Abstract

Aims

To perform a deterministic cost-utility analysis, from a 1-year societal perspective, of two treatment programs for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) without face-to-face contact: one Internet-based and one sent by post. The treatments were compared with each other and with no treatment.

Methods

We performed this economic evaluation alongside a randomized controlled trial. The study included 250 women aged 18–70, with SUI ≥ 1 time/week, who were randomized to 3 months of pelvic floor muscle training via either an Internet-based program including e-mail support from an urotherapist (n = 124) or a program sent by post (n = 126). Recruitment was web-based, and participants were self-assessed with validated questionnaires and 2-day bladder diaries, supplemented by a telephone interview with a urotherapist. Treatment costs were continuously registered. Data on participants' time for training, incontinence aids, and laundry were collected at baseline, 4 months, and 1 year. We also measured quality of life with the condition-specific questionnaire ICIQ-LUTSqol, and calculated the quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained. Baseline data remained unchanged for the no treatment option. Sensitivity analysis was performed.

Results

Compared to the postal program, the extra cost per QALY for the Internet-based program ranged from 200€ to 7,253€, indicating greater QALY-gains at similar or slightly higher costs. Compared to no treatment, the extra cost per QALY for the Internet-based program ranged from 10,022€ to 38,921€, indicating greater QALY-gains at higher, but probably acceptable costs.

Conclusion

An Internet-based treatment for SUI is a new, cost-effective treatment alternative. Neurourol. Urodynam. 34:244–250, 2015. © 2013 The Authors. Neurourology and Urodynamics published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: cost-effectiveness, Internet, pelvic floor muscle training, self-management, stress urinary incontinence

INTRODUCTION

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is the most common form of female incontinence.1 It has a prevalence of 10–35%1,2 and can affect quality of life in different ways.2 The first line of treatment is pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT), which leads to improvement or cure in about two-thirds of those affected.3,4 Despite effective treatment, only ∼20% of affected women seek care,5 possibly because leakage is not a major problem, but there are also women that avoid care because of embarrassment or shame.6 In addition, access to care might be limited and some women perceive they do not get any help when consulting their physician.6 Thus, there is a need for new, simple, and easily accessible treatments.4

Accessing the Internet for information on health issues is especially common among women.7 Internet-based treatments have been developed for several conditions, including headaches, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic pain, and obesity.8 Patients find Internet-based treatments to be convenient, flexible, and time-saving.9 The treatments can often be delivered at lowered costs because health care personnel can take care of more patients in parallel than in face-to-face treatments. For example, cost-effectiveness have been shown for Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for depression, panic disorders, and social phobia.10

The cost-effectiveness of a treatment or intervention is examined by comparing two alternatives, in regards to costs and effects. Costs are considered either from a health care perspective, that is, costs borne by the health care system, or from a societal perspective, which includes other costs. Effects are defined either by a pre-determined outcome, such as numbers cured, or by measuring quality of life to calculate quality adjusted life years (QALYs) gained or lost by a treatment. This second approach is called a cost-utility analysis and allows for comparison of diverse interventions.11

In this study, we performed a cost-utility analysis of two treatment programs for SUI without face-to-face contact: one Internet-based and one sent by post. The treatments are compared with each other and with no treatment.

METHODS

This is a deterministic cost-utility analysis, considered from a 1-year societal perspective, performed according to principles described by Drummond et al.11

Study Design and Population

We performed this economic evaluation alongside a randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing two different treatment programs for SUI. The RCT was registered at clinical trials (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, ID: NCT01032265) and has been reported in detail elsewhere.12 Briefly, 250 women, aged 18–70 with SUI at least once a week, were recruited via the project's website. After online screening and registration, the women were sent a postal self-assessed questionnaire for further evaluation, including a detailed medical history; validated questionnaires; and a 2-day bladder diary. GPs in the research team assessed all questionnaires and bladder diaries. Finally, a urotherapist interviewed all participants via telephone and confirmed the clinical diagnosis of SUI after a verbal assessment. Exclusion criteria were ongoing pregnancy, previous incontinence surgery, known malignancy in lower abdomen, difficulties with passing urine, macroscopic hematuria, intermenstrual bleedings, severe psychiatric diagnosis, and neurological disease with affection on sensibility in legs or lower abdomen. We consecutively randomized eligible participants to 3 months of treatment with either an Internet-based treatment program, or a treatment program sent by post. Both programs focused mainly on PFMT, but also contained information on SUI and associated life style factors, and training reports. The Internet group received individually tailored e-mail support from a urotherapist throughout the treatment period; whereas participants in the postal group completed training on their own. There was no face-to-face contact in either program. Follow-up data were collected at 4 months and 1 year after start of treatment.

Costs

Costs were evaluated from a 1-year societal perspective, that is, we included all relevant costs accrued during the first year, regardless of who paid for them. Costs for assessment included the printing and sending of questionnaires, mean time spent by the urotherapist for the telephone interviews, and the estimated time spent by the research assistant and general practitioners. Costs for treatment included the actual costs for domains, servers, administration, and service of the Internet-based program, and for the printing and sending of the postal program. In addition, the urotherapists registered the time spent with each participant in the Internet group. We did not include developmental costs for the programs.

At baseline and follow-up, we collected data from participants on their costs for incontinence aids and any extra laundry. We also asked if they had any other regular expenditure due to leakage (referred to as “other costs”) and to specify this. Data on time spent on PFMT were not available at baseline, but were collected during follow-ups. We assumed costs over the year would remain the same for the no treatment alternative as for the study population at baseline, and that no PFMT would be performed.

The gross hourly wages, including general payroll taxes, were known for the research assistant, the general practitioner, and the urotherapists. For the participants' time, we calculated a gross hourly wage based on the mean income for women with the same educational level in Sweden in 2010.13 Prices for incontinence aids were collected from the website of a large pharmacy brand in Sweden, (http://www.apoteket.se), and a price per unit was calculated using the mean consumption of the study population at baseline. Laundry prices were derived from the literature.14 Prices per unit were multiplied by the amount consumed and added up to a sum representing the total societal cost. All costs are given in Euros at the 2010 mid-year level.

Symptom Severity Groups

We measured symptoms with the validated questionnaire ICIQ-UI SF.15 The questionnaire contains three items on frequency, amount of leakage and overall impact on quality of life. Overall score is additive (0–21), with higher values indicating increased severity. The material was categorized into severity groups16 based on the baseline score (overall score 1–5 = slight, 6–12 = moderate, 13–18 = severe, 19–21 = very severe). In the statistical analyses, the groups severe and very severe were incorporated.

Quality of Life, Utility Weights, and QALYs

We used the validated condition-specific questionnaire ICIQ-LUTSqol17–19 to measure quality of life. The questionnaire contains 19 items on aspects of the quality of life that might be affected by leakage, such as the ability to work, travel, physical activity, family life, sexuality, mood, energy, and sleep. Each item is scored 1–4 (not at all/never, slightly/sometimes, moderately/often, a lot/all the time). The overall score is 19–76 with higher scores indicating greater impact. To calculate QALYs from the questionnaire, we used a preference-based index,20 where 9 of the 19 items are incorporated to create a health state classification. Using the algorithm of the index, we established syntax to translate the classification to a utility weight of 0 (representing the worst) to 1 (the best imaginable health state). For the no treatment alternative, we assumed that the quality of life, and thereby the utility weight, would be the same as the study population at baseline over the year.

Main Outcome

Our main outcome was the Incremental Cost Effectiveness Ratio (ICER) for each comparison. An ICER is calculated with the formula:

Three different ICERs were calculated: Postal treatment versus no treatment, Internet-based treatment versus postal treatment, and Internet-based treatment versus no treatment. Many women do not seek care for their leakage5 and we based the no treatment alternative on the assumption that participants in the RCT would not have sought other treatment if they had not been offered the study treatment programs.

Statistics

For baseline comparison of the intervention groups, we used the Student's t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Treatment effects within groups were analyzed using paired t-tests. For comparison of treatment effects between groups, we used a mixed model analysis. We previously described how overall scores in the ICIQ-LUTSqol were saved at baseline and in the 4 months follow-up.12 Occasional missing answers at 1 year follow-up were replaced with the corresponding answer at 4 months (n = 5). QALY changes were calculated using the “area-under-the curve”; whereas, costs were considered to change linearly.

Between the 4-month and 1-year follow-ups, five participants underwent surgery for their leakage (Internet group n = 2; Postal group n = 3). We included their data in the baseline and 4-month calculations, but not in the 1-year analysis. Means with 95% confidence intervals were determined for utility weights. We considered P-values of <0.05 statistically significant. Data were collected and analyzed in SPSS for Mac, version 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY) and in Excel for Mac, version 12.3.6 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA).

Sensitivity Analysis

To examine the stability of our results, we performed one-way sensitivity analysis where we varied the input data on time for PFMT, time for laundry, and cost for laundry, one at a time. We also performed a multi-way analysis where we incorporated all three of these variables at their lowest level.

For additional information, we performed a calculation for the base case scenario in a health care perspective.

Ethics

The Regional Ethical Review Board, Umeå University, provided ethical approval (number 08–124 M) of the study. All participants were thoroughly informed and provided their consent. We gave no reimbursements.

RESULTS

The study was conducted in Sweden from December 2009 to April 2011. A total of 250 participants were randomized to the treatments (Internet n = 124, Postal n = 126). A full description of the population has been published previously,12 but baseline characteristics such as age, education, smoking habits, symptom severity, and overall score in the ICIQ-LUTSqol are presented in Table I. There were no significant differences between the treatment groups in these measures.

Table I.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants in the RCT

| n = 250 | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean years (SD) | 48.6 (10.2) |

| Education at university level ≥3 years, n (%) | 135 (54) |

| Daily smoker, n (%) | 9 (3.6) |

| Symptom severity, n (%)a | |

| Slight | 14 (5.6) |

| Moderate | 170 (68.0) |

| Severe | 64 (25.6) |

| Very severe | 2 (0.8) |

| Overall score ICIQ-LUTSqol, mean (SD) | 33.6 (7.5) |

RCT, randomised controlled study; SD, standard deviation; ICIQ-LUTSqol, International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire-Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Quality of Life.

Based on overall score in the International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire-Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF).

At 4 months, we had lost 12.0% (30/250) of participants in follow-up (Internet 13.7% (17/124), Postal 10.3% (13/126), P = 0.44). At 1 year, 32.4% (81/250) were lost to follow-up (Internet 29.0% (36/124), Postal 35.7% (45/126), P = 0.28). Baseline measures on participants lost to follow-up, such as age, symptom severity and quality of life measures are presented in Table II.

Table II.

Age, Symptom Severity and Quality of Life Measures on Completers and Participants Lost to Follow-Up After 4 Months and 1 Year

| Completed follow-up 4 months, n = 220 | Lost to follow-up 4 months, n = 30 | P-Valuea | Completed follow-up 1 year, n = 169 | Lost to follow-up 1 year, n = 81 | P-Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline data | ||||||

| Age, years mean (SD) | 49.2 (10.2) | 44.2 (9.2) | 0.01 | 50.3 (10.1) | 45.1 (9.5) | <0.001 |

| Overall ICIQ-UI SF score, mean (SD) | 10.2 (3.2) | 11.9 (3.9) | 0.01 | 10.1 (3.2) | 10.9 (3.5) | 0.08 |

| Overall ICIQ-LUTSqol score, mean (SD) | 33.1 (7.3) | 37.2 (8.5) | 0.01 | 32.7 (6.8) | 35.5 (8.6) | <0.001 |

SD, standard deviation; ICIQ-UI SF, International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire-Urinary Incontinence Short Form; ICIQ-LUTSqol, International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire-Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Quality of Life.

Based on Student's t-test.

One woman in the Internet group reported lower abdominal pain when conducting PFMT and discontinued treatment, but no other side effects were reported.

Costs

The total assessment cost per participant was 14.9€. The cost for delivery of treatment was higher in the Internet-group (38.2€) compared to the postal group (6.6€). Total participants' costs (including time for PFMT, laundry, incontinence aids, and other costs) were higher in the postal program (574.7€), than in the Internet-based program (543.4€) and the no treatment alternative (274.0€). Examples of costs specified by the participants (i.e., “other costs”) were extra clothing and tampons for leakage protection. In Table III, we present the annual costs and their calculation per participant for each of the three alternatives.

Table III.

Costs Per Participant for Internet-Based Treatment, Postal Treatment, and no Treatment for Women With Stress Urinary Incontinence

| Units used | Cost | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price per unita | Internet-based treatment | Postal treatment | No treatment | Internet-based treatment | Postal treatment | No treatment | |

| Assessment | |||||||

| Printing and sending of questionnairesb | 4.0€ | 1 | 1 | — | 4.0€ | 4.0€ | — |

| Urotherapist's time for interview, mean (hr) | 27.2€ | 0.063 | 0.063 | — | 1.7€ | 1.7€ | — |

| General practitioner's time, mean (hr) | 57.6€ | 0.16 | 0.16 | — | 9.2€ | 9.2€ | — |

| Treatment delivery | |||||||

| Urotherapist's time, mean (hr) | 27.2€ | 1.35 | — | — | 36.8€ | — | — |

| Domains, servers, administration | 1.4€ | 1 | — | — | 1.4€ | — | — |

| Printing and sending of treatment programb | 6.6€ | — | 1 | — | . | 6.6€ | — |

| Participant's costs | |||||||

| Participant's time for PFMT, mean (hr) | 22.33€c | 19.51 | 20.20 | — | 435.7€ | 451.0€ | — |

| Participant's time for laundry, mean (hr) | 22.33€c | 1.87 | 1.95 | 5.59 | 41.8€ | 43.5€ | 125.0€ |

| Incontinence aids, mean (n) | 0.125€d | 268 | 334 | 377 | 33.5€ | 41.7€ | 47.1€ |

| Extra laundry loads, mean (n) | 2.1€e | 14.9 | 15.7 | 44.7 | 31.3€ | 32.9€ | 93.9€ |

| Other costsf, mean | 1.0€ | 1.1 | 5.6 | 8.0 | 1.1€ | 5.6€ | 8.0€ |

| Total cost | 596.5€ | 596.2€ | 274.0€ | ||||

PFMT, pelvic floor muscle training.

Prices are in Euros (€) at the 2010 mid-year level. Exchange rate 1 SEK = 9.62€.

Including 5 min of research assistant's time (24.95€ per hour).

Based on the 2010 mean income for Swedish women with similar educational levels (http://www.scb.se).

Based on mean consumption at baseline, prices from http://www.apoteket.se.

Subak et al.14

Any leakage-associated cost identified by the participant herself, for example extra clothing, tampons for leakage protection.

Improvement by Severity Group

Analysis by baseline severity (Internet and Postal groups incorporated) revealed that all severity groups improved significantly (P < 0.001) in symptom scores (ICIQ-UI SF) after 1 year. Condition-specific quality of life (ICIQ-LUTSqol) improved significantly (P < 0.001) in the groups with moderate (n = 117) and severe (n = 39) leakage but not in the group with slight (n = 11) symptoms.

Quality of Life, Utility Weights, and QALYs

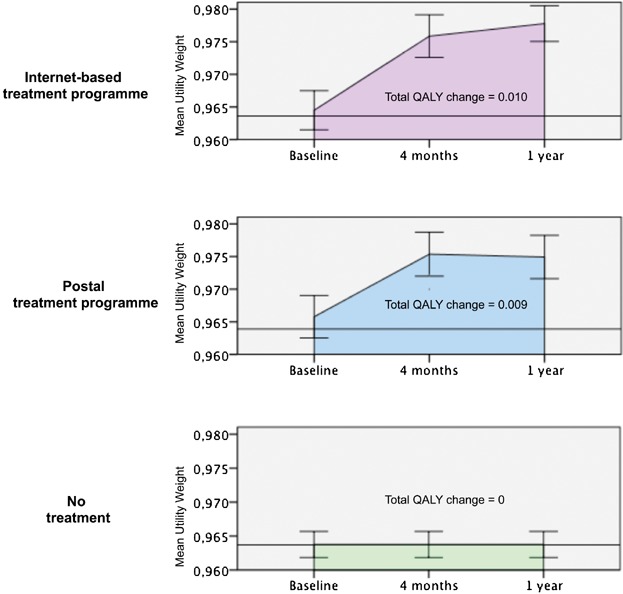

Within both treatment groups, we observed highly significant improvements (P < 0.001) in the overall scores in the ICIQ-LUTSqol at 4 months (mean change Internet 4.8 [SD 6.1], Postal 4.6 [SD 6.7]), and at 1 year (mean change compared with baseline; Internet 5.3 [SD 6.4], Postal 4.5 [SD 6.4]). The differences between the groups were not significant (P = 0.52 at 4 months, P = 0.79 at 1 year). The corresponding utility weights and QALY changes are presented in Figure 1. The QALYs gained correspond to an extra 3.7 days in the best imaginable health status for the Internet group and to 3.3 days for the postal group.

Fig 1.

Utility weights at baseline, 4 months, and 1-year follow-up with corresponding changes in quality adjusted life years (QALYs) for the Internet-based and postal treatments and no treatment option for stress urinary incontinence.

Main Outcome—ICERs—and Sensitivity Analysis

In Table IV, we present the ICERs for the base case and for the sensitivity analysis. In all analyses, the Internet-based and postal treatments had similar costs, but the Internet-based treatment was more effective. Compared to no treatment, the Internet-based treatment was more effective at higher costs.

Table IV.

Incremental Cost Effectiveness Ratios (ICERs) for the Internet-Based, Postal, and no Treatment Options, Including Base Case and Sensitivity Analysis

| Total cost (€a) | QALY-gain | ▵Cost (€) | ▵QALY-gain | ICERb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base case | |||||

| No treatment | 274 | 0 | 274 | 0 | — |

| Postal vs. no treatment | 596.2 | 0.0090 | 322 | 0.0090 | 35,905 |

| Internet-based vs. postal | 596.5 | 0.0104 | 0.3 | 0.0014 | 200 |

| No treatment | 274 | 0 | 274 | 0 | — |

| Internet-based vs. no treatment | 596.5 | 0.0104 | 322 | 0.0104 | 30,935 |

| Sensitivity analysis | |||||

| One-way: Participant's time for PFMT halved | |||||

| No treatment | 274 | 0 | 274 | 0 | — |

| Postal vs. no treatment | 371 | 0.0090 | 96 | 0.0090 | 10,757 |

| Internet-based vs. postal | 379 | 0.0104 | 8 | 0.0014 | 5,475 |

| No treatment | 274 | 0 | 274 | 0 | — |

| Internet-based vs. no treatment | 379 | 0.0104 | 104.4 | 0.0104 | 10,022 |

| One-way: Cost for laundry halved | |||||

| No treatment | 227 | 0 | 227 | 0 | — |

| Postal vs. no treatment | 580 | 0.0090 | 353 | 0.0090 | 39,337 |

| Internet-based vs. postal | 581 | 0.0104 | 1 | 0.0014 | 688 |

| No treatment | 227 | 0 | 227 | 0 | — |

| Internet-based vs. no treatment | 581 | 0.0104 | 354 | 0.0104 | 33,957 |

| One-way: Participant's time for laundry not included | |||||

| No treatment | 149 | 0 | 149 | 0 | — |

| Postal vs. no treatment | 553 | 0.0090 | 404 | 0.0090 | 38,713 |

| Internet-based vs. postal treatment | 555 | 0.0104 | 2 | 0.0014 | 1,490 |

| No treatment | 149 | 0 | 149 | 0 | — |

| Internet-based vs. no treatment | 555 | 0.0104 | 406 | 0.0104 | 38,921 |

| Multi-way: Participant's time for PFMT and cost for laundry halved, participant's time for laundry not included | |||||

| No treatment | 102 | 0 | 102 | 0 | — |

| Postal vs. no treatment | 311 | 0.0090 | 209 | 0.0090 | 23,257 |

| Internet-based vs. postal treatment | 321 | 0.0104 | 11 | 0.0014 | 7,253 |

| No treatment | 102 | 0 | 102 | 0 | — |

| Internet-based vs. no treatment | 321 | 0.0104 | 219 | 0.0104 | 21,029 |

QALY, quality adjusted life year; PFMT, pelvic floor muscle training.

€ = Euros at 2010 mid-year level.

ICER = ▵Cost/▵QALY-gain.

In the health care perspective, the ICER for postal versus no treatment was 2,400€/QALY, for Internet-based vs. postal treatment 21,787€/QALY, and for Internet-based versus no treatment 5,098€/QALY.

DISCUSSION

In this cost-utility analysis, we demonstrated that an Internet-based treatment program for SUI is cost-effective, from a 1-year societal perspective, compared to a postal treatment program and no treatment. The results are consistent and convincing even when costs are varied in different scenarios.

A major strength of this study is that costs and effects are based on known expenditures or actual measurements. An experienced research group conducted the RCT according to existing guidelines, and there were no interruptions or major problems during the study period. Loss to follow-up was low and similar in both groups. Also, the questionnaire used to measure quality of life is highly recommended by the International Continence Society21 and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).3

One limitation is that our participants were more highly educated than Swedish women in general; for example, 27% of Swedish women aged 25–64 years had a university education of 3 years or longer in 2010.13 The high educational level of our participants might have increased their capability to understand written instructions for PFMT and thereby enhanced the effect of treatment. Another limitation is that 32.4% of participants were lost to follow-up after 1 year, and that we lost more participants with high impact on quality of life at baseline. However, symptoms improved significantly in all severity groups, quality of life improved in all groups but one (slight, n = 11), and loss to follow-up was similar in both treatment groups. In our judgment, the risk for follow-up bias is little and this should not significantly affect the ratio of the comparisons or the order of magnitude of the ICERs. Furthermore, the ICIQ-LUTSqol has not previously been used for calculation of QALYs. However, the questionnaire is derived from the Kings Health Questionnaire (KHQ),17 which is widely used, and the method to calculate QALYs from the two questionnaires is identical.20

In cost-utility analysis, quality of life is often measured with health-specific questionnaires. However, it has been questioned whether these are sensitive enough to capture the full impact of SUI on quality of life,22 and methods to calculate QALYs from other types of quality of life questionnaires have been developed.20 In a condition-specific questionnaire designed for incontinence, only the leakage's impact on quality of life is taken into account, and consequently the derived utility weights are higher.20 The total QALY-gains in our study (Internet 0.010, Postal 0.009) are comparable to those found in studies using the KHQ. For example, in a study comparing the effect of three antimuscarinic drugs (fesoterodine, tolterodine, and solifenacin), the calculated QALY-gains were 0.01014, 0.00846, and 0.00957, respectively.23

The cost for the Internet-based program might be overestimated in our analysis. Our participants had increased wages due to their high educational levels; thus, the cost for participants' time would probably be lower in a clinical setting. In addition, the costs for domains, servers, and administration would be lower per participant in an enlarged setting. Moreover, in the no treatment alternative, effects might be overestimated as we considered the utility weight to remain unchanged over time, which probably is a conservative assumption. It is possible that instead a slight QALY-loss would occur because of increased prevalence and severity as the population grows older,1 even when considering that a spontaneous remission might take place in some cases.24

Our results were consistent in all scenarios. In the base case, we included the full time for participants' exercises, but PFMT can be performed while doing other things; therefore, it is likely that the time consumption decreases once the training is properly learned. Also, we found the time used on additional laundry was uncertain because dirty laundry caused by leakage might be washed together with other clothing. Furthermore, we considered the cost per laundry load derived from the literature as quite high for Swedish settings. Finally, we incorporated all of these uncertainties in a multivariate analysis, which might be more realistic.

It would have been interesting to compare the Internet-based and postal programs with a standardized face-to-face treatment or with care-as-usual. However, these alternatives would have introduced more uncertainty in the calculations and weakened the results. Also, care-as-usual differs depending on location and may consist of handing out brochures with self-instructions for PFMT. In our programs, the health care system's cost per participant was low (Internet 53.1€, Postal 21.5€). For comparison, in Sweden a GP consultation costs 173€,25 and in the UK, the cost for the National Health Service to deliver 3 months of PFMT supervised by a trained nurse is 158–293€ (£189–351).22 In a Dutch study, a 1-year care-as-usual alternative (including healthcare costs, patient's out-of-pocket, and travel costs, together with productivity losses) was calculated to 453€.26 This can be compared to the total cost for the Internet-based and the postal program of 596.5€ and 596.2€, respectively. However, the single largest entry in our study (436€–451€) was the cost of participants' time for PFMT, which was not included in the Dutch study. Without this entry, total costs for our programs would be substantially lower.

The extra cost per QALY for the Internet-based program ranged from 200€ to 7,253€ compared with the postal program and from 10,022€ to 38,921€ compared with no treatment. Whether these increased costs to deliver a more effective treatment are acceptable or not depends on the willingness-to-pay in society. In Sweden, an incremental cost per QALY  10,400€ (100,000 SEK) is considered low, and a cost

10,400€ (100,000 SEK) is considered low, and a cost  52,000€ (500,000 SEK) is considered high.27 These values are comparable with those from other countries, for example in the UK, where NICE usually recommends interventions with ICERs

52,000€ (500,000 SEK) is considered high.27 These values are comparable with those from other countries, for example in the UK, where NICE usually recommends interventions with ICERs  17,000–25,000€ (£20,000–30,000).22

17,000–25,000€ (£20,000–30,000).22

Although SUI might be distressful for the affected individual, it is not considered a severe medical problem and it is often given a low priority in times of high workload or financial constraint. In this study, we have shown that an Internet-based treatment for SUI is cost-effective compared with a postal program and no treatment. In the future, an Internet-based treatment for SUI could optimize the use of common resources and help unburden primary care. Most importantly, it could facilitate access to care for women that want treatment for their leakage.

CONCLUSION

An Internet-based treatment for SUI is a new, cost-effective alternative that could increase access to care for some women.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the women participating in the study. We appreciate all the work and effort of our urotherapists Eva Källström and Annika Andreasson, and research assistant Susanne Johansson. We are also thankful for the support from fellow PhD students and teachers at the National Research School of General Practice, funded by the Swedish Research Council. This study was supported by The Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research; the Jämtland County Council; the Västerbotten County Council (ALF); and Visare Norr, Northern County Councils, Sweden.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hannestad YS, Rortveit G, Sandvik H, et al. A community-based epidemiological survey of female urinary incontinence: The Norwegian EPINCONT study. Epidemiology of Incontinence in the County of Nord-Trondelag. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1150–7. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coyne KS, Kvasz M, Ireland AM, et al. Urinary incontinence and its relationship to mental health and health-related quality of life in men and women in Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Eur Urol. 2012;61:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Urinary incontinence: The management of urinary incontinence in women. London: RCOG Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shamliyan T, Wyman J, Kane RL. Nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in adult women: Diagnosis and comparative effectiveness. [Internet] Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); April 2012 (Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 36). Available at http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/169/834/urinary-incontinence-treatment-report-130909.pdf Accessed Dec 3, 2013.

- 5.Hannestad YS, Rortveit G, Hunskaar S. Help-seeking and associated factors in female urinary incontinence. The Norwegian EPINCONT Study. Epidemiology of Incontinence in the County of Nord-Trondelag. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2002;20:102–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milsom IAD, Lapitan MC, Nelson R. Epidemiology of urinary (UI) and faecal (FI) incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse (POP) In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, et al., editors. Incontinence 4th International Consultation on Incontinence, Paris July 5–8, 2008. 4th edition. Paris: Health Publication Ltd; 2009. pp. 35–113. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox S, Duggan M Health Online. 2013. Pew Research Center's Internet & American Life Project. [Internet] Washington, DC; 2013 (Updated January 15, 2013). Available from http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Health-online.aspx. Accessed Nov 27, 2013.

- 8.Andersson G, Ljotsson B, Weise C. Internet-delivered treatment to promote health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24:168–172. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283438028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferwerda M, van Beugen S, van Burik A, et al. What patients think about E-health: Patients' perspective on internet-based cognitive behavioral treatment for patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:869–73. doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hedman E, Ljotsson B, Lindefors N. Cognitive behavior therapy via the Internet: A systematic review of applications, clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;12:745–64. doi: 10.1586/erp.12.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sjostrom M, Umefjord G, Stenlund H, et al. Internet-based treatment of stress urinary incontinence: A randomised controlled study with focus on pelvic floor muscle training. BJU Int. 2013;112:362–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11713.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Statistics Sweden. Statistical database: Labour market; salary structure, whole economy. [Internet] Stockholm, Sweden; 2013 (updated June 20, 2013). Available from http://www.scb.se/Pages/SSD/SSD_TreeView.aspx?id=340478&ExpandNode=AM%2fAM0110. Accessed August 29, 2013.

- 14.Subak L, Van Den Eeden S, Thom D, et al. Urinary incontinence in women: Direct costs of routine care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:596.e1–9.-e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avery K, Donovan J, Peters TJ, et al. ICIQ: A brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23:322–30. doi: 10.1002/nau.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klovning A, Avery K, Sandvik H, et al. Comparison of two questionnaires for assessing the severity of urinary incontinence: The ICIQ-UI SF versus the incontinence severity index. Neurourol Urodyn. 2009;28:411–5. doi: 10.1002/nau.20674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelleher CJ, Cardozo LD, Khullar V, et al. A new questionnaire to assess the quality of life of urinary incontinent women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:1374–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coyne K, Kelleher C. Patient reported outcomes: The ICIQ and the state of the art. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:645–51. doi: 10.1002/nau.20911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sjostrom M, Stenlund H, Johansson S, et al. Stress urinary incontinence and quality of life: A reliability study of a condition-specific instrument in paper and web-based versions. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:1242–6. doi: 10.1002/nau.22240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brazier J, Czoski-Murray C, Roberts J, et al. Estimation of a preference-based index from a condition-specific measure: The King's Health Questionnaire. Med Decis Making. 2008;28:113–26. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07301820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abrams P, Avery K, Gardener N, et al. J Urol. 2006;175:1063–6. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00348-4. The International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire: http://www.iciq.net. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imamura M, Abrams P, Bain C, et al. Systematic review and economic modelling of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of non-surgical treatments for women with stress urinary incontinence. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14:1–188. doi: 10.3310/hta14400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arlandis-Guzman S, Errando-Smet C, Trocio J, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of antimuscarinics in the treatment of patients with overactive bladder in Spain: A decision-tree model. BMC Urol. 2011;11:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-11-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samuelsson EC, Victor FT, Svardsudd KF. Five-year incidence and remission rates of female urinary incontinence in a Swedish population less than 65 years old. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:568–74. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nilsson FO, Linner L, Samuelsson E, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of newer anticholinergic drugs for urinary incontinence vs oxybutynin and no treatment using data on persistence from the Swedish prescribed drug registry. BJU Int. 2012;110:240–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albers-Heitner CP, Joore MA, Winkens RA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of involving nurse specialists for adult patients with urinary incontinence in primary care compared to care-as-usual: An economic evaluation alongside a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:526–34. doi: 10.1002/nau.21204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. The National Board of Health and Welfare. National guidelines for methods of preventing disease. [Internet] Stockholm, Sweden; 2010. Available from http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2010/2010-10-15/Documents/halsoekonomiskt-vetenskapligt-underlag.pdf Accessed Nov 27, 2013.