.0 | 22.1 | 21.8 |

| Lifetime | 37.2 | 35.6 | 29.2 | 37.2 | 40.7 | 34.2 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder, % | ||||||

| Past year | 12.8 | 11.9 | 20.8 | 11.7 | 15.9 | 10.4 |

| Lifetime, N=303 | 15.7 | 16.9 | 25.0 | 15.4 | 18.9 | 14.6 |

| Beck Depression Inventory, mean (sd) | 23.0 (11.9) | 21.7 (12.6) | 22.4 (14.4) | 22.5 (12.0) | 25.2 (10.8) | 21.0 (12.7)** |

Study entry = Initial randomization to treatment study

Those whose opioid use is limited to taking agonist treatment as prescribed are considered abstinent from illicit opioids (29.4% included).

Excludes those diagnosed with opioid dependence on agonist therapy (29.4% excluded)

Based on n=129 with chronic pain at main-trial entry

p<.05

p<.01

Since bivariate results involve many potentially overlapping comparisons, multivariable models were examined. Results from these models (one for each dependent variable in Table 3) were identical to the bivariate analyses. Those who had used heroin before study entry remained more likely to be opioid dependent at Month 42 (OR=3.58, 95% CI=1.06-12.05, p<.05). Those with more severe depressive symptoms (OR=1.20, 95% CI=1.05-1.36, p<.01) and those reporting a primary prescription opioid other than extended-release oxycodone (OR=2.0, 95% CI=1.02-3.86, p<.05) were more likely to enroll in opioid agonist therapy at Month 42, consistent with the bivariate associations. No baseline characteristics were associated with abstinence from illicit opioids at Month 42. Initial treatment condition (i.e., SMM alone or SMM plus ODC) was not associated with any of the Month 42 outcomes.

3.5.2. Main-trial outcomes as predictors of 42-month outcomes

We examined the association between main-trial treatment response and Month 42 status. Participation in extended treatment was not associated with past-month abstinence from illicit opioids or opioid dependence at Month 42. Unlike our results at Month 18 (Potter et al., 2014), successful outcomes in neither brief treatment nor extended treatment were associated with abstinence or opioid dependence at Month 42.

Those who participated in extended treatment were more likely than those who only participated in brief treatment to be enrolled in opioid agonist therapy at Month 42 (40.7% vs. 28.3%, χ2(1)=4.24, p<.05). Moreover, those who had successful outcomes in extended treatment were more likely than those who were unsuccessful to be enrolled in agonist therapy at Month 42 (54.3% vs. 27.5%, χ2(1)=15.88, p<.001). The few participants with successful outcomes after a brief bup-nx taper were less likely to be enrolled in agonist therapy at Month 42, compared to those who were unsuccessful in brief treatment (17.4% vs. 38.5%, χ2(1)=4.08, p<.05). 3.5.3. The relationship between bup-nx treatment and Month-42 opioid use. Because the main treatment trial showed a strong relationship between bup-nx treatment and successful outcome (Weiss et al., 2011), we examined this relationship at Month 42, and found that engagement in agonist therapy was significantly associated with abstinence at Month 42; most participants receiving agonist therapy at Month 42 (90/113, 79.6%) were abstinent from other opioids in the past month, compared to half (98/193, 50.8%) of those not receiving agonist therapy (χ2(1)=25.1, p<.001).

4. DISCUSSION

This 3.5-year follow-up of prescription opioid dependent patients participating in a clinical trial showed marked improvement: use of illicit opioids and other substances declined substantially from study entry. For example, although all trial participants had a DSM-IV diagnosis of opioid dependence at baseline, only 7.8% of those in the follow-up sample met current criteria for opioid dependence at Month 42, whereas another 29.4% met criteria for opioid dependence on agonist therapy. Past-year opioid dependence, however, was considerably higher at Month 42 (32.4%) than past-month dependence rates at any of the three past-month assessments, reflecting intermittent periods of use. Approximately half of the participants abstained from illicit opioids in the month prior to 18-month follow-up; this number rose to >60% at Month 42. Moreover, participants reported improvement in general health and pain, possibly associated with these positive changes in substance use.

Participants engaging in opioid agonist therapy continued to have better outcomes, as in the main trial and 18-month follow-up, consistent with studies of heroin dependence (Gowing et al., 2009). However, the rate of abstinence from opioids among participants not receiving agonist therapy was approximately 50% at Month 42, in contrast with abstinence rates of <10% in the main trial among participants who had been tapered from bup-nx. Moreover, unlike in long-term studies of heroin dependence (e.g., Grella and Lovinger, 2011; Hser et al., 2001), this sample did not increase use of other substances concurrent with decreased opioid use. A lifetime history of heroin use at baseline remained a poor prognostic factor through Month 42, despite the exclusion of those with regular heroin use from the trial (Weiss et al., 2010a). Although a successful treatment response in either phase of the main trial predicted abstinence from illicit opioids at Month 18 (Potter et al., 2014), this relationship was no longer statistically significant by Month 42.

Despite generally positive results, some participants became involved with heroin. Consistent with concerns about the possible transition from prescription opioids to heroin (Cicero et al., 2014; Jones, 2013), approximately 10% of participants reported using heroin for the first time during follow-up. Moreover, many of those using heroin during follow-up used more often than permitted for entry into the main trial (>4 days in the past month). Concomitantly, many former heroin users abstained from heroin during the follow-up period. Injection use of heroin is also concerning; 10% of the follow-up population (n=34) reported injecting heroin intravenously >5 times in the previous year. Because people who had ever injected heroin were excluded from the main trial, this reflects new use. Indeed, mortality is a risk of this disorder (Calcaterra et al., 2013) as reflected by the death of 5 participants in the follow-up sample.

Finally, these findings illustrate the importance of conducting longer-term follow-up studies. Main-trial results demonstrated nearly universal relapse to opioid use following a bup-nx taper; 49% were successful while subsequently stabilized on bup-nx. In contrast, among participants completing the Month 42 follow-up, half reported abstinence from opioids without agonist therapy, and >75% receiving agonist therapy reported abstinence from other opioids. Although this may reflect selection bias associated with the follow-up sample, it also suggests that poor short-term treatment outcomes do not necessarily portend similar long-term results.

4.1. Limitations

This follow-up study has several limitations. First, follow-up assessments were completed by 52% of randomized main-trial participants; hence, our findings may not be generalizable to all participants. Although comparison of baseline characteristics by follow-up participation suggested few sociodemographic and clinical differences, participants who were currently successful might be more likely to participate in the follow-up study. Our follow-up rate likely reflects difficulty in re-engaging participants after the main trial; for most participants eligible for follow-up, more than one year had passed since completing the main treatment trial, with no intervening contact from study staff. Moreover, in some instances, staff members known to treatment-study participants had departed, making it less likely that these early participants would respond to telephone calls from study staff members. Nonetheless, the study provided a unique opportunity to follow this novel population over a longer time.

Another limitation is the switch from in-person interviews during the main trial to telephone interviews during follow-up; we therefore did not collect urine screens. Although previous studies of SUDs comparing data collected by telephone to that obtained via in-person interviews have supported the validity of telephone interviews (Kramer et al., 2009; Midanik and Greenfield, 2003), this may have inflated rates of good outcomes during follow-up. Finally, we did not attempt to distinguish between illicit opioid use and opioid use as prescribed for pain, because no method is generally accepted for making this determination. Although the study inclusion criteria mitigated the likelihood that participants needed an opioid prescription for pain, we cannot rule out some use as prescribed for that indication.

4.2. Conclusions

In the first study examining long-term treatment outcomes of patients with prescription opioid dependence, our results were more encouraging than short-term outcomes from POATS suggested. As reported in our 18-month follow-up study (Potter et al., 2014), and consistent with other literature (Moore et al., 2007; Nielsen et al., 2013; Potter et al., 2013), patients with prescription opioid dependence may have a more promising long-term course, compared with expectations based on long-term follow-up studies of heroin users (Darke et al., 2007; Flynn et al., 2003; Grella and Lovinger, 2011; Hser et al., 2001; Vaillant, 1973). Indeed, a history of occasional heroin use at POATS entry was the only prognostic indicator 42 months later, associated with a higher likelihood of meeting symptomatic criteria for current opioid dependence. Our results are consistent with research on heroin dependence in supporting the value of opioid agonist therapy for prescription opioid dependence; however, half of the follow-up participants reported good outcomes without agonist therapy. One cautionary finding was that some participants initiated heroin use and/or injection use during follow-up. Finally, these data underscore the importance of longer-term follow-up in understanding the course of this increasingly prevalent substance use disorder.

We followed prescription opioid dependent patients post-treatment for 42 months.

Long-term outcomes demonstrated clear improvement from baseline.

32% were abstinent from opioids and not on agonist therapy; 29% were receiving opioid agonist therapy, but met no symptom criteria for current opioid dependence;

Agonist treatment was associated with a greater likelihood of Month-42 abstinence.

8% initiated heroin use and 10% initiated injection heroin use post-treatment.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by grants from NIDA as part of the Cooperative Agreement on the Clinical Trials Network (grants U10 DA015831 and U10 DA020024); and NIDA grants K24 DA022288, K23DA022297, and K23DA035297. NIDA had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; or in the writing of the report. The NIDA Clinical Trials Network Publication Committee reviewed a draft of this manuscript and approved it for submission for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

Drs. Weiss and Potter designed the study and wrote the protocol. Dr. Dreifuss, Mr. Provost, Ms. Dodd, and Ms. McDermott oversaw and participated in the conduct of study assessments. Ms. McDermott and Ms. Srisarajivakul managed the literature searches and summaries of previous related work. Drs. Griffin and Fitzmaurice undertook the statistical analysis. Drs. Weiss and Griffin wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Drs. Potter, McHugh, and Carroll participated in the conceptualization of the paper and reviewed and critically edited ongoing drafts. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Author Disclosures

Dr. Weiss has consulted to Reckitt-Benckiser.

Clinical Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov; registration number NCT00316277; http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00316277.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association (A.P.A.) The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. Fourth edition. A.P.A.; Washington DC.: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brecht ML, Herbeck K. Time to relapse following treatment for methamphetamine use: a long-term perspective on patterns and predictors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;139:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcaterra S, Glanz J, Binswanger IA. National trends in pharmaceutical opioid related overdose deaths compared to other substance related overdose deaths: 1999-2009. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP. The changing face of heroin use in the United States: a retrospective analysis of the past 50 years. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:821–826. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Ross J, Teesson M. The Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS): what have we learnt about treatment for heroin dependence? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26:49–54. doi: 10.1080/09595230601036986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger DS, Marlowe DB, Croft JR, Dugosh KL, Mastro NK, Lee PA, Dematteo DS, Patapis NS. Do research payments precipitate drug use or coerce participation? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;78:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Schottenfeld RS, Gordon L, O'Connor PG. Manual for Standard Medical Management of Opioid Dependence with Buprenorphine. Yale University; New Haven, CT.: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn PM, Joe GW, Broome KM, Simpson DD, Brown BS. Recovery from opioid addiction in DATOS. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2003;25:177–186. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowing L, Ali R, White JM. Buprenorphine for the management of opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. CD002025. 2009 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002025.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Joshi V, Hser YI. Followup of cocaine-dependent men and women with antisocial personality disorder. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2003;25:155–164. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Lovinger K. 30-year trajectories of heroin and other drug use among men and women sampled from methadone treatment in California. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;118:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström K. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br. J. Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Hoffman V, Grella CE, Anglin MD. A 33-year follow-up of narcotics addicts. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2001;58:503–508. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corporation IBM. S.P.S.S. Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. I.B.M. Corp.; Armonk, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM. Heroin use and heroin use risk behaviors among nonmedical users of prescription opioid pain relievers - United States, 2002-2004 and 2008-2010. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JR, Chan G, Kuperman S, Bucholz KK, Edenberg HJ, Schuckit MA, Polgreen LA, Kapp ES, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI, Bierut LJ. A comparison of diagnoses obtained from in-person and telephone interviews, using the semi-structured assessment for the genetics of alcoholism (SSAGA). J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:623–627. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argeriou M. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O'Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284:1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer DE, Woody GE. Individual Drug Counseling. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Rockville, MD.: 1999. NIH Publication No. 99–4380. [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Greenfield TK. Telephone versus in-person interviews for alcohol use: results of the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;72:209–214. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BA, Fiellin DA, Barry DT, Sullivan LE, Chawarski MC, O'Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS. Primary care office-based buprenorphine treatment: comparison of heroin and prescription opioid dependent patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007;22:527–530. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0129-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S, Hillhouse M, Thomas C, Hasson A, Ling W. A comparison of buprenorphine taper outcomes between prescription opioid and heroin users. J. Addict. Med. 2013;7:33–38. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e318277e92e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantalon MV, Fiellin DA, Schottenfeld RS, Gordon L, O'Connor PG. Manual for Enhanced Medical Management of Opioid Dependence with Buprenorphine. Yale University; New Haven, CT.: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Potter JS, Dreifuss JA, Marino EN, Provost S, Dodd DR, Rice LS, Fitzmaurice GM, Griffin ML, Weiss RD. The multi-site prescription opioid addiction treatment study: 18-month outcomes. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.07.009. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter JS, Marino EN, Hillhouse MP, Nielsen S, Wiest K, Canamar CP, Martin JA, Ang A, Baker R, Saxon AJ, Ling W. Buprenorphine/naloxone and methadone maintenance treatment outcomes for opioid analgesic, heroin, and combined users: findings from starting treatment with agonist replacement therapies (START). J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74:605–613. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter JS, Prather K, Kropp F, Byrne M, Sullivan CR, Mohamedi N, Copersino ML, Weiss RD. A method to diagnose opioid dependence resulting from heroin versus prescription opioids using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2010;31:185–188. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH research group Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH three-year drinking outcomes. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1998;22:1300–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD.: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant GE. A 20-year follow-up of New York narcotic addicts. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1973;29:237–241. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1973.04200020065009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Potter JS, Copersino ML, Prather K, Jacobs P, Provost S, Chim D, Selzer J, Ling W. Conducting clinical research with prescription opioid dependence: defining the population. Am. J. Addict. 2010a;19:141–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2009.00017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Potter JS, Fiellin DA, Byrne M, Connery HS, Dickinson W, Gardin J, Griffin ML, Gourevitch MN, Haller DL, Hasson AL, Huang Z, Jacobs P, Kosinski AS, Lindblad R, McCance-Katz EF, Provost SE, Selzer J, Somoza EC, Sonne SC, Ling W. Adjunctive counseling during brief and extended buprenorphine-naloxone treatment for prescription opioid dependence: a 2-phase randomized controlled trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2011;68:1238–1246. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Potter JS, Provost SE, Huang Z, Jacobs P, Hasson A, Lindblad R, Connery HS, Prather K, Ling W. A multi-site, two-phase, Prescription Opioid Addiction Treatment Study (POATS): rationale, design, and methodology. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2010b;31:189–199. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (C.I.D.I.): Core Version 2.1. 1997 [Google Scholar]