Abstract

A neuroimaging technique based on the saturation-recovery (SR)-T1 MRI method was applied for simultaneously imaging blood oxygenation level dependence (BOLD) contrast and cerebral blood flow change (ΔCBF), which is determined by CBF-sensitive T1 relaxation rate change (ΔR1 CBF). This technique was validated by quantitatively examining the relationships among ΔR1 CBF, ΔCBF, BOLD and relative CBF change (rCBF), which was simultaneously measured by laser Doppler flowmetry under global ischemia and hypercapnia conditions, respectively, in the rat brain. It was found that during ischemia, BOLD decreased 23.1±2.8% in the cortical area; ΔR1 CBF decreased 0.020±0.004s-1 corresponding to a ΔCBF decrease of 1.07±0.24 ml/g/min and 89.5±1.8% CBF reduction (n=5), resulting in a baseline CBF value (=1.18 ml/g/min) consistent with the literature reports. The CBF change quantification based on temperature corrected ΔR1 CBF had a better accuracy than apparent R1 change (ΔR1 app); nevertheless, ΔR1 app without temperature correction still provides a good approximation for quantifying CBF change since perfusion dominates the evolution of the longitudinal relaxation rate (R1 app). In contrast to the excellent consistency between ΔCBF and rCBF measured during and after ischemia, the BOLD change during the post-ischemia period was temporally disassociated with ΔCBF, indicating distinct CBF and BOLD responses. Similar results were also observed for the hypercapnia study. The overall results demonstrate that the SR-T1 MRI method is effective for noninvasive and quantitative imaging of both ΔCBF and BOLD associated with physiological and/or pathological changes.

Introduction

Cerebral blood perfusion through the capillary bed is essential for brain function. Imaging of cerebral blood flow (CBF) provides valuable information regarding brain physiology, function, activation and tissue viability associated with a large number of brain diseases. Arterial spin labeling (ASL), a noninvasive MRI technique which utilizes the radiofrequency (RF) pulse to label the flowing arterial water spin as an endogenous and diffusible tracer for imaging CBF [1–7], plays an ever-growing role in scientific and clinical research. An inversion-recovery preparation is commonly applied for most ASL methods, and paired images (one control and another with spin tagging) are acquired with an appropriate inversion recovery time. The signal difference between the paired images can be used to determine the CBF value and it is particularly useful for imaging relative CBF changes, for instance, induced during brain activation [8, 9] and/or physiology/pathology perturbations.

An alternative MRI-based CBF imaging method is to measure the parametric parameter of apparent longitudinal relaxation time (T1 app) directly by using inversion-recovery preparation with varied inversion-recovery time (TIR) [2, 6, 10]. Due to the slow T1 app relaxation processing, this method requires a relatively long repetition time (TR) to acquire a serial of images with different TIR values in order to generate T1 app images, thus, results in low temporal resolution for imaging CBF. Nevertheless, this method should be robust in quantifying CBF and its change in the absolute scale with the unit of ml blood/g brain tissue/min (or ml/g/min) owing to a simple relationship between T1 app and CBF (see more details in Method and Theory).

One common, interesting observation related to T1 app changes reported in the literature is the detection of T1 app increase at an early stage of ischemia, indicating a possible link between the brain tissue T1 app change and the perfusion deficit caused by the ischemia [11–14]. However, the quantitative relationship between the observed T1 app change and the CBF reduction extent caused by acute ischemia has not been rigorously, quantitatively studied. A potential difficulty for quantifying CBF via the measurement of T1 app lies on the confounding effect from the brain tissue temperature change owing to physiological and/or pathological perturbation, which can also contribute to the T1 app change [15–18]. Consideration and correction of this confound effect might improve the accuracy of quantifying CBF based on the T1 app measurement. Another layer of complexity is the phenomena of concurrent changes in both perfusion and the blood oxygenation level dependence (BOLD) contrast [19, 20] during either physiology perturbation (e.g., brain stimulation) or pathology perturbation (e.g., hypoxia via ischemia); and these changes could affect the MRI intensity via either T1 app based mechanism owing to perfusion change or the transverse (or apparent transverse) relaxation time (T2/T2*) based mechanism owing to BOLD contrast.

To address these issues, we conducted a study aiming to: i) develop a robust neuroimaging approach to simultaneously measure and image the CBF change and the BOLD contrast by using the saturation-recovery (SR)-T1 MRI method; ii) validate this approach by conducting simultaneous in vivo measurements of CBF change using the SR-T1 MRI method and the relative CBF change using laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF) recording under transient hypercapnia (increasing CBF) and acute ischemia (reducing CBF) conditions using a rat model at 9.4T; iii) investigate the effect of brain temperature change on T1 app and the apparent longitudinal relaxation rate (R1 app = 1/T1 app) after the induction of hypercapnia or ischemia (see S1 Supporting Information); iv) establish the quantitative relationship between the CBF-sensitive R1 change (ΔR1 CBF) and the CBF change (ΔCBF); and v) quantitatively study the temporal relationships among R1 CBF change, ΔCBF, relative CBF change and BOLD during and after hypercapnia or ischemia.

Method and Theory

The SR-T1 MRI pulse sequence for imaging T1 app

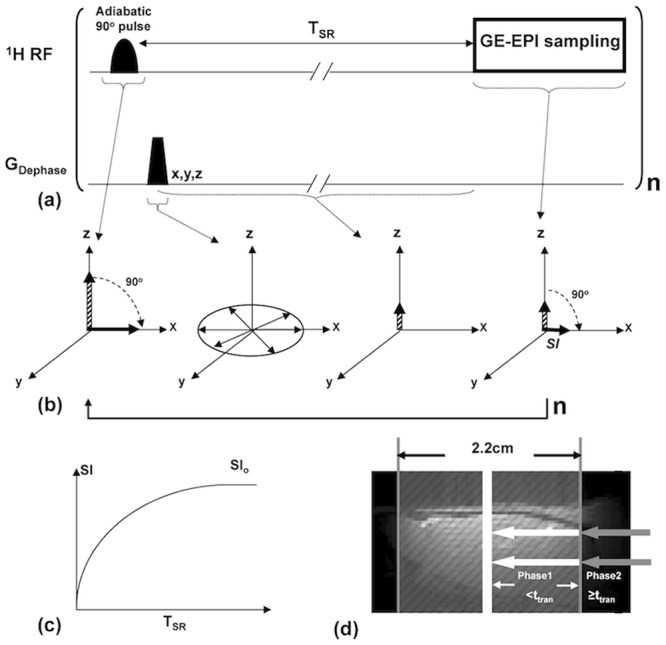

The MRI perfusion method described herein relies on quantitative T1 app mapping using the magnetization saturation-recovery preparation without slice selection and fast gradient-echo echo-planar imaging (GE-EPI) sampling [21]. The regional saturation-recovery preparation is confined by using a RF surface coil with a focal, intense RF field (B1) covering the rat brain [22]. Fig 1 is the schematic diagram showing the imaging pulse sequence and principle underlying the SR-T1 MRI method. The magnetization saturation preparation is achieved by an adiabatic half passage 90° RF pulse, which is insensitive to the inhomogeneous B1 field of a surface coil, immediately followed by dephasing gradients (GDephase) in three dimensions (Fig 1a). The adiabatic 90° pulse rotates the longitudinal magnetization (Mz) into the transverse plane in a spin-rotating frame, resulting in the transverse magnetization (Mxy) with the same magnitude of Mz. The Mxy rapidly loses its phase coherence because of the strong dephasing effect by GDephase. The overall effect of the magnetization saturation preparation in combination with the dephasing gradients is to approach zero magnetizations for both Mz and Mxy components (Fig 1b). This magnetization preparation is independent of the initial Mz value or its reduction from the previous scan owing to the partial magnetization saturation effect when a relatively short TR is applied. Therefore, no extra delay before the adiabatic 90° pulse is needed. This feature can significantly shorten the total image acquisition time and improve the temporal resolution for imaging T1 app as compared to the conventional inversion-recovery preparation in which the net magnitude of inverted Mz depends on the initial Mz prior to the inversion pulse and the effect of partial saturation as a function of TR, thus, a relatively long TR is preferred for each TIR measurement. During the period of saturation-recovery time (TSR), the longitudinal magnetization starts to relax and recover approximately according to an exponential function (Fig 1c). This recovered Mz after a period of TSR is rotated to the transverse plane again by a spin excitation RF pulse with a nominal 90° flip angle, and then sampled by EPI acquisition. The detected EPI signal intensity (SI) without considering the perfusion effect on T1 app obeys the following equation:

| (1) |

where TE is the spin echo time; and T2* is the apparent transverse relaxation time, which is sensitive to magnetic field inhomogeneity and susceptibility effect, such as the BOLD contrast; SI0 is the EPI signal intensity when TE = 0 and TSR = ∞. This equation can be used for T1 app regression based on a number of SI measurements with varied TSR. When TSR is sufficiently long (e.g., ≥5T1 app as applied in this study) and TE>0, the second term in (Eq 1) approaches one, and (Eq 1) becomes:

| (2) |

Under this condition, SI* is determined by the T2* relaxation process and becomes independent of T1 app; thus, this signal can be used to quantify the “true” BOLD contrast without confounding effect from the saturation effect caused by the perfusion contribution [19, 20, 23]. Moreover, the addition of SI* measurement with a long TSR, thus, a long TR is also critical to improve the reliability and accuracy for T1 app regression, which is essential in determining the absolute CBF change, though it leads to a relatively low temporal resolution for simultaneously obtaining T1 app and BOLD images.

Fig 1. Schematic diagram of the SR-T1 MRI sequence and spin magnetization evolution in rotating frame.

(a) Gradient-echo EPI (GE-EPI) sampling is applied after the saturation-recovery waiting time (TSR). There is no an extra delay time between the imaging acquisition and the next saturation pulse. This imaging measurement is repeated n times with varied TSR. (b) Schematic diagram illustrating the principle underlying the imaging sequence in the spin-rotating frame. It shows the rotation of longitudinal magnetization (Mz), dephasing of transverse magnetization (Mxy) and its evolution after TSR and spin excitation pulse followed by GE-EPI acquisition. (c) Exponential recovery curve of GE-EPI signal intensity (SI) as a function of TSR. The regression of this curve determines the apparent T1 (T1 app) value that is sensitive to perfusion. (d) Schematic diagram of two-phase model incorporated with the SR-T1 method developed in this study. The regional saturation zone (gray shaded area) achieved by a surface RF coil overlapped on a rat brain sagittal anatomic image. The white arrows stand for the Phase 1 arterial spins in the saturated region traveling into the image slice within the time window ttran (i.e., when TSR<ttran) The gray arrows indicate the unsaturated Phase 2 arterial blood spins flowing into the image slice when the traveling time is longer than ttran or equal to (i.e., when TSR ≥ ttran).

In this study, two brain conditions are defined by the subscript “RC” standing for the Reference Condition (i.e., control) before the induction of physiological/pathological perturbation, and the subscript “PC” standing for the Perturbed Condition by the induction of either hypercapnia (hyper-perfusion) or ischemia (hypo-perfusion). Accordingly, the BOLD contrast can be quantified by:

| (3) |

where rBOLD stands for the relative BOLD.

Two-phase arterial spin modeling of the SR-T1 MRI method

The Block equation describes the dynamic behavior of brain water magnetization as the following:

| (4) |

where Ma, Mb and Mv are the longitudinal water magnetization of the arterial blood, brain tissue and venous blood respectively; Mb 0 is the equilibrium value of Mb; T1 is the brain tissue water longitudinal relaxation time in the absence of blood flow; f represents the CBF value. Associated with the proposed experimental MR preparation and acquisition, we solve (Eq 4) with a two-phase arterial spin model as illustrated in Fig 1d, showing the schematic graph of the global brain region (shaded gray area) saturated by the RF coil overlapped on a rat brain sagittal anatomic image. Phase 1 represents the time window in which the image slice receives the flowing saturated arterial spins within the regional saturation region (as indicated with the white arrows in the Fig 1d); and Phase 2 characterizes the time window when the fresh, fully relaxed arterial spins sitting outside of the saturation region (as indicated with the gray arrows in Fig 1d) flowing into the image slice. Assuming the arterial blood spins travel smoothly as bulk flow at a constant speed without any turbulence, the fresh spins at the edge of the saturation region will take the artery transit time (ttran) to reach the image slice. For the SR-T1 measurement with the boundary condition of Mb(t = 0) = 0, the final solution (see S1 Supporting Information for details) for (Eq 4) and Phase 1 when t< ttran follows:

| (5) |

where T1a is the longitudinal relaxation time of arterial blood and

| (6) |

where λ (= 0.9 ml/g) is the brain-blood partition coefficient, T1 temp (R1 temp) is the contribution of temperature-dependent longitudinal relaxation time (rate) caused by brain temperature alteration during physiological or pathological perturbation (see S1 Supporting Information).

During Phase 2 the fully relaxed artery spins in the blood outside the saturation region flow into the rat brain, and will approach the image plane and exchange with the brain tissue water spins when t≥ttran. Final solution for Phase 2 of (Eq 4) when t≥ttran with the initial condition using (Eq 5) with the boundary condition of t = ttran gives:

| (7) |

where CA and CB are the constants which equal to A and B in (Eq 5), respectively, when t = ttran, they reflect the boundary condition and ensure the function continuity between Phase 1 and Phase 2. Therefore, when the saturation recovery time is shorter than ttran (Phase 1), the magnetization of brain tissue water relaxes following (Eq 5) whereas when the saturation recovery time is longer than or equal to ttran it will relax according to (Eq 7) instead. It is clear that the brain magnetization recovery with a long saturation recovery time of TSR≥ttran (Phase 2) follows a single exponential relaxation time T1 app (Eq (7)), while the magnetization recovery in Phase 1 (TSR<ttran) in theory is influenced by both T1 app and T1a (see (Eq 5)).

Close examination of (Eq 5) for Phase 1, one can see that the signal recovery described by the term A only depends on T1 app whereas the signal recovery of the term B relies on both T1 app and T1a. A simulation study was conducted using (Eq 5) and the parameters relevant to this study for comparing the relative contributions of A and B terms (see S1 Supporting Information) and it turns out that the term B in (Eq 5) is less than 4% of the term A within a reasonable artery transit time range (100–500ms) in the rat brain [1, 24–26]. Therefore, a single exponential recovery according to the term A is a rational approximation for the rat brain application during Phase 1 (TSR<ttran) since the magnetization contribution from the term B is negligible. Therefore, the exponential recovery functions for both Phase 1 and Phase 2 can be unified as a single exponential recovery function according to T1 app. In summary, a single exponential fitting of T1 app based on multiple SR-T1 MRI measurements with varied TSR values presents a simple approach and good approximation for imaging T1 app or R1 app which can be quantitatively linked to CBF according to (Eq 6).

Imaging T1 app (or R1 app), T1 CBF (or R1 CBF) and CBF change (ΔCBF)

The T1 and R1 term in (Eq 6) represent the intrinsic brain tissue property of longitudinal relaxation time and rate, respectively; they are usually insensitive to physiological changes and can be treated as constants. The R1 app difference between the reference and perturbed conditions becomes:

| (8) |

where ΔCBF = CBFPC—CBFRC. Thus, CBF change (ΔCBF) between perturbation and reference conditions can be calculated from the following equation:

| (9) |

where ΔR1 CBF presents the R1 change, which is solely attributed to the CBF change induced by physiopathological perturbation; and it can be imaged by the SR-T1 MRI method through three steps: i) image brain MRI SI as a function of TSR during both control and perturbed conditions, and then determine the T1 app values in each image pixel by the exponential regression of measured SI as a function of TSR according to (Eq 1); ii) subtract the control R1 app (= 1/T1 app) value from the perturbed R1 app value resulting in ΔR1 app; iii) determine ΔT1 temp or ΔR1 temp caused by a brain temperature change induced by perturbation (see S1 Supporting Information), then calculate ΔR1 CBF and ΔCBF according to (Eq 9). The unit of CBF in (Eq 9) is ml/g/second, which can be converted to a conventional unit of ml/g/min by multiplying CBF by 60.

Materials and MRI Measurements

Animal preparation and Experiment Design

All animal experiments were conducted according to the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and under the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of University of Minnesota. Twelve male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 328 ± 35 g were included in this study. The rat was initially anesthetized and intubated using 5% (v/v) isoflurane in N2O:O2 (60/40) gas mixture. Both femoral arteries and left femoral vein were catheterized for physiological monitoring and blood sampling. Five rats were used for simultaneous MRI/LDF/temperature measurements. The LDF/Temperature instrument (Oxford Optronix, UK) was used to concurrently measure the percentage change of CBF or the relative CBF change that is defined as rCBF = CBFPC/CBFRC and the brain temperature change in the cortical region in one hemisphere by inserting the LDF/Temperature probe (0.5 mm diameter) into the brain tissue through a small hole (3×3 mm2) passing both skull and dura (1.5–4 mm lateral, 1.5–3 mm posterior to the bregma, 1.9 mm deep). The soft tissue around the hole was kept to minimize magnetic susceptibility artifacts in MRI. After the surgical operation, the rat was placed in a home-built cradle incorporating ear bars and a bite bar to reduce head movement and to ensure proper positioning inside the MRI scanner. The animal anesthesia was maintained at 2% isoflurane. Rectal temperature was maintained at 37.0±0.5°C by a circulating/heating water blanket and the rate and volume of ventilation were adjusted to maintain normal blood gases.

Mild transient hypercapnia was induced in eight of the twelve rats used in this study by ventilating the gas mixture of 10% CO2, 2% isoflurane and 88% N2O:O2 (60/40) for 7 minutes; three of the eight rats were used for simultaneous measurements of ΔR1 CBF, ΔCBF and BOLD using the SR-T1 MRI method, and rCBF and temperature (T) change using the LDF/Temperature probe; and other five rats were used to conduct the MRI experiments only.

All twelve rats performed 1-minute occlusion of the two carotid arteries to achieve acute, global brain ischemia using the four-blood-vessel-occlusion rat model [27]. The transient hypercapnia experiment was performed first, followed by the acute ischemia experiment, and the rats were sacrificed by KCl injection for approaching cardiac arrest at the end of the experiment. There was an adequately long waiting time between these studies to ensure stable animal conditions prior to each perturbation and measurement. The SR-T1 GE-EPI data were acquired for two minutes prior to each perturbation of transient hypercapnia (7 minutes), acute ischemia (1 minute) or KCl injection for approaching cardiac arrest. This control (or prior-perturbation) imaging acquisition period is defined as Stage 1. The duration during either the transient hypercapnia or acute ischemia perturbation is defined as the perturbation stage or Stage 2. Finally, the relatively long post-perturbation period was divided into three stages (i.e., early Stage 3; middle Stage 4 and late Stage 5).

MRI measurement

All MRI experiments were conducted on a 9.4T horizontal animal magnet (Magnex Scientific, Abingdon, UK) interfaced to a Varian INOVA console (Varian, Palo Alto, CA, USA). A butterfly-shape 1H surface coil (2.8×2.0 cm with the short axis paralleled to the animal spine) was used to collect all MRI data. Scout images were acquired using a turbo fast low angle shot (TurboFLASH) imaging sequence [28] with the following acquisition parameters: TR = 10 ms, TE = 4 ms, image slice thickness = 2 mm, field of view (FOV) = 3.2 cm×3.2 cm; image matrix size = 128×128.

The magnetization saturation of water spin inside the rat brain was achieved by using the local B1 field of the RF surface coil and the adiabatic 90°RF pulse followed by three orthogonal dephasing gradients. GE-EPI (TE = 21 ms; FOV = 3.2cm×3.2cm; image matrix size = 64×64; single slice coronal image with 2 mm thickness) combined with the saturation-recovery preparation was used to image T1 app with seven TSR values of 0.004, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5 and 10 s, which resulted in a temporal resolution of 11.9 s for obtaining one set of T1 app and BOLD images. This SR-T1 GE-EPI imaging sequence (see Fig 1a) was applied to: i) measure ΔR1 CBF resulting from either hypercapnia (CBF increase) or acute ischemia (CBF reduction) compared to the control condition; ii) determine the relationship between brain temperature change and ΔR1 temp immediately after the cardiac arrest (i.e., CBF = 0) with a KCl bolus injection (see S1 Supporting Information for details); and iii) determine ΔCBF values and then compare and correlate the values with the LDF measurement results.

Data analysis

MRI data analysis was performed using the STIMULATE software package (Stimulate, Center for Magnetic Resonance Research, University of Minnesota, USA) [29] and the Matlab software package (The Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). LDF data was sub-sampled to match the corresponding MRI sampling rate and processed with home-written Matlab programs. Both region of interest (ROI) and single pixel MRI data taken from the rat sensory cortical region were used to perform the T1 app regression analysis and to determine ΔR1 app, ΔR1 temp (see S1 Supporting Information for details) and ΔCBF according to Eqs (8) and (9). The least-square nonlinear curve-fitting program using the Matlab software was applied to perform the T1 app regression analysis. The regression accuracy was estimated by the sum squared error (sse) and the square of regression coefficient (R2).

To improve the quantification accuracy, the GE-EPI data were averaged within each stage as defined above and then applied to calculate the averaged values of ΔR1 app, ΔR1 temp and ΔCBF based on the transient hypercapnia or acute ischemia measurement. The reference control CBF (CBFRC) was further estimated from the averaged ΔCBF values and its corresponding relative CBF changes (rCBF) measured by LDF under ischemia condition and during the reperfusion period after the acute ischemia. ROIs (ranging from 24 to 52 pixels) were chosen from the cortical brain region in the intact hemisphere with the location being approximately contralateral to the LDF recording side for those experiments performing simultaneous MRI and LDF/Temperature measurements in order to avoid the MRI susceptibility artifacts caused by the LDF/Temperature probe. The GE-EPI data acquired with the longest TSR of 10 s (i.e., ≈ 5T1) were used to calculate BOLD according to (Eq 3).

The R1 app images at the control stage and a series of ΔCBF and BOLD images measured during and post hypercapnia and/or ischemia stages were created on a pixel-by-pixel basis (pixel size 0.25×0.25×2 mm3, with nearest neighbor interpolation) with two-dimensional median filtering and then overlapped on the anatomic image. Paired t-test was applied to compare the T1 app values measured at reference and perturbation conditions obtained from either ROIs or single pixel, as well as to compare the regressed T1 app values using ROI or single pixel data under a given condition. A p value of < 0.05 is considered as statistically significant.

Results

Reliability and sensitivity of T1 app measurement using the SR-T1 MRI method

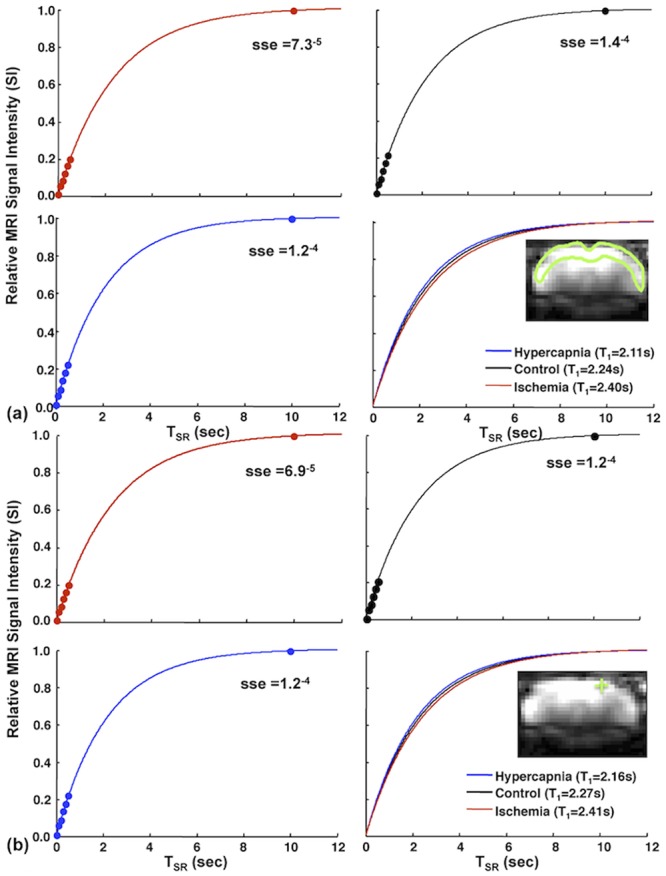

The averaged T1 app value measured using the SR-T1 MRI method in the rat cortex region under the normal physiological condition was 2.30±0.03 s (n = 12) at 9.4T. Fig 2 demonstrates a representative, single SR-T1 GE-EPI measurement under control, hypercapnia and ischemia condition, respectively, and the T1 app regression results based on ROI (Fig 2a) and single pixel (Fig 2b) data analysis without signal averaging. All the experimental data fitted well with an exponential function (R2≥0.99 and sse <2×10-4). The T1 app regression curves and the fitted T1 app values measured under control, hypercapnia and ischemia conditions were distinguishable and highly reproducible; and the results between the ROI and single pixel data analysis were consistent (Fig 2). For instance, no statistical difference was found between the T1 app values obtained from the ROI analysis versus single pixel analysis under either the hypercapnia (p = 0.93, 12 image volumes using paired t-test) or the ischemia (p = 0.83, 5 image volumes using paired t-test) condition. These results reveal a high reliability of the proposed MRI method for imaging T1 app and its change down to the pixel level, and this reproducibility is crucial in generating reliable T1 app maps. Moreover, the determined T1 app values under the hypercapnia and ischemia perturbations were statistically different from the control T1 app value (p<0.01), indicating that the T1 app relaxation process is sensitive to the perfusion changes induced by physiology/pathology perturbations. It is worth to note that adding more TSR points in a median TSR range (e.g., few seconds) could be helpful to further improve the fitting accuracy of T1 app (or R1 app) measurement with a tradeoff of reduced imaging temporal resolution; nevertheless, the benefit on the outcome of ΔR1 app, thus, ΔCBF measurement is insignificant because of the cancelation of the systematic errors of R1 app measurements under control and perturbation conditions (data not shown herein). One could optimize the TSR values and the number of TSR points for achieving a proper balance between the T1 app fitting accuracy and imaging temporal resolution.

Fig 2. T1 app regression time courses with the SR-T1 MRI method.

Time courses from a single SR-T1 GE-EPI measurement and T1 app regression under control (black lines); hypercapnia (blue lines); and ischemia (red lines) conditions based on (a) ROI and (b) single EPI pixel located inside the rat brain cortex. Colored dots are the signal data points imaged at different TSRs under different conditions. Three T1 fitting lines and their T1 app values under three conditions are also displayed in (a) and (b). The inserts show a coronal brain GE-EPI from a representative rat, indicating the location of (a) the ROI (enclosed in the green solid line) and (b) a single pixel (green cross mark) used for the regression (sse stands for the sum squared error; R2 = 0.99).

Relationships between rCBF, relative R1 CBF and BOLD induced by perturbations

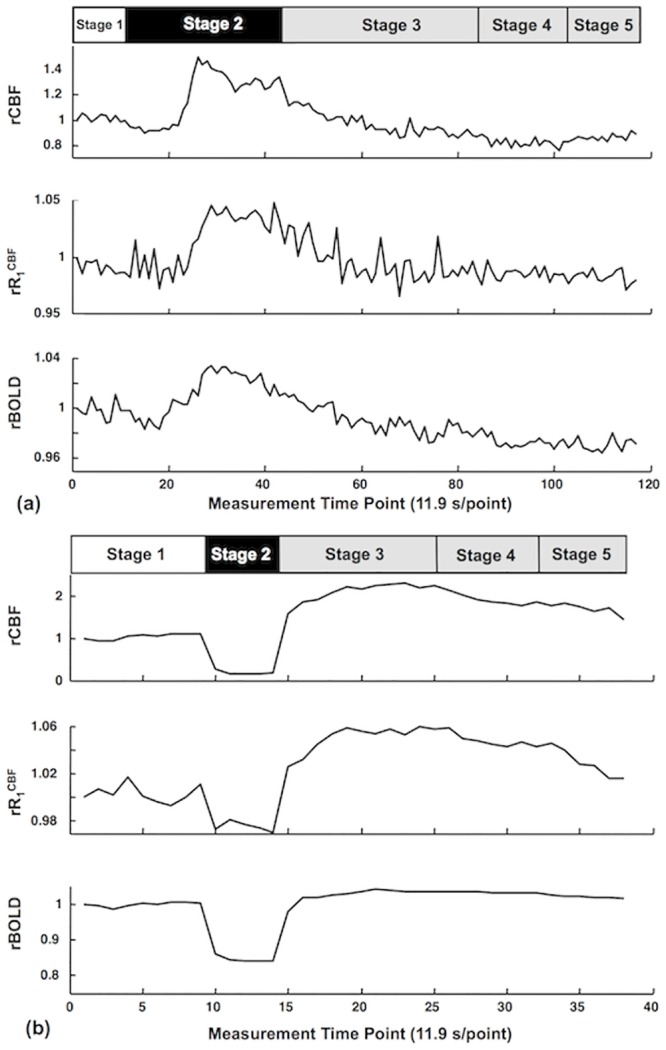

Fig 3 shows the high temporal resolution (~12 s per data point) time courses of relative R1 CBF (rR1 CBF: the R1 CBF ratio between RC and PC conditions) and rBOLD measured by the SR-T1 MRI method from the ROI located in the rat sensory cortex and rCBF measured by LDF in the similar brain region before, during and after (a) transient hypercapnia and (b) acute ischemia perturbation from a representative rat. Despite some fluctuations, these time courses display expected temporal behaviors and dynamics. First, there are approximately parallel trends among all of the measured time courses. Secondly, the transient hypercapnia led to significant increases in the measured parameters owing to the vascular dilation effect, thus, increasing perfusion followed by a recovery back to the baseline level after the termination of hypercapnia. Thirdly, the acute ischemia caused rapid reductions in all measured parameters followed by a substantial overshooting (reperfusion) after the termination of ischemia and a slow recovery to the baseline level. Nevertheless, a careful examination of Fig 3 suggests a stronger temporal correlation between the measured rR1 CBF and rCBF (correlation coefficient = 0.84 for hypercapnia and 0.90 for ischemia, p<0.01) compared to the correlation of rR1 CBF versus rBOLD (correlation coefficient = 0.78 for hypercapnia and 0.75 for ischemia, p<0.01). Relative BOLD (rBOLD) shows a more significant undershoot after the hypercapnia (Fig 3a) and a smaller overshooting after the ischemia than that of rR1 CBF and rCBF (Fig 3b). These results reveal the feasibility of the SR-T1 MRI method to simultaneously measure BOLD and rR1 CBF which is tightly correlated to the CBF change; and its ability to temporally dissociate the BOLD and CBF responses with relatively high temporal resolution. It is also interesting to note that the rR1 CBF time course had a relatively large fluctuation compared to the BOLD time course, presumably owing to a moderately low inherent contrast-to-noise ratio to measure the CBF change.

Fig 3. Time courses of relative rR1 CBF, rBOLD and rCBF of hypercapnia and global ischemia experiments.

Time courses of relative R1 CBF (rR1 CBF) and relative BOLD (rBOLD) measured by the SR-T1 MRI method, relative CBF change (rCBF) measured by LDF before, during and after (a) hypercapnia and (b) ischemia perturbation from a representative rat (data extracted from a region of interest). The bar graphs on top indicate the experimental acquisition protocol of (a) hypercapnia and (b) ischemia. Five stages are defined for imaging acquisition under varied animal conditions. Stage 1 represents the control (or prior-perturbation) period (2 minutes) prior to the induction of perturbations (i.e., hypercapnia or ischemia). Stage 2 represents the perturbation period either for the transient hypercapnia (7 minutes) or acute ischemia (1 minute). Stages 3, 4 and 5 represent the three post-perturbation periods with varied time duration after either the transient hypercapnia or acute ischemia perturbation. Because the post-perturbation effects on CBF and BOLD responses were much shorter for the 1-minute acute ischemia perturbation than that of 7-minute transient hypercapnia perturbation, the durations for these three stages were different for these two perturbation studies: i) for the hypercapnia perturbation: 8 minutes for Stage 3; 3.4 minutes for Stage 4 and 3.2 minutes for Stage 5; and ii) for the ischemia: 2.4 minutes for Stage 3; 1.4 minutes for Stage 4 and 1.2 minutes for Stage 3. Please note that there were noticeable dynamic response delays (about 2 minutes) of CBF and BOLD response owing to a large dead volume in the ventilation system when slowly increasing the inhaled CO2 concentration during the hypercapnia experiment.

During the ischemia perturbation, R1 CBF decreased 4.7±1.2% (n = 5) compared to the control condition, which was equivalent to a 5.1±1.4% increase of ΔT1 CBF; accordingly, CBF decreased 89.5±1.8% and BOLD decreased 23.1±2.8%. During the hypercapnia, in contrast, R1 CBF increased 5.1±0.8% (n = 3); ΔT1 CBF decreased 4.8 ± 0.7%; CBF increased 82±12%; and BOLD increased 4.5±2.7%.

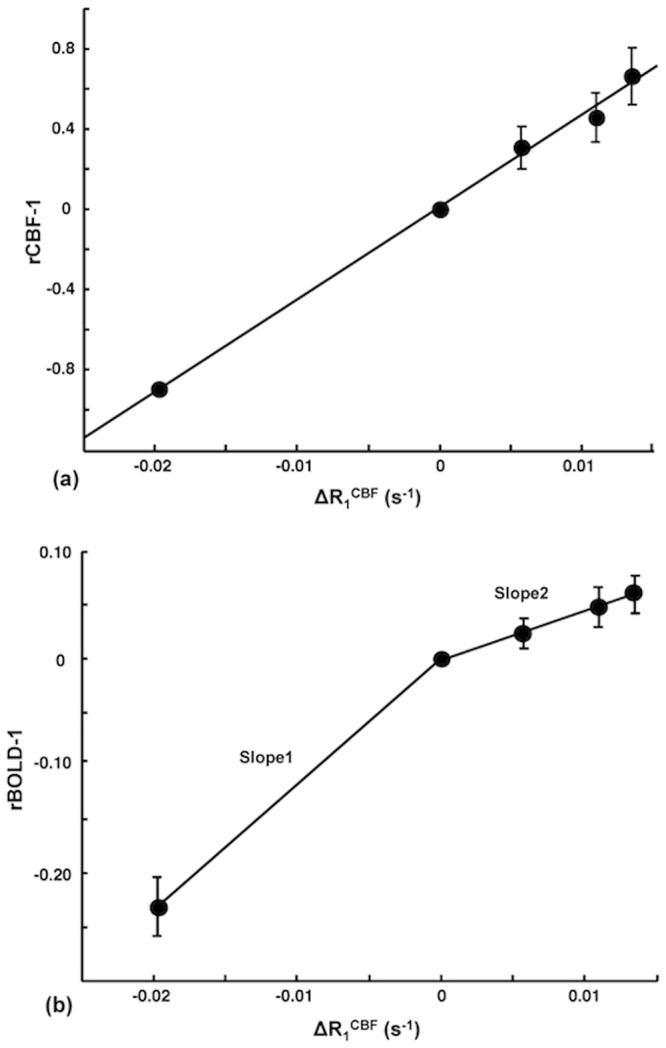

Fig 4 shows the plots of ΔR1 CBF versus (rCBF-1) (Fig 4a) and versus (rBOLD-1) (Fig 4b) measured for the ischemia study. It indicates an excellent consistency and strong linear correlation between the CBF change and ΔR1 CBF across all five stages studied; and the correlation can be described by the following numerical equation that was obtained by the linear regression:

| (10) |

with R2 = 0.99. In contrast, two distinct linear fitting slopes (slope ratio = 2.6) were observed between ΔR1 CBF and (rBOLD-1), indicating the independence of the SR-T1 MRI method for simultaneously determining ΔR1 CBF and BOLD; and showing the decoupled changes of these two physiological parameters during the post-ischemia stages.

Fig 4. Correlation between ΔR1 CBF versus (a) rCBF-1 and (b) rBOLD-1.

Correlation between the averaged ΔR1 CBF measured by the SR-T1 MRI method versus (a) rCBF-1 and (b) rBOLD-1 obtained during the five stages of ischemia experiment. The vertical bars indicate the standard error (SEM) (n = 5). There is a strong, positive correlation between (rCBF-1) and ΔR1 CBF in (a). In contrast, there are two distinct linear fitting slopes between (rBOLD-1) and ΔR1 CBF in (b) owing to the decoupled change between them during the post-ischemia stages.

Table 1 summarizes the results of simultaneous rCBF (by LDF) and ΔR1 CBF measurements (by the SR-T1 MRI method) during the ischemia (Stage 2) and the first post-ischemia period (Stage 3) for each rat and averages among inter-subjects. The ΔR1 CBF value was used to calculate the CBF change (ΔCBF) according to (Eq 9), and then rCBF and ΔCBF were applied to estimate the reference control (or baseline condition) CBF (i.e., CBFRC) according to the following relationship:

| (11) |

Table 1. Summary of ΔR1 CBF, ΔCBF, (rCBF-1) and the estimated reference control CBF.

| Ischemia Stage (Stage 2) | Ischemia Overshooting Stage (Stage 3) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat No. | ΔR1 CBF(s-1) | Calculated ΔCBF (ml/g/min) | rCBF-1 | Control CBF (ml/g/min) | ΔR1 CBF(s-1) | Calculated ΔCBF (ml/g/min) | rCBF-1 | Control CBF (ml/g/min) |

| 1 | -0.023 | -1.247 | -0.883 | 1.413 | 0.014 | 0.751 | 0.332 | 2.263 |

| 2 | -0.036 | -1.928 | -0.899 | 2.145 | 0.024 | 1.280 | 1.104 | 1.159 |

| 3 | -0.014 | -0.778 | -0.924 | 0.841 | 0.016 | 0.880 | 0.597 | 1.474 |

| 4 | -0.012 | -0.664 | -0.833 | 0.798 | 0.006 | 0.346 | 0.834 | 0.415 |

| 5 | -0.013 | -0.713 | -0.938 | 0.760 | 0.007 | 0.389 | 0.445 | 0.874 |

| Mean ±SEM | -0.020±0.005 | -1.066±0.239 | -0.895±0.018 | 1.191±0.267 | 0.013±0.003 | 0.729±0.172 | 0.662±0.139 | 1.237±0.310 |

Summary of ΔR1 CBF, calculated CBF change (ΔCBF) based on ΔR1 CBF, (rCBF-1) measured with LDF during the ischemia (Stage 2) and the first post-ischemia stage (Stage 3); and the estimated reference control CBF of five individual rats and its mean and standard error values.

The estimated CBFRC was 1.19±0.27 ml/g/min calculated from the ischemia stage (Stage 2) data, and 1.24±0.31 ml/g/min calculated from the first post-ischemia stage (Stage 3) data, showing an excellent consistency between them. The estimated baseline CBF values in this study are coincident with the reported values in the literature ranging from 0.9 to 1.5 ml/g/min (1.29±0.05 ml/g/min) measured in the rat cortex under similar isoflurane anesthesia condition, which are summarized in S1 Supporting Information. Furthermore, if we approximate the small interception value of 0.01 to zero in (Eq 10) and replace (rCBF-1) term in (Eq 11) with the approximated (Eq 10), we derived CBFRC = (60sec/min)·λ(ml/g)/45.9(sec) = 1.18 ml/g/min using the relationship of (Eq 9). This value based on the regressed slope of 45.9 sec in (Eq 10) using the data shown in Fig 4a is again in good agreement with the averaged literature value of 1.29±0.05 ml/g/min. These comparison results provide ample evidence supporting the feasibility and reliability of the proposed SR-T1 MRI method in measuring and quantifying the CBF changes induced by physiological/pathological perturbations.

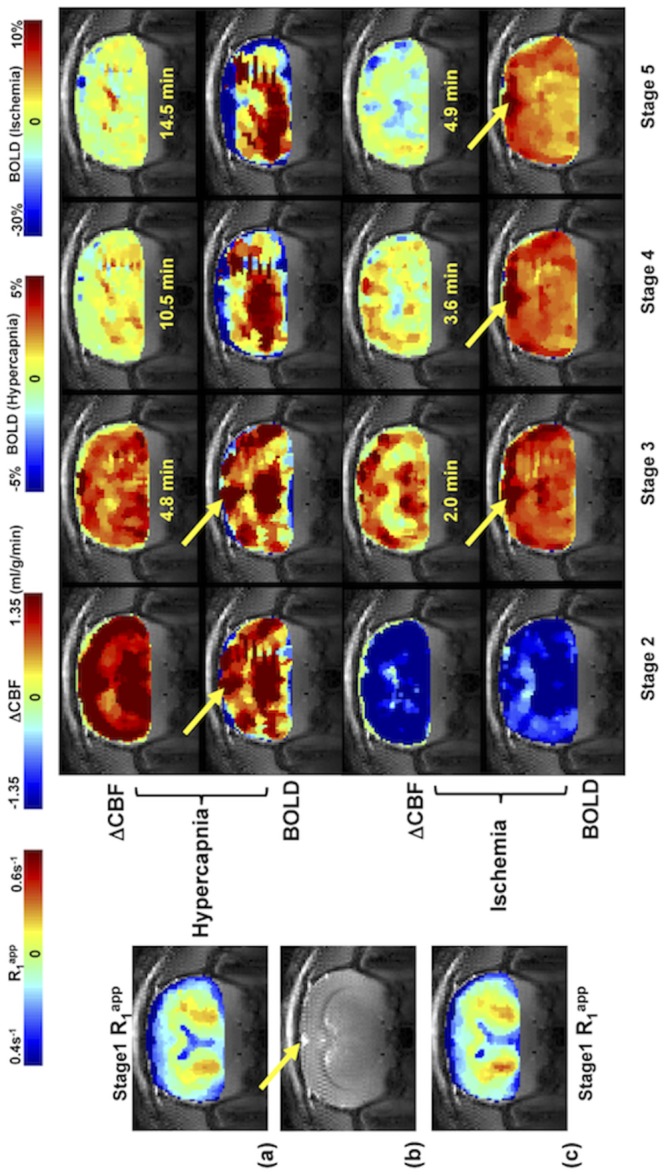

Fig 5 shows the control R1 app images (coronal orientation) of rat brain, anatomic image, and the ΔCBF and BOLD images measured by the SR-T1 MRI method during and after the hypercapnia/ischemia perturbation in a representative rat without the use of LDF probe to avoid the susceptibility MRI artifacts. It illustrates that the SR-T1 MRI method is robust and sensitive for noninvasively imaging the CBF changes in response to a physiological (hypercapnia) or pathological (ischemia) challenge with a few minutes of image acquisition time. Moreover, the BOLD images can also be simultaneously obtained.

Fig 5. Coronal anatomic image, R1 app images, ΔCBF and BOLD images of a representative rat.

(a) and (c) Reference control R1 app images (acquired during Stage 1); the SR-T1 MRI method generated ΔCBF and BOLD images of Stage 2 to Stage 5 obtained from (a) hypercapnia and (c) ischemia study, respectively from a representative rat brain. (b) Anatomic coronal image from the same rat. The time indicated between the ΔCBF and BOLD images is the approximate image sampling time after the termination of Stage 2. The yellow arrows point to the sinus vessel. The total image averaging time for Stages 2 to 5 were: 2.5, 6.5, 4.6 and 3.2 minutes for the hypercapnia study; and 1.0, 1.8, 1.4 and 1.2 minutes for the ischemia study.

Discussion

Underlying mechanism for imaging CBF change in rat brain using the SR-T1 imaging method

Instead of focusing on the magnetization change by delivering tagged spins to the image slice(s) at a certain TIR in the ASL approach, T1 perfusion model [2, 5, 6, 10] views CBF circulation as an enhanced longitudinal relaxation through T1 app as defined in (Eq 6). The rapid exchange between the saturated water protons in the image slice and the fully relaxed arterial blood water outside of the saturation region during the SR-T1 MRI measurement enables a quantitative link between T1 app and CBF. Based on the current MRI acquisition scheme used in this study, (Eq 5) (valid for Phase 1, when TSR < ttran) and (Eq 7) (valid for Phase 2 when TSR ≥ ttran) quantitatively describe the magnetization change as a function of TSR for the SR-T1 MRI method with a two-phase perfusion model shown in Fig 1d. According to (Eq 5), the brain tissue relaxation depends on both T1 app and T1a when TSR < ttran (Phase 1), however, the term B in (Eq 5) which contains T1a accounts for only few percentages of the term A and its contribution to the magnetization relaxation becomes insignificant. Therefore, a single exponential recovery function according to the T1 app relaxation time provides a good approximation. When TSR ≥ ttran (Phase 2), the brain tissue magnetization relaxation solely follows T1 app according to (Eq 7). Therefore, T1 app dominates the magnetization change through the entire TSR covering both Phase 1 and Phase 2, and can be robustly regressed for determining CBF changes. The excellent T1 app fitting curve (and excellent linearity in semi-log fitting, data not shown herein), as well as the high reproducibility and sensitivity to CBF alteration as shown in Fig 2 demonstrate that the single exponential function regression worked well in this study.

LDF measures a frequency shift in light reflected from moving red blood cells [30, 31]. It enables a real-time, continuous recording of relative (or percentage) CBF change in a focal region inside the brain; and is regarded as a standard tool for dynamic CBF measurements [32]. Moreover, LDF-based CBF measurements have been reported to be in good agreement with the radioactive microsphere CBF techniques [31, 33] as well as the hydrogen clearance CBF methods [34]. The excellent correlation between ΔR1 CBF measured with the SR-T1 method and relative CBF change recorded by LDF technique (Figs 3 and 4) during physiological/pathological perturbations, and the coincidence between the calculated baseline CBF results and the reported CBF values in the literature clearly suggest that ΔR1 CBF imaged by the SR-T1 MRI method quantitatively reflects the CBF changes. Besides the contributions from intrinsic T1 and CBF, T1 app can be also slightly influenced by other factors, for example, temperature. Although the temperature correction of T1 app could improve the accuracy of measurement, T1 app without the correction still provide a good approximation to calculate CBF change since the temperature induced T1 change is small (see S1 Supporting Information).

Advantages, limitations and methodology aspects of the SR-T1 method for imaging CBF change and BOLD

The SR-T1 MRI method has several unique merits when comparing it with the conventional ASL techniques using an inversion-recovery preparation. First, the modeling used to quantitatively link T1 app and CBF in the SR-T1 MRI method is simple and it requires much less physiological parameters aiming to quantify absolute ΔCBF according to (Eq 9). Second, the SR-T1 MRI method relies on parametric T1 app mapping; thus, it does not require the paired control image as applied in most ASL methods for determining CBF change. Third, the saturation-recovery preparation avoids the requirement of relatively long TR constrained by the conventional T1 imaging methods based on the inversion-recovery preparation; this enables relatively rapid mapping of T1 app and ΔR1 app to generate the ΔCBF image as illustrated in Fig 5. Although the imaging of T1 app requires multiple measurements with varied TSR values, its temporal resolution of 12 s per complete image set is comparable with other ASL methods (approximately 5–10 s). Fourth, the partial volume effect of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to ΔCBF is minimal because of the subtraction out the undisturbed CSF-related R1 contribution under various animal conditions, slow movement of CSF water spins (about 20 times slower than CBF, [35–37]) and the negligible exchange between CSF and brain tissue water spins.

This study was based on single slice measurement to prove the concept and feasibility of the proposed SR-T1 MRI method, nevertheless, it should be readily extended to multiple image slices covering a larger brain volume.

One technical limitation of the current SR-T1 MRI method is its inability to directly measure the baseline CBF value under a physiological condition of interest, thus, the control value of CBFRC was indirectly estimated by two independent measurements of ΔCBF and rCBF using the SR-T1 MRI method and LDF, respectively, in this study. This technique is more useable for imaging CBF changes, thus, requiring two measurement conditions, for instance, reference control versus perturbation (similar to the BOLD measurement) as presented in this study.

A surface RF coil generates an inhomogeneous distribution of B1 in space, resulting in a non-uniform RF pulse flip angle for saturating the water magnetization if a linear RF pulse waveform is used. In this study, we applied an adiabatic half passage 90° RF pulse to achieve relatively uniform 90° rotation of Mz into the transverse plane and to improve saturation efficiency, in particular, in the brain cortical region where B1 is strong. The ROI for data processing was chosen from this region (see Fig 2 for an example). In the deep brain region, distant from the surface coil, it might not be warranted to approach an adiabatic 90° rotation if the RF power is inadequate in this brain region. As a result, the RF saturation efficiency (0≤α≤1) can drop in the deep brain region and lead to relatively low saturation efficiency. However, this imperfection, if it exists, should not cause a significant error in determining T1 app owing to the following two reasons.

First, the term of α was considered in the least square regression to calculate the T1 app value using the following formula

| (12) |

in which three constants, k, α and T1 app are determined by regression. Though α can become less than 1 in the deep brain region if B1 strength is inadequately strong, it can be treated as a constant. The T1 app regression becomes insensitive to the absolute value of α; and the regression outcome is mainly determined by the exponential rate of SI recovery as a function of TSR.

Second, a nominal 90° excitation pulse and a very short TE were used in the GE-EPI sampling in this study. In addition, there was no extra delay between the EPI signal acquisition and the next RF saturation pulse. This configuration further reduces the residual Mz component (or suppresses the Mz recovery) before the next magnetization saturation preparation. It acts as extra magnetization saturation, resulting in an improved saturation efficiency and insensitivity of regression to the value of α. These notions are supported by the ΔCBF images (Fig 5a and 5c) showing relatively uniform CBF changes across the entire image slice including the deep brain region. In contrast, the BOLD images show the ‘hot’ spots around the sinus vein as pointed by the arrows in Fig 5 because of the large BOLD effect near a large sinus vein [19]. Such ‘hot’ spots were not observed in the ΔCBF images, indicating again that the ΔCBF image is more specific to the tissue perfusion and less susceptible to macro vessels. This differentiation between the simultaneously measured BOLD and ΔCBF images suggests that the SR-T1 MRI method indeed is able to independently but simultaneously measure two important physiological parameters: CBF change and BOLD. Although, there is a similar trend between the measured changes of ΔCBF and BOLD during ischemia or hypercapnia perturbation as shown in this study, there are clearly distinct characters in both spatial distribution and temporal behavior between the ΔCBF and BOLD images during the recovery periods after the perturbations, which provide complementary information of the brain hemodynamic changes in response to physiological/pathological perturbations.

The SR-T1 MRI method is based on the exponential fitting of R1 app using multiple EPI images with varied saturation-recovery times, and the R1 app changes caused by either hypercapnia or ischemia were small (<5%). Therefore, the accuracy of fitting is susceptible to the EPI image noise level, in particular, in the brain regions with EPI susceptibility artifacts or weak B1 of the surface coil.

Relationship between ΔR1 CBF and the CBF change during ischemia and hypercapnia

It is known that the development of vasogenic edema usually occurs at a later phase, approximately 30 minutes after the induction of regional ischemia [38]; and the water accumulation in the ischemic tissue owing to cellular swelling takes place hours after the onset of ischemia [39, 40]. It is unlikely that vasogenic edema and water content change could be responsible for the measured ΔR1 CBF change in the present study since the global ischemia lasted only one minute and the SR-T1 MRI measurements were continued within a relative short period during the post-perturbation stages. Therefore, ΔR1 CBF imaged by the SR-T1 MRI method could be fully quantified to determine and image ΔCBF. This notion is evident from the results of the ischemia study; and it also holds true for the hypercapnia study. However, it would be interesting to investigate the longitudinal T1 app change in the severely or chronically ischemic brain region, which could be affected by the CBF change and possibly other physiopathological changes (infarction, edema, necrosis etc.) of brain tissue. Further study of their relative contributions to the T1 app change would be helpful to understand the evolution of the ischemic lesion and its relationship with CBF change.

A similar estimation using the relationship of rCBF and ΔCBF measured during the hypercapnia (Stage 2) resulted in the CBFRC value of 1.36±0.35 ml/g/min (n = 3). This value is close to that were calculated with the data collected during the ischemic/post-ischemic stages (≈1.2 ml/g/min) although they are not exactly the same. This small discrepancy might be due to the slightly basal CBF drifting through the prolonged period of experiment because two experiments (hypercapnia and ischemia) were combined during the same MRI scanning session. It could also be related to the limited sampling size of hypercapnia experiments. Nevertheless, ΔCBF increase induced by hypercapnia calculated from ΔR1 CBF correlates well with rCBF measured by LDF.

Correlation of R1 CBF, CBF and BOLD during perturbations

Beside the aforementioned distinction of spatial responses between the ΔCBF and BOLD images owing to the different specificity to the hemodynamic response with varied vessel size, it is interesting to note that there were significantly mismatched temporal responses between measured ΔCBF and BOLD during both post-ischemia and post-hypercapnia stages. The “overshooting” effect was much less for BOLD than the ΔCBF and rCBF responses during the post-ischemia stage (Fig 3b), leading to two distinct slopes of linear regression between (rBOLD-1) and ΔR1 CBF (Fig 4b). There was also a substantial “undershooting” in the measured BOLD change during the later post-hypercapnia recovery stages (Fig 3a) compared to rCBF or rR1 CBF. One explanation for this observation is that BOLD signal reflects a complex interplay among CBF, cerebral blood volume (CBV) and oxygen consumption rate (CMRO2) [19, 20]. Therefore, BOLD can become decoupled with the CBF change, and degree of the mismatched BOLD and ΔCBF relies on the fractional changes in CBF, CBV and CMRO2 in response to a particular perturbation. The quantitative interpretation of the mismatched rCBF-rBOLD behavior requires additional measurements of CBV and CMRO2, which is beyond the scope of this article. Nevertheless, this mismatch could be linked to the uncoupling between the metabolic and hemodynamic responses associated with a physiology or pathology perturbation, and it should be useful for indirectly estimating the CMRO2 time course during the perturbation if the CBV change can be measured independently or estimated using a sophisticated BOLD modeling (e.g., [41]). In addition, the measured BOLD using the SR-T1 MRI method under fully relaxed condition reflects the “true” BOLD without the CBF confounding effect; thus, further improve the outcome of quantification [23].

A local RF coil, such as a surface coil as used in the present study, has been commonly applied for most in vivo animal MRI/MRS brain studies. Its B1 field (or profile) induces regional longitudinal magnetization changes through saturation (or inversion) preparation prior to the EPI acquisition. The combination of regional Mz preparation and relatively short artery blood traveling time from the non-saturated region into the EPI slice in animal brains is the underlying mechanism for a quantitative link between ΔCBF and ΔR1 that can be robustly imaged by the SR-T1 MRI method. Consequently, the T1 or T1-weighted MRI signal changes commonly observed in the clinical imaging diagnosis, for instance, stroke patients, are at least partially attributed by the impaired perfusion, i.e., ΔCBF. Finally, the SR-T1 MRI method can also be combined with a volume RF coil for imaging ΔCBF with the implement of a slice-selective saturation preparation.

Conclusion

In summary, we have described the SR-T1 MRI method for noninvasively and simultaneously imaging the absolute CBF change and BOLD in response to physiological/pathological perturbations. This imaging method was rigorously validated in the rat brain with simultaneous LDF measurements under global ischemia and hypercapnia conditions. It should provide a robust, quantitative MRI-based neuroimaging tool for simultaneously measuring the CBF change and BOLD contrast associated with physiological perturbations (e.g., brain activation) or pathological perturbations (e.g., stroke or pharmaceutical drug treatment).

Supporting Information

Detailed equation derivation for two-phase arterial spin model of the SR-T1 method and simulation results. Supporting information regarding the confounding effect of brain temperature change on T1 app.

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are uploaded to Figshare, as follows: R1_isch.mat DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.1320912; R1_hyper.mat DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.1320909; BOLD_isch.mat DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.1320910; BOLD_hyper.mat DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.1320911; SR_R1 PLOS ONE upload.xlsx DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.1327749.

Funding Statement

This work was partially supported by NIH grants NS057560, NS041262, NS070839, P41 RR08079 & EB015894, P30 NS057091 & NS076408 and WM Keck Foundation.

References

- 1. Detre JA, Leigh JS, Williams DS, Koretsky AP. Perfusion imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1992;23(1):37–45. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kwong KK, Belliveau JW, Chesler DA, Goldberg IE, Weisskoff RM, Poncelet BP, et al. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging of human brain activity during primary sensory stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(12):5675–9. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Williams DS, Detre JA, Leigh JS, Koretsky AP. Magnetic resonance imaging of perfusion using spin inversion of arterial water. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(1):212–6. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Edelman RR, Siewert B, Darby DG, Thangaraj V, Nobre AC, Mesulam MM, et al. Qualitative mapping of cerebral blood flow and functional localization with echo-planar MR imaging and signal targeting with alternating radio frequency. Radiology. 1994;192(2):513–20. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim SG. Quantification of relative cerebral blood flow change by flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery (FAIR) technique: application to functional mapping. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34(3):293–301. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schwarzbauer C, Morrissey SP, Haase A. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of perfusion using magnetic labeling of water proton spins within the detection slice. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35(4):540–6. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wong EC, Buxton RB, Frank LR. Implementation of quantitative perfusion imaging techniques for functional brain mapping using pulsed arterial spin labeling. NMR Biomed. 1997;10(4–5):237–49. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buxton RB, Wong EC, Frank LR. Dynamics of blood flow and oxygenation changes during brain activation: the balloon model. Magn Reson Med. 1998;39(6):855–64. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim SG, Ugurbil K. Comparison of blood oxygenation and cerebral blood flow effects in fMRI: estimation of relative oxygen consumption change. Magn Reson Med. 1997;38(1):59–65. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kwong KK, Chesler DA, Weisskoff RM, Donahue KM, Davis TL, Ostergaard L, et al. MR perfusion studies with T1-weighted echo planar imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34(6):878–87. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Calamante F, Lythgoe MF, Pell GS, Thomas DL, King MD, Busza AL, et al. Early changes in water diffusion, perfusion, T1, and T2 during focal cerebral ischemia in the rat studied at 8.5 T. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41(3):479–85. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lythgoe MF, Thomas DL, Calamante F, Pell GS, King MD, Busza AL, et al. Acute changes in MRI diffusion, perfusion, T1, and T2 in a rat model of oligemia produced by partial occlusion of the middle cerebral artery. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44(5):706–12. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van der Toorn A, Dijkhuizen RM, Tulleken CA, Nicolay K. T1 and T2 relaxation times of the major 1H-containing metabolites in rat brain after focal ischemia. NMR Biomed. 1995;8(6):245–52. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shen Q, Du F, Huang S, Duong TQ. Spatiotemporal characteristics of postischemic hyperperfusion with respect to changes in T1, T2, diffusion, angiography, and blood-brain barrier permeability. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31(10):2076–85. 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Quesson B, de Zwart JA, Moonen CT. Magnetic resonance temperature imaging for guidance of thermotherapy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;12(4):525–33. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Parker DL, Smith V, Sheldon P, Crooks LE, Fussell L. Temperature distribution measurements in two-dimensional NMR imaging. Med Phys. 1983;10(3):321–5. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dickinson RJ, Hall AS, Hind AJ, Young IR. Measurement of changes in tissue temperature using MR imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1986;10(3):468–72. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Botnar R. Interventional Magnetic Resonance Imaging, chapter 21 Temperature sensitive MR sequences. Berlin: Springer: .: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ogawa S, Lee TM, Nayak AS, Glynn P. Oxygenation-sensitive contrast in magnetic resonance image of rodent brain at high magnetic fields. Magn Reson Med. 1990;14(1):68–78. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ogawa S, Lee T-M, Kay AR, Tank DW. Brain magnetic resonance imaging with contrast dependent on blood oxygenation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9868–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mansfield P. Multi-planar image formation using NMR spin echoes. J Phys C. 1977;10:L55–L8. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ackerman JJ, Grove TH, Wong GG, Gadian DG, Radda GK. Mapping of metabolites in whole animals by 31P NMR using surface coils. Nature. 1980;283(5743):167–70. Epub 1980/01/10. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang X, Zhu XH, Zhang Y, Chen W. Large enhancement of perfusion contribution on fMRI signal. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32(5):907–18. 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tsekos NV, Zhang F, Merkle H, Nagayama M, Iadecola C, Kim SG. Quantitative measurements of cerebral blood flow in rats using the FAIR technique: correlation with previous iodoantipyrine autoradiographic studies. Magn Reson Med. 1998;39(4):564–73. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barbier EL, Silva AC, Kim SG, Koretsky AP. Perfusion imaging using dynamic arterial spin labeling (DASL). Magn Reson Med. 2001;45(6):1021–9. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang W, Williams DS, Detre JA, Koretsky AP. Measurement of brain perfusion by volume-localized NMR spectroscopy using inversion of arterial water spins: accounting for transit time and cross-relaxation. Magn Reson Med. 1992;25(2):362–71. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pulsinelli WA, Brierley JB. A new model of bilateral hemispheric ischemia in the unanesthetized rat. Stroke. 1979;10(3):267–72. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haase A, Frahm J, Matthaei D, Hanicke W, Merboldt KD. FLASH imaging. Rapid NMR imaging using low flip angle pulses. J Magn Reson. 1986;67:258–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Strupp JP. Stimulate: A GUI based fMRI analysis software package. Neuroimage 3:S607 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stern MD. In vivo evaluation of microcirculation by coherent light scattering. Nature. 1975;254(5495):56–8. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dirnagl U, Kaplan B, Jacewicz M, Pulsinelli W. Continuous measurement of cerebral cortical blood flow by laser-Doppler flowmetry in a rat stroke model. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1989;9(5):589–96. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wadhwani KC R. Blood flow in the central and peripheral nervous system In laser-Doppler blood flowmetry (öberg PA, ed).: Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic,; 1988. pp 265–88 p. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fabricius M, Lauritzen M. Laser-Doppler evaluation of rat brain microcirculation: comparison with the [14C]-iodoantipyrine method suggests discordance during cerebral blood flow increases. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16(1):156–61. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kramer MS, Vinall PE, Katolik LI, Simeone FA. Comparison of cerebral blood flow measured by laser-Doppler flowmetry and hydrogen clearance in cats after cerebral insult and hypervolemic hemodilution. Neurosurgery. 1996;38(2):355–61. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hazel RD, McCormack EJ, Miller J, Li J, Yu M, Benveniste H, et al. , editors. Measurement of Cerebrospinal Fluid Flow in the Aqueduct of a Rat Model of Hydrocephalus ISMRM Proceedings; 2006; Seattle, Washington, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kreis D, Schulz D, Stein M, Preuss M, Nestler U. Assessment of parameters influencing the blood flow velocities in cerebral arteries of the rat using ultrasonographic examination. Neurol Res. 2011;33(4):389–95. 10.1179/1743132810Y.0000000010 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Linninger AA, Xenos M, Zhu DC, Somayaji MR, Kondapalli S, Penn RD. Cerebrospinal fluid flow in the normal and hydrocephalic human brain. IEEE transactions on bio-medical engineering. 2007;54(2):291–302. 10.1109/TBME.2006.886853 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bell BA, Symon L, Branston NM. CBF and time thresholds for the formation of ischemic cerebral edema, and effect of reperfusion in baboons. J Neurosurg. 1985;62(1):31–41. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Iwama T, Yamada H, Andoh T, Sakai N, Era S, Sogami M, et al. Proton NMR studies on ischemic rat brain tissue. Magn Reson Med. 1992;25(1):78–84. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Young W, Rappaport ZH, Chalif DJ, Flamm ES. Regional brain sodium, potassium, and water changes in the rat middle cerebral artery occlusion model of ischemia. Stroke. 1987;18(4):751–9. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Davis TL, Kwong KK, Weisskoff RM, Rosen BR. Calibrated functional MRI: mapping the dynamics of oxidative metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(4):1834–9. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detailed equation derivation for two-phase arterial spin model of the SR-T1 method and simulation results. Supporting information regarding the confounding effect of brain temperature change on T1 app.

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are uploaded to Figshare, as follows: R1_isch.mat DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.1320912; R1_hyper.mat DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.1320909; BOLD_isch.mat DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.1320910; BOLD_hyper.mat DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.1320911; SR_R1 PLOS ONE upload.xlsx DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.1327749.