Abstract

The influence of psychological symptoms on smoking-lapse behavior is critical to understand. However, this relationship is obscured by comorbidity across multiple forms of psychological symptoms and their overlap with nicotine withdrawal. To address these challenges, we constructed a structural model of latent factors underlying 9 manifest scales of affective and behavioral symptoms and tested relations between latent factors and manifest scale residuals with nicotine withdrawal and smoking lapse in a laboratory analog task. Adult daily smokers (N = 286) completed a baseline session at which several forms of affective and behavioral symptoms were assessed and 2 experimental sessions (i.e., following 16 hr of smoking abstinence and following regular smoking), during which withdrawal symptoms and delay of smoking in exchange for monetary reinforcement, as an analogue for lapse propensity, were measured. A single second-order factor of general psychological maladjustment associated with more severe withdrawal-like symptoms, which in turn associated with shorter delay of smoking. The first-order factors, which tapped qualitatively unique domains of psychological symptoms (low positive affect, negative affect, disinhibition), and the manifest scale residuals provided little predictive power beyond the second-order factor with regard to lapse behavior. Relations among general psychological maladjustment, withdrawal-like symptoms, and lapse were significant in both abstinent and nonabstinent conditions, suggesting that psychological maladjustment, and not nicotine withdrawal per se, accounted for the relation with lapse. These results highlight the potential for smoking-cessation strategies that target general psychological maladjustment processes and have implications for addressing withdrawal-like symptoms among individuals with psychological symptoms.

Keywords: psychological symptoms, nicotine withdrawal, smoking-lapse behavior

Higher levels of psychological symptoms are a risk factor for lapse and early relapse following a quit attempt from smoking (Cook, Spring, McChargue, & Doran, 2010; Leventhal et al., 2012; MacKillop & Kahler, 2009; Mueller et al., 2009; Zvolensky, Stewart, Vujanovic, Gavric, & Steeves, 2009). One hypothesis for the link between psychological symptoms and poor smoking-cessation outcomes is that these symptoms give rise to more severe nicotine withdrawal (Pomerleau, Marks, & Pomerleau, 2000; Weinberger, Desai, & McKee, 2010), which undermines quit attempts due to the motivation to avoid or to suppress these symptoms (Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004; Xian et al., 2005). Although studies provide support for associations among psychological symptoms, nicotine withdrawal, and smoking lapse, two important barriers create difficulties for interpreting these relationships.

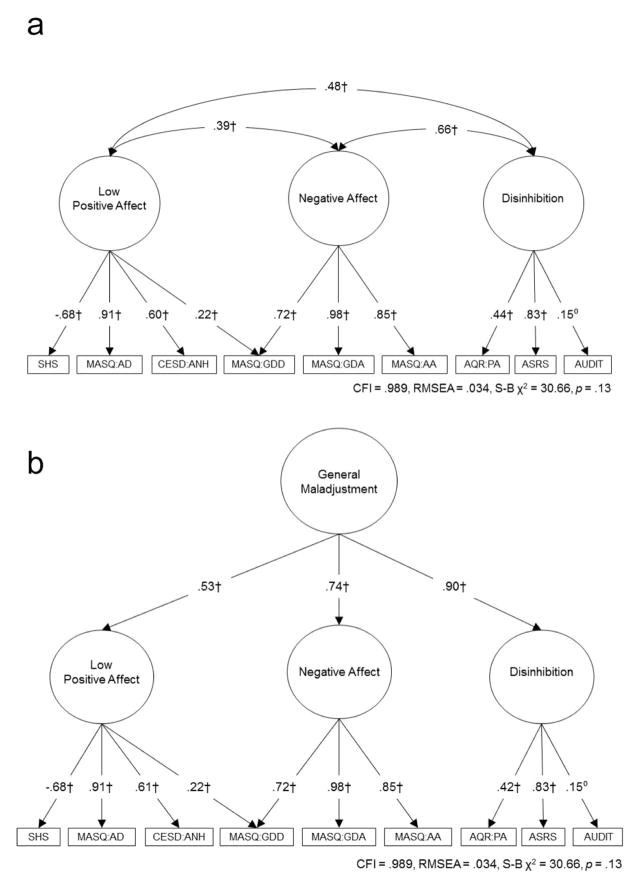

First, extensive comorbidity across different manifest types of psychological symptoms (Clark, Watson, & Reynolds, 1995) obscures the extent to which relations with smoking lapse are due to features specific to or shared across different psychological symptoms. Research suggests that shared, latent liability factors give rise to different manifestations of psychological dysfunction (e.g., anxiety and depression) and likely account for the widespread comorbidity (Brown & Barlow, 2009; Krueger & Markon, 2006). Structural models that can account for shared, latent factors may help to tease apart shared versus specific relations with smoking lapse behavior. Previously, we found that several manifest affective and behavioral symptom scales—low happiness, anhedonia, depression, anxiety, anxious arousal, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms, physical aggression, and alcohol use—loaded onto three latent factors in a sample of adult smokers (N = 338) who completed the baseline session of this study (Ameringer, 2014).1 These scales were selected because they are components of common psychological disorders (i.e., anxiety, mood, disruptive behavior, alcohol use; Babor, Biddle-Higgins, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001; Brown, Chorpita, & Barlow, 1998; Fossati et al., 2007; Gehricke & Shapiro, 2000; Kessler, Adler et al., 2005; Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005) and have received significant attention in the smoking literature (Audrain-McGovern, Rodriguez, Tercyak, Neuner, & Moss, 2006; Kollins, McClernon, & Fuemmeler, 2005; Leventhal, Ramsey, Brown, LaChance, & Kahler, 2008; Nabi et al., 2010). Furthermore, these scales were selected because they are overlapping to a certain extent, both conceptually and empirically, and this empirical and conceptual commonality may collectively tap shared latent constructs that are unidentifiable using the individual manifest indicators. Results from the best-fitting model were consistent with Clark’s (2005) three-factor model of personality and psychopathology, yielding latent factors representative of three biobehavioral temperament systems: positive affectivity, negative affectivity, and disinhibition. These three factors also significantly loaded onto a second-order factor, referred to as general psychological maladjustment, which likely represents broad constructs (e.g., overall severity) and/or common features shared across nearly all types of psychopathology (Weiss, Susser, & Catron, 1998). Figure 1 illustrates these models for the portion of smokers who were included in this study (N = 286, see Method section).

Figure 1.

First-order (a) and second-order (b) latent factor models of psychological symptoms. N = 286. SHS = Subjective Happiness Scale; CESD:ANH = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression-Anhedonia Scale; MASQ = Mood and Anxiety Symptom Scale: AD = Anhedonic Depression Scale, GDD = General Distress Depression Scale, GDA = General Distress Anxious Scale, AA = Anxious Arousal Scale; AQR:PA = Aggression Questionnaire Revised-Physical Aggression Scale; ASRS = Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Error terms and disturbances are not shown. ∘ p < .10. * p < .05. ** p < .01. † p < .001.

The current study uses this model to clarify the extent to which shared versus specific features of the modeled affective and behavioral symptoms predict lapse behavior in a laboratory analog task of smoking lapse, in which delay of smoking is monetarily rewarded (McKee, Krishnan-Sarin, Shi, Mase, & O’Malley, 2006). Associations between the manifest scale residuals (i.e., the portion of unique variance in a scale) and lapse would shed light on specific aspects of psychological symptoms (e.g., somatic symptoms of anxiety separate from general negative affectivity) that may directly influence lapse. Links between the latent factors and lapse would elucidate features shared among psychological symptoms that may directly associate with delay of smoking, irrespective of the specific components of the manifest scales.

A second barrier in this research area is clarifying the source of withdrawal symptoms reported among individuals with psychological symptoms. Symptoms of nicotine withdrawal overlap with psychological symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, and difficulty concentrating (Hughes, Gust, Skoog, Keenan, & Fenwick, 1991). This phenomenological overlap, as well as similar dysregulations in neural transmitter systems (e.g., dopamine; Dunlop & Nemeroff, 2007; McClernon & Kollins, 2008; Watkins, Koob, & Markou, 2000), makes it difficult to disentangle the extent to which withdrawal symptoms reported among individuals with psychological symptoms are a result of sensitivity to tobacco abstinence or an expression of their baseline underlying psychological symptoms. This study attempts to disentangle these two sources by prospectively examining withdrawal in both abstinent and nonabstinent conditions. If abstinence status moderates the relation between psychological symptoms and withdrawal symptoms, which indicates greater abstinence-induced changes as a function of psychological symptoms, such a result might be interpreted as those with higher levels of psychological symptoms exhibit greater signs of nicotine dependence. If, however, a relationship between psychological symptoms and withdrawal symptoms is equivalent between nonabstinent and abstinent conditions (i.e., not moderated by abstinence), perhaps underlying psychological dysfunction is a source of increased withdrawal-like symptoms reported among individuals with psychological symptoms, irrespective of level of tobacco deprivation.

To address these barriers, the main goals of this study were to (a) use a structural model to test shared versus specific relations between psychological symptoms and smoking lapse, (b) test whether withdrawal-like symptoms mediate links between psychological symptoms and smoking lapse, and (c) examine whether abstinence moderates relations between psychological symptoms and withdrawal symptoms. We hypothesized that shared features of psychological symptoms would mainly associate with lapse, based on past research showing stronger relations between shared (vs. specific) features of internalizing syndromes and alcohol dependence (Kushner et al., 2012). Second, we hypothesized that withdrawal symptoms would mediate the link between psychological symptoms and lapse, based on past research demonstrating links between psychological symptoms and withdrawal (Pomerleau et al., 2000; Weinberger et al., 2010) and between withdrawal and early relapse (al’Absi, Hatsukami, Davis, & Wittmers, 2004). Last, we hypothesized that the relation between psychological symptoms and withdrawal would be stronger in the abstinent condition, due to research showing relations between psychological symptoms and withdrawal that are separate from underlying psychological disturbance (McClernon et al., 2011; Strong, Kahler, Ramsey, Abrantes, & Brown, 2004).

Method

This study is a secondary analysis from a study of the influence of psychological symptoms on sensitivity to the effects of tobacco deprivation (Leventhal et al., 2014).

Participants and Procedures

Participants were adult smokers recruited by referrals and community postings (e.g., newspaper, online) advertising a research study on personality and smoking for adult cigarette smokers. Inclusion criteria were (a) ≥ 18 years of age, (b) regular cigarette smoker for ≥2 years, (c) currently smoke ≥10 cigs/day, (d) normal or corrected-to-normal vision with no colorblindness to ensure adequate vision to complete study questionnaires and computer tasks, and (e) fluent in English. Exclusion criteria were (a) active DSM–IV non-nicotine substance dependence, (b) current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSM–IV; APA, 1994) mood disorder or psychotic symptoms (to minimize cognition-impairing effects of acute and severe psychiatric dysfunction) based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I Disorders: Research Version (nonpatient ed.; SCID-I/NP; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002), (c) breath carbon monoxide (CO) levels < 10 ppm at intake to exclude nonregular smokers, (d) use of noncigarette forms of tobacco or nicotine products, (e) plans to quit smoking within 30 days, (f) use of psychiatric medications, or (g) pregnant.

Following a phone screen, participants attended a baseline session involving informed consent, breath CO analysis, psychiatric interview by a trained research assistant, and measures of affective and behavioral symptoms and smoking behaviors. If eligible, participants attended two experimental sessions (abstinent and nonabstinent; order randomized) that started at 12 p.m. All sessions were conducted on separate days and scheduled between 2 and 14 days after the prior session. Participants were instructed to not smoke after 8 p.m. the day before their abstinent session (16 hr of abstinence) and to smoke normally for their nonabstinent session. Based on recommendations that a CO ≥ 10 ppm indicates recent smoking (SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical verification, 2002), participants’ with a CO ≥ 10 ppm at their abstinent session, indicating noncompliance with the abstinent instructions, could return for a second attempt. Those with a CO ≥ 10 ppm on their second attempt were discontinued (n = 6). Procedures were the same across the two sessions except that participants smoked a cigarette of their preferred brand at the start of their nonabstinent session to standardize time from last cigarette. Right after smoking, participants completed several measures, including a measure of nicotine withdrawal. Therefore, withdrawal symptoms were assessed within 15–30 min after smoking. In the abstinent session, following the CO test at the start of the session, participants completed the withdrawal symptom measure. This was the only time the withdrawal assessment was administered in both experimental sessions. About 1 hr after the study began (~30 min after the withdrawal measure in both sessions; 1 hr from smoking in the nonabstinent session), participants completed a smoking lapse task that consisted of a 0–50-min “delay period,” a 1-hr smoking “self-administration period,” and a “rest period” of no smoking that ended 2 hr, 50 min after the start of the delay period. Participants were compensated $204–$212 for completing the study (range due to performance on the smoking task). The study was approved by the University of Southern California’s Institutional Review Board.

Of the 515 participants enrolled in the study, 165 were ineligible at the baseline session due to low baseline CO (n = 103), current psychiatric disorder (n = 39), or other criteria (n = 23). Of the 350 eligible, 58 dropped from the study after entry and 6 twice failed to meet abstinence criteria at their abstinent session, leaving a final sample of 286. Independent t tests revealed no significant differences on any of the affective and behavioral symptom scales, nicotine dependence severity, and cigarettes per day between study completers and noncompleters.

Measures

At the baseline session, participants filled out a personal information questionnaire of demographic information (e.g., age, gender, race). To assess smoking behaviors, participants completed the Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991), a six-item measure of nicotine dependence severity, and a smoking history questionnaire, which asked about smoking history (e.g., age first started smoking, past quit attempts) and smoking patterns (e.g., cigs/day). Participants also completed the following self-report scales to assess affective and behavioral symptoms.

The Subjective Happiness Scale

The SHS (Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999) is a four-item measure of global subjective happiness. Items are rated on a 7-point scale, and a mean score across the items was computed.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Anhedonia Subscale

The CESD:ANH (Radloff, 1977) is a subscale on the 20-item CESD and contains four reverse-scored items relating to feelings of happiness and hopefulness, which were averaged to create a mean score. Participants rate how often they have felt a certain way “during the past week” on a 4-point scale. Confirmatory factor analyses have supported the CESD:ANH subscale (Shafer, 2006) and prior studies have shown that this subscale associates with smoking characteristics (Leventhal et al., 2008; Pomerleau, Zucker, & Stewart, 2003).

The Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire–Short Form

The MASQ-SF (Watson, Clark, et al., 1995; Watson, Weber, et al., 1995) is a 62-item measure of affective symptoms. Participants rate how much they experienced each symptom “during the past week, including today” (1 = not at all to 5 = extremely). The MASQ contains four subscales: (a) Anxious Arousal (MASQ:AA), a measure of somatic tension and hyper-arousal, (b) Anhedonic Depression (MASQ:AD), a measure of loss of interest in life, with reverse-keyed items measuring positive affect, (c) General Distress–Depression (MASQ:GDD), a measure of nonspecific depressed mood experienced in both depression and anxiety, and (d) General Distress–Anxiety (MASQ:GDA), a measure of nonspecific anxious mood experienced in both anxiety and depression. Sum scores were calculated for each of the scales.

The Aggression Questionnaire–Revised

Physical Aggression (AQR:PA; Bryant & Smith, 2001) is a 3-item subscale on the 12-item Aggression Questionnaire–Revised that assesses disposition to physical aggression. Confirmatory factor analysis has supported the empirical uniqueness of this subscale (Bryant & Smith, 2001). Participants rate how characteristic the statements are of them on a 6-point scale. Mean scores across the items were computed.

The Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale

The ASRS (Kessler, Adler, et al., 2005) is a measure of ADHD symptoms in adults and includes nine inattentive items and nine hyperactive-impulsive items. Participants rate each item based on how often they have felt and conducted themselves over the past 6 months (1 = never to 5 = very often). Following prior work (Kessler, Adler, et al., 2005), a total mean score was calculated across the 18 items.

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

The AUDIT (Babor et al., 2001) is a 10-item measure of hazardous alcohol use, alcohol dependence symptoms, and harmful alcohol use. Response options range from 0 to 4, with higher scores reflecting more problematic alcohol use. Participants received a sum score for the scale.

Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale

At the experimental sessions, participants completed a variant of the MNWS (Hughes & Hatsukami, 1986), which served as the mediator variable. The MNWS is a widely used measure of tobacco withdrawal (Hughes, 1992; Hughes et al., 1991). Participants rate a range of withdrawal symptoms they experienced “so far today” on a scale of 0 (never) to 5 (severe). Due to prior research suggesting that craving is distinct from other withdrawal symptoms (Hughes & Hatsukami, 1986), this symptom was eliminated. The remaining withdrawal symptoms were irritable/angry, anxious/tense, difficulty concentrating, restlessness, excessive hunger, physiological symptoms, increased eating, drowsiness, and headaches. Although drowsiness and headaches are not validated withdrawal symptoms (Hughes, 2007), these symptoms have been included in past studies of tobacco withdrawal and have demonstrated significant changes as a function of tobacco deprivation (e.g., Leventhal, Waters, Moolchan, Heishman, & Pickworth, 2010). Furthermore, these symptoms were significantly correlated with the other withdrawal symptoms in both abstinent (rs = 0.25–0.46, ps < .0001) and nonabstinent (rs = 0.22–0.56, ps < .0002) sessions and with the total scale score in both sessions (abstinent: rs = 0.54–0.63, ps < .0001; nonabstinent: rs = 0.55–0.72, ps < .0001). Thus, all 10 symptoms were included to provide a range of possible withdrawal experiences. A mean withdrawal symptom score was computed for both abstinent and nonabstinent sessions.

The outcome variable for this study was “delay of smoking” in a laboratory analogue of lapse behavior (McKee et al., 2006), which measures individual differences in delay of smoking when delaying is monetarily rewarded. In the first part of this task (delay period, which began at ~1:10 p.m.), participants were told they could smoke at any time during the next 50 min but for each 5 min they delayed smoking, they could earn $0.20 up to a maximum of $2.00. The delay period ended when participants decided to smoke or at the end of the 50 min. McKee and colleagues (2012) have demonstrated initial support for the validity of this task as a measure of lapse by showing that longer periods of nicotine deprivation and lower amounts of monetary reinforcement decreased delay of smoking. Furthermore, studies have found that abstinence and individual differences (e.g., delay discounting, nicotine dependence) predicted differences in delay of smoking on this type of task (Dallery & Raiff, 2007; McKee, 2009; McKee et al., 2012). After the delay period, participants began a self-administration period in which they could smoke as much as they wanted over the next hour, though each cigarette cost $0.20. Participants were told that after this hour, they would not be allowed to smoke until the study ended at 4:00 p.m. The main interest of this study was to examine variation in lapse due to psychological symptoms; hence, time delayed (continuous range of 0–50 min) in the delay period (for both abstinent and nonabstinent sessions) was the sole outcome variable.

Data Analysis

Preliminary analysis

To examine psychological severity of the sample, the portion that scored above established cut-off points on relevant scales (MASQ scales, Schulte-van Maaren et al., 2012; ASRS, Kessler, Adler, et al., 2005; AUDIT, Babor et al., 2001) was calculated. Paired t tests were run to test for differences on the experimental session measures between abstinent and nonabstinent sessions. Because certain psychological measures were added throughout the study, participants in the early months of the study were not administered some of the measures. Hence, there is a range of missing data on these measures. Complete ns for the scales were (out of 286): SHS (275), CESD:ANH (286), MASQ (275), AQR:PA (238), ASRS (220), AUDIT (178). Preliminary analyses were conducted in SAS v9.2 (2009).

Primary analysis

All confirmatory factor analytical and structural equation models were conducted in Mplus Version 6 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010), based on the analysis of covariance, and used maximum likelihood (ML) estimation, which is recommended to handle missing data in structural equation modeling (SEM; Allison, 2003). Thus, the full sample of completers (N = 286) was used for main analyses. ML estimation with robust standard errors (MLR) was used to account for potential multivariate non-normality. Model fit evaluation was based on: (a) a nonsignificant Satorra–Bentler-scaled chi-square statistic (S-B χ2; Satorra & Bentler, 1994), which is considered more appropriate when data are not normally distributed (Chou, Bentler, & Satorra, 1991), (b) a comparative fit index (CFI) > .95, and (c) a root mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) < .06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). All variables were standardized prior to inclusion in the models. Before primary analyses, confirmatory factor analysis was used to test whether the 3-factor model of psychological symptoms identified in the sample of smokers that completed the baseline session (N = 338) maintained acceptable fit in the portion that completed all sessions (N = 286).

Shared and specific relations between psychological symptoms and delay

To examine shared relations between psychological symptoms and delay, regression paths from each of the first-order factors to delay were added to the model. These paths were first added separately to examine their independent relations and then all paths were added simultaneously to examine their unique relations (i.e., the relation between each factor and delay after adjusting for the shared variance among the factors). If the factors independently associated with delay but not uniquely (i.e., associations between the factors and delay dropped below significance when paths from all factors were in the model), the relation between the second-order factor and delay was tested. Next, paths from the residuals (i.e., the unexplained variance) of each manifest scale to delay were successively included in the model to examine specific relations between psychological symptoms and delay, after controlling for the influence of the latent factors. We obtained the residuals for each scale and regressed delay on the residuals following a series of steps for Mplus (Muthén & Muthén “Regressing on a Residual”), similar to prior work (Kushner et al., 2012; South, Krueger, & Iacono, 2011). Only paths that were significant between the latent factors and the residuals with smoking delay were kept for the mediation model.

Withdrawal mediation model

After identifying all shared and specific relations between psychological symptoms and delay, mean withdrawal-symptom scores were added to the model to test whether they mediated any identified relations. The MODEL INDIRECT command was used to obtain the indirect (based on the delta method; MacKinnon, 2008) and total effects.

Moderation by abstinence condition analyses

For all models previously described, we used raw scores for withdrawal and delay as repeated measures, which participants completed at both abstinent and nonabstinent sessions, and included both abstinent and nonabstinent measures in the same model. Then, to test whether abstinence-provoked changes in withdrawal and delay differed as a function of psychological symptoms, we examined whether abstinent condition significantly moderated the relation of psychological symptoms to withdrawal and to delay. To do this, the paths representing the same relation across abstinent and nonabstinent conditions were constrained to be equal. The same model was then rerun after releasing the constraints and model fit improvement was assessed with the Satorra–Bentler-scaled chi-square difference test (Satorra & Bentler, 2001). If model fit significantly improved, suggesting a significant difference in the paths and moderation by abstinence status, these paths were left freed in the model and interpreted as such. If model fit did not improve, implying no moderation by abstinence, these paths were constrained in the model and consequently interpreted. This moderation test is statistically equivalent to using a change score (abstinent–nonabstinent) in that this tests whether individuals with psychological symptoms experience a greater increase in withdrawal-like symptoms, or shorter delay in smoking lapse, when abstinent. We chose to use raw scores and to examine moderation by abstinence, rather than solely using abstinence-induced changes scores, because this allowed us to test the main effects of psychological symptoms on withdrawal, in addition to interaction effects. Also, this method allowed for the ability to disentangle whether withdrawal-like symptoms reported among individuals with psychological symptoms were resulting from nicotine removal or underlying psychological dysfunction.

Covariates

Demographics (age, gender, race) and smoking variables (FTND, cigs/day) were regressed on withdrawal symptoms and delay and allowed to covary with the latent factors. In separate regression models, both the FTND and cigs/day associated with more severe withdrawal-like symptoms in abstinent and nonabstinent conditions, respectively (FTND: β = .27, p < .001, β = .15, p < .05; cigs/day: β = .19, p < .01, β = .15, p < .05), and the FTND associated with shorter delay of smoking in the abstinent condition (β = −.16, p < .01). However, including these variables in the structural model yielded no substantive changes to the primary results; therefore, these variables were not included in the final models. Primary results are reported as standardized beta weights (βs) and significance was set at p < .05. All tests were two-tailed except for the Satorra–Bentler chi-square difference tests, which assessed model-fit improvement.

Results

Preliminary Results

On average, participants were 44.0 (SD = 10.6) years of age, 68% male, and were: 52% African American, 34% White, and 14% other, with 15% Hispanic. Participants started smoking around age 19.5 (SD = 5.6), smoked approximately 16.7 (SD = 7.0) cigs/day, had an average FTND level of 5.3 (SD = 1.9), indicating moderate nicotine dependence severity, and reported 4.0 (SD = 7.7) previous quit attempts. CO levels were significantly different between nonabstinent (M = 27.98, SD = 12.84) and abstinent (M = 5.55, SD = 2.14) sessions (t = −30.14, p < .001). Abstinence also had a main effect on increasing withdrawal-like symptoms (t = 10.99, p < .001) and reducing delay time (t = −11.32, p < .001; see Table 1 for mean scores).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations of Psychological Symptom Scales, Withdrawal Symptoms, and Length of Delay

| Scale | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SHS | 5.27 (1.13) | (.79) | ||||||||||||

| 2. CESD:ANH | 0.72 (0.66) | −.42*** | (.70) | |||||||||||

| 3. MASQ:AD | 52.94 (14.03) | −.62*** | .55*** | (.90) | ||||||||||

| 4. MASQ:GDD | 17.68 (7.11) | −.35*** | .28*** | .46*** | (.92) | |||||||||

| 5. MASQ:GDA | 15.17 (5.51) | −.28*** | .20*** | .35*** | .80*** | (.87) | ||||||||

| 6. MASQ:AA | 21.68 (6.95) | −.27*** | .19** | .30*** | .68*** | .83*** | (.90) | |||||||

| 7. AQR:PA | 1.80 (1.04) | −.20** | .15* | .13 | .26*** | .30*** | .37*** | (.79) | ||||||

| 8. ASRS | 2.18 (0.64) | −.29*** | .27*** | .38*** | .46*** | .54*** | .51*** | .36*** | (.92) | |||||

| 9. AUDIT | 3.47 (4.98) | −.05 | .13 | −.04 | .03 | −.01 | .04 | .19* | .16* | (.89) | ||||

| 10. MNWS:A | 1.64 (1.15) | −.11 | .10 | .18** | .20*** | .29*** | .27*** | .19** | .32*** | −.02 | (.89) | |||

| 11. MNWS:NA | 0.94 (0.98) | −.16** | .21*** | .28*** | .37*** | .45*** | .40*** | .25*** | .45*** | .13 | .49*** | (.90) | ||

| 12. DELAY:A | 23.93 (22.92) | .05 | −.05 | −.07 | .05 | −.04 | −.01 | −.10 | −.08 | .10 | −.23*** | −.17** | — | |

| 13. DELAY:NA | 39.50 (17.63) | .09 | −.07 | −.10 | −.13* | −.13* | −.07 | −.04 | −.14* | −.08 | −.10 | −.20** | .36*** | — |

Note. N = 286. Cronbach’s alphas are on the diagonal. SHS = Subjective Happiness Scale; CESD:ANH = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression–Anhedonia Scale; MASQ = Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire; AD = Anhedonic Depression Scale; GDD = General Distress Depression Scale; GDA = General Distress Anxious Scale; AA = Anxious Arousal Scale; AQR:PA = Aggression Questionnaire Revised–Physical Aggression Scale; ASRS = Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; MNWS = Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale; delay = length of delay to first cigarette (0–50 min): A = abstinent; NA = nonabstinent.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and correlations of variables in the models. The scales that loaded onto a specific first-order latent factor (see Figure 1) exhibited significant but not markedly high correlations, indicating that these scales were not entirely overlapping constructs and still contained unique components. Scores on most of the psychological scales reflected low severity and high between-participant variability. Percents of those who scored above established clinically relevant cut-off points on scales were: MASQ:AD = 55.3%, MASQ:GDD = 18.6%, MASQ:GDA = 12.7%, MASQ:AA = 9.1%, ASRS = 6.4%, and AUDIT = 10.1%.

Primary Results

The first and second-order models of affective and behavioral symptoms had acceptable fit (see Figure 1).2 Except for the loading of the AUDIT on the disinhibition factor, which was a non-significant trend (p < .10), all other indicators significantly loaded onto their respective factors and the first-order factors significantly loaded onto the second-order factor. The superior fit of the three-factor model, in which positive affect, negative affect, and disinhibition were distinguished from one another (vs. collapsed into a single factor), and the moderate-sized correlations among the first-order factors, indicated that these first-order factors were empirically distinct from one another.

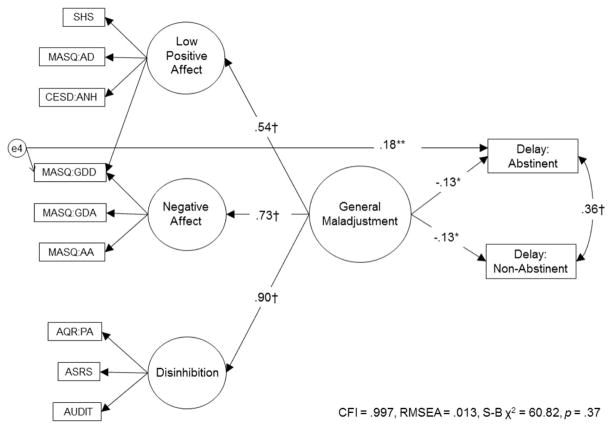

Shared and specific relations between psychopathological symptoms and delay

When entered in the model independently, low positive affect and disinhibition each significantly associated with shorter delay (ps < .05). Negative affect associated with shorter delay at a nonsignificant trend (p < .10). However, when paths from all factors were added to the model, all relations reduced below significance (ps > .10), indicating that each factor did not uniquely associate with delay. Thus, we tested the relation between the second-order factor and delay and found a significant inverse relationship, such that more severe general maladjustment associated with shorter delay. Model fit did not improve when paths from general maladjustment to delay–abstinent and to delay–nonabstinent were freed, indicating no moderation by abstinence. When each of the indicator residuals were added to the model, only the MASQ:GDD predicted delay beyond the second-order factor. Model fit significantly improved when paths from MASQ:GDD to delay–abstinent and to delay–nonabstinent were freed. Upon freeing these paths, the MASQ: GDD residual associated with longer delay–abstinent (β = .17, p < .05), but did not associate with delay–nonabstinent (β = −.03, p > .05). The final model of significant paths to delay had acceptable fit (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Final model of significant paths from latent factors and residuals to length of delay to first cigarette (0–50 minutes). SHS = Subjective Happiness Scale; CESD:ANH = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression-Anhedonia Scale; MASQ = Mood and Anxiety Symptom Scale: AD = Anhedonic Depression Scale, GDD = General Distress Depression Scale, GDA = General Distress Anxious Scale, AA = Anxious Arousal Scale; AQR:PA = Aggression Questionnaire Revised-Physical Aggression Scale; ASRS = Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Only the residuals significantly associated with delay are shown in the model. All results are standardized. Error terms, disturbances, and indicator factor loadings are not shown. * p < .05. ** p < .01. † p < .001.

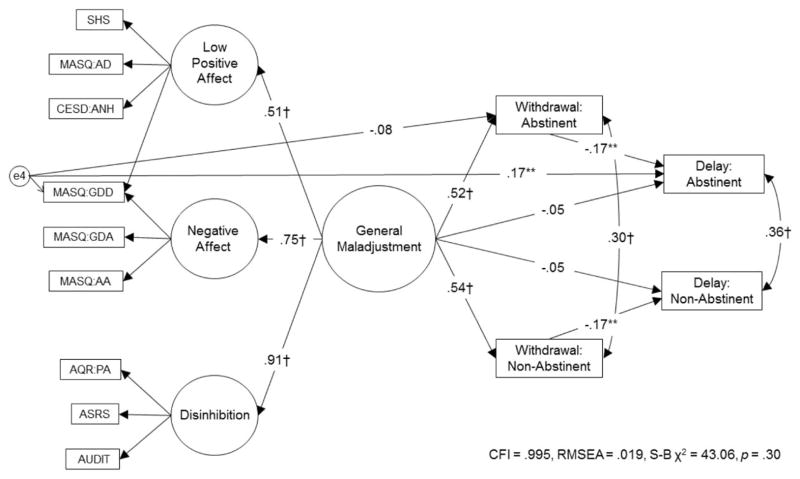

Withdrawal symptoms

In the mediation model, general maladjustment significantly associated with more severe withdrawal-like symptoms in both abstinent and nonabstinent conditions. In turn, more severe withdrawal-like symptoms inversely associated with delay in both conditions. Withdrawal-like symptom severity significantly mediated the association between more severe general maladjustment and shorter delay. The indirect effect of this path was significant (see Table 2), and the direct association between general maladjustment and delay dropped below significance. Abstinence status did not moderate any of these relations (psychopathological symptoms to withdrawal-like symptoms and withdrawal to delay), thus these paths were kept constrained. The MASQ:GDD residual did not associate with abstinent withdrawal-like symptoms. The final mediation model had acceptable fit (see Figure 3).3

Table 2.

Direct, Indirect, and Total Effects From the Withdrawal Mediation Model

| Predictors | Outcomes

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNWS: Abstinent β | MNWS: Nonabstinent β | Delay: Abstinent β | Delay: Nonabstinent β | |

| General maladjustment | ||||

| Direct effects | .52*** | .54*** | −.05 | −.05 |

| Indirect effects | — | — | −.09** | −.09** |

| Total effects | .52*** | .54*** | −.14* | −.14* |

| MASQ:GDD residual | ||||

| Direct effects | −.08 | — | .17** | — |

| Indirect effects | — | — | .01 | — |

| Total effects | −.08 | — | .19** | — |

| MNWS: Abstinent | .30*** | — | −.17** | — |

| MNWS: Nonabstinent | — | .30*** | — | −.17** |

| R2 | .27*** | .30*** | .08** | .04* |

Note. N = 286. MNWS = Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale; delay = length of delay to first cigarette (0–50 min); general maladjustment = single second-order latent factor of psychopathology; MASQ:GDD = Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire: General Distress Depression Scale; residual = portion of the MASQ:GDD that is independent from the latent factors. R2 = amount of variance explained in the index variable by all of the variables in the final mediation model. β = β weights (standardized regression coefficients). Significant findings are in bold. Paths that were not applicable or were omitted by the final model are not reported.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 3.

Model of withdrawal-like symptom severity mediating links between psychological symptoms and length of delay to first cigarette (0–50 minutes). SHS = Subjective Happiness Scale; CESD:ANH = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression-Anhedonia Scale; MASQ = Mood and Anxiety Symptom Scale: AD = Anhedonic Depression Scale, GDA = General Distress Anxious Scale, GDD = General Distress Depression Scale, AA = Anxious Arousal Scale; AQR:PA = Aggression Questionnaire Revised-Physical Aggression Scale; ASRS = Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Only the residuals significantly associated with delay are shown in the model. All results are standardized. Error terms, disturbances, and indicator factor loadings are not shown. * p < .05. ** p < .01. † p < .001.

Discussion

This study found that a higher-order factor tapping general psychological maladjustment was most meaningful for explaining the relation between various manifestations of affective and behavioral symptoms and shorter delay of smoking in a laboratory analog task of smoking lapse. Even though the structural model suggested three qualitatively distinct lower-order factors of psychological symptoms (low positive affect, negative affect, disinhibition), each of these individual factors were not associated with delay after controlling for their covariance. Yet, the higher-order factor composed of the three lower-order factors significantly associated with shorter smoking delay. Furthermore, the residuals of the manifest scales generally were not associated with delay beyond the second-order factor. Therefore, we conclude that an overall, shared construct across all manifest indicators, such as variance in psychological severity, is a parsimonious explanatory factor of psychological symptoms in variance of lapse behavior.

The general maladjustment factor associated with more severe withdrawal-like symptoms and shorter delay of smoking, irrespective of abstinence condition. In other words, general maladjustment was not associated with the degree of abstinence-induced changes in withdrawal-like symptoms or delay of smoking. These results suggest that individuals with psychological symptoms may more consistently report withdrawal-like symptoms (e.g., anxiety) at greater levels, regardless of abstinence, because of the expression of their underlying psychological disturbance (Gray, Baker, Carpenter, Lewis, & Upadhyaya, 2010). In addition, these findings indicate that general maladjustment may motivate smoking lapse across differing abstinence levels. However, because ~15–30 min elapsed between smoking and the withdrawal symptom assessment and about 1 hr elapsed between smoking and the start of the delay period in the nonabstinent session, it is possible that individuals with psychological symptoms were in a withdrawn state at the start of, and increasingly throughout, these assessments. Hence, this finding may alternately reflect an acute sensitivity to nicotine removal and early withdrawal-like symptom manifestation among individuals with psychological symptoms (Hendricks, Ditre, Drobes, & Brandon, 2006). Therefore, research investigating variation in withdrawal symptoms and smoking lapse across different lengths of abstinence (e.g., immediately following a cigarette, after extended periods of abstinence) is needed to examine the generalizability of these findings.

Unexpectedly, the MASQ:GDD residual associated with longer abstinent smoking delay. The items on the MASQ:GDD reflected mainly pessimistic cognitions and low self-esteem. Therefore, it may be that separating a general tendency toward negative affect and psychological maladjustment (captured by the latent factors) from a pessimistic cognitive construct (captured by the residual of the manifest MASQ:GDD scale) removes a suppressor effect in which this pessimistic cognitive style protects against smoking lapse in this task.

Mediational analyses showed that individuals with greater general maladjustment reported more severe withdrawal-like symptoms immediately before the smoking-lapse task, which in turn predicted faster smoking regardless of the abstinence condition. Thus, individuals with affective and behavioral symptoms may be at increased risk for smoking lapse behavior to manage acute affective or behavioral symptoms that are picked up by withdrawal measures and experienced across various abstinence states (Baker et al., 2004; Xian et al., 2005). Therefore, it may be important for clinicians to take into account that individuals with psychological symptoms may report symptoms picked up by withdrawal scales, such as the MNWS, even when minimally abstinent, which may in turn influence smoking-lapse behavior.

These results must be interpreted with respect to several limitations. The affective and behavioral symptom scales were chosen because they are components of common mental disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety, disruptive behavior, alcohol use) that have shown relations with smoking (Lasser et al., 2000). However, many different types and levels of psychological symptoms could have been included that may have changed the model structure and subsequent results. Furthermore, individuals who were currently on psychiatric medications or who met criteria for current mood disorder or substance dependence were excluded, which could have influenced the magnitude and pattern of relations. Therefore, conclusions are limited to relatively low to moderate levels of psychological symptoms. Nonetheless, prior research documents that subclinical variation in depressive symptoms predicts lapse risk (Leventhal et al., 2008); hence, the current results may generalize to a restricted, albeit clinically important, range of the continuum of psychological functioning. Given the laboratory analogue design using smokers not interested in quitting, it is unclear how these results would extend to naturalistic quit attempts. Also, there was a high rate of missing data on some of the psychological measures. Although maximum likelihood estimation was used to handle missing data for primary analyses, more complete data would be optimal. Last, we opted to maintain a p < .05 significance level to provide a broad picture of interrelations using a structural model; as such, these findings are subject to Type I error due to the multiple tests run.

Despite these limitations, this study provides novel structural evidence for the importance of considering underlying, shared constructs in relations across different manifest psychological symptoms, withdrawal, and smoking lapse. This study also benefitted from using prospective withdrawal measures across experimentally manipulated abstinent and nonabstinent conditions. Our results indicate that psychological symptoms may be an important source of withdrawal-like symptoms, even at minimal abstinence levels, and should be considered in smoking-cessation treatments. Furthermore, this finding may suggest that individuals with higher levels of psychological symptoms require cessation treatment beyond traditional nicotine-replacement therapy, which aims to alleviate withdrawal symptoms resulting from nicotine removal. For example, interventions that combine nicotine-replacement therapy with strategies that help manage reactions to and increase tolerance of withdrawal-like experiences (e.g., Brown et al., 2008) may prove beneficial for smokers with various forms of psychological symptoms. Broadly, this study has illustrated the complexity of the interrelations among psychological symptoms, withdrawal, and smoking lapse, and has highlighted the importance of nuanced assessment and methodological strategies to isolate the etiological and clinical relevance of such paths.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01-DA026831. During preparation of the manuscript, Katherine Ameringer was supported as a predoctoral fellow on a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award from the NIH, National Cancer Institute (Grant T32-CA009492).

Footnotes

This previous study used confirmatory factor analysis to test three competing models of psychological symptoms: a one-factor (general maladjustment), a two-factor (internalizing–externalizing), and a three-factor (low positive affect–negative affect–disinhibition) model in two samples, college-student and adult smokers (the baseline sample for the current study). The psychological symptom scales were chosen because they provided adequate representation of constructs that could map onto any one of the three tested models. The purpose of this past study was to identify the best-fitting model of psychological symptoms that have been linked to smoking and to examine the generalizability of the model across diverse samples.

Because the second-order model was an alternate way of expressing the significant correlations among the first-order factors, model fit for these two models was identical.

Two alternate versions of the final mediation model were run to help with interpretation of results. In the first model, the single item of craving from the MNWS was used instead of the composite withdrawal score. In this model, craving significantly associated with shorter delay (abstinent and nonabstinent); however, general maladjustment did not associate with either abstinent or nonabstinent craving. In the second model, withdrawal and delay change scores (abstinent minus nonabstinent) were calculated and included in the model as an alternative to examining moderation by abstinence status. In this model, general maladjustment did not associate with change in either withdrawal or delay, and no mediation effects were present.

References

- al’Absi M, Hatsukami D, Davis GL, Wittmers LE. Prospective examination of effects of smoking abstinence on cortisol and withdrawal symptoms as predictors of early smoking relapse. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;73:267–278. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data techniques for structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:545–557. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ameringer KJ. Doctoral dissertation. 2014. Using a structural model of psychopathology to distinguish relations between shared and specific features of psychopathology, smoking, and underlying mechanisms. Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3609818) [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Tercyak KP, Neuner G, Moss HB. The impact of self-control indices on peer smoking and adolescent smoking progression. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31:139–151. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Biddle-Higgins JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in primary health care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2002;4:149–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Palm KM, Strong DR, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, Gifford EV. Distress tolerance treatment for early-lapse smokers: Rationale, program description, and preliminary findings. Behavior Modification. 2008;32:302–332. doi: 10.1177/0145445507309024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Barlow DH. A proposal for a dimensional classification system based on the shared features of the DSM–IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for assessment and treatment. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:256–271. doi: 10.1037/a0016608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM–IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:179–192. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.107.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant FB, Smith BD. Refining the architecture of aggression: A measurement model for the Buss-Perry aggression questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality. 2001;35:138–167. doi: 10.1006/jrpe.2000.2302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chou CP, Bentler PM, Satorra A. Scaled test statistics and robust standard errors for non-normal data in covariance structure analysis: A Monte Carlo study. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 1991;44:347–357. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1991.tb00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA. Temperament as a unifying basis for personality and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:505–521. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D, Reynolds S. Diagnosis and classification of psychopathology: Challenges to the current system and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology. 1995;46:121–153. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.46.020195.001005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J, Spring B, McChargue D, Doran N. Effects of anhedonia on days to relapse among smokers with a history of depression: A brief report. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12:978–982. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Raiff BR. Delay discounting predicts cigarette smoking in a laboratory model of abstinence reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 2007;190:485–496. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0627-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop BW, Nemeroff CB. The role of dopamine in the pathophysiology of depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:327–337. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured clinical interview for DSM–IV–TR Axis I disorders: Research version (nonpatient ed.; SCID-I/NP) New York, NY: Biometrics Research, Columbia University; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fossati A, Barratt ES, Borroni S, Villa D, Grazioli F, Maffei C. Impulsivity, aggressiveness, and DSM–IV personality disorders. Psychiatry Research. 2007;149:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehricke J, Shapiro D. Reduced facial expression and social context in major depression: Discrepancies between facial muscle activity and self-reported emotion. Psychiatry Research. 2000;95:157–167. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(00)00168-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray KM, Baker NL, Carpenter KC, Lewis AL, Upadhyaya HP. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Confounds Nicotine Withdrawal Self-Report in Adolescent Smokers. The American Journal on Addictions. 2010;19:325–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks PS, Ditre JW, Drobes DJ, Brandon TH. The early time course of smoking withdrawal effects. Psychopharmacology. 2006;187:385–396. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0429-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Tobacco withdrawal in self-quitters. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:689–697. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.60.5.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Effects of abstinence from tobacco: Valid symptoms and time course. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9:315–327. doi: 10.1080/14622200701188919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Gust SW, Skoog K, Keenan RM, Fenwick JW. Symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. A replication and extension. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:52–59. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810250054007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Hatsukami D. Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43:289–294. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030107013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, Demler O, Faraone S, Hiripi E, Walters EE. The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:245–256. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704002892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM–IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.7.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollins SH, McClernon FJ, Fuemmeler BF. Association between smoking and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in a population-based sample of young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:1142–1147. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE. Reinterpreting comorbidity: A model-based approach to understanding and classifying psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2006;2:111–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Wall MM, Krueger RF, Sher KJ, Maurer E, Thuras P, Lee S. Alcohol dependence is related to overall internalizing psychopathology load rather than to particular internalizing disorders: Evidence from a national sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36:325–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01604.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Japuntich SJ, Piper ME, Jorenby DE, Schlam TR, Baker TB. Isolating the role of psychological dysfunction in smoking cessation: Relations of personality and psychopathology to attaining cessation milestones. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:838–849. doi: 10.1037/a0028449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Ramsey SE, Brown RA, LaChance HR, Kahler CW. Dimensions of depressive symptoms and smoking cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:507–517. doi: 10.1080/14622200801901971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Trujillo M, Ameringer K, Tidey JW, Sussman S, Kahler CW. Anhedonia and the relative reward value of drug and non-drug reinforcers in cigarette smokers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014;123:375–386. doi: 10.1037/a0036384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Waters AJ, Moolchan ET, Heishman SJ, Pickworth WB. A qunatitative analysis of subjective, cognitive, and physiological manifestations of the acute tobacco abstinent syndrome. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:1120–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Lepper HS. A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research. 1999;46:137–155. doi: 10.1023/A:1006824100041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Kahler CW. Delayed reward discounting predicts treatment response for heavy drinkers receiving smoking cessation treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;104:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York, NY: Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McClernon FJ, Kollins SH. ADHD and smoking: From genes to brain to behavior. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1141:131–147. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClernon FJ, Van Voorhees EE, English J, Hallyburton M, Holdaway A, Kollins SH. Smoking withdrawal symptoms are more severe among smokers with ADHD and independent of ADHD symptom change: Results from a 12-day contingency-managed abstinence trial. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2011;13:784–792. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA. Developing human laboratory models of smoking lapse behavior for medication screening. Addiction Biology. 2009;14:99–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Krishnan-Sarin S, Shi J, Mase T, O’Malley SS. Modeling the effect of alcohol on smoking lapse behavior. Psychopharmacology. 2006;189:201–210. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0551-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Weinberger AH, Shi J, Tetrault J, Coppola S. Developing and validating a human laboratory model to screen medications for smoking cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;14:1362–1371. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller ET, Landes RD, Kowal BP, Yi R, Stitzer ML, Burnett CA, Bickel WK. Delay of smoking gratification as a laboratory model of relapse: Effects of incentives for not smoking, and relationship with measures of executive function. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2009;20:461–473. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283305ec7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Authors; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Regressing on a residual. n.d [PDF file]. Retrieved from http://www.statmodel.com/faq.shtml.

- Nabi H, Hall M, Koskenvuo M, Singh-Manoux A, Oksanen T, Suominen S, Vahtera J. Psychological and somatic symptoms of anxiety and risk of coronary heart disease: The health and social support prospective cohort study. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau CS, Marks JL, Pomerleau OF. Who gets what symptom? Effects of psychiatric cofactors and nicotine dependence on patterns of smoking withdrawal symptomatology. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2000;2:275–280. doi: 10.1080/14622200050147547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau CS, Zucker AN, Stewart AJ. Patterns of depressive symptomatology in women smokers, ex-smokers, and never-smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:575–582. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00257-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. The SAS System for Windows (Version 9.2) Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. Corrects to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66:507–514. doi: 10.1007/BF02296192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte-van Maaren YWM, Carlier IVE, Zitman FG, van Hemert AM, de Waal MWM, van Noorden MS, Giltay EJ. Reference values for generic instruments used in routine outcome monitoring: The Leiden routine outcome monitoring study. BioMed Central Psychiatry. 2012;12 doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer AB. Meta-analysis of the factor structures of four depression questionnaires: Beck, CES-D, Hamilton, and Zung. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62:123–146. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South SC, Krueger RF, Iacono WG. Understanding general and specific connections between psychopathology and marital distress: A model based approach. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:935–947. doi: 10.1037/a0025417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong DR, Kahler CW, Ramsey SE, Abrantes A, Brown RA. Nicotine withdrawal among adolescents with acute psychopathology: An item response analysis. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:547–557. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001696484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins SS, Koob GF, Markou A. Neural mechanisms underlying nicotine addiction: Acute positive reinforcement and withdrawal. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2000;2:19–37. doi: 10.1080/14622200050011277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Weber K, Assenheimer JS, Strauss ME, McCormick RA. Testing a tripartite model: II. Exploring the symptom structure of anxiety and depression in student, adult, and patient samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:15–25. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.104.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Weber K, Assenheimer JS, Clark LA, Strauss ME, McCormick RA. Testing a tripartite model: I. Evaluating the convergent and discriminant validity of anxiety and depression symptom scales. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:3–14. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.104.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Desai RA, McKee SA. Nicotine withdrawal in U.S. smokers with current mood, anxiety, alcohol use, and substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;108:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B, Susser K, Catron T. Common and specific features of childhood psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:118–127. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.107.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xian H, Scherrer JF, Madden PA, Lyons MJ, Tsuang M, True WR, Eisen SA. Latent class typology of nicotine withdrawal: Genetic contributions and association with failed smoking cessation and psychiatric disorders. Psychological Medicine, April. 2005;2005:409–419. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704003289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Stewart SH, Vujanovic AA, Gavric D, Steeves D. Anxiety sensitivity and anxiety and depressive symptoms in the prediction of early smoking lapse and relapse during smoking cessation treatment. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11:323–331. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]