Abstract

Objective

This multi-method, longitudinal study examines the negotiation of autonomy and relatedness between teens and their mothers as etiologic predictors of perpetration and victimization of dating aggression two years later.

Method

Observations of 88 mid-adolescents and their mothers discussing a topic of disagreement were coded for each individual’s demonstrations of autonomy and relatedness using a validated coding system. Adolescents self-reported on perpetration and victimization of physical and psychological dating aggression two years later. We hypothesized that mother’s and adolescents’ behaviors supporting autonomy and relatedness would longitudinally predict lower reporting of dating aggression, and that their behaviors inhibiting autonomy and relatedness would predict higher reporting of dating aggression.

Results

Hypotheses were not supported; main findings were characterized by interactions of sex and risk status with autonomy. Maternal behaviors supporting autonomy predicted higher reports of perpetration and victimization of physical dating aggression for girls, but not for boys. Adolescent behaviors supporting autonomy predicted higher reports of perpetration of physical dating aggression for high-risk adolescents, but not for low-risk adolescents.

Conclusions

Results indicate that autonomy is a dynamic developmental process, operating differently as a function of social contexts in predicting dating aggression. Examination of these and other developmental processes within parent-child relationships is important in predicting dating aggression, but may depend on social context.

Keywords: Adolescents, Dating aggression, Autonomy, Relatedness, Parental relationships

Aggression within dating relationships is a significant problem facing adolescents. A recent study using a US nationally representative sample found that 1 in 10 high school students reported physical dating violence victimization in the previous 12 months (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011). Rates of psychological aggression appear higher, with as many as 29% of adolescents in a nationally representative sample reporting victimization of psychological aggression in their relationships (Halpern, Oslak, Young, Martin, & Kupper, 2001). Although a few effective prevention programs have been developed and tested (Whitaker, Murphy, Eckhardt, Hodges, & Cowart, 2013), more needs to be understood about the etiological underpinnings of dating violence in order to move the prevention field forward. This study takes a unique approach to exploring the etiology of dating violence by exploring a developmental aspect of teens’ relationships with their mothers, specifically, the negotiation of autonomy and relatedness, as a longitudinal predictor of dating violence.

Research on the etiology of dating violence is in its early stages. Cross-sectional research has identified a wide range of potential risk factors for dating aggression, including demographic characteristics, cognitive/coping deficits, other risk behaviors, such as substance use and risky sexual behaviors, and family-level factors, such as witnessing violence among parents (Halpern et al., 2001; Lewis & Fremouw 2001; Silverman, Raj, Mucci, & Hathaway, 2001; Temple & Freeman, 2012). However, cross-sectional studies cannot distinguish correlates from true precipitating risk factors.. Longitudinal research is needed to establish temporal precedents of the onset of dating violence. A recent review by Vagi and colleagues (in press) of 20 longitudinal studies examined longitudinal risk and protective factors for perpetrating dating violence and identified 53 risk factors and 6 protective factors from both the individual and relationship levels. Overall, the longitudinal risk factor categories are similar to those discussed for correlational risk factors, and as with the cross-sectional risk factor literature, the majority of risk and protective factors were at the individual rather than relationship levels of the social ecology.

One theme that continues to emerge from both the cross-sectional and more recent longitudinal literature is that family-level variables play a key role in both the perpetration and victimization of teen dating violence. Certainly experiencing violence in the family (witnessing partner violence between parents and experiencing child abuse) is a well-established predictor of subsequent dating violence perpetration (Ehrensaft, et al, 2003; Lewis & Fremouw, 2001; Vagi et al, in press), but parental influence on dating violence behaviors seems to extend past exposure to violence. For instance, one study in Vagi and colleagues’ review found that a positive relationship with one’s mother was a protective factor for perpetration of dating violence (Cleveland, Herrera, & Stuewig, 2003), while another found that aversive family communication was a longitudinal risk factor for perpetrating physical violence (Andrews, Foster, Capaldi, & Hops, 2000). This paper further examines the role of family factors in the etiology of dating violence by examining how the negotiation of autonomy and relatedness of young adolescents with their mothers contributes to the prediction of teen dating violence by late adolescence.

Attachment and Autonomy as a Theoretical Framework

Attachment theory (Bowlby, 1982) asserts that the nature of relationships with caregivers influences children’s interactions and relationships throughout their lives and provides theoretical support for examining adolescents’ relationships with their parents in understanding subsequent relationships with their dating partners (McElhaney et al, 2009). Whereas the classic research on attachment in infancy focused on the child’s need for physical security, research on attachment in adolescence reflects a shift in focus to young people’s need for emotional or perceived security rather than for physical protection (Allen & Land, 1999). Whereas early operational definitions of adolescent autonomy in developmental research appeared instead to capture detachment from parents (Hill & Holmbeck, 1986), more recent work framed within attachment theory suggests that optimal growth in autonomy occurs in the context of a warm, emotionally supportive relationship with caregivers, using parents as a “secure base” from which to explore the world (Allen et al., 1997; McElhaney et al., 2009). Strivings for autonomy that occur in the context of warm and supportive parent-child relationships (ones high in relatedness) have been found to buffer adolescents from susceptibility to negative peer influence and involvement in delinquent behavior and contribute positively to the development of social skills (Allen, Chango, Szwedo, Schad, & Marston, 2012; Allen et al., 2002). However, adolescents’ strivings for autonomy in the absence of parental relationships characterized by a high degree of relatedness may actually be perceived as threatening the relationship and lead to an escalation of defensiveness, criticism, and other negative interactions within the relationship (McElhaney et al., 2009). Failure to successfully negotiate the task of establishing autonomy can have deleterious intra- and interpersonal consequences for youth outside of their relationships with parents, including low self-esteem (Allen, Hauser, Bell, & O'Connor, 1994), substance use (McElhaney et al, 2009), and violent behavior (Tate, 1999). Each of these outcomes has been associated with both perpetration and victimization of adolescent dating aggression (Foshee, Linder, MacDougall, & Bangdiwala, 2001; Malik, Sorenson, & Aneshensel, 1997; Vagi et al, in press). Therefore, it stands to reason that the negotiation of autonomy and relatedness with parents is a useful developmental process to investigate in the etiology of dating violence.

From Autonomy Development to Dating Aggression

The current study used data from a larger study examining attachment and autonomy and relatedness negotiation on a host of adolescent health, mental health and behavioral outcomes (Allen, McElhaney, Kuperminc, & Jodl, 2004). We examined observed interactions in which adolescents and their mothers sought to resolve personally relevant disagreements at age 16 and their potential associations with involvement in dating aggression two years later. Specifically, using an established coding system developed by the third author, observations of adolescents’ and their mothers’ behaviors relating to the promotion and inhibition of autonomy and relatedness exhibited during a discussion of a conflict in mid-adolescence were examined as predictors of adolescent self-report of perpetration and victimization of physical and psychological dating aggression in late adolescence. We examined the following hypotheses: 1) that mother’s demonstrations of supporting autonomy and supporting relatedness in their interactions with their teens would predict lower levels of perpetration and victimization of physical and psychological aggression two years later; 2) that mother’s demonstrations of inhibiting autonomy and inhibiting relatedness in their interactions with their teens would predict higher levels of teen’s perpetration and victimization of physical and psychological aggression two years later; 3) that adolescent’s demonstrations of supporting autonomy and supporting relatedness in their interactions with their mothers would predict lower levels of perpetration and victimization of physical and psychological aggression two years later; 4) that that adolescent’s demonstrations of inhibiting autonomy and inhibiting relatedness in their interactions with their mothers would predict higher levels of teen’s perpetration and victimization of physical and psychological aggression two years later. Because dating aggression has been demonstrated in some studies to differ depending on adolescent sex, race, and socioeconomic risk, we explored these variables as potential moderators.

Method

Participants

The data were drawn from a larger longitudinal sample of adolescents and their families (Allen, McElhaney, Kuperminc, & Jodl, 2004). The original sample was selected from the 9th and 10th grades of two public high schools based on the presence of any of four academic risk factors: a failing grade in a course, 10 or more absences per grading period, a history of grade retention, or a history of suspension. These criteria were used for the original study to capture a sizeable range of students who could be identified by academic records to have the potential for future academic and social difficulties (see Allen et al, 2004, for further information about sampling strategy and eligibility criteria). About half of the students of the two schools met at least one of these criteria and were eligible for participation in the study.

Of the original 179 families who consented to the study, 136 adolescents and their families completed the first wave of data collection, and of these, 133 (98%) completed the second wave approximately two years later. The three adolescents who dropped out between Wave 1 and Wave 2 did not differ from the sample on any demographic or study variables. The current study used data from the subsample of these 133 adolescents who indicated at Wave 2 that they had had at least one dating partner in the past year (n=91). Of these 91 adolescents, 10 were missing data on the autonomy and relatedness variables from the mother-adolescent video-taped interaction task. Of these 10, 7 cases were determined to be missing at random (i.e., video tape was compromised or uncodable rather than the task being refused by the participants; Allison, 2002). Autonomy and relatedness data were imputed for these 7 cases using the EM algorithm (Allison, 2002), resulting in a final study sample of 88.

Of the 88 adolescents in the sample, 55% identified as Caucasian, 44% identified as African-American, and 1 participant (1%) identified as Other (e.g., multi-racial). The sample was fairly evenly split by sex (48% female). The mean family income was just over $30,000 per year (M=$31,322, SD=$19,747). The majority (58%) of the adolescents were in 10th grade and were almost 16 (M=15.85, SD=.87) at Time 1 and 18 years of age (M=18.18, SD=1.11) at Time 2. Sixty percent indicated that they were currently dating a partner and 10% were engaged to their current dating partner at Time 2.

Procedure

Approximately 67% of the families of eligible adolescents agreed to participate. As part of the first wave of data collection, those families attended two 3-hour sessions (Visits 1 and 2) and were paid $105 (per family) for their time. Transportation and childcare were provided upon request. Consent from each family member was obtained at the beginning of Visit 1, and consent and confidentiality were reviewed at each subsequent visit. During each of the two Wave 1 visits, family members completed face-to-face interviews and a series of questionnaires with an interviewer in a private room. Additionally, family members participated in videotaped dyadic interactions. Referral lists containing information about various professional and community services were provided to participants at the end of each session.

Roughly two years later, families returned for the second wave of data collection. Again, two three-hour sessions were conducted (Visit 3 and Visit 4). However, parents attended only Visit 3, while the adolescent returned for both visits. Procedures were identical to those of Wave 1, except that adolescents were paid $65 while each parent was paid $50.

Variables

Demographic variables

Demographic variables including sex, race/ethnicity, and environmental risk were measured through mother and adolescent self-report during Wave 1. Adolescents reported their sex and race and the high school they attended. Mothers reported on annual household income and number of persons supported by this income. Since all except one of the participants identified either as Caucasian or African American, race/ethnicity was coded dichotomously as either minority or non-minority (the one participant who identified as “other” was coded as minority). This does not assume that all minority groups are homogenous, either between groups or within groups; instead it allows us to test whether the predictive effect of autonomy and relatedness on dating violence differs for those who are part of the Caucasian majority and those who are not (McElhaney & Allen, 2001). As in another study examining this sample (McElhaney & Allen, 2001), a dummy variable indicating environmental risk was computed; families were identified as living in conditions of environmental risk if their income fell at or below the 200% federal poverty line and their residence was classified as urban. Research documents that poor families and children who live in urban areas are at high risk for exposure to crime and other negative outcomes related to criminal activity (McLoyd, 1990), and crime rates in the recruitment area supported this assertion (McElhaney & Allen, 2001; Virginia Department of State Police, 1995). Thus, poverty coupled with living in an urban area is likely a better indicator of exposure to crime and environmental risk than poverty alone.

Autonomy and relatedness

Adolescents and their mothers participated in a revealed-differences task during Wave 1, in which they discussed an issue about which they disagreed. Typical topics included money (19%), grades (19%), household rules (17%), friends (14%), and brothers and sisters (10%); other possible areas included communication, plans for the future, alcohol and drugs, religion, and dating. Trained graduate students used the videotapes and transcripts to code the mother– adolescent interactions using the Autonomy and Relatedness Coding System (Allen, Hauser, Bell, McElhaney, & Tate, 1994). This coding system has demonstrated construct validity, and has been used in multiple studies of adolescent functioning (Allen, Hauser, Bell, & O'Connor, 1994; Allen et al., 2002; Allen et al., 2012; Tate, 1999).

Concrete behavioral guidelines were used to code both mothers’ and adolescents’ individual speeches on 10 subscales. Three subscales reflected behaviors promoting autonomy, including stating reasons related to one’s own or the other’s position and exhibiting confidence. Three subscales reflected behaviors promoting relatedness, including asking for additional information, making remarks that acknowledge and validate the other’s perspective, and exhibiting engaged listening. Two subscales reflected behaviors inhibiting autonomy, including recanting one’s own position, making overpersonalizing remarks (such as “you always say things like that), and pressuring the other to accept one’s position. Finally, two subscales reflected behaviors inhibiting relatedness, including ignoring or distracting behaviors, and making insulting/rude/hostile remarks. Scores for each individual in the dyad were used as separate indicators of relationship quality and functioning (Tate, 1999). Spearman-Brown reliabilities ranged from .70 to.86 for the subscales, indicating excellent interrater reliability (Allen, Hauser, Bell, Boykin, & Tate, 1994). Composite measures had moderate to strong internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha estimates for promoting autonomy and relatedness ranging between .70 to .81 and estimates for inhibiting autonomy and relatedness ranging between .57 and .81 (McElhaney & Allen, 2001; Tate, 1999).

Dating aggression variables

Adolescents’ self-report of perpetration and victimization of physical and psychological aggression with any dating partner in the past year was measured using the physical and verbal aggression subscales of the original Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979). Response sets were modified from the original version of the CTS so that, instead of asking the adolescent to report raw frequencies of behaviors, a 4-point scale was used (0=never, 1=once or twice, 2=several times, and 3=many times). Dating aggression experiences were assessed at Wave 2, when the adolescents were about 18 years old.

For perpetration of physical aggression against any partner in the past year, adolescents were asked “How often have you done this with one or more romantic partners in the past year?” about 11 physically aggressive behaviors, such as throwing something at them, kicking them, hitting them with an object, choking them and threatening them with a knife or gun. The physical aggression subscale was modified slightly from the original CTS in two ways: 1) one item (“hit or tried to hit [partner] with something”) was broken into two items (“Hit or tried to hit them with a belt, hairbrush, paddle, stick, or similar item” and “Hit or tried to hit them with a club, baseball bat, lamp, chair or similarly heavy object”); and 2) one item from the CTS-2 (Straus, Hamby, McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) was added (“Purposely burned or scalded them”-- slightly different word order than CTS-2) For victimization of physical aggression from any dating partner within the past year, adolescents were asked, “How often has one or more romantic partners done this with you in the past year?” about the same physically aggressive behaviors. Final scores were obtained by summing scores on the four-point frequency scale across behaviors. Because the physical aggression variables were positively skewed, square root transformations of the sum scores for perpetration and victimization were used.

For perpetration of psychological aggression against any partner in the past year, adolescents were asked “How often have you done this with one or more romantic partners in the past year?” regarding 6 psychologically aggressive behaviors, such as insulting or swearing at the person, threatening to hit or throw something at them, and destroying an object. For victimization of psychological aggression from any dating partner, adolescents were asked, “How often has one or more romantic partners done this with you in the past year?” regarding the same psychologically aggressive behaviors. Final scores were obtained by summing scores on the four point frequency scale across behaviors.

Analytic Strategy

We hypothesized that adolescents’ and their mothers’ promotion of autonomy and relatedness in their coded interactions would predict lower levels of self-reported perpetration and victimization of dating aggression (physical and psychological) two years later, and that their inhibition of autonomy and relatedness would predict higher levels of perpetration and victimization of dating aggression two years later. Hypotheses 1 and 2 pertain to mothers’ behaviors supporting and inhibiting (respectively) autonomy and relatedness during an interaction at Time 1 to predicting the adolescents’ involvement in dating aggression at Time 2. Hypotheses 3 and 4 pertain to the adolescents’ behaviors supporting and inhibiting (respectively) autonomy and relatedness during an interaction at Time 1 to predict the adolescents’ involvement in dating aggression at Time 2. For each hypothesis, four dating aggression variables (perpetration and victimization of both physical and psychological aggression) were examined. Further, sex, race/ethnicity and risk status were examined as moderators for each dependent variable within each hypothesis. The same analytic strategy employing multiple regression analyses was used to examine each hypothesis. For each regression equation, preliminary analyses were conducted to examine contributions of sex, race/ethnicity and environmental risk status to explained variance in each dependent variable. These demographic variables were retained in the final model only if preliminary analyses revealed significant main effects or interactions involving those variables. Final regression models included identified demographic variables, followed by inclusion of the relevant autonomy and relatedness variables, and then (if supported) inclusion of interaction terms. Overall regression models were interpreted only if significant. Significant interactions were probed to determine whether the individual slopes of the lines for each level of the moderator variable significantly differed from zero, following the procedures recommended by Aiken and West (1991).

Results

Means and standard deviations were calculated for each independent and dependent variable for the entire sample and for each group defined by the moderator variables examined in this study. Means, standard deviations, and independent samples t-tests are presented in Table 1 for boys and for girls, for minority and Caucasian participants, and for participants who were exposed to environmental risk and those who were not. Sex, racial/ethnic, and risk-level differences were found for several independent and dependent variables. Girls displayed significantly more behaviors both supporting and inhibiting autonomy in interactions with their mothers than boys did. Girls also reported higher rates of perpetration of both physical and psychological aggression than boys. The mothers of minority adolescents exhibited fewer behaviors supporting relatedness with their teens than the mothers of Caucasian participants. Minority adolescents demonstrated fewer behaviors both supporting and inhibiting autonomy and fewer behaviors supporting relatedness in their interaction tasks than their Caucasian counterparts. Finally, comparing teens exposed vs. not exposed to environmental risk, the mothers of environmentally at-risk teens used fewer behaviors supporting their teens’ autonomy than the mothers of teens who were not at risk. Additionally, at-risk teens demonstrated fewer behaviors both supporting and inhibiting autonomy and fewer behaviors both supporting and inhibiting relatedness. There were no significant differences between minority and Caucasian, nor between high risk and low risk adolescents on perpetration or victimization of physical or psychological aggression.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Independent and Dependent Variables, with T-Tests of Differences Based on Moderator Variables

| Variable | Sample | Sex | Race/Ethnicity | Risk Status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| N=88 | Girls n=42 |

Boys n=46 |

t | Minority n=40 |

Caucasian n=48 |

t | At-Risk n=29 |

Not at- risk n=59 |

t | |

| Mothers’ Behaviors | ||||||||||

| Supporting Autonomy | 2.68 (0.66) | 2.62 (0.58) | 2.74 (0.72) | 0.90 | 2.61 (0.65) | 2.74 (0.66) | 0.93 | 2.45 (0.74) | 2.79 (0.58) | 2.35* |

| Inhibiting Autonomy | 0.90 (0.44) | 0.86 (0.47) | 0.94 (0.41) | 0.90 | 0.93 (0.44) | 0.89 (0.45 | −0.56 | 0.89 (0.42) | 0.91 (0.46) | 0.17 |

| Supporting Relatedness | 2.03 (0.69) | 2.16 (0.65) | 1.91 (0.70) | −1.72 | 1.76 (0.56) | 2.26 (0.71) | 3.57* | 1.92 (0.63) | 2.09 (0.71) | 1.12 |

| Inhibiting Relatedness | 0.90 (0.64) | 0.88 (0.65) | 0.93 (0.63) | 0.35 | 0.89 (0.72) | 0.92 (0.58) | 0.18 | 0.77 (0.57) | 0.97 (0.66) | 1.38 |

| Teen’s Behaviors | ||||||||||

| Supporting Autonomy | 1.88 (0.90) | 2.14 (0.80) | 1.65 (0.93) | −2.62* | 1.44 (0.79) | 2.25 (0.83) | 4.67* | 1.38 (0.83) | 2.13 (0.84) | 3.97* |

| Inhibiting Autonomy | 0.83 (0.55) | 0.99 (0.59) | 0.70 (0.48) | −2.55* | 0.70 (0.41) | 0.95 (0.63) | 2.12* | 0.61 (0.45) | 0.95 (0.57) | 2.81* |

| Supporting Relatedness | 1.36 (0.63) | 1.42 (0.54) | 1.30 (0.71) | −0.92 | 1.15 (0.59) | 1.54 (0.61) | 3.00* | 1.09 (0.66) | 1.49 (0.59) | 2.94* |

| Inhibiting Relatedness | 1.13 (0.69) | 1.22 (0.75) | 1.05 (0.63) | −1.17 | 1.01 (0.57) | 1.23 (0.77) | 1.53 | 0.94 (0.55) | 1.22 (0.74) | 2.03* |

| Physical Aggression | ||||||||||

| Perpetration | 1.17 (3.65) | 2.19 (5.08) | 0.24 (0.64) | −2.47* | 1.83 (4.75) | 0.63 (2.29) | −1.55 | 2.07 (5.50) | 0.73 (2.29) | −1.27 |

| Victimization | 1.62 (2.92) | 1.77 (3.58) | 1.48 (2.19) | −0.46 | 2.06 (3.78) | 1.25 (1.92) | −1.29 | 2.14 (3.58) | 1.36 (2.53) | −1.19 |

|

Psychological

Aggression |

||||||||||

| Perpetration | 3.65 (4.22) | 5.10 (4.93) | 2.33 (2.93) | −3.15* | 3.86 (4.88) | 3.48 (3.63) | −0.42 | 3.01 (3.96) | 3.97 (4.34) | 0.99 |

| Victimization | 4.28 (3.88) | 4.83 (4.15) | 3.78 (3.58) | −1.29 | 4.15 (4.36) | 4.40 (3.47) | 0.30 | 3.96 (4.00) | 4.44 (3.84) | 0.55 |

Note:

Iindicates p<. 05

Bivariate correlational analyses were also conducted between independent and dependent study variables (Table 2). For ease of presentation, all correlation coefficients were multiplied by 100 and coefficients with absolute values greater than 21 were significantly different from zero. Not surprisingly, many of the autonomy and relatedness variables were significantly intercorrelated, as were all of the aggression variables. Consistent with expectations, mothers’ behaviors inhibiting relatedness were associated positively with adolescents’ reports of both perpetration and victimization of psychological aggression. Also consistent with expectations, adolescents’ behaviors inhibiting autonomy were associated positively with psychological perpetration. Contrary to expectations, however, mothers’ behaviors supporting autonomy were positively correlated with adolescents’ reports of perpetration of psychological aggression. Surprisingly, none of the autonomy and relatedness variables were significantly correlated with reports of perpetration or victimization of physical aggression.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations Between Study Variables

| Variable Name | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mom’s Supporting Autonomy |

-- | |||||||||||

| 2. Mom’s Supporting Relatedness |

26 | -- | ||||||||||

| 3. Mom’s Inhibiting Autonomy |

−07 | −39 | -- | |||||||||

| 4. Mom’s Inhibiting Relatedness |

−08 | −43 | 48 | -- | ||||||||

| 5. Teen’s Supporting Autonomy |

31 | 43 | −01 | 11 | -- | |||||||

| 6. Teen’s Supporting Relatedness |

24 | 55 | −16 | −10 | 45 | -- | ||||||

| 7. Teen’s Inhibiting Autonomy |

06 | −12 | 19 | 33 | 37 | 07 | -- | |||||

| 8. Teen’s Inhibiting Relatedness |

−20 | −37 | 31 | 42 | −02 | −35 | 58 | -- | ||||

| 9. Psychological Perpetration |

21 | 03 | 15 | 22 | 20 | 07 | 25 | 15 | -- | |||

| 10. Psychological Victimization |

00 | −04 | 07 | 25 | 03 | 05 | 09 | 19 | 74 | -- | ||

| 11. Physical Perpetration (transformed) |

18 | −01 | 12 | 04 | 06 | 05 | 01 | −04 | 68 | 53 | -- | |

| 12. Physical Victimization (transformed) |

05 | −09 | 13 | 16 | −08 | −09 | −06 | 00 | 56 | 68 | 57 | -- |

Note: All values multiplied by 100. Transformed correlation coefficients ≥ |21| are significant at p ≤ .05.

Regression Models

Girls were more likely than boys to report perpetration of both physical and psychological aggression across the models examined. Additionally, minority youth were more likely than Caucasian youth to report perpetration of physical aggression in all models except that examining maternal behaviors supporting autonomy and relatedness. Sex and minority status accounted for between 11 and 19% of the variance in dating violence variables.

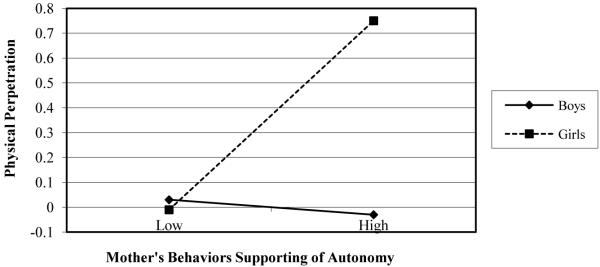

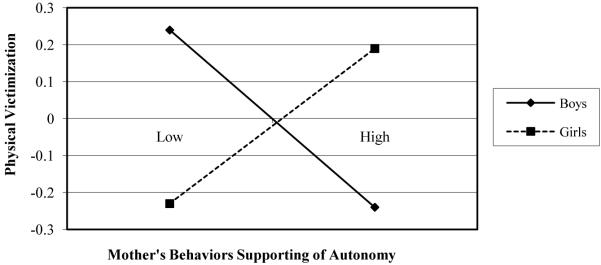

Hypothesis 1: Mothers’ Behaviors Supporting Autonomy and Relatedness as Predictors of Dating Aggression

The hypothesis that mothers’ behaviors supporting of autonomy and relatedness would negatively predict involvement in dating aggression was not supported (see Model 1, Table 3). Three of the four regression models examining maternal behaviors supporting autonomy and relatedness were significant, accounting for 13% to 28% of the variance. A significant interaction of sex with mothers’ behaviors supporting autonomy reached significance in two of those equations. Unexpectedly, in the models predicting perpetration of physical aggression, F(4,83) = 7.85, p<.05, and physical victimization, F(4,83) = 2.98, p<.05, the interaction terms uniquely accounted for 10 % and 11% of the variance, respectively, and indicated that maternal support for autonomy was associated with higher levels of dating violence for girls but not for boys (see Figures 1 and 2). The slopes of the lines for girls were significantly different from zero in the interactions predicting physical perpetration (ß = .65; p < .05) and physical victimization (ß = .50; p < .05), but the slopes of the lines for boys were not (ß = −.03 and −.24, respectively; ns). Finally, in the equation for perpetration of psychological aggression, F(3,84) = 6.05, p<.05, the significant main effect for maternal support for autonomy was contrary to the hypothesized direction, such that higher levels of maternal autonomy support predicted higher levels of psychological perpetration. The overall model of psychological victimization was not significant.

Table 3.

Final Models Multiple Regressions of Physical and Psychological Perpetration and Victimization with Mothers’ Behaviors Supporting and Inhibiting Autonomy and Relatedness

| Physical | Psychological | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perpetration β |

Victimization β |

Perpetration β |

Victimization β |

|

| Model 1 | ||||

| Sex | .37* | −.02 | .37* | .14 |

| Mother’s Behaviors Supporting Autonomy | −.03 | −.24 | .28* | −.20 |

| Mother’s Behaviors Supporting Relatedness | −.03 | .02 | −.11 | .02 |

| Mother’s Behaviors Supporting Autonomy x Sex | .41* | .45* | -- | .33* |

| R2 for Overall Model | .28* | .13* | .18* | .09 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Sex | .36* | -- | .34* | -- |

| Race/Ethnicity | .26* | -- | -- | -- |

| Mother’s Behaviors Inhibiting Autonomy | .15 | .07 | .08 | −.06 |

| Mother’s Behaviors Inhibiting Relatedness | −.02 | .12 | .20+ | .27* |

| R2 for Overall Model | .20 * | .03 | .17 * | .06 + |

Note:

indicates p < .05,

indicates p < .10.

Note: Sex is coded 0=male and 1=female; race/ethnicity is coded as 0=Caucasian and 1=African-American or other racial/ethnic minority

Figure 1.

Interaction between sex and standardized scores of mothers’ behaviors supporting of autonomy in predicting physical perpetration.

Figure 2.

Interaction between sex and standardized scores of mothers’ behaviors supporting of autonomy in predicting physical victimization.

Hypothesis 2: Mothers’ Behaviors Inhibiting Autonomy and Relatedness as Predictors of Dating Aggression

The hypothesis that mothers’ behaviors inhibiting autonomy and relatedness would positively predict involvement in dating aggression was not supported by the data (see Model 2, Table 3). The overall model predicting psychological perpetration was significant, but the regression weight for mothers’ behaviors inhibiting relatedness only approached statistical significance.

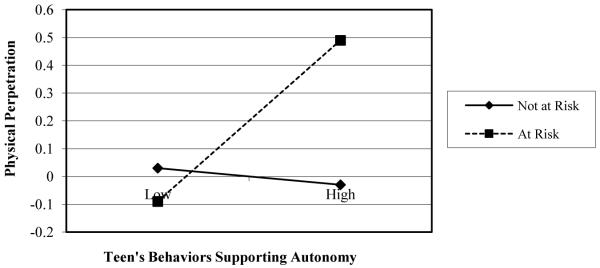

Hypothesis 3: Adolescents’ Behaviors Supporting Autonomy and Relatedness as Predictors of Dating Aggression

The hypothesis that adolescents’ behaviors supporting autonomy and relatedness would negatively predict involvement in dating aggression was not supported (see Model 1, Table 4). The model predicting perpetration of physical aggression reached significance and was predominantly characterized by the interaction of environmental risk with adolescents’ behaviors supporting autonomy. The overall model accounted for 25% of the variance in physical perpetration; the interaction term uniquely accounted for 5% of the variance in the model and indicated that at-risk adolescents demonstrating higher levels of support for autonomy reported higher levels of perpetration of physical aggression, whereas for low-risk participants, adolescent autonomy promotion did not affect reports of physical perpetration (see Figure 3). The slope of the line for at-risk participants was significantly different from zero (ß = .52, p < .05), but the slope for low-risk participants was not significant (ß = −.03, ns).

Table 4.

Final Multiple Regressions Models of Physical and Psychological Perpetration and Victimization with Adolescents’ Behaviors Supporting and Inhibiting Autonomy and Relatedness

| Physical | Psychological | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perpetration β |

Victimization β |

Perpetration β |

Victimization β |

|

| Model 1 | ||||

| Sex | .25* | -- | .27* | -- |

| Race/Ethnicity | .25* | .02 | .16 | -- |

| Risk Status | .20 | -- | -- | -- |

| Adolescents’ Behaviors Supporting Autonomy | −.03 | −.23 | .02 | .06 |

| Adolescents’ Behaviors Supporting Relatedness | .02 | −.11 | −.05 | −.08 |

| Adolescents’ Behaviors Supporting Autonomy x Race/Ethnicity | -- | .28+ | .29+ | -- |

| Adolescents’ Behaviors Supporting Autonomy x Risk Status | .32* | -- | -- | -- |

| R2 for Overall Model | .25 * | .05 | .18 * | .01 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Sex | .36* | −.02 | .28* | -- |

| Race/Ethnicity | .26* | -- | -- | -- |

| Risk Status | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Adolescents’ Behaviors Inhibiting Autonomy | −.001 | −.08 | .16 | −.03 |

| Adolescents’ Behaviors Inhibiting Relatedness | −.04 | .34+ | .02 | .21 |

| Adolescents’ Behaviors Inhibiting Relatedness x Sex | -- | −.38* | -- | -- |

| R2 for Overall Model | .19 * | .07 | .14 * | .04 |

Note:

indicates p < .05,

indicates p < .10.

Note: Sex is coded 0=male and 1=female; race/ethnicity is coded as 0=Caucasian and 1=minority; risk status is coded as 0=not at risk and 1=at risk.

Figure 3.

Interaction between risk status and standardized scores of adolescents’ behaviors supporting of autonomy in predicting physical perpetration.

Hypothesis 4: Adolescents’ Behaviors Inhibiting Autonomy and Relatedness as Predictors of Dating Aggression

The hypothesis that adolescents’ behaviors inhibiting autonomy and relatedness would positively predict involvement in dating aggression was not supported (see Model 2, Table 4). Adolescents’ behaviors inhibiting autonomy and relatedness were not significant predictors in any of the models.

Discussion

The current study was one of the first empirical attempts to prospectively predict dating aggression in late adolescence from observations of interactions with mothers two years earlier. The study employed a multi-method longitudinal design to examine hypotheses predicting main and interactive effects of autonomy and relatedness demonstrated in mother-adolescent interactions on later adolescent involvement in dating aggression. Whereas little evidence of main effects emerged, the primary findings indicate that the effects of autonomy promotion differ depending on the adolescent’s sex and level of risk. This finding is consistent with recent debates in the literature that we “need to move beyond simple ‘one size fits all’ main effects explanations of optimal autonomy processes. Although for the large majority of adolescents, autonomy development within the family appears to be a positive factor, this does not appear to be universally true” (Allen et al., 2002, p. 64). Unexpectedly, measures of relatedness had little or no prospective association with dating aggression. Moderation effects of sex and risk also indicate that adolescents’ negotiation of autonomy with parents and negotiation of dating relationships are dynamic processes that may operate differently for different adolescents.

Main Effects of Autonomy and Relatedness

Only one significant main effect of autonomy and relatedness emerged in models predicting a significant portion of the variance in dating violence, but it was contrary to hypotheses. Maternal support of autonomy was positively related to adolescent reports of perpetration of psychological aggression. This finding seems inconsistent with previous literature, which has found that mother’s support of autonomy is related to positive adolescent outcomes (Allen, et al., 1997), such as decreases in negative affect (Allen, et al., 1994) and parent-child conflict (Allen & Hauser, 1996), and increases in overall social functioning (McElhaney & Allen, 2001). More recent research suggests that high levels of support for autonomy may not always predict positive outcomes for all adolescents (Allen, et al., 2002; McElhaney & Allen, 2001), and the present finding may represent one of those instances. Further, it is possible that when adolescents report perpetration of psychological aggression, those behaviors may represent their attempts to exert autonomy within dating relationships, albeit in potentially maladaptive ways. Adolescents’ dating relationships may be characterized by uncertainty about individual roles (Feiring, 1999), and therefore may be a context in which adolescent dating partners are attempting to establish their own autonomy and independence with each other. An interesting direction for future research into this possibility would be to observe the promotion of autonomy and relatedness in interaction tasks between dating partners and assess whether autonomy struggles characterize the relational context of adolescents dating relationships in which psychological aggression is present. Qualitative methodologies could be used to assess the meaning adolescents attach to these behaviors and their reasons for perpetrating psychological aggression and to investigate whether they are linked to attempts to establish independence within the relationship. If so, prevention efforts could build skills around more productive ways to establish a sense of autonomy in the context of dating relationships.

Moderation Effects of Sex and Risk

The significant interactions of sex and risk status with behaviors supporting autonomy explained substantial amounts of variance in physical dating aggression. Although it was hypothesized that mothers’ behaviors supporting autonomy and relatedness would negatively predict adolescent involvement in physical dating aggression, for girls, the direction of the effect was opposite of the expected effect. It is possible that girls may interpret the meaning of the physically violent behaviors differently than boys, or that they are more likely than boys to report behaviors that happened in the context of playfighting or defending themselves than boys. If so, this could affect the impact of maternal support for autonomy on their reports of physical violence. It is also possible that these results may be explained at least in part by considering social norms regarding gender roles in intimate relationships. Gilligan (1982) suggests that boys tend to respond to images of relationships first in terms of their independence and autonomy, while girls think of relationships first in terms of their connectedness to others, and that society may reinforce these different ways of approaching relationships through social norms. Other researchers have noted that adolescence is a time of intensified adherence to gender norms and stereotypes (Hill & Lynch, 1983), and this process may be particularly salient when adolescents are forming new relationships (Feiring, 1999). Therefore, girls whose mothers have encouraged and supported autonomy in their daughters may find themselves in dating relationships where their autonomy is not supported by their dating partner or may even be discouraged due to gender role expectations. If this is the case, then increased levels of perpetration and victimization of physical aggression may be due to conflict arising from girls’ attempts to establish autonomy in relationships where their dating partners have conflicting expectations. It is important to note that sex did not moderate the relation between adolescents’ support for autonomy and physical perpetration or victimization. For girls, there appears to be something specific about the maternal encouragement of autonomy, rather than the girls’ own behaviors pertaining to autonomy, that predict increases in physical perpetration and victimization. Investigation of this interesting pattern is an important goal for future research in this area.

Also contrary to hypotheses, at-risk participants who demonstrated high levels of autonomy promotion with their mothers reported higher levels of perpetration of physical aggression against their dating partners two years later, while adolescent autonomy support did not affect reports of perpetration for low risk participants. Again, it is possible that the meaning of these physically violent behaviors may be different for at-risk participants than their less risky counterparts, and this could affect the impact of autonomy strivings on physical violence. Another possible explanation is that the effects of the task of autonomy negotiation vary according to the ecological and social context in which the parent-adolescent relationship exists. Research suggests that economically at-risk parents have different parenting styles than parents who live in more low-risk environments; these different styles may be necessary or at least reasonable adaptations to economic hardship, neighborhood danger, and other life stressors (Barrera et al., 2002; McLoyd, 1990). Parents in environmentally at-risk families are more likely to employ an authoritarian parenting style in raising their children, which is characterized by high levels of parental control, high demand for obedience, little allowance for child autonomy, and low parental warmth (Baumrind, 1972; Steinberg, et al., 1991). Although much research suggests that the authoritative parenting style (characterized by encouragement for the child’s autonomy and parental warmth within the context of firm rules) is more advantageous than the authoritarian parenting style common in these at-risk families, these effects are strongest for middle-class white families; the effect of the authoritarian style on negative child and adolescent outcomes has been found to be either weak or non-existent within high risk families (Baumrind, 1972; Steinberg, et al., 1991). Many suggest that the demand for obedience and lower promotion of autonomy in the authoritarian parenting style is actually an adaptive response to the more dangerous contexts in which some at-risk families live (Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Howard, Kaljee, Rachuba, & Cross, 2003). This explanation is empirically supported by the findings of McElhaney and Allen (2001) in a study with the same sample; they found that, for high-risk adolescents, maternal inhibiting of autonomy was related to positive mother-child relationship quality, while adolescent promotion of autonomy was related to higher delinquent behavior and lower mother-child relationship quality. These findings suggest that autonomy promotion may put adolescents at greater risk when they live in more risky environments and that inhibition of autonomy may represent conscious, strategic, and adaptive decisions to reduce levels of risk.

In sum, the moderation effects in this study suggest the need to examine the social, ecological, and contextual factors influencing the lives of adolescents in developmental research on adolescent dating aggression. Biological sex and environmental risk are merely markers of ‘social address’ (Bronfenbrenner, 1988) that have limited value in and of themselves, but serve to alert us to underlying social, environmental, and contextual factors that exist in the macrosystems in which adolescents live. The moderation findings could indicate both meaningful differences in autonomy processes for different groups and/or meaningful differences in the use/nature of aggression across groups.

Strengths and Limitations

This study contributes to the literatures on the development of autonomy and relatedness and on adolescent dating aggression. This is one of the first studies to examine the parent-adolescent relationship as a predictor of dating aggression. Furthermore, its longitudinal design adds to the primarily cross-sectional literature examining correlates of adolescent dating aggression, and its multi-method approach contributes to a literature on adolescent dating aggression that is primarily characterized by self-report surveys. Longitudinal and multi-method designs are time-intensive and difficult to execute, but they provide very rich data with which to examine complex phenomena such as dating aggression.

An additional strength of the study is as the examination of demographic moderators of the pathways to aggression, which sheds further light on potential differences in the meaning of and pathways to aggressive behavior within different groups of adolescents. Further investigation is needed into potential differences in the meaning of aggression and the reasons for use of aggression among different groups of adolescents. For instance, if girls and boys are reporting similar amounts of aggression, but have different interpretations of the behaviors or are perpetrating aggression for different reasons (self-defense, to establish independence), then a different intervention strategy is needed for girls than for boys who might be perpetrating aggression for a different reason. Future research should employ qualitative and quantitative methods to explore adolescents’ reasons for perpetrating aggression and the implications and consequences of aggression for different groups of adolescents.

An important limitation is the study’s small sample size, which limits both generalizability and statistical power, allowing for the detection of only large effect sizes (Cohen, 1992). Additionally, the current sample was purposefully recruited to be at-risk for academic failure, further limiting generalizability. Due to limited statistical power, other potentially relevant variables could not be included in analyses, such as the influence of peers and relationships with peers on the development of romantic relationships (Connolly & Goldberg, 1999) and dating aggression. Further, this study did not assess sexual dating violence, which is an important aspect of teen dating violence. Finally, this study was able to examine autonomy and relatedness only in mother-adolescent interactions, due to limited availability of data from father-adolescent dyads. Future studies with larger and more representative samples could examine the various contributions of these and other potentially important variables (e.g., violence exposure, substance use) in pathways to adolescent dating aggression. Finally, although the longitudinal design allowed us to examine pre-existing factors that may have led to involvement in dating aggression, the lack of experimental design precludes causal inference.

Research Implications

Further research is needed to fully understand the developmental, interpersonal, and psychosocial precursors of adolescents’ involvement in dating aggression, both as perpetrators and as victims. Such precursors may operate differently for different subsets of adolescents whose sex and environmental risk create different contexts from which they approach relationships. Similarly, research on autonomy and relatedness is shifting away from a universal hypothesis about the predictive power of these developmental constructs and is beginning to investigate the ways in which they operate differently for adolescents in various contexts. Considerations for future prevention research include examination of 1) parent- and peer-related developmental processes as precursors to adolescent dating aggression; and 2) demographic and contextual moderators in examinations of the meaning and predictors of dating aggression.

Prevention and Policy Implications

Understanding the relevance of developmental constructs in adolescent involvement in dating aggression and potential ecological variations in these constructs is critical to the development and implementation of prevention efforts. By understanding potential variations in processes that lead to dating aggression, there is a greater likelihood that prevention approaches can be effectively tailored for diverse groups of adolescents. As states increasingly pass legislation directing schools to implement dating violence prevention programs, it is critical that 1) we continue to develop interventions that are sensitive to variations in the etiology of dating aggression, and that 2) that policy makers and school administrators are aware the pathways to dating aggression may differ across adolescents and that prevention strategies may not be equally effective for all.

The effective prevention of dating aggression across a diversity of adolescent populations is critical to the prevention of intimate partner violence across the lifespan. Etiological research and the development of prevention strategies must recognize the different contexts in which adolescents live and how these contexts influence can differentially influence development of dating aggression.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Contributor Information

Phyllis Holditch Niolon, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Gabriel P. Kuperminc, Georgia State University

Joseph P. Allen, The University of Virginia

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Chango J, Szwedo D, Schad M, Marston E. Predictors of susceptibility to peer influence regarding substance use in adolescence. Child Development. 2012;83(1):337–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01682.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hauser ST. Autonomy and relatedness in adolescent-family interactions as predictors of young adults' states of mind regarding attachment. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:793–809. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hauser ST, Bell KL, Boykin KA, Tate DC. Autonomy and relatedness coding system manual. 1994 version 2.0. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hauser ST, Bell KL, O'Connor TG. Longitudinal assessment of autonomy and relatedness in adolescent-family interactions as predictors of adolescent ego development and self-esteem. Child Development. 1994;65:179–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hauser ST, Eickholt C, Bell KL, O'Connor TG. Autonomy and relatedness in family interactions as predictors of negative adolescent affect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1994;4:535–552. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Land D. In: Attachment in adolescence. Handbook of attachment theory and research and clinical applications. Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Guilford; New York: 1999. pp. 319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Marsh P, McFarland C, McElhaney KB, Land D, Jodl KM, et al. Attachment and autonomy as predictors of the development of social skills and delinquency during midadolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:56–66. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.70.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, McElhaney KB, Kuperminc GP, Jodl KM. Stability and change in attachment security across adolescence. Child Development. 2004;75:1792–1805. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00817.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Moore CM, Kuperminc GP. Developmental approaches to understanding adolescent deviance. In: Luthar SS, Burack JA, Cicchetti D, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Perspectives on adjustment, risk, and disorder. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1997. pp. 548–567. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing Data. Sage Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Foster SL, Capaldi D, Hops H. Adolescent and family predictors of physical aggression, communication, and satisfaction in young adult couples: A prospective analysis. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(2):195–208. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera J, Prelow HM, Dumka LE, Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Michaels ML, et al. Pathways from family economic conditions to adolescents' distress: Supportive parenting, stressors outside the family, and deviant peers. Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:135–152. M. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. An exploratory study of socialization effects on black children: Some black-white comparisons. Child Development. 1972;43:261–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Basic Books; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Interacting systems in human development. Research paradigms: Present and future. In: Bolger N, Caspi A, Downey G, Moorehouse M, editors. Persons in context: Developmental perspectives. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1988. pp. 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2011. 2011;61:4. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Surveillance Summaries. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland HH, Herrera VM, Stuewig J. Abusive males and abused females in adolescent relationships: Risk factor similarity and dissimilarity and the role of relationship seriousness. Journal of Family Violence. 2003;18(6):325–339. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, Goldberg A. Romantic relationships in adolescence: The role of friends and peers in their emergence and development. In: Furman W, Brown BB, Feiring C, editors. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1999. pp. 266–290. [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, Johnson JG. Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:741–753. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C. Gender identity and the development of romantic relationships in adolescence. In: Furman W, Brown BB, Feiring C, editors. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1999. pp. 211–323. [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Linder F, MacDougall JE, Bangdiwala S. Gender differences in the longitudinal predictors of adolescent dating violence. Preventive Medicine. 2001;32:128–141. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan C. In a different voice: Psychological theory and women's development. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Oslak SG, Young ML, Martin SL, Kupper LL. Partner violence among adolescents in opposite-sex relationships: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1679–1685. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.10.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J, Lynch MT. The intensification of gender-related role expectations during early adolescence. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Peterson A, editors. Girls at puberty. Plenum Publishers; New York: 1983. pp. 201–228. [Google Scholar]

- Hill JP, Holmbeck GN. Attachment and autonomy during adolescence. Annals of Child Development. 1986;3:145–189. [Google Scholar]

- Howard DE, Kaljee L, Rachuba LT, Cross SI. Coping with youth violence: Assessments by minority parents in public housing. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27:483–492. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.5.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis SF, Fremouw W. Dating violence: A critical review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21(1):105–127. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S, Sorenson SB, Aneshensel CS. Community and dating violence among adolescents: Perpetration and victimization. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1997;21:291–302. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElhaney KB, Allen JP. Autonomy and adolescent social functioning: The moderating effect of risk. Child Development. 2001;72:220–235. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElhaney K, Allen JP, Stephenson J, Hare AL. Attachment and autonomy during adolescence. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology, Vol 1: Individual bases of adolescent development. 3rd John Wiley & Sons Inc; Hoboken, NJ US: 2009. pp. 358–403. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1990;61:311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JG, Raj A, Mucci LA, Hathaway JE. Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286:572–579. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Mounts NS, Lamborn SD, Dornbusch SM. Authoritative parenting and adolescent adjustment across various ecological niches. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1991;1:19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2) development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of family issues. 1996;17(3):283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Tate DC. A longitudinal study of violent behavior in mid to late adolescence: Familial factors and the development of internal controls. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 1999;60(1-B):0393. [Google Scholar]

- Temple JR, Freeman DH., Jr. Dating violence and substance use among ethnically diverse adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26:701–718. doi: 10.1177/0886260510365858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagi KJ, Rothman E, Latzman NE, Tharp AT, Hall DM, Breiding M. Beyond correlates: A review of modifiable risk and protective factors for adolescent dating violence perpetration. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9907-7. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virginia Department of State Police, U. C. R. S. Author; Richmond, VA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker DJ, Murphy CM, Eckhardt CI, Hodges AE, Cowart M. A review of programs to prevent intimate partner violence: Findings from the Partner Abuse State of Knowledge Project. Partner Abuse. 2013;4:175–195. [Google Scholar]