Abstract

Background

With improved survival rates, short- and long-term respiratory complications of premature birth are increasing, adding significantly to financial and health burdens in the United States. In response, in May 2010, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) funded a 5-year $18.5 million research initiative to ultimately improve strategies for managing the respiratory complications of preterm and low birth weight infants. Using a collaborative, multi-disciplinary structure, the resulting Prematurity and Respiratory Outcomes Program (PROP) seeks to understand factors that correlate with future risk for respiratory morbidity.

Methods/Design

The PROP is an observational prospective cohort study performed by a consortium of six clinical centers (incorporating tertiary neonatal intensive care units [NICU] at 13 sites) and a data-coordinating center working in collaboration with the NHLBI. Each clinical center contributes subjects to the study, enrolling infants with gestational ages 23 0/7 to 28 6/7 weeks with an anticipated target of 750 survivors at 36 weeks post-menstrual age. In addition, each center brings specific areas of scientific focus to the Program. The primary study hypothesis is that in survivors of extreme prematurity specific biologic, physiologic and clinical data predicts respiratory morbidity between discharge and 1 year corrected age. Analytic statistical methodology includes model-based and non-model-based analyses, descriptive analyses and generalized linear mixed models.

Discussion

PROP incorporates aspects of NICU care to develop objective biomarkers and outcome measures of respiratory morbidity in the <29 week gestation population beyond just the NICU hospitalization, thereby leading to novel understanding of the nature and natural history of neonatal lung disease and of potential mechanistic and therapeutic targets in at-risk subjects.

Trial registration

Clinical Trials.gov NCT01435187.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12887-015-0346-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Prematurity, Infant, Preterm, Chronic lung disease, Bronchopulmonary dysplasia

Background

Approximately 1 out of every 9 live births in the United States occurs prematurely. Preterm birth is associated with serious respiratory illnesses that are especially problematic in the first two years of life. Better understanding of the etiologies and risk factors for respiratory disease of prematurity is essential to effectively prevent and treat these disorders. The risks of developing respiratory disease in preterm infants are inversely related to their gestational age at birth (GA), with a diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia further increasing this risk. Yet, at any given GA, reliable clinical markers to quantify severity of future disease or predict which infants will develop long-term respiratory complications are lacking. Objective biochemical or physiologic measures for either clinical or research purposes are also rare. In recognition of the gaps in definitional, operational and mechanistic understanding, the Prematurity and Respiratory Outcomes Program (PROP) was created to characterize and develop a means of predicting clinically meaningful and persistent pulmonary disease of prematurity, in the context of current neonatal intensive care practices [1]. It is a multi-disciplinary, six-center, 13-site organization (Table 1) fostering the collaboration of neonatologists, pulmonologists, and basic scientists working to identify biomarkers of one-year respiratory morbidity and mortality in a cohort of more than 750 extremely preterm infants. The data gathered through this project will also be used to investigate mechanisms contributing to respiratory disease of the preterm newborns and to provide high-resolution phenotyping of disease severity for use in clinical applications and future trials.

Table 1.

Single center programs and specific projects

| Program center | # Clinical sites | Project objectives | # Enrolled |

|---|---|---|---|

| University of Pennsylvania | 0 | Data Coordinating Center for the PROP | N/A |

| Duke University/Indiana University | 2 | Gastrin-releasing peptide and bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 105 |

| University of Rochester/University at Buffalo | 2 | Functional and lymphocytic markers of respiratory morbidity in hyperoxic preterm infants | 142 |

| Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center | 3 | Biomarkers of immunologic function and preterm respiratory outcomes | 111 |

| University of California, San Francisco | 3 | Influence of the nitric oxide pathway and inflammation on preterm respiratory outcomes | 161 |

| Vanderbilt University | 2 | Immaturity and genetic variation in urea cycle-nitric oxide and glutathione pathways modulation of BPD phenotype | 184 |

| Washington University | 1 | Influence of the enteric microbiome on the genesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 132 |

This report of the study protocol details the design of the PROP study and illustrates the breadth of data and biospecimens that will be available at the end of the one-year follow-up period. It also suggests a multiplicity of future studies investigating complications and therapeutic interventions for the respiratory complications of prematurity.

Methods/Design

The PROP required each Center to submit a single-site biomarker proposal along with a potential multi-site shared protocol for measuring respiratory phenotypes and outcomes of extremely preterm infants. The center-specific studies are reflected in the project objectives in Table 1, while the multicenter protocol was a collaborative effort.

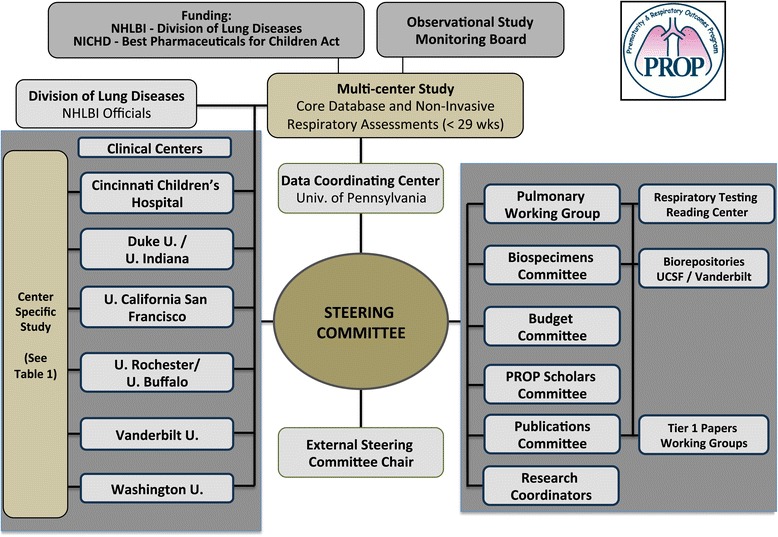

The PROP structure is depicted in Figure 1. In October 2011, an additional center composed of 2 clinical sites (Indiana University and Duke University) was added to the program based on the alignment of their research objectives. Each clinical center and the Data Coordinating Center (DCC) are represented on the Steering Committee, with each center contributing to the data collection, coordination and oversight of the multicenter components. The DCC manages clinical report forms, provides support for standardization of definitions, data collection, quality monitoring and analysis. Oversight is provided by an NHLBI appointed steering committee chair, NIH officials, and an observational and safety monitoring board (OSMB) with representatives from neonatology, pediatric pulmonology and biostatistics. The steering committee holds a conference call every 2 weeks, meets in-person twice yearly and in addition, holds working meetings at the American Thoracic Society and Pediatric Academic Society conferences. The committee identifies and resolves issues, encourages the centers to present updates of their projects, and determines future directions for the consortium. Working groups developed the initial protocols for biospecimen acquisition (Additional file 1), maternal and neonatal database elements (Additional files 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6) and respiratory measurements (Additional files 7 and 8: Table S1); these committees also provided regular monitoring of the standardization and quality of the measurements. The publications committee developed guidelines for authorship and a process for review and approval of manuscripts and abstracts prior to submission for publication or presentation.

Figure 1.

Prematurity and Respiratory Outcomes Program (PROP) Structure and Logo.

Additional funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) through the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA) allowed expansion of the database collection to include comprehensive medication administration data (in hospital and post-discharge) and the creation of a “PROP Scholars” program to fund competitive and innovative PROP-related subprojects for trainees and junior faculty.

Multicenter protocol development

Primary and secondary outcomes

A key scientific aim of PROP is to identify early clinical, physiologic, or biochemical biomarkers during the NICU hospitalization that can predict respiratory morbidity through 1 year of age. The primary outcome for PROP is the presence or absence of substantial post-prematurity respiratory disease, a composite obtained from longitudinal data in the first year post NICU discharge. Morbidity in four domains is examined: respiratory symptoms, medication use, hospitalizations and dependence on technology during the first year of life and results of infant pulmonary function testing at 1 year of age in a subset of participants. Mortality from cardiorespiratory cause is incorporated as well.

Secondary outcomes include death, near-term “BPD” status, the PROP Physical Exam Score and a Respiratory Morbidity Severity Score at one year, summarizing severity across the morbidity domains.

Protocol

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 2 and the protocol is outlined in Figure 2. The protocol is designed to provide the highest resolution phenotyping possible with the mandate to use standardized, widely applicable, non-invasive methods for data and biospecimen collections that will reflect a continuum of disease and care.

Table 2.

Inclusion/Exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | |

| - | 23 0/7 to 28 6/7 weeks using best obstetrical estimate |

| - | 7 days of age or less at enrollment |

| Exclusion criteria | |

| - | Concern for viability |

| - | Structurally significant congenital heart disease |

| - | Structural abnormalities of the upper airway, lungs or chest wall |

| - | Congenital malformations or syndromes that adversely affect life expectancy or cardio-pulmonary development |

| - | Family unlikely to be available for long-term follow-up |

Figure 2.

PROP Study Protocol Time Line spans from birth to one year of corrected age collecting health data and biospecimens. *Tracheal aspirate samples were collected if the infant was intubated and clinically required suctioning. #Physiologic challenge testing was either from oxygen to room air (21% oxygen, the “Room Air Challenge”) or from room air to 15% oxygen (“hypoxia challenge”) depending on status. NIRA: Non-invasive respiratory assessment; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; iPFT: infant pulmonary function testing.

The sample size for the multicenter study was pre-specified to include 750 surviving infants at a 36-week postmenstrual age (PMA) time-point. Power calculations consider a simplified binary outcome of persistent respiratory disease correlated with a continuous clinical, physiologic, or other biomarker. The sample size of 750, assuming a missing rate of 10% (5% due to late deaths and 5% due to loss to follow up), allows a power of >80% to detect a significant association at an odds ratio of 1.25 or higher for each one standard deviation increase in the biomarker associated with respiratory disease presence. This calculation assumes no measurement errors and no correlation between the biomarker and other covariates, and a conservative 40% rate of persistent respiratory disease.

Clinical data collection

All data are prospectively collected from birth using medical record review and family interviews and include: maternal and infant demographics, clinical data and co-morbidities, daily infant respiratory, nutritional, and medication data throughout the NICU stay. Mothers also provide family history of atopy and asthma (See data collection forms in Additional files 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6). After discharge, a series of telephone questionnaires, based on the Tucson Children’s Respiratory Study [2-6] and the Breathing Outcomes Study (a secondary study to the NICHD Neonatal Research Network Surfactant Positive Airway Pressure and Pulse Oximetry Trial) [7-9] are conducted. The questionnaires assess domains of respiratory morbidity at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months corrected age. At 6 and 12 months, a survey of environmental respiratory irritant exposures and an assessment for gastroesophageal reflux disease, using the modified Infant Gastroesophageal Reflux Questionnaire Revised, are completed [10]. An in-person visit for a physical exam and history is performed at 1 year corrected age. Families are also consented for continuing contact for anticipated longer-term studies.

Biospecimen archive

Gaps in our understanding of chronic and long-term respiratory sequelae of prematurity are widened by a general lack of clinically derived biospecimens to be used to identify biomarkers and mechanisms of disease. A sub-committee established standardized procedures for sample collection and central processing, and protocols for accessing the resulting biorepositories (Additional files 1 and 9). Samples collected are cross-sectional or longitudinal (Figure 2). Saliva specimens from infants and parents are collected at study entry for future DNA extraction. Saliva/mouth swabs obtain high quality infant DNA, but may require re-collection to achieve sufficient quantity for exome or genome-wide analyses (>5 micrograms of DNA). Tracheal fluid samples are collected if the infant is intubated and clinically requires suctioning. Tracheal aspirates and urine specimens are obtained on enrollment, 3 days after enrollment, and at 14 and 28 postnatal days. Early (≤1 week) specimens may reflect initial injury, developmental and genetic biosynthetic capacity and present the opportunity to intervene with a targeted therapy, while the later time points (>1 week) may reflect responses to oxidative stress, infection, inflammation, nutritional state, and tissue repair [11]. The DCC maintains details about the biospecimens for quality control and to assist in their identification for distribution. The Steering Committee formally defined a mechanism to submit and evaluate biospecimen access request proposals, with PROP-related investigative teams receiving short-term priority. Applications for access to the specimens will be reviewed for justification and feasibility of the proposed assays, and are expected to demonstrate independent funding to generate and analyze resulting data.

Assessments of respiratory function (physiologic biomarkers)

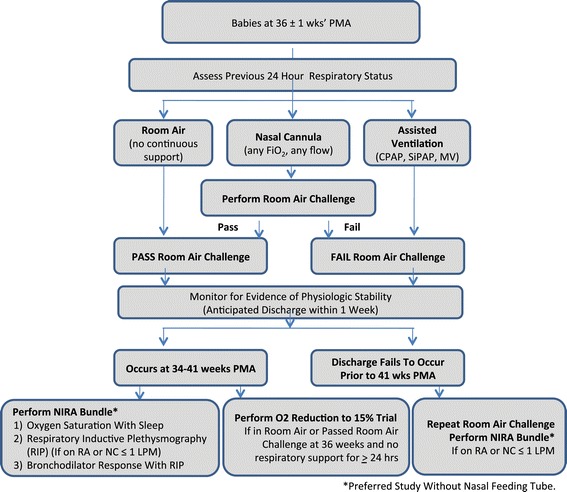

A unique feature of the PROP protocol is the inclusion of physiologic biomarkers as potential predictors of respiratory morbidity, based on the established value of premorbid respiratory function as an independent risk factor for wheezing and asthma in later life for term infants [2,5]. Standard infant pulmonary functions tests (PFTs) simulating adult-like spirometry can be performed during the first postnatal year but are not feasible in NICU. Additionally, these tests are time and labor intensive, and not easily performed on a large scale. As alternative measures for the entire cohort, a set of non-invasive respiratory assessments (NIRAs) was selected, including respiratory inductance plethysmography (RIP), pulse oximetry recordings during sleep, bronchodilator response, and oxygen reduction challenges (Figure 3, Table 3). The NIRAs are performed at 34–41 weeks PMA if the subject is not mechanically ventilated or receiving non-invasive positive pressure ventilation. Studies are performed within one week of anticipated discharge and, if possible, without a nasal feeding tube in place. The timing for pre-discharge testing is purposefully linked to anticipated discharge instead of a given gestational age as a reflection of achieved physiologic stability.

Figure 3.

Non-Invasive Respiratory Assessment (NIRAs) Decision Diagram. The indicated oxygen reduction tests and respiratory inductive plethysmography (RIP) (with associated tests of oxygen saturations during sleep and oral feeding) were preformed on individual days determined by corrected age, degree of respiratory support required and anticipation of hospital discharge.

Table 3.

PROP Noninvasive respiratory assessments (NIRA) and relationship to physiologic measures

| NIRA | Measurements | Potential mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory Inductance Plethysmography | Tidal breathing analysis | Altered lung compliance and airway obstruction |

| - Phase angle | ||

| - Tpef/Te | ||

| Desaturations after short apnea | Reduced functional residual capacity | |

| Response to inhaled albuterol | Increased smooth muscle tone | |

| - Phase angle | ||

| - Tpef/Te | ||

| Physiologic Challenges | Oxygen and flow reduction to ambient air | Alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient, control of breathing, standard definition of “BPD” |

| Hypoxic challenge test with 0.15 FiO2 | V/Q mismatch, control of breathing, “respiratory reserve” |

Specific NIRAs performed depend on the clinical status at the anticipated discharge date and include measurements of thoracoabdominal asynchrony and the ratio of time to peak tidal expiratory flow to expiratory time (Tpef/Te) using RIP [12-19]. To assess potential airway reactivity, RIP is performed before and after inhaled albuterol [12,19]. Continuous pulse oximetry data are obtained from quiet sleep during the RIP study and analyzed for the number and pattern of desaturations associated with spontaneous short (<20 sec) apneas. This non-invasive test indirectly infers that lung volume is adequate and can be maintained. Increased frequency of mild oxyhemoglobin desaturations with short apneas can reflect reduced functional residual capacity [19]. The PROP analysis assesses the number of episodes per minute of quiet sleep in which the oxygen saturation (SpO2) decreases 4% or more, the fall in SpO2 per second of apnea, and the lowest SpO2.

For comparison purposes with existing classifications of BPD [19-24], data regarding use of supplemental oxygen at 36 ± 1 weeks PMA and results of a standardized oxygen requirement challenge test are collected. If the infant fails the challenge test or is not eligible based on degree of respiratory support or clinical care team assessment of instability, and if the infant is still in the hospital, another assessment and challenge is attempted at 40 ± 1 weeks (Figure 3). The protocol developed by Walsh, et al. was modified to discriminate between effects of FiO2 and flow (the latter potentially generating stimulation or positive distending pressure, thus affecting oxygenation [23]). The infants are studied in quiet sleep at least 30 minutes after feeding. If oxygen saturations are maintained ≥90% for at least 15 minutes on the prescribed nasal cannula support, the FiO2 is weaned to 0.21 in decrements of 0.2 at 5-minute intervals. The flow is then reduced in 1 liter/min (LPM) decrements at 10-minute intervals until it is less than 1.5 LPM, followed by 50% decrements to a minimum of 0.125 LPM. After a 10-minute observation period, the cannula is removed and the infant is monitored in room air for 1 hour. Failure at any point in the testing is defined as SpO2 < 90% for 5 continuous minutes, SpO2 < 80% for 15 seconds, or apnea for >20 seconds. The latter, or bradycardia of <80 beats/min for >10 seconds, are recorded as adverse events. The infants are returned to the original support at the end of testing.

To further characterize the respiratory reserve of infants who are breathing ambient air or who pass a room air challenge test at 36 weeks, a 15-minute trial of FiO2 of 0.15 (the equivalent of the O2 partial pressure at 8000 feet altitude) was originally performed prior to discharge. This “hypoxia challenge” is recommended for individuals with cardiopulmonary conditions in anticipation of air travel [25,26]. After baseline data collection, if SpO2 was continuously ≥90%, a monitored respiratory oxyhood is placed over the sleeping infant with either a commercially available mixture of 15% oxygen with nitrogen or an on-site blended mixture of medical oxygen and nitrogen resulting in an FiO2 of 0.15. Criteria for failure of this test included SpO2 < 85% for 60 consecutive seconds, SpO2 < 80% for 15 seconds, bradycardia (HR <80 beats/min for 10 sec) or apnea persistent despite mild tactile stimulation. Interim review of results performed in 2013, demonstrated a test rate of 34% (221 of 643 discharged to home) and a failure rate of 78% with a median age of 36 weeks PMA at testing. Although no significant adverse events occurred, the high failure rate raised concerns about the ability of this challenge to provide additional insight into respiratory physiology and prompted the Observational Safety Monitoring Board to discontinue the hypoxia test in December 2013.

No severe adverse events (need for CPR or mechanical ventilation or increase in FiO2 by 0.1 above baseline) have occurred during any of the NIRA assessments. Four mild adverse events occurred during the study: one apnea (>20 seconds) with a RIP, and three bradycardia events, one with the hypoxia challenge and two with the room air challenge. No tachycardia (>200 beats per minute for >1 hour), or need for increase flow or FiO2 above baseline have occurred after any test.

Standardized physical examination

The Respiratory Distress Assessment Instrument (RDAI) and the Respiratory Assessment Change Score quantify responses to interventions in infants with wheezing [25-30] with good inter-observer reliability [31]. The PROP Physical Examination Score uses some elements of the RDAI and incorporates other elements that reflect the effects of chronic respiratory impairment, such as growth and the development of digital clubbing. This standardized physical exam focuses on anthropometrics, vital signs, and respiratory system signs and is performed coincident with RIP (36–40 weeks) and again at 1 year corrected age.

Examiners are all trained and certified to perform the standardized exam. With the infant in the supine position and awake, heart rate, respiratory rate and highest sustained oxyhemoglobin saturation are recorded over one minute. If the infant is still requiring supplemental oxygen (≤1.5 LPM) at the 12-month visit, the child is placed in room air for 2 minutes for measurement purposes only. End-inspiratory chest circumference, presence of suprasternal, intercostal or subcostal retractions, thoraco-abdominal asynchrony and accessory muscle use are recorded. Chest auscultation determines the presence, localization, and characteristics of crackles or wheezes. The cardiac point of maximal ventricular impulse is determined by palpation and the presence of digital clubbing is noted. Physical exam components are entered into single point and longitudinal algorithms as a composite score for later analysis.

Infant pulmonary function testing (iPFT)

Prematurity is associated with poorer lung function in infancy and childhood: even infants with minimal or no oxygen requirement at discharge demonstrate airflow obstruction and gas trapping compared to full-term controls [32-35]. To evaluate lung growth and respiratory dysfunction, six sites trained and certified to perform iPFTs will test 180 PROP infants. Infants eligible for iPFT receive chloral hydrate sedation to perform tidal breathing, single occlusion resistance/compliance measures, plethysmography and spirometry by the raised volume rapid thoracoabdominal compression (RVRTC) technique using the nSpire Infant Pulmonary Lab (nSpire, Inc, Longmont, CO) or BabyBox device (Carefusion Respiratory Diagnostics,Yoma Linda, CA) [36]. The raised volume technique is repeated after albuterol administration [37]. Measurements are listed in Additional file 8: Table S1. All techniques meet American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society standards [36,38-40]. Expert reading of the iPFT recordings is performed at two sites (Indiana University, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill).

Data collection, management and storage systems

A centralized Oracle database system (Oracle Corporation, Redwood Shores, CA) is maintained by the DCC. Local sites contribute data using a web-based interface. Individual centers retain access to their own data through customized downloads from Oracle that are transferred systematically to a REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) web-based database management tool [41]. In addition, some centers maintain an independent, customized, local REDCap database that is specific to their single site data acquisition. These data management options provide flexibility, separate layers of data quality control and simple and complete local access to Center specific data. The combination of a centralized database and local tools and storage result in a balance between the needs for a stable and secure core structure and flexible end-user applications.

Analytic approaches and considerations

The primary outcome of “post-prematurity respiratory disease” requires that infants demonstrate morbidity in one of the four post NICU discharge domains (respiratory medications; hospitalizations for cardiopulmonary cause; coughing, wheezing, or other respiratory symptoms; or home technology dependence) in at least 2 time frames (at approximately 3 month intervals). Death from a respiratory cause is also included. Secondary analyses will allow the modification of these criteria to assess the sensitivity of the chosen definition for the outcome. Alternate analyses will also consider a repeated measures analysis for the individual-visit level data using mixed effect logistic regression and generalized estimating equations.

Analysis approaches will include multiple individual statistical tests at the univariate and multivariate levels utilizing the accumulated clinical and physiologic data to evaluate potentially complex associations, to control for confounding factors, and to assess contributions to outcomes. Since the PROP is composed of 6 designated clinical research centers affiliated with a total of 13 NICUs, the analysis will be adjusted for clinical sites. The impact of significant missing data on outcomes will be assessed and reported in secondary analyses.

While in some cases it will be appropriate to provide some protection against detecting false positive results, adjustments of significance levels using multiple comparison techniques, which would lessen the chance of detecting potentially important biomarkers and other risk factors for severity of respiratory disease will be used sparingly [42]. These more liberal approaches to dealing with multiple comparisons were considered for hypothesis generating rather than hypothesis testing aims. Therefore, significance values related to odds ratios for biomarker prediction of the one-year outcome will generally be used as indicators for postulated risk factors.

Although PROP clinical sites are dispersed across the country, they may not be representative of NICUs in any defined geographic area. Known and measured factors that might impact the results will be assessed to examine factor imbalances within the PROP cohort and whether factor variations reflect the general population. The sensitivity of our approaches to changes in these factors will allow us to adjust or acknowledge discrepancies in any statements or inferences from PROP.

Study approval and oversight

The multi-center PROP protocol and consent forms were evaluated by the University of Pennsylvania IRB (initial approval date July 20, 2011) as a greater than minimal risk protocol due to the oxygen reduction testing and albuterol administration. In addition IRBs at each PROP center determined level of risk, based on their local interpretation. The IRBs further addressed issues of the future use of archived biospecimens, inclusion of an opt-in/opt-out approach for separate components of the protocol, including for DNA collection, and for future research, and methods to ensure subject privacy and protection. The program follows a strict monitoring plan for reporting adverse events and is monitored by an independent Observational and Safety Monitoring Board (OSMB) appointed by the Director of NHLBI. The complete list of IRB approvals and protocol numbers can be found in Appendix 2.

Training and quality control

Since study inception, the DCC has held bi-weekly training webinars with the research team from each site to ensure uniform approaches to data and specimen collection and respiratory assessments. Regular survey of the data by the DCC also permits targeted intervention at sites that may be facing challenges in executing some aspects of the protocol. In the early phases of enrollment, site visits by a team that included a PROP Principal Investigator, a consortium-identified lead research coordinator and lead respiratory therapist, pulmonologist, and representatives from NHLBI and the DCC reinforced these procedures and developed best practices to disseminate and maximize uniformity across the consortium, similar to that done with other complex multicenter protocols [43-45].

Interactions of single center and multicenter protocols

Each of the six non-DCC PROP Study Centers is responsible for a “single center” peer-reviewed project (Table 1). These projects share a common goal of identifying biomarkers of respiratory morbidity over the first year of life and an emphasis on preterm infants <29 weeks gestation. The common database of demographics, clinical NICU events, and respiratory examination and survey results reflecting 1-year outcomes can be used by each single center in the evaluation of their biomarker(s) of choice. Single center projects can recruit additional infants, including some born at >29 weeks and can obtain additional history or biospecimens not collected by the multicenter consortium. The Steering Committee decided that data and specimens relevant to a single center’s studies only would be entered and maintained locally.

Challenges and resolution

Several questions arose in the development and implementation of the study, all of which were brought to the Steering Committee for discussion and resolution. For example, delays and inconsistency in enrollment across sites prompted extensive examination of consent and enrollment procedures through webinars and site visits. Approaches based on the more successful centers’ practices were implemented and resulted in the targeted enrollment across the consortium.

As PROP investigators continue to formulate new ideas, the issue of who “owns” the multicenter data and specimens has also created tension regarding allocation of resources between the current needs of the PROP, such as analysis of existing data and publication of major outcomes, versus the need for preliminary data to develop funding proposals to pursue these new hypotheses. The Steering Committee decides on an individual basis how to balance these priorities. Access to biospecimens and linked data undergoes a similar review and prioritization process.

The maintenance of data and the biorepository beyond the PROP funding period are currently being resolved. As new funding proposals are developed that utilize collected biospecimens, support for personnel, specimen retrieval, and quality control procedures are being incorporated into the budgets and scientific plans.

Summary and progress through enrollment

Enrollment began August 3, 2011 and concluded November 1, 2013 (Figure 4); the follow-up to one year corrected age is expected to continue through mid-2015. Consent rates ranged from 42.4% to 80.9% by center, or 63.0% for the consortium, for a total enrollment of 835 participants. The most frequent reasons for exclusion or not approaching parents are highlighted in Figure 4. The demographics of the enrolled cohort are depicted in Table 4 and do not differ significantly from those not enrolled (data not shown).

Figure 4.

PROP Consort Diagram. * ‘Other’ reasons for not approaching parents for consent included maternal age and comprehension (9), parents objected to being approached for research (8), baby transferred less than 7 days (3), and screening oversight (3). ** ‘Other’ reasons for failure to consent included: language barrier (9), parent(s) overwhelmed (8), maternal illness (5), aged out prior to consent (4), baby died between consent discussion and decision (2), maternal comprehension (2), baby Illness (1).

Table 4.

Demographics of enrolled PROP multicenter cohort

| Enrolled a (N = 835) | |

|---|---|

| Birth weight, grams (mean +/− SD) | 900 +/− 240 |

| Gestational age, weeks (mean +/− SD) | 26.6 +/− 1.5 |

| - 23 weeks, 0–6 days | 34 (4%) |

| - 24 weeks, 0–6 days | 108 (13%) |

| - 25 weeks, 0–6 days | 129 (15%) |

| - 26 weeks, 0–6 days | 170 (20%) |

| - 27 weeks, 0–6 days | 201 (24%) |

| - 28 weeks, 0–6 days | 193 (23%) |

| Multiple gestation | 210 (25.1%) |

| - Twins | 171 (81%) |

| - Triplets | 35 (17%) |

| - Quadruplets | 4 (2%) |

| Male | 427 (51%) |

| Race b | |

| - Caucasian | 486 (58.2%) |

| - African American | 307 (36.8%) |

| - N. American Indian/Native Alaskan | 1 (0.1%) |

| - Asian | 20 (2.4%) |

| - Native Hawaiian/other Pacific islander | 1 (0.1%) |

| - Multi-race | 15 (1.8%) |

| - Other | 5 (0.6%) |

| Ethnicity b | |

| - Hispanic/Latino | 92 (11%) |

| Inborn | 728 (87.2%) |

| Outborn | 105 (12.6%) |

aPercentages may not add to 100 percent due to missing data for two babies who were withdrawn four days after enrollment.

bRace and ethnicity uses a mutually exclusive definition.

The biospecimen archive of DNA, tracheal aspirate and urine specimens, the physiologic testing, and breadth of the investigative teams prompted several ancillary studies that have added dimensions to the original PROP design (Table 5). Most notable was the development of the PROP Scholars’ program through support obtained from the NICHD BPCA program. This program’s major objective is to attract and retain pediatric physician scientists who are interested in pulmonary investigation. Through small competitive grants, trainees and non-NIH-funded junior faculty have access to learning opportunities otherwise not available and develop a time-limited research project that augments PROP single site studies (Table 5). Over 3 years, 12 individuals have been funded and afforded the opportunity to present their work at in-person steering committee meetings, as well as at national pediatric and pulmonary research meetings.

Table 5.

Ancillary projects arising from PROP

| Project | Center | Publications |

|---|---|---|

| PROP Scholars | ||

| Preventing attrition in follow-up | Penn | |

| Inter-rater reliability in physical exam | Penn | |

| Tracheal aspirate connective tissue mast cells in BPD | Rochester | [45] |

| Training in DLCO measurements | Rochester | |

| Treg impairment in preterm infants exposed to chorioamnionitis | Cincinnati | |

| Glutathionated hemoglobin as a biomarker for oxidant stress | Vanderbilt | [46] |

| RAGE signaling in BPD | Vanderbilt | |

| Periostin levels as a biomarker for BPD | Indiana | |

| Right ventricular strain measurements in evolving BPD | Washington U | [47-50] |

| Genetic contributions to BPD | UCSF | |

| Longitudinal lung clearance index measurements in premature infants | UCSF | |

| Oxidant stress and neurodevelopmental outcomes | Vanderbilt | |

| Variability in RIP | Washington U | [51] |

| Relationship between feeding desaturation, respiratory function and one year respiratory outcome in preterm infants | Rochester | |

| Respiratory pattern during physiologic challenges | Washington U | |

| RIP late preterm and term newborns | Rochester, Washington U | |

| Genetic Variants and Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Premature Infants | Multi-center |

Discussion

In summary, the current dissociation between the diagnosis of BPD and respiratory outcomes/pathogenesis of disease is due in part to a focus on hospitalization characteristics rather than longer-term outcomes. In reality, the continuum of disease and outcomes extend far beyond the neonatal period, and it is in this context that the respiratory consequences of prematurity need to be defined and evaluated. The PROP represents a significant investment by NHLBI to combine the multidisciplinary expertise of neonatologists, pediatric pulmonologists and basic scientists to provide a balanced analysis of disease and care of pulmonary disease of prematurity throughout the first year of life. The PROP will provide an understanding of mechanisms, evolution and consequences of lung disease in these preterm infants. It will also create a repository of genetic and biological samples that will provide the seeds of new hypotheses and future research in the complexity of gene-environment interactions.

Acknowledgements

Supported by National Institutes of Health, NHLBI and NICHD through U01 HL101794 to University of Pennsylvania, B Schmidt; U01 HL101456 to Vanderbilt University, JL Aschner; U01 HL101798 to University of California San Francisco, PL Ballard and RL Keller; U01 HL101813 to University of Rochester and University at Buffalo, GS Pryhuber, R Ryan and T Mariani; U01 HL101465 to Washington University, A Hamvas and T Ferkol; U01 HL101800 to Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, AH Jobe and CA Chougnet; and 5R01HL105702 to Indiana University and Duke University, CM Cotton, SD Davis and JA Voynow. In addition to the Principal Investigators, the authors would like to acknowledge the critical work of all PROP Site Investigators and research staff at each participating study Center as well as the lead coordinator, Julia Hoffmann, RN, at Washington University, and the lead respiratory therapy coordinator, Charles Clem, RRT, at Indiana University. The PROP logo was designed by R Dadiz. The authors would also like to acknowledge Carol J. Blaisdell, MD, Division of Lung Diseases, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA of NHLBI for her guidance and review of the manuscript as well as all the PROP Investigators (see Appendix 1) for their contributions to the design of individual and multicenter components.

Abbreviations

- BPD

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- DCC

Data coordinating center

- FiO2

Fraction of inspired oxygen

- iPFT

Infant pulmonary functions tests

- IRB

Institutional review board

- LPM

Liters per minute

- NHLBI

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- NICHD

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

- NICU

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- NIRA

Non-invasive respiratory assessments

- OR

Odds ratio

- OSMB

Observational safety monitoring board

- PI

Principal investigator

- PMA

Post menstrual age

- PMI

Point of maximal ventricular impulse

- PROP

Prematurity and respiratory outcomes program

- RDAI

Respiratory distress assessment instrument

- REDCap

Research electronic data capture

- RIP

Respiratory inductance plethysmography

- RVRTC

Raised volume rapid thoracoabdominal compression

- SC

Steering committee

- SpO2

Oxygen saturation

- Tpef/Te

Ratio of time to peak tidal expiratory flow to expiratory time

Appendix 1 Investigators and Research Staff

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Investigators

Claire Chougnet, PhD

Robert Frenk, MD

James M. Greenberg, MD

William Hardie, MD

Alan H. Jobe MD, PhD

Karen McDowell, MD

Research staff

Barbara Alexander, RN

Tari Gratton, PA

Cathy Grigsby, BSN, CCRC

Beth Koch, BHS, RRT, RPFT

Kelly Thornton BS

Washington University School of Medicine site

Investigators

Thomas Ferkol, MD

Aaron Hamvas, MD2

Mark R. Holland, PhD

James Kemp, MD

Philip T. Levy, MD

Phillip Tarr, MD

Gautam K. Singh, MD

Barbara Warner, MD

Research staff

Pamela Bates, CRT, RPFT, RPSGT

Claudia Cleveland, RRT

Julie Hoffmann, RN

Laura Linneman, RN

Jayne Sicard-Su, RN

Gina Simpson, RRT, CPFT

2Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

University of California San Francisco site

Investigators

Philip L. Ballard MD, PhD

Roberta A. Ballard MD

David J. Durand MD2

Eric C. Eichenwald MD 4

Roberta L. Keller MD

Amir M. Khan MD4

Leslie Lusk MD

Jeffrey D. Merrill MD 3

Dennis W. Nielson MD, PhD

Elizabeth E. Rogers MD

Research staff

Jeanette M. Asselin MS RRT-NPS2

Samantha Balan

Katrina Burson RN, BSN 4

Cheryl Chapin

Erna Josiah-Davis RN, NP3

Carmen Garcia RN, CCRP 4

Hart Horneman

Rick Hinojosa BSRT, RRT, CPFT-NPS 4

Christopher Johnson MBA, RRT 4

Susan Kelley RRT

Karin L. Knowles

M. Layne Lillie, RN, BSN 4

Karen Martin RN 4

Sarah Martin RN, BSN;

Julie Arldt-McAlister RN, BSN 4

Georgia E. McDavid RN 4

Lori Pacello RCP2

Shawna Rodgers RN, BSN 4

Daniel K. Sperry RN 4

2Children’s Hospital and Research Center Oakland, Oakland CA

3Alta Bates Summit Medical Center, Berkeley CA

4University of Texas Health Science Center- Houston, Houston TX

Vanderbilt University Medical Center site

Investigators

Judy Aschner, MD2

Candice Fike, MD

Scott Guthrie, MD3

Tina Hartert, MD

Nathalie Maitre, MD

Paul Moore, MD

Marshall Summar, MD4

Research Staff

Amy B Beller BSN

Mark O’ Hunt

Theresa J. Rogers, RN

Odessa L. Settles, RN, MSN, CM

Steven Steele, RN

Sharon Wadley, BSN, RN, CLS3

2Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx NY

3Jackson-Madison County General Hospital, Jackson TN

4Children’s National Health System, Washington DC

University of Rochester Medical Center/University at Buffalo NY site

Investigators

Carl D’Angio, MD

Vasanth Kumar, MD

Tom Mariani, PhD

Gloria Pryhuber, MD

Clement Ren, MD

Anne Marie Reynolds, MD, MPH

Rita M. Ryan, MD2

Kristin Scheible, MD

Timothy Stevens, MD, MPH

Research staff

Shannon Castiglione, RN

Aimee Horan, LPN

Deanna Maffet, RN

Jane O’Donnell, PNP

Michael Sacilowski, MAT

Tanya Scalise, RN, BSN

Elizabeth Werner, MPH

Jason Zayac, BS

Heidie Huyck, BS

Valerie Lunger, MS

Kim Bordeaux, RRT

Pam Brown, RRT

Julia Epping, AAS, RT

Lisa Flattery-Walsh, RRT

Donna Germuga, RRT, CPFT

Nancy Jenks, RN

Mary Platt, RN

Eileen Popplewell, RRT

Sandra Prentice, CRT

2Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston SC

Duke

Investigators

C. Michael Cotten, M.D.

Kim Fisher, Ph.D.

Jack Sharp, M.D.

Judith A. Voynow, M.D. 2

Research staff

Kim Ciccio, RN

2Virginia Commonwealth University

Indiana

Investigators

Stephanie Davis, MD

Brenda Poindexter, MD, MS 2

Research staff

Charles Clem, RRT

Susan Gunn, NNP, CCRC

Lauren Jewett, RN, CCRC

2Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

University of Pennsylvania, Perelman School of Medicine, DCC site

Investigators

Jonas Ellenberg, PhD

Rui Feng, PhD

Howard Panitch, MD

Barbara Schmidt MD, MSc

Pamela Shaw, PhD

Research staff

Maria Blanco, BS

Denise Cifelli, MS

Sara DeMauro, MD

Melissa Fernando, MPH

Ann Tierney, BA, MS

University of Denver, Steering Committee Chair

Lynn M. Taussig, MD

NHLBI program officer

Carol J. Blaisdell, MD

Appendix 2

Institutional Review Board Protocols at individual PROP sites

The University of Pennsylvania Data Coordinating Center – 813839

Cincinnati University Hospital (11) - 2011-1664

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (12) – 2011-1664

Cincinnati Good Samaritan’s Hospital (13) – 11139-11-084

Washington University (21) – 201104267

- University of California, San Francisco (31) – 10-04838

- Alta Bates (32) – 11-08-03

- CHO (32) –2011-050

University of Texas, Houston (33) – HSC-MC-11-0499

Vanderbilt University Monroe Caroll (41) - 110833

Jackson Madison County General Hospital (42) – 542

University of Rochester (51) – RSRB00037933

University of Buffalo (52) – 386479-1 DB # 2707

Duke University (61) – Pro 00025462

Indiana University (62) - 1201007831

Additional files

PROP biorepository lab specimen collection guideline.

Prematurity and respiratory outcomes program. Eligibility and baseline data.

Prematurity and respiratory outcomes program. Daily growth and nutrition/daily medication data.

Prematurity and respiratory outcomes program. Comorbidities of prematurity.

Prematurity and respiratory outcomes program. Standard visit and follow up surveys.

Prematurity and respiratory outcomes program. Additional medication log and miscellaneous forms.

Prematurity and respiratory outcomes program. Noninvasive respiratory assessments [NIRA].

Infant pulmonary function test measurements.

PROP biospecimen access policy.

Footnotes

Gloria S Pryhuber and Nathalie L Maitre contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AH and GP are Chair and Co-Chair, respectively, of the Writing Group responsible for this paper; AH, GP and NLM made substantial contributions to the drafting of the manuscript and revising it for intellectual content; AH/GP/RAB/SDD/JMG/JK/TJM/ HP/CR/JHE conceived significant portions of the study, made intellectual contribution to the study protocol, read and edited the manuscript; LT participated in study design and coordination and read and edited the manuscript; DC and PS made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data; all authors read and approved the final manuscript. The PROP Investigators as a group contributed to the design of the single site and multicenter studies. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Gloria S Pryhuber, Email: gloria_pryhuber@urmc.rochester.edu.

Nathalie L Maitre, Email: nathalie.maitre@vanderbilt.edu.

Roberta A Ballard, Email: BallardR@peds.ucsf.edu.

Denise Cifelli, Email: cifelli@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Stephanie D Davis, Email: sddavis3@iupui.edu.

Jonas H Ellenberg, Email: jellenbe@mail.med.upenn.edu.

James M Greenberg, Email: james.greenberg@cchmc.org.

James Kemp, Email: Kemp_J@kids.wustl.edu.

Thomas J Mariani, Email: Tom_Mariani@urmc.rochester.edu.

Howard Panitch, PANITCH@email.chop.edu.

Clement Ren, Email: clement_ren@urmc.rochester.edu.

Pamela Shaw, Email: shawp@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Lynn M Taussig, Email: lynn.taussig@du.edu.

Aaron Hamvas, Email: AHamvas@luriechildrens.org.

References

- 1.Maitre NL, Ballard RA, Ellenberg JH, Davis SD, Greenberg JM, Hamvas A, et al. Respiratory consequences of prematurity: evolution of a diagnosis and development of a comprehensive approach. J Perinatol. 2015; doi:10.1038/jp.2015.19 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Martinez FD, Morgan WJ, Wright AL, Holberg CJ, Taussig LM. Diminished lung function as a predisposing factor for wheezing respiratory illness in infants. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(17):1112–1117. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810273191702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez FD, Morgan WJ, Wright AL, Holberg C, Taussig LM. Initial airway function is a risk factor for recurrent wheezing respiratory illnesses during the first three years of life. Group Health Medical Associates. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143(2):312–316. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.2.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, Morgan WJ. Asthma and wheezing in the first six years of life. The Group Health Medical Associates. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(3):133–138. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501193320301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taussig LM, Wright AL, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, Morgan WJ, Martinez FD. Tucson Children’s Respiratory Study: 1980 to present. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(4):661–675. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright AL, Holberg C, Martinez FD, Taussig LM. Relationship of parental smoking to wheezing and nonwheezing lower respiratory tract illnesses in infancy. Group Health Medical Associates. J Pediatr. 1991;118(2):207–214. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)80484-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.SUPPORT Study Group of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Finer NN, Carlo WA, Walsh MC, Rich W, Gantz MG, et al. Early CPAP versus surfactant in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(21):1970–1979. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.SUPPORT Study Group of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Carlo WA, Finer NN, Walsh MC, Rich W, Gantz MG, et al. Target ranges of oxygen saturation in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(21):1959–1969. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens TP, Finer NN, Carlo WA, Szilagyi PG, Phelps DL, Walsh MC, et al. Respiratory outcomes of the surfactant positive pressure and oximetry randomized trial (SUPPORT) J Pediatr. 2014;165(2):240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleinman L, Rothman M, Strauss R, Orenstein SR, Nelson S, Vandenplas Y, et al. The infant gastroesophageal reflux questionnaire revised: development and validation as an evaluative instrument. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(5):588–596. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bose CL, Dammann CE, Laughon MM. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia and inflammatory biomarkers in the premature neonate. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2008;93(6):F455–F461. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.121327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen JL, Wolfson MR, McDowell K, Shaffer TH. Thoracoabdominal asynchrony in infants with airflow obstruction. Am RevRespir Dis. 1990;141(2):337–342. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Håland G, Carlsen KCL, Sandvik L, Devulapalli CS, Munthe-Kaas MC, Pettersen M, et al. Reduced lung function at birth and the risk of asthma at 10 years of age. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(16):1682–1689. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deoras KS, Greenspan JS, Wolfson MR, Keklikian EN, Shaffer TH, Allen JL. Effects of inspiratory resistive loading on chest wall motion and ventilation: differences between preterm and full-term infants. Pediatr Res. 1992;32(5):589–594. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199211000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris MJ, Lane DJ. Tidal expiratory flow patterns in airflow obstruction. Thorax. 1981;36(2):135–142. doi: 10.1136/thx.36.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmer J, Allen J, Mayer O. Tidal breathing analysis. NeoReviews. 2004;5:E186–E193. doi: 10.1542/neo.5-5-e186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sackner MA, Watson H, Belsito AS, Feinerman D, Suarez M, Gonzalez G, et al. Calibration of respiratory inductive plethysmograph during natural breathing. J Appl Physiol. 1989;66(1):410–420. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.1.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warren RH, Horan SM, Robertson PK. Chest wall motion in preterm infants using respiratory inductive plethysmography. Eur Respir J. 1997;10(10):2295–2300. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10102295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tourneux P, Leke A, Kongolo G, Cardot V, Degrugilliers L, Chardon K, et al. Relationship between functional residual capacity and oxygen desaturation during short central apneic events during sleep in “late preterm” infants. Pediatr Res. 2008;64(2):171–176. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318179951d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shennan AT, Dunn MS, Ohlsson A, Lennox K, Hoskins EM. Abnormal pulmonary outcomes in premature infants: prediction from oxygen requirement in the neonatal period. Pediatrics. 1988;82(4):527–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jobe AH, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(7):1723–1729. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2011060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ehrenkranz RA, Walsh MC, Vohr BR, Jobe AH, Wright LL, Fanaroff AA, et al. Validation of the National Institutes of Health consensus definition of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1353–1360. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walsh MC, Wilson-Costello D, Zadell A, Newman N, Fanaroff A. Safety, reliability, and validity of a physiologic definition of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Perinatol. 2003;23(6):451–456. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh MC, Yao Q, Gettner P, Hale E, Collins M, Hensman A, et al. Impact of a physiologic definition on bronchopulmonary dysplasia rates. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1305–1311. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samuels MP. The effects of flight and altitude. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89(5):448–455. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.031708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee Managing passengers with respiratory disease planning air travel: British Thoracic Society recommendations. Thorax. 2002;57(4):289–304. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.4.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klassen TP, Sutcliffe T, Watters LK, Wells GA, Allen UD, Li MM. Dexamethasone in salbutamol-treated inpatients with acute bronchiolitis: a randomized, controlled trial. J Pediatr. 1997;130(2):191–196. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(97)70342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowell DI, Lister G, Von Koss H, McCarthy P. Wheezing in infants: the response to epinephrine. Pediatrics. 1987;79(6):939–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schuh S, Coates AL, Binnie R, Allin T, Goia C, Corey M, et al. Efficacy of oral dexamethasone in outpatients with acute bronchiolitis. J Pediatr. 2002;140(1):27–32. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.120271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bueno Campana M, Olivares Ortiz J, Notario Munoz C, Ruperez Lucas M, Fernandez Rincon A, Patino Hernandez O, et al. High flow therapy versus hypertonic saline in bronchiolitis: randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(6):511–515. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-305443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCallum GB, Morris PS, Wilson CC, Versteegh LA, Ward LM, Chatfield MD, et al. Severity scoring systems: are they internally valid, reliable and predictive of oxygen use in children with acute bronchiolitis? Pediatr Pulmonol. 2013;48(8):797–803. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoo AF, Dezateux C, Henschen M, Costeloe K, Stocks J. Development of airway function in infancy after preterm delivery. J Pediatr. 2002;141(5):652–658. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.128114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friedrich L, Stein RT, Pitrez PM, Corso AL, Jones MH. Reduced lung function in healthy preterm infants in the first months of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(4):442–447. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200503-444OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhandari A, Panitch HB. Pulmonary outcomes in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Perinatol. 2006;30(4):219–226. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robin B, Kim YJ, Huth J, Klocksieben J, Torres M, Tepper RS, et al. Pulmonary function in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;37(3):236–242. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Thoracic S. European Respiratory S ATS/ERS statement: raised volume forced expirations in infants: guidelines for current practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(11):1463–1471. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200408-1141ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldstein AB, Castile RG, Davis SD, Filbrun DA, Flucke RL, McCoy KS, et al. Bronchodilator responsiveness in normal infants and young children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(3):447–454. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.3.2005080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castile R, Filbrun D, Flucke R, Franklin W, McCoy K. Adult-type pulmonary function tests in infants without respiratory disease. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2000;30(3):215–227. doi: 10.1002/1099-0496(200009)30:3<215::AID-PPUL6>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gappa M, Colin AA, Goetz I, Stocks J, ERS ATS Task Force on Standards for Infant Respiratory Function Testing Passive respiratory mechanics: the occlusion techniques. Eur Respir J. 2001;17(1):141–148. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17101410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stocks J, Godfrey S, Beardsmore C, Bar-Yishay E, Castile R, ERS ATS Task Force on Standards for Infant Respiratory Function Testing Plethysmographic measurements of lung volume and airway resistance. ERS/ATS Task Force on Standards for Infant Respiratory Function Testing. European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society. Eur Respir J. 2001;17(2):302–312. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17203020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22(4):719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davis SD, Rosenfeld M, Kerby GS, Brumback L, Kloster MH, Acton JD, et al. Multicenter evaluation of infant lung function tests as cystic fibrosis clinical trial endpoints. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(11):1387–1397. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200908-1236OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kerby GS, Rosenfeld M, Ren CL, Mayer OH, Brumback L, Castile R, et al. Lung function distinguishes preschool children with CF from healthy controls in a multi-center setting. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47(6):597–605. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhattacharya S, Go D, Krenitsky DL, Huyck HL, Solleti SK, Lunger VA, et al. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling reveals connective tissue mast cell accumulation in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(4):349–358. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0406OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ehrmann DC, Rose K, Calcutt MW, Beller AB, Hill S, Rogers TJ, et al. Glutathionylated gammaG and gammaA subunits of hemoglobin F: a novel post-translational modification found in extremely premature infants by LC-MS and nanoLC-MS/MS. J Mass Spectrom. 2014;49(2):178–183. doi: 10.1002/jms.3326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levy PT, Sanchez Mejia AA, Machefsky A, Fowler S, Holland MR, Singh GK. Normal ranges of right ventricular systolic and diastolic strain measures in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014;27(5):549. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Groh GK, Levy PT, Holland MR, Murphy JJ, Sekarski TJ, Myers CL, et al. Doppler echocardiography inaccurately estimates right ventricular pressure in children with elevated right heart pressure. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014;27(2):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levy PT, Holland MR, Sekarski TJ, Hamvas A, Singh GK. Feasibility and reproducibility of systolic right ventricular strain measurement by speckle-tracking echocardiography in premature infants. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26(10):1201–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh GK, Levy PT, Holland MR, Hamvas A. Novel methods for assessment of right heart structure and function in pulmonary hypertension. Clin Perinatol. 2012;39(3):685–701. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ulm LN, Hamvas A, Ferkol TW, Rodriguez OM, Cleveland CM, Linneman LA, et al. Sources of methodological variability in phase angles from respiratory inductance plethysmography in preterm infants. Ann Am Thor Soc. 2014;11(5):753–760. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201310-363OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]