Abstract

Purpose

On May 14, 2013, actress Angelina Jolie disclosed that she had a BRCA1 mutation and underwent a prophylactic bilateral mastectomy. This study documents the impact of her disclosure on information-seeking behavior, specifically regarding online genetics and risk reduction resources available from the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

Methods

Using Adobe Analytics, daily page views for 11 resources were tracked from April 23, 2013 through June 25, 2013. Usage data were also obtained for four resources over a 2-year period (2012–2013). Source of referral by which viewers located a specific resource was also examined.

Results

There was a dramatic and immediate increase in traffic to NCI’s online resources. The Preventive Mastectomy fact sheet received 69,225 page views on May 14, representing a 795-fold increase compared with the previous Tuesday. A fivefold increase in page views was observed for the PDQ® Genetics of Breast and Ovarian Cancer summary in the same timeframe. A substantial increase from 0% to 49% was seen in referrals from news outlets to four resources from May 7 to May 14.

Conclusion

Celebrity disclosures can dramatically influence online information-seeking behaviors. Efforts to capitalize on these disclosures to ensure easy access to accurate information are warranted.

Keywords: hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, BRCA, information seeking, celebrity disclosure, preventive mastectomy

INTRODUCTION

On May 14, 2013, acclaimed actress and philanthropist Angelina Jolie published an op-ed in The New York Times in which she shared her decision to undergo a prophylactic bilateral mastectomy after learning that she had a deleterious BRCA1 mutation.1 Jolie’s announcement spawned a sudden and profound media response,2–6 with her face adorning the cover of both Time and People in the following weeks and much reference to the “Angelina effect.” The announcement was reported as the most blogged about medical topic in the last 5 years.7 Referrals to cancer genetics clinics increased by twofold to threefold after Jolie’s disclosure,3,8–14 with some clinics pleading for additional resources.15

Increases in information seeking have been observed following health-related disclosures by other celebrities.16–23 In the case of Jolie, an increase in information-seeking behavior is likely to be felt by the genetics community as other health professionals and the public attempt to learn more about the BRCA genes, hereditary cancers, and strategies for reducing inherited cancer risk. Conceptually, celebrity disclosures can have further downstream effects including an earlier detection of disease and reduced disease overall.24 Thus, an increased awareness of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer achieved through greater information seeking about the disease could lead to earlier identification of high-risk individuals who might benefit from intervention.

Documentation of the effect of Jolie’s disclosure on information-seeking behavior has been limited to news stories that subsequently ensued.4,25–28 To our knowledge, only one report to date has attempted to systematically measure the effect of Jolie’s announcement on information-seeking behavior.28 This report examined online information seeking surrounding two topics: mastectomy and BRCA. In the present study, we sought to systematically quantify the effect of Jolie’s disclosure on information seeking by measuring user engagement with a variety of cancer genetics and risk reduction resources available on the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) website.

NCI’s Office of Communications and Education maintains resources for both health professionals and the public. Resources for health professionals are written at a technical level that assumes an expertise in medicine. Resources for the public are written in less-technical language and often include illustrations and glossary links to explain complex terms. NCI’s Physician Data Query (PDQ®) cancer genetics information summaries for health professionals were examined in this study as were NCI’s fact sheets and Cancer Genetics Services Directory, both of which are available for the public. A list of the specific resources included in this study is presented in Table 1 with additional background on each type of resource.

Table 1.

National Cancer Institute (NCI) Resources

| Title | Resource Type | Audience |

|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer Information | ||

| BRCA1 & BRCA2: Cancer Risk and Genetic Testing | Fact sheeta | Public |

| Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy | Fact sheet | Public |

| Preventive Mastectomyb | Fact sheet | Public |

| PDQ® Genetics of Breast and Ovarian Cancer | PDQ® summaryc | Health professionals |

| Other Cancer Information | ||

| Cancer Genetics Services Directory | Directory of genetics professionalsd | Public |

| Genetic Testing for Hereditary Cancer Syndromes | Fact sheet | Public |

| PDQ® Cancer Genetics Overview | PDQ® summary | Health professionals |

| PDQ® Cancer Genetics Risk Assessment and Counseling | PDQ® summary | Health professionals |

| PDQ® Genetics of Colorectal Cancer | PDQ® summary | Health professionals |

| PDQ® Genetics of Prostate Cancer | PDQ® summary | Health professionals |

| PDQ® Genetics of Skin Cancer | PDQ® summary | Health professionals |

Fact sheets are Web documents that provide information on cancer topics in a question-and-answer format for the public. Fact sheets are developed by NCI science writers and edited and approved by NCI experts in each topic. The fact sheet collection can be accessed at the following URL: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet.

The Preventive Mastectomy fact sheet was renamed Surgery to Reduce the Risk of Breast Cancer in October 2013.

Physician Data Query (PDQ®) cancer genetics information summaries are evidence-based summaries written for health professionals about risk assessment, screening, and treatment of inherited cancer syndromes and topics related to genetic testing, genetic counseling, and psychosocial factors. The summaries are written and updated by expert members of the PDQ® Cancer Genetics Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of NCI. The PDQ® cancer genetics summaries can be accessed at the following URL: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/genetics.

The Cancer Genetics Services Directory is an online listing of individuals who provide genetic services including cancer risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic susceptibility testing. This directory is provided for the public. To be included in the directory, individuals must be licensed, board certified, or board eligible in their profession and meet other specific criteria. The Cancer Genetics Services Directory can be accessed at the following URL: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/genetics/directory.

The specific objectives of this study were to 1) identify the immediate impact of Jolie’s disclosure on Internet traffic to selected NCI cancer genetics and risk reduction resources, including fact sheets, the Cancer Genetics Services Directory, and the PDQ® cancer genetics summaries; 2) detail long-term trends of information seeking regarding these resources; and 3) determine the source by which individuals were referred to this information.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Content Identification

Table 1 provides a list of the online cancer genetics and risk reduction resources maintained by NCI’s Office of Communications and Education that were examined in this study. Resources are grouped into those specific to breast cancer and those covering other cancer genetics information.

The PDQ® genetics summaries on colorectal, prostate, and skin cancers were included in this analysis to determine whether there was an effect on Internet traffic to genetics resources for cancer types other than breast.

Data Collection

Internet traffic to these resources was measured using Adobe Analytics. Adobe Analytics is an integrated digital media analytics platform that uses page tagging to collect data; a small block of JavaScript code is added to each HTML page, which sets the values for analytic data. Each time an Internet page is accessed, the JavaScript code sends data to the Adobe Data Center, where the data are stored in repositories for reporting and analysis. Page view and referral reports were used to capture information about daily and monthly page views for these resources and sources of referral by which the resources were located.

Data Analysis

A “page view” was defined as the number of times a Web page was opened or refreshed. A “referral” from an external Web page (outside NCI’s main website) was counted if the source had a link that led readers directly to the NCI resource. For these analyses, all Internet Protocol (IP) addresses for NCI offices and NCI’s Cancer Information Service were filtered out, as were non-human “visitors” (e.g., spiders, bots).

To identify the immediate impact of Jolie’s disclosure, the magnitude of the change in page views was assessed for each resource from Tuesday, May 7, 2013 (one week before the op-ed appeared) through Tuesday, May 14, 2013 (the date it was published). Additionally, the number of page views for each resource was examined over a 9-week period (April 23, 2013 through June 25, 2013), including 3 weeks before and 6 weeks after the op-ed appeared. Daily page view data are presented for each Tuesday in this time period.

Usage data of NCI’s breast cancer resources that were collected over 2 years (January 1, 2012 through December 31, 2013) are reported to examine long-term information-seeking trends before and after Jolie’s disclosure.

To determine how individuals located the breast cancer information and understand how the source of referrals changed over time, referral data were collected for a 9-week period (April 23, 2013 through June 25, 2013). Referral sources were classified in the following categories: 1) Search engines including websites that are primarily used to identify web content that is relevant to a user’s typed entry; 2) News outlets including traditional news websites and entertainment or celebrity news websites; and 3) Other referrals including other NCI websites, typed URLs, bookmarked links, and other websites. Viewers who came to these resources from other web pages on NCI’s main website were not counted in the referral totals.

RESULTS

Immediate Impact and Short-term Trends

There was a dramatic increase in Internet traffic to NCI’s online resources on Tuesday, May 14, 2013 (see Table 2). Among breast cancer resources written for the public, the Preventive Mastectomy fact sheet saw the largest spike with 69,225 page views on May 14, representing a 795-fold increase compared with the number of page views (87) on the previous Tuesday. The BRCA1 & BRCA2: Cancer Risk and Genetic Testing fact sheet had a 31-fold increase in page views on May 14 (57,616 page views) compared with May 7 (1,787 page views). An 11-fold increase was observed for the Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy fact sheet in the same timeframe (1,229 vs. 106 page views).

Table 2.

Daily Page Views of NCI’s Cancer Information Resources, April–June 2013

| 23-Apr | 30-Apr | 7-May | 14-Maya | 21-May | 28-May | 4-Jun | 11-Jun | 18-Jun | 25-Jun | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resources for the Public | ||||||||||

| Breast Cancer Information | ||||||||||

| BRCA1 & BRCA2: Cancer Risk and Genetic Testing | 1 880 | 2 229 | 1 787 | 57 616 | 4 694 | 3 250 | 2 446 | 1 915 | 1 956 | 1 836 |

| Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy | 103 | 118 | 106 | 1 229 | 204 | 143 | 172 | 131 | 159 | 180 |

| Preventive Mastectomy | 93 | 110 | 87 | 69 225 | 1 046 | 452 | 278 | 206 | 216 | 131 |

| Other Cancer Information | ||||||||||

| Cancer Genetics Services Directory | 121 | 103 | 83 | 2 685 | 176 | 94 | 81 | 135 | 88 | 171 |

| Genetic Testing for Hereditary Cancer Syndromes | 59 | 65 | 67 | 463 | 126 | 214 | 78 | 91 | 113 | 98 |

| Resources for Health Professionals | ||||||||||

| Breast Cancer Information | ||||||||||

| PDQ® Genetics of Breast and Ovarian Cancer | 302 | 293 | 257 | 1 608 | 403 | 409 | 329 | 368 | 306 | 302 |

| Other Cancer Information | ||||||||||

| PDQ® Cancer Genetics Overview | 59 | 60 | 63 | 147 | 101 | 82 | 71 | 54 | 66 | 64 |

| PDQ® Cancer Genetics Risk Assessment and Counseling | 97 | 110 | 44 | 197 | 67 | 93 | 76 | 40 | 49 | 65 |

| PDQ® Genetics of Colorectal Cancer | 326 | 224 | 322 | 492 | 305 | 274 | 243 | 236 | 249 | 193 |

| PDQ® Genetics of Prostate Cancer | 118 | 76 | 120 | 163 | 112 | 93 | 82 | 106 | 87 | 78 |

| PDQ® Genetics of Skin Cancer | 244 | 175 | 189 | 312 | 283 | 272 | 211 | 163 | 166 | 151 |

Angelina Jolie’s op-ed, My Medical Choice, was published in The New York Times.

Several other resources for the public saw substantial increases in page views. The Cancer Genetics Services Directory had 2,685 page views on May 14, representing a 31-fold increase over the number of page views (83) on May 7, 2013. The Genetic Testing for Hereditary Cancer Syndromes fact sheet saw a sixfold increase in page views in the same timeframe (463 vs. 67 page views).

NCI’s PDQ® cancer genetics summaries for health professionals also experienced an increase in Internet traffic on the date Jolie’s op-ed appeared. A fivefold increase in page views was observed for the PDQ® Genetics of Breast and Ovarian Cancer on May 14 (1,608 page views) compared with the previous week (257 page views). Other PDQ® cancer genetics summaries not focused specifically on breast cancer also saw increases in page views on May 14 compared with the previous Tuesday. For example, the PDQ® Cancer Genetics Risk Assessment and Counseling summary had a 3.5-fold increase in page views compared with the previous week (197 vs. 44 page views). Other summaries with notable increases included the PDQ® Genetics of Skin Cancer, which saw a 65% increase in page views on May 14 compared with May 7, and the PDQ® Genetics of Colorectal Cancer, which had a 53% increase in page views in the same timeframe.

Daily traffic to these resources remained elevated over the 6 weeks following the publication of Jolie’s op-ed; it gradually returned to pre-Jolie levels toward the end of June.

Long-term Trends

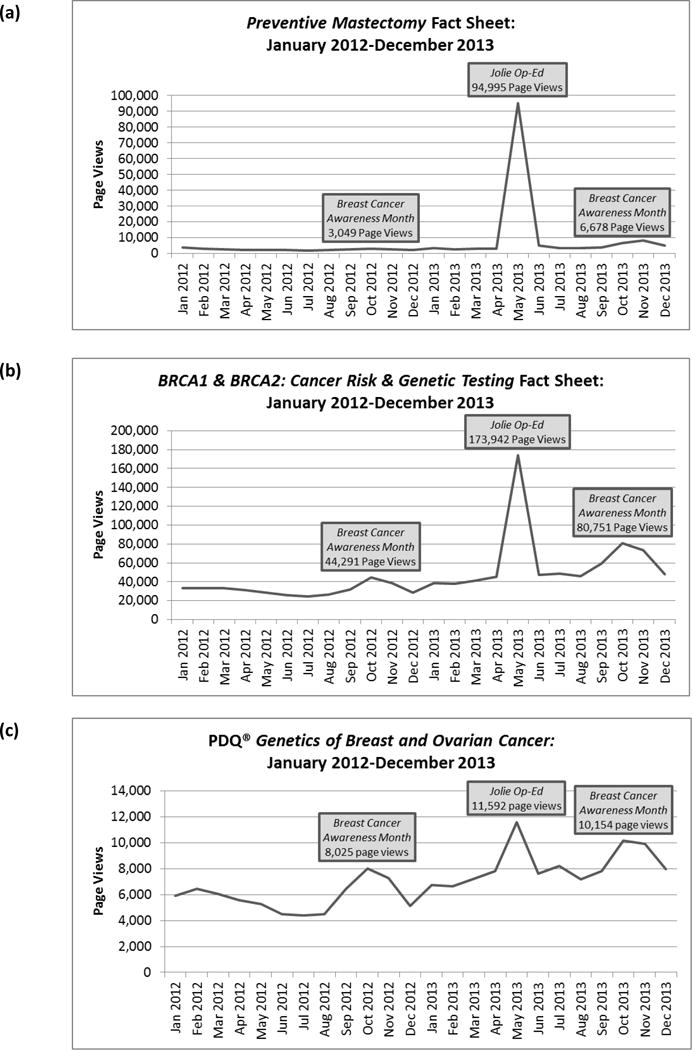

Figure 1 summarizes monthly page views for the breast cancer resources from January 2012 to December 2013. These data revealed a consistent pattern with the largest number of page views occurring in May 2013, when Jolie’s op-ed appeared. Each resource also saw an increase in page views in October 2012 and October 2013 (Breast Cancer Awareness Month in the United States), although these increases were much smaller than the peak observed in May 2013.

Figure 1.

Monthly page views of NCI’s breast cancer resources from January 2012 through December 2013, including the (a) Preventive Mastectomy fact sheet for the public; (b) BRCA1 & BRCA2: Cancer Risk and Genetic Testing fact sheet for the public; and (c) Physician Data Query (PDQ®) Genetics of Breast and Ovarian Cancer summary for health professionals. These trends reveal the magnitude of the increase in page views during May 2013, when Jolie’s op-ed was published.

The Preventive Mastectomy fact sheet (Figure 1-a) received an average of 2,667 page views each month from January 2012 through April 2013. However, the 2-year trend of monthly page views for this resource illustrates the magnitude of the increase in page views in May 2013, when Jolie’s op-ed was published (94,995 page views). The figure also illustrates a sudden post-Jolie decrease in the monthly page views in June 2013 to 5,031 page views. A comparison of the Breast Cancer Awareness Month page views in October 2012 and October 2013 shows a 1.2-fold increase in page views in October 2013 compared with October 2012 (6,678 vs. 3,049 page views).

The number of page views of NCI’s BRCA1 & BRCA2: Cancer Risk and Genetic Testing fact sheet (Figure 1-b) in May 2013 was fivefold higher than the peak seen for the previous Breast Cancer Awareness Month in October 2012. The number of page views for this fact sheet in October 2013 was 82% higher than the number of page views seen in October 2012.

Page views for the PDQ® Genetics of Breast and Ovarian Cancer (Figure 1-c) rose from an average of 6,121 monthly page views from January 2012 to April 2013 to 8,401 monthly page views from June to December 2013, reflecting a 37% increase over the longer term. Furthermore, a comparison of October 2012 to October 2013 reveals a 27% increase in page views from one year to the next.

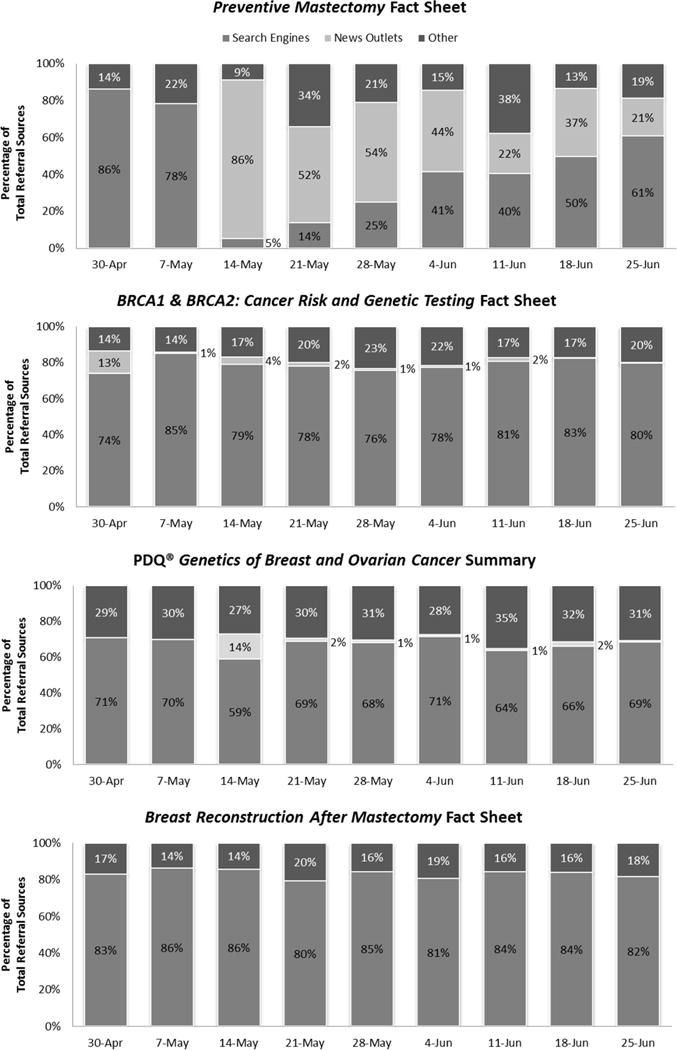

Referral Sources

In the weeks preceding Jolie’s op-ed, most viewers (approximately 80%) of NCI’s breast cancer resources examined in this study came from search engines (Table 3). On two of the three Tuesdays preceding Jolie’s op-ed, 0% of the online referrals to these resources were from news outlets via links included in news stories. However, on May 14, nearly half of all referrals (49%) to the breast cancer resources came directly from news outlets. Of these referrals, 81% were from traditional news outlets, such as The New York Times, Forbes, and CNN, whereas 6% were from celebrity news outlets, such as People and Jezebel. One week later, on May 21, 11% of the referrals were still from news outlets. In the following weeks, the proportion of referrals from news outlets waned and returned close to the level prior to Jolie’s op-ed, with only 1% of referrals attributable to news outlets on June 25, 2013.

Table 3.

| 23-Apr | 30-Apr | 7-May | 14-Mayc | 21-May | 28-May | 4-Jun | 11-Jun | 18-Jun | 25-Jun | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Search Engines | 1 751 (83%) | 1 872 (75%) | 1 691 (84%) | 49 255 (39%) | 3 874 (67%) | 2 705 (70%) | 2 157 (74%) | 1 762 (76%) | 1 877 (79%) | 1 715 (78%) |

| News Outletsd | 1(0%) | 266(11%) | 8(0%) | 61 444 (49%) | 624(11%) | 257(7%) | 138(5%) | 76(3%) | 81(3%) | 27(1%) |

| Othere | 367(17%) | 375(15%) | 319(16%) | 15 909 (13%) | 1 324 (23%) | 898(23%) | 617(21%) | 471(20%) | 433(18%) | 457(21%) |

| Total Referrals | 2 119 (100%) | 2 513 (100%) | 2 019 (100%) | 126 608 (100%) | 5 822 (100%) | 3 860 (100%) | 2 912 (100%) | 2 309 (100%) | 2 391 (100%) | 2 200 (100%) |

Referral data were captured and reported for viewers who came to NCI’s breast cancer resources from sources other than NCI’s main website, www.cancer.gov.

Preventive Mastectomy fact sheet, BRCA1 & BRCA2: Cancer Risk and Genetic Testing fact sheet, Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy fact sheet, PDQ® Genetics of Breast and Ovarian Cancer summary

Angelina Jolie’s op-ed, My Medical Choice, was published in The New York Times.

News outlets include the following: The New York Times, China Times, CNN, Forbes, PBS, US News & World Report, NPR, Chicago Tribune, Washington Post, MSN, National Geographic, Global Post, Fox, Sun-Sentinel, The Oregonian, Business insider, The Guardian, Natural Health News, Times of Israel, CBS News, USA Today, NBC News, The Guardian, Huffington Post, LA Times, Bloomberg News, People, Jezebel, Wet Paint, The Blaze, The Examiner, Boston Magazine, The Wire, and Extra.

Other referral sources include other NCI websites, typed URLs, bookmarked links, and other websites.

Figure 2 presents the proportion of referrals to each of the breast cancer resources that can be attributed to search engines, news outlets, or other websites. News outlets had the largest effect on referrals to the Preventive Mastectomy fact sheet. On April 23, April 30, and May 7, news outlets comprised 0% of the referral sources. On May 14, however, 86% of the referrals were from news outlets. News outlets remained a prominent referral source in the weeks that followed, accounting for over half of the referrals on May 21 (52%) and May 28 (54%) and 44% of the referrals on June 4. Although this proportion decreased in the following weeks, it still accounted for 21% of source referrals on June 25, 6 weeks after Jolie’s op-ed.

Figure 2.

Referral sources to NCI’s breast cancer resources from April 23, 2013 through June 25, 2013, including three fact sheets for the public (Preventive Mastectomy, BRCA1 & BRCA2: Cancer Risk and Genetic Testing, and Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy) and one summary for health professionals (Physician Data Query [PDQ®] Genetics of Breast and Ovarian). Websites of news outlets account for a large portion of the referrals to NCI’s Preventive Mastectomy fact sheet on May 14, 2013.

The BRCA1 & BRCA2: Cancer Risk & Genetic Testing fact sheet and the PDQ® Genetics of Breast and Ovarian Cancer summary each received a smaller percentage of referrals from news outlets on May 14 (4% and 14% of total daily referrals for each resource, respectively).

The Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy fact sheet received no referrals from news outlets on the 10 days studied within the 9-week time period. Search engines comprised the majority (78–86%) of referrals to this fact sheet on each of the dates studied.

DISCUSSION

The effect of Angelina Jolie’s disclosure on information-seeking behavior was dramatic and immediate, with a high impact on Internet traffic to NCI’s online resources. Our findings are consistent with previous observations of information seeking following other celebrity health-related disclosures.16–23 A study at NCI found a 400% increase in colon cancer inquiries to the Cancer Information Service after the 1985 announcement that a portion of President Ronald Reagan’s colon had been removed.22 A decade later, researchers in the United Kingdom observed a 64% increase in breast cancer-related calls to CancerBACUP, the country’s national cancer information service, following the death from breast cancer of Linda McCartney, wife of singer Paul McCartney.23 In an analysis of Internet search queries related to pancreatic cancer from 2006–2011, the diagnosis of actor Patrick Swayze and the death of Apple Computer co-founder and CEO Steve Jobs were associated with pancreatic cancer search query increases of 285% and 197%, respectively.29

In this study, we observed a profound effect on Internet traffic to NCI’s cancer genetics and risk reduction resources, most notably the Preventive Mastectomy fact sheet, after the publication of Jolie’s op-ed on May 14, 2013. This is consistent with a Google Trends analysis that identified a spike in online searches on mastectomy on May 14 and a similar increase in Internet traffic to the Wikipedia article on mastectomy.28 Online conversation about BRCA (on news websites, forums, blogs, and Twitter) also increased, though to a lesser extent, on the day Jolie’s op-ed appeared.28

Both resources written for the general public and those for health professionals experienced a spike in Internet traffic in our study. As such, Jolie’s op-ed may have had an impact on the information-seeking behaviors of health providers attempting to learn more about BRCA1 and BRCA2.30,31 Our study results support anecdotal evidence to date of increased calls to clinics by providers who had not previously referred patients for genetic counseling,12 highlighting the potential for celebrity announcements to have a significant impact on both public and provider behaviors.

Our study suggests that Jolie’s disclosure generated a spillover effect on traffic to other NCI cancer genetics resources, including those specific to other cancer sites. This suggests that the effect of a celebrity’s disclosure can be far-reaching and extend beyond the scope of the specific disease or procedure reported in the news. It is possible that people who came to the NCI website originally for information related to breast cancer or BRCA viewed other resources on the site.

Our findings reveal important insights into the timing and long-term trends of individuals seeking this online information. Specifically, page views of NCI’s breast cancer information were higher in October 2013 than in October 2012, which may reflect residual effects of Jolie’s disclosure, either through greater public awareness of the topic or continued mentions of the famous star during Breast Cancer Awareness Month.

On May 14, 86% of all referrals to the Preventive Mastectomy fact sheet were from news outlets, suggesting that readers of news articles about Jolie were highly motivated to learn more about the procedure and followed links from the articles to do so. The New York Times accounted for the majority (78%) of referrals to this fact sheet on May 14 (Jolie’s op-ed included a link to the fact sheet); however, we observed 5,546 referrals from other news outlets. There were no referrals from news outlets to this fact sheet on the previous Tuesday. Notably, 2 weeks before Jolie’s disclosure (April 30), we observed another example of a celebrity’s announcement affecting referral traffic to NCI’s breast cancer resources. Figure 2 shows 13% of referrals to the BRCA1 & BRCA2: Cancer Risk and Genetic Testing fact sheet were from news outlets on April 30. On the same day, American singer-songwriter Kara DioGuardi revealed her BRCA2 mutation status in People and her decision to have a child via a gestational surrogate. All of the referrals from news outlets on April 30 were from people.com; similar to Jolie’s editorial, the article about DioGuardi on people.com included a direct link to the fact sheet. Each of these examples illustrates the public’s readiness to seek additional information after learning of a celebrity-related health issue by following direct links from news articles.

The findings of this study have implications for genetics professionals and other health care providers who educate others about inherited disease risk and risk management. More broadly, it also has implications for organizations that aim to provide disease-specific information to the public. Jolie’s disclosure has been regarded as a “teachable moment,” with experts citing the need to communicate accurate and timely information about BRCA gene mutations, their associated cancer risks, and available preventive options in the wake of her announcement.32 Some have suggested that the media fell short of this following Jolie’s op-ed.32–34 For example, one study reported that the media failed to emphasize the rarity of Jolie’s condition.34 Another study found that awareness of Jolie’s disclosure was not associated with an improvement in understanding of breast cancer risk.33 To facilitate access to accurate and comprehensive information about inherited conditions like Jolie’s, it may be beneficial for genetics professionals to work with journalists when events such as a celebrity diagnosis draw attention to an inherited condition. Our findings suggest that news referrals to educational content are an effective means to link the public to accurate information online. As such, collaboration between journalists and genetics professionals could effectively harness the star power of a celebrity like Jolie while ensuring people obtain appropriate resources designed to educate the public about the specific condition.

In addition to collaborating with journalists, genetic professionals can use clinical encounters as an opportunity to further educate patients about credible sources of online health information that they can turn to. Our findings demonstrated a nearly immediate rise in information seeking following Jolie’s announcement; thus, organizations may wish to prepare themselves for educating the public at the time of a celebrity health episode by having an inventory of available resources to assist them in acting expeditiously to disseminate related messages and refer journalists and social media followers to appropriate information. In addition, health agencies may wish to consider innovative methods35 or multiple communication channels by which to reach their potential audience.

This is one of the first empirical studies to quantify the effect of Jolie’s disclosure on information-seeking behavior.28 Strengths of this study include the scope and reach of the resources examined and its duration, with observations focused on both the immediate and long-term impact of a celebrity disclosure. Our data reveal important trends that demonstrate not only the effect of Angelina Jolie’s disclosure on information seeking, but the influence of another celebrity and the impact of national campaigns surrounding Breast Cancer Awareness Month on Internet traffic to NCI’s breast cancer resources.

This study has several limitations. We have no knowledge of who is accessing the information, i.e., health professionals, patients, journalists, or other members of the public. We did not perform an analysis of unique visitors, thus we do not know whether the number of page views is representative of the number of individuals who viewed these resources or whether individuals accessed more than one resource. Moreover, although the increased page views during October 2013 versus October 2012 may be a result of residual attention related to Angelina Jolie, other historical trends could have contributed to the increase in Internet traffic over time. Finally, we were unable to capture referral information for individuals who used a typed or bookmarked link to access these resources, who navigated to the resources using a link from outside their Web browser (e.g., from an e-mail client), or who navigated to the resources from another NCI website. For these reasons, the “Other referrals” category in our study is broad.

Additional studies are warranted to determine whether there is a relationship between Jolie’s disclosure and cancer prevention and screening behaviors, as has been observed following other celebrity announcements.16,20–22,29 Future research might also strive to systematically quantify the increase in referrals for genetic testing and genetic counseling following Jolie’s announcement.

In sum, celebrity disclosures, such as Angelina Jolie’s revelation of her BRCA status and her prophylactic mastectomy decision, can dramatically influence online information-seeking behaviors, which may have further downstream effects on screening behaviors and disease outcomes. Genetics professionals can capitalize on these disclosures to ensure easy access to accurate information, which can help raise awareness, clarify misconceptions, and increase the likelihood of appropriate preventive actions to reduce disease risk.

Acknowledgments

This study was completed as part of the official duties of Robin Juthe at the National Cancer Institute together with Amber Zaharchuk (a contractor to the National Cancer Institute employed by iDoxSolutions, Inc.) and Catharine Wang (a member of the PDQ® Cancer Genetics Editorial Board employed by Boston University). Dr. Wang is funded by NCI K07 CA131103. We would like to thank Margaret Beckwith, Rebecca Chasan, and Richard Manrow for their thoughtful review of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Jolie A. My medical choice. The New York Times. 2013 May 14; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burstein HJ. Lou Gehrig, Angelina Jolie, and cancer genetics. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2013 Jun 1;11(6):631–632. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James PA, Mitchell G, Bogwitz M, Lindeman GJ. The Angelina Jolie effect. The Medical journal of Australia. 2013 Nov 18;199(10):646. doi: 10.5694/mja13.11218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wax E, Sun LH. Angelina Jolie’s mastectomy spotlights breast cancer, treatment options. The Washington Post. 2013 http://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/angelina-jolies-double-mastectomy-and-what-that-means-for-cancer-diagnoses/2013/05/14/0eaef124-bcb9-11e2-89c9-3be8095fe767_story.html. Accessed April 7, 2014.

- 5.Andrews H, Heil E. What Angelina Jolie’s double mastectomy means to breast cancer advocates. The Washington Post. 2013 http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/reliable-source/wp/2013/05/14/what-angelina-jolies-double-mastectomy-means-to-breast-cancer-advocates/. Accessed April 6, 2014.

- 6.Cotliar S. Angelina Jolie’s double mastectomy: what to know about the ‘faulty’ gene. People. 2013 http://www.people.com/people/article/0,,20700754,00.html. Accessed April 6, 2014.

- 7.Hurley R. Angelina Jolie’s double mastectomy and the question of who owns our genes. Bmj. 2013;346:f3340. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotz D. Increase in breast cancer gene screening: the Angelina Jolie effect. The Boston Globe. 2013 http://www.boston.com/lifestyle/health/blogs/daily-dose/2013/12/03/increase-breast-cancer-gene-screening-the-angelina-jolie-effect/2HsXjeZh6MdTE5B8T3nGMI/blog.html. Accessed April 7, 2014.

- 9.‘Angelina Jolie effect’ sparks surge in genetic testing. CBC News. 2013 http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/angelina-jolie-effect-sparks-surge-in-genetic-testing-1.2101587. Accessed April 6, 2014.

- 10.‘Angelina Effect’ sees referrals to cancer genetic clinics double. The Australian Hospital and Healthcare Bulletin. 2013 http://www.hospitalhealth.com.au/news/health/angelina-effect-sees-referrals-cancer-genetic-clinics-double/. Accessed April 7, 2014.

- 11.Lydall R. Angelina Jolie effect has doubled hospital breast cancer checks. London Evening Standard. 2013 http://www.standard.co.uk/news/health/angelina-jolie-effect-has-doubled-hospital-breast-cancer-checks-8659187.html. Accessed April 7, 2014.

- 12.Nisker J. A public health education initiative for women with a family history of breast/ovarian cancer: why did it take Angelina Jolie? Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology Canada : JOGC = Journal d’obstetrique et gynecologie du Canada : JOGC. 2013 Aug;35(8):689–694. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30856-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Leary C. Jolie effect clogs cancer services. The West Australian. 2013 http://au.news.yahoo.com/a/18026217/jolie-effect-clogs-cancer-services/. Accessed April 7, 2014.

- 14.Stokes K. Angelina effect having huge impact on SA women as genetic testing referrals for breast cancer triple. Herald Sun. 2013 http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/national/angelina-effect-having-huge-impact-on-sa-women-as-genetic-testing-referrals-for-breast-cancer-triple/story-fnii5yv7-1226729551932. Accessed April 7, 2014.

- 15.McPherson L. Angelina Jolie effect: Doctors plead for extra funding as they prepare for surge in genetic testing requests. Daily Record. 2013 http://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/news/health/angelina-jolie-effect-doctors-plead-1896942. Accessed April 7, 2014.

- 16.Chapman S, McLeod K, Wakefield M, Holding S. Impact of news of celebrity illness on breast cancer screening: Kylie Minogue’s breast cancer diagnosis. The Medical journal of Australia. 2005 Sep 5;183(5):247–250. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb07029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casey GM, Morris B, Burnell M, Parberry A, Singh N, Rosenthal AN. Celebrities and screening: a measurable impact on high-grade cervical neoplasia diagnosis from the ‘Jade Goody effect’ in the UK. British journal of cancer. 2013 Sep 3;109(5):1192–1197. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ayers JW, Althouse BM, Noar SM, Cohen JE. Do celebrity cancer diagnoses promote primary cancer prevention? Preventive medicine. 2014 Jan;58:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Metcalfe D, Price C, Powell J. Media coverage and public reaction to a celebrity cancer diagnosis. Journal of public health. 2011 Mar;33(1):80–85. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith DP, Clements MS, Wakefield MA, Chapman S. Impact of Australian celebrity diagnoses on prostate cancer screening. The Medical journal of Australia. 2009 Nov 16;191(10):574–575. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb03320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lancucki L, Sasieni P, Patnick J, Day TJ, Vessey MP. The impact of Jade Goody’s diagnosis and death on the NHS Cervical Screening Programme. Journal of medical screening. 2012;19(2):89–93. doi: 10.1258/jms.2012.012028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown ML, Potosky AL. The presidential effect: the public health response to media coverage about Ronald Reagan’s colon cancer episode. Public opinion quarterly. 1990 Fall;54(3):317–329. doi: 10.1086/269209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boudioni M, Mossman J, Jones AL, Leydon G, McPherson K. Celebrity’s death from cancer resulted in increased calls to CancerBACUP. Bmj. 1998 Oct 10;317(7164):1016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7164.1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noar SM, Willoughby JF, Myrick JG, Brown J. Public figure announcements about cancer and opportunities for cancer communication: a review and research agenda. Health communication. 2014;29(5):445–461. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2013.764781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haglage A. I’m 25 and I have the Angie gene. The Daily Beast. 2013 http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/05/15/i-m-25-and-i-have-the-angie-gene.html. Accessed April 6, 2014.

- 26.Kluger J, Park A. The Angelina effect. Time. 2013;181:28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee J. Celebrity impact: benefits, risks seen in hype over Jolie’s disclosure. Modern Healthcare. 2013:10–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reid B. The ‘Angelina Effect’ in four charts. Huffington Post. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noar SM, Ribisl KM, Althouse BM, Willoughby JF, Ayers JW. Using digital surveillance to examine the impact of public figure pancreatic cancer announcements on media and search query outcomes. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Monographs. 2013 Dec;2013(47):188–194. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgt017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bellcross CA, Leadbetter S, Alford SH, Peipins LA. Prevalence and healthcare actions of women in a large health system with a family history meeting the 2005 USPSTF recommendation for BRCA genetic counseling referral. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2013 Apr;22(4):728–735. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mouchawar J, Klein CE, Mullineaux L. Colorado family physicians’ knowledge of hereditary breast cancer and related practice. Journal of cancer education : the official journal of the American Association for Cancer Education. 2001 Spring;16(1):33–37. doi: 10.1080/08858190109528721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmidt C. Honing the health message on BRCA mutations. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2013 Dec 18;105(24):1843–1844. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borzekowski DL, Guan Y, Smith KC, Erby LH, Roter DL. The Angelina effect: immediate reach, grasp, and impact of going public. Genet Med. 2013 Dec 19; doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamenova K, Reshef A, Caulfield T. Angelina Jolie’s faulty gene: newspaper coverage of a celebrity’s preventive bilateral mastectomy in Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom. Genet Med. 2013 Dec 19; doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooper CP, Gelb CA, Vaughn AN, Smuland J, Hughes AG, Hawkins NA. Directing the public to evidence-based online content. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 2014 Jul 22; doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]